Opium

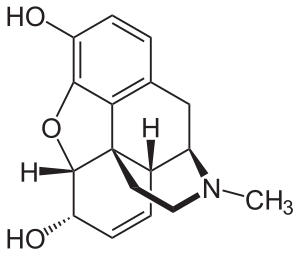

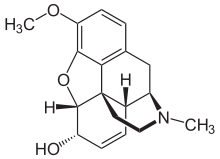

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: Lachryma papaveris) is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy Papaver somniferum.[5] Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which is processed chemically to produce heroin and other synthetic opioids for medicinal use and for illegal drug trade. The latex also contains the closely related opiates codeine and thebaine, and non-analgesic alkaloids such as papaverine and noscapine. The traditional, labor-intensive method of obtaining the latex is to scratch ("score") the immature seed pods (fruits) by hand; the latex leaks out and dries to a sticky yellowish residue that is later scraped off and dehydrated. The word "meconium" (derived from the Greek for "opium-like", but now used to refer to newborn stools) historically referred to related, weaker preparations made from other parts of the opium poppy or different species of poppies.[6]

| Opium | |

|---|---|

Opium poppy seed pod exuding latex from a cut | |

| Product name | Opium |

| Source plant(s) | Papaver somniferum |

| Part(s) of plant | Latex |

| Geographic origin | Uncertain, possibly Asia Minor,[1] or Spain, southern France and northwestern Africa[2] |

| Active ingredients | |

| Main producers | |

| Main consumers | Worldwide (#1: Europe)[3] |

| Wholesale price | US$3,000 per kilogram (as of 2002)[4] |

| Retail price | US$16,000 per kilogram (as of 2002)[4] |

| Legal status |

|

The production methods have not changed since ancient times. Through selective breeding of the Papaver somniferum plant, the content of the phenanthrene alkaloids morphine, codeine, and to a lesser extent thebaine has been greatly increased. In modern times, much of the thebaine, which often serves as the raw material for the synthesis for oxycodone, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, and other semisynthetic opiates, originates from extracting Papaver orientale or Papaver bracteatum.

For the illegal drug trade, the morphine is extracted from the opium latex, reducing the bulk weight by 88%. It is then converted to heroin which is almost twice as potent,[7] and increases the value by a similar factor. The reduced weight and bulk make it easier to smuggle.[8]

History

The Mediterranean region contains the earliest archeological evidence of human use; the oldest known seeds date back to more than 5000 BCE in the Neolithic age[9] with purposes such as food, anaesthetics, and ritual. Evidence from ancient Greece indicates that opium was consumed in several ways, including inhalation of vapors, suppositories, medical poultices, and as a combination with hemlock for suicide.[10] The Sumerian, Assyrian, Egyptian, Indian, Minoan, Greek, Roman, Persian and Arab Empires all made widespread use of opium, which was the most potent form of pain relief then available, allowing ancient surgeons to perform prolonged surgical procedures. Opium is mentioned in the most important medical texts of the ancient world, including the Ebers Papyrus and the writings of Dioscorides, Galen, and Avicenna. Widespread medical use of unprocessed opium continued through the American Civil War before giving way to morphine and its successors, which could be injected at a precisely controlled dosage.

Ancient use (pre-500 CE)

Opium has been actively collected since approximately 3400 BCE.[11] The upper Asian belt of Afghanistan, Pakistan, northern India, and Burma still account for the world's largest supply of opium.

At least 17 finds of Papaver somniferum from Neolithic settlements have been reported throughout Switzerland, Germany, and Spain, including the placement of large numbers of poppy seed capsules at a burial site (the Cueva de los Murciélagos, or "Bat Cave", in Spain), which have been carbon-14 dated to 4200 BCE. Numerous finds of P. somniferum or P. setigerum from Bronze Age and Iron Age settlements have also been reported.[12] The first known cultivation of opium poppies was in Mesopotamia, approximately 3400 BCE, by Sumerians, who called the plant hul gil, the "joy plant".[13][14] Tablets found at Nippur, a Sumerian spiritual center south of Baghdad, described the collection of poppy juice in the morning and its use in production of opium.[1] Cultivation continued in the Middle East by the Assyrians, who also collected poppy juice in the morning after scoring the pods with an iron scoop; they called the juice aratpa-pal, possibly the root of Papaver. Opium production continued under the Babylonians and Egyptians.

Opium was used with poison hemlock to put people quickly and painlessly to death, but it was also used in medicine. Spongia somnifera, sponges soaked in opium, were used during surgery.[13] The Egyptians cultivated opium thebaicum in famous poppy fields around 1300 BCE. Opium was traded from Egypt by the Phoenicians and Minoans to destinations around the Mediterranean Sea, including Greece, Carthage, and Europe. By 1100 BCE, opium was cultivated on Cyprus, where surgical-quality knives were used to score the poppy pods, and opium was cultivated, traded, and smoked.[15] Opium was also mentioned after the Persian conquest of Assyria and Babylonian lands in the 6th century BCE.[1]

From the earliest finds, opium has appeared to have ritual significance, and anthropologists have speculated ancient priests may have used the drug as a proof of healing power.[13] In Egypt, the use of opium was generally restricted to priests, magicians, and warriors, its invention is credited to Thoth, and it was said to have been given by Isis to Ra as treatment for a headache.[1] A figure of the Minoan "goddess of the narcotics", wearing a crown of three opium poppies, c. 1300 BCE, was recovered from the Sanctuary of Gazi, Crete, together with a simple smoking apparatus.[15][16] The Greek gods Hypnos (Sleep), Nyx (Night), and Thanatos (Death) were depicted wreathed in poppies or holding them. Poppies also frequently adorned statues of Apollo, Asklepios, Pluto, Demeter, Aphrodite, Kybele and Isis, symbolizing nocturnal oblivion.[1]

Islamic societies (500–1500 CE)

As the power of the Roman Empire declined, the lands to the south and east of the Mediterranean Sea became incorporated into the Islamic Empires. Some Muslims believe hadiths, such as in Sahih Bukhari, prohibits every intoxicating substance, though the use of intoxicants in medicine has been widely permitted by scholars.[17] Dioscorides' five-volume De Materia Medica, the precursor of pharmacopoeias, remained in use (which was edited and improved in the Arabic versions[18]) from the 1st to 16th centuries, and described opium and the wide range of its uses prevalent in the ancient world.[19]

Between 400 and 1200 CE, Arab traders introduced opium to China, and to India by 700.[20][1][14][21] The physician Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi of Persian origin ("Rhazes", 845–930 CE) maintained a laboratory and school in Baghdad, and was a student and critic of Galen; he made use of opium in anesthesia and recommended its use for the treatment of melancholy in Fi ma-la-yahdara al-tabib, "In the Absence of a Physician", a home medical manual directed toward ordinary citizens for self-treatment if a doctor was not available.[22][23]

The renowned Andalusian ophthalmologic surgeon Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi ("Abulcasis", 936–1013 CE) relied on opium and mandrake as surgical anaesthetics and wrote a treatise, al-Tasrif, that influenced medical thought well into the 16th century.[24]

The Persian physician Abū ‘Alī al-Husayn ibn Sina ("Avicenna") described opium as the most powerful of the stupefacients, in comparison to mandrake and other highly effective herbs, in The Canon of Medicine. The text lists medicinal effects of opium, such as analgesia, hypnosis, antitussive effects, gastrointestinal effects, cognitive effects, respiratory depression, neuromuscular disturbances, and sexual dysfunction. It also refers to opium's potential as a poison. Avicenna describes several methods of delivery and recommendations for doses of the drug.[25] This classic text was translated into Latin in 1175 and later into many other languages and remained authoritative until the 19th century.[26] Şerafeddin Sabuncuoğlu used opium in the 14th-century Ottoman Empire to treat migraine headaches, sciatica, and other painful ailments.[27]

Reintroduction to Western medicine

Manuscripts of Pseudo-Apuleius's 5th-century work from the 10th and 11th centuries refer to the use of wild poppy Papaver agreste or Papaver rhoeas (identified as P. silvaticum) instead of P. somniferum for inducing sleep and relieving pain.[28]

The use of Paracelsus' laudanum was introduced to Western medicine in 1527, when Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, better known by the name Paracelsus, returned from his wanderings in Arabia with a famous sword, within the pommel of which he kept "Stones of Immortality" compounded from opium thebaicum, citrus juice, and "quintessence of gold".[14][29][30] The name "Paracelsus" was a pseudonym signifying him the equal or better of Aulus Cornelius Celsus, whose text, which described the use of opium or a similar preparation, had recently been translated and reintroduced to medieval Europe.[31] The Canon of Medicine, the standard medical textbook Paracelsus burned in a public bonfire three weeks after being appointed professor at the University of Basel, also described the use of opium, though many Latin translations were of poor quality.[29] Laudanum ("worthy of praise") was originally the 16th-century term for a medicine associated with a particular physician that was widely well-regarded, but became standardized as "tincture of opium", a solution of opium in ethanol, which Paracelsus has been credited with developing.[20] During his lifetime, Paracelsus was viewed as an adventurer who challenged the theories and mercenary motives of contemporary medicine with dangerous chemical therapies, but his therapies marked a turning point in Western medicine. In the 1660s, laudanum was recommended for pain, sleeplessness, and diarrhea by Thomas Sydenham,[32] the renowned "father of English medicine" or "English Hippocrates", to whom is attributed the quote, "Among the remedies which it has pleased Almighty God to give to man to relieve his sufferings, none is so universal and so efficacious as opium."[33] Use of opium as a cure-all was reflected in the formulation of mithridatium described in the 1728 Chambers Cyclopedia, which included true opium in the mixture. Subsequently, laudanum became the basis of many popular patent medicines of the 19th century.

Compared to other chemicals available to 18th century regular physicians, opium was a benign alternative to the arsenics, mercuries, or emetics, and it was remarkably successful in alleviating a wide range of ailments. Due to the constipation often produced by the consumption of opium, it was one of the most effective treatments for cholera, dysentery, and diarrhea. As a cough suppressant, opium was used to treat bronchitis, tuberculosis, and other respiratory illnesses. Opium was additionally prescribed for rheumatism and insomnia.[34] Medical textbooks even recommended its use by people in good health, to "optimize the internal equilibrium of the human body".[20]

During the 18th century, opium was found to be a good remedy for nervous disorders. Due to its sedative and tranquilizing properties, it was used to quiet the minds of those with psychosis, help with people who were considered insane, and also to help treat patients with insomnia.[35] However, despite its medicinal values in these cases, it was noted that in cases of psychosis, it could cause anger or depression, and due to the drug's euphoric effects, it could cause depressed patients to become more depressed after the effects wore off because they would get used to being high.[35]

The standard medical use of opium persisted well into the 19th century. US president William Henry Harrison was treated with opium in 1841, and in the American Civil War, the Union Army used 175,000 lb (80,000 kg) of opium tincture and powder and about 500,000 opium pills.[1] During this time of popularity, users called opium "God's Own Medicine".[36]

One reason for the increase in opiate consumption in the United States during the 19th century was the prescribing and dispensing of legal opiates by physicians and pharmacists to women with "female complaints" (mostly to relieve menstrual pain and hysteria).[34] Because opiates were viewed as more humane than punishment or restraint, they were often used to treat the mentally ill. Between 150,000 and 200,000 opiate addicts lived in the United States in the late 19th century and between two-thirds and three-quarters of these addicts were women.[37]

Opium addiction in the later 19th century received a hereditary definition. Dr. George Beard in 1869 proposed his theory of neurasthenia, a hereditary nervous system deficiency that could predispose an individual to addiction. Neurasthenia was increasingly tied in medical rhetoric to the "nervous exhaustion" suffered by many a white-collar worker in the increasingly hectic and industrialized U.S. life—the most likely potential clients of physicians.

Recreational use in Europe, the Middle East and the US (11th to 19th centuries)

.jpg)

Soldiers returning home from the Crusades in the 11th to 13th century brought opium with them.[20] Opium is said to have been used for recreational purposes from the 14th century onwards in Muslim societies. Ottoman and European testimonies confirm that from the 16th to the 19th centuries Anatolian opium was eaten in Constantinople as much as it was exported to Europe.[38] In 1573, for instance, a Venetian visitor to the Ottoman Empire observed many of the Turkish natives of Constantinople regularly drank a "certain black water made with opium" that makes them feel good, but to which they become so addicted, if they try to go without, they will "quickly die".[39] From drinking it, dervishes claimed the drugs bestowed them with visionary glimpses of future happiness.[40] Indeed, the Ottoman Empire supplied the West with opium long before China and India.[41]

England

In England, opium fulfilled a "critical" role, as it did other societies, in addressing multifactorial pain, cough, dysentery, diarrhea, as argued by Virginia Berridge.[42] A medical panacea of the 19th century, "any respectable person" could purchase a range of hashish pastes and (later) morphine with complementary injection kit.[42]

Thomas De Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1822), one of the first and most famous literary accounts of opium addiction written from the point of view of an addict details the pleasures and dangers of the drug. In the book, it is not Ottoman, nor Chinese, addicts about whom he writes, but English opium users: "I question whether any Turk, of all that ever entered the paradise of opium-eaters, can have had half the pleasure I had."[43] De Quincey writes about the great English Romantic poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834), whose "Kubla Khan" is also widely considered to be a poem of the opium experience. Coleridge began using opium in 1791 after developing jaundice and rheumatic fever, and became a full addict after a severe attack of the disease in 1801, requiring 80–100 drops of laudanum daily.[44]

Extensive textual and pictorial sources also show that poppy cultivation and opium consumption were widespread in Safavid Iran[45] and Mughal India.[46]

China

Recreational use in China

The earliest clear description of the use of opium as a recreational drug in China came from Xu Boling, who wrote in 1483 that opium was "mainly used to aid masculinity, strengthen sperm and regain vigor", and that it "enhances the art of alchemists, sex and court ladies". He also described an expedition sent by the Ming dynasty Chenghua Emperor in 1483 to procure opium for a price "equal to that of gold" in Hainan, Fujian, Zhejiang, Sichuan and Shaanxi, where it is close to the western lands of Xiyu. A century later, Li Shizhen listed standard medical uses of opium in his renowned Compendium of Materia Medica (1578), but also wrote that "lay people use it for the art of sex," in particular the ability to "arrest seminal emission". This association of opium with sex continued in China until the end of the 19th century.

Opium smoking began as a privilege of the elite and remained a great luxury into the early 19th century. However, by 1861, Wang Tao wrote that opium was used even by rich peasants, and even a small village without a rice store would have a shop where opium was sold.[47]

It is important to note that "recreational use" of opium was part of a civilized and mannered ritual prior to the extensive prohibitions that came later.[48] In places of gathering, often tea shops, or a person's home servings of opium were offered as a form of greeting and politeness. often served with tea (in China) and with specific and fine utensils and beautifully carved wooden pipes. The wealthier the smoker, the finer and more expensive material used in ceremony.[48] The image of seedy underground, destitute smokers were often generated by anti-opium narratives and became a more accurate image of opium use following the effects of large scale opium prohibition in the 1880s.[48][49]

Prohibitions in China

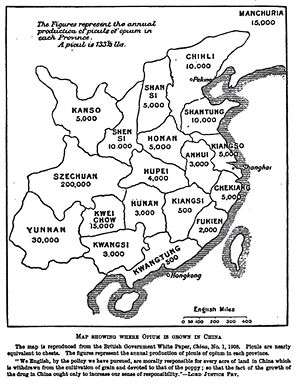

Opium prohibition in China began in 1729, yet was followed by nearly two centuries of increasing opium use. A massive destruction of opium by an emissary of the Chinese Daoguang Emperor in an attempt to stop opium smuggling led to the First Opium War (1839–1842), in which Britain defeated China. After 1860, opium use continued to increase with widespread domestic production in China. By 1905, an estimated 25 percent of the male population were regular consumers of the drug. Recreational use of opium elsewhere in the world remained rare into late in the 19th century, as indicated by ambivalent reports of opium usage.[48] In 1906, 41,000 tons were produced, but because 39,000 tons of that year's opium were consumed in China, overall usage in the rest of the world was much lower.[50] These figures from 1906 have been criticized as overestimates.[51]

Smoking of opium came on the heels of tobacco smoking and may have been encouraged by a brief ban on the smoking of tobacco by the Ming emperor. The prohibition ended in 1644 with the coming of the Qing dynasty, which encouraged smokers to mix in increasing amounts of opium.[1] In 1705, Wang Shizhen wrote, "nowadays, from nobility and gentlemen down to slaves and women, all are addicted to tobacco." Tobacco in that time was frequently mixed with other herbs (this continues with clove cigarettes to the modern day), and opium was one component in the mixture. Tobacco mixed with opium was called madak (or madat) and became popular throughout China and its seafaring trade partners (such as Taiwan, Java, and the Philippines) in the 17th century.[47] In 1712, Engelbert Kaempfer described addiction to madak: "No commodity throughout the Indies is retailed with greater profit by the Batavians than opium, which [its] users cannot do without, nor can they come by it except it be brought by the ships of the Batavians from Bengal and Coromandel."[21]

Fueled in part by the 1729 ban on madak, which at first effectively exempted pure opium as a potentially medicinal product, the smoking of pure opium became more popular in the 18th century. In 1736, the smoking of pure opium was described by Huang Shujing, involving a pipe made from bamboo rimmed with silver, stuffed with palm slices and hair, fed by a clay bowl in which a globule of molten opium was held over the flame of an oil lamp. This elaborate procedure, requiring the maintenance of pots of opium at just the right temperature for a globule to be scooped up with a needle-like skewer for smoking, formed the basis of a craft of "paste-scooping" by which servant girls could become prostitutes as the opportunity arose.[47]

Chinese diaspora

The Chinese Diaspora (1800s to 1949) first began during the 19th century due to famine and political upheaval, as well as rumors of wealth to be had outside of Southeast Asia. Chinese emigrants to cities such as San Francisco, London, and New York brought with them the Chinese manner of opium smoking, and the social traditions of the opium den.[52][53] The Indian Diaspora distributed opium-eaters in the same way, and both social groups survived as "lascars" (seamen) and "coolies" (manual laborers). French sailors provided another major group of opium smokers, having gotten the habit while in French Indochina, where the drug was promoted and monopolized by the colonial government as a source of revenue.[54][55] Among white Europeans, opium was more frequently consumed as laudanum or in patent medicines. Britain's All-India Opium Act of 1878 formalized ethnic restrictions on the use of opium, limiting recreational opium sales to registered Indian opium-eaters and Chinese opium-smokers only and prohibiting its sale to workers from Burma.[56] Likewise, in San Francisco, Chinese immigrants were permitted to smoke opium, so long as they refrained from doing so in the presence of whites.[52]

Because of the low social status of immigrant workers, contemporary writers and media had little trouble portraying opium dens as seats of vice, white slavery, gambling, knife- and revolver-fights, and a source for drugs causing deadly overdoses, with the potential to addict and corrupt the white population. By 1919, anti-Chinese riots attacked Limehouse, the Chinatown of London. Chinese men were deported for playing keno and sentenced to hard labor for opium possession. Due to this, both the immigrant population and the social use of opium fell into decline.[57][58] Yet despite lurid literary accounts to the contrary, 19th-century London was not a hotbed of opium smoking. The total lack of photographic evidence of opium smoking in Britain, as opposed to the relative abundance of historical photos depicting opium smoking in North America and France, indicates the infamous Limehouse opium-smoking scene was little more than fantasy on the part of British writers of the day, who were intent on scandalizing their readers while drumming up the threat of the "yellow peril".[59][60]

Prohibition and conflict in China

A large scale opium prohibition attempt began in 1729, when the Qing Yongzheng Emperor, disturbed by madak smoking at court and carrying out the government's role of upholding Confucian virtues, officially prohibited the sale of opium, except for a small amount for medicinal purposes. The ban punished sellers and opium den keepers, but not users of the drug.[21] Opium was banned completely in 1799, and this prohibition continued until 1860.[61]

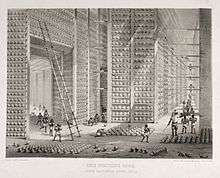

During the Qing dynasty, China opened itself to foreign trade under the Canton System through the port of Guangzhou (Canton), with traders from the East India Company visiting the port by the 1690s. Due to the growing British demand for Chinese tea and the Chinese Emperor's lack of interest in British commodities other than silver, British traders resorted to trade in opium as a high-value commodity for which China was not self-sufficient. The English traders had been purchasing small amounts of opium from India for trade since Ralph Fitch first visited in the mid-16th century.[21] Trade in opium was standardized, with production of balls of raw opium, 1.1–1.6 kg (2.4–3.5 lb), 30% water content, wrapped in poppy leaves and petals, and shipped in chests of 60–65 kg (132–143 lb) (one picul).[21] Chests of opium were sold in auctions in Calcutta with the understanding that the independent purchasers would then smuggle it into China.

China had a positive balance sheet in trading with the British, which led to a decrease of the British silver stocks. Therefore, the British tried to encourage Chinese opium use to enhance their balance, and they delivered it from Indian provinces under British control. In India, its cultivation, as well as the manufacture and traffic to China, were subject to the British East India Company (BEIC), as a strict monopoly of the British government.[62] Indian farmers were forced by the British East India company to grow poppy against their wishes, often using a combination of strong arm tactics and debt.[63] There was an extensive and complicated system of BEIC agencies involved in the supervision and management of opium production and distribution in India.

After the 1757 Battle of Plassey and 1764 Battle of Buxar, the British East India Company gained the power to act as diwan of Bengal, Bihar, and Odisha (See company rule in India). This allowed the company to exercise a monopoly over opium production and export in India, to encourage ryots to cultivate the cash crops of indigo and opium with cash advances, and to prohibit the "hoarding" of rice. This strategy led to the increase of the land tax to 50 percent of the value of crops and to the doubling of East India Company profits by 1777. It is also claimed to have contributed to the starvation of 10 million people in the Bengal famine of 1770. Beginning in 1773, the British government began enacting oversight of the company's operations, and in response to the Indian Rebellion of 1857, this policy culminated in the establishment of direct rule over the presidencies and provinces of British India. Bengal opium was highly prized, commanding twice the price of the domestic Chinese product, which was regarded as inferior in quality.[50]

Some competition came from the newly independent United States, which began to compete in Guangzhou, selling Turkish opium in the 1820s. Portuguese traders also brought opium from the independent Malwa states of western India, although by 1820, the British were able to restrict this trade by charging "pass duty" on the opium when it was forced to pass through Bombay to reach an entrepot.[21] Despite drastic penalties and continued prohibition of opium until 1860, opium smuggling rose steadily from 200 chests per year under the Yongzheng Emperor to 1,000 under the Qianlong Emperor, 4,000 under the Jiaqing Emperor, and 30,000 under the Daoguang Emperor.[64] The illegal sale of opium became one of the world's most valuable single commodity trades and has been called "the most long continued and systematic international crime of modern times".[65] Opium smuggling provided 15 to 20 percent of the British Empire's revenue and simultaneously caused scarcity of silver in China.[66]

In response to the ever-growing number of Chinese people becoming addicted to opium, the Qing Daoguang Emperor took strong action to halt the smuggling of opium, including the seizure of cargo. In 1838, the Chinese Commissioner Lin Zexu destroyed 20,000 chests of opium in Guangzhou.[21] Given that a chest of opium was worth nearly US$1,000 in 1800, this was a substantial economic loss. The British queen Victoria, not willing to replace the cheap opium with costly silver, began the First Opium War in 1840, the British winning Hong Kong and trade concessions in the first of a series of Unequal Treaties.

The opium trade incurred intense enmity from the later British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone.[67] As a member of Parliament, Gladstone called it "most infamous and atrocious" referring to the opium trade between China and British India in particular.[68] Gladstone was fiercely against both of the Opium Wars Britain waged in China in the First Opium War initiated in 1840 and the Second Opium War initiated in 1857, denounced British violence against Chinese, and was ardently opposed to the British trade in opium to China.[69] Gladstone lambasted it as "Palmerston's Opium War" and said that he felt "in dread of the judgments of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China" in May 1840.[70] A famous speech was made by Gladstone in Parliament against the First Opium War.[71][72] Gladstone criticized it as "a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to cover this country with permanent disgrace".[73] His hostility to opium stemmed from the effects of opium brought upon his sister Helen.[74] Due to the First Opium war brought on by Palmerston, there was initial reluctance to join the government of Peel on part of Gladstone before 1841.[75]

Following China's defeat in the Second Opium War in 1858, China was forced to legalize opium and began massive domestic production. Importation of opium peaked in 1879 at 6,700 tons, and by 1906, China was producing 85 percent of the world's opium, some 35,000 tons, and 27 percent of its adult male population regularly used opium—13.5 million people consuming 39,000 tons of opium yearly.[50] From 1880 to the beginning of the Communist era, the British attempted to discourage the use of opium in China, but this effectively promoted the use of morphine, heroin, and cocaine, further exacerbating the problem of addiction.[49]

.jpg)

Scientific evidence of the pernicious nature of opium use was largely undocumented in the 1890s, when Protestant missionaries in China decided to strengthen their opposition to the trade by compiling data which would demonstrate the harm the drug did. Faced with the problem that many Chinese associated Christianity with opium, partly due to the arrival of early Protestant missionaries on opium clippers, at the 1890 Shanghai Missionary Conference, they agreed to establish the Permanent Committee for the Promotion of Anti-Opium Societies in an attempt to overcome this problem and to arouse public opinion against the opium trade. The members of the committee were John Glasgow Kerr, MD, American Presbyterian Mission in Canton; B.C. Atterbury, MD, American Presbyterian Mission in Peking; Archdeacon Arthur E. Moule, Church Missionary Society in Shanghai; Henry Whitney, MD, American Board of Commissioners for foreign Missions in Foochow; the Rev. Samuel Clarke, China Inland Mission in Kweiyang; the Rev. Arthur Gostick Shorrock, English Baptist Mission in Taiyuan; and the Rev. Griffith John, London Mission Society in Hankow.[76] These missionaries were generally outraged over the British government's Royal Commission on Opium visiting India but not China. Accordingly, the missionaries first organized the Anti-Opium League in China among their colleagues in every mission station in China. American missionary Hampden Coit DuBose acted as first president. This organization, which had elected national officers and held an annual national meeting, was instrumental in gathering data from every Western-trained medical doctor in China, which was then published as William Hector Park compiled Opinions of Over 100 Physicians on the Use of Opium in China (Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission Press, 1899). The vast majority of these medical doctors were missionaries; the survey also included doctors who were in private practices, particularly in Shanghai and Hong Kong, as well as Chinese who had been trained in medical schools in Western countries. In England, the home director of the China Inland Mission, Benjamin Broomhall, was an active opponent of the opium trade, writing two books to promote the banning of opium smoking: The Truth about Opium Smoking and The Chinese Opium Smoker. In 1888, Broomhall formed and became secretary of the Christian Union for the Severance of the British Empire with the Opium Traffic and editor of its periodical, National Righteousness. He lobbied the British Parliament to stop the opium trade. He and James Laidlaw Maxwell appealed to the London Missionary Conference of 1888 and the Edinburgh Missionary Conference of 1910 to condemn the continuation of the trade. When Broomhall was dying, his son Marshall read to him from The Times the welcome news that an agreement had been signed ensuring the end of the opium trade within two years.

Official Chinese resistance to opium was renewed on September 20, 1906, with an antiopium initiative intended to eliminate the drug problem within 10 years. The program relied on the turning of public sentiment against opium, with mass meetings at which opium paraphernalia were publicly burned, as well as coercive legal action and the granting of police powers to organizations such as the Fujian Anti-Opium Society. Smokers were required to register for licenses for gradually reducing rations of the drug. Action against opium farmers centred upon a highly repressive incarnation of law enforcement in which rural populations had their property destroyed, their land confiscated and/or were publicly tortured, humiliated and executed.[77] Addicts sometimes turned to missionaries for treatment for their addiction, though many associated these foreigners with the drug trade. The program was counted as a substantial success, with a cessation of direct British opium exports to China (but not Hong Kong)[78] and most provinces declared free of opium production. Nonetheless, the success of the program was only temporary, with opium use rapidly increasing during the disorder following the death of Yuan Shikai in 1916.[79] Opium farming also increased, peaking in 1930 when the League of Nations singled China out as the primary source of illicit opium in East and Southeast Asia. Many[80] local powerholders facilitated the trade during this period to finance conflicts over territory and political campaigns. In some areas food crops were eradicated to make way for opium, contributing to famines in Kweichow and Shensi Provinces between 1921 and 1923, and food deficits in other provinces.

Beginning in 1915, Chinese nationalist groups came to describe the period of military losses and Unequal Treaties as the "Century of National Humiliation", later defined to end with the conclusion of the Chinese Civil War in 1949.[81]

In the northern provinces of Ningxia and Suiyuan in China, Chinese Muslim General Ma Fuxiang both prohibited and engaged in the opium trade. It was hoped that Ma Fuxiang would have improved the situation, since Chinese Muslims were well known for opposition to smoking opium.[82] Ma Fuxiang officially prohibited opium and made it illegal in Ningxia, but the Guominjun reversed his policy; by 1933, people from every level of society were abusing the drug, and Ningxia was left in destitution.[83] In 1923, an officer of the Bank of China from Baotou found out that Ma Fuxiang was assisting the drug trade in opium which helped finance his military expenses. He earned US$2 million from taxing those sales in 1923. General Ma had been using the bank, a branch of the Government of China's exchequer, to arrange for silver currency to be transported to Baotou to use it to sponsor the trade.[84]

The opium trade under the Chinese Communist Party was important to its finances in the 1940s.[85] Peter Vladimirov's diary provided a first hand account.[86] Chen Yung-fa provided a detailed historical account of how the opium trade was essential to the economy of Yan'an during this period.[87] Mitsubishi and Mitsui were involved in the opium trade during the Japanese occupation of China.[88]

The Mao Zedong government is generally credited with eradicating both consumption and production of opium during the 1950s using unrestrained repression and social reform.[89][90] Ten million addicts were forced into compulsory treatment, dealers were executed, and opium-producing regions were planted with new crops. Remaining opium production shifted south of the Chinese border into the Golden Triangle region.[50] The remnant opium trade primarily served Southeast Asia, but spread to American soldiers during the Vietnam War, with 20 percent of soldiers regarding themselves as addicted during the peak of the epidemic in 1971.

Prohibition outside China

There were no legal restrictions on the importation or use of opium in the United States until the San Francisco Opium Den Ordinance, which banned dens for public smoking of opium in 1875, a measure fueled by anti-Chinese sentiment and the perception that whites were starting to frequent the dens. This was followed by an 1891 California law requiring that narcotics carry warning labels and that their sales be recorded in a registry; amendments to the California Pharmacy and Poison Act in 1907 made it a crime to sell opiates without a prescription, and bans on possession of opium or opium pipes in 1909 were enacted.[91]

At the US federal level, the legal actions taken reflected constitutional restrictions under the enumerated powers doctrine prior to reinterpretation of the commerce clause, which did not allow the federal government to enact arbitrary prohibitions, but did permit arbitrary taxation.[92] Beginning in 1883, opium importation was taxed at US$6 to US$300 per pound, until the Opium Exclusion Act of 1909 prohibited the importation of opium altogether. In a similar manner, the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, passed in fulfillment of the International Opium Convention of 1912, nominally placed a tax on the distribution of opiates, but served as a de facto prohibition of the drugs. Today, opium is regulated by the Drug Enforcement Administration under the Controlled Substances Act.

Following passage of a Colonial Australian law in 1895, Queensland's Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 addressed opium addiction among Aboriginal people, though it soon became a general vehicle for depriving them of basic rights by administrative regulation. By 1905 all Australian states and territories had passed similar laws making prohibitions to Opium sale. Smoking and possession was prohibited in 1908.[93]

Hardening of Canadian attitudes toward Chinese opium users and fear of a spread of the drug into the white population led to the effective criminalization of opium for nonmedical use in Canada between 1908 and the mid-1920s.[94]

In 1909, the International Opium Commission was founded, and by 1914, 34 nations had agreed that the production and importation of opium should be diminished. In 1924, 62 nations participated in a meeting of the Commission. Subsequently, this role passed to the League of Nations, and all signatory nations agreed to prohibit the import, sale, distribution, export, and use of all narcotic drugs, except for medical and scientific purposes. This role was later taken up by the International Narcotics Control Board of the United Nations under Article 23 of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, and subsequently under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances. Opium-producing nations are required to designate a government agency to take physical possession of licit opium crops as soon as possible after harvest and conduct all wholesaling and exporting through that agency.[1]

Indochina tax

From 1897 to 1902, Paul Doumer (later President of France) was Governor-General of French Indochina. Upon his arrival the colonies were losing millions of francs each year. Determined to put them on a paying basis he levied taxes on various products, opium among them. The Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians who could or would not pay these taxes, lost their houses and land, and often became day laborers. Evidently, resorting to this means of gaining income gave France a vested interest in the continuation of opium use among the population of Indochina.

Regulation in Britain and the United States

Before the 1920s, regulation in Britain was controlled by pharmacists. Pharmacists who were found to have prescribed opium for illegitimate uses and anyone found to have sold opium without proper qualifications would be prosecuted.[95] With the passing of the Rolleston Act in Britain in 1926, doctors were allowed to prescribe opiates such as morphine and heroin if they believed their patients demonstrated a medical need. Because addiction was viewed as a medical problem rather than an indulgence, doctors were permitted to allow patients to wean themselves off opiates rather than cutting off any opiate use altogether.[96] The passing of the Rolleston Act put the control of opium use in the hands of medical doctors instead of pharmacists. Later in the 20th century, addiction to opiates, especially heroin in young people, continued to rise and so the sale and prescription of opiates was limited to doctors in treatment centers. If these doctors were found to be prescribing opiates without just cause, then they could lose their license to practice or prescribe drugs.[96]

Abuse of opium in the United States began in the late 19th century and was largely associated with Chinese immigrants. During this time the use of opium had little stigma; the drug was used freely until 1882 when a law was passed to confine opium smoking to specific dens.[96] Until the full ban on opium-based products came into effect just after the beginning of the twentieth century, physicians in the US considered opium a miracle drug that could help with many ailments. Therefore, the ban on said products was more a result of negative connotations towards its use and distribution by Chinese immigrants who were heavily persecuted during this particular period in history.[96] As the 19th century progressed however, doctor Hamilton Wright worked to decrease the use of opium in the US by submitting the Harrison Act to congress. This act put taxes and restrictions on the sale and prescription of opium, as well as trying to stigmatize the opium poppy and its derivatives as "demon drugs", to try to scare people away from them.[96] This act and the stigma of a demon drug on opium, led to the criminalization of people that used opium-based products. It made the use and possession of opium and any of its derivatives illegal. The restrictions were recently redefined by the Federal Controlled Substances Act of 1970.[97][98]

20th-century use

During the Communist era in Eastern Europe, poppy stalks sold in bundles by farmers were processed by users with household chemicals to make kompot ("Polish heroin"), and poppy seeds were used to produce koknar, an opiate.[99]

Obsolescence

Globally, opium has gradually been superseded by a variety of purified, semi-synthetic, and synthetic opioids with progressively stronger effects, and by other general anesthetics. This process began in 1804, when Friedrich Wilhelm Adam Sertürner first isolated morphine from the opium poppy.[100][101] The process continued until 1817, when Sertürner published the isolation of pure morphine from opium after at least thirteen years of research and a nearly disastrous trial on himself and three boys.[102] The great advantage of purified morphine was that a patient could be treated with a known dose—whereas with raw plant material, as Gabriel Fallopius once lamented, "if soporifics are weak they do not help; if they are strong they are exceedingly dangerous." Morphine was the first pharmaceutical isolated from a natural product, and this success encouraged the isolation of other alkaloids: by 1820, isolations of noscapine, strychnine, veratrine, colchicine, caffeine, and quinine were reported. Morphine sales began in 1827, by Heinrich Emanuel Merck of Darmstadt, and helped him expand his family pharmacy into the Merck KGaA pharmaceutical company.

Codeine was isolated in 1832 by Pierre Jean Robiquet.

The use of diethyl ether and chloroform for general anesthesia began in 1846–1847, and rapidly displaced the use of opiates and tropane alkaloids from Solanaceae due to their relative safety.[103]

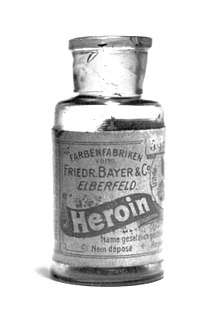

Heroin, the first semi-synthetic opioid, was first synthesized in 1874, but was not pursued until its rediscovery in 1897 by Felix Hoffmann at the Bayer pharmaceutical company in Elberfeld, Germany. From 1898 to 1910 heroin was marketed as a non-addictive morphine substitute and cough medicine for children. Because the lethal dose of heroin was viewed as a hundred times greater than its effective dose, heroin was advertised as a safer alternative to other opioids.[104] By 1902, sales made up 5 percent of the company's profits, and "heroinism" had attracted media attention.[105] Oxycodone, a thebaine derivative similar to codeine, was introduced by Bayer in 1916 and promoted as a less-addictive analgesic. Preparations of the drug such as oxycodone with paracetamol and extended release oxycodone remain popular to this day.

A range of synthetic opioids such as methadone (1937), pethidine (1939), fentanyl (late 1950s), and derivatives thereof have been introduced, and each is preferred for certain specialized applications. Nonetheless, morphine remains the drug of choice for American combat medics, who carry packs of syrettes containing 16 milligrams each for use on severely wounded soldiers.[106] No drug has been found that can match the painkilling effect of opioids without also duplicating much of their addictive potential.

Modern production and use

.jpg)

Opium was prohibited in many countries during the early 20th century, leading to the modern pattern of opium production as a precursor for illegal recreational drugs or tightly regulated, highly taxed, legal prescription drugs. In 1980, 2,000 tons of opium supplied all legal and illegal uses.[21] Worldwide production in 2006 was 6610 metric tons[107]—about one-fifth the level of production in 1906, since then, opium production has fallen.

In 2002, the price for one kilogram of opium was US$300 for the farmer, US$800 for purchasers in Afghanistan, and US$16,000 on the streets of Europe before conversion into heroin.[4]

Recently, opium production has increased considerably, surpassing 5,000 tons in 2002 and reaching 8,600 tons in Afghanistan and 840 tons in the Golden Triangle in 2014. Production is expected to increase in 2015 as new, improved seeds have been brought into Afghanistan.[108][109] The World Health Organization has estimated that current production of opium would need to increase fivefold to account for total global medical need.[51]

Papaver somniferum

Opium poppies are popular and attractive garden plants, whose flowers vary greatly in color, size and form. A modest amount of domestic cultivation in private gardens is not usually subject to legal controls. In part, this tolerance reflects variation in addictive potency. A cultivar for opium production, Papaver somniferum L. elite, contains 91.2 percent morphine, codeine, and thebaine in its latex alkaloids, whereas in the latex of the condiment cultivar "Marianne", these three alkaloids total only 14.0 percent. The remaining alkaloids in the latter cultivar are primarily narcotoline and noscapine.[110]

Seed capsules can be dried and used for decorations, but they also contain morphine, codeine, and other alkaloids. These pods can be boiled in water to produce a bitter tea that induces a long-lasting intoxication (See Poppy tea). If allowed to mature, poppy pods (poppy straw) can be crushed and used to produce lower quantities of morphinans. In poppies subjected to mutagenesis and selection on a mass scale, researchers have been able to use poppy straw to obtain large quantities of oripavine, a precursor to opioids and antagonists such as naltrexone.[111] Although millennia older, the production of poppy head decoctions can be seen as a quick-and-dirty variant of the Kábáy poppy straw process, which since its publication in 1930 has become the major method of obtaining licit opium alkaloids worldwide, as discussed in Morphine.

Poppy seeds are a common and flavorsome topping for breads and cakes. One gram of poppy seeds contains up to 33 micrograms of morphine and 14 micrograms of codeine, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in the United States formerly mandated that all drug screening laboratories use a standard cutoff of 300 nanograms per milliliter in urine samples. A single poppy seed roll (0.76 grams of seeds) usually did not produce a positive drug test, but a positive result was observed from eating two rolls. A slice of poppy seed cake containing nearly five grams of seeds per slice produced positive results for 24 hours. Such results are viewed as false positive indications of drug use and were the basis of a legal defense.[112][113] On November 30, 1998, the standard cutoff was increased to 2000 nanograms (two micrograms) per milliliter.[114] Confirmation by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry will distinguish amongst opium and variants including poppy seeds, heroin, and morphine and codeine pharmaceuticals by measuring the morphine:codeine ratio and looking for the presence of noscapine and acetylcodeine, the latter of which is only found in illicitly produced heroin, and heroin metabolites such as 6-monoacetylmorphine.[115]

Harvesting and processing

When grown for opium production, the skin of the ripening pods of these poppies is scored by a sharp blade at a time carefully chosen so that rain, wind, and dew cannot spoil the exudation of white, milky latex, usually in the afternoon. Incisions are made while the pods are still raw, with no more than a slight yellow tint, and must be shallow to avoid penetrating hollow inner chambers or loculi while cutting into the lactiferous vessels. In the Indian Subcontinent, Afghanistan, Central Asia and Iran, the special tool used to make the incisions is called a nushtar or "nishtar" (from Persian, meaning a lancet) and carries three or four blades three millimeters apart, which are scored upward along the pod. Incisions are made three or four times at intervals of two to three days, and each time the "poppy tears", which dry to a sticky brown resin, are collected the following morning. One acre harvested in this way can produce three to five kilograms of raw opium.[116] In the Soviet Union, pods were typically scored horizontally, and opium was collected three times, or else one or two collections were followed by isolation of opiates from the ripe capsules. Oil poppies, an alternative strain of P. somniferum, were also used for production of opiates from their capsules and stems.[117] A traditional Chinese method of harvesting opium latex involved cutting off the heads and piercing them with a coarse needle then collecting the dried opium 24 to 48 hours later.

Raw opium may be sold to a merchant or broker on the black market, but it usually does not travel far from the field before it is refined into morphine base, because pungent, jelly-like raw opium is bulkier and harder to smuggle. Crude laboratories in the field are capable of refining opium into morphine base by a simple acid-base extraction. A sticky, brown paste, morphine base is pressed into bricks and sun-dried, and can either be smoked, prepared into other forms or processed into heroin.[14]

Other methods of preparation (besides smoking), include processing into regular opium tincture (tinctura opii), laudanum, paregoric (tinctura opii camphorata), herbal wine (e.g., vinum opii), opium powder (pulvis opii), opium sirup (sirupus opii) and opium extract (extractum opii).[118] Vinum opii is made by combining sugar, white wine, cinnamon, and cloves. Opium syrup is made by combining 97.5 part sugar syrup with 2.5 parts opium extract. Opium extract (extractum opii) finally can be made by macerating raw opium with water. To make opium extract, 20 parts water are combined with 1 part raw opium which has been boiled for 5 minutes (the latter to ease mixing).[118]

Heroin is widely preferred because of increased potency. One study in postaddicts found heroin to be approximately 2.2 times more potent than morphine by weight with a similar duration; at these relative quantities, they could distinguish the drugs subjectively but had no preference.[119] Heroin was also found to be twice as potent as morphine in surgical anesthesia.[120] Morphine is converted into heroin by a simple chemical reaction with acetic anhydride, followed by purification.[121][122] Especially in Mexican production, opium may be converted directly to "black tar heroin" in a simplified procedure. This form predominates in the U.S. west of the Mississippi. Relative to other preparations of heroin, it has been associated with a dramatically decreased rate of HIV transmission among intravenous drug users (4 percent in Los Angeles vs. 40 percent in New York) due to technical requirements of injection, although it is also associated with greater risk of venous sclerosis and necrotizing fasciitis.[123]

Illegal production

Afghanistan is currently the primary producer of the drug. After regularly producing 70 percent of the world's opium, Afghanistan decreased production to 74 tons per year under a ban by the Taliban in 2000, a move which cut production by 94 percent. A year later, after American and British troops invaded Afghanistan, removed the Taliban and installed the interim government, the land under cultivation leapt back to 285 square miles (740 km2), with Afghanistan supplanting Burma to become the world's largest opium producer once more. Opium production in that country has increased rapidly since,[124][125] reaching an all-time high in 2006. According to DEA statistics, Afghanistan's production of oven-dried opium increased to 1,278 tons in 2002, more than doubled by 2003, and nearly doubled again during 2004. In late 2004, the U.S. government estimated that 206,000 hectares were under poppy cultivation, 4.5 percent of the country's total cropland, and produced 4,200 metric tons of opium, 76 percent of the world's supply, yielding 60 percent of Afghanistan's gross domestic product.[126] In 2006, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime estimated production to have risen 59 percent to 165,000 hectares (407,000 acres) in cultivation, yielding 6,100 tons of opium, 82 percent of the world's supply.[127] The value of the resulting heroin was estimated at US$3.5 billion, of which Afghan farmers were estimated to have received US$700 million in revenue. For farmers, the crop can be up to ten times more profitable than wheat. The price of opium is around US$138 per kilo. Opium production has led to rising tensions in Afghan villages. Though direct conflict has yet to occur, the opinions of the new class of young rich men involved in the opium trade are at odds with those of the traditional village leaders.[128]

An increasingly large fraction of opium is processed into morphine base and heroin in drug labs in Afghanistan. Despite an international set of chemical controls designed to restrict availability of acetic anhydride, it enters the country, perhaps through its Central Asian neighbors which do not participate. A counternarcotics law passed in December 2005 requires Afghanistan to develop registries or regulations for tracking, storing, and owning acetic anhydride.[129]

Besides Afghanistan, smaller quantities of opium are produced in Pakistan, the Golden Triangle region of Southeast Asia (particularly Burma), Colombia, Guatemala, and Mexico.

Chinese production mainly trades with and profits from North America. In 2002, they were seeking to expand through eastern United States. In the post 9/11 era, trading between borders became difficult and because new international laws were set into place, the opium trade became more diffused. Power shifted from remote to high-end smugglers and opium traders. Outsourcing became a huge factor for survival for many smugglers and opium farmers.[130]

Legal production

Legal opium production is allowed under the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs and other international drug treaties, subject to strict supervision by the law enforcement agencies of individual countries. The leading legal production method is the Gregory process, whereby the entire poppy, excluding roots and leaves, is mashed and stewed in dilute acid solutions. The alkaloids are then recovered via acid-base extraction and purified. This process was developed in the UK during World War II, when wartime shortages of many essential drugs encouraged innovation in pharmaceutical processing.

Legal opium production in India is much more traditional. As of 2008, opium was collected by farmers who were licensed to grow 0.1 hectares (0.25 acres) of opium poppies, who to maintain their licences needed to sell 56 kilograms of unadulterated raw opium paste. The price of opium paste is fixed by the government according to the quality and quantity tendered. The average is around 1500 rupees (US$29) per kilogram.[131] Some additional money is made by drying the poppy heads and collecting poppy seeds, and a small fraction of opium beyond the quota may be consumed locally or diverted to the black market. The opium paste is dried and processed into government opium and alkaloid factories before it is packed into cases of 60 kilograms for export. Purification of chemical constituents is done in India for domestic production, but typically done abroad by foreign importers.[132]

Legal opium importation from India and Turkey is conducted by Mallinckrodt, Noramco, Abbott Laboratories, Purdue Pharma, and Cody Laboratories Inc. in the United States, and legal opium production is conducted by GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Johnson Matthey, and Mayne in Tasmania, Australia; Sanofi Aventis in France; Shionogi Pharmaceutical in Japan; and MacFarlan Smith in the United Kingdom.[133] The UN treaty requires that every country submit annual reports to the International Narcotics Control Board, stating that year's actual consumption of many classes of controlled drugs as well as opioids and projecting required quantities for the next year. This is to allow trends in consumption to be monitored and production quotas allotted.

In 2005, the European Senlis Council began developing a programme which hopes to solve the problems caused by the large quantity of opium produced illegally in Afghanistan, most of which is converted to heroin and smuggled for sale in Europe and the United States. This proposal is to license Afghan farmers to produce opium for the world pharmaceutical market, and thereby solve another problem, that of chronic underuse of potent analgesics where required within developing nations. Part of the proposal is to overcome the "80–20 rule" that requires the U.S. to purchase 80 percent of its legal opium from India and Turkey to include Afghanistan, by establishing a second-tier system of supply control that complements the current INCB regulated supply and demand system by providing poppy-based medicines to countries who cannot meet their demand under the current regulations. Senlis arranged a conference in Kabul that brought drug policy experts from around the world to meet with Afghan government officials to discuss internal security, corruption issues, and legal issues within Afghanistan.[134] In June 2007, the Council launched a "Poppy for Medicines" project that provides a technical blueprint for the implementation of an integrated control system within Afghan village-based poppy for medicine projects: the idea promotes the economic diversification by redirecting proceeds from the legal cultivation of poppy and production of poppy-based medicines (See Senlis Council).[135] There has been criticism of the Senlis report findings by Macfarlan Smith, who argue that though they produce morphine in Europe, they were never asked to contribute to the report.[136]

Cultivation in the UK

In late 2006, the British government permitted the pharmaceutical company MacFarlan Smith (a Johnson Matthey company) to cultivate opium poppies in England for medicinal reasons, after Macfarlan Smith's primary source, India, decided to increase the price of export opium latex. This move is well received by British farmers, with a major opium poppy field located in Didcot, England. The British government has contradicted the Home Office's suggestion that opium cultivation can be legalized in Afghanistan for exports to the United Kingdom, helping lower poverty and internal fighting while helping the NHS to meet the high demand for morphine and heroin. Opium poppy cultivation in the United Kingdom does not need a licence, but a licence is required for those wishing to extract opium for medicinal products.[137]

Consumption

In the industrialized world, the United States is the world's biggest consumer of prescription opioids, with Italy one of the lowest because of tighter regulations on prescribing narcotics for pain relief.[138] Most opium imported into the United States is broken down into its alkaloid constituents, and whether legal or illegal, most current drug use occurs with processed derivatives such as heroin rather than with unrefined opium.

Intravenous injection of opiates is most used: by comparison with injection, "dragon chasing" (heating of heroin on a piece of foil), and madak and "ack ack" (smoking of cigarettes containing tobacco mixed with heroin powder) are only 40 percent and 20 percent efficient, respectively.[139] One study of British heroin addicts found a 12-fold excess mortality ratio (1.8 percent of the group dying per year).[140] Most heroin deaths result not from overdose per se, but combination with other depressant drugs such as alcohol or benzodiazepines.[141]

The smoking of opium does not involve the burning of the material as might be imagined. Rather, the prepared opium is indirectly heated to temperatures at which the active alkaloids, chiefly morphine, are vaporized. In the past, smokers would use a specially designed opium pipe which had a removable knob-like pipe-bowl of fired earthenware attached by a metal fitting to a long, cylindrical stem.[142] A small "pill" of opium about the size of a pea would be placed on the pipe-bowl, which was then heated by holding it over an opium lamp, a special oil lamp with a distinct funnel-like chimney to channel heat into a small area. The smoker would lie on his or her side in order to guide the pipe-bowl and the tiny pill of opium over the stream of heat rising from the chimney of the oil lamp and inhale the vaporized opium fumes as needed. Several pills of opium were smoked at a single session depending on the smoker's tolerance to the drug. The effects could last up to twelve hours.

In Eastern culture, opium is more commonly used in the form of paregoric to treat diarrhea. This is a weaker solution than laudanum, an alcoholic tincture which was prevalently used as a pain medication and sleeping aid. Tincture of opium has been prescribed for, among other things, severe diarrhea.[143] Taken thirty minutes prior to meals, it significantly slows intestinal motility, giving the intestines greater time to absorb fluid in the stool.

Despite the historically negative view of opium as a cause of addiction, the use of morphine and other derivatives isolated from opium in the treatment of chronic pain has been reestablished. If given in controlled doses, modern opiates can be an effective treatment for neuropathic pain and other forms of chronic pain.[144]

Chemical and physiological properties

Opium contains two main groups of alkaloids. Phenanthrenes such as morphine, codeine, and thebaine are the main psychoactive constituents.[145] Isoquinolines such as papaverine and noscapine have no significant central nervous system effects. Morphine is the most prevalent and important alkaloid in opium, consisting of 10–16 percent of the total, and is responsible for most of its harmful effects such as lung edema, respiratory difficulties, coma, or cardiac or respiratory collapse. Morphine binds to and activates mu opioid receptors in the brain, spinal cord, stomach and intestine. Regular use can lead to drug tolerance or physical dependence. Chronic opium addicts in 1906 China[50] or modern-day Iran[146] consume an average of eight grams of opium daily.

Both analgesia and drug addiction are functions of the mu opioid receptor, the class of opioid receptor first identified as responsive to morphine. Tolerance is associated with the superactivation of the receptor, which may be affected by the degree of endocytosis caused by the opioid administered, and leads to a superactivation of cyclic AMP signaling.[147] Long-term use of morphine in palliative care and the management of chronic pain always entails a risk that the patient develops tolerance or physical dependence. There are many kinds of rehabilitation treatment, including pharmacologically based treatments with naltrexone, methadone, or ibogaine.[148]

Slang terms

Some slang terms for opium include: "Big O", "Shanghai Sally", "dope", "hop", "midnight oil", "O.P.", and "tar". "Dope" and "tar" can also refer to heroin. The traditional opium pipe is known as a "dream stick".[149] The term dope entered the English language in the early nineteenth century, originally referring to viscous liquids, particularly sauces or gravy.[150] It has been used to refer to opiates since at least 1888, and this usage arose because opium, when prepared for smoking, is viscous.[150]

See also

- Golden Crescent

- Golden Triangle

- History of Jardine, Matheson & Co.

- Illegal drug trade in Colombia

- Mexican Drug War

- Nabidh

- Opium replacement

- Protocol for Limiting and Regulating the Cultivation of the Poppy Plant, the Production of, International and Wholesale Trade in, and Use of Opium

- Psychoactive drug

- Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade

- Morphine

- Heroin

References

- Paul L. Schiff, Jr. (2002). "Opium and its alkaloids". American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. Archived from the original on October 21, 2007. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- Professor Arthur C. Gibson. "The Pernicious Opium Poppy". University of California, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- "The Global Heroin Market" (PDF). October 2014.

- Mark Corcoran. "Afghanistan: America's blind eye". Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved May 11, 2007.

- "Opium definition". Drugs.com. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- Simon O'Dochartaigh. "HON Mother & Child Glossary, Meconium". hon.ch. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- Sawynok J (January 1986). "The therapeutic use of heroin: a review of the pharmacological literature". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 64 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1139/y86-001. PMID 2420426.

- "Opium (Drugs / Substance Abuse) - UrbanAreas.net". UrbanAreas.net. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- Merlin, M. D. (January 1, 2003). "Archaeological Evidence for the Tradition of Psychoactive Plant Use in the Old World" (PDF). Economic Botany. 57 (3): 295–323. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0295:aeftto]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4256701.

- PAPADAKI, P. G. KRITIKOS, S. P. "The history of the poppy and of opium and their expansion in antiquity in the eastern Mediterranean area". www.unodc.org. UNODC- Bulletin on Narcotics – 1967 Issue 4 – 002. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- Santella, Thomas M.; Triggle, D. J. (2009). Opium. Facts On File, Incorporated. p. 8. ISBN 9781438102139.

- Suzanne Carr (1995). "MS thesis". Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved May 16, 2007. (citing Andrew Sherratt)

- M J Brownstein (June 15, 1993). "A brief history of opiates, opioid peptides, and opioid receptors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (12): 5391–5393. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.5391B. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.12.5391. PMC 46725. PMID 8390660.

- PBS Frontline (1997). "The Opium Kings". Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- P. G. Kritikos & S. P. Papadaki (January 1, 1967). "The early history of the poppy and opium". Journal of the Archaeological Society of Athens.

- E. Guerra Doce (January 1, 2006). "Evidencias del consumo de drogas en Europa durante la Prehistoria". Trastornos Adictivos (in Spanish). 8 (1): 53–61. doi:10.1016/S1575-0973(06)75106-6. Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2007. (includes image)

- Ibrahim B. Syed. "Alcohol and Islam". Retrieved July 7, 2005.

- "Islamic Medical Manuscripts at the National Library of Medicine: a note on pharmaceutics". Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- Julius Berendes (1902). "De Materia Medica" (in German). Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved May 10, 2007.

- Philip Robson (1999). Forbidden Drugs. Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-19-262955-5.

- Carl A. Trocki (2002). "Opium as a commodity and the Chinese drug plague" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2008. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- "Answers.com: al-Razi".

- "Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (841–926)". Saudi Aramco World. January 2002. Retrieved January 12, 2008.

- "El Zahrawi – Father Of Surgery". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved May 4, 2007.

- Heydari, M; Hashempur, M. H.; Zargaran, A (2013). "Medicinal aspects of opium as described in Avicenna's Canon of Medicine". Acta Medico-historica Adriatica. 11 (1): 101–12. PMID 23883087.

- Smith RD (October 1980). "Avicenna and the Canon of Medicine: a millennial tribute". The Western Journal of Medicine. 133 (4): 367–70. PMC 1272342. PMID 7051568.

- Ganidagli, Suleyman M.D., Cengiz, Mustafa M.D., Aksoy, Sahin M.D., Verit, Ayhan M.D. (January 2004). "Approach to Painful Disorders by Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu in the Fifteenth Century Ottoman Period". Anesthesiology. 100 (1): 165–169. doi:10.1097/00000542-200401000-00026. PMID 14695738. Retrieved May 4, 2007.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Pseudo-Apuleius: Papaver". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- "Paracelsus: the philosopher's stone made flesh". Retrieved May 4, 2007.

- "The devil's doctor". Retrieved May 4, 2007.

- "PARACELSUS, Five Hundred Years: Three American Exhibits". Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- Stephen Harding; Lee Ann Olivier & Olivera Jokic. "Victorians' Secret: Victorian Substance Abuse". Archived from the original on May 31, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2007.

- Ole Daniel Enersen. "Thomas Sydenham". Retrieved May 2, 2007.

- Aurin, Marcus (January 1, 2000). "Chasing the Dragon: The Cultural Metamorphosis of Opium in the United States, 1825–1935". Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 14 (3): 414–441. doi:10.1525/maq.2000.14.3.414. JSTOR 649506. PMID 11036586.

- Kramer John C (1979). "Opium Rampant: Medical Use, Misuse and Abuse in Britain and the West in the 17th and 18th Centuries". British Journal of Addiction. 74 (4): 377–389. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1979.tb01367.x. PMID 396938.

- Donna Young (April 15, 2007). "Scientists Examine Pain Relief and Addiction". Archived from the original on December 6, 2007. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- "Drug Addiction Research and the Health of Women – pg. 33–52" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 22, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- Zhang, Sarah (January 9, 2019). "Why a Medieval Woman Had Lapis Lazuli Hidden in Her Teeth". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Garzoni, Costantino. 1840 [1573]. "Relazione dell'impero Ottomano del senatore Costantino Garzoni stato all'ambascieria di Costantinopoli nel 1573". In Le relazioni degli ambasciatori veneti al Senato, serie III, volume I, ed. Eugenio Albèri. Firenze: Clio, p. 398

- Hamarneh Sami (1972). "Pharmacy in medieval Islam and the history of drug addiction". Medical History. 16 (3): 226–237. doi:10.1017/s0025727300017725. PMC 1034978. PMID 4595520.

- Michot, Yahya. L’opium et le café. Traduction d’un texte arabe anonyme et exploration de l'opiophagie ottomane (Beirut: Albouraq, 2008) ISBN 978-2-84161-397-7

- Dikotter, Frank (2004). Narcotic Culture: A History of Drugs in China. Hurst. p. 3. ISBN 978-0226149059.

- de Quincey, Thomas (1821). Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. p. 188.

- Hubble D (October 1957). "Opium Addiction and English Literature". Medical History. 1 (4): 323–35. doi:10.1017/s0025727300021505. PMC 1034310. PMID 13476921.

- Matthee, Rudi. The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian History, 1500–1900 (Washington: Mage Publishers, 2005), pp. 97–116 ISBN 0-934211-64-7. Van de Wijngaart, G., "Trading in Dreams", in P. Faber & al. (eds.), Dreaming of Paradise: Islamic Art from the Collection of the Museum of Ethnology, Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Martial & Snoeck, 1993, p. 186-191.

- Habighorst, Ludwig V., Reichart, Peter A., Sharma, Vijay, Love for Pleasure: Betel, Tobacco, Wine and Drugs in Indian Miniatures (Koblenz: Ragaputra Edition, 2007)

- Yangwen Zheng (2003). "The Social Life of Opium in China, 1483–1999". Modern Asian Studies. 37 (1): 1–39. doi:10.1017/S0026749X0300101X.

- Opium : Dikotter, Frank, Lars Laamann and Zhou Xun. 2004. Narcotic Culture: A History of Drugs in China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; Zheng Yangwen. 2005. The Social Life of Opium in China. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Dikötter, Frank; Lars Laamann; and Zhou Xun Narcotic Culture: A History of Drugs in China. Co-published with C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-0-226-14905-9 (ISBN 0-226-14905-6) Spring 2004. Archived May 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Alfred W. McCoy. "Opium History, 1858 to 1940". Archived from the original on April 4, 2007. Retrieved May 4, 2007.

- Rewriting history, A response to the 2008 World Drug Report, Transnational Institute, June 2008

- Commissioner Jesse B. Cook (June 1931). "San Francisco's Old Chinatown". San Francisco Police and Peace Officers' Journal. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- H.H. Kane, M.D. (September 24, 1881). "American Opium Smokers". Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- "Opium degrading the French Navy". April 27, 1913. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Alfred W. McCoy (1972). "The politics of heroin in Southeast Asia". Archived from the original on October 7, 2007. Retrieved September 24, 2007.

- John Richards (May 23, 2001). "Opium and the British Indian Empire". Retrieved September 24, 2007.

- John Rennie (March 26, 2007). "When a woman ruled Chinatown". Tower Hamlets Newsletter. Archived from the original on February 10, 2010. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- J.P. Jones (February 1931). "Lascars in the port of London". P.L.A. Monthly. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- "Opium in the West" Archived October 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Opium Museum. 2007. Retrieved on September 21, 2007.

- "Brilliant, Chang! « London Particulars". Retrieved on October 3, 2010.

- "Opium timeline". The Golden Triangle. Archived from the original on June 26, 2008. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- "Opium Factories of Bihar – Bihargatha". Bihargatha.in. Archived from the original on September 10, 2011. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- Dalrymple, William (March 4, 2015). "The East India Company: The original corporate raiders". The Guardian. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- Wertz, Richard R. "Qing Era (1644–1912)". iBiblio. 1998. Retrieved on September 21, 2007.

- John K. Fairbanks, "The Creation of the Treaty System' in John K. Fairbanks, ed. The Cambridge History of China, vol. 10 Part 1 (Cambridge University Press, 1992) p. 213. cited in John Newsinger (October 1997). "Britain's opium wars – fact and myth about the opium trade in the East". Monthly Review. Archived from the original on February 13, 2006.

- Bradley, James (2009). The Imperial Cruise: a secret history of empire and war. Little, Brown and Company. pp. 274–275. ISBN 978-0-316-00895-2.

- Kathleen L. Lodwick (February 5, 2015). Crusaders Against Opium: Protestant Missionaries in China, 1874–1917. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-0-8131-4968-4.

- Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy (2009). Opium: Uncovering the Politics of the Poppy. Harvard University Press. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-0-674-05134-8.

- Dr Roland Quinault; Dr Ruth Clayton Windscheffel; Mr Roger Swift (July 28, 2013). William Gladstone: New Studies and Perspectives. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 238–. ISBN 978-1-4094-8327-4.

- Ms Louise Foxcroft (June 28, 2013). The Making of Addiction: The 'Use and Abuse' of Opium in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-1-4094-7984-0.

- William Travis Hanes; Frank Sanello (2004). Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Sourcebooks, Inc. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-1-4022-0149-3.

- W. Travis Hanes III; Frank Sanello (February 1, 2004). The Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Sourcebooks. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-1-4022-5205-1.

- Peter Ward Fay (November 9, 2000). The Opium War, 1840–1842: Barbarians in the Celestial Empire in the Early Part of the Nineteenth Century and the War by which They Forced Her Gates Ajar. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 290–. ISBN 978-0-8078-6136-3.

- Anne Isba (August 24, 2006). Gladstone and Women. A&C Black. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-1-85285-471-3.

- David William Bebbington (1993). William Ewart Gladstone: Faith and Politics in Victorian Britain. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-0-8028-0152-4.

- Lodwick, Kathleen L. (1996). Crusaders Against Opium: Protestant Missionaries in China 1874–1917. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1924-3

- Windle J (2013). "'Harms Caused by China's 1906–17 Opium Suppression Intervention'" (PDF). International Journal of Drug Policy. 24 (5): 498–505. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.03.001. PMID 23567100.

- Ellen N. La Motte. "The opium monopoly". Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- Joyce A. Madancy (April 2004). "The Troublesome Legacy of Commissioner Lin". Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- Windle, J. (2011). ‘Ominous Parallels and Optimistic Differences: Opium in China and Afghanistan’. Law, Crime and History, Vol. 2(1), pp. 141-164. http://roar.uel.ac.uk/1692/

- William A Callahan (May 8, 2004). "Historical Legacies and Non/Traditional Security: Commemorating National Humiliation Day in China" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2007. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- Ann Heylen (2004). Chronique du Toumet-Ortos: Looking through the Lens of Joseph Van Oost, Missionary in Inner Mongolia (1915–1921). Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press. p. 312. ISBN 978-90-5867-418-0. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- Association for Asian Studies. Southeast Conference (1979). Annals, Volumes 1–5. The Conference. p. 51. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- Edward R. Slack (2001). Opium, State, and Society: China's Narco-Economy and the Guomindang, 1924–1937. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-8248-2361-0. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- Marc Andre Matten, ed. (December 9, 2011). Places of Memory in Modern China: History, Politics, and Identity. BRILL. p. 271. ISBN 978-90-04-21901-4.

- Petr Parfenovich Vladimirov (1975). The Vladimirov diaries: Yenan, China, 1942–1945. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-00928-7.

- Chen Yung-Fa (1995). "The Blooming Poppy under the Red Sun: The Yan'an Way and the Opium Trade". In Tony Saich; Hans J. Van de Ven (eds.). New Perspectives on the Chinese Communist Revolution. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 263–298. ISBN 978-1-56324-428-5.

- Hastings, Max (2007). Retribution. New York: Vintage. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-307-27536-3.