Art film

An art film is typically a serious, independent film, aimed at a niche market rather than a mass market audience.[1] It is "intended to be a serious, artistic work, often experimental and not designed for mass appeal",[2] "made primarily for aesthetic reasons rather than commercial profit",[3] and contains "unconventional or highly symbolic content".[4]

_by_Erling_Mandelmann.jpg)

Film critics and film studies scholars typically define an art film as possessing "formal qualities that mark them as different from mainstream Hollywood films".[5] These qualities can include (among other elements): a sense of social realism; an emphasis on the authorial expressiveness of the director; and a focus on the thoughts, dreams, or motivations of characters, as opposed to the unfolding of a clear, goal-driven story. Film scholar David Bordwell describes art cinema as "a film genre, with its own distinct conventions".[6]

Art film producers usually present their films at special theaters (repertory cinemas or, in the U.S., art-house cinemas) and at film festivals. The term art film is much more widely used in North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia, compared to the mainland Europe, where the terms auteur films and national cinema (e.g. German national cinema) are used instead. Since they are aimed at small, niche-market audiences, art films rarely acquire the financial backing that would permit large production budgets associated with widely released blockbuster films. Art film directors make up for these constraints by creating a different type of film, one that typically uses lesser-known film actors (or even amateur actors), and modest sets to make films that focus much more on developing ideas, exploring new narrative techniques, and attempting new film-making conventions.

Such films contrast sharply with mainstream blockbuster films, which are geared more towards linear storytelling and entertainment. Film critic Roger Ebert called Chungking Express, a critically acclaimed 1994 art film, "largely a cerebral experience" that one enjoys "because of what you know about film".[7] For promotion, art films rely on the publicity generated from film critics' reviews; discussion of the film by arts columnists, commentators, and bloggers; and word-of-mouth promotion by audience members. Since art films have small initial investment costs, they only need to appeal to a small portion of mainstream audiences to become financially viable.

History

Antecedents: 1910–1920s

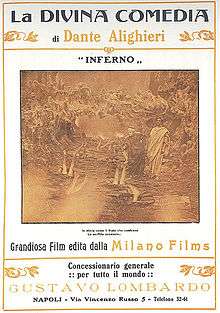

The forerunners of art films include Italian silent film L'Inferno (1911), D. W. Griffith's Intolerance (1916) and the works of Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, who influenced the development of European cinema movements for decades.[8][9][10] Eisenstein's film Battleship Potemkin (1925) was a revolutionary propaganda film he used to test his theories of using film editing to produce the greatest emotional response from an audience. The international critical renown that Eisenstein garnered from this film enabled him to direct October as part of a grand 10th anniversary celebration of the October Revolution of 1917. He later directed The General Line in 1929.

Art films were also influenced by films by Spanish avant-garde creators, such as Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí (who made L'Age d'Or in 1930), and by the French playwright and filmmaker Jean Cocteau, whose 1930's avant-garde film The Blood of a Poet uses oneiric images throughout, including spinning wire models of a human head and rotating double-sided masks. In the 1920s, film societies began advocating the notion that films could be divided into "entertainment cinema directed towards a mass audience and a serious art cinema aimed at an intellectual audience". In England, Alfred Hitchcock and Ivor Montagu formed a film society and imported films they thought were "artistic achievements", such as "Soviet films of dialectical montage, and the expressionist films of the Universum Film A.G. (UFA) studios in Germany".[8]

Cinéma pur, a French avant-garde film movement in the 1920s and 1930s, also influenced the development of the idea of art film. The cinema pur film movement included several notable Dada artists. The Dadaists used film to transcend narrative storytelling conventions, bourgeois traditions, and conventional Aristotelian notions of time and space by creating a flexible montage of time and space.

The cinema pur movement was influenced by German "absolute" filmmakers such as Hans Richter, Walter Ruttmann and Viking Eggeling. Richter falsely claimed that his 1921 film Rhythmus 21 was the first abstract film ever created. In fact, he was preceded by the Italian Futurists Bruno Corra and Arnaldo Ginna between 1911 and 1912[11] (as reported in the Futurist Manifesto of Cinema[11]), as well as by fellow German artist Walter Ruttmann, who produced Lichtspiel Opus 1 in 1920. Nevertheless, Richter's film Rhythmus 21 is considered an important early abstract film.

1930s–1950s

In the 1930s and 1940s, Hollywood films could be divided into the artistic aspirations of literary adaptations like John Ford's The Informer (1935) and Eugene O'Neill's The Long Voyage Home (1940), and the money-making "popular-genre films" such as gangster thrillers. William Siska argues that Italian neorealist films from the mid-to-late 1940s, such as Open City (1945), Paisa (1946), and Bicycle Thieves can be deemed as another "conscious art film movement".[8]

In the late 1940s, the U.S. public's perception that Italian neorealist films and other serious European fare were different from mainstream Hollywood films was reinforced by the development of "arthouse cinemas" in major U.S. cities and college towns. After the Second World War, "...a growing segment of the American film going public was wearying of mainstream Hollywood films", and they went to the newly created art-film theaters to see "alternatives to the films playing in main-street movie palaces".[5] Films shown in these art cinemas included "British, foreign-language, and independent American films, as well as documentaries and revivals of Hollywood classics". Films such as Rossellini's Open City and Mackendrick's Tight Little Island (Whisky Galore!), Bicycle Thieves and The Red Shoes were shown to substantial U.S. audiences.[5]

In the late 1950s, French filmmakers began to produce films that were influenced by Italian Neorealism[12] and classical Hollywood cinema,[12] a style that critics called the French New Wave. Although never a formally organized movement, New Wave filmmakers were linked by their self-conscious rejection of classical cinematic form and their spirit of youthful iconoclasm, and their films are an example of European art cinema.[13] Many also engaged in their work with the social and political upheavals of the era, making their radical experiments with editing, visual style and narrative part of a general break with the conservative paradigm. Some of the most prominent pioneers among the group, including François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, and Jacques Rivette, began as critics for the film magazine Cahiers du cinéma. Auteur theory holds that the director is the "author" of his films, with a personal signature visible from film to film.

1960s–1970s

The French New Wave movement continued into the 1960s. During the 1960s, the term "art film" began to be much more widely used in the United States than in Europe. In the U.S., the term is often defined very broadly to include foreign-language (non-English) "auteur" films, independent films, experimental films, documentaries and short films. In the 1960s, "art film" became a euphemism in the U.S. for racy Italian and French B-movies. By the 1970s, the term was used to describe sexually explicit European films with artistic structure such as the Swedish film I Am Curious (Yellow). In the U.S., the term "art film" may refer to films by modern American artists, including Andy Warhol with his 1969 film Blue Movie,[14][15][16] but is sometimes used very loosely to refer to the broad range of films shown in repertory theaters or "art house cinemas". With this approach, a broad range of films, such as a 1960s Hitchcock film, a 1970s experimental underground film, a European auteur film, a U.S. "independent" film, and even a mainstream foreign-language film (with subtitles) might all fall under the rubric of "art house films".

1980s–2000s

By the 1980s and 1990s, the term "art film" became conflated with "independent film" in the U.S., which shares many of the same stylistic traits. Companies such as Miramax Films distributed independent films that were deemed commercially viable. When major motion-picture studios noted the niche appeal of independent films, they created special divisions dedicated to non-mainstream fare, such as the Fox Searchlight Pictures division of Twentieth Century Fox, the Focus Features division of Universal, the Sony Pictures Classics division of Sony Pictures Entertainment, and the Paramount Vantage division of Paramount. Film critics have debated whether films from these divisions can be considered "independent films", given they have financial backing from major studios.

In 2007, Professor Camille Paglia argued in her article "Art movies: R.I.P." that "[a]side from Francis Ford Coppola's Godfather series, with its deft flashbacks and gritty social realism, ...[there is not]... a single film produced over the past 35 years that is arguably of equal philosophical weight or virtuosity of execution to Bergman's The Seventh Seal or Persona". Paglia states that young people from the 2000s do not "have patience for the long, slow take that deep-think European directors once specialized in", an approach which gave "luxurious scrutiny of the tiniest facial expressions or the chilly sweep of a sterile room or bleak landscape".[17]

According to director, producer, and distributor Roger Corman, the "1950s and 1960s was the time of the art film's greatest influence. After that, the influence waned. Hollywood absorbed the lessons of the European films and incorporated those lessons into their films." Corman states that "viewers could see something of the essence of the European art cinema in the Hollywood movies of the seventies... [and so], art film, which was never just a matter of European cinema, increasingly became an actual world cinema—albeit one that struggled to gain wide recognition". Corman notes that, "Hollywood itself has expanded, radically, its aesthetic range... because the range of subjects at hand has expanded to include the very conditions of image-making, of movie production, of the new and prismatic media-mediated experience of modernity. There's a new audience that has learned about art films at the video store." Corman states that "there is currently the possibility of a rebirth" of American art film.[18]

Deviations from mainstream film norms

Film scholar David Bordwell outlined the academic definition of "art film" in a 1979 article entitled "The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice", which contrasts art films with the mainstream films of classical Hollywood cinema. Mainstream Hollywood-style films use a clear narrative form to organize the film into a series of "causally related events taking place in space and time", with every scene driving towards a goal. The plot of mainstream films is driven by a well-defined protagonist, fleshed out with clear characters, and strengthened with "question-and-answer logic, problem-solving routines, [and] deadline plot structures". The film is then tied together with fast pacing, a musical soundtrack to cue the appropriate audience emotions, and tight, seamless editing.[19]

In contrast, Bordwell states that "the art cinema motivates its narrative by two principles: realism and authorial expressiveness". Art films deviate from the mainstream "classical" norms of film making in that they typically deal with more episodic narrative structures with a "loosening of the chain of cause and effect".[19]

Mainstream films also deal with moral dilemmas or identity crises, but these issues are usually resolved by the end of the film. In art films, the dilemmas are probed and investigated in a pensive fashion, but usually without a clear resolution at the end of the film.[20]

The story in an art film often has a secondary role to character development and exploration of ideas through lengthy sequences of dialogue. If an art film has a story, it is usually a drifting sequence of vaguely defined or ambiguous episodes. There may be unexplained gaps in the film, deliberately unclear sequences, or extraneous sequences that are not related to previous scenes, which force the viewer to subjectively make their own interpretation of the film's message. Art films often "bear the marks of a distinctive visual style" and the authorial approach of the director.[21] An art cinema film often refuses to provide a "readily answered conclusion", instead putting to the cinema viewer the task of thinking about "how is the story being told? Why tell the story in this way?"[22]

Bordwell claims that "art cinema itself is a [film] genre, with its own distinct conventions".[6] Film theorist Robert Stam also argues that "art film" is a film genre. He claims that a film is considered to be an art film based on artistic status in the same way film genres can be based on aspects of films such as their budgets (blockbuster films or B-movies) or their star performers (Adam Sandler films).[23]

Art film and film criticism

There are scholars who point out that mass market films such as those produced in Hollywood appeal to a less discerning audience.[24] This group then turns to film critics as a cultural elite that can help steer them towards films that are more thoughtful and of a higher quality. To bridge the disconnect between popular taste and high culture, these film critics are expected to explain unfamiliar concepts and make them appealing to cultivate a more discerning movie-going public. For example, a film critic can help the audience—through his reviews—think seriously about films by providing the terms of analysis of these art films.[25] Adopting an artistic framework of film analysis and review, these film critics provide viewers with a different way to appreciate what they are watching. So when controversial themes are explored, the public will not immediately dismiss or attack the movie where they are informed by critics of the film's value such as how it depicts realism. Here, art theaters or art houses that exhibit art films are seen as "sites of cultural enlightenment" that draw critics and intellectual audiences alike. It serves as a place where these critics can experience culture and an artistic atmosphere where they can draw insights and material.

Timeline of notable films

The following list is a small, partial sample of films with "art film" qualities, compiled to give a general sense of what directors and films are considered to have "art film" characteristics. The films in this list demonstrate one or more of the characteristics of art films: a serious, non-commercial, or independently made film that is not aimed at a mass audience. Some of the films on this list are also considered to be "auteur" films, independent films, or experimental films. In some cases, critics disagree over whether a film is mainstream or not. For example, while some critics called Gus Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho (1991) an "exercise in film experimentation" of "high artistic quality",[26] The Washington Post called it an ambitious mainstream film.[27] Some films on this list have most of these characteristics; other films are commercially made films, produced by mainstream studios, that nevertheless bear the hallmarks of a director's "auteur" style, or which have an experimental character. The films on this list are notable either because they won major awards or critical praise from influential film critics, or because they introduced an innovative narrative or film-making technique.

1920s–1940s

In the 1920s and 1930s, filmmakers did not set out to make "art films", and film critics did not use the term "art film". However, there were films that had sophisticated aesthetic objectives, such as Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) and Vampyr (1932), surrealist films such as Luis Buñuel's Un chien andalou (1929) and L'Âge d'Or (1930), or even films dealing with political and current-event relevance such as Sergei Eisenstein's famed and influential masterpiece Battleship Potemkin. The U.S. film Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927) by German Expressionist director F. W. Murnau uses distorted art design and groundbreaking cinematography to create an exaggerated, fairy-tale-like world rich with symbolism and imagery. Jean Renoir's film The Rules of the Game (1939) is a comedy of manners that transcends the conventions of its genre by creating a biting and tragic satire of French upper-class society in the years before WWII; a poll of critics from Sight & Sound ranked it as the fourth greatest film ever, placing it behind Vertigo, Citizen Kane and Tokyo Story.[28]

_English_Poster.png)

Some of these early, artistically-oriented films were financed by wealthy individuals rather than film companies, particularly in cases where the content of the film was controversial or unlikely to attract an audience. In the late 1940s, UK director Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger made The Red Shoes (1948), a film about ballet, which stood out from mainstream-genre films of the era. In 1945, David Lean directed Brief Encounter, an adaptation of Noël Coward's play Still Life, which observes a passionate love affair between an upper-class man and a middle-class woman amidst the social and economic issues that Britain faced at the time.

1950s

In the 1950s, some of the well-known films with artistic sensibilities include La Strada (1954), a film about a young woman who is forced to go to work for a cruel and inhumane circus performer to support her family, and eventually comes to terms with her situation; Carl Theodor Dreyer's Ordet (1955), centering on a family with a lack of faith, but with a son who believes that he is Jesus Christ and convinced that he is capable of performing miracles; Federico Fellini's Nights of Cabiria (1957), which deals with a prostitute's failed attempts to find love, her suffering and rejection; Wild Strawberries (1957), by Ingmar Bergman, whose narrative concerns an elderly medical doctor, who is also a professor, whose nightmares lead him to re-evaluate his life; and The 400 Blows (1959) by François Truffaut, whose main character is a young man trying to come of age despite abuse from his parents, schoolteachers, and society. In Poland, the Khrushchev Thaw permitted some relaxation of the regime's cultural policies, and productions such as A Generation, Kanal, Ashes and Diamonds, Lotna (1954–1959), all directed by Andrzej Wajda, showed the Polish Film School style.

Asia

In India, there was an art-film movement in Bengali cinema known as "Parallel Cinema" or "Indian New Wave". This was an alternative to the mainstream commercial cinema known for its serious content, realism and naturalism, with a keen eye on the social-political climate of the times. This movement is distinct from mainstream Bollywood cinema and began around the same time as French and Japanese New Wave. The most influential filmmakers involved in this movement were Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak. Some of the most internationally acclaimed films made in the period were The Apu Trilogy (1955–1959), a trio of films that tell the story of a poor country boy's growth to adulthood, and Satyajit Ray's Distant Thunder (1973), which tells the story of a farmer during a famine in Bengal.[29][30] Other acclaimed Bengali filmmakers involved in this movement include Rituparno Ghosh, Aparna Sen and Goutam Ghose.

Japanese filmmakers produced a number of films that broke with convention. Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon (1950), the first Japanese film to be widely screened in the West, depicts four witnesses' contradictory accounts of a rape and murder. In 1952, Kurosawa directed Ikiru, a film about a Tokyo bureaucrat struggling to find a meaning for his life. Tokyo Story (1953), by Yasujirō Ozu, explores social changes of the era by telling the story of an aging couple who travel to Tokyo to visit their grown children, but find the children are too self-absorbed to spend much time with them. Seven Samurai (1954), by Kurosawa, tells the story of a farming village that hires seven master-less samurais to combat bandits. Fires on the Plain (1959), by Kon Ichikawa, explores the Japanese experience in World War II by depicting a sick Japanese soldier struggling to stay alive. Ugetsu (1953), by Kenji Mizoguchi, is a ghost story set in the late 16th century, which tells the story of peasants whose village is in the path of an advancing army. A year later, Mizoguchi directed Sansho the Bailiff (1954), which tells the story of two aristocratic children sold into slavery; in addition to dealing with serious themes such as the loss of freedom, the film features beautiful images and long, complicated shots.

1960s

The 1960s was an important period in art film, with the release of a number of groundbreaking films giving rise to the European art cinema. Jean-Luc Godard's À bout de souffle (Breathless) (1960) used innovative visual and editing techniques such as jump cuts and hand-held camera work. Godard, a leading figure of the French New Wave, would continue to make innovative films throughout the decade, proposing a whole new style of film-making. Following the success of Breathless, Goddard made two more very influential films, Contempt and Pierrot le fou, in 1963 and 1965 respectively. Jules et Jim, by François Truffaut, deconstructed a complex relationship of three individuals through innovative screenwriting, editing, and camera techniques. Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni helped revolutionize filmmaking with such films as La Notte (1961), a complex examination of a failed marriage that dealt with issues such as anomie and sterility; Eclipse (1962), about a young woman who is unable to form a solid relationship with her boyfriend because of his materialistic nature; Red Desert (1964), his first color film, which deals with the need to adapt to the modern world; and Blowup (1966), his first English-language film, which examines issues of perception and reality as it follows a young photographer's attempt to discover whether he had photographed a murder.

Swedish director Ingmar Bergman began the 1960s with chamber pieces such as Winter Light (1963) and The Silence (1963), which deal with such themes as emotional isolation and a lack of communication. His films from the second half of the decade, such as Persona (1966), Shame (1968), and A Passion (1969), deal with the idea of film as an artifice. The intellectual and visually expressive films of Tadeusz Konwicki, such as All Souls' Day (Zaduszki, 1961) and Salto (1962), inspired discussions about war and raised existential questions on behalf of their everyman protagonists.

Federico Fellini's La Dolce Vita (1960) depicts a succession of nights and dawns in Rome as witnessed by a cynical journalist. In 1963, Fellini made 8½, an exploration of creative, marital and spiritual difficulties, filmed in black-and-white by cinematographer Gianni di Venanzo. The 1961 film Last Year at Marienbad by director Alain Resnais examines perception and reality, using grand tracking shots that became widely influential. Robert Bresson's Au Hasard Balthazar (1966) and Mouchette (1967) are notable for their naturalistic, elliptical style. Spanish director Luis Buñuel also contributed heavily to the art of film with shocking, surrealist satires such as Viridiana (1961) and The Exterminating Angel (1962).

Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky's film Andrei Rublev (1966) is a portrait of the medieval Russian icon painter of the same name. The film is also about artistic freedom and the possibility and necessity of making art for, and in the face of, a repressive authority. A cut version of the film was shown at the 1969 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the FIPRESCI prize.[31] At the end of the decade, Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) wowed audiences with its scientific realism, pioneering use of special effects, and unusual visual imagery. In 1969, Andy Warhol released Blue Movie, the first adult art film depicting explicit sex to receive wide theatrical release in the United States.[14][15][16] According to Warhol, Blue Movie was a major influence in the making of Last Tango in Paris, an internationally controversial erotic art film, directed by Bernardo Bertolucci and released a few years after Blue Movie was made.[16] In Soviet Georgia, Sergei Parajanov's The Color of Pomegranates, in which Georgian actress Sofiko Chiaureli plays five different characters, was banned by Soviet authorities, unavailable in the West for a long period, and praised by critic Mikhail Vartanov as "revolutionary";[32] and in the early 1980s, Les Cahiers du Cinéma placed the film in its top 10 list.[33] In 1967, in Soviet Georgia, influential Georgian film director Tengiz Abuladze directed Vedreba (Entreaty), which was based on the motifs of Vaja-Pshavela's literary works, where story is told in a poetic narrative style, full of symbolic scenes with philosophical meanings. In Iran, Dariush Mehrjui's The Cow (1969), about a man who becomes insane after the death of his beloved cow, sparked the new wave of Iranian cinema.

1970s

In the early 1970s, directors shocked audiences with violent films such as A Clockwork Orange (1971), Stanley Kubrick's brutal exploration of futuristic youth gangs, and Last Tango in Paris (1972), Bernardo Bertolucci's taboo-breaking, sexually-explicit and controversial film. At the same time, other directors made more introspective films, such as Andrei Tarkovsky's meditative science fiction film Solaris (1972), supposedly intended as a Soviet riposte to 2001. In 1975 and 1979 respectively, Tarkovsky directed two other films, which garnered critical acclaim overseas: The Mirror and Stalker. Terrence Malick, who directed Badlands (1973) and Days of Heaven (1978) shared many traits with Tarkovsky, such as his long, lingering shots of natural beauty, evocative imagery, and poetic narrative style.

Another feature of 1970s art films was the return to prominence of bizarre characters and imagery, which abound in the tormented, obsessed title character in German New Wave director Werner Herzog's Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1973), and in cult films such as Alejandro Jodorowsky's psychedelic The Holy Mountain (1973) about a thief and an alchemist seeking the mythical Lotus Island.[34] The film Taxi Driver (1976), by Martin Scorsese, continues the themes that A Clockwork Orange explored: an alienated population living in a violent, decaying society. The gritty violence and seething rage of Scorsese's film contrasts other films released in the same period, such as David Lynch's dreamlike, surreal and industrial black and white classic Eraserhead (1977).[35] In 1974, John Cassavetes offered a sharp commentary on American blue-collar life in A Woman Under the Influence, which features an eccentric housewife slowly descending into madness.

Also in the 1970s, Radley Metzger directed several adult art films, such as Barbara Broadcast (1977), which presented a surrealistic "Buñellian" atmosphere,[36] and The Opening of Misty Beethoven (1976), based on the play Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw (and its derivative, My Fair Lady), which was considered, according to award-winning author Toni Bentley, to be the "crown jewel" of the Golden Age of Porn,[37][38] an era in modern American culture that was inaugurated by the release of Andy Warhol's Blue Movie (1969) and featured the phenomenon of "porno chic"[39][40] in which adult erotic films began to obtain wide release, were publicly discussed by celebrities (such as Johnny Carson and Bob Hope)[41] and taken seriously by film critics (such as Roger Ebert).[42][43]

1980s

In 1980, director Martin Scorsese gave audiences, who had become used to the escapist blockbuster adventures of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, the gritty, harsh realism of his film Raging Bull. In this film, actor Robert De Niro took method acting to an extreme to portray a boxer's decline from a prizewinning young fighter to an overweight, "has-been" nightclub owner. Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (1982) could also be seen as a science fiction art film, along with 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Blade Runner explores themes of existentialism, or what it means to be human. A box-office failure, the film became popular on the arthouse circuit as a cult oddity after the release of a "director's cut" became successful via VHS home video. In the middle of the decade, Japanese director Akira Kurosawa used realism to portray the brutal, bloody violence of Japanese samurai warfare of the 16th century in Ran (1985). Ran followed the plot of King Lear, in which an elderly king is betrayed by his children. Sergio Leone also contrasted brutal violence with emotional substance in his epic tale of mobster life in Once Upon a Time in America.

Other directors in the 1980s chose a more intellectual path, exploring philosophical and ethical issues. Andrzej Wajda's Man of Iron (1981), a critique of the Polish communist government, won the 1981 Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Another Polish director, Krzysztof Kieślowski, made The Decalogue for television in 1988, a film series that explores ethical issues and moral puzzles. Two of these films were released theatrically as A Short Film About Love and A Short Film About Killing. In 1989, Woody Allen made, in the words of New York Times critic Vincent Canby, his most "securely serious and funny film to date", Crimes and Misdemeanors, which involves multiple stories of people who are trying to find moral and spiritual simplicity while facing dire issues and thoughts surrounding the choices they make. French director Louis Malle chose another moral path to explore with the dramatization of his real-life childhood experiences in Au revoir, les enfants, which depicts the occupying Nazi government's deportation of French Jews to concentration camps during World War II.

Another critically praised art film from this era, Wim Wenders's road movie Paris, Texas (1984), also won the Palme d'Or.[44][45]

Kieślowski was not the only director to transcend the distinction between the cinema and television. Ingmar Bergman made Fanny and Alexander (1982), which was shown on television in an extended five-hour version. In the United Kingdom, Channel 4, a new television channel, financed, in whole or in part, many films released theatrically through its Film 4 subsidiary. Wim Wenders offered another approach to life from a spiritual standpoint in his 1987 film Wings of Desire, a depiction of a "fallen angel" who lives among men, which won the Best Director Award at the Cannes Film Festival. In 1982, experimental director Godfrey Reggio released Koyaanisqatsi, a film without dialogue, which emphasizes cinematography and philosophical ideology. It consists primarily of slow motion and time-lapse cinematography of cities and natural landscapes, which results in a visual tone poem.[46]

Another approach used by directors in the 1980s was to create bizarre, surreal alternative worlds. Martin Scorsese's After Hours (1985) is a comedy-thriller that depicts a man's baffling adventures in a surreal nighttime world of chance encounters with mysterious characters. David Lynch's Blue Velvet (1986), a film noir-style thriller-mystery filled with symbolism and metaphors about polarized worlds and inhabited by distorted characters who are hidden in the seamy underworld of a small town, became surprisingly successful considering its highly disturbing subject matter. Peter Greenaway's The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989) is a fantasy/black comedy about cannibalism and extreme violence with an intellectual theme: a critique of "elite culture" in Thatcherian Britain.

According to Raphaël Bassan, in his article "The Angel: Un météore dans le ciel de l'animation",[47] Patrick Bokanowski's The Angel, shown at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival, can be considered the beginning of contemporary animation. The characters' masks erase all human personality and give the impression of total control over the "matter" of the image and its optical composition, using distorted areas, obscure visions, metamorphoses, and synthetic objects.

1990s

In the 1990s, directors took inspiration from the success of David Lynch's Blue Velvet (1986) and Peter Greenaway's The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989) and created films with bizarre alternative worlds and elements of surrealism. Japanese director Akira Kurosawa's Dreams (1990) depicted his imaginative reveries in a series of vignettes that range from idyllic pastoral country landscapes to horrific visions of tormented demons and a blighted post-nuclear war landscape. The Coen brothers' Barton Fink (1991), which won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, features various literary allusions in an enigmatic story about a writer who encounters a range of bizarre characters, including an alcoholic, abusive novelist and a serial killer. Lost Highway (1997), from the same director as Blue Velvet, is a psychological thriller that explores fantasy worlds, bizarre time-space transformations, and mental breakdowns using surreal imagery.

Other directors in the 1990s explored philosophical issues and themes such as identity, chance, death, and existentialism. Gus Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho (1991) and Wong Kar-wai's Chungking Express (1994) explored the theme of identity. The former is an independent road movie/buddy film about two young street hustlers, which explores the theme of the search for home and identity. It was called a "high-water mark in '90s independent film",[48] a "stark, poetic rumination",[49] and an "exercise in film experimentation"[50] of "high artistic quality".[26] Chungking Express[51] explores themes of identity, disconnection, loneliness, and isolation in the "metaphoric concrete jungle" of modern Hong Kong.

Daryush Shokof's film Seven Servants (1996) is an original high art cinema piece about a man who strives to "unite" the world's races until his last breath. One year after Seven Servants, Abbas Kiarostami's film Taste of Cherry (1997),[52] which won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, tells a similar tale with a different twist; both films are about a man trying to hire a person to bury him after he commits suicide. Seven Servants was shot in a minimalist style, with long takes, a leisurely pace, and long periods of silence. The film is also notable for its use of long shots and overhead shots to create a sense of distance between the audience and the characters. Zhang Yimou's early 1990s works such as Ju Dou (1990), Raise the Red Lantern (1991), The Story of Qiu Ju (1992) and To Live (1994) explore human emotions through poignant narratives. To Live won the Grand Jury Prize.

Several 1990s films explored existentialist-oriented themes related to life, chance, and death. Robert Altman's Short Cuts (1993) explores themes of chance, death, and infidelity by tracing 10 parallel and interwoven stories. The film, which won the Golden Lion and the Volpi Cup at the Venice Film Festival, was called a "many-sided, many mooded, dazzlingly structured eclectic jazz mural" by Chicago Tribune critic Michael Wilmington. Krzysztof Kieślowski's The Double Life of Véronique (1991) is a drama about the theme of identity and a political allegory about the East/West split in Europe; the film features stylized cinematography, an ethereal atmosphere, and unexplained supernatural elements.

Darren Aronofsky's film Pi (1998) is an "incredibly complex and ambiguous film filled with both incredible style and substance" about a paranoid mathematician's "search for peace".[53] The film creates a David Lynch-inspired "eerie Eraserhead-like world"[54] shot in "black-and-white, which lends a dream-like atmosphere to all of the proceedings" and explores issues such as "metaphysics and spirituality".[55] Matthew Barney's The Cremaster Cycle (1994–2002) is a cycle of five symbolic, allegorical films that creates a self-enclosed aesthetic system, aimed to explore the process of creation. The films are filled with allusions to reproductive organs and sexual development, and use narrative models drawn from biography, mythology, and geology.

In 1997, Terrence Malick returned from a 20-year absence with The Thin Red Line, a war film that uses poetry and nature to stand apart from typical war movies. It was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director.[56]

Some 1990s films mix an ethereal or surreal visual atmosphere with the exploration of philosophical issues. Satantango (1994), by the Hungarian director Bela Tarr, is a 7 1⁄2-hour-long film, shot in black and white, that deals with Tarr's favorite theme, inadequacy, as con man Irimias comes back to a village at an unspecified location in Hungary, presenting himself as a leader and Messiah figure to the gullible villagers. Kieslowski's Three Colors trilogy (1993–94), particularly Blue (1993) and Red (1994), deal with human relationships and how people cope with them in their day-to-day lives. The trilogy of films was called "explorations of spirituality and existentialism"[57] that created a "truly transcendent experience".[58] The Guardian listed Breaking the Waves (1996) as one of its top 25 arthouse films. The reviewer stated that "[a]ll the ingredients that have come to define Lars von Trier's career (and in turn, much of modern European cinema) are present here: high-wire acting, innovative visual techniques, a suffering heroine, issue-grappling drama, and a galvanising shot of controversy to make the whole thing unmissable".[59]

2000s

Lewis Beale of Film Journal International stated that Australian director Andrew Dominik's western film The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007) is "a fascinating, literary-based work that succeeds as both art and genre film".[60] Unlike the action-oriented Jesse James films of the past, Dominik's unconventional epic perhaps more accurately details the outlaw's relinquishing psyche during the final months of his life as he succumbs to the paranoia of being captured and develops a precarious friendship with his eventual assassin, Robert Ford. In 2009, director Paul Thomas Anderson claimed that his 2002 film Punch-Drunk Love about a shy, repressed rage-aholic was "an art house Adam Sandler film", a reference to the unlikely inclusion of "frat boy" comic Sandler in the film; critic Roger Ebert claims that Punch Drunk Love "may be the key to all of the Adam Sandler films, and may liberate Sandler for a new direction in his work. He can't go on making those moronic comedies forever, can he? Who would have guessed he had such uncharted depths?"[61]

2010s

Apichatpong Weerasethakul's Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, which won the 2010 Cannes Palme d'Or, "ties together what might just be a series of beautifully shot scenes with moving and funny musings on the nature of death and reincarnation, love, loss, and karma".[62] Weerasethakul is an independent film director, screenwriter, and film producer, who works outside the strict confines of the Thai film studio system. His films deal with dreams, nature, sexuality, including his own homosexuality,[63] and Western perceptions of Thailand and Asia. Weerasethakul's films display a preference for unconventional narrative structures (such as placing titles/credits at the middle of a film) and for working with non-actors.

Terrence Malick's The Tree of Life (2011) was released after decades of development and won the Palme d'Or at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival; it was highly praised by critics. At the Avon Theater in Stamford, Connecticut, a message was posted about the theater's no-refund policy due to "some customer feedback and a polarized audience response" to the film. The theater stated that it "stands behind this ambitious work of art and other challenging films".[64] Drive (2011), directed by Nicolas Winding Refn, is commonly called an arthouse action film.[65] Also in 2011, director Lars von Trier released Melancholia, a movie dealing with depression and other mental disorders while also showing a family's reaction to an approaching planet that could collide with the Earth. The movie was well received, some claiming it to be Von Trier's masterpiece with others highlighting Kirsten Dunst's performance, the visuals, and realism depicted in the movie.

Jonathan Glazer's Under the Skin was screened at the 2013 Venice Film Festival and received a theatrical release through indie studio A24 the following year. The film, starring Scarlett Johansson, follows an alien in human form as she travels around Glasgow, picking up unwary men for sex, harvesting their flesh and stripping them of their humanity. Dealing with themes such as sexuality, humanity, and objectification, the film received positive reviews[66] and was hailed by some as a masterpiece;[67] critic Richard Roeper described the film as "what we talk about when we talk about film as art".[68]

The critically acclaimed coming of age film Call Me By Your Name directed by Luca Guadagnino starring Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer was released in 2017. It was considered by many to be an art house style film, and an immediate classic of queer cinema.

This decade also saw a re-emergence of "art horror" with the success of films like Black Swan (2010), Stoker (2013), Enemy (2013), The Babadook (2014), Only Lovers Left Alive (2014), A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014), Goodnight Mommy (2014), It Follows (2015), The Witch (2015), The Wailing (2016), Split (2016), the social thriller Get Out (2017), Mother! (2017), Annihilation (2018), A Quiet Place (2018), Hereditary (2018), Suspiria (2018), Mandy (2018), The Nightingale (2018), The House That Jack Built (2018), Us (2019), Midsommar (2019), The Lighthouse (2019), Color Out of Space (2019) and the Academy Award for Best Picture winner Parasite (2019).[69][70][71][72]

Roma (2018), is a film by Alfonso Cuarón inspired by his childhood living in 1970's Mexico. Shot in black-and-white, it deals with themes shared with Cuarón's past films, such as mortality and class. The film was distributed through Netflix, earning the streaming giant their first Academy Award nomination for Best Picture.[73]

Criticism

Criticisms of art films include being too pretentious and self-indulgent for mainstream audiences.[74][75]

Related concepts

Artistic television

Quality artistic television,[76] a television genre or style which shares some of the same traits as art films, has been identified. Television shows, such as David Lynch's Twin Peaks and the BBC's The Singing Detective, also have "a loosening of causality, a greater emphasis on psychological or anecdotal realism, violations of classical clarity of space and time, explicit authorial comment, and ambiguity".[77]

As with much of Lynch's other work (notably the film Blue Velvet), Twin Peaks explores the gulf between the veneer of small-town respectability and the seedier layers of life lurking beneath its surface. The show is difficult to place in a defined television genre; stylistically, it borrows the unsettling tone and supernatural premises of horror films and simultaneously offers a bizarrely comical parody of American soap operas with a campy, melodramatic presentation of the morally dubious activities of its quirky characters. The show represents an earnest moral inquiry distinguished by both weird humor and a deep vein of surrealism, incorporating highly stylized vignettes, surrealist and often inaccessible artistic images alongside the otherwise comprehensible narrative of events.

Charlie Brooker's UK-focused Black Mirror television series explores the dark and sometimes satirical themes in modern society, particularly with regard to the unanticipated consequences of new technologies; while classified as "speculative fiction", rather than art television, it received rave reviews. HBO's The Wire might also qualify as "artistic television", as it has garnered a greater amount of critical attention from academics than most television shows receive. For example, the film theory journal Film Quarterly has featured the show on its cover.[78]

Examples of arthouse animated films

- Bombay Rose (2019)[79]

- Loving Vincent (2017)[80]

- My Life as a Zucchini (2016)[80]

- The Red Turtle (2016)[81]

- Seoul Station (2016)[81]

- In This Corner of the World (2016)[81]

- Song of the Sea (2014)[80]

- Tales from Earthsea (2007)[82]

- A Scanner Darkly (2006)[82]

- Renaissance (2006)[82]

- Paprika (2006)[82]

- Everything Will Be OK (2006)[83]

- Waking Life (2001)[84]

- Belladonna of Sadness (1973)[85]

- Fantastic Planet (1973)[86]

Notable arthouse animators

- Don Hertzfeldt[87][88]

- Richard Linklater[84]

- Michael Dudok De Wit[81]

- Satoshi Kon[82]

- Tomm Moore[80]

- René Laloux[86]

In popular media

Art films have been part of popular culture from animated sitcoms like The Simpsons[89] and Clone High spoofing and satirizing them[90] to even the comedic film review webseries Brows Held High (hosted by Kyle Kallgren).[91][92]

See also

- Independent film

- Experimental film

- Extreme cinema

- Auteur theory

- Blockbuster mentality

- Cannes Film Festival

- Classical Hollywood cinema

- Criterion Collection

- Czechoslovak New Wave

- Documentary film

- European art cinema

- Film genre

- FilmStruck

- Golden Age of Television (2000s-present)

- Independent Film Channel

- Independent Spirit Award

- L.A. Rebellion

- List of directors associated with art film

- New Hollywood

- Parallel Cinema

- Slow cinema

- Souvenirs from Earth—art TV station

- Sundance Film Festival

- Surrealist cinema

- Swansea Bay Film Festival

- Television studies

- Toronto International Film Festival

- Turner Classic Movies

- Underground film

- Video essay

- Vulgar auteurism

References

- "Art film definition". MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2007.

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company: 2009.

- Random House Kernerman Webster's College Dictionary. Random House: 2010.

- "Art film". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Wilinsky, Barbara (2001). "Sure Seaters: The Emergence of Art House Cinema". Journal of Popular Film & Television. University of Minnesota. 32: 171.

- Barry, Keith (2007). Film Genres: From Iconography to Ideology. Wallflower Press. p. 1.

- Ebert, Roger (15 March 1996). "Chungking Express Movie Review (1996)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 22 February 2018 – via www.rogerebert.com.

- Siska, William C. (1980). Modernism in the narrative cinema: the art film as a genre. Arno Press.

- Manchel, Frank (1990). Film study: an analytical bibliography. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 118.

- Peter Bondanella (2009). A History of Italian Cinema. A&C Black. ISBN 9781441160690.

- Marinetti, F. T.; Corra, Bruno; Settimelli, Emilio; Ginna, Arnaldo; Balla, Giacomo; Chiti, Remo (15 November 1916). "The Futurist Cinema Manifesto".

- Michel, Marie (2002). The French New Wave : An Artistic School. Translated by Richard Neupert. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- "French Cinema: Making Waves". archive.org. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008.

- Canby, Vincent (22 July 1969). "Movie Review – Blue Movie (1968) Screen: Andy Warhol's 'Blue Movie'". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- Canby, Vincent (10 August 1969). "Warhol's Red Hot and 'Blue' Movie. D1. Print. (behind paywall)". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- Comenas, Gary (2005). "Blue Movie (1968)". WarholStars.org. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- Paglia, Camille (8 August 2007). "Art movies: R.I.P." Salon.com. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Brody, Richard (17 January 2013). "The State of the "Art Film"". The New Yorker. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Bordwell, David (Fall 1979). "The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice" (PDF). Film Criticism. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008 – via The Wayback Machine.

- Elsaesser, Thomas (29 July 2007). "Putting on a Show: The European Art Movie". Bergmanorama: The Magic Works of Ingmar Bergman. Archived from the original on 29 July 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Williams, Christopher (5 July 2007). "The Social Art Cinema: A Moment of History in the History of British Film and Television Culture" (PDF). Cinema: The Beginnings and the Future. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2017 – via The Wayback Machine.

- Arnold Helminski, Allison. "Memories of a Revolutionary Cinema". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on 21 July 2001. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Stam, Robert; Miller, Toby (2000). Film and Theory: An Introduction. Hoboken, New Jersey: Blackwell Publishing.

- Hark, Ina Rae (2002). Exhibition, the Film Reader. London: Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 0-415-23517-0.

- Wilinsky, Barbara (2001). Sure Seaters: The Emergence of Art House Cinema. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 92. ISBN 0-8166-3562-5.

- Allmovie.com

- Howe, Desson (18 October 1991). "My Own Private Idaho". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- "Sight & Sound | Top Ten Poll 2002 – Critics Top Ten 2002". BFI. 5 September 2006. Archived from the original on 16 December 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- Movie Review – Ashani Sanket By Vincent Canby, The New York Times, 12 October 1973.

- Overview The New York Times.

- "Festival de Cannes: Andrei Rublev". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- "The Color of Pomegranates at Paradjanov.com". Parajanov.com. 9 January 2001. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- "The Color of Pomegranates in Cahiers du Cinema Top 10". Parajanov.com. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- This was Jodorowsky's second film from the 1970s. He also made El Topo (1970), a surrealistic western film.

- "13 Greatest Art-House Horror Films – Dread Central". 19 February 2016 – via www.dreadcentral.com.

- Staff (27 August 2013). "Barbara Broadcast – BluRay DVD Review". Mondo-digital.com. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Bentley, Toni (June 2014). "The Legend of Henry Paris". Playboy. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- Bentley, Toni (June 2014). "The Legend of Henry Paris" (PDF). ToniBentley.com. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- Blumenthal, Ralph (21 January 1973). "Porno chic; 'Hard-core' grows fashionable-and very profitable". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- "Porno Chic". www.jahsonic.com.

- Corliss, Richard (29 March 2005). "That Old Feeling: When Porno Was Chic". Time. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Ebert, Roger (13 June 1973). "The Devil In Miss Jones – Film Review". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- Ebert, Roger (24 November 1976). "Alice in Wonderland:An X-Rated Musical Fantasy". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- Yanaga, Tynan (14 December 2018). "PARIS, TEXAS: European Art House Meets The Great American Road Movie In Stunning Fashion".

- Roddick, Nick. "Paris, Texas: On the Road Again". The Criterion Collection.

- "Koyaanisqatsi". Spirit of Baraka. 21 May 2007. Archived from the original on 30 January 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- La Revue du cinéma, n° 393, avril 1984.

- Filmcritic.com critic Jake Euler.

- Reviewer Nick Schager.

- Critic Matt Brunson.

- Prior to Chungking Express, he directed Days of Being Wild. Later in the 1990s, Kar-wai directed Happy Together (film) (1997).

- In 1990, Kiarostami directed Close-up.

- "Pi Movie Review, DVD Release –". Filmcritic.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2005. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- "Current Movie Reviews, Independent Movies – Film Threat". Filmthreat.com. 15 June 1998. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- Critic James Berardinelli.

- 1999|Oscars.org

- Emanuel Levy, review of Three Colors: Blue. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- Matt Brunson.

- Steve Rose. "Breaking the Waves: No 24 best arthouse film of all time". the Guardian. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Lewis Beale. "The assassination of Jesse James by the coward Robert Ford". Film Journal International. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2007.

- "Punch-Drunk Love". Chicago Sun-Times.

- Satraroj, Nick. Movie review: "Uncle Boonmee", an art film for everyone Archived 23 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine. CNN. Accessed on 2 October 2010.

- "Creating His Own Language: An Interview With Apichatpong Weerasethakul", Romers, H. Cineaste, page 34, vol. 30, no. 4, Fall 2005, New York.

- Austin Dale (24 June 2011). "INTERVIEW: Here's the Story Behind That Theater's No Refund Policy for "Tree of Life"". indieWIRE. Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- "Drive (2011)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- "Under the Skin". rottentomatoes.com. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- Collin, Robbie (13 March 2014). "Under the Skin: 'simply a masterpiece'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Roeper, Richard (13 April 2014). "'Under the Skin': Brilliant mood piece about a fascinating femme fatale". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 21 April 2015 – via Richard Roeper Blog.

- Clarke, Donald (21 January 2011). "Black Swan". Irish Times. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- Ebiri, Bilge (17 April 2014). "Under the Skin and a History of Art-Horror Film". Vulture. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- D'Alessandro, Anthony (29 October 2015). "Radius Horror Film 'Goodnight Mommy' Set To Wake Up Oscar Voters As Austria's Entry". deadline.com. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- Lee, Benjamin (22 February 2016). "Did arthouse horror hit The Witch trick mainstream US audiences?". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- Tapley, Kristopher; Tapley, Kristopher (22 January 2019). "'Roma' Becomes Netflix's First Best Picture Oscar Nominee".

- Billson, Anne (5 September 2013). "The Top 10 Most Pretentious Films" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- Dekin, Mert (1 October 2019). "10 Famous Arthouse Movies That Are Too Self-Indulgent". Taste of Cinema.

- Thornton Caldwell, John (1995). Televisuality: Style, Crisis, and Authority in American Television. Rutgers University Press. p. 67.

- Thompson, Kristin (2003). Storytelling in Film and Television. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Driscoll, D. (2 November 2009). "The Wire Being Taught at Harvard". Machines.pomona.edu. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- Lodge, Guy; Lodge, Guy (29 August 2019). "Film Review: 'Bombay Rose'".

- "Euro Animated Films Offer "Darker" Art House Alternative to Hollywood, Exec Says". The Hollywood Reporter.

- "Animated Movies To Look Forward To". www.amctheatres.com.

- "Leave the Kids at Home: The Rebirth of Arthouse Animation". IFC.

- Hall, Stan; Oregonian, Special to The (3 February 2012). "Indie & Arthouse films: Don Hertzfeldt 'Everything Will Be OK', Mike Vogel's 'Did You Kiss Anyone' and more". oregonlive.

- "Dream Is Destiny: Waking Life". Animation World Network.

- "The 10 Best Animated Films You've Probably Never Seen". ScreenRant. 1 July 2019.

- "10 Essential Arthouse Sci-Fi Films". Film School Rejects. 1 September 2018.

- Thielman, Sam (24 November 2016). "The Simpsons Thanksgiving marathon: the 25 best episodes to gorge on" – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Arthouse Movie Listings December 12–18, 2012". SF Weekly. 12 December 2012.

- "Any Given Sundance" – via www.imdb.com.

- "Film Fest: Tears of a Clone" – via www.imdb.com.

- "Real Good You Guys: Kyle Kallgren and Brows Held High". 7 November 2017.

- Kallgren, Kyle (17 September 2019). "My Own Private Idaho | Brows Held High" – via Vimeo.

.jpg)