Carboniferous

The Carboniferous (/ˌkɑːr.bəˈnɪf.ər.əs/ KAHR-bə-NIF-ər-əs)[2] is a geologic period and system that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period 358.9 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, 298.9 Mya. The name Carboniferous means "coal-bearing" and derives from the Latin words carbō ("coal") and ferō ("I bear, I carry"), and was coined by geologists William Conybeare and William Phillips in 1822.[3]

| Carboniferous Period 358.9–298.9 million years ago | |

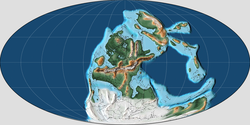

A map of the world as it appeared during the Late Carboniferous. (300 ma) | |

| Mean atmospheric O 2 content over period duration |

c. 32.3 vol % (162 % of modern level) |

| Mean atmospheric CO 2 content over period duration |

c. 800 ppm (3 times pre-industrial level) |

| Mean surface temperature over period duration | c. 14 °C (0 °C above modern level) |

| Sea level (above present day) | Falling from 120 m to present-day level throughout the Mississippian, then rising steadily to about 80 m at end of period[1] |

Based on a study of the British rock succession, it was the first of the modern 'system' names to be employed, and reflects the fact that many coal beds were formed globally during that time.[4] The Carboniferous is often treated in North America as two geological periods, the earlier Mississippian and the later Pennsylvanian.[5] Terrestrial animal life was well established by the Carboniferous period.[6] Amphibians were the dominant land vertebrates, of which one branch would eventually evolve into amniotes, the first solely terrestrial vertebrates.

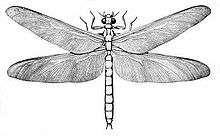

Arthropods were also very common, and many (such as Meganeura) were much larger than those of today. Vast swaths of forest covered the land, which would eventually be laid down and become the coal beds characteristic of the Carboniferous stratigraphy evident today. Also during this period, the atmospheric content of oxygen reached its highest levels in geological history, 35%[7] compared with 21% today, allowing terrestrial invertebrates to evolve to great size.[7]

The later half of the period experienced glaciations, low sea level, and mountain building as the continents collided to form Pangaea. A minor marine and terrestrial extinction event, the Carboniferous rainforest collapse, occurred at the end of the period, caused by climate change.[8]

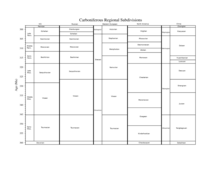

Subdivisions

In the United States the Carboniferous is usually broken into Mississippian (earlier) and Pennsylvanian (later) subperiods. The Mississippian is about twice as long as the Pennsylvanian, but due to the large thickness of coal-bearing deposits with Pennsylvanian ages in Europe and North America, the two subperiods were long thought to have been more or less equal in duration.[9]

In Europe the Lower Carboniferous sub-system is known as the Dinantian, comprising the Tournaisian and Visean Series, dated at 362.5-332.9 Ma, and the Upper Carboniferous sub-system is known as the Silesian, comprising the Namurian, Westphalian, and Stephanian Series, dated at 332.9-298.9 Ma. The Silesian is roughly contemporaneous with the late Mississippian Serpukhovian plus the Pennsylvanian. In Britain the Dinantian is traditionally known as the Carboniferous Limestone, the Namurian as the Millstone Grit, and the Westphalian as the Coal Measures and Pennant Sandstone.

The International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) faunal stages (in bold) from youngest to oldest, together with some of their regional subdivisions, are:

| System | Series (NW Europe) |

Stage (NW Europe) |

Series (ICS) |

Stage (ICS) |

Age (Ma) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permian | younger | ||||

| Carboniferous | Silesian | Stephanian | Pennsylvanian | Gzhelian | 298.9–303.7 |

| Westphalian | Kasimovian | 303.7–307.0 | |||

| Moscovian | 307.0–315.2 | ||||

| Bashkirian | 315.2–323.2 | ||||

| Namurian | |||||

| Mississippian | Serpukhovian | 323.2–330.9 | |||

| Dinantian | Visean | Visean | 330.9–346.7 | ||

| Tournaisian | Tournaisian | 346.7–358.9 | |||

| Devonian | older | ||||

| Subdivisions of the Carboniferous system in Europe compared with the official ICS-stages (as of 2018) | |||||

Late Pennsylvanian: Gzhelian (most recent)

- Noginskian / Virgilian (part)

Late Pennsylvanian: Kasimovian

- Klazminskian

- Dorogomilovskian / Virgilian (part)

- Chamovnicheskian / Cantabrian / Missourian

- Krevyakinskian / Cantabrian / Missourian

Middle Pennsylvanian: Moscovian

- Myachkovskian / Bolsovian / Desmoinesian

- Podolskian / Desmoinesian

- Kashirskian / Atokan

- Vereiskian / Bolsovian / Atokan

Early Pennsylvanian: Bashkirian / Morrowan

- Melekesskian / Duckmantian

- Cheremshanskian / Langsettian

- Yeadonian

- Marsdenian

- Kinderscoutian

Late Mississippian: Serpukhovian

- Alportian

- Chokierian / Chesterian / Elvirian

- Arnsbergian / Elvirian

- Pendleian

Middle Mississippian: Visean

- Brigantian / St Genevieve / Gasperian / Chesterian

- Asbian / Meramecian

- Holkerian / Salem

- Arundian / Warsaw / Meramecian

- Chadian / Keokuk / Osagean (part) / Osage (part)

Early Mississippian: Tournaisian (oldest)

- Ivorian / (part) / Osage (part)

- Hastarian / Kinderhookian / Chouteau

Palaeogeography

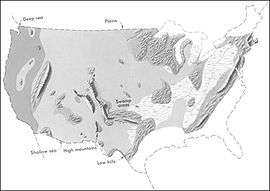

A global drop in sea level at the end of the Devonian reversed early in the Carboniferous; this created the widespread inland seas and the carbonate deposition of the Mississippian.[10] There was also a drop in south polar temperatures; southern Gondwanaland was glaciated throughout the period, though it is uncertain if the ice sheets were a holdover from the Devonian or not.[10] These conditions apparently had little effect in the deep tropics, where lush swamps, later to become coal, flourished to within 30 degrees of the northernmost glaciers.[10]

Mid-Carboniferous, a drop in sea level precipitated a major marine extinction, one that hit crinoids and ammonites especially hard.[10] This sea level drop and the associated unconformity in North America separate the Mississippian subperiod from the Pennsylvanian subperiod. This happened about 323 million years ago, at the onset of the Permo-Carboniferous Glaciation.[10]

The Carboniferous was a time of active mountain-building as the supercontinent Pangaea came together. The southern continents remained tied together in the supercontinent Gondwana, which collided with North America–Europe (Laurussia) along the present line of eastern North America. This continental collision resulted in the Hercynian orogeny in Europe, and the Alleghenian orogeny in North America; it also extended the newly uplifted Appalachians southwestward as the Ouachita Mountains.[10] In the same time frame, much of present eastern Eurasian plate welded itself to Europe along the line of the Ural Mountains. Most of the Mesozoic supercontinent of Pangea was now assembled, although North China (which would collide in the Latest Carboniferous), and South China continents were still separated from Laurasia. The Late Carboniferous Pangaea was shaped like an "O."

There were two major oceans in the Carboniferous—Panthalassa and Paleo-Tethys, which was inside the "O" in the Carboniferous Pangaea. Other minor oceans were shrinking and eventually closed - Rheic Ocean (closed by the assembly of South and North America), the small, shallow Ural Ocean (which was closed by the collision of Baltica and Siberia continents, creating the Ural Mountains) and Proto-Tethys Ocean (closed by North China collision with Siberia/Kazakhstania).

Climate

Average global temperatures in the Early Carboniferous Period were high: approximately 20 °C (68 °F). However, cooling during the Middle Carboniferous reduced average global temperatures to about 12 °C (54 °F). Lack of growth rings of fossilized trees suggest a lack of seasons of a tropical climate. Glaciations in Gondwana, triggered by Gondwana's southward movement, continued into the Permian and because of the lack of clear markers and breaks, the deposits of this glacial period are often referred to as Permo-Carboniferous in age.

The cooling and drying of the climate led to the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse (CRC) during the late Carboniferous. Tropical rainforests fragmented and then were eventually devastated by climate change.[8]

Rocks and coal

Carboniferous rocks in Europe and eastern North America largely consist of a repeated sequence of limestone, sandstone, shale and coal beds.[11] In North America, the early Carboniferous is largely marine limestone, which accounts for the division of the Carboniferous into two periods in North American schemes. The Carboniferous coal beds provided much of the fuel for power generation during the Industrial Revolution and are still of great economic importance.

The large coal deposits of the Carboniferous may owe their existence primarily to two factors. The first of these is the appearance of wood tissue and bark-bearing trees. The evolution of the wood fiber lignin and the bark-sealing, waxy substance suberin variously opposed decay organisms so effectively that dead materials accumulated long enough to fossilise on a large scale. The second factor was the lower sea levels that occurred during the Carboniferous as compared to the preceding Devonian period. This promoted the development of extensive lowland swamps and forests in North America and Europe. Based on a genetic analysis of mushroom fungi, it was proposed that large quantities of wood were buried during this period because animals and decomposing bacteria and fungi had not yet evolved enzymes that could effectively digest the resistant phenolic lignin polymers and waxy suberin polymers. They suggest that fungi that could break those substances down effectively only became dominant towards the end of the period, making subsequent coal formation much rarer.[12]

The Carboniferous trees made extensive use of lignin. They had bark to wood ratios of 8 to 1, and even as high as 20 to 1. This compares to modern values less than 1 to 4. This bark, which must have been used as support as well as protection, probably had 38% to 58% lignin. Lignin is insoluble, too large to pass through cell walls, too heterogeneous for specific enzymes, and toxic, so that few organisms other than Basidiomycetes fungi can degrade it. To oxidize it requires an atmosphere of greater than 5% oxygen, or compounds such as peroxides. It can linger in soil for thousands of years and its toxic breakdown products inhibit decay of other substances.[13] One possible reason for its high percentages in plants at that time was to provide protection from insects in a world containing very effective insect herbivores (but nothing remotely as effective as modern plant eating insects) and probably many fewer protective toxins produced naturally by plants than exist today. As a result, undegraded carbon built up, resulting in the extensive burial of biologically fixed carbon, leading to an increase in oxygen levels in the atmosphere; estimates place the peak oxygen content as high as 35%, as compared to 21% today.[14] This oxygen level may have increased wildfire activity. It also may have promoted gigantism of insects and amphibians — creatures that have been constrained in size by respiratory systems that are limited in their physiological ability to transport and distribute oxygen at the lower atmospheric concentrations that have since been available.[15]

In eastern North America, marine beds are more common in the older part of the period than the later part and are almost entirely absent by the late Carboniferous. More diverse geology existed elsewhere, of course. Marine life is especially rich in crinoids and other echinoderms. Brachiopods were abundant. Trilobites became quite uncommon. On land, large and diverse plant populations existed. Land vertebrates included large amphibians.

Life

Plants

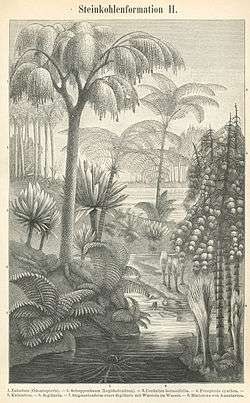

Early Carboniferous land plants, some of which were preserved in coal balls, were very similar to those of the preceding Late Devonian, but new groups also appeared at this time.

The main Early Carboniferous plants were the Equisetales (horse-tails), Sphenophyllales (scrambling plants), Lycopodiales (club mosses), Lepidodendrales (scale trees), Filicales (ferns), Medullosales (informally included in the "seed ferns", an artificial assemblage of a number of early gymnosperm groups) and the Cordaitales. These continued to dominate throughout the period, but during late Carboniferous, several other groups, Cycadophyta (cycads), the Callistophytales (another group of "seed ferns"), and the Voltziales (related to and sometimes included under the conifers), appeared.

The Carboniferous lycophytes of the order Lepidodendrales, which are cousins (but not ancestors) of the tiny club-moss of today, were huge trees with trunks 30 meters high and up to 1.5 meters in diameter. These included Lepidodendron (with its cone called Lepidostrobus), Anabathra, Lepidophloios and Sigillaria. The roots of several of these forms are known as Stigmaria. Unlike present-day trees, their secondary growth took place in the cortex, which also provided stability, instead of the xylem.[16] The Cladoxylopsids were large trees, that were ancestors of ferns, first arising in the Carboniferous.[17]

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Coal Plants. |

The fronds of some Carboniferous ferns are almost identical with those of living species. Probably many species were epiphytic. Fossil ferns and "seed ferns" include Pecopteris, Cyclopteris, Neuropteris, Alethopteris, and Sphenopteris; Megaphyton and Caulopteris were tree ferns.

The Equisetales included the common giant form Calamites, with a trunk diameter of 30 to 60 cm (24 in) and a height of up to 20 m (66 ft). Sphenophyllum was a slender climbing plant with whorls of leaves, which was probably related both to the calamites and the lycopods.

Cordaites, a tall plant (6 to over 30 meters) with strap-like leaves, was related to the cycads and conifers; the catkin-like reproductive organs, which bore ovules/seeds, is called Cardiocarpus. These plants were thought to live in swamps. True coniferous trees (Walchia, of the order Voltziales) appear later in the Carboniferous, and preferred higher drier ground.

Marine invertebrates

In the oceans the marine invertebrate groups are the Foraminifera, corals, Bryozoa, Ostracoda, brachiopods, ammonoids, hederelloids, microconchids and echinoderms (especially crinoids). For the first time foraminifera take a prominent part in the marine faunas. The large spindle-shaped genus Fusulina and its relatives were abundant in what is now Russia, China, Japan, North America; other important genera include Valvulina, Endothyra, Archaediscus, and Saccammina (the latter common in Britain and Belgium). Some Carboniferous genera are still extant.

The microscopic shells of radiolarians are found in cherts of this age in the Culm of Devon and Cornwall, and in Russia, Germany and elsewhere. Sponges are known from spicules and anchor ropes, and include various forms such as the Calcispongea Cotyliscus and Girtycoelia, the demosponge Chaetetes, and the genus of unusual colonial glass sponges Titusvillia.

Both reef-building and solitary corals diversify and flourish; these include both rugose (for example, Caninia, Corwenia, Neozaphrentis), heterocorals, and tabulate (for example, Chladochonus, Michelinia) forms. Conularids were well represented by Conularia

Bryozoa are abundant in some regions; the fenestellids including Fenestella, Polypora, and Archimedes, so named because it is in the shape of an Archimedean screw. Brachiopods are also abundant; they include productids, some of which (for example, Gigantoproductus) reached very large (for brachiopods) size and had very thick shells, while others like Chonetes were more conservative in form. Athyridids, spiriferids, rhynchonellids, and terebratulids are also very common. Inarticulate forms include Discina and Crania. Some species and genera had a very wide distribution with only minor variations.

Annelids such as Serpulites are common fossils in some horizons. Among the mollusca, the bivalves continue to increase in numbers and importance. Typical genera include Aviculopecten, Posidonomya, Nucula, Carbonicola, Edmondia, and Modiola. Gastropods are also numerous, including the genera Murchisonia, Euomphalus, Naticopsis. Nautiloid cephalopods are represented by tightly coiled nautilids, with straight-shelled and curved-shelled forms becoming increasingly rare. Goniatite ammonoids are common.

Trilobites are rarer than in previous periods, on a steady trend towards extinction, represented only by the proetid group. Ostracoda, a class of crustaceans, were abundant as representatives of the meiobenthos; genera included Amphissites, Bairdia, Beyrichiopsis, Cavellina, Coryellina, Cribroconcha, Hollinella, Kirkbya, Knoxiella, and Libumella.

Amongst the echinoderms, the crinoids were the most numerous. Dense submarine thickets of long-stemmed crinoids appear to have flourished in shallow seas, and their remains were consolidated into thick beds of rock. Prominent genera include Cyathocrinus, Woodocrinus, and Actinocrinus. Echinoids such as Archaeocidaris and Palaeechinus were also present. The blastoids, which included the Pentreinitidae and Codasteridae and superficially resembled crinoids in the possession of long stalks attached to the seabed, attain their maximum development at this time.

- Aviculopecten subcardiformis; a bivalve from the Logan Formation (Lower Carboniferous) of Wooster, Ohio (external mold).

Bivalves (Aviculopecten) and brachiopods (Syringothyris) in the Logan Formation (Lower Carboniferous) in Wooster, Ohio.

Bivalves (Aviculopecten) and brachiopods (Syringothyris) in the Logan Formation (Lower Carboniferous) in Wooster, Ohio.- Syringothyris sp.; a spiriferid brachiopod from the Logan Formation (Lower Carboniferous) of Wooster, Ohio (internal mold).

- Palaeophycus ichnosp.; a trace fossil from the Logan Formation (Lower Carboniferous) of Wooster, Ohio.

- Crinoid calyx from the Lower Carboniferous of Ohio with a conical platyceratid gastropod (Palaeocapulus acutirostre) attached.

Conulariid from the Lower Carboniferous of Indiana.

Conulariid from the Lower Carboniferous of Indiana. Tabulate coral (a syringoporid); Boone Limestone (Lower Carboniferous) near Hiwasse, Arkansas.

Tabulate coral (a syringoporid); Boone Limestone (Lower Carboniferous) near Hiwasse, Arkansas.

Freshwater and lagoonal invertebrates

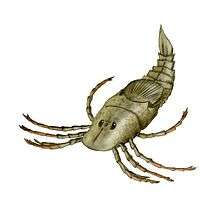

Freshwater Carboniferous invertebrates include various bivalve molluscs that lived in brackish or fresh water, such as Anthraconaia, Naiadites, and Carbonicola; diverse crustaceans such as Candona, Carbonita, Darwinula, Estheria, Acanthocaris, Dithyrocaris, and Anthrapalaemon.

The eurypterids were also diverse, and are represented by such genera as Adelophthalmus, Megarachne (originally misinterpreted as a giant spider, hence its name) and the specialised very large Hibbertopterus. Many of these were amphibious.

Frequently a temporary return of marine conditions resulted in marine or brackish water genera such as Lingula, Orbiculoidea, and Productus being found in the thin beds known as marine bands.

Terrestrial invertebrates

Fossil remains of air-breathing insects,[18] myriapods and arachnids[19] are known from the late Carboniferous, but so far not from the early Carboniferous.[6] The first true priapulids appeared during this period. Their diversity when they do appear, however, shows that these arthropods were both well developed and numerous. Their large size can be attributed to the moistness of the environment (mostly swampy fern forests) and the fact that the oxygen concentration in the Earth's atmosphere in the Carboniferous was much higher than today.[20] This required less effort for respiration and allowed arthropods to grow larger with the up to 2.6-meter-long (8.5 ft) millipede-like Arthropleura being the largest-known land invertebrate of all time. Among the insect groups are the huge predatory Protodonata (griffinflies), among which was Meganeura, a giant dragonfly-like insect and with a wingspan of ca. 75 cm (30 in)—the largest flying insect ever to roam the planet. Further groups are the Syntonopterodea (relatives of present-day mayflies), the abundant and often large sap-sucking Palaeodictyopteroidea, the diverse herbivorous Protorthoptera, and numerous basal Dictyoptera (ancestors of cockroaches).[18] Many insects have been obtained from the coalfields of Saarbrücken and Commentry, and from the hollow trunks of fossil trees in Nova Scotia. Some British coalfields have yielded good specimens: Archaeoptitus, from the Derbyshire coalfield, had a spread of wing extending to more than 35 cm (14 in); some specimens (Brodia) still exhibit traces of brilliant wing colors. In the Nova Scotian tree trunks land snails (Archaeozonites, Dendropupa) have been found.

Fish

Many fish inhabited the Carboniferous seas; predominantly Elasmobranchs (sharks and their relatives). These included some, like Psammodus, with crushing pavement-like teeth adapted for grinding the shells of brachiopods, crustaceans, and other marine organisms. Other sharks had piercing teeth, such as the Symmoriida; some, the petalodonts, had peculiar cycloid cutting teeth. Most of the sharks were marine, but the Xenacanthida invaded fresh waters of the coal swamps. Among the bony fish, the Palaeonisciformes found in coastal waters also appear to have migrated to rivers. Sarcopterygian fish were also prominent, and one group, the Rhizodonts, reached very large size.

Most species of Carboniferous marine fish have been described largely from teeth, fin spines and dermal ossicles, with smaller freshwater fish preserved whole.

Freshwater fish were abundant, and include the genera Ctenodus, Uronemus, Acanthodes, Cheirodus, and Gyracanthus.

Sharks (especially the Stethacanthids) underwent a major evolutionary radiation during the Carboniferous.[21] It is believed that this evolutionary radiation occurred because the decline of the placoderms at the end of the Devonian period caused many environmental niches to become unoccupied and allowed new organisms to evolve and fill these niches.[21] As a result of the evolutionary radiation Carboniferous sharks assumed a wide variety of bizarre shapes including Stethacanthus which possessed a flat brush-like dorsal fin with a patch of denticles on its top.[21] Stethacanthus's unusual fin may have been used in mating rituals.[21]

Akmonistion of the shark order Symmoriida roamed the oceans of the early Carboniferous.

Akmonistion of the shark order Symmoriida roamed the oceans of the early Carboniferous. Falcatus was a Carboniferous shark, with a high degree of sexual dimorphism.

Falcatus was a Carboniferous shark, with a high degree of sexual dimorphism.

Tetrapods

Carboniferous amphibians were diverse and common by the middle of the period, more so than they are today; some were as long as 6 meters, and those fully terrestrial as adults had scaly skin.[22] They included a number of basal tetrapod groups classified in early books under the Labyrinthodontia. These had long bodies, a head covered with bony plates and generally weak or undeveloped limbs. The largest were over 2 meters long. They were accompanied by an assemblage of smaller amphibians included under the Lepospondyli, often only about 15 cm (6 in) long. Some Carboniferous amphibians were aquatic and lived in rivers (Loxomma, Eogyrinus, Proterogyrinus); others may have been semi-aquatic (Ophiderpeton, Amphibamus, Hyloplesion) or terrestrial (Dendrerpeton, Tuditanus, Anthracosaurus).

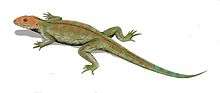

The Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse slowed the evolution of amphibians who could not survive as well in the cooler, drier conditions. Reptiles, however, prospered due to specific key adaptations.[8] One of the greatest evolutionary innovations of the Carboniferous was the amniote egg, which allowed the laying of eggs in a dry environment, allowing for the further exploitation of the land by certain tetrapods. These included the earliest sauropsid reptiles (Hylonomus), and the earliest known synapsid (Archaeothyris). These small lizard-like animals quickly gave rise to many descendants, including reptiles, birds, and mammals.

Reptiles underwent a major evolutionary radiation in response to the drier climate that preceded the rainforest collapse.[8][23] By the end of the Carboniferous period, amniotes had already diversified into a number of groups, including protorothyridids, captorhinids, araeoscelids, and several families of pelycosaurs.

Petrolacosaurus, the first diapsid reptile known, lived during the late Carboniferous.

Petrolacosaurus, the first diapsid reptile known, lived during the late Carboniferous. Archaeothyris was a very early synapsid and the oldest known.

Archaeothyris was a very early synapsid and the oldest known.

Fungi

As plants and animals were growing in size and abundance in this time (for example, Lepidodendron), land fungi diversified further. Marine fungi still occupied the oceans. All modern classes of fungi were present in the Late Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian Epoch).[24]

During the Carboniferous, animals and bacteria had great difficulty with processing the lignin and cellulose that made up the gigantic trees of the period. Microbes had not evolved that could process them. The trees, after they died, simply piled up on the ground, occasionally becoming part of long-running wildfires after a lightning strike, with others very slowly degrading into coal. White rot fungus were the first living creatures to be able to process these and break them down in any reasonable quantity and timescale. Thus, fungi helped end the Carboniferous period, stopping the endless pile-up of dead trees in Earth's forests of the era and breaking trees open to release their carbon back into the atmosphere.[25][26]

Extinction events

Romer's gap

The first 15 million years of the Carboniferous had very limited terrestrial fossils. This gap in the fossil record is called Romer's gap after the American palaentologist Alfred Romer. While it has long been debated whether the gap is a result of fossilisation or relates to an actual event, recent work indicates the gap period saw a drop in atmospheric oxygen levels, indicating some sort of ecological collapse.[27] The gap saw the demise of the Devonian fish-like ichthyostegalian labyrinthodonts, and the rise of the more advanced temnospondyl and reptiliomorphan amphibians that so typify the Carboniferous terrestrial vertebrate fauna.

Carboniferous rainforest collapse

Before the end of the Carboniferous Period, an extinction event occurred. On land this event is referred to as the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse (CRC).[8] Vast tropical rainforests collapsed suddenly as the climate changed from hot and humid to cool and arid. This was likely caused by intense glaciation and a drop in sea levels.[28]

The new climatic conditions were not favorable to the growth of rainforest and the animals within them. Rainforests shrank into isolated islands, surrounded by seasonally dry habitats. Towering lycopsid forests with a heterogeneous mixture of vegetation were replaced by much less diverse tree-fern dominated flora.

Amphibians, the dominant vertebrates at the time, fared poorly through this event with large losses in biodiversity; reptiles continued to diversify due to key adaptations that let them survive in the drier habitat, specifically the hard-shelled egg and scales, both of which retain water better than their amphibian counterparts.[8]

See also

- Carboniferous tetrapods

- Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse

- Important Carboniferous Lagerstätten

- East Kirkton Quarry; c. 350 mya; Bathgate, Scotland

- Hamilton Quarry; 320 mya; Kansas, US

- Mazon Creek; 300 mya; Illinois, US

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

References

- Haq, B. U.; Schutter, SR (2008). "A Chronology of Paleozoic Sea-Level Changes". Science. 322 (5898): 64–68. Bibcode:2008Sci...322...64H. doi:10.1126/science.1161648. PMID 18832639. S2CID 206514545.

- Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Conybeare & Phillips 1822, p. 323: "Book III. Medial or Carboniferous Order.".

- Cossey et al. 2004, p. 3.

- "The Carboniferous Period". www.ucmp.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-02-10.

- Garwood & Edgecombe 2011.

- Beerling 2007, p. 47.

- Sahney, S.; Benton, M.J. & Falcon-Lang, H.J. (2010). "Rainforest collapse triggered Pennsylvanian tetrapod diversification in Euramerica". Geology. 38 (12): 1079–1082. Bibcode:2010Geo....38.1079S. doi:10.1130/G31182.1.

- Menning et al. 2006.

- Stanley 1999.

- Stanley 1999, p. 426.

- Floudas, D.; Binder, M.; Riley, R.; Barry, K.; Blanchette, R. A.; Henrissat, B.; Martinez, A. T.; et al. (28 June 2012). "The Paleozoic Origin of Enzymatic Lignin Decomposition Reconstructed from 31 Fungal Genomes". Science. 336 (6089): 1715–1719. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1715F. doi:10.1126/science.1221748. hdl:10261/60626. PMID 22745431. S2CID 37121590.

Biello, David (28 June 2012). "White Rot Fungi Slowed Coal Formation". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2013. - Robinson 1990, p. 608.

- "Ancient Animals Got a Rise out of Oxygen". highbeam.com. 13 May 1995. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Dudley 1998.

- "A History of Palaeozoic Forests - Part 2 The Carboniferous coal swamp forests". Forschungsstelle für Paläobotanik. Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster. Archived from the original on 2012-09-20.

- Hogan, C. Michael (2010). "Fern". Encyclopedia of Earth. Washington, DC: National council for Science and the Environment. Archived from the original on November 9, 2011.

- Garwood & Sutton 2010.

- Garwood, Dunlop & Sutton 2009.

- Verberk, Wilco C.E.P.; Bilton, David T. (July 27, 2011). "Can Oxygen Set Thermal Limits in an Insect and Drive Gigantism?". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e22610. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622610V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022610. PMC 3144910. PMID 21818347.

- Martin, R. Aidan. "A Golden Age of Sharks". Biology of Sharks and Rays | ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Archived from the original on 2008-05-22. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- Stanley 1999, pp. 411-412.

- Kazlev, M. Alan (1998). "The Carboniferous Period of the Paleozoic Era: 299 to 359 million years ago". Palaeos.org. Archived from the original on 2008-06-21. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- Blackwell, Meredith; Vilgalys, Rytas; James, Timothy Y.; Taylor, John W. (2008). "Fungi. Eumycota: mushrooms, sac fungi, yeast, molds, rusts, smuts, etc". Archived from the original on 2008-09-24. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- Biello, D. (2012). "White Rot Fungi Slowed Coal Formation". Scientific American. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Krulwich, R. (2016). "The Fantastically Strange Origin of Most Coal on Earth". National Geographic. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Ward, P.; Labandeira, Conrad; Laurin, Michel; Berner, Robert A. (November 7, 2006). "Confirmation of Romer's Gap is a low oxygen interval constraining the timing of initial arthropod and vertebrate terrestrialization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (45): 16818–16822. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10316818W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607824103. PMC 1636538. PMID 17065318.

- Heckel, P.H. (2008). "Pennsylvanian cyclothems in Midcontinent North America as far-field effects of waxing and waning of Gondwana ice sheets". Resolving the Late Paleozoic Ice Age in Time and Space:Geological Society of America Special Paper. 441: 275–289. doi:10.1130/2008.2441(19). ISBN 978-0-8137-2441-6.

Sources

- Beerling, David (2007). The Emerald Planet: How Plants Changed Earth's History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192806024.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Conybeare, W. D.; Phillips, William (1822). Outlines of the geology of England and Wales : with an introductory compendium of the general principles of that science, and comparative views of the structure of foreign countries. Part I. London: William Phillips. OCLC 1435921.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cossey, P.J.; Adams, A.E.; Purnell, M.A.; Whiteley, M.J.; Whyte, M.A.; Wright, V.P. (2004). British Lower Carboniferous Stratigraphy. Geological Conservation Review. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee. p. 3. ISBN 1-86107-499-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dudley, Robert (24 March 1998). "Atmospheric Oxygen, Giant Paleozoic Insects and the Evolution of Aerial Locomotor Performance" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology. 201 (Pt 8): 1043–1050. PMID 9510518. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garwood, Russell J.; Edgecombe, Gregory (2011). "Early terrestrial animals, evolution and uncertainty". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 4 (3): 489–501. doi:10.1007/s12052-011-0357-y.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garwood, Russell J.; Dunlop, Jason A.; Sutton, Mark D. (2009). "High-fidelity X-ray micro-tomography reconstruction of siderite-hosted Carboniferous arachnids". Biology Letters. 5 (6): 841–844. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0464. PMC 2828000. PMID 19656861.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garwood, Russell J.; Sutton, Mark D. (2010). "X-ray micro-tomography of Carboniferous stem-Dictyoptera: New insights into early insects". Biology Letters. 6 (5): 699–702. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0199. PMC 2936155. PMID 20392720.

- Menning, M.; Alekseev, A.S.; Chuvashov, B.I.; Davydov, V.I.; Devuyst, F.X.; Forke, H.C.; Grunt, T.A.; et al. (2006). "Global time scale and regional stratigraphic reference scales of Central and West Europe, East Europe, Tethys, South China, and North America as used in the Devonian–Carboniferous–Permian Correlation Chart 2003 (DCP 2003)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 240 (1–2): 318–372. Bibcode:2006PPP...240..318M. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.03.058.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ogg, Jim (June 2004). "Overview of Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSP's)". Archived from the original on April 23, 2006. Retrieved April 30, 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stanley, S.M. (1999). Earth System History. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0-7167-2882-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, JM (1990). "Lignin, land plants, and fungi: Biological evolution affecting Phanerozoic oxygen balance". Geology. 18 (7): 607–610. Bibcode:1990Geo....18..607R. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1990)015<0607:llpafb>2.3.co;2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

![]()

External links

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Paleozoic#Carboniferous |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carboniferous. |

- "Geologic Time Scale 2004". International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- Examples of Carboniferous Fossils

- 60+ images of Carboniferous Foraminifera

- Carboniferous (Chronostratography scale)