Fuzhou

Fuzhou, alternately romanized as Foochow, is the capital and one of the largest cities in Fujian province, China.[4] Along with the many counties of Ningde, those of Fuzhou are considered to constitute the Mindong (lit. Eastern Fujian) linguistic and cultural area.

Fuzhou 福州市 Hokciu | |

|---|---|

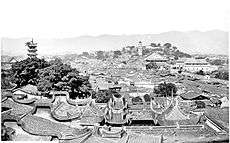

From top, left to right: Black Pagoda of Fuzhou, Xichan Temple Pagoda of Fuzhou; Xichan Temple, City Skyline of Fuzhou; Gulou District of Fuzhou | |

| |

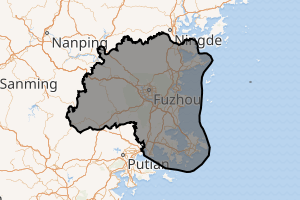

.svg.png) Location of Fuzhou City jurisdiction in Fujian | |

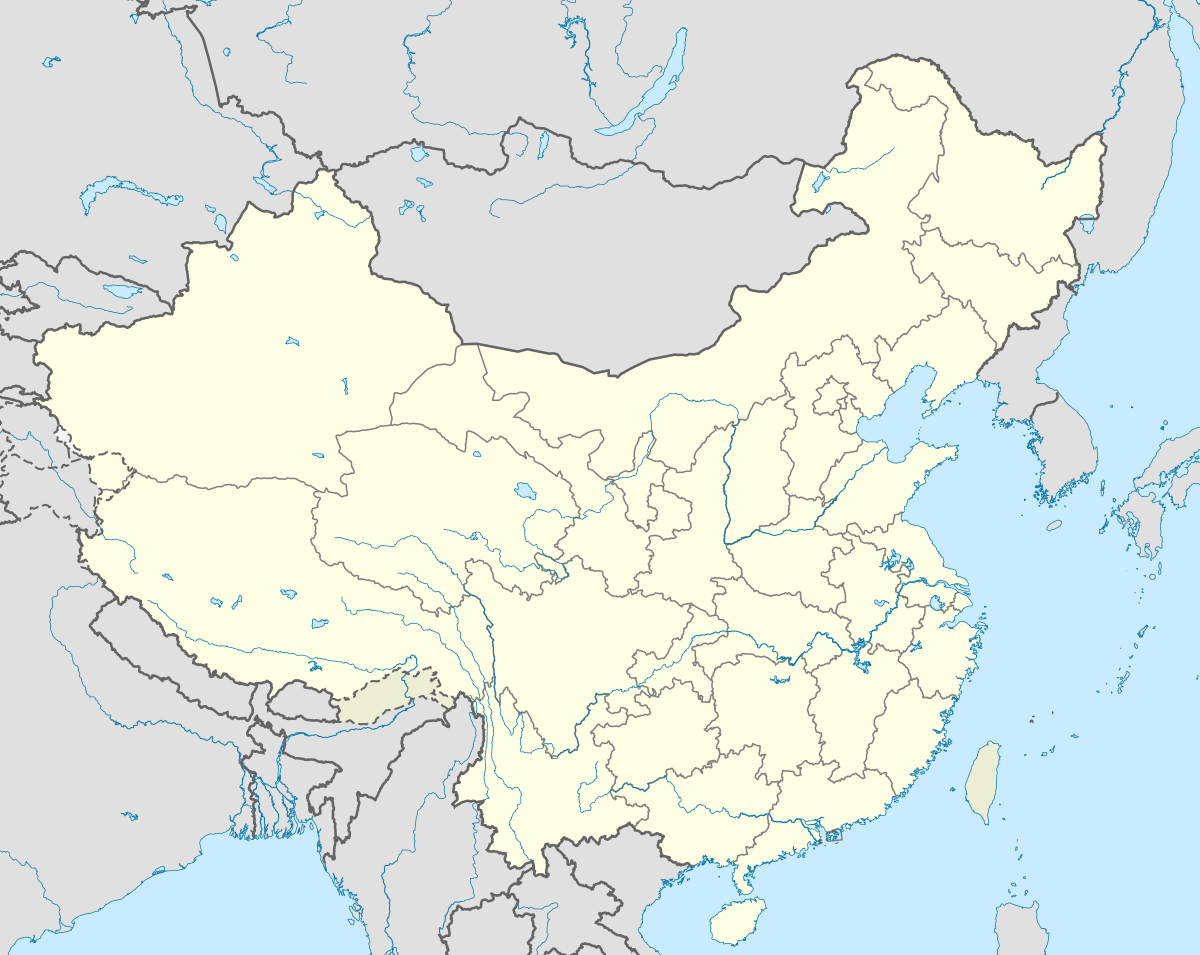

Fuzhou Location in China | |

| Coordinates (Fuzhou municipal government): 26°04′27″N 119°17′47″E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | Fujian |

| Municipal seat | Gulou District |

| Divisions - County-level | 6 districts, 6 counties, & 1 County-level cities(2017) |

| Government | |

| • CPC Ctte Secretary | Wang Ning (王宁) |

| • Mayor | You Mengjun (尤猛军) |

| Area | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 12,177 km2 (4,702 sq mi) |

| • Water | 4,634 km2 (1,790 sq mi) |

| • Urban (2018)[1] | 1,243 km2 (480 sq mi) |

| Population (2017)[2] | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 7,660,000 |

| • Urban (2018)[3] | 5,400,000 |

| • Rural | 2,707,294 |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 350000 |

| Area code(s) | 591 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-FJ-01 |

| GDP | 2018[2] |

| - Total | CNY 785.681 billion US$118.683 billion |

| - Per capita | CNY 102,569 US$15,494 |

| - Growth | |

| License plate prefixes | 闽A |

| Local dialect | Fuzhou dialect of the Eastern Min Language |

| Website | Fuzhou.gov.cn |

| Fuzhou | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Fuzhou" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 福州 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Foochow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Blessed Prefecture" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fuzhou lies on the north (left) bank of the estuary of Fujian's largest river, the Min River. All along its northern border lies Ningde, and Ningde's Gutian County lies upriver. Its population was 7,115,370 inhabitants as of the 2010 census, of whom 4,408,076 inhabitants are urban representing around 61.95%, while rural population is at 2,707,294 representing around 38.05%.[2] In 2015, Fuzhou was ranked as the 10th fastest growing metropolitan area in the world by Brookings Institution.[5] Fuzhou is listed as No. 20 in China Integrated City Index 2016's total ranking, a study conducted by National Development and Reform Commission.[6]

Names

Fuzhou in Chinese is "有福之州" (yǒufúzhīzhōu), meaning "a city with good luck." The Yuanhe Maps and Records of Prefectures and Counties, a Chinese geographical treatise published in the 9th century, says that Fuzhou's name came from Mount Futo, a mountain northwest of the city. The mountain's name was then combined with -zhou, meaning "settlement" or "prefecture," in a manner similar to many other Chinese cities. During the Warring States period, area of Fuzhou was sometimes referred to as Ye (Chinese: 冶), and Fuzhou was incorporated into China proper during Qin dynasty. The city's name was changed numerous times between the 3rd and 9th centuries before finally settling on Fuzhou in 948.[7] In Chinese, the city is sometimes referred to by the poetic nickname Rongcheng (Chinese: 榕城; Foochow Romanized: Ṳ̀ng-siàng), lit.: 'The Banyan City'.

In older English publications, the name is variously romanized as Foochow, Foo-Chow,[8] Fuchow, Fūtsu, Fuh-Chow, Hock Chew, and Hokchew.

History

Pre-Qin history (before 221 BC)

The remains of two Neolithic cultures—the Huqiutou Culture (虎丘頭文化), from around 5000 BC, and the Tanshi Mountain Culture (曇石山文化), from around 3000 BC—have been discovered and excavated in the Fuzhou area. During the Warring States period (c. 475–221 BC), Chinese began referring to the modern Fujian area as Min Yue (閩越), suggesting that the native inhabitants of the area were a branch of the Yue peoples, a diverse population of non-Chinese tribes who once inhabited most of southern China.[9] In 306 BC, the Yue Kingdom (present-day Zhejiang) fell to the state of Chu. Han Dynasty historian Sima Qian wrote that the surviving members of the Yue royal family fled south to what is now Fujian, where they settled alongside the native Yue people, joining Chinese and Yue culture to create Minyue.[10] Their major centre was not at Fuzhou's modern location, but further up the Min watershed near Wuyishan City.

Qin and Han dynasties (221 BC–AD 206)

The First Emperor of Qin unified ancient China in 221 BC and desired to bring the southern and southeast regions under Chinese rule. The Qin dynasty organized its territory into "Commanderies" (Chinese: 郡; pinyin: jùn)—roughly equivalent to a province or prefecture—and the Fujian area was organized as Minzhong Commandery (閩中郡). The area seems to have continued mostly independent of Chinese control for the next century. The Han dynasty followed the short-lived Qin, and Emperor Gaozu of Han declared both Minyue and neighboring Nanyue to be autonomous vassal kingdoms. In 202 BC, Emperor Gaozu enfeoffed a leader named Wuzhu (無諸; Old Chinese: Matya) as King of Minyue, and a walled city called Ye (冶; Old Chinese: Lya; literally: Beautiful) was built. The founding of Ye in 202 BC has become the traditional founding date of the city of Fuzhou.

In 110 BC, the armies of Emperor Wu of Han defeated the Minyue kingdom's armies during the Han–Minyue War and annexed its territory and people into China.[11] Many Minyue citizens were forcibly relocated into the Jianghuai area, and the Yue ethnic group was mostly assimilated into the Chinese, causing a sharp decline in Ye's inhabitants.[9] The area was eventually re-organized as a county in 85 BC.

Three Kingdoms to Sui dynasty (200–618)

During the Three Kingdoms Period, southeast China was nominally under the control of Eastern Wu, and the Fuzhou area had a shipyard for the coastal and Yangtze River fleets. In 282, during the Jin dynasty, two artificial lakes known simply as the East Lake and West Lake were constructed in Ye, as well as a canal system. The core of modern Fuzhou grew around these three water systems, though the East and West Lakes no longer exist. In 308, during the War of the Eight Princes at the end of the Jin dynasty, the first large-scale migration of Chinese immigrants moved to the south and southeast of China began, followed by subsequent waves during later periods of warfare or natural disaster in the Chinese heartland. The administrative and economic center of the Fujian area began to shift to the Ye area during the Sui dynasty (581–618).

Tang to the ten kingdoms era (618–960)

In 725, the city was formally renamed "Fuzhou". Throughout the mid-Tang dynasty, Fuzhou's economic and cultural institutions grew and developed. The later years of the Tang saw a number of political upheavals in the Chinese heartland such as the An Lushan Rebellion and Huang Chao Rebellion, prompting another wave of northerners to immigrate to the modern-day Northern Min and Eastern Min areas. In 879, a large part of the city was captured by the army of Huang Chao during their rebellion against the Tang government. In 893, the warlord brothers Wang Chao and Wang Shenzhi captured Fuzhou in a rebellion against the Tang dynasty, successfully gaining control of the entire Fujian Province and eventually proclaiming their founding of an independent kingdom they called the Min Kingdom in 909. The Wang brothers enticed more immigrants from the north, though their kingdom only survived until 945. In 978, Fuzhou was incorporated into the newly founded Song dynasty, though their control of the mountainous regions was tenuous.

Fuzhou prospered during the Tang dynasty. Buddhism was quickly adopted by the citizens who quickly built many Buddhist temples in the area.

Song era (960–1279)

Fuzhou underwent a major dramatic surge in its refined culture and educational institutions throughout the Song Dynasty as Fuzhou produced 10 Fuzhounese zhuangyuan scholars (scholar who is ranked the top first place in the imperial examinations zh:状元), a large number for a small city in the country during that dynasty.

The Hualin Temple (華林寺, not to be confused with the temple of the same name in Guangzhou), founded in 964, is one of the oldest surviving wooden structures in China. New city walls were built in 282, 901, 905, and 974, so the city had many layers of walls – more so than the Chinese capital. Emperor Taizong of the Song dynasty ordered the destruction of all the walls in Fuzhou in 978 but new walls were rebuilt later. The latest was built in 1371. During the Southern Song dynasty, Fuzhou became more prosperous; many scholars came to live and work. Among them were Zhu Xi, the most celebrated Chinese philosopher after Confucius, and Xin Qiji, the greatest composer of the ci form of poetry.

Marco Polo, an Italian guest of the Emperor Kubilai, transcribed, after the conventions of Italian orthography, the place name as Fugiu. This was not the local Min pronunciation but that of the mandarin administrative class.

According to Odoric of Pordenone, Fuzhou had the biggest chickens in the world.[12]

Ming dynasty (1368–1644)

Between 1405 and 1433, a fleet of the Ming Imperial navy under Admiral Zheng He sailed from Fuzhou to the Indian Ocean seven times; on three occasions the fleet landed on the east coast of Africa. Before the last sailing, Zheng erected a stele dedicated to the goddess Tian-Fei (Matsu) near the seaport.

The Ming government gave a monopoly over Philippine trade to Fuzhou, which at times was shared with Quanzhou.[13]

Galeote Pereira, a Portuguese soldier and trader, was taken prisoner during the pirate extermination campaign of 1549 and imprisoned in Fuzhou. Later transferred to a form of internal exile elsewhere in the province, Pereira escaped to Langbaijiao in 1553. The record of his experiences in the Ming Empire, logged by the Jesuits at Goa in 1561, was the first non-clerical account of China to reach the West since Marco Polo.[14]

The Ryukyu Kingdom established an embassy in Fuzhou.

Qing dynasty (1644-1912)

In 1839, Lin Zexu, who himself was a Fuzhou native, was appointed by the Daoguang Emperor to enforce the imperial ban on the opium trade in Canton. His unsuccessful actions, however, precipitated the disastrous First Opium War with Great Britain, and Lin, who had become a scapegoat for China's failure in war, was exiled to the northwestern section of the empire. The Treaty of Nanjing (1842), which put an end to the conflict, made Fuzhou (then known to Westerners as Foochow) one of five Chinese treaty ports, and it became completely open to Western merchants and missionaries.[15][16]

Fuzhou was one of the most important Protestant mission fields in China. On January 2, 1846, the first Protestant missionary, Rev. Stephen Johnson (missionary) from ABCFM, entered the city and soon set up the first missionary station there. ABCFM was followed by the Methodist Episcopal Missionary Society that was led by Revs. M. C. White and J. D. Collins, who reached Fuzhou in early September 1847. The Church Missionary Society also arrived in the city in May 1850. These three Protestant agencies remained in Fuzhou until the communist revolution in China in the 1950s, leaving a rich heritage in Fuzhou's Protestant culture. They supported the creation of hospitals and schools, including the Woolston Memorial Hospital, run by the American-trained Hü King Eng.[17]

On August 23, 1884, the Battle of Fuzhou broke out between the French Far East Fleet and the Fujian Fleet of the Qing dynasty. As the result, the Fujian Fleet, one of the four Chinese regional fleets, was destroyed completely in Mawei Harbor.

Republic of China

On November 8, 1911, revolutionaries staged an uprising in Fuzhou. After an overnight street battle, the Qing army surrendered.

Revolutionary Republic

On November 22, 1933, Eugene Chen and the leaders of the National Revolutionary Army's 19th Army set up the short-lived People's Revolutionary Government of Republican China.[18] Blockaded by Chiang Kai-shek and left without support from the nearby Soviet Republic of China, the PRGRC collapsed within two months.[19]

Japanese occupation

With the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, hostilities commenced in Fujian Province. Xiamen (Amoy) fell to a Japanese landing force on May 13, 1938. The fall of Amoy instantly threatened the security of Fuzhou. On May 23, Japanese ships bombarded Mei-Hua, Huang-chi and Pei-Chiao while Japanese planes continued to harass the Chinese forces. Between May 31 and June 1, Chinese gunboats Fu-Ning, Chen-Ning and Suming defending the blockade line in the estuary of the Min River were successively bombed and sunk. Meanwhile, the Chinese ship Chu-Tai berthed at Nan-Tai was damaged. The Chinese Navy's Harbor Command School, barracks, shipyard, hospital and marine barracks at Ma-Wei were successively bombed.[20] Fuzhou is recorded as having fallen to Japanese forces in 1938.[21]

The extent of Japanese command and control of the city of Fuzhou itself as opposed to the port at Mawei and the Min River Estuary is uncertain. By 1941 (date unknown), the city is recorded as having returned to Nationalist control. The British Consulate in Fuzhou is noted as operational from 1941–1944 after the United Kingdom Declaration of War on Japan in December 1941. Western visitors to Fuzhou in the period 1941–1944 include the Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett in 1942.[22] and the British scientist Dr Joseph Needham in May 1944.[23] Both visitors record the presence of a British Consul and a Fuzhou Club comprising western businessmen.

In The Man Who Loved China: The Fantastic Story of the Eccentric Scientist Who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom, author Simon Winchester relates the visit of Dr Needham in 1944. Needham encountered the American government agent (John Caldwell) and the British SIS agent (Murray MacLehose working undercover as the British Vice-Consul in Fuzhou) involved in aid to the Nationalist resistance to Japanese forces in Fujian Province.[23]

As part of Operation Ichi-Go (1944), the last large-scale Japanese offensive in China in World War 2, the Japanese intended to isolate Fuzhou and the Fujian Province corridor to Nationalist forces in western China and the wartime capital of Chongqing. One account of the Japanese re-taking of Fuzhou city itself is narrated by American naval officer, Houghton Freeman.[24] The date is given as October 5, 1944.[25]

Fuzhou remained under Japanese control until the surrender of Japan and its armed forces in China in September 1945.

Following the restitution of Republic control (1946), the administration divisions of Fuzhou were annexed, and administration level was promoted from county-level to city-level officially.

People's Republic of China

Fuzhou was occupied by People's Liberation Army with little resistance on 17 August 1949.[26]

In the 1950s, the city was on the front line of the conflict with KMT in Taiwan, as hostile KMT aircraft frequently bombed the city. The bombing on 20 January 1955 was the most serious one, killing hundreds of people.[27]

Fuzhou was also involved in violent mass chaos during the Cultural revolution. Different groups of Red Guards fought with each other using guns on the streets of the city, and even attacking the People's Liberation Army.[28]

Under the reform and opening policy since the late 1970s, Fuzhou has developed rapidly. In 1982, Fuzhou became the first city in China where the stored program control was introduced, which marked a milestone in the history of telecommunications in China.[29] In 1984, Fuzhou was chosen as one of the first branches of Open Coastal Cities by the Central Government.[30]

On December 13, 1993, a raging fire swept through a textile factory in Fuzhou and claimed the lives of 60 workers.[31]

On October 2, 2005, floodwaters from Typhoon Longwang swept away a military school, killing at least 80 paramilitary officers.[31]

Geography

Fuzhou is located in the northeast coast of Fujian province, connects jointly northwards with Ningde and Nanping, southwards with Quanzhou and Putian, westwards with Sanming respectively.

Climate

Fuzhou has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) influenced by the East Asian Monsoon; the summers are long, very hot and humid, and the winters are short, mild and dry. In most years, torrential rain occurs during the monsoon in the second half of May. Fuzhou is also liable to typhoons in late summer and early autumn. The monthly 24-hour average temperature ranges from 10.9 °C (51.6 °F) in January to 28.9 °C (84.0 °F) in July, while the annual mean is 19.84 °C (67.7 °F). With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 24 percent in March to 54 percent in July, the city receives 1,607 hours of bright sunshine annually. Extremes since 1951 have ranged from −1.9 °C (29 °F) on 25 January 2016 to 41.7 °C (107 °F) on 26 July 2003.[32][33] Snow is very rare, having covered the ground last times in February 1957, December 1975 and December 1991.

| Climate data for Fuzhou (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.6 (74.5) |

28.5 (83.3) |

30.3 (86.5) |

36.2 (97.2) |

37.5 (99.5) |

39.1 (102.4) |

41.7 (107.1) |

40.6 (105.1) |

39.3 (102.7) |

36.7 (98.1) |

33.4 (92.1) |

26.5 (79.7) |

41.7 (107.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

19.2 (66.6) |

23.9 (75.0) |

27.7 (81.9) |

30.9 (87.6) |

34.5 (94.1) |

33.7 (92.7) |

31.0 (87.8) |

27.0 (80.6) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.1 (64.6) |

25.1 (77.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.4 (52.5) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.3 (57.7) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

29.3 (84.7) |

28.8 (83.8) |

26.6 (79.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

20.5 (68.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) |

9.3 (48.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

19.8 (67.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.6 (78.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

19.7 (67.5) |

15.5 (59.9) |

10.9 (51.6) |

17.4 (63.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −1.9 (28.6) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

0.3 (32.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

20.3 (68.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

4.6 (40.3) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 49.9 (1.96) |

84.9 (3.34) |

141.5 (5.57) |

154.4 (6.08) |

187.8 (7.39) |

202.0 (7.95) |

123.0 (4.84) |

169.4 (6.67) |

156.4 (6.16) |

47.6 (1.87) |

40.9 (1.61) |

34.0 (1.34) |

1,391.8 (54.78) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 9.7 | 14.4 | 17.5 | 17.8 | 18.2 | 15.9 | 10.4 | 12.1 | 11.6 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 149.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 75 | 77 | 76 | 76 | 79 | 74 | 75 | 72 | 67 | 68 | 70 | 73 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 101.6 | 79.2 | 89.1 | 111.0 | 114.4 | 141.9 | 225.6 | 199.2 | 153.7 | 144.2 | 120.3 | 126.9 | 1,607.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 31 | 25 | 24 | 29 | 28 | 35 | 54 | 49 | 42 | 40 | 37 | 39 | 36 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration (precipitation days, sunshine data 1971–2000),[34][35] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2000[2] | 6,386,013 | — |

| 2010[2] | 7,115,370 | +11.4% |

| Population size may be affected by changes on administrative divisions. | ||

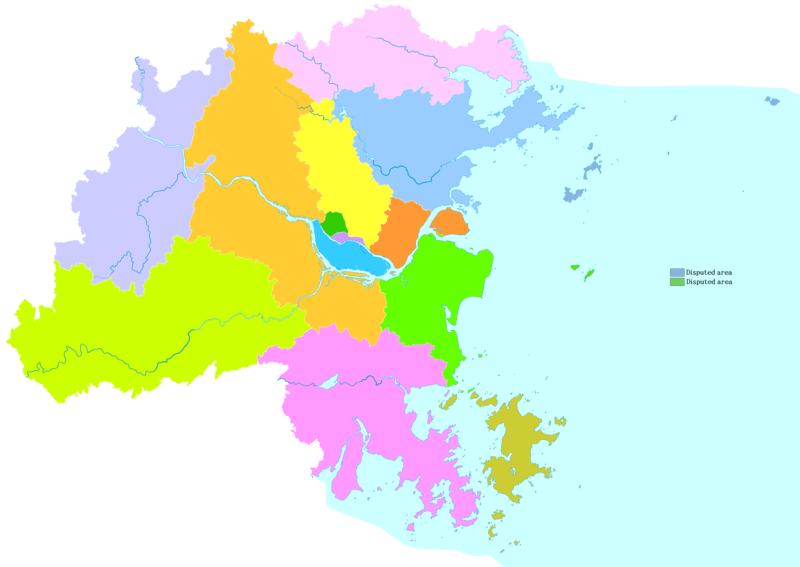

The administrative divisions of Fuzhou have been changed frequently throughout history. From 1983, the Fuzhou current administrative divisions were formed officially, namely, 5 districts and 8 counties. In 1990 and 1994, Fuqing (Foochow Romanized: Hók-chiăng) and Changle (Foochow Romanized: Diòng-lŏ̤h) counties were promoted to county-level cities; Changle became a district in 2017. Despite these changes, the administrative image of "5 districts and 8 counties" is still held popularly among local residents. Fuzhou's entire area only covers 9.65 percent of Fujian Province.

The city of Fuzhou has direct jurisdiction over 6 districts, 1 county-level city, and 6 counties:

| Map | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Name | Chinese (S) | Hanyu Pinyin | Foochow Romanized | Population (2010 census)[2] |

Area (km²) | Density (/km²) |

| City proper | 2,921,763 | 1,015.07 | 2878.39 | |||

| Gulou District | 鼓楼区 | Gǔlóu Qū | Gū-làu-kṳ̆ | 687,706 | 36.60 | 18,790 |

| Taijiang District | 台江区 | Táijiāng Qū | Dài-gĕ̤ng-kṳ̆ | 446,891 | 18.28 | 24,447 |

| Cangshan District | 仓山区 | Cāngshān Qū | Chŏng-săng-kṳ̆ | 762,746 | 139.41 | 5,471 |

| Mawei District | 马尾区 | Mǎwěi Qū | Mā-muōi-kṳ̆ | 231,929 | 254.33 | 912 |

| Jin'an District | 晋安区 | Jìn'ān Qū | Céng-ăng-kṳ̆ | 792,491 | 566.45 | 1,399 |

| Changle District | 长乐区 | Chánglè Qū | Diòng-lŏ̤h-kṳ̆ | 682,626 | 717.54 | 951 |

| Suburban and Rural | ||||||

| Minhou County | 闽侯县 | Mǐnhòu Xiàn[36] | Mìng-âu-gâing | 662,118 | 2,133.03 | 310 |

| Lianjiang County | 连江县 | Liánjiāng Xiàn | Lièng-gŏng-gâing | 561,490 | 1,190.67 | 472 |

| Luoyuan County | 罗源县 | Luóyuán Xiàn | Lò̤-nguòng-gâing | 207,677 | 1,081.17 | 192 |

| Minqing County | 闽清县 | Mǐnqīng Xiàn | Mìng-chiăng-gâing | 237,643 | 1,468.90 | 162 |

| Yongtai County | 永泰县 | Yǒngtài Xiàn | Īng-tái-gâing | 249,455 | 2,243.41 | 111 |

| Pingtan County | 平潭县 | Píngtán Xiàn | Bìng-tàng-gâing | 357,760 | 371.09 | 964 |

| Satellite cities | ||||||

| Fuqing | 福清市 | Fúqīng Shì | Hók-chiăng-chê | 1,234,838 | 1,932.43 | 639 |

| Total | 7,115,370 | 12,153.31 | 585.47 | |||

Culture

The City of Banyans is distinct from the mainstream inland cultures of central China, and in details vary from other areas of the Chinese coast

Language and art

Besides Mandarin Chinese, the majority local residents of Fuzhou (Fuzhou people) also speak Fuzhou dialect (福州話), the prestige form of Eastern Min.

Min opera, also known as Fuzhou drama, is one of the major operas in Fujian Province. It enjoys popularity in the Fuzhou area and in neighboring parts of Fujian such as the northeast and northwest areas where the Fuzhou dialect is spoken, as well as in Taiwan and the Malay Archipelago. It became a fixed opera in the early 20th century. There are more than 1,000 plays of Min opera, most of which originate from folk tales, historical novels, or ancient legends, including such traditional plays as "Making Seal", "The Purple Jade Hairpin" and "Switching Fairy Peach with Litchi".[37]

Architecture

Religion

The two traditional mainstream religions practiced in Fuzhou are Mahayana Buddhism and Taoism. Traditionally, many people practice both religions simultaneously. The city is also home to many Buddhist monasteries, Taoist temples and Buddhist monks.

Apart from mainstream religions, a number of religious worship sites of various local religions are situated in the streets and lanes of Fuzhou.

The origins of local religion can be dated back centuries. These diverse religions incorporated elements such as gods and doctrines from other religions and cultures, such as totem worship and traditional legends. For example, Monkey King, originated to monkey worship among local ancients, gradually came to embody the God of Wealth in Fuzhou after the novel Journey to the West was issued in Ming dynasty.

As the most popular religion in the Min River Valley, the worship of Lady Linshui is viewed as one of the three most influential local religions in Fujian, the other two being the worship of Mazu and Baosheng Dadi (保生大帝).

Local cuisine

Fuzhou cuisine is most notably one of the four traditional cooking styles of Fujian cuisine, which in turn is one of the eight Chinese regional cuisines. Dishes are light but flavorful, with particular emphasis on umami taste, known in Chinese cooking as xianwei (simplified Chinese: 鲜味; traditional Chinese: 鮮味; pinyin: xiānwèi), as well as retaining the original flavor of the main ingredients instead of masking them. In Fuzhou cuisine, the taste is light compared to that of some other Chinese cooking styles, and often have a mixed sweet and sour taste. Soup, served as an indispensable dish in meals, is cooked in various ways with local seasonal fresh vegetables and seafood and often added with local cooking wine (福建老酒).

Fuzhou is famous for its street food and snacks. Some notable street food dishes include Fuzhou fish balls (魚丸), meat-pastry dumplings (扁肉燕), rice scroll soup (鼎邊糊), gong pian (光餅; a kind of mildly savoury pastry), and pork floss (肉鬆). Many of these street food dishes have a long history; for example, rice scroll soup became popular in Fuzhou in the early part of the Qing dynasty. As more Fuzhou residents settled overseas, Fuzhou dishes spread to Taiwan, Southeast Asia and the U.S.. For example, one is able to find gong pian and Fuzhou fish balls in Sitiawan in Ipoh, Malaysia while Fuzhou fish balls, meat-pastry dumplings and rice scroll soup can be found in New York's Chinatown.

Fuzhou residents also enjoy eating festival foods during traditional Chinese holidays. For example, red and white rice cakes (年糕) are served over Chinese New Year, stuffed yuanxiao (元宵) during the Lantern Festival, zongzi (粽子) during the Dragon Boat Festival, and sweet soy bean powder-covered plain yuanxiao over the winter solstice.

Special crafts

Bodiless lacquerware (脫胎漆器), paper umbrellas and horn combs (角梳) are the "Three Treasures" of Fuzhou traditional arts. In addition, bodiless lacquerware, together with cork pictures (軟木畫) and Shoushan stone sculptures (壽山石雕) are called "Three Superexcellences" of Fuzhou.

Media

Fuzhou Evening News (福州晚报), Strait News (海峡都市报) and Southeast Express (东南快报) are the three most primary newspapers in the city. Fuzhou Daily (福州日报) is the official newspaper of the Fuzhou Committee of Communist Party of China.[38] FZTV, the local municipal television station has four channels.[39] As the capital, the provincial state-owned Fujian Media Group, Fujian Daily Newspaper Group and Straits Publishing & Distributing Group also headquarter here.

Transportation

Airports

The city is served by Fuzhou Changle International Airport, which replaces Fuzhou Yixu Airport, the old airfield. The former is its main international airport and an air-hub in southeast China, while the latter was turned into a PLA airbase after 1997.

Railways

Fuzhou is a railway hub in northern Fujian. The Wenzhou–Fuzhou and Fuzhou–Xiamen Railways form part of the Southeast Coast High-Speed Rail Corridor and can accommodate high-speed trains at speeds of up to 250 km/h (155 mph). The Hefei–Fuzhou High-Speed Railway links the city to Beijing through its nearby inner land province Jiangxi at speeds up to 350 km/h (220 mph). The Nanping–Fuzhou Railway and Xiangtang–Putian Railway provide rail access inland. The latter line can carry trains at speeds of 200 km/h (124 mph). The regional Fuzhou-Mawei Cargo Railway runs from the Fuzhou Railway Station eastward to the port in Mawei District. Fuzhou has two main railway stations, Fuzhou and Fuzhou South. Fuzhou station is often just referred to as Fuzhou station given its central location.

Metro

Fuzhou Metro is the first rapid transit system in Fujian province, has two metro lines in operation, the first line opened linking the south of the city and the north above the Min River, and five lines under construction.[40]

_01.jpg)

Line 1 links the two railway stations of the city. The Fuzhou Railway Station is located north of the city center, near the North Second Ring Road. Fuzhou South Railway Station, located in Cangshan district, is a key landmark of the New City development scheme, begun in 2007 and completed in 2010. Line 1 was opened on May 18, 2016.

Line 2 runs in the east–west direction of the city, linking the university city and Fuzhou High-Tech Zone in Minhou county, Jinshan Industrial Zone in Cangshan district, and Gushan mountain in Jin'an district. Line 2 was opened on 26 April 2019.

Seaport

Passenger liners regularly sail between ROC's Matsu Islands and the port in Mawei District.[41][42]

A high-speed ferry sails across Taiwan Strait between the port in Pingtan County, the mainland's closest point to Taiwan, to Taipei and Taichung, a trip that takes about 3 hours.[43]

History of Fuzhou port

In 1867 the Fuzhou seaport was the site of one of China's first major experiments with Western technology, when the Fuzhou Navy Yard was established. A shipyard and an arsenal were built under French guidance and a naval school was opened. A naval academy was also established at the shipyard, and it became a center for the study of European languages and technical sciences. The academy, which offered courses in English, French, engineering, and navigation, produced a generation of Western-trained officers, including the famous scholar-reformer Yan Fu (1854–1921).

The yard was established as part of a program to strengthen China in the wake of the country's disastrous defeat in the Second Opium War (1856–60). Most talented students nonetheless continued to pursue a traditional Confucian education, and by the mid-1870s the government began to lose interest in the shipyard, which had trouble securing funds and declined in importance. Fuzhou remained essentially a commercial center and a port until World War II; it had relatively little industry. The port was occupied by the Japanese during 1940–45.

Since 1949, Fuzhou has grown considerably. Transportation has been improved by the dredging of the Min River for navigation by medium-sized craft upstream to Nanping. In 1956 the railway linking Fuzhou with the interior of the province and with the main Chinese railway system began operation. The port has also been improved; Fuzhou itself is no longer accessible to seagoing ships, but Luoxingta anchorage and the outer harbor at Guantou on the coast of the East China Sea have been modernized and improved. The chief exports are timber, fruits, paper, and foodstuffs.

Economy

| Year | GDP (billions of CN¥) |

Growth (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 172.000 | 9.8 |

| 2006 | 165.694 | 12.2 |

| 2007 | 197.459 | 15.1 |

| 2008 | 228.416 | 13.0 |

| 2009 | 252.428 | 12.8 |

| 2010 | 306.821 | 14.0 |

| 2011 | 373.478 | 13.0 |

Industry is supplied with power by a grid running from the Gutian hydroelectric scheme in the mountains to the northwest. The city is a center for commercial banking, designer brands and timber-working, engineering, papermaking, printing, and textile industries. A small iron and steel plant was built in 1958. In 1984 Fuzhou was designated one of China's "open" cities in the new open-door policy inviting foreign investments. Handicrafts remain important in the rural areas, and the city is famous for its lacquer and wood products.

Its GDP was ¥75,614 (c. US$12,140) per capita in 2015, ranked no. 52 among 659 Chinese cities.

Fuzhou is undoubtedly the province's political, economic and cultural center as well as an industrial center and seaport on the Min River. In 2008, Fuzhou's GDP amounted to ¥228.4 billion, an increase of 13 percent.[44]

Manufactured products include chemicals, silk and cotton textiles, iron and steel, and processed food. Among Fuzhou's exports are fine lacquerware and handcrafted fans and umbrellas. The city's trade is mainly with Chinese coastal ports. Its exports of timber, food products, and paper move through the harbor at Guantou located about 50 kilometres (31 mi) downstream.[45]

In 2008, exports reached US$13.6 billion, a growth of 10.4 percent while imports amounted to US$6.8 billion. Total retail sales for the same period came to ¥113.4 billion and per capita GDP grew to ¥33,615.[45] During the same period, Fuzhou approved 155 foreign-invested projects. Contracted foreign investment amounted to US$1.489 billion, while utilized foreign investment increased by 43 percent to US$1.002 billion.[45]

.jpg)

Economic and Technological Zones

- Fuzhou Economic & Technological Development Zone

The Fuzhou Economic & Technological Development Zone was established in January 1985 by State Council, with a total planning area of 22 square kilometres (8.5 sq mi) and now has 10.1 square kilometres (3.9 sq mi) built. It is located close to Fuzhou Changle International Airport and Fuzhou Port. Industries encouraged in the zone include electronics assembly & manufacturing, telecommunications equipment, trading and distribution, automobile production/assembly, medical equipment and supplies, shipping/warehousing/logistics and heavy industry.[46]

- Fuzhou Export Processing Zone

The Fuzhou Export Processing Zone was founded on June 3, 2005, with the approval of the State Council and enjoys all the preferential policies. It is located inside the Chang'an Investment Zone of the Fuzhou Economic and Technical Development Zone (FETDZ) with a planned land area of 1.14 square kilometres (0.44 sq mi).[47]

- Fuzhou Free Trade Zone

The Fuzhou Free Trade Zone was established in 1992 by the State Council, with a planning area of 1.8 square kilometres (0.69 sq mi). Industries encouraged in the free trade zone include electronics assembly & manufacturing, heavy industry, instruments & industrial equipment production, shipping/warehousing/logistics, telecommunications equipment, trading, and distribution.[48]

- Fuzhou Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone

Residential Buildings in Fuzhou

Residential Buildings in Fuzhou

The Fuzhou High-tech Development Zone was set up in 1988 and approved by the State Council in March 1991. In 1995, the Fuzhou Municipal Government decided to build Baiyi Electronic Information City, which covers 1.2 square kilometres (0.46 sq mi) in the zone, making it the lead electronic industrial zone in Fuzhou. The Administrative Commission of Mawei High-tech Park was set up in the zone in 1999. It covers an area of 5.6 square kilometres (2.2 sq mi), and is in the area between Gushan Channel and Mawei Channel, Jiangbin Road and Fuma Road.[49]

- Fuzhou Science and Technology Park

The Fuzhou Science and Technology Park was established in 1988 and was approved to be a national-level zone by the State Council in 1991. The planned area is 5.5 square kilometres (2.1 sq mi) and is divided into 3 parts: the Mawei portion, the Cangshan portion, and the Hongshan portion. The main industries are electronics, information technology, and biotechnology. The zone is 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) away from the China National Highway 316 and 41 kilometres (25 mi) away from the Fuzhou Changle International Airport.[50]

- Fuzhou Taiwan Merchant Investment Area

The Fuzhou Taiwan Merchants Development Zone was approved to be established in May 1989 by the State Council. The zone is located in the Fuzhou Economic and Technological Development Zone. The zone is a commercial base for Taiwan-related development. The current area is 6 square kilometres (2.3 sq mi). The main industries are IT, metallurgy, food processing, and textiles. The zone is 11.5 kilometres (7.1 mi) away from the 316 National Highway and 52 kilometres (32 mi) away from Fuzhou Changle International Airport.[51]

Cityscape

Tourist attractions

Historical / cultural

Sanfang Qixiang (三坊七巷) "Three Lanes and Seven Alleys" is a cluster of ancient residential buildings dating from the late Jin dynasty now features a pedestrian zone with shops along the street. Situated at the centre of the city at Gulou District, it is the most popular touristic destination in the city. Many buildings were revitalized recently to increase tourism.

- Lin Zexu Memorial Hall (林则徐纪念馆) (Aomen Rd)

- West Lake (福州西湖) (An artificial landscape-style lake built in 282)

- Hualin Temple (华林寺) (Built in 964, Song dynasty) Its main hall is known as the oldest surviving wooden building in south China and was confirmed as an important heritage site under state protection in 1982.

- Dizang Temple (The Temple of Sacrificing Guardian of the Earth, founded in 527)

- Xichan Temple (西禅寺) (Founded in 867)

- Wu Ta (乌塔) "Black Pagoda" (Originally built in 799, rebuilt in 936)

- Bai Ta (白塔) "White Pagoda" (On the top of Mount Yu, originally built in 905, 67 m in height, collapsed in 1534, rebuilt in 1548, 41 m in height)

- Yongquan Temple (涌泉寺) (Founded in 915, and located on the top of Mount Gu)

- Mount Gu (鼓山), the tallest mountain in the area. Attracts many residents, especially in the weekends for hiking trips.

- Mount Qi (旗山) (In Nanyu, Minhou County.)

- Luoxing Tower (罗星塔) (In Mawei District and built in the Song dynasty. Was called "China Tower")

- Tanshishan cultural relics (昙石山文化遗址) (In Ganzhe, Minhou County)

- Saint Dominic's Cathedral

- St. John's Church, Fuzhou

- Fuzhou Confucian temple

Saint Dominic's Cathedral

Saint Dominic's Cathedral St. John's Church, Fuzhou

St. John's Church, Fuzhou

Recreational

- Fujian Museum (福建省博物院) (Near West Lake)

- Wulongjiang Shidi Park (乌龙江湿地公园) (A wetland park. However, the park is in distress due to ineffective environmental protection and construction)

- Beach Park (沙滩公园)Chating Park (茶亭公园)

Fuzhou Beach Park

Fuzhou Beach Park - Zuohai Park (左海公园)

- Minjiang Park (闽江公园) (On the two banks of the Min River)

- Pingshan Park (屏山公园)

- Mount Jinniu Park (金牛山公园) (Near the Fuzhou West Long-Distance Bus Station)

- Mount Jinji Park (金鸡山公园)

- Fuzhou National Forest Park (福州国家森林公园)

- Sandiejing Forest Park (三叠井森林公园)

- Fuzhou Hot Spring Park (福州温泉公园)

- Fuzhou Zoo (福州动物园) (This new zoo was built in 2008 after moving from its old location by West Lake)

Notable people

- Sa Zhenbing (萨镇冰, 1859–1952), high-ranking naval officer of Mongolian origin

- Go Seigen (吳清源, 1914–2014), Weiqi/Go player, considered by many players to be the greatest player of the game in the 20th century and one of the greatest of all time

- Lin Changmin (zh:林長民, 1876–1925), a high-rank governor in the Beiyang Government

- Lin Huiyin (林徽因, 1904–1955), architect and writer

- Lin Juemin (林觉民, 1887–1911), one of 72 Revolutionary Martyrs at Huanghuagang, Guangzhou

- Murong Shenxing (慕容慎行, 1934–2018), neuroscientist, researcher and doctor

- Ingen (隱元隆琦, 1592–1673), well known Buddhist monk, poet and calligrapher who lived during Ming Dynasty

- Zheng Xiaoxu (鄭孝胥, 1860–1938), statesman, diplomat and calligrapher

- Chih-Tang Sah (薩支唐, 1932–), Chinese-American engineer of Mongolian origin

- Chen Shaokuan (陳紹寬, 1889–1969), Fleet Admiral who served as the senior commander of naval forces of the National Revolutionary Army

- Bing Xin (冰心, 1900–1999), writer

- Zhan Shi Chai (詹世釵, 1840s–1893), entertainer as "Chang the Chinese giant"

- Wong Nai Siong (黄乃裳, 1849–1924), Christian scholar, and founding father of Malaysian town of Sibu, in the state of Sarawak

- Lin Shu (林纾, 1852–1924), scholar and translator, most famous for his translation of Alexandre Dumas' La Dame aux Camélias

- Yan Fu (严复, 1854–1921), scholar and translator, best known for introducing western ideas such as Darwinian evolution

- Lin Sen (林森, 1868–1943), President of the Republic of China from 1931 to 1943

- Liu Buchan (劉步蟾, 1852-1895), naval officer of the Beiyang Fleet, the most prominent of China's naval units in the late Qing Dynasty

- Lin Zexu (林则徐, 1785–1850), scholar and official, considered a national hero for his strong opposition to the trade of opium before the First Anglo-Chinese War

- Hsien Wu (吳憲, 1893–1959), protein scientist

- Yao Jinnan (姚金男, 1995–present) Chinese artistic gymnast who represented China at the London 2012 Olympic Games. She is the 2014 World Uneven Bars Champion and a 5 time world medallist at the 2011 World Gymnastics Championships and the 2014 World Gymnastics Championships.

- Shen Baozhen (沈葆桢, 1820–1879), Viceroy of Liangjiang from 1875 to 1879

- Chen Baochen (陈宝琛, 1848–1935), scholar and loyalist to the Qing dynasty

- Hou Debang (侯德榜, 1890–1974), chemical engineer

- Lin Xiangqian (zh:林详谦, 1892–1923), a martyr, labor movement leader and an early member of the Communist Party of China (CPC)

- Lu Yin (zh:廬隱, 1898–1934), writer

- Fan Tchunpi, painter and ceramicist

- Zheng Zhenduo (郑振铎, 1898–1958), journalist and literary scholar

- Watchman Nee (倪柝声, 1903–1972), Christian author and church leader

- Chen Jingrun (陈景润, 1933–1996), mathematician who made significant contributions to number theory

- Chen Zhangliang (陈章良, 1962–), biologist, elected as vice-governor of Guangxi in 2007

- Shen-su Sun (孫賢鉥, 27 Oct 1943 – 5 Mar 2005), geochemist

- E.A. Coffin, (10 Mar 1888 - 20 Jan 1972), rear admiral in the United States coast guard

Education

Colleges and universities

- Fujian Normal University (福建师范大学; founded in 1907)

- Fuzhou University (福州大学; founded in 1958)

- Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (福建农林大学; founded in 1958)

Three Universities above take the leading position in the province, and they are supported by Fujian Government to build High-level University.[52][53]

- Fujian Medical University

- Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine

- Minjiang University

- Fujian University of Technology

- Fujian Police College

- Fujian Commercial College

Note: Institutions without full-time bachelor programs are not listed.

High schools

- Fuzhou No.8 Middle School (福州第八中学)

- Fuzhou Foreign Language School (福州外国语学校)

- Fuzhou Gezhi High School (福州格致中学)

- Fuzhou No.1 Middle School (福建省福州第一中学)

- Fuzhou No.3 Middle School (福州第三中学)

- Fuzhou Senior High School (福州高级中学)

- Fuzhou No.4 Middle School (福州第四中学)

- Fuzhou No.2 Middle School (福州第二中学)

- The Affiliated High School Of Fujian Normal University (福建师范大学附属中学)

- Fuzhou Pingdong Middle School (福州屏东中学)

See also

- Nantai Island

- List of cities in the People's Republic of China by population

- List of twin towns and sister cities in China

References

- Cox, W (2018). Demographia World Urban Areas. 14th Annual Edition (PDF). St. Louis: Demographia. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-05-03. Retrieved 2018-08-06.

- "Fuzhou Municipal Statistic Bureau". Fuzhou.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- Cox, W (2018). Demographia World Urban Areas. 14th Annual Edition (PDF). St. Louis: Demographia. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-05-03. Retrieved 2018-08-06.

- "Illuminating China's Provinces, Municipalities and Autonomous Regions". PRC Central Government Official Website. Archived from the original on 2013-12-10. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- Jesus Leal Trujillo, Joseph Parilla (February 10, 2015). "The World's 10 Fastest Growing Metropolitan Areas". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- 2016中国城市综合发展指标发布 北上深位列三甲. Archived from the original on 2017-03-25. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- Zhongguo Gujin Diming Dacidian (中国古今地名大词典), (Shanghai: Shanghai Cishu Chubanshe, 2005), 3116.

- Sladen, Douglas (1895), "Bits of China", The Japs at Home, 5th ed., New York: New Amsterdam Book Co., p. 279.

- Xu Xiaowang (徐曉望 (2006). 福建通史. Fujian People's Press (福建人民出版社).

- Records of the Grand Historian, Yue Wang Goujian Shijia 越王勾踐世家.

- Yu 1986, p. 456.

- Yule 2002, p. 124.

- Jacques Gernet (1996). A history of Chinese civilization (2, illustrated, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 420. ISBN 0-521-49781-7. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

Foochow was reserved for trade with the Philippines (a similar role had been assumed by Ch'iian- chou between 1368 and 1374 and again after 1403 in the Yung-le era)

- Spence, Jonathan D., The Chan's Great Continent: China in Western Minds, 1999, W.W.Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-31989-7, pp.20–21

- "Treaty of Nanjing 1842 (original text)". US-China Institute. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Treaty of Nanjing (original document)" (PDF). Columbia.edu. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

-

- Burton, Margaret E. (1912). Notable Women of Modern China. New York: Fleming H. Revell. p. 42. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16. Retrieved 2017-03-15.

- 中華共和國人民革命政府; Zhōnghuá Gònghéguó Rénmín Gémìng Zhèngfǔ, also known as the Fujian People's Revolutionary Government (福建人民革命政府, Fújiàn Rénmín Zhèngfǔ). Compare 中華共和國 to the shorter, more ambiguous 中華民國 (Zhonghua Minguo, "Folk-state of China"), which was the one-party state under Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-shek against which Chen and the 19th rebelled (translated into English nonetheless as the "Republic of China").

- 晚清民國史 [History of the late Qing and the Republic]. 五南圖書出版股份有限公司. 2002. pp. 440–. ISBN 978-957-11-2898-6. Archived from the original on 2014-09-25. Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- Hu, Pu-yu (1974). A brief history of Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) (1st ed.). Taipei, Taiwan: Chung Wu Publishing Co. p. 142.

- Dreyer, Edward L. (1995). China at War, 1901–1949. London, New York City: Longman. p. 107. ISBN 0-521480-01-9.

- Strahan, Lachlan (1996). Australia's China: Changing Perceptions from the 1930s to the 1990s. Cambridge, New York City: Cambridge University Press. p. 235. ISBN 0-582051-25-8.

- Winchester, Simon. (2008). The Man Who Loved China: The Fantastic Story of the Eccentric Scientist Who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom (1st ed.). New York: Harper. pp. 143–151. ISBN 978-0060884598.

- Smith, Nancy. "The Freeman Orientation". Wesleyan Alumni Magazine. Wesleyan University. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010.

- "League of Nations Timeline – 1944". Indiana University. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- 福州有福,完好无损迎来解放. society.people.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2012-06-11. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- 一·二○”大轰炸60周年 沙县退休职工忆尘封历史. 66163.com. 2015-02-04. Archived from the original on 2017-11-16. Retrieved 2017-05-05.

- 军队介入平息福州武斗乱局. Archived from the original on 2017-10-18.

- 福州万门程控电话开通25周年纪念专题.

- OPENING TO THE OUTSIDE WORLD Archived 2017-04-26 at the Wayback Machine. China.org.cn

- Major Events Across The Taiwan Straits Archived April 28, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-03-18. Retrieved 2014-11-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Extreme Temperatures Around the World". Archived from the original on 2013-06-25. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- 中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年) (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data. China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 2017-09-23. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- 现代汉语词典(第七版 [A Dictionary of Current Chinese (Seventh Edition)]. Beijing: The Commercial Press. 1 September 2016. p. 547. ISBN 978-7-100-12450-8.

闽侯(Mǐnhòu),地名,在福建。

- "Min Opera". cultural-china.com. Archived from the original on 2012-05-25.

- 福州的报纸. Archived from the original on 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- 福州广播电视台本台介绍. Archived from the original on 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- "Fuzhou Metro merges sleek future with rich heritage". www.chinadaily.com.cn. 10 January 2017. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- Direct shipping services between Taiwan's Matsu and Mawei in mainland China Archived 2017-03-30 at the Wayback Machine, China Daily, 2010-04-19

- 福州连江县黄岐至马祖白沙客运航线通航. Xinhua News Fujian. Archived from the original on 2017-03-25. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- "First high-speed ship to Taiwan sails out of Pingtan". Archived from the original on 2017-03-25. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- "China Expat city Guide Dalian". China Expat. 2008. Archived from the original on 2009-02-17. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- "China Briefing Business Reports". Asia Briefing. 2009. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- "Fuzhou Economic & Technological Development Zone". RightSite.asia. Archived from the original on 2012-04-18. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- "Fuzhou Export Processing Zone". RightSite.asia. 2005-06-03. Archived from the original on 2012-04-18. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- "Fuzhou Free Trade Zone". RightSite.asia. Archived from the original on 2012-04-18. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- "Fuzhou Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone". RightSite.asia. Archived from the original on 2012-04-18. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- "Fuzhou Science and Technology Park". RightSite.asia. Archived from the original on 2012-04-18. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- "Fuzhou Taiwan Merchants Development Zone". RightSite.asia. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- 'High-level university construction' a hot phrase at Fujian two sessions Archived 2017-03-30 at the Wayback Machine, China Daily, 2016-01-19

- 福州大学、福建师范大学、福建农林大学着手建设高水平大学. Fujian Daily. 2014-02-20. Archived from the original on 2017-03-30 – via 163.com.

Sources

- A Brief History of The Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), Hu Pu-yu, (Chung Wu Publishing Co. Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China, 1974) pg 142.

- China at War 1901–1949, Edward L. Dreyer, (Longman, London and New York, 1995) pg 235.

- Australia's China, Changing Perceptions from the 1930s to the 1990s, Lachlan Strachan, (Cambridge University Press 1996) pg 107.

- Bomb, Book & Compass, Joseph Needham and the Great Secrets of China, Simon Winchester, (Penguin *Group Australia, Camberwell, Victoria) pp 143–151.

- op.cit.

- Yule, Henry (2002), The Travels of Friar Odoric

- wesleyan.edu

- indiana.edu

- politics.people.com.cn

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Fuzhou Government website(in Chinese)

- Introduction to Fuzhou and local news on China Daily website (in English)

- Fuzhou Places to visit.

- Fuzhou News Net(in Chinese)

- Fuzhou Municipal Television Station(in Chinese)

- An early history of Fujian and Fuzhou (in Chinese)

- Maritime Art - On the River Min(in English)

- Fuzhou Daily, Fuzhou Evening News and its Overseas Edition, the local newspapers(in Chinese)

- Historic US Army map of Fuzhou, 1945