Leh

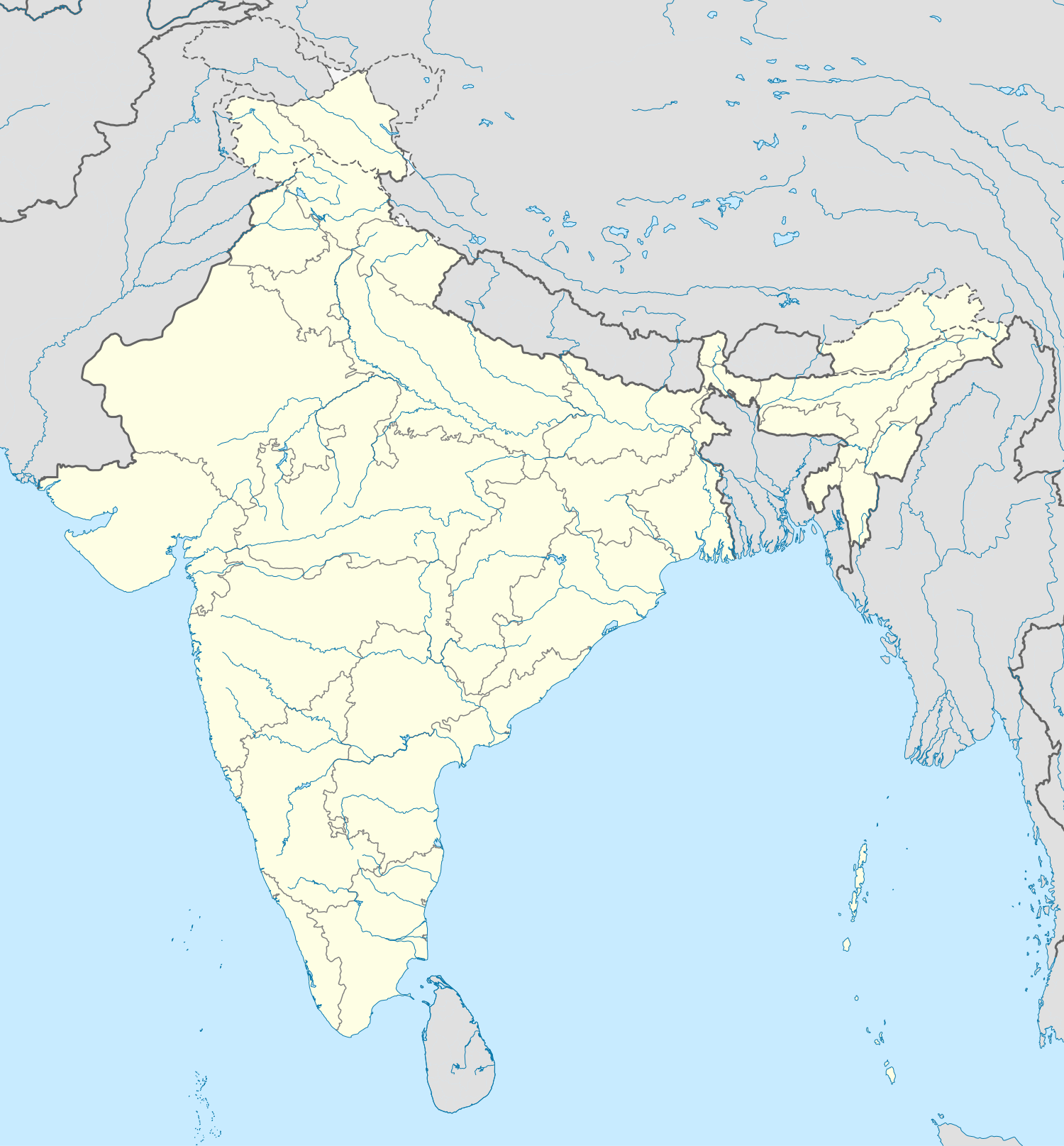

Leh (Hindi: लेह; Ladakhi/Tibetan script: གླེ་ or སླེ་, Wylie: Gle or sle ) is the joint capital and largest town of the union territory of Ladakh in India. Leh, located in the Leh district, was also the historical capital of the Himalayan Kingdom of Ladakh, the seat of which was in the Leh Palace, the former residence of the royal family of Ladakh, built in the same style and about the same time as the Potala Palace in Tibet. Leh is at an altitude of 3,524 metres (11,562 ft), and is connected via National Highway 1 to Srinagar in the southwest and to Manali in the south via the Leh-Manali Highway.

Leh | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

Leh  Leh | |

| Coordinates: 34.16°N 77.58°E | |

| Country | |

| Union territory | Ladakh |

| District | Leh |

| Government | |

| • Type | Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, Leh |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.15 km2 (3.53 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 3,500 m (11,500 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 30,870 |

| • Density | 3,400/km2 (8,700/sq mi) |

| Demographics | |

| • Languages | Ladakhi, Balti, Hindi, English[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| Vehicle registration | LA 01 |

| Website | leh |

History

.jpeg)

Leh was an important stopover on trade routes along the Indus Valley between Tibet to the east, Kashmir to the west and also between India and China for centuries. The main goods carried were salt, grain, pashm or cashmere wool, charas or cannabis resin from the Tarim Basin, indigo, silk yarn and Banaras brocade.

Although there are a few indications that the Chinese knew of a trade route through Ladakh to India as early as the Kushan period (1st to 3rd centuries CE),[2] and certainly by Tang dynasty,[3] little is actually known of the history of the region before the formation of the kingdom towards the end of the 10th century by the Tibetan prince, Skyid lde nyima gon (or Nyima gon), a grandson of the anti-Buddhist Tibetan king, Langdarma (r. c. 838 to 841). He conquered Western Tibet although his army originally numbered only 300 men. Several towns and castles are said to have been founded by Nyima gon and he apparently ordered the construction of the main sculptures at Shey. "In an inscription, he says he had them made for the religious benefit of the Tsanpo (the dynastical name of his father and ancestors), and of all the people of Ngaris (Western Tibet). This shows that already in this generation Langdarma's opposition to Buddhism had disappeared."[4] Shey, just 15 km east of modern Leh, was the ancient seat of the Ladakhi kings.

During the reign of Delegs Namgyal (1660–1685),[5] the Nawab of Kashmir, which was then a province in the Mughal Empire, arranged for the Mongol army to temporarily leave Ladakh, though it returned later. As payment for assisting Delegs Namgyal in the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal war of 1679–1684, the Nawab made a number of onerous demands. One of the least was to build a large Sunni Muslim mosque in Leh at the upper end of the bazaar in Leh, below the Leh Palace. The mosque reflects a mixture of Islamic and Tibetan architecture and can accommodate more than 500 people. This was apparently not the first mosque in Leh; there are two smaller ones which are said to be older.[6]

Several trade routes have traditionally converged on Leh, from all four directions. The most direct route was the one the modern highway follows from the Punjab via Mandi, the Kulu valley, over the Rohtang Pass, through Lahaul and on to the Indus Valley, and then downriver to Leh. The route from Srinagar was roughly the same as the road that today crosses the Zoji La (pass) to Kargil, and then up the Indus Valley to Leh. From Baltistan there were two difficult routes: the main on ran up the Shyok Valley from the Indus, over a pass and then down the Hanu River to the Indus again below Khalsi (Khalatse). The other ran from Skardu straight up the Indus to Kargil and on to Leh. Then, there were both the summer and winter routes from Leh to Yarkand via the Karakoram Pass and Xaidulla. Finally, there were a couple of possible routes from Leh to Lhasa.[7]

The first recorded royal residence in Ladakh, built at the top of the high Namgyal ('Victory') Peak overlooking the present palace and town, is the now-ruined fort and the gon-khang (Temple of the Guardian Divinities) built by King Tashi Namgyal. Tashi Namgyal is known to have ruled during the final quarter of the 16th century CE.[8] The Namgyal (also called "Tsemo Gompa" = 'Red Gompa', or dGon-pa-so-ma = 'New Monastery'),[9] a temple, is the main Buddhist centre in Leh.[10] There are some older walls of fortifications behind it which Francke reported used to be known as the "Dard Castle." If it was indeed built by Dards, it must pre-date the establishment of Tibetan rulers in Ladakh over a thousand years ago.[11]

Below this are the Chamba (Byams-pa, i.e., Maitreya) and Chenresi (sPyan-ras-gzigs, i.e. Avalokiteshvara) monasteries which are of uncertain date.[9]

The royal palace, known as Leh Palace, was built by King Sengge Namgyal (1612–1642), presumably between the period when the Portuguese Jesuit priest, Francisco de Azevedo, visited Leh in 1631, and made no mention of it, and Sengge Namgyal's death in 1642.[12]

The Leh Palace is nine storeys high; the upper floors accommodated the royal family, and the stables and storerooms are located on the lower floors. The palace was abandoned when Kashmiri forces besieged it in the mid-19th century. The royal family moved their premises south to their current home in Stok Palace on the southern bank of the Indus.

- "As has already been mentioned, the original name of the town is not sLel, as it is nowadays spelled, but sLes, which signifies an encampment of nomads. These [Tibetan] nomads were probably in the habit of visiting the Leh valley at a time when it had begun to be irrigated by Dard colonisers. Thus, the most ancient part of the ruins on the top of rNam-rgyal-rtse-mo hill at Leh are called 'aBrog-pal-mkhar (Dard castle). . . . "[13]

In 2010, Leh was heavily damaged by the sudden floods caused by a cloud burst.

Administration

Unlike other districts in India, the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC) is in charge of governance in Leh. It has 30 councillors, 4 nominated and 26 elected. The Chief Executive Councillor heads and chairs this council. . The 'Deputy Commissioner, Leh' also holds the power of 'Chief Executive Officer of the LAHDC'. The Current Deputy Commissioner of Leh district is Sachin Kumar Vaishya.

The Old Town of Leh

The old town of Leh was added to the World Monuments Fund's list of 100 most endangered sites due to increased rainfall from climate change and other reasons.[14] Neglect and changing settlement patterns within the old town have threatened the long-term preservation of this unique site.[15]

The rapid and poorly planned urbanisation of Leh has increased the risk of flash floods in some areas, while other areas, according to research by the Climate and Development Knowledge Network, suffer from the less dramatic, gradual effects of ‘invisible disasters’, which often go unreported.[16]

Geography

Mountains dominate the landscape around the Leh as it is at an altitude of 3,500m. The principal access roads include the 434 km Srinagar-Leh highway which connects Leh with Srinagar and the 473 km Leh-Manali Highway which connects Manali with Leh. Both roads are open only on a seasonal basis.[17] Although the access roads from Srinagar and Manali are often blocked by snow in winter, the local roads in the Indus Valley usually remain open due to the low level of precipitation and snowfall.

Climate

Leh has a cold desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWk) with long, cold winters from late November to early March, with minimum temperatures well below freezing for most of the winter. The city gets occasional snowfall during winter. The weather in the remaining months is generally fine and warm during the day. Average annual rainfall is only 102 mm (4.02 inches). In 2010 the city experienced flash floods which killed more than 100 people.[18]

Climate data for Leh (1951–1980) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 8.3 (46.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

23.9 (75.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

34.8 (94.6) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

34.8 (94.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

1.5 (34.7) |

6.5 (43.7) |

12.3 (54.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.3 (77.5) |

21.7 (71.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

2.3 (36.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −14.4 (6.1) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

3.2 (37.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.5 (50.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

5.8 (42.4) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−11.8 (10.8) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28.3 (−18.9) |

−26.4 (−15.5) |

−19.4 (−2.9) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

0.6 (33.1) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−17.5 (0.5) |

−25.6 (−14.1) |

−28.3 (−18.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 9.5 (0.37) |

8.1 (0.32) |

11.0 (0.43) |

9.1 (0.36) |

9.0 (0.35) |

3.5 (0.14) |

15.2 (0.60) |

15.4 (0.61) |

9.0 (0.35) |

7.5 (0.30) |

3.6 (0.14) |

4.6 (0.18) |

105.5 (4.15) |

| Average rainy days | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 13.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 51 | 51 | 46 | 36 | 30 | 26 | 33 | 34 | 31 | 27 | 40 | 46 | 38 |

| Source: India Meteorological Department[19][20] | |||||||||||||

Agriculture

.jpg)

Leh is located at an average elevation of about 3500 metres, which means that only one crop a year can be grown there, while two can be grown at Khalatse. By the time crops are being sown at Leh in late May, they are already half-grown at Khalatse. The main crop is grim (naked barley - Hordeum vulgare L. var. nudum Hook. f., which is an ancient form of domesticated barley with an easier to remove hull) - from which tsampa, the staple food in Ladakh, is made.[21] The water for agriculture of Ladakh comes from the Indus, which runs low in March and April when barley-fields have the greatest need for irrigation.[22]

Demographics

As of 2001 India census,[23] Leh town had a population of 27,513. Males constitute 61% of the population and females 39%, due to a large presence of non-local labourers, traders and government employees. Leh has an average literacy rate of 75%, close to the national average of 74.04%: male literacy is 82.14%, and female literacy is 65.46%. In Leh, 9% of the population is under 6 years of age. The people of Leh are ethnic Tibetan, speaking Ladakhi, a Tibetic language.

The Muslim presence dates back to the annexation of Ladakh by Kashmir, after the Fifth Dalai Lama attempted to invade Ladakh from Tibet. Since then, there has been further migration from the Kashmir Valley due firstly to trade and latterly with the transfer of tourism from the Kashmir Valley to Ladakh.

Ladakh receives very large numbers of tourists for its size. In 2010, 77,800 tourists arrived in Leh. Numbers of visitors have swelled rapidly in recent years, increasing 77% in the 5 years to 2010. This growth is largely accounted for by larger numbers of trips by domestic Indian travellers.[24]

Religion

Coexistence with religions other than Buddhism

Hinduism is the oldest religion in the valley, having the second largest number of followers after Buddhism. Since the 8th-century people belonging to different religions, particularly Buddhism and Islam, have been living in Leh. They co-inhabited the region from the time of early period of Namgyal dynasty and there are no records of any conflict between them.

"This mosque was built by Ibraheem Khan (in the mid 17th century),[26] who was a man of noble family in the service of the descendants of Timoor. In his time the Kalimaks (Calmuck Tartars), having invaded and obtained possession of the greater portion of Thibet [Ladakh], the Raja of that country claimed protection from the Emperor of Hindoostan. Ibraheem Khan was accordingly deputed by that monarch to his assistance, and in a short time succeeded in expelling the invaders and placing the Raja once more on his throne. The Raja embraced the Mahomedan faith, and formally acknowledged himself as a feudatory of the Emperor, who honored him with the title of Raja Akibut Muhmood Khan, which title to the present day is borne by the Ruler of Cashmere."[27]

In recent times, relations between the Buddhist and Muslim communities soured due to political conflicts.

Besides these two communities there are people living in the region who belong to other religions such as Christianity, Hinduism and Sikhism. The small Christian community in Leh are descendants of converts from Tibetan Buddhism by German Moravian missionaries who established a church at Keylong in Lahaul in the 1860s, and were allowed to open another mission in Leh in 1885 and had a sub-branch in Khalatse. They stayed open until Indian Independence in 1947. In spite of their successful medical and educational activities, they made only a few converts.[28]

Every year Sindhu Darshan Festival is held at Shey, 15 km away from town to promote religious harmony and glory of Indus (Sindhu) river. At this time, many tourists visit Leh.[29]

Attractions

In Leh

- Leh Palace

- Namgyal Tsemo Gompa

- Shanti Stupa

- Cho Khang Gompa

- Chamba Temple

- Jama Masjid

- Gurdwara Pathar Sahib

- Sankar Gompa and village

- War Museum

- The Victory Tower

- Zorawar Fort

- Ladakh Marathon

- Datun Sahib

From Leh as day trips or longer

- Khardung La

- Spituk Monastery

- Stok Palace & Stok Monastery

- Thikse Monastery

- Shey Monastery

- Hemis Monastery

- Basgo

- Alchi Monastery

- Magnetic Hill (India)

- Indus River - Zanskar River sangam (confluence)

- Pangong Tso

- Tsomoriri Wetland Conservation Reserve (Tsomoriri Lake)

- Hunder Valley

- Sand Dunes Nubra

- Siachen Glacier

- Ti-suru

- Turtuk

- Trekking Trails e.g. Markha Valley

Transport

Leh is connected to the rest of India by two high-altitude roads both of which are subject to landslides and neither of which are passable in winter when covered by deep snows. The National Highway 1D from Srinagar via Kargil is generally open longer. The Leh-Manali Highway can be troublesome due to very high passes and plateaus, and the lower but landslide-prone Rohtang Pass near Manali.

The overland approach to Ladakh from the Kashmir valley via the 434-km. National Highway 1 typically remains open for traffic from June to October/November. The most dramatic part of this road journey is the ascent up the 3,505 m (11,500 ft.) high Zoji-la, a tortuous pass in the Great Himalayan Wall. The Jammu and Kashmir State Road Transport Corporation (JKSRTC) operates regular Deluxe and Ordinary bus services between Srinagar and Leh on this route with an overnight halt at Kargil. Taxis (cars and jeeps) are also available at Srinagar for the journey.

- National Highway 3 or Leh-Manali Highway

Since 1989, the 473-km Leh-Manali Highway has been serving as the second land approach to Ladakh. Open for traffic from June to late October, this high road traverses the upland desert plateaux of Rupsho whose altitude ranges from 3,660 m to 4,570 m. There are a number of high passes en route among which the highest one, known as Tanglang La, is sometimes (but incorrectly) claimed to be the world's second highest motorable pass at an altitude of 5,325 m. (17,469 feet). See the article on Khardung La for a discussion of the world's highest motorable passes.

- Air

Leh's Leh Kushok Bakula Rimpochee Airport has flights to Delhi at least daily on Air India which also provides twice weekly services to Jammu and a weekly flight to Srinagar. Connect in Delhi for other destinations. Go Air operates Delhi to Leh daily flights during peak time.

- Rail

There is no railway service currently in Ladakh, however 2 railway routes are proposed- the Bilaspur–Leh line and Srinagar–Kargil–Leh line for more information.[30]

Media and communications

State-owned All India Radio has a local station in Leh, which transmits various programs of mass interest.

Images

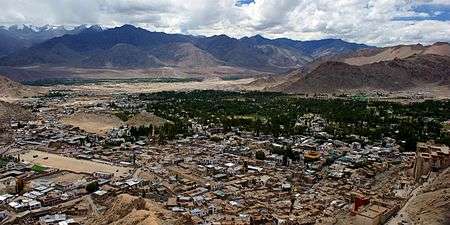

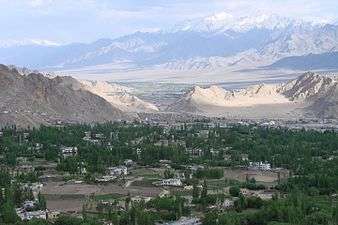

View of Leh

View of Leh View of Leh from Khardung La Road

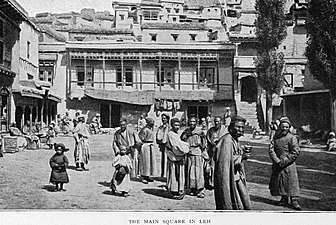

View of Leh from Khardung La Road Leh, capital of Ladakh ca. 1857

Leh, capital of Ladakh ca. 1857 The city-square in 1909

The city-square in 1909 Shanti Stupa, constructed in 1983 by the Japanese

Shanti Stupa, constructed in 1983 by the Japanese Namgyal Tsemo Gompa in Leh

Namgyal Tsemo Gompa in Leh Leh Mosque

Leh Mosque Leh in winter

Leh in winter Complete view of Leh as seen from Shanti Stupa

Complete view of Leh as seen from Shanti Stupa.jpg) Alternate view

Alternate view- Leh in summer

Leh viewed from Stok

Leh viewed from Stok Landscapes near Leh

Landscapes near Leh Shanti Stupa, Leh

Shanti Stupa, Leh Gurudwara Pathar Sahib Leh ,Ladakh

Gurudwara Pathar Sahib Leh ,Ladakh Gurudwara Pathar Sahib, Leh , Ladakh

Gurudwara Pathar Sahib, Leh , Ladakh Gurudwara Pathar Sahib, Leh, Ladakh

Gurudwara Pathar Sahib, Leh, Ladakhhill.jpg) Magnetic Hill, Leh, Ladakh

Magnetic Hill, Leh, Ladakh

See also

Footnotes

- Zutshi, Chitralekha (2004). Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir. Hurst & Company. ISBN 9781850656944.

- Hill (2009), pp. 200-204.

- Francke (1977 edition), pp. 76-78

- Francke (1914), pp. 89-90.

- Francke (1977 edition), p. 20.

- Francke (1977 edition), pp. 120-123.

- Rizvi (1996), pp. 109-111.

- Rizvi (1996), p. 64.

- Francke (1914), p. 70.

- Rizvi (1996), pp. 41, 64, 225-226.

- Rizvi (1996), pp. 226-227.

- Rizvi (1996), pp. 69, 290.

- Francke (1914), p. 68. See also, ibid, p. 45.

- "Tourist Boom Brings Threat to Leh's Tibetan Architecture". AFP. 19 August 2007.

- Tripti Lahiri (23 August 2007). "Ethnic Leh Houses Falling Apart". AFP. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008.

- Local approaches to harmonising climate adaptation and disaster risk reduction: Lessons from India, Anshu Sharma, Sahba Chauhan and Sunny Kumar, the Climate and Development Knowledge Network, 2014 cdkn.org

- The Journey from Kashmir

- Polgreen, Lydia (6 August 2010). "Mudslides Kill 125 in Kashmir". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- "Leh Climatological Table Period: 1951–1980". India Meteorological Department. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- "Leh Climatological Table Period: 1951–1980". India Meteorological Department. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Rizvi (1996), p. 38.

- "Jammu & Kashmir - Geography & Geology". Peace kashmir. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- "Census of India 2001: Data from the 2001 Census, including cities, villages and towns (Provisional)". Census Commission of India. Archived from the original on 16 June 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "District Census Handbook, Leh" (PDF). Census of India 2011. Directorate of Census Operations. p. 60. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- A History of Ladakh. A. H. Francke with critical introduction and annotations by S. S. Gergan & F. M. Hassnain. Sterling Publishers, New Delhi. 1977, pp. 52, 123

- Travels in Central Asia by Meer Izzut-oollah in the Years 1812-13. Translated by Captain Henderson. Calcutta, 1872, p. 12.

- Rizvi (1996), p. 212.

- Sindhu Darshan Festival

- "How to Reach Leh". The Indian Backpacker. December 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

References

- Janet Rizvi. Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia. Second Edition. (1996). Oxford University Press, Delhi. ISBN 0-19-564546-4.

- Cunningham, Alexander. (1854). LADĀK: Physical, Statistical, and Historical with Notices of the Surrounding Countries. London. Reprint: Sagar Publications (1977).

- Francke, A. H. (1977). A History of Ladakh. (Originally published as, A History of Western Tibet, (1907)). 1977 Edition with critical introduction and annotations by S. S. Gergan & F. M. Hassnain. Sterling Publishers, New Delhi.

- Francke, A. H. (1914). Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Two Volumes. Calcutta. 1972 reprint: S. Chand, New Delhi.

- Hilary Keating (July–August 1993). "The Road to Leh". Saudi Aramco World. Houston, Texas: Aramco Services Company. 44 (4): 8–17. ISSN 1530-5821. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

Further reading

- Lonely Planet: Trekking in the Himalayas (Walking Guides)

- Indiator: Hill stations in India