Operation Ichi-Go

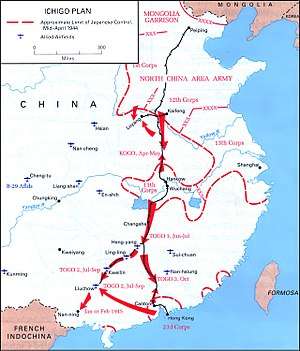

Operation Ichi-Go (一号作戦 Ichi-gō Sakusen, lit. "Operation Number One") was a campaign of a series of major battles between the Imperial Japanese Army forces and the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China, fought from April to December 1944. It consisted of three separate battles in the Chinese provinces of Henan, Hunan and Guangxi.

These battles were the Japanese Operation Kogo or Battle of Central Henan, Operation Togo 1 or the Battle of Changheng, and Operation Togo 2 and Togo 3, or the Battle of Guilin-Liuzhou, respectively. The two primary goals of Ichi-go were to open a land route to French Indochina, and capture air bases in southeast China from which American bombers were attacking the Japanese homeland and shipping.[10]

In Japanese the operation was also called Tairiku Datsū Sakusen (大陸打通作戦), or "Continent Cross-Through Operation", while the Chinese refer to it as the Battle of Henan-Hunan-Guangxi (simplified Chinese: 豫湘桂会战; traditional Chinese: 豫湘桂會戰; pinyin: Yù Xīang Guì Huìzhàn).

Prelude

In 1944, China came off of several victories against Japan in Burma leading to overconfidence. Nationalist China also diverted soldiers to Xinjiang since 1942 to retake the province from the Soviet client Sheng Shicai whose puppet army was backed by the Soviet Red Army 8th Regiment in Hami, Xinjiang since the Soviet invasion of Xinjiang in 1934 when the Soviets occupied northern Xinjiang and Islamic rebellion in Xinjiang in 1937 when the Soviets occupied southern Xinjiang as well placing all of Xinjiang under Sheng Shicai and Soviet Communist control. The fighting then escalated in early 1944 with the Ili Rebellion with Soviet backed Uyghur Communist rebels, causing China to fight enemies on two fronts with 120,000 Chinese soldiers fighting against the Ili rebellion. The aim of the Japanese Operation Ichigo was to destroy American airfields in southern China that threatened the Japanese home islands with bombing and to link railways in Beijing, Hankou and Canton cities from northern China in Beijing to southern China's coast on Canton. Japan was alarmed by American air raids against Japanese forces in Taiwan's Hsinchu airfield by American bombers based in southern China, correctly deducing that southern China could become the base of a major American bombing campaign against the Japanese home islands so Japan resolved to destroy and capture all airbases where American bombers operated from in Operation Ichigo.

Chiang Kai-shek and the Republic of China authorities deliberately ignored and dismissed a tip passed on to the Chinese government in Chongqing by the French military that the French picked up in colonial French Indochina on the impending Japanese offensive to link the three cities. The Chinese military believed it to be a fake tip planted by Japan to mislead them since only 30,000 Japanese soldiers started the first manoeuvre of Operation Ichigo in northern China crossing the Yellow river so the Chinese assumed it would be a local operation in northern China only. Another major factor was that the battlefront between China and Japan was static and stabilized since 1940 and continued for four years that way until Operation Ichigo in 1944 so Chiang assumed that Japan would continue the same posture and remain behind the lines in pre-1940 occupied territories of North China only bolstering the puppet Chinese government of Wang Jingwei and exploiting resources there.

The Japanese had indeed acted this way for most of the 1940s from 1940-1944, with the Japanese only making a few failed weak attempts to capture China's provisional capital in Chongqing on the Yangtze river which they quickly abandoned and gave up on before 1944. Japan also exhibited no intention before of linking the transcontinental Beijing Hankow Canton railways. China also was confident by its three victories in a row defending Changsha against Japan, Battle of Changsha (1939), Battle of Changsha (1941), and Battle of Changsha (1942). China had also defeated Japan in the India-Burma theater in Southeast Asia with X Force and Y Force and the Chinese could not believe Japan had carelessly let information slip into French hands, believing Japan deliberately fed misinformation to the French to divert Chinese troops from India and Burma towards China. China believed the Burma theater to be far more important for Japan than southern China and that Japanese forces in southern China would continue to assume a defensive posture only.

China believed the initial Japanese attack in Ichigo to be a localized feint and distraction in northern China so Chinese troops numbering 400,000 in North China deliberately withdrew without a fight when Japan attacked, assuming it was just another localized Japanese operation where the Japanese would withdraw after attacking. This mistake led to the collapse of Chinese defensive lines as the Japanese soldiers which eventually numbered in the hundreds of thousands far more than the original 30,000 Japanese kept pressing the attack from northern China to central China to southern China's provinces as Chinese soldiers deliberately withdrew leading to confusion and collapse, except at the Defense of Hengyang where 17,000 outnumbered Chinese soldiers held out against over 110,000 Japanese soldiers for months in the longest siege of the war inflicting 19,000-60,000 deaths on the Japanese.

At Tushan in Guizhou province, the Nationalist government of China was forced to deploy 5 armies of the 8th war zone that they were using in the entire war up to Ichigo to contain the Communist Chinese to instead fight Japan. But at that point, dietary deficiencies of Japanese soldiers and increasing casualties suffered by Japan forced Japan to end Operation Ichigo in Guizhou causing the operation to cease. After Operation Ichigo, Chiang Kai-shek started a plan to withdrew Chinese troops from the Burma theatre against Japan in Southeast Asia for a counter offensive called "White Tower" and "Iceman" against Japanese soldiers in China in 1945.[11]

Campaign

There were two phases to the operation. In the first phase, the Japanese secured the Pinghan Railway between Beijing and Wuhan; in the second, they displaced the US air forces stationed in Hunan province and reached the city of Liuzhou, near the border with Japanese-held Indochina. 17 divisions, including 500,000 men, 15,000 vehicles, 6,000 artillery pieces, 800 tanks and 100,000 horses participated in this operation.

The Japanese included Kwantung Army units and equipment from Manchukuo, mechanized units, units from the North China theater and units from mainland Japan to participate in this campaign. It was the largest land campaign organized by the Japanese during the entire Second Sino-Japanese War. Many of the newest American-trained Chinese units and supplies were forcibly locked in the Burmese theater under Joseph Stilwell set by terms of the Lend-Lease Agreement.

In Operation Kogo, 390,000 Chinese soldiers, led by General Tang Enbo (湯恩伯), were deployed to defend the strategic position of Luoyang. The 3rd Tank Division of the IJA crossed the Yellow River around Zhengzhou in late April and defeated Chinese forces near Xuchang, then swung around clockwise and besieged Luoyang. Luoyang was defended by three Chinese divisions. The 3rd Tank Division began to attack Luoyang on May 13 and took it on May 25.

The second phase of Ichigo began in May, following the success of the first phase. Japanese forces advanced southward and occupied Changsha, Hengyang, Guilin and Liuzhou. At the Defense of Hengyang, the Japanese only won a Pyrrhic victory since 17,000 Chinese soldiers held out against over 110,000 Japanese soldiers from June 22–August 8, 1944,inflicting 19,000-60,000 dead on the Japanese. In December 1944, Japanese forces reached French Indochina and achieved the purpose of the operation. Nevertheless, there were few practical gains from this offensive. US air forces moved inland from the threatened bases near the coast. The operation also forced British Commandos working with the Chinese as part of Mission 204 to leave China and return to Burma. The U.S. Fourteenth Air Force often disrupted the Hunan–Guangxi Railway between Hengyang and Liuzhou that had been established in Operation Ichigo. Japan continued to attack airfields where US air forces were stationed up to the spring of 1945.

The XX Bomber Command operating Strategic B-29 bombers of the Twentieth Air Force, which were attacking Japan in Operation Matterhorn, were forced to move as well, but although this affected their efficiency for a short time, in early 1945 the Twentieth Air Force moved to newly established bases in the Marianas under the command of the newly established XXI Bomber Command. This nullified the limited protection that the Japanese home islands had received from Operation Ichigo.

Henan peasants attack Kuomintang forces

General Jiang Dingwen of the First War Zone gave his account of the behavior of Henan civilians: "During the campaign, the unexpected phenomenon was that the people of the mountains in western Henan attacked our troops, taking guns, bullets, and explosives, and even high-powered mortars and radio equipment... They surrounded our troops and killed our officers. We heard this pretty often. The heads of the villages and baojia (village mutual-responsibility groups) just ran away. At the same time, they took away our stored grain, leaving their houses and fields empty, which meant that our officers and soldiers had no food for many days."[12] This was revenge for the 1938 Yellow River flood and the Chinese famine of 1942–43.[13] General Jiang's account also said: "Actually this is truly painful for me to say: in the end the damages we suffered from the attacks by the people were more serious than the losses from battles with the enemy."[14] The Henan peasants picked up the weapons Kuomintang troops had abandoned to defend themselves against the Japanese.[15] When the Kuomintang army ordered the Henan locals to destroy the local highways to prevent the Japanese advance, they refused.[16] In fact they sometimes even went back at night and mended roads which the army had torn up by day.[17]

Aftermath

With the rapid deterioration of the Chinese front after Japanese launched Operation Ichi-Go in 1944, General Joseph Stilwell saw this as an opportunity to win his political struggle against Chiang Kai-shek, China's leader, and gain full command of all Chinese armed forces. He was able to convince General George Marshall to have President Franklin D. Roosevelt send an ultimatum to Chiang threatening to end all American aid unless Chiang "at once" placed Stilwell "in unrestricted command of all your forces."[18]

An exultant Stilwell immediately delivered this letter to Chiang despite pleas from Patrick Hurley, Roosevelt's special envoy in China, to delay delivering the message and work on a deal that would achieve Stilwell's aim in a manner more acceptable to Chiang.[19] Seeing this act as a move toward the complete subjugation of China, a defiant Chiang gave a formal reply in which he said that Stilwell must be replaced immediately and he would welcome any other qualified U.S. general to fill Stilwell's position.[20][21] As a result, Stilwell was replaced as Chief of Staff to Chiang Kai-shek and commander of the U.S. Forces, China Theater (USFCT) by Major General Albert Wedemeyer. Stilwell's other command responsibilities in the China Burma India Theater were divided up and allocated to other officers.

Although Chiang was successful in removing Stilwell, the public relations damage suffered by his Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) regime was irreparable. Right before Stilwell's departure, New York Times drama critic-turned-war correspondent Brooks Atkinson interviewed him in Chungking and wrote:

The decision to relieve General Stilwell represents the political triumph of a moribund, anti-democratic regime that is more concerned with maintaining its political supremacy than in driving the Japanese out of China. The Chinese Communists... have good armies that they are claiming to be fighting guerrilla warfare against the Japanese in North China—actually they are covertly or even overtly building themselves up to fight Generalissimo's government forces... The Generalissimo [Chiang Kai-shek] naturally regards these armies as the chief threat to the country and his supremacy... has seen no need to make sincere attempt to arrange at least a truce with them for the duration of the war... No diplomatic genius could have overcome the Generalissimo's basic unwillingness to risk his armies in battle with the Japanese.[22]

Atkinson, who had visited Mao Zedong in the communist capital of Yenan, saw his Communist Chinese forces as a democratic movement (after Atkinson visited Mao, his article on his visit was titled Yenan: A Chinese Wonderland City), and the Nationalists in turn as hopelessly reactionary and corrupt. This view was shared by many U.S. journalists in China at the time, but due to pro-Chiang Allied press censorship, it was not as well known to their readers until Stilwell's recall and the ensuing anti-Chiang coverage forced it into the open.[23]

The Japanese successes in Operation Ichi-Go had a limited effect on the war. The U.S. could still bomb the Japanese homeland from Saipan and other Pacific bases. In the territories seized, Japanese forces controlled only the cities, not their surrounding countryside. The increased size of the occupied territory also thinned out the Japanese lines. A great majority of the Chinese forces were able to retreat out of the area, and later come back to attack Japanese positions. As a result, future Japanese attempts to fight into Sichuan, such as in the Battle of West Hunan, ended in failure. All in all, Japan was not any closer in defeating China after this operation, and the constant defeats the Japanese suffered in the Pacific meant that Japan never got the time and resources needed to achieve final victory over China. The Japanese suffered 11,742 KIAs by mid-November, and the number of soldiers that died of illness was more than twice this.[24][25][26] The total death toll was about 100,000 by the end of 1944.[5]

Operation Ichi-go created a great sense of social confusion in the areas of China that it affected. Chinese Communist guerrillas were able to exploit this confusion to gain influence and control of greater areas of the countryside in the aftermath of Ichi-go.[27]

In popular culture

The 1958 novel The Mountain Road, by Theodore White, a Time magazine correspondent in China at the time of the offensive, was based on an interview with former OSS Major Frank Gleason, who led a demolition group of American soldiers during the offensive that were charged with blowing up anything left behind in the retreat that might be of use to Japan. His group ultimately destroyed over 150 bridges and 50,000 tons of munitions, helping slow the Japanese advance. In 1960, it was adapted into a film starring James Stewart and Lisa Lu, noteworthy for being one of Stewart's only war films and the only one where he plays a soldier, as he was opposed to war films due to their inaccuracy. It is generally believed he made an exception for this film because it was anti-war.

References

- Davison, John The Pacific War: Day By Day, pg. 37, 106

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2015-11-16.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hastings, Retribution pg. 210

- Hsiung, China's Bitter Victory pgs. 162-165

- 記者が語りつぐ戦争 16 中国慰霊 読売新聞社 (1983/2) P187

- "Operation Ichi-Go" Archived 2015-11-17 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 16 Nov. 2015

- Hsiung, China's Bitter Victory pg. 165

- Cox, 1980 pp. 2 Retrieved 9 March 2016

- Sandler, Stanley. "World War II in the Pacific: an Encyclopedia" p. 431

- The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II: China Defensive, pg. 21

- Hsiung, China's Bitter Victory pgs. 162-166

- Mitter, Rana (2014). China's War with Japan, 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival. Penguin Books. pp. 323–324. ISBN 978-0-141-03145-3.

- Mitter, Rana (2014). China's War with Japan, 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival. Penguin Books. pp. 271–272, 326. ISBN 978-0-141-03145-3.

- Mitter, Rana (2014). China's War with Japan, 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival. Penguin Books. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-141-03145-3.

- Mitter, Rana (2014). China's War with Japan, 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival. Penguin Books. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-141-03145-3.

- Mitter, Rana (2014). China's War with Japan, 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival. Penguin Books. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-141-03145-3.

- Mitter, Rana (2014). China's War with Japan, 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival. Penguin Books. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-141-03145-3.

- Romanus and Sunderland, Stilwell's Command Problem, p.446–447

- Lohbeck, Hurley, p.292

- Lohbeck, Hurley, p.298

- Romanus and Sunderland, Stilwell's Command Problem, p.452

- "Crisis". Time magazine quoting The New York Times. 1944-11-13. Retrieved 2007-03-02. Italic or bold markup not allowed in:

|magazine=(help) - Knightley, Phillip (2004). The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero and Myth-Maker from the Crimea to Iraq (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-8018-8030-8.

- http://d.hatena.ne.jp/Apeman/20070710/p1

- Until mid-November, IJA had a illness toll of 66,000,and a field hospital had taken in 6164 soldiers, 2,281 of which died due to malnutrition 餓死した英霊たち P116

- In 1944, twice as many Japanese soldiers died of illness as KIA

- China at War: An Encyclopedia. Ed. Li Xiaobing. United States of America: ABC-CLIO. 2012. ISBN 978-1-59884-415-3. Retrieved May 21, 2012. p.163.

Bibliography

- Mitter, Rana, China's War with Japan, 1937-1945: The Struggle for Survival, Penguin Books (2014), ISBN 978-0-141-03145-3

Further reading

- Sherry, Mark D. China Defensive. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-38.