Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS FRGS FLS FZS[2] (/ˈdɑːrwɪn/;[5] 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist and biologist,[6] best known for his contributions to the science of evolution.[I] His proposition that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestors is now widely accepted, and considered a foundational concept in science.[7] In a joint publication with Alfred Russel Wallace, he introduced his scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection, in which the struggle for existence has a similar effect to the artificial selection involved in selective breeding.[8] Darwin has been described as one of the most influential figures in human history,[9] and he was honoured by burial in Westminster Abbey.[10]

Charles Darwin FRS FRGS FLS FZS | |

|---|---|

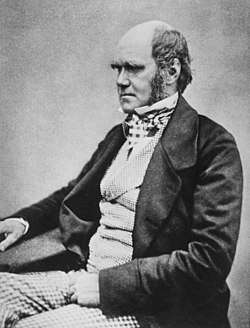

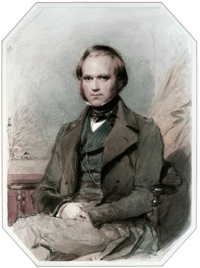

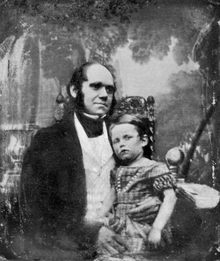

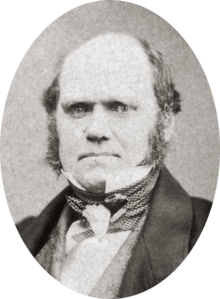

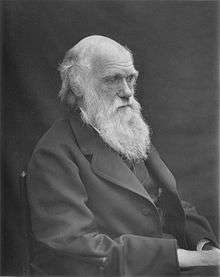

Darwin, c. 1854, when he was preparing On the Origin of Species for publication[1] | |

| Born | Charles Robert Darwin 12 February 1809 |

| Died | 19 April 1882 (aged 73) |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Known for | |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 10 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Natural history, geology |

| Institutions | Tertiary education:

Professional institution: |

| Academic advisors | |

| Influences |

|

| Influenced | Hooker, Huxley, Romanes, Haeckel, Lubbock |

| Signature | |

| |

Darwin published his theory of evolution with compelling evidence in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species.[11][12] By the 1870s, the scientific community and a majority of the educated public had accepted evolution as a fact. However, many favoured competing explanations which gave only a minor role to natural selection, and it was not until the emergence of the modern evolutionary synthesis from the 1930s to the 1950s that a broad consensus developed in which natural selection was the basic mechanism of evolution.[13][14] Darwin's scientific discovery is the unifying theory of the life sciences, explaining the diversity of life.[15][16]

Darwin's early interest in nature led him to neglect his medical education at the University of Edinburgh; instead, he helped to investigate marine invertebrates. Studies at the University of Cambridge (Christ's College) encouraged his passion for natural science.[17] His five-year voyage on HMS Beagle established him as an eminent geologist whose observations and theories supported Charles Lyell's conception of gradual geological change, and publication of his journal of the voyage made him famous as a popular author.[18]

Puzzled by the geographical distribution of wildlife and fossils he collected on the voyage, Darwin began detailed investigations, and in 1838 conceived his theory of natural selection.[19] Although he discussed his ideas with several naturalists, he needed time for extensive research and his geological work had priority.[20] He was writing up his theory in 1858 when Alfred Russel Wallace sent him an essay that described the same idea, prompting immediate joint publication of both of their theories.[21] Darwin's work established evolutionary descent with modification as the dominant scientific explanation of diversification in nature.[13] In 1871 he examined human evolution and sexual selection in The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, followed by The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872). His research on plants was published in a series of books, and in his final book, The Formation of Vegetable Mould, through the Actions of Worms (1881), he examined earthworms and their effect on soil.[22][23]

Biography

Early life and education

Charles Robert Darwin was born in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, on 12 February 1809, at his family's home, The Mount.[24][25] He was the fifth of six children of wealthy society doctor and financier Robert Darwin and Susannah Darwin (née Wedgwood). His grandfathers Erasmus Darwin and Josiah Wedgwood were both prominent abolitionists. Erasmus Darwin had promoted theories of evolution and common descent in his Zoonomia (1794), anticipating his grandson's work.[26]

Both families were largely Unitarian, though the Wedgwoods were adopting Anglicanism. Robert Darwin, himself quietly a freethinker, had baby Charles baptised in November 1809 in the Anglican St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury, but Charles and his siblings attended the Unitarian chapel with their mother. The eight-year-old Charles already had a taste for natural history and collecting when he joined the day school run by its preacher in 1817. That July, his mother died. From September 1818, he joined his older brother Erasmus attending the nearby Anglican Shrewsbury School as a boarder.[27]

Darwin spent the summer of 1825 as an apprentice doctor, helping his father treat the poor of Shropshire, before going to the University of Edinburgh Medical School (at the time the best medical school in the UK) with his brother Erasmus in October 1825. Darwin found lectures dull and surgery distressing, so he neglected his studies. He learned taxidermy in around 40 daily hour-long sessions from John Edmonstone, a freed black slave who had accompanied Charles Waterton in the South American rainforest.[28]

In Darwin's second year at the university he joined the Plinian Society, a student natural-history group featuring lively debates in which radical democratic students with materialistic views challenged orthodox religious concepts of science.[29] He assisted Robert Edmond Grant's investigations of the anatomy and life cycle of marine invertebrates in the Firth of Forth, and on 27 March 1827 presented at the Plinian his own discovery that black spores found in oyster shells were the eggs of a skate leech. One day, Grant praised Lamarck's evolutionary ideas. Darwin was astonished by Grant's audacity, but had recently read similar ideas in his grandfather Erasmus' journals.[30] Darwin was rather bored by Robert Jameson's natural-history course, which covered geology—including the debate between Neptunism and Plutonism. He learned the classification of plants, and assisted with work on the collections of the University Museum, one of the largest museums in Europe at the time.[31]

Darwin's neglect of medical studies annoyed his father, who shrewdly sent him to Christ's College, Cambridge, to study for a Bachelor of Arts degree as the first step towards becoming an Anglican country parson. As Darwin was unqualified for the Tripos, he joined the ordinary degree course in January 1828.[32] He preferred riding and shooting to studying. During the first few months of Darwin's enrollment, his second cousin William Darwin Fox was also studying at Christ's Church. Fox impressed him with his butterfly collection, introducing Darwin to entomology and influencing him to pursue beetle collecting.[33][34] He did this zealously, and had some of his finds published in James Francis Stephens' Illustrations of British entomology (1829–32).[34][35] Also through Fox, Darwin became a close friend and follower of botany professor John Stevens Henslow.[33] He met other leading parson-naturalists who saw scientific work as religious natural theology, becoming known to these dons as "the man who walks with Henslow". When his own exams drew near, Darwin applied himself to his studies and was delighted by the language and logic of William Paley's Evidences of Christianity[36] (1794). In his final examination in January 1831 Darwin did well, coming tenth out of 178 candidates for the ordinary degree.[37]

Darwin had to stay at Cambridge until June 1831. He studied Paley's Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity (first published in 1802), which made an argument for divine design in nature, explaining adaptation as God acting through laws of nature.[38] He read John Herschel's new book, Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy (1831), which described the highest aim of natural philosophy as understanding such laws through inductive reasoning based on observation, and Alexander von Humboldt's Personal Narrative of scientific travels in 1799–1804. Inspired with "a burning zeal" to contribute, Darwin planned to visit Tenerife with some classmates after graduation to study natural history in the tropics. In preparation, he joined Adam Sedgwick's geology course, then on 4 August travelled with him to spend a fortnight mapping strata in Wales.[39][40]

Survey voyage on HMS Beagle

After leaving Sedgwick in Wales, Darwin spent a week with student friends at Barmouth, then returned home on 29 August to find a letter from Henslow proposing him as a suitable (if unfinished) naturalist for a self-funded supernumerary place on HMS Beagle with captain Robert FitzRoy, emphasising that this was a position for a gentleman rather than "a mere collector". The ship was to leave in four weeks on an expedition to chart the coastline of South America.[41] Robert Darwin objected to his son's planned two-year voyage, regarding it as a waste of time, but was persuaded by his brother-in-law, Josiah Wedgwood II, to agree to (and fund) his son's participation.[42] Darwin took care to remain in a private capacity to retain control over his collection, intending it for a major scientific institution.[43]

After delays, the voyage began on 27 December 1831; it lasted almost five years. As FitzRoy had intended, Darwin spent most of that time on land investigating geology and making natural history collections, while HMS Beagle surveyed and charted coasts.[13][44] He kept careful notes of his observations and theoretical speculations, and at intervals during the voyage his specimens were sent to Cambridge together with letters including a copy of his journal for his family.[45] He had some expertise in geology, beetle collecting and dissecting marine invertebrates, but in all other areas was a novice and ably collected specimens for expert appraisal.[46] Despite suffering badly from seasickness, Darwin wrote copious notes while on board the ship. Most of his zoology notes are about marine invertebrates, starting with plankton collected in a calm spell.[44][47]

On their first stop ashore at St Jago in Cape Verde, Darwin found that a white band high in the volcanic rock cliffs included seashells. FitzRoy had given him the first volume of Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology, which set out uniformitarian concepts of land slowly rising or falling over immense periods,[II] and Darwin saw things Lyell's way, theorising and thinking of writing a book on geology.[48] When they reached Brazil, Darwin was delighted by the tropical forest,[49] but detested the sight of slavery, and disputed this issue with Fitzroy.[50]

The survey continued to the south in Patagonia. They stopped at Bahía Blanca, and in cliffs near Punta Alta Darwin made a major find of fossil bones of huge extinct mammals beside modern seashells, indicating recent extinction with no signs of change in climate or catastrophe. He identified the little-known Megatherium by a tooth and its association with bony armour, which had at first seemed to him to be like a giant version of the armour on local armadillos. The finds brought great interest when they reached England.[51][52]

On rides with gauchos into the interior to explore geology and collect more fossils, Darwin gained social, political and anthropological insights into both native and colonial people at a time of revolution, and learnt that two types of rhea had separate but overlapping territories.[53][54] Further south, he saw stepped plains of shingle and seashells as raised beaches showing a series of elevations. He read Lyell's second volume and accepted its view of "centres of creation" of species, but his discoveries and theorising challenged Lyell's ideas of smooth continuity and of extinction of species.[55][56]

Three Fuegians on board had been seized during the first Beagle voyage, then during a year in England were educated as missionaries. Darwin found them friendly and civilised, yet at Tierra del Fuego he met "miserable, degraded savages", as different as wild from domesticated animals.[57] He remained convinced that, despite this diversity, all humans were interrelated with a shared origin and potential for improvement towards civilisation. Unlike his scientist friends, he now thought there was no unbridgeable gap between humans and animals.[58] A year on, the mission had been abandoned. The Fuegian they had named Jemmy Button lived like the other natives, had a wife, and had no wish to return to England.[59]

Darwin experienced an earthquake in Chile in 1835 and saw signs that the land had just been raised, including mussel-beds stranded above high tide. High in the Andes he saw seashells, and several fossil trees that had grown on a sand beach. He theorised that as the land rose, oceanic islands sank, and coral reefs round them grew to form atolls.[60][61]

On the geologically new Galápagos Islands, Darwin looked for evidence attaching wildlife to an older "centre of creation", and found mockingbirds allied to those in Chile but differing from island to island. He heard that slight variations in the shape of tortoise shells showed which island they came from, but failed to collect them, even after eating tortoises taken on board as food.[62][63] In Australia, the marsupial rat-kangaroo and the platypus seemed so unusual that Darwin thought it was almost as though two distinct Creators had been at work.[64] He found the Aborigines "good-humoured & pleasant", and noted their depletion by European settlement.[65]

FitzRoy investigated how the atolls of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands had formed, and the survey supported Darwin's theorising.[61] FitzRoy began writing the official Narrative of the Beagle voyages, and after reading Darwin's diary he proposed incorporating it into the account.[66] Darwin's Journal was eventually rewritten as a separate third volume, on natural history.[67]

In Cape Town, South Africa, Darwin and FitzRoy met John Herschel, who had recently written to Lyell praising his uniformitarianism as opening bold speculation on "that mystery of mysteries, the replacement of extinct species by others" as "a natural in contradistinction to a miraculous process".[68] When organising his notes as the ship sailed home, Darwin wrote that, if his growing suspicions about the mockingbirds, the tortoises and the Falkland Islands fox were correct, "such facts undermine the stability of Species", then cautiously added "would" before "undermine".[69] He later wrote that such facts "seemed to me to throw some light on the origin of species".[70]

Inception of Darwin's evolutionary theory

By the time Darwin returned to England, he was already a celebrity in scientific circles as in December 1835 Henslow had fostered his former pupil's reputation by publishing a pamphlet of Darwin's geological letters for select naturalists.[71] On 2 October 1836 the ship anchored at Falmouth, Cornwall. Darwin promptly made the long coach journey to Shrewsbury to visit his home and see relatives. He then hurried to Cambridge to see Henslow, who advised him on finding naturalists available to catalogue Darwin's animal collections and who agreed to take on the botanical specimens. Darwin's father organised investments, enabling his son to be a self-funded gentleman scientist, and an excited Darwin went round the London institutions being fêted and seeking experts to describe the collections. British zoologists at the time had a huge backlog of work due to natural history collecting being promoted and encouraged through the British Empire, and there was a danger of specimens just being left in storage.[72]

Charles Lyell eagerly met Darwin for the first time on 29 October and soon introduced him to the up-and-coming anatomist Richard Owen, who had the facilities of the Royal College of Surgeons to work on the fossil bones collected by Darwin. Owen's surprising results included other gigantic extinct ground sloths as well as the Megatherium, a near complete skeleton of the unknown Scelidotherium and a hippopotamus-sized rodent-like skull named Toxodon resembling a giant capybara. The armour fragments were actually from Glyptodon, a huge armadillo-like creature as Darwin had initially thought.[73][52] These extinct creatures were related to living species in South America.[74]

In mid-December, Darwin took lodgings in Cambridge to organise work on his collections and rewrite his Journal.[75] He wrote his first paper, showing that the South American landmass was slowly rising, and with Lyell's enthusiastic backing read it to the Geological Society of London on 4 January 1837. On the same day, he presented his mammal and bird specimens to the Zoological Society. The ornithologist John Gould soon announced that the Galapagos birds that Darwin had thought a mixture of blackbirds, "gros-beaks" and finches, were, in fact, twelve separate species of finches. On 17 February, Darwin was elected to the Council of the Geological Society, and Lyell's presidential address presented Owen's findings on Darwin's fossils, stressing geographical continuity of species as supporting his uniformitarian ideas.[76]

Early in March, Darwin moved to London to be near this work, joining Lyell's social circle of scientists and experts such as Charles Babbage,[77] who described God as a programmer of laws. Darwin stayed with his freethinking brother Erasmus, part of this Whig circle and a close friend of the writer Harriet Martineau, who promoted Malthusianism underlying the controversial Whig Poor Law reforms to stop welfare from causing overpopulation and more poverty. As a Unitarian, she welcomed the radical implications of transmutation of species, promoted by Grant and younger surgeons influenced by Geoffroy. Transmutation was anathema to Anglicans defending social order,[78] but reputable scientists openly discussed the subject and there was wide interest in John Herschel's letter praising Lyell's approach as a way to find a natural cause of the origin of new species.[68]

Gould met Darwin and told him that the Galápagos mockingbirds from different islands were separate species, not just varieties, and what Darwin had thought was a "wren" was also in the finch group. Darwin had not labelled the finches by island, but from the notes of others on the ship, including FitzRoy, he allocated species to islands.[79] The two rheas were also distinct species, and on 14 March Darwin announced how their distribution changed going southwards.[80]

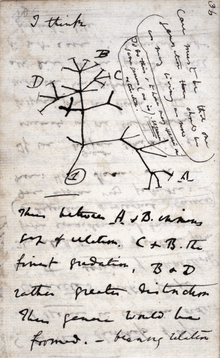

By mid-March 1837, barely six months after his return to England, Darwin was speculating in his Red Notebook on the possibility that "one species does change into another" to explain the geographical distribution of living species such as the rheas, and extinct ones such as the strange extinct mammal Macrauchenia, which resembled a giant guanaco, a llama relative. His thoughts on lifespan, asexual reproduction and sexual reproduction developed in his "B" notebook around mid-July on to variation in offspring "to adapt & alter the race to changing world" explaining the Galápagos tortoises, mockingbirds and rheas. He sketched branching descent, then a genealogical branching of a single evolutionary tree, in which "It is absurd to talk of one animal being higher than another", discarding Lamarck's independent lineages progressing to higher forms.[81]

Overwork, illness, and marriage

While developing this intensive study of transmutation, Darwin became mired in more work. Still rewriting his Journal, he took on editing and publishing the expert reports on his collections, and with Henslow's help obtained a Treasury grant of £1,000 to sponsor this multi-volume Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, a sum equivalent to about £92,000 in 2018.[82] He stretched the funding to include his planned books on geology, and agreed to unrealistic dates with the publisher.[83] As the Victorian era began, Darwin pressed on with writing his Journal, and in August 1837 began correcting printer's proofs.[84]

As Darwin worked under pressure, his health suffered. On 20 September he had "an uncomfortable palpitation of the heart", so his doctors urged him to "knock off all work" and live in the country for a few weeks. After visiting Shrewsbury he joined his Wedgwood relatives at Maer Hall, Staffordshire, but found them too eager for tales of his travels to give him much rest. His charming, intelligent, and cultured cousin Emma Wedgwood, nine months older than Darwin, was nursing his invalid aunt. His uncle Josiah pointed out an area of ground where cinders had disappeared under loam and suggested that this might have been the work of earthworms, inspiring "a new & important theory" on their role in soil formation, which Darwin presented at the Geological Society on 1 November 1837.[85]

William Whewell pushed Darwin to take on the duties of Secretary of the Geological Society. After initially declining the work, he accepted the post in March 1838.[86] Despite the grind of writing and editing the Beagle reports, Darwin made remarkable progress on transmutation, taking every opportunity to question expert naturalists and, unconventionally, people with practical experience in selective breeding such as farmers and pigeon fanciers.[13][87] Over time, his research drew on information from his relatives and children, the family butler, neighbours, colonists and former shipmates.[88] He included mankind in his speculations from the outset, and on seeing an orangutan in the zoo on 28 March 1838 noted its childlike behaviour.[89]

The strain took a toll, and by June he was being laid up for days on end with stomach problems, headaches and heart symptoms. For the rest of his life, he was repeatedly incapacitated with episodes of stomach pains, vomiting, severe boils, palpitations, trembling and other symptoms, particularly during times of stress, such as attending meetings or making social visits. The cause of Darwin's illness remained unknown, and attempts at treatment had only ephemeral success.[90]

On 23 June, he took a break and went "geologising" in Scotland. He visited Glen Roy in glorious weather to see the parallel "roads" cut into the hillsides at three heights. He later published his view that these were marine raised beaches, but then had to accept that they were shorelines of a proglacial lake.[91]

Fully recuperated, he returned to Shrewsbury in July. Used to jotting down daily notes on animal breeding, he scrawled rambling thoughts about marriage, career and prospects on two scraps of paper, one with columns headed "Marry" and "Not Marry". Advantages under "Marry" included "constant companion and a friend in old age ... better than a dog anyhow", against points such as "less money for books" and "terrible loss of time."[92] Having decided in favour of marriage, he discussed it with his father, then went to visit his cousin Emma on 29 July. He did not get around to proposing, but against his father's advice he mentioned his ideas on transmutation.[93]

Malthus and natural selection

Continuing his research in London, Darwin's wide reading now included the sixth edition of Malthus's An Essay on the Principle of Population, and on 28 September 1838 he noted its assertion that human "population, when unchecked, goes on doubling itself every twenty five years, or increases in a geometrical ratio", a geometric progression so that population soon exceeds food supply in what is known as a Malthusian catastrophe. Darwin was well prepared to compare this to de Candolle's "warring of the species" of plants and the struggle for existence among wildlife, explaining how numbers of a species kept roughly stable. As species always breed beyond available resources, favourable variations would make organisms better at surviving and passing the variations on to their offspring, while unfavourable variations would be lost. He wrote that the "final cause of all this wedging, must be to sort out proper structure, & adapt it to changes", so that "One may say there is a force like a hundred thousand wedges trying force into every kind of adapted structure into the gaps of in the economy of nature, or rather forming gaps by thrusting out weaker ones."[13][94] This would result in the formation of new species.[13][95] As he later wrote in his Autobiography:

In October 1838, that is, fifteen months after I had begun my systematic enquiry, I happened to read for amusement Malthus on Population, and being well prepared to appreciate the struggle for existence which everywhere goes on from long-continued observation of the habits of animals and plants, it at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species. Here, then, I had at last got a theory by which to work...[96]

By mid-December, Darwin saw a similarity between farmers picking the best stock in selective breeding, and a Malthusian Nature selecting from chance variants so that "every part of newly acquired structure is fully practical and perfected",[97] thinking this comparison "a beautiful part of my theory".[98] He later called his theory natural selection, an analogy with what he termed the "artificial selection" of selective breeding.[13]

On 11 November, he returned to Maer and proposed to Emma, once more telling her his ideas. She accepted, then in exchanges of loving letters she showed how she valued his openness in sharing their differences, also expressing her strong Unitarian beliefs and concerns that his honest doubts might separate them in the afterlife.[99] While he was house-hunting in London, bouts of illness continued and Emma wrote urging him to get some rest, almost prophetically remarking "So don't be ill any more my dear Charley till I can be with you to nurse you." He found what they called "Macaw Cottage" (because of its gaudy interiors) in Gower Street, then moved his "museum" in over Christmas. On 24 January 1839, Darwin was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS).[2][100]

On 29 January, Darwin and Emma Wedgwood were married at Maer in an Anglican ceremony arranged to suit the Unitarians, then immediately caught the train to London and their new home.[101]

Geology books, barnacles, evolutionary research

Darwin now had the framework of his theory of natural selection "by which to work",[96] as his "prime hobby".[102] His research included extensive experimental selective breeding of plants and animals, finding evidence that species were not fixed and investigating many detailed ideas to refine and substantiate his theory.[13] For fifteen years this work was in the background to his main occupation of writing on geology and publishing expert reports on the Beagle collections, and in particular, the barnacles.[103]

When FitzRoy's Narrative was published in May 1839, Darwin's Journal and Remarks was such a success as the third volume that later that year it was published on its own.[104] Early in 1842, Darwin wrote about his ideas to Charles Lyell, who noted that his ally "denies seeing a beginning to each crop of species".[105]

Darwin's book The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs on his theory of atoll formation was published in May 1842 after more than three years of work, and he then wrote his first "pencil sketch" of his theory of natural selection.[106] To escape the pressures of London, the family moved to rural Down House in September.[107] On 11 January 1844, Darwin mentioned his theorising to the botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker, writing with melodramatic humour "it is like confessing a murder".[108][109] Hooker replied "There may in my opinion have been a series of productions on different spots, & also a gradual change of species. I shall be delighted to hear how you think that this change may have taken place, as no presently conceived opinions satisfy me on the subject."[110]

By July, Darwin had expanded his "sketch" into a 230-page "Essay", to be expanded with his research results if he died prematurely.[112] In November, the anonymously published sensational best-seller Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation brought wide interest in transmutation. Darwin scorned its amateurish geology and zoology, but carefully reviewed his own arguments. Controversy erupted, and it continued to sell well despite contemptuous dismissal by scientists.[113][114]

Darwin completed his third geological book in 1846. He now renewed a fascination and expertise in marine invertebrates, dating back to his student days with Grant, by dissecting and classifying the barnacles he had collected on the voyage, enjoying observing beautiful structures and thinking about comparisons with allied structures.[115] In 1847, Hooker read the "Essay" and sent notes that provided Darwin with the calm critical feedback that he needed, but would not commit himself and questioned Darwin's opposition to continuing acts of creation.[116]

In an attempt to improve his chronic ill health, Darwin went in 1849 to Dr. James Gully's Malvern spa and was surprised to find some benefit from hydrotherapy.[117] Then, in 1851, his treasured daughter Annie fell ill, reawakening his fears that his illness might be hereditary, and after a long series of crises she died.[118]

In eight years of work on barnacles (Cirripedia), Darwin's theory helped him to find "homologies" showing that slightly changed body parts served different functions to meet new conditions, and in some genera he found minute males parasitic on hermaphrodites, showing an intermediate stage in evolution of distinct sexes.[119] In 1853, it earned him the Royal Society's Royal Medal, and it made his reputation as a biologist.[120] In 1854 he became a Fellow of the Linnean Society of London, gaining postal access to its library.[121] He began a major reassessment of his theory of species, and in November realised that divergence in the character of descendants could be explained by them becoming adapted to "diversified places in the economy of nature".[122]

Publication of the theory of natural selection

By the start of 1856, Darwin was investigating whether eggs and seeds could survive travel across seawater to spread species across oceans. Hooker increasingly doubted the traditional view that species were fixed, but their young friend Thomas Henry Huxley was still firmly against the transmutation of species. Lyell was intrigued by Darwin's speculations without realising their extent. When he read a paper by Alfred Russel Wallace, "On the Law which has Regulated the Introduction of New Species", he saw similarities with Darwin's thoughts and urged him to publish to establish precedence. Though Darwin saw no threat, on 14 May 1856 he began writing a short paper. Finding answers to difficult questions held him up repeatedly, and he expanded his plans to a "big book on species" titled Natural Selection, which was to include his "note on Man". He continued his researches, obtaining information and specimens from naturalists worldwide including Wallace who was working in Borneo. In mid-1857 he added a section heading; "Theory applied to Races of Man", but did not add text on this topic. On 5 September 1857, Darwin sent the American botanist Asa Gray a detailed outline of his ideas, including an abstract of Natural Selection, which omitted human origins and sexual selection. In December, Darwin received a letter from Wallace asking if the book would examine human origins. He responded that he would avoid that subject, "so surrounded with prejudices", while encouraging Wallace's theorising and adding that "I go much further than you."[124]

Darwin's book was only partly written when, on 18 June 1858, he received a paper from Wallace describing natural selection. Shocked that he had been "forestalled", Darwin sent it on that day to Lyell, as requested by Wallace,[125][126] and although Wallace had not asked for publication, Darwin suggested he would send it to any journal that Wallace chose. His family was in crisis with children in the village dying of scarlet fever, and he put matters in the hands of his friends. After some discussion, with no reliable way of involving Wallace, Lyell and Hooker decided on a joint presentation at the Linnean Society on 1 July of On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection. On the evening of 28 June, Darwin's baby son died of scarlet fever after almost a week of severe illness, and he was too distraught to attend.[127]

There was little immediate attention to this announcement of the theory; the president of the Linnean Society remarked in May 1859 that the year had not been marked by any revolutionary discoveries.[128] Only one review rankled enough for Darwin to recall it later; Professor Samuel Haughton of Dublin claimed that "all that was new in them was false, and what was true was old".[129] Darwin struggled for thirteen months to produce an abstract of his "big book", suffering from ill health but getting constant encouragement from his scientific friends. Lyell arranged to have it published by John Murray.[130]

On the Origin of Species proved unexpectedly popular, with the entire stock of 1,250 copies oversubscribed when it went on sale to booksellers on 22 November 1859.[131] In the book, Darwin set out "one long argument" of detailed observations, inferences and consideration of anticipated objections.[132] In making the case for common descent, he included evidence of homologies between humans and other mammals.[133][III] Having outlined sexual selection, he hinted that it could explain differences between human races.[134][IV] He avoided explicit discussion of human origins, but implied the significance of his work with the sentence; "Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history."[135][IV] His theory is simply stated in the introduction:

As many more individuals of each species are born than can possibly survive; and as, consequently, there is a frequently recurring struggle for existence, it follows that any being, if it vary however slightly in any manner profitable to itself, under the complex and sometimes varying conditions of life, will have a better chance of surviving, and thus be naturally selected. From the strong principle of inheritance, any selected variety will tend to propagate its new and modified form.[136]

At the end of the book he concluded that:

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.[137]

The last word was the only variant of "evolved" in the first five editions of the book. "Evolutionism" at that time was associated with other concepts, most commonly with embryological development, and Darwin first used the word evolution in The Descent of Man in 1871, before adding it in 1872 to the 6th edition of The Origin of Species.[138]

Responses to publication

The book aroused international interest, with less controversy than had greeted the popular and less scientific Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation.[140] Though Darwin's illness kept him away from the public debates, he eagerly scrutinised the scientific response, commenting on press cuttings, reviews, articles, satires and caricatures, and corresponded on it with colleagues worldwide.[141] The book did not explicitly discuss human origins,[135][IV] but included a number of hints about the animal ancestry of humans from which the inference could be made.[142] The first review asked, "If a monkey has become a man–what may not a man become?" and said it should be left to theologians as it was too dangerous for ordinary readers.[143] Amongst early favourable responses, Huxley's reviews swiped at Richard Owen, leader of the scientific establishment Huxley was trying to overthrow.[144] In April, Owen's review attacked Darwin's friends and condescendingly dismissed his ideas, angering Darwin,[145] but Owen and others began to promote ideas of supernaturally guided evolution. Patrick Matthew drew attention to his 1831 book which had a brief appendix suggesting a concept of natural selection leading to new species, but he had not developed the idea.[146]

The Church of England's response was mixed. Darwin's old Cambridge tutors Sedgwick and Henslow dismissed the ideas, but liberal clergymen interpreted natural selection as an instrument of God's design, with the cleric Charles Kingsley seeing it as "just as noble a conception of Deity".[147] In 1860, the publication of Essays and Reviews by seven liberal Anglican theologians diverted clerical attention from Darwin, with its ideas including higher criticism attacked by church authorities as heresy. In it, Baden Powell argued that miracles broke God's laws, so belief in them was atheistic, and praised "Mr Darwin's masterly volume [supporting] the grand principle of the self-evolving powers of nature".[148] Asa Gray discussed teleology with Darwin, who imported and distributed Gray's pamphlet on theistic evolution, Natural Selection is not inconsistent with natural theology.[147][149] The most famous confrontation was at the public 1860 Oxford evolution debate during a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, where the Bishop of Oxford Samuel Wilberforce, though not opposed to transmutation of species, argued against Darwin's explanation and human descent from apes. Joseph Hooker argued strongly for Darwin, and Thomas Huxley's legendary retort, that he would rather be descended from an ape than a man who misused his gifts, came to symbolise a triumph of science over religion.[147][150]

Even Darwin's close friends Gray, Hooker, Huxley and Lyell still expressed various reservations but gave strong support, as did many others, particularly younger naturalists. Gray and Lyell sought reconciliation with faith, while Huxley portrayed a polarisation between religion and science. He campaigned pugnaciously against the authority of the clergy in education,[147] aiming to overturn the dominance of clergymen and aristocratic amateurs under Owen in favour of a new generation of professional scientists. Owen's claim that brain anatomy proved humans to be a separate biological order from apes was shown to be false by Huxley in a long running dispute parodied by Kingsley as the "Great Hippocampus Question", and discredited Owen.[151]

Darwinism became a movement covering a wide range of evolutionary ideas. In 1863 Lyell's Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man popularised prehistory, though his caution on evolution disappointed Darwin. Weeks later Huxley's Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature showed that anatomically, humans are apes, then The Naturalist on the River Amazons by Henry Walter Bates provided empirical evidence of natural selection.[152] Lobbying brought Darwin Britain's highest scientific honour, the Royal Society's Copley Medal, awarded on 3 November 1864.[153] That day, Huxley held the first meeting of what became the influential "X Club" devoted to "science, pure and free, untrammelled by religious dogmas".[154] By the end of the decade most scientists agreed that evolution occurred, but only a minority supported Darwin's view that the chief mechanism was natural selection.[155]

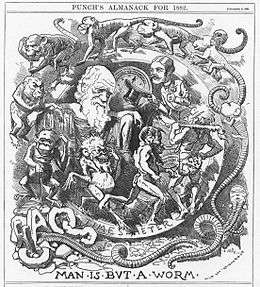

The Origin of Species was translated into many languages, becoming a staple scientific text attracting thoughtful attention from all walks of life, including the "working men" who flocked to Huxley's lectures.[156] Darwin's theory also resonated with various movements at the time[V] and became a key fixture of popular culture.[VI] Cartoonists parodied animal ancestry in an old tradition of showing humans with animal traits, and in Britain these droll images served to popularise Darwin's theory in an unthreatening way. While ill in 1862 Darwin began growing a beard, and when he reappeared in public in 1866 caricatures of him as an ape helped to identify all forms of evolutionism with Darwinism.[139]

Descent of Man, sexual selection, and botany

Despite repeated bouts of illness during the last twenty-two years of his life, Darwin's work continued. Having published On the Origin of Species as an abstract of his theory, he pressed on with experiments, research, and writing of his "big book". He covered human descent from earlier animals including evolution of society and of mental abilities, as well as explaining decorative beauty in wildlife and diversifying into innovative plant studies.

Enquiries about insect pollination led in 1861 to novel studies of wild orchids, showing adaptation of their flowers to attract specific moths to each species and ensure cross fertilisation. In 1862 Fertilisation of Orchids gave his first detailed demonstration of the power of natural selection to explain complex ecological relationships, making testable predictions. As his health declined, he lay on his sickbed in a room filled with inventive experiments to trace the movements of climbing plants.[157] Admiring visitors included Ernst Haeckel, a zealous proponent of Darwinismus incorporating Lamarckism and Goethe's idealism.[158] Wallace remained supportive, though he increasingly turned to Spiritualism.[159]

Darwin's book The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (1868) was the first part of his planned "big book", and included his unsuccessful hypothesis of pangenesis attempting to explain heredity. It sold briskly at first, despite its size, and was translated into many languages. He wrote most of a second part, on natural selection, but it remained unpublished in his lifetime.[160]

Lyell had already popularised human prehistory, and Huxley had shown that anatomically humans are apes.[152] With The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex published in 1871, Darwin set out evidence from numerous sources that humans are animals, showing continuity of physical and mental attributes, and presented sexual selection to explain impractical animal features such as the peacock's plumage as well as human evolution of culture, differences between sexes, and physical and cultural racial classification, while emphasising that humans are all one species.[161] His research using images was expanded in his 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, one of the first books to feature printed photographs, which discussed the evolution of human psychology and its continuity with the behaviour of animals. Both books proved very popular, and Darwin was impressed by the general assent with which his views had been received, remarking that "everybody is talking about it without being shocked."[162] His conclusion was "that man with all his noble qualities, with sympathy which feels for the most debased, with benevolence which extends not only to other men but to the humblest living creature, with his god-like intellect which has penetrated into the movements and constitution of the solar system—with all these exalted powers—Man still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin."[163]

His evolution-related experiments and investigations led to books on Orchids, Insectivorous Plants, The Effects of Cross and Self Fertilisation in the Vegetable Kingdom, different forms of flowers on plants of the same species, and The Power of Movement in Plants. He continued to collect information and exchange views from scientific correspondents all over the world, including Mary Treat, whom he encouraged to persevere in her scientific work.[164] His botanical work[IX] was interpreted and popularised by various writers including Grant Allen and H. G. Wells, and helped transform plant science in the late 19th century and early 20th century. In his last book he returned to The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms.

Death and funeral

In 1882 he was diagnosed with what was called "angina pectoris" which then meant coronary thrombosis and disease of the heart. At the time of his death, the physicians diagnosed "anginal attacks", and "heart-failure".[165] It has been speculated that Darwin may have suffered from chronic Chagas disease.[166] This speculation is based on a journal entry written by Darwin, describing he was bitten by the "Kissing Bug" in Mendoza, Argentina, in 1835;[167] and based on the constellation of clinical symptoms he exhibited, including cardiac disease which is a hallmark of chronic Chagas disease.[168][166] Exhuming Darwin's body is likely necessary to definitively determine his state of infection by detecting DNA of infecting parasite, T. cruzi, that causes Chagas disease.[166][167]

He died at Down House on 19 April 1882. His last words were to his family, telling Emma "I am not the least afraid of death—Remember what a good wife you have been to me—Tell all my children to remember how good they have been to me", then while she rested, he repeatedly told Henrietta and Francis "It's almost worth while to be sick to be nursed by you".[169] He had expected to be buried in St Mary's churchyard at Downe, but at the request of Darwin's colleagues, after public and parliamentary petitioning, William Spottiswoode (President of the Royal Society) arranged for Darwin to be honoured by burial in Westminster Abbey, close to John Herschel and Isaac Newton. The funeral was held on Wednesday 26 April and was attended by thousands of people, including family, friends, scientists, philosophers and dignitaries.[170][10]

Legacy

By the time of his death, Darwin and his colleagues had convinced most scientists that evolution as descent with modification was correct, and he was regarded as a great scientist who had revolutionised ideas. In June 1909, though few at that time agreed with his view that "natural selection has been the main but not the exclusive means of modification", he was honoured by more than 400 officials and scientists from across the world who met in Cambridge to commemorate his centenary and the fiftieth anniversary of On the Origin of Species.[171] Around the beginning of the 20th century, a period that has been called "the eclipse of Darwinism", scientists proposed various alternative evolutionary mechanisms, which eventually proved untenable. Ronald Fisher, an English statistician, finally united Mendelian genetics with natural selection, in the period between 1918 and his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection.[172] He gave the theory a mathematical footing and brought broad scientific consensus that natural selection was the basic mechanism of evolution, thus founding the basis for population genetics and the modern evolutionary synthesis, with J.B.S. Haldane and Sewall Wright, which set the frame of reference for modern debates and refinements of the theory.[14]

Commemoration

During Darwin's lifetime, many geographical features were given his name. An expanse of water adjoining the Beagle Channel was named Darwin Sound by Robert FitzRoy after Darwin's prompt action, along with two or three of the men, saved them from being marooned on a nearby shore when a collapsing glacier caused a large wave that would have swept away their boats,[173] and the nearby Mount Darwin in the Andes was named in celebration of Darwin's 25th birthday.[174] When the Beagle was surveying Australia in 1839, Darwin's friend John Lort Stokes sighted a natural harbour which the ship's captain Wickham named Port Darwin: a nearby settlement was renamed Darwin in 1911, and it became the capital city of Australia's Northern Territory.[175]

Stephen Heard identified 389 species that have been named after Darwin,[176] and there are at least 9 genera.[177] In one example, the group of tanagers related to those Darwin found in the Galápagos Islands became popularly known as "Darwin's finches" in 1947, fostering inaccurate legends about their significance to his work.[178]

Darwin's work has continued to be celebrated by numerous publications and events. The Linnean Society of London has commemorated Darwin's achievements by the award of the Darwin–Wallace Medal since 1908. Darwin Day has become an annual celebration, and in 2009 worldwide events were arranged for the bicentenary of Darwin's birth and the 150th anniversary of the publication of On the Origin of Species.[179]

Darwin has been commemorated in the UK, with his portrait printed on the reverse of £10 banknotes printed along with a hummingbird and HMS Beagle, issued by the Bank of England.[180]

A life-size seated statue of Darwin can be seen in the main hall of the Natural History Museum in London.[181]

A seated statue of Darwin, unveiled 1897, stands in front of Shrewsbury Library, the building that used to house Shrewsbury School, which Darwin attended as a boy. Another statue of Darwin as a young man is situated in the grounds of Christ's College, Cambridge.

Darwin College, a postgraduate college at Cambridge University, is named after the Darwin family.[182]

In 2008–09, the Swedish band The Knife, in collaboration with Danish performance group Hotel Pro Forma and other musicians from Denmark, Sweden and the US, created an opera about the life of Darwin, and The Origin of Species, titled Tomorrow, in a Year. The show toured European theatres in 2010.

Children

| William Erasmus | 27 December 1839 – | 8 September 1914 |

| Anne Elizabeth | 2 March 1841 – | 23 April 1851 |

| Mary Eleanor | 23 September 1842 – | 16 October 1842 |

| Henrietta Emma | 25 September 1843 – | 17 December 1927 |

| George Howard | 9 July 1845 – | 7 December 1912 |

| Elizabeth | 8 July 1847 – | 8 June 1926 |

| Francis | 16 August 1848 – | 19 September 1925 |

| Leonard | 15 January 1850 – | 26 March 1943 |

| Horace | 13 May 1851 – | 29 September 1928 |

| Charles | 6 December 1856 – | 28 June 1858 |

The Darwins had ten children: two died in infancy, and Annie's death at the age of ten had a devastating effect on her parents. Charles was a devoted father and uncommonly attentive to his children.[17] Whenever they fell ill, he feared that they might have inherited weaknesses from inbreeding due to the close family ties he shared with his wife and cousin, Emma Wedgwood.

He examined inbreeding in his writings, contrasting it with the advantages of outcrossing in many species.[183] Despite his fears, most of the surviving children and many of their descendants went on to have distinguished careers.

Of his surviving children, George, Francis and Horace became Fellows of the Royal Society,[184] distinguished as astronomer,[185] botanist and civil engineer, respectively. All three were knighted.[186] Another son, Leonard, went on to be a soldier, politician, economist, eugenicist and mentor of the statistician and evolutionary biologist Ronald Fisher.[187]

Views and opinions

Religious views

Darwin's family tradition was nonconformist Unitarianism, while his father and grandfather were freethinkers, and his baptism and boarding school were Church of England.[27] When going to Cambridge to become an Anglican clergyman, he did not doubt the literal truth of the Bible.[36] He learned John Herschel's science which, like William Paley's natural theology, sought explanations in laws of nature rather than miracles and saw adaptation of species as evidence of design.[38][39] On board HMS Beagle, Darwin was quite orthodox and would quote the Bible as an authority on morality.[189] He looked for "centres of creation" to explain distribution,[62] and suggested that the very similar antlions found in Australia and England were evidence of a divine hand.[64]

By his return, he was critical of the Bible as history, and wondered why all religions should not be equally valid.[189] In the next few years, while intensively speculating on geology and the transmutation of species, he gave much thought to religion and openly discussed this with his wife Emma, whose beliefs also came from intensive study and questioning.[99] The theodicy of Paley and Thomas Malthus vindicated evils such as starvation as a result of a benevolent creator's laws, which had an overall good effect. To Darwin, natural selection produced the good of adaptation but removed the need for design,[190] and he could not see the work of an omnipotent deity in all the pain and suffering, such as the ichneumon wasp paralysing caterpillars as live food for its eggs.[149] Though he thought of religion as a tribal survival strategy, Darwin was reluctant to give up the idea of God as an ultimate lawgiver. He was increasingly troubled by the problem of evil.[191][192]

Darwin remained close friends with the vicar of Downe, John Brodie Innes, and continued to play a leading part in the parish work of the church,[193] but from around 1849 would go for a walk on Sundays while his family attended church.[188] He considered it "absurd to doubt that a man might be an ardent theist and an evolutionist"[194][195] and, though reticent about his religious views, in 1879 he wrote that "I have never been an atheist in the sense of denying the existence of a God. – I think that generally ... an agnostic would be the most correct description of my state of mind".[99][194]

The "Lady Hope Story", published in 1915, claimed that Darwin had reverted to Christianity on his sickbed. The claims were repudiated by Darwin's children and have been dismissed as false by historians.[196]

Human society

Darwin's views on social and political issues reflected his time and social position. He grew up in a family of Whig reformers who, like his uncle Josiah Wedgwood, supported electoral reform and the emancipation of slaves. Darwin was passionately opposed to slavery, while seeing no problem with the working conditions of English factory workers or servants. His taxidermy lessons in 1826 from the freed slave John Edmonstone, whom he long recalled as "a very pleasant and intelligent man", reinforced his belief that black people shared the same feelings, and could be as intelligent as people of other races. He took the same attitude to native people he met on the Beagle voyage.[197] These attitudes were not unusual in Britain in the 1820s, much as it shocked visiting Americans. British society started to envisage racial differences more vivedly in mid-century,[28] but Darwin remained strongly against slavery, against "ranking the so-called races of man as distinct species", and against ill-treatment of native people.[198][VII] Darwins interaction with Yaghans (Fuegians) such as Jemmy Button during the second voyage of HMS Beagle had a profound impact on his view of primitive peoples. At his arrival to Tierra del Fuego he made a colourful description of "Fuegian savages".[199] This view changed as he came to know Yaghan people more in detail. By studying the Yaghans, Darwin concluded that a number of basic emotions by different human groups were the same and that mental capabilities were roughly the same as for Europeans.[199] While interested in Yaghan culture Darwin failed to appreciate their deep ecological knowledge and elaborate cosmology until the 1850s when he inspected a dictionary of Yaghan detailing 32-thousand words.[199] He saw that European colonisation would often lead to the extinction of native civilisations, and "tr[ied] to integrate colonialism into an evolutionary history of civilization analogous to natural history."[200]

He thought men's eminence over women was the outcome of sexual selection, a view disputed by Antoinette Brown Blackwell in her 1875 book The Sexes Throughout Nature.[201]

Darwin was intrigued by his half-cousin Francis Galton's argument, introduced in 1865, that statistical analysis of heredity showed that moral and mental human traits could be inherited, and principles of animal breeding could apply to humans. In The Descent of Man, Darwin noted that aiding the weak to survive and have families could lose the benefits of natural selection, but cautioned that withholding such aid would endanger the instinct of sympathy, "the noblest part of our nature", and factors such as education could be more important. When Galton suggested that publishing research could encourage intermarriage within a "caste" of "those who are naturally gifted", Darwin foresaw practical difficulties, and thought it "the sole feasible, yet I fear utopian, plan of procedure in improving the human race", preferring to simply publicise the importance of inheritance and leave decisions to individuals.[202] Francis Galton named this field of study "eugenics" in 1883.[VIII] After Darwin's death, his theories were cited to promote eugenic policies that went against his humanitarian principles.[200]

Evolutionary social movements

Darwin's fame and popularity led to his name being associated with ideas and movements that, at times, had only an indirect relation to his writings, and sometimes went directly against his express comments.

Thomas Malthus had argued that population growth beyond resources was ordained by God to get humans to work productively and show restraint in getting families; this was used in the 1830s to justify workhouses and laissez-faire economics.[203] Evolution was by then seen as having social implications, and Herbert Spencer's 1851 book Social Statics based ideas of human freedom and individual liberties on his Lamarckian evolutionary theory.[204]

Soon after the Origin was published in 1859, critics derided his description of a struggle for existence as a Malthusian justification for the English industrial capitalism of the time. The term Darwinism was used for the evolutionary ideas of others, including Spencer's "survival of the fittest" as free-market progress, and Ernst Haeckel's polygenistic ideas of human development. Writers used natural selection to argue for various, often contradictory, ideologies such as laissez-faire dog-eat-dog capitalism, colonialism and imperialism. However, Darwin's holistic view of nature included "dependence of one being on another"; thus pacifists, socialists, liberal social reformers and anarchists such as Peter Kropotkin stressed the value of co-operation over struggle within a species.[205] Darwin himself insisted that social policy should not simply be guided by concepts of struggle and selection in nature.[206]

After the 1880s, a eugenics movement developed on ideas of biological inheritance, and for scientific justification of their ideas appealed to some concepts of Darwinism. In Britain, most shared Darwin's cautious views on voluntary improvement and sought to encourage those with good traits in "positive eugenics". During the "Eclipse of Darwinism", a scientific foundation for eugenics was provided by Mendelian genetics. Negative eugenics to remove the "feebleminded" were popular in America, Canada and Australia, and eugenics in the United States introduced compulsory sterilisation laws, followed by several other countries. Subsequently, Nazi eugenics brought the field into disrepute.[VIII]

The term "Social Darwinism" was used infrequently from around the 1890s, but became popular as a derogatory term in the 1940s when used by Richard Hofstadter to attack the laissez-faire conservatism of those like William Graham Sumner who opposed reform and socialism. Since then, it has been used as a term of abuse by those opposed to what they think are the moral consequences of evolution.[207][203]

Works

Darwin was a prolific writer. Even without publication of his works on evolution, he would have had a considerable reputation as the author of The Voyage of the Beagle, as a geologist who had published extensively on South America and had solved the puzzle of the formation of coral atolls, and as a biologist who had published the definitive work on barnacles. While On the Origin of Species dominates perceptions of his work, The Descent of Man and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals had considerable impact, and his books on plants including The Power of Movement in Plants were innovative studies of great importance, as was his final work on The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms.[208][209]

See also

- Creation–evolution controversy

- European and American voyages of scientific exploration

- History of biology

- History of evolutionary thought

- List of coupled cousins

- List of multiple discoveries

- Multiple discovery

- Portraits of Charles Darwin

- Tinamou egg

- Universal Darwinism

- 1991 Darwin

- Creation (biographical drama film)

Notes

I. ^ Darwin was eminent as a naturalist, geologist, biologist, and author. After working as a physician's assistant and two years as a medical student, he was educated as a clergyman; he was also trained in taxidermy.[210]

II. ^ Robert FitzRoy was to become known after the voyage for biblical literalism, but at this time he had considerable interest in Lyell's ideas, and they met before the voyage when Lyell asked for observations to be made in South America. FitzRoy's diary during the ascent of the River Santa Cruz in Patagonia recorded his opinion that the plains were raised beaches, but on return, newly married to a very religious lady, he recanted these ideas.(Browne 1995, pp. 186, 414)

III. ^ In the section "Morphology" of Chapter XIII of On the Origin of Species, Darwin commented on homologous bone patterns between humans and other mammals, writing: "What can be more curious than that the hand of a man, formed for grasping, that of a mole for digging, the leg of the horse, the paddle of the porpoise, and the wing of the bat, should all be constructed on the same pattern, and should include the same bones, in the same relative positions?"[211] and in the concluding chapter: "The framework of bones being the same in the hand of a man, wing of a bat, fin of the porpoise, and leg of the horse … at once explain themselves on the theory of descent with slow and slight successive modifications."[212]

IV. 1 2 3 In On the Origin of Species Darwin mentioned human origins in his concluding remark that "In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation. Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history."[135]

In "Chapter VI: Difficulties on Theory" he referred to sexual selection: "I might have adduced for this same purpose the differences between the races of man, which are so strongly marked; I may add that some little light can apparently be thrown on the origin of these differences, chiefly through sexual selection of a particular kind, but without here entering on copious details my reasoning would appear frivolous."[134]

In The Descent of Man of 1871, Darwin discussed the first passage: "During many years I collected notes on the origin or descent of man, without any intention of publishing on the subject, but rather with the determination not to publish, as I thought that I should thus only add to the prejudices against my views. It seemed to me sufficient to indicate, in the first edition of my 'Origin of Species,' that by this work 'light would be thrown on the origin of man and his history;' and this implies that man must be included with other organic beings in any general conclusion respecting his manner of appearance on this earth."[213] In a preface to the 1874 second edition, he added a reference to the second point: "it has been said by several critics, that when I found that many details of structure in man could not be explained through natural selection, I invented sexual selection; I gave, however, a tolerably clear sketch of this principle in the first edition of the 'Origin of Species,' and I there stated that it was applicable to man."[214]

V. ^ See, for example, WILLA volume 4, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Feminization of Education by Deborah M. De Simone: "Gilman shared many basic educational ideas with the generation of thinkers who matured during the period of "intellectual chaos" caused by Darwin's Origin of the Species. Marked by the belief that individuals can direct human and social evolution, many progressives came to view education as the panacea for advancing social progress and for solving such problems as urbanisation, poverty, or immigration."

VI. ^ See, for example, the song "A lady fair of lineage high" from Gilbert and Sullivan's Princess Ida, which describes the descent of man (but not woman!) from apes.

VII. ^ Darwin's belief that black people had the same essential humanity as Europeans, and had many mental similarities, was reinforced by the lessons he had from John Edmonstone in 1826.[28] Early in the Beagle voyage, Darwin nearly lost his position on the ship when he criticised FitzRoy's defence and praise of slavery. (Darwin 1958, p. 74) He wrote home about "how steadily the general feeling, as shown at elections, has been rising against Slavery. What a proud thing for England if she is the first European nation which utterly abolishes it! I was told before leaving England that after living in slave countries all my opinions would be altered; the only alteration I am aware of is forming a much higher estimate of the negro character." (Darwin 1887, p. 246) Regarding Fuegians, he "could not have believed how wide was the difference between savage and civilized man: it is greater than between a wild and domesticated animal, inasmuch as in man there is a greater power of improvement", but he knew and liked civilised Fuegians like Jemmy Button: "It seems yet wonderful to me, when I think over all his many good qualities, that he should have been of the same race, and doubtless partaken of the same character, with the miserable, degraded savages whom we first met here."(Darwin 1845, pp. 205, 207–208)

In the Descent of Man, he mentioned the similarity of Fuegians' and Edmonstone's minds to Europeans' when arguing against "ranking the so-called races of man as distinct species".[215]

He rejected the ill-treatment of native people, and for example wrote of massacres of Patagonian men, women, and children, "Every one here is fully convinced that this is the most just war, because it is against barbarians. Who would believe in this age that such atrocities could be committed in a Christian civilized country?"(Darwin 1845, p. 102)

VIII. 1 2 Geneticists studied human heredity as Mendelian inheritance, while eugenics movements sought to manage society, with a focus on social class in the United Kingdom, and on disability and ethnicity in the United States, leading to geneticists seeing this as impractical pseudoscience. A shift from voluntary arrangements to "negative" eugenics included compulsory sterilisation laws in the United States, copied by Nazi Germany as the basis for Nazi eugenics based on virulent racism and "racial hygiene".

(Thurtle, Phillip (17 December 1996). "the creation of genetic identity". SEHR. 5 (Supplement: Cultural and Technological Incubations of Fascism). Retrieved 11 November 2008.Edwards, A. W. F. (1 April 2000). "The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection". Genetics. 154 (April 2000). pp. 1419–1426. PMC 1461012. PMID 10747041. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

Wilkins, John. "Evolving Thoughts: Darwin and the Holocaust 3: eugenics". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.)

IX. ^ David Quammen writes of his "theory that [Darwin] turned to these arcane botanical studies – producing more than one book that was solidly empirical, discreetly evolutionary, yet a "horrid bore" – at least partly so that the clamorous controversialists, fighting about apes and angels and souls, would leave him... alone." David Quammen, "The Brilliant Plodder" (review of Ken Thompson, Darwin's Most Wonderful Plants: A Tour of His Botanical Legacy, University of Chicago Press, 255 pp.; Elizabeth Hennessy, On the Backs of Tortoises: Darwin, the Galápagos, and the Fate of an Evolutionary Eden, Yale University Press, 310 pp.; Bill Jenkins, Evolution Before Darwin: Theories of the Transmutation of Species in Edinburgh, 1804–1834, Edinburgh University Press, 222 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVII, no. 7 (23 April 2020), pp. 22–24. Quammen, quoted from p. 24 of his review.

Citations

- Freeman 2007, p. 76.

- "Fellows of the Royal Society". London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015.

- "Darwin Endless Forms » Darwin in Cambridge". Archived from the original on 23 March 2017.

- "Charles Darwin's personal finances revealed in new find". 22 March 2009. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- "Darwin" Archived 18 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine entry in Collins English Dictionary.

- Desmond, Moore & Browne 2004

- Coyne, Jerry A. (2009). Why Evolution is True. Viking. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-0-670-02053-9.

- Larson 2004, pp. 79–111

- "Special feature: Darwin 200". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- "Westminster Abbey » Charles Darwin". Westminster Abbey » Home. 2 January 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

Leff 2000, Darwin's Burial - Coyne, Jerry A. (2009). Why Evolution is True. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-19-923084-6.

In The Origin, Darwin provided an alternative hypothesis for the development, diversification, and design of life. Much of that book presents evidence that not only supports evolution but at the same time refutes creationism. In Darwin's day, the evidence for his theories was compelling but not completely decisive.

- Glass, Bentley (1959). Forerunners of Darwin. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. iv. ISBN 978-0-8018-0222-5.

Darwin's solution is a magnificent synthesis of evidence...a synthesis...compelling in honesty and comprehensiveness

- van Wyhe 2008

- Bowler 2003, pp. 178–179, 338, 347

- The Complete Works of Darwin Online – Biography. Archived 7 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine darwin-online.org.uk. Retrieved 2006-12-15

Dobzhansky 1973 - As Darwinian scholar Joseph Carroll of the University of Missouri–St. Louis puts it in his introduction to a modern reprint of Darwin's work: "The Origin of Species has special claims on our attention. It is one of the two or three most significant works of all time—one of those works that fundamentally and permanently alter our vision of the world...It is argued with a singularly rigorous consistency but it is also eloquent, imaginatively evocative, and rhetorically compelling." Carroll, Joseph, ed. (2003). On the origin of species by means of natural selection. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-55111-337-1.

- Leff 2000, About Charles Darwin

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 210, 284–285

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 263–274

- van Wyhe 2007, pp. 184, 187

- Beddall, B. G. (1968). "Wallace, Darwin, and the Theory of Natural Selection". Journal of the History of Biology. 1 (2): 261–323. doi:10.1007/BF00351923.

- Freeman 1977

- "AboutDarwin.com – All of Darwin's Books". www.aboutdarwin.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- Desmond, Adrian J. (13 September 2002). "Charles Darwin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- John H. Wahlert (11 June 2001). "The Mount House, Shrewsbury, England (Charles Darwin)". Darwin and Darwinism. Baruch College. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2008.

- Smith, Homer W. (1952). Man and His Gods. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. pp. 339–40.

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 12–15

Darwin 1958, pp. 21–25 - Darwin 1958, pp. 47–51

Desmond & Moore 2009, pp. 18–26 - Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 31–34.

- Browne 1995, pp. 72–88

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 42–43

- Browne 1995, pp. 47–48, 89–91

Desmond & Moore 2009, pp. 47–48 - Smith, Homer W. (1952). Man and His Gods. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. pp. 357–58.

- Darwin, Charles (1901). The life and letters of Charles Darwin. vol. 1. D. Appleton. pp. 43–44.

- Van Wyhe, John (ed.). "Darwin's insects in Stephens' Illustrations of British entomology (1829-32)". Darwin Online. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 73–79

Darwin 1958, pp. 57–67 - Browne 1995, p. 97

- von Sydow 2005, pp. 5–7

- Darwin 1958, pp. 67–68

- Browne 1995, pp. 128–129, 133–141

- "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 105 – Henslow, J. S. to Darwin, C. R., 24 Aug 1831". Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 94–97

- Browne 1995, pp. 204–210

- Keynes 2000, pp. ix–xi

- van Wyhe 2008b, pp. 18–21

- Gordon Chancellor; Randal Keynes (October 2006). "Darwin's field notes on the Galapagos: 'A little world within itself'". Darwin Online. Archived from the original on 1 September 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- Keynes 2001, pp. 21–22

- Browne 1995, pp. 183–190

- Keynes 2001, pp. 41–42

- Darwin 1958, pp. 73–74

- Browne 1995, pp. 223–235

Darwin 1835, p. 7

Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 210 - Keynes 2001, pp. 206–209

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 189–192, 198

- Eldredge 2006

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 131, 159

Herbert 1991, pp. 174–179 - "Darwin Online: 'Hurrah Chiloe': an introduction to the Port Desire Notebook". Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- Darwin 1845, pp. 205–208

- Browne 1995, pp. 243–244, 248–250, 382–383

- Keynes 2001, pp. 226–227

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 160–168, 182

Darwin 1887, p. 260 - Darwin 1958, pp. 98–99

- Keynes 2001, pp. 356–357

- Sulloway 1982, p. 19

- "Darwin Online: Coccatoos & Crows: An introduction to the Sydney Notebook". Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- Keynes 2001, pp. 398–399.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 301 – Darwin, C.R. to Darwin, C.S., 29 Apr 1836". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- Browne 1995, p. 336

- van Wyhe 2007, p. 197

- Keynes 2000, pp. xix–xx

Eldredge 2006 - Darwin 1859, p. 1

- Darwin 1835, editorial introduction

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 195–198

- Owen 1840, pp. 16, 73, 106

Eldredge 2006 - Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 201–205

Browne 1995, pp. 349–350 - Browne 1995, pp. 345–347

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 207–210

Sulloway 1982, pp. 20–23 - "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 346 – Darwin, C. R. to Darwin, C. S., 27 Feb 1837". Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2008. proposes a move on Friday 3 March 1837,

Darwin's Journal (Darwin 2006, pp. 12 verso) backdated from August 1838 gives a date of 6 March 1837 - Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 201, 212–221

- Sulloway 1982, pp. 9, 20–23

- Browne 1995, p. 360

"Darwin, C. R. (Read 14 March 1837) Notes on Rhea americana and Rhea darwinii, Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London". Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2008. - Herbert 1980, pp. 7–10

van Wyhe 2008b, p. 44

Darwin 1837, pp. 1–13, 26, 36, 74

Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 229–232 - UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Browne 1995, pp. 367–369

- Keynes 2001, p. xix

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 233–234

"Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 404 – Buckland, William to Geological Society of London, 9 Mar 1838". Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2008. - Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 233–236.

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 241–244, 426

- Browne 1995, p. xii

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 241–244

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 252, 476, 531

Darwin 1958, p. 115 - Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 254

Browne 1995, pp. 377–378

Darwin 1958, p. 84 - Darwin 1958, pp. 232–233

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 256–259

- "Darwin transmutation notebook D pp. 134e–135e". Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 264–265

Browne 1995, pp. 385–388

Darwin 1842, p. 7 - Darwin 1958, p. 120

- "Darwin transmutation notebook E p. 75". Archived from the original on 28 June 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- "Darwin transmutation notebook E p. 71". Archived from the original on 28 June 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project – Belief: historical essay". Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 272–279

- Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 279

- "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 419 – Darwin, C. R. to Fox, W. D., (15 June 1838)". Archived from the original on 4 September 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- van Wyhe 2007, pp. 186–192

- Darwin 1887, p. 32.

- Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 292

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 292–293

Darwin 1842, pp. xvi–xvii - Darwin 1958, p. 114

- van Wyhe 2007, pp. 183–184

- "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 729 – Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., (11 January 1844)". Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 734 – Hooker, J. D. to Darwin, C. R., 29 January 1844". Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- Darwin 1887, pp. 114–116

- van Wyhe 2007, p. 188

- Browne 1995, pp. 461–465

- "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 814 – Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., (7 Jan 1845)". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- van Wyhe 2007, pp. 190–191

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 320–323, 339–348

- "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 1236 – Darwin, C. R. to Hooker, J. D., 28 Mar 1849". Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- Browne 1995, pp. 498–501

- Darwin 1958, pp. 117–118

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 383–387

- Freeman 2007, pp. 107, 109

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 419–420

- Darwin Online: Photograph of Charles Darwin by Maull and Polyblank for the Literary and Scientific Portrait Club (1855) Archived 7 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, John van Wyhe, December 2006

- Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 412–441, 457–458, 462–463