Battle of Buxar

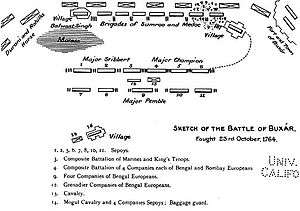

The Battle of Buxar was fought on 22 October 1764, between the forces under the command of the British East India Company, led by Hector Munro, and the combined armies of Mir Qasim, the Nawab of Bengal till 1763. Mir Jafar was made the Nawab of Bengal for a second time in 1763 by the Company, just after the battle. After being defeated in 4 battles in Katwa, Giria and Udaynala, the Nawab of Awadh Shuja-ud-Daula and the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II, accompanied by Raja Balwant Singh of Kashi made an alliance with Mir Qasim.[4] The battle was fought at Buxar, a "small fortified town" within the territory of Bihar, located on the banks of the Ganga river about 130 kilometres (81 mi) west of Patna; it was a decisive victory for the British East India Company. The war was brought to an end by the Treaty of Allahabad in 1765.

| Battle of Buxar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Bengal War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

40,000 140 cannons |

7,072 30 cannons | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Disputed British claim:[2] 2,000 killed | 1,000 killed, wounded or missing[2][3] | ||||||

Battle

The British army engaged in the fighting numbered 7,072[5] comprising 859 British, 5,297 Indian sepoys and 918 Indian cavalry. The alliance army's numbers were estimated to be over 40,000. The British East India Company was at war with the alliance of Indian states that was composed of Bengal, Awadh, and the Mughal Empire.[6] This consisted of 40,000 men and was defeated by a British army comprising 10,000 men. The Nawabs had virtually lost their military power after the battle of Buxar.

The lack of basic co-ordination among the three disparate allies was responsible for their decisive defeat.

Mirza Najaf Khan commanded the right flank of the Mughal imperial army and was the first to advance his forces against Major Hector Munro at daybreak; the British lines formed within twenty minutes and reversed the advance of the Mughals. According to the British, Durrani and Rohilla cavalry were also present and fought during the battle in various skirmishes. But by midday, the battle was over and Shuja-ud-Daula blew up large tumbrils and three massive magazines of gunpowder.

Munro divided his army into various columns and particularly pursued the Mughal Grand Vizier Shuja-ud-Daula the Nawab of Awadh, who responded by blowing up his boat-bridge after crossing the river, thus abandoning the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II and members of his own regiment. Mir Qasim also fled with his 3 million rupees worth of Gemstones and later died in poverty in 1777. Mirza Najaf Khan reorganised formations around Shah Alam II, who retreated and then chose to negotiate with the victorious British.

Historian John William Fortescue claimed that the British casualties totalled 847: 39 killed and 64 wounded from the European regiments and 250 killed, 435 wounded and 85 missing from the East India Company's sepoys.[2] He also claimed that the three Indian allies suffered 2,000 dead and that many more were wounded.[2] Another source says that there were 69 European and 664 sepoy casualties on the British side and 6,000 casualties on the Mughal side.[3] The victors captured 133 pieces of artillery and over 1 million rupees of cash. Immediately after the battle Munro decided to assist the Marathas, who were described as a "warlike race", well known for their relentless and unwavering hatred towards the Mughal Empire and its Nawabs and Mysore.

Immediately After

The British victory at Buxar had "at one fell swoop", disposed of the three main scions of Mughal power in Upper India. Mir Kasim [Qasim] disappeared into an impoverished obscurity. Shah Alam realigned himself with the British, and Shah Shuja [Shuja-ud-Daula] fled west hotly pursued by the victors. The whole Ganges valley lay at the Company's mercy; Shah Shuja eventually surrendered; henceforth Company troops became the power-brokers throughout Oudh as well as Bihar.[7]

Long Term Aftermath

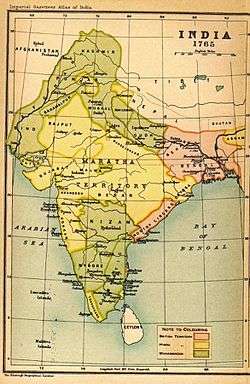

This battle altered the future path for India. The British had been interested in coastal areas including Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta. This battle along with the battles of Palasi and the Anglo-French wars in Carnatic began a British conquest of India. By 1765 the British were essentially ruling Bihar and Bengal. The Nawab of Awadh started to become dependent on them and soon became the Nawab of Carnatic. There is still some historical tension between Britain and India. Much of this tension was created in the events leading up to the war which included misuse of Farman and Dastak by the British which challenged the authority of Mir Qasim, pressure and force applied to Indian vendors, peasants, merchants, and artisans to sell their products at ridiculously low prices, begin a trend of bribery, an abolition of all duties on internal trade from the British, and also British abuse to trade ethics and challenged Nawab authority. In that same year, there was a treaty signed after the battle by Shah Alam and Shuja-ud-daulah. These treaties were signed at Allahabad. As stated before, the English Company had direct rule over Odisha, Bihar, and Bengal; it was because of this signed treaty. Because of this treaty, the British Company was then allowed to collect revenue from the three territories. Following this the Nawab of Awadh went under British troop protection. This could be seen as either a threat, or the strengthening of these territories. In agreement to all of this, a deal was included which required the East India Company to pay an amount of 26 Lakh Rupees to the Mughal Empire every year. After all of these events, unsurprisingly, the British stopped paying this after a while. The British troops further established their superiority by essentially doing whatever it was they pleased; the East India Company promised the Nawab protection and security from any enemy or invader in exchange for a certain sum of money but they were required to pay for their service. After some time, the British Company made huge profits from extortion. One particular case that was memorable was when the son of Mir Jafar took the position of his father as the new Nawab and the British extorted large sums of money from him. This battle was more of a nail in the coffin after the British won the Battle of Plassey. Much like the bribery that happened during the Battle of Plassey, bribery was a very powerful and used tactic for the British. But even then, the end result would always be the British having their way and much more to the point where the initial receivers of the bribes were stripped of more than they received. Today, there is a monument in West Bengal commemorating the Battle of Plassey. Victory for the British in the battle of Buxar delivered promise for their future plans that involved control over Bihar and Bengal, that would further help them to impose their power and authority on the Indian subcontinent.[6]

Gallery

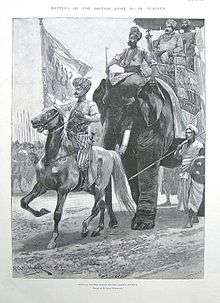

The Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II, as a prisoner of the British East India Company, 1781

The Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II, as a prisoner of the British East India Company, 1781 The Nawab of Bengal, Mir Qasim

The Nawab of Bengal, Mir Qasim Shuja-ud-Daula served as the leading Nawab Vizier of the Mughal Empire, he was a lifelong of Shah Alam II.

Shuja-ud-Daula served as the leading Nawab Vizier of the Mughal Empire, he was a lifelong of Shah Alam II. Mirza Najaf Khan Baloch, the commander-in-chief of the Mughal Army.

Mirza Najaf Khan Baloch, the commander-in-chief of the Mughal Army. Political map of the Indian Subcontinent in the year 1765.

Political map of the Indian Subcontinent in the year 1765.

See also

References

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (2009). History Of The Freedom Movement In India (1857-1947). New Age International. p. 2. ISBN 9788122425765.

- John William (29 February 2004). Fortescue's History of the British Army -. 2. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-715-5.

- Black, Jeremy (28 March 1996). Wyse, Liz (ed.). The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: Renaissance to Revolution, 1492-1792. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-521-47033-9.

- Parshotam Mehra (1985). A Dictionary of Modern History (1707–1947). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-561552-2.

- Cust, Edward (1858). Annals of the Wars of the Eighteenth Century: 1760–1783. III. London: Mitchell's Military Library. p. 113.

- Bunting, Tony. "Battle of Buxar". Britannica.

- Keay, John (8 July 2010). The Honourable Company (Paperback ed.). London: HarperCollins UK. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-00-739554-5.