Siege of Calcutta

The Siege of Calcutta was a battle between the Bengal Subah and the British East India Company on 20 June 1756. The Nawab of Bengal, Siraj ud-Daulah, aimed to seize Calcutta to punish the Company for the unauthorised construction of fortifications at Fort William. Siraj ud-Daulah caught the Company unprepared and won a decisive victory.

| Siege of Calcutta | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Seven Years' War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Siraj-ud-Daula Mir Jafar |

Roger Drake John Zephaniah Holwell | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 30,000 - 50,000 men? | 515 - 1000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | 500 | ||||||

Origins

A trading post had been established in the area of Calcutta at the end of the seventeenth century by the East India Company, who purchased the three small villages that would later form the base of the city, and began construction of Fort William to house a garrison. In 1717 they had been granted immunity from taxation throughout Bengal by the Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar. The city flourished, with a large volume of trade travelling down the Ganges River.[1]

The attitude of the Nawabs of Bengal, the regional governors of the territory, had been one of limited toleration towards the European traders (the French and Dutch as well as the British); they were permitted to trade, but taxed heavily.

When the elderly Alivardi Khan died in 1756, he was succeeded as Nawab of Bengal by his grandson, Siraj ud-Daulah. The policy of the government changed abruptly; instead of the practical and sober approach of Alivardi, Siraj was mistrustful and impetuous. He was particularly distrustful of the British, and aimed to seize Calcutta and the large treasure he believed would be held there. From the moment he became Nawab he began searching for a pretext to drive the British from his lands; he found two.[1]

First pretext

The first pretext centered around Kissendass, the son of a high-ranking Bengali official, Raj Ballabh, who had incurred Siraj-ud-Daula's displeasure. When he was released after a brief imprisonment, Ballabh had arranged for the British to allow Kissendass to enter Calcutta along with the son's pregnant wife and family fortune, while Ballabh joined forces with those who opposed Siraj-ud-Daula's succession. The fact that the Calcutta officials continued to harbor Kissendass after Siraj-ud-Daula had become nawab--and had spurned his demand that they surrender the young man and his fortune to him--nurtured the young ruler's conviction that the British were actively plotting with his enemies at court.

Second pretext

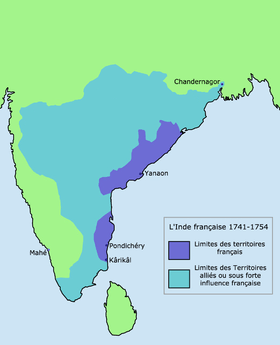

The second incident concerned the construction of new fortifications by both the British and French at their Bengali strongholds. Both nations had long been battling for dominance along the southeast coast of India, known as the Carnatic. So far, they had kept the peace in Bengal, their rivalries confined to the marketplace. But with war, though as yet undeclared, being waged between the two nations in Europe, officials at Calcutta and Chandrnagore decided that their long-neglected defenses needed to be strengthened in case hostilities erupted in Bengal. [2]

When the newly enthroned nawab learned of the new fortifications, he immediately ordered them to halt their work and to raze any new construction, promising to protect both foreign enclaves from attack as his grandfather had before him. The French, realizing just how tenuous their position in Bengal really was, meekly replied that they were not building foreign fortifications, merely repairing their existing structures.[1]

The British reacted differently. Roger Drake, the 35-year-old acting governor general of Calcutta, stated that they were only preparing for their own protection-strongly implying that the nawab would be powerless to provide it.

First Battles

Rumours quickly spread that the British gathered forces from Madras (now Chennai) and planned to invade Bengal.

By the end of May, a huge army of 50,000 strong, had been assembled under the command of Raj Durlabh. The nawab sent a letter to Governor Drake. It was no less than a declaration of war. [2]

The first disaster to befall the British came quickly. On 3 June the nawab's forces surrounded the ill-prepared East India Company fort at Cossimbazar, whose numbered only 50 men. Two days later, the garrison surrendered; the only shot fired was by the garrison commander, who committed suicide rather than submit. The nawab's army confiscated all British guns and ammunition, then marched on to Calcutta.[1]

Fort William

When the news of disaster finally reached Fort William, the fog of complacency there was replaced by panic and indecision. [3]

Acting Governor Drake combined a disastrous incapacity for planning and decision making with a degree of personal arrogance that had already alienated most of his fellow countrymen. The few men there that were capable and levelheaded were too low in the company’s hierarchy, and their advice was ignored. [2]

After the small garrison at Cossimbazar was lost, Drake and the council sent desperate pleas for help to the French and Dutch settlements. Neither wanted to join the British in their predicament.[1]

The British then implored the authorities in Madras to send reinforcements — but the issue had been decided before the letters could be answered. Drake then attempted to appease the nawab’s anger by promising to submit to all of his demands, but it was too late.[2]

Only then did the council members begin to examine the state of Fort William — and found that the fort had been neglected for so long that it was falling apart. The walls of the fort (18 feet tall, 4 feet thick) were crumbling in many places. Along the east wall large openings had been excavated during the long years of peace to admit air and light. The wooden platforms of the bastions were so rotten that they could support far fewer cannons than intended, and most of the cannons proved unusable in any case. All the south wall warehouses, or godowns, had been erected outside the fort, which precluded any flanking fire from the two south bastions.[1]

The East India Company's chief engineer, John O'Hara, advised the council to demolish the buildings surrounding the fort so the defenders could have a clear shot at an enemy attacking from any direction. The council member and chief military officer-owned houses would have to be leveled, so the council ignored O'Hara's suggestion. They decided instead to draw up a defensive line that encompassed the British Enclave that huddled about Fort William, leaving the sprawling expanse of native dwellings and marketplaces known as "Black Town"--home to well over 100,000 Indians--to the mercy of the attacking army.

Batteries were placed across the three main thoroughfares leading to the fort from the North, South, and East. The smaller streets were blocked by palisades. [3]

The plan that was drawn up would require the defensive line to be adequately manned. Yet when the garrison was mustered, everyone, including Captain-Commandant Minchin, was surprised to find only 180 men fit for duty, and only 45 were British. The rest were European half-castes, whose fighting capabilities were deemed questionable.

A militia was hastily formed from the young Company apprentices (who were known as 'writers'), the crews of many vessels that still crowded the harbor, and the European population. Manningham, and Frankland whom Drake had made Colonel and Lieutenant Colonel were appointed to command the militia. The militia added another 300 men to the defense of Calcutta, for a total of 515 troops.[1]

Defensive preparations were hampered by the disappearance of native manpower, as their lascars fled along with most of Black Town's population as the news of Siraj ud Daula's approach spread. [2]

Omichand

Omichand was the only Hindu wealthy enough to own a house in the European "White Town". Omichand recently had lost the prestigious position of chief investing and purchasing agent for the East India Company in its transaction with the Bengalis. [3]

Suspicion grew that, to gain revenge for this considerable slight, Omichand had secretly urged Siraj ud Daula to attack the British and that suspicion was confirmed when two letters from the nawab's camp (Siraj ud Daula's camp) were found addressed to Omichand. [1]

Kissendass, who was a house guest at the time of Omichand's plight, was also arrested when found with Omichand. They were then incarcerated in a small jail near Fort William's southeast bastion, in a room that was used to house drunken and disorderly sailors. The cell was ill-lit by two small, barred slits for windows that provided little light. Foul smelling and ovenlike, the small room earned the appropriate nickname, "The Black Hole."[1]

Siraj ud Daula's Advance

On 13 June the advance guard of the nawab's army was within 15 miles of Calcutta, a day's march away. All English women and children were ordered to take refuge in the fort, and the outer batteries and palisades were rushed to completion. [3] He then surrounded Fort William, and then assaulted the south wall. The gunners had no time to bring their guns up, and the Indians swarmed in. They then attacked the rest of the fort, and in little time, the fort was captured.

Aftermath

The captured prisoners were held in a prison called the Black Hole. A narrative by one John Zephaniah Holwell, plus the testimony of another survivor to a select committee of the House of Commons, placed 146 British prisoners into a room measuring 18 by 15 feet, with only 23 surviving the night. The story was amplified in colonial literature, becoming a notorious incident, but the facts are now widely disputed.[4]

The city - renamed "Alinagar" - was only lightly garrisoned by the Indians, and was recaptured in January 1757 by a force led by Robert Clive; the Nawab led a counter-attack, but this was itself attacked outside the city on 2 February and defeated. The result was a recognition of the status quo in the Treaty of Alinagar, signed on the 9th, which permitted the East India Company to remain in possession of the city and to fortify it, as well as granting them an exemption from duties.

However, the situation was fragile. Siraj was forced to send much of his army westwards to protect his territory from Ahmad Shah Durrani, leaving him militarily weak; this, coupled with personal unpopularity at home and extensive political machinations at court, gave the East India Company an opportunity to try to replace him with a new Nawab. Meanwhile, Siraj's growing involvement with the French East India Company would provide the pretext to go to war.

The result was the Battle of Plassey, on 23 June 1757, which was a decisive defeat for Siraj - betrayed by Mir Jafar, a military commander who had agreed to change sides. The battle firmly established East India Company control over Bengal, with Mir Jafar the new Nawab; it is generally seen as the start of Company rule in India, and the first major step in the development of the British Empire in India.

See also

- Great Britain in the Seven Years War

Notes

- Bedford (1997)

- Manas (2001)

- Berriedale (2003)

- Dalley, JanThe Black Hole: Money, Myth and Empire,London, Fig Tree, June 2006, ISBN 0-670-91447-9

References

- Berriedale, Keith. "The French report on Sirajuddaulah's siege of Calcutta, 1756". Project South Asia. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- Bedford, Michael; Bruce Dettman (April 1997). "The Siege of Calcutta and the Infamous Black Hole". Military History. Leesburg, Virginia (April 1997): 34–40.

- "Black Hole of Calcutta". Manas. Retrieved 4 May 2008.