Marwari people

The Marwari or Marwadi are an Indian ethnic group that originate from the Rajasthan region of India. Their language, also called Marwari, comes under the umbrella of Rajasthani languages, which is part of the Western Zone of Indo-Aryan languages.

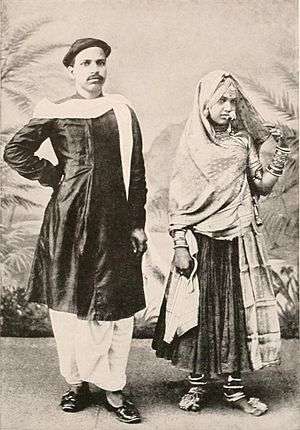

Marwari husband and wife in traditional attire | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| India | Spread across parts of India and mainly in Rajasthan |

| Nepal | 51,443[1] Terai region and Kathmandu Valley[2] |

| Languages | |

| Marwari, Hindi | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Hinduism, Jainism Minority: Islam, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Rajasthani people | |

They have been a highly successful business community, first as inland traders during the era of Rajput kingdoms, and later also as investors in industrial production and other sectors. Today, they control many of the country's largest media groups. Although spread throughout India, historically they have been most concentrated in Kolkata, Mumbai, Chennai, Delhi, Nagpur and the hinterlands of central and eastern India.

Etymology

The term Marwari once referred to the area encompassed by the former princely state of Marwar, also called the Jodhpur region of southwest Rajasthan in India. It has evolved to be a designation for the Rajasthani people in general but it is used particularly with reference to certain jātis that fall within the Bania community. The most prominent among these communities, are the Agrawals, Khandelwals, Maheshwaris and Oswals.[3] That said, most people now considered to be of the Marwari community actually have their origins in Jhunjhunu, Churu and Sikar districts of Shekhawati region of Rajasthan rather than Jodhpur; it is possible that the association of the Marwari term with Jodhpur owes more to the high status of that place in pre-independence India.[4]

Dwijendra Tripathi believes that the term Marwari was probably used by the traders only when they were outside their home region; that is, by the diaspora.[5] Anne Hardgrove also supports this argument, saying that the Marwari identity could only exist in the context of a diaspora who came from somewhere and that until they migrated they had no such designation.[4]

History

Early origins

Marwari traders have historically been migratory in habit. The possible causes of this trait include the proximity of their homeland to the major Ganges - Yamuna trade route; movement to escape famine; and the encouragement given to them by various rulers of northern India who saw advantages in having their skills in banking and finance.[3]

The pattern of Marwari migration became increasingly divergent following the decline in wars between Rajput kingdoms, which the Marwaris had helped to finance, and the decreasing influence of the community over the North Indian caravan trading routes that resulted from the British establishing themselves in the region. The changed focus of migration was also encouraged by the British establishment of new trading routes and centres, as well as by the declining political significance of the Rajput courts whose famed conspicuous consumption had been supported by Marwari money. The community welcomed the relative safety that the British presence offered, as well as the commercial and legal frameworks that they provided and which were more favourable to Marwari activities than the systems prevalent during the earlier period of Mughal and Rajput rule.[6]

The Marwari Jagat Seth family served as bankers to the Mughals.

British era

After the decline of Mughal authority in Bengal, Marwari traders, bankers and financiers migrated to the growing British power in Calcutta.[7] There were particularly significant population shifts to Bombay between 1835-1850 and Kolkata from the 1870s, as well as to Madras.[6] They continued to spread into areas of British control throughout the nineteenth century, becoming established as sahukars (moneylenders) and inland trade-brokers in central India and Maharashtra. The migration of these traders accelerated in the second half of the nineteenth century which led to growing unpopularity, and acts of communal violence against them.

Historian Medha M. Kudaisya has said that the Marwaris:

made the transition from being niche players in trading to becoming industrial conglomerates ... From being brokers and bankers, the Marwaris went on to break the British monopoly over the jute industry after World War I; they then moved into other industrial sectors, such as cotton and sugar, and set up diversified conglomerates. By the 1950s, the Marwaris dominated the India private industry scenario, emerging as the establishers of its most prominent business houses.[8]

A considerable number of Marwari business groups made their fortune on speculative markets in the nineteenth and early twentieth century.[9]

Although maintaining close and public ties with the British authorities, members of the Marwari business community were early financial supporters of the Indian National Congress, often in secret.[9]

Independent India

In 1956, the All-India Marwari Federation opposed a linguistic organisation of states whilst buying up regional language newspapers in Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh.[10] Today, they control many of the country's largest media groups.[11]

The community's control of the Indian economy declined following the country's 1991 economic reforms. From a peak of controlling 24 per cent in 1990, it had fallen to less than 2 per cent in 2000. This reflects the growth of new industries outside of commodities trading and primary production. The figure for year "2000" is considered to be lower than the position in 1939, when the community first began its resurgence.[12]

Language

Marwari, or Marrubhasha, as it is referred to by Marwaris, is the traditional, historical, language of the Marwari ethnicity. The Marwari language is closely related to the Rajasthani language. The latter evolved from the Old Gujarati (also called Old Western Rajasthani, Gujjar Bhakha or Maru-Gurjar), language spoken by the people in Gujarat and Rajasthan.[13] It has been noted that throughout the state of Rajasthan, people avoid identifying their language by name, preferring to identify themselves as speaking "Rajasthani" with Marwari literature and taught as Rajasthani until secondary level.[14]

Culture

Marwaris have been known for a tightly-knit social solidarity, described by Selig Harrison in 1960 as "indissoluble under the impact of the strongest regional solvents".[15] The perception held of their culture by other communities is ambivalent at best. Hardgrove notes that they are "known across India for their success in business and industry , and often despised and severely criticised by other Indians for their alleged corruption and social conservatism". The latter aspect is particularly evident in the status of women within the Marwari community: it is probably correct that, generally speaking, they are less educated than those of even other wealthy communities and if they have any form of further education it tends not to be with the aim of pursuing a career but rather of enhancing domestic life. According to Hardgrove, "The main duty for Marwari women, it would seem, is to provide a stable household life for their husbands, sons and brothers-in-law", although she acknowledges that some such women have in recent years been attempting to carve out roles in the wider world through engagement in charitable ventures and even running their own businesses.[4]

Notable people

- Binod Chaudhary[16]

- Nidhhi Agerwal[17]

- Janaki Devi Bajaj[18]

- Rahul Bajaj[18]

- Shobhana Bhartia[19]

- Kumar Mangalam Birla[20]

- Aditya Chaudhary - Nepalese footballer

- Jagmohan Dalmiya[21]

- Ritu Dalmia[22]

- S. N. Goenka[23]

- Abhishek Jain[24]

- Shyamanand Jalan[25]

- Rajeev Khandelwal[26]

- Rohit Khandelwal[27]

- Abhishek Singhvi[18]

- Shantanu Maheshwari

- Laxmi Mall Singhvi[28][18]

- Liaquat Soldier Pakistani comedy actor, writer and director

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marwari people. |

- "Nepal Census 2011" (PDF).

- "Marwari peoples starts fleeing Nepal". The Times of India. 17 April 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Kudaisya, Medha M. (2009). "Marwari and Chettiar Merchants. 1850s-1950s: Comparative Trajectories". In Kudaisya, Medha M.; Ng, Chin-Keong (eds.). Chinese and Indian Business: Historical Antecedents. Leiden: BRILL. p. 87. ISBN 978-90-04-17279-1. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Hardgrove, Anne (August 1999). "Sati Worship and Marwari Public Identity in India". The Journal of Asian Studies. 58 (3): 723–752. doi:10.2307/2659117. JSTOR 2659117.

- Tripathi, Dwijendra (1996). "From Community to Class: The Marwaris in a Historical Perspective". In Bhandani, B. L.; Tripathi, Dwijendra (eds.). Facets of a Marwar Historian. Jaipur: Publication Scheme. pp. 189–196. ISBN 978-81-86782-18-7.

- Kudaisya, Medha M. (2009). "Marwari and Chettiar Merchants. 1850s-1950s: Comparative Trajectories". In Kudaisya, Medha M.; Ng, Chin-Keong (eds.). Chinese and Indian Business: Historical Antecedents. Leiden: BRILL. p. 88. ISBN 978-90-04-17279-1. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Strasser, Susan (2013). Commodifying Everything : Relationships of the Market. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-13670-685-1.

- Kudaisya, Medha M. (2009). "Marwari and Chettiar Merchants. 1850s-1950s: Comparative Trajectories". In Kudaisya, Medha M.; Ng, Chin-Keong (eds.). Chinese and Indian Business: Historical Antecedents. Leiden: BRILL. p. 86. ISBN 978-90-04-17279-1. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Timberg, Thomas A. (2014). The Marwaris: from Jagat Seth to the Birlas. New Delhi: Portfolio Penguin. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-14342-405-5.

- The Times of India, 11 February 1956, p. 3.

- Ajwani, Deepak (18 March 2014). "Indian Media: Marwaris Write the Script | Forbes India". Forbes India. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Niyogi, Subhro (6 May 2002). "Marwaris losing business acumen". The Times of India. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Ajay Mitra Shastri; R. K. Sharma; Devendra Handa (2005). Revealing India's past: recent trends in art and archaeology. Aryan Books International. p. 227. ISBN 978-81-7305-287-3.

It is an established fact that during 10th-11th century ... Interestingly the language was known as the Gujjar Bhakha.

- Mukherjee, Kakali (2011). "Marwari" (PDF). Census India. p. 35.

- Harrison, Selig, S. (1960). India: the most dangerous decades. Princeton University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-40087-780-5.

- "Binod Chaudhary – My Story: From the Streets of Kathmandu to a Billion Dollar Empire" (PDF). 28 May 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Nidhhi Agerwal: I am a Tollywood buff who grew up watching Telugu films dubbed in Hindi - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Taknet, D. K. (2016). The Marwari Heritage. IntegralDMS. p. 254. ISBN 9781942322061. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Jain, Gunjan (2018). Shobhana Bhartia: (Penguin Petit). Penguin Random House India Private Limited. ISBN 9789353054175. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "The story of the first couple of the Birla empire". Rediff. 6 June 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Choudhury, Angikaar (21 September 2015). "Jagmohan Dalmiya (1940-2015): The man who symbolised India's clout in world cricket". Scroll.in. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Dalmia, Ritu (12 August 2016). "My freedom to love: 'I was 23 when I realised I was gay. I told my parents. The next day they sent a box of mangoes for my partner at the time'". India Today. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "You have to work out your own salvation - Indian Express". archive.indianexpress.com. 3 July 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "'કેવી રીતે જઈશ' અને 'બે યાર'ના સર્જક અભિષેક જૈન કહે છે...એ ઘટનાએ જ મારી ગુજરાતી ફિલ્મ બનાવવાની ધગશને વધુ પ્રગટાવી" (in Gujarati). 2 May 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "Shyamanand Jalan: Eminenet theatre actor Shyamanand Jalan dead | Kolkata News - Times of India". The Times of India. 25 May 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "rediff.com: Rajeev Khandelwal chats with Rediff Readers". www.rediff.com. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- TT Bureau (18 September 2016). "Man of the world". The Telegraph. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Singhvi, Abhishek Manu; Malik, Lokendra (2018). India's Vibgyor Man: Selected Writings and Speeches of L.M. Singhvi. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-909407-3. Retrieved 31 December 2019.