Taiwan Strait

The Taiwan Strait, also known as the Formosa Strait, is a 180-kilometer (110 mi)-wide strait separating Taiwan and mainland China. The strait is currently part of the South China Sea and connects to the East China Sea to the north. The narrowest part is 130 km (81 mi) wide.[1]

| Taiwan Strait | |

|---|---|

Taiwan Strait  Taiwan Strait | |

A map showing the Taiwan Strait Area | |

| Coordinates | 24°48′40″N 119°55′42″E |

| Basin countries | Republic of China (Taiwan) People's Republic of China |

| Max. width | 130 km (81 mi) |

| Taiwan Strait | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣海峽 台灣海峽 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾海峡 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hokkien POJ | Tâi-ôan Hái-kiap | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taihai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺海 台海 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台海 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hokkien POJ | Tâi-hái | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Taiwan Sea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Black Ditch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 烏水溝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 乌水沟 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hokkien POJ | O͘ Chúi-kau | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Black Ditch | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Names

Former names of the Taiwan Strait include the Formosa Strait or Strait of Formosa, from a dated name for Taiwan; the Strait of Fokien or Fujian, from the Chinese province forming the strait's western shore;[2] and the Black Ditch, a calque of the strait's name in Hokkien and Hakka.

Geography

The Taiwan Strait is the body of water separating Fujian Province from Taiwan Island.

Current international agreement does not define the Taiwan Strait but places its waters within the South China Sea, whose northern limit runs from Cape Fugui (the northernmost point on Taiwan Island) to Niushan Island to the southernmost point of Pingtan Island and thence westward along the parallel 25° 24′ N. to the coast of Fujian Province.[3]

The still-unapproved draft for a new edition of the IHO's Limits of Oceans and Seas does precisely define the Taiwan Strait, classifying it as part of the North Pacific Ocean.[4] It makes the Taiwan Strait a body of water between the East and South China Seas and delimits it:[5]

On the North:

A line joining the coast of China (25° 42′ N - 119° 36′ E) eastward to Xiang Cape (25° 40′ N - 119° 47′ 10″ E), the northern extremity of Haitan Island, and thence to Fugui Cape (25° 17′ 45″ N - 121° 32′ 30″ E), the northern extremity of Taiwan Island (the common limit with the East China Sea, see 7.3).On the East:

From Fugui Cape southward, along the western coast of Taiwan Island, to Eluan Cape (21° 53′ 45″ N - 120° 51′ 30″ E), the southern extremity of this island.On the South:

A line joining Eluan Cape northwestward, along the southern banks of Nanao Island, to the southeastern extremity of this island (23° 23′ 35″ N - 117° 07′ 15″ E); thence westward, along the southern coast of Nanao Island, to Changshan Head (23° 25′ 50″ N - 116° 56′ 25″ E), the western extremity of this island; and thence a line joining Changshan Head westward to the mouth of the Hanjiang River (23° 27′ 30″ N - 116° 52′ E), on the coast of China (the common limit with the South China Sea, see 6.1).On the West:

From the mouth of Hanjiang River northeastward, along the coast of China, to position 25° 42′ N - 119° 36′ E.

Both the People's Republic of China (PRC) on the mainland and the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan Island espouse a One-China Policy that considers the strait part of the exclusive economic zone of a single "China". In practice, a maritime border of control exists, known as the Cross-Strait Median (t 海峽中線, s 海峡中线, Hǎixiá Zhōngxiàn).[6]

The entire strait is on Asia's continental shelf. It is almost entirely less than 150 m (490 ft) deep, with a short ravine of that depth off the south-west coast of Taiwan. As such, there are many islands in the strait. The largest and most important islands off the Fujianese coast are Xiamen, Gulangyu, Pingtan (the "Haitan" of the IHO delineation), Kinmen, and Matsu. The first three are controlled by the PRC; the last two by the ROC. Within the strait lie the Penghu or Pescadores, also controlled by the ROC. There is a major underwater bank 40–60 km (25–37 mi) north of the Penghu Islands.[7]

All of Fujian Province's rivers except the Ting run into the Taiwan Strait. The largest two are the Min and the Jiulong.

Geology

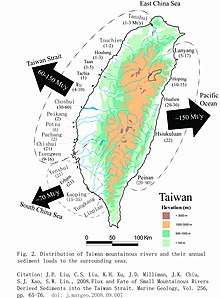

Sediment distribution

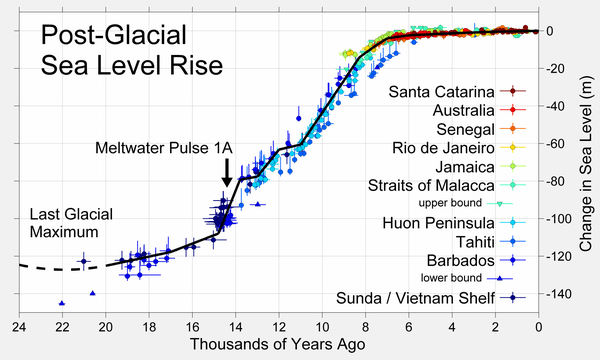

Every year Taiwan rivers deliver up to 370 million tons sediments to the sea, among them, there are 60-150 million tons are delivered into the Taiwan Strait[8]. During the past 10 kyr, there has been 600 billion tons riverine sediments deposited in the Taiwan Strait, forming locally an up-to 40-m thick lobe in the southern part of the Taiwan Strait[9]. see the Holocence mud distribution map.

History

The Strait mostly separated the Han culture of the Chinese mainland from Taiwan Island's aborigines for millennia, although the Hakka and Hoklo traded and migrated across it. A Fujianese shamaness named Lin Mo is said to have drowned in the strait while rescuing members of her family in the 10th century; by the 12th century, her story had given rise to the cult of "Mazu" still celebrated on both sides of the strait.

Early modern Taiwan was a haven by Chinese and Japanese pirates. European explorers, principally the Spanish and Dutch, also took advantage of the strait to establish forward bases for trade with the mainland during the Ming; the bases were also used for raiding both the Chinese coast and the trading ships of rival countries.

Widespread Chinese migration across the strait began in the late Ming. During the Qing conquest, Ming refugees fled to Taiwan. Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga) expelled the Dutch and established the Kingdom of Tungning in 1661, planning to launch a reconquest of the mainland in the name of the Southern Ming branches of the old imperial dynasty. Dorgon and the Kangxi Emperor were able to consolidate their control over southern mainland China; Koxinga found himself limited to raiding across the strait. His grandson Zheng Keshuang surrendered to the Qing after his admiral lost the 1683 Battle of the Penghu Islands in the middle of the strait.

The Manchu-led Qing Empire faced constant revolts among the Han, Hoklo, and Hakka on Taiwan over the next 200 years. They never exerted much control over the aboriginal tribes on the eastern half of the island, prompting international incidents and American and Japanese invasions when the natives massacred the survivors of shipwrecks.

Japan seized the Penghu Islands during the First Sino-Japanese War and gained control of Taiwan at its conclusion in 1895. Control of the eastern half of the strait was used to establish control of the southern Chinese coast during the Second World War. The strait protected Japanese bases and industry on Taiwan from Chinese attack and sabotage, but aerial warfare reached the island by 1943. The 1944 Taiwan Air Battle gave the United States Pacific Fleet air supremacy from its carrier groups and Philippine bases; subsequently, bombing was continuous until Japan's surrender in 1945.

During and after the Chinese Civil War, uprisings and peaceful dissent against the Nationalist government of the Republic of China were met with martial law and brutal repression now known as the "White Terror". The rapid advance of the Communist PLA in 1949 provoked the government's panicked retreat across the Taiwan Strait. The PLA's successful amphibious conquest of Hainan Island in 1950 suggested Taiwan would soon fall as well but the PRC's entrance into the Korean War in the autumn of that year provoked the United States into resuming its support of the Nationalists.

The US Seventh Fleet patrolled the strait both to protect the island from Communist assault and to prevent the Taiwanese from beginning international incidents through assaults on the mainland expected to be fruitless. Chinese assaults led to "Taiwan Strait Crises" in 1954 & 1955 and 1958 that were ended by threat of war with the US; Chiang Kai-shek's plans for China's reconquest were mostly abandoned after a failed landing at Magong in 1965. Hopes for immediate military reunification of China gave way to a One-China Policy espoused by both Chinas and the international community; most international recognition switched from the Republic of China to the People's Republic of China in the 1970s. A third Taiwan Strait Crisis occurred in 1995 & 1996 and cross-Strait relations remain strained, with a strengthening PRC economy also strengthening its military and deployments on the straits.

Economy

Fishermen have used the strait as a fishing resource since time immemorial. In the modern world, it hosts major shipping lanes.

As part of the People's Republic of China's National Expressway Plan, a tunnel, or possibly a bridge, was proposed in 2005 to link the city of Fuzhou with Taipei across the strait.[10] If such an extreme construction were ever built, it would by far exceed the length of any man-made tunnel in the world today. Engineers in Beijing state that a tunnel is technically feasible. However, the Republic of China government in Taiwan has refused to open direct links out of concern for Taiwan's security and in fear that by doing so it would have to recognize the People's Republic of China's one-China policy, since China split into two in the Chinese Civil War and they still have an adversarial relationship.[11][12]

Gallery

Looking south from the East to South China Sea

Looking south from the East to South China Sea Looking north from the South to East China Sea

Looking north from the South to East China Sea

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taiwan Strait. |

- 1st, 2nd, & 3rd Taiwan Strait Crisis

- Battle of Guningtou

- China Airlines Flight 611

- Cross-Strait relations

- List of Pacific typhoon seasons

- Luzon Strait

- Taijiang National Park

- Western Taiwan Straits Economic Zone

References

Citations

- "Geography". Government Information Office. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- EB (1879), p. 415.

- IHO (1953), §49.

- IHO (1986), Ch. 7.

- IHO (1986), Ch. 7.2.

- 大公報文章:"海峽中線"應該廢除, chinareviewnews.com. (in Chinese)

- Sea depth map.

- "Liu, J., Liu, C., Xu, K., Milliman, J., Chiu, J., Kao, S., Lin, S., 2008. Flux and fate of small mountainous rivers derived sediments into the Taiwan Strait. Mar. Geol. 256, 65-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2008.09.007". 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); External link in|title=(help) - "Liu, J., Liu, C., Xu, K., Milliman, J., Chiu, J., Kao, S., Lin, S., 2008. Flux and fate of small mountainous rivers derived sediments into the Taiwan Strait. Mar. Geol. 256, 65-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2008.09.007". 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); External link in|title=(help) - China, China (1 December 2008). "Medium to Long Term Rail Network Plan for PRC". China Rail Department. China. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- Wu, Zhong (14 January 2005). "Mainland to triple highway network". The Standard. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- Gittings, John (8 April 2002). "Plans unveiled in China for Taiwan tunnel". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

Bibliography

- , Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th ed., Vol. IX, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1879, pp. 415–17.

- S-23: Limits of Oceans and Seas (PDF) (3rd ed.), Monaco: International Hydrographic Organization, 1953.

- S-23: Limits of Oceans and Seas (4th (draft) ed.), Monaco: International Hydrographic Organization, 1986.