Mapuche

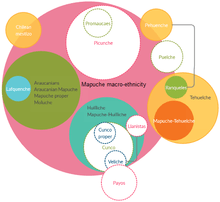

The Mapuche are a group of indigenous inhabitants of present-day south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of present-day Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who shared a common social, religious, and economic structure, as well as a common linguistic heritage as Mapudungun speakers. Their influence once extended from Aconcagua Valley to Chiloé Archipelago and spread later eastward to the Argentine pampa. Today the collective group makes up over 80% of the indigenous peoples in Chile, and about 9% of the total Chilean population. The Mapuche are particularly concentrated in the Araucanía region. Many have migrated from rural areas to the cities of Santiago and Buenos Aires for economic opportunities.

.jpg) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 1,950,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Chile | 1,745,147 (2017)[1] |

| Argentina | 205,009 (2010)[2] |

| Languages | |

| Mapudungun • Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Evangelicalism, Catholicism, traditional | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Core groups: Boroano, Cunco, Huilliche, Lafquenche, Moluche, Picunche, Promaucae Araucanized groups: Pehuenche, Puelche, Ranquel, Tehuelche | |

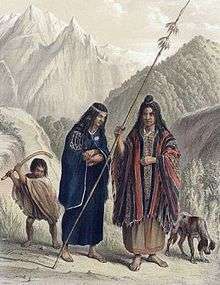

The Mapuche traditional economy is based on agriculture; their traditional social organization consists of extended families, under the direction of a lonko or chief. In times of war, the Mapuche would unite in larger groupings and elect a toki (meaning "axe, axe-bearer") to lead them. Mapuche are known for the textiles woven by women, which have been goods for trade for centuries, since before the arrival of European explorers and colonists.

At the time of Spanish arrival, the Araucanian Mapuche inhabited the valleys between the Itata and Toltén rivers. South of there, the Huilliche and the Cunco lived as far south as the Chiloé Archipelago. In the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Mapuche groups migrated eastward into the Andes and pampas, fusing and establishing relationships with the Poya and Pehuenche. At about the same time, ethnic groups of the pampa regions, the Puelche, Ranquel and northern Aonikenk, made contact with Mapuche groups. The Tehuelche adopted the Mapuche language and some of their culture, in what came to be called Araucanization.

Mapuche in the Spanish-ruled areas, specially the Picunche, mingled with Spanish during the colonial period, forming a mestizo population and losing their indigenous identity. But Mapuche society in Araucanía and Patagonia remained independent until the late nineteenth century, when Chile occupied Araucanía and Argentina conquered Puelmapu. Since then the Mapuche have become subjects, and then nationals and citizens of the respective states. Today, many Mapuche and Mapuche communities are engaged in the so-called Mapuche conflict over land and indigenous rights in both Argentina and in Chile.

Etymology

Historically the Spanish colonizers of South America referred to the Mapuche people as Araucanians (araucanos). This term is now considered pejorative[3] by some people. The name was likely derived from the placename rag ko (Spanish Arauco), meaning "clayey water".[4][5] The Quechua word awqa, meaning "rebel, enemy", is probably not the root of araucano.[4]

Scholars believe that the various Mapuche groups (Moluche, Huilliche, Picunche, etc.) called themselves Reche during the early Spanish colonial period, due to what they referred to as their pure native blood, derived from Re meaning pure and Che meaning people.[6]

The name "Mapuche" is used both to refer collectively to the Picunche, Huilliche and Moluche or Nguluche from Araucanía, or at other times, exclusively to the Moluche or Nguluche from Araucanía. However, Mapuche is a relatively recent endonym meaning "People of the Earth" or "Children of the Earth", "mapu" means earth and "che" means person. It is preferred as a term when referring to the "Mapuche" people after the Arauco War.[7]

The Mapuche identify by the geography of their territories, such as:

- Pwelche or Puelche: "people of the east" occupied Pwel mapu or Puel mapu, the eastern lands (Pampa and Patagonia of Argentina).

- Pikunche or Picunche: "people of the north" occupied Pikun-mapu, the "northern lands".

- Williche or Huilliche: "people of the south" occupied Willi mapu, the "southern lands".

- Pewenche or Pehuenche: "people of the pewen/pehuen" occupied Pewen mapu, "the land of the pewen (Araucaria araucana) tree".

- Lafkenche: "people of the sea" occupied Lafken mapu, "the land of the sea"; also known as Coastal Mapuche.

- Nagche: "people of the plains" occupied Nag mapu, "the land of the plains" (located in sectors of the Cordillera de Nahuelbuta and the low zones bordering it). The ancient Mapuche Toqui ("axe-bearer") like Lef-Traru ("swift hawk", better known as Lautaro), Kallfülikan ("blue quartz stone", better known as Caupolicán – "polished flint") or Pelontraru ("Shining Caracara", better known as Pelantaro) were Nagche.

- Wenteche: "people of the valleys" occupied Wente mapu, "the land of the valleys".[8]

History

Pre–Columbian period

Archaeological finds have shown that Mapuche culture existed in Chile and Argentina as early as 600 to 500 BC.[9] Genetically the Mapuche differ from the adjacent indigenous peoples of Patagonia.[10] This suggests a "different origin or long lasting separation of Mapuche and Patagonian populations".[10]

Troops of the Inca Empire are reported to have reached the Maule River and had a battle with the Mapuche between the Maule and the Itata Rivers there.[11] The southern border of the Inca Empire is believed by most modern scholars to have been situated between Santiago and the Maipo River, or somewhere between Santiago and the Maule River.[12] Thus the bulk of the Mapuche escaped Inca rule. Through their contact with Incan invaders Mapuches would have for the first time met people with state organization. Their contact with the Incas gave them a collective awareness distinguishing between them and the invaders and uniting them into loose geo-political units despite their lack of state organization.[13]

At the time of the arrival of the first Spaniards to Chile the largest indigenous population concentration was in the area spanning from Itata River to Chiloé Island—that is the Mapuche heartland.[14] The Mapuche population between Itata River and Reloncaví Sound has been estimated at 705,000–900,000 in the mid-sixteenth century by historian José Bengoa.[15][note 1]

Arauco War

The Spanish expansion into Mapuche territory was an offshoot of the conquest of Peru.[16] In 1541 Pedro de Valdivia reached Chile from Cuzco and founded Santiago.[17] The northern Mapuche tribes, known as Promaucaes and Picunches, fought unsuccessfully against Spanish conquest. Little is known about their resistance.[18]

In 1550 Pedro de Valdivia, who aimed to control all of Chile to the Straits of Magellan, campaigned in south-central Chile to conquer more Mapuche territory.[19] Between 1550 and 1553 the Spanish founded several cities[note 2] in Mapuche lands including Concepción, Valdivia, Imperial, Villarrica and Angol.[19] The Spanish also established the forts of Arauco, Purén and Tucapel.[19] Further efforts by the Spanish to gain more territory engaged them in the Arauco War against the Mapuche, a sporadic conflict that lasted nearly 350 years. Hostility towards the conquerors was compounded by the lack of a tradition of forced labour akin to the Inca mita among the Mapuche, who largely refused to serve the Spanish.[21]

From their establishment in 1550 to 1598, the Mapuche frequently laid siege to Spanish settlements in Araucanía.[20] The war was mostly a low intensity conflict.[22] Mapuche numbers decreased significantly following contact with the Spanish invaders; wars and epidemics decimated the population.[18] Others died in Spanish owned gold mines.[21]

In 1598 a party of warriors from Purén led by Pelantaro, who were returning south from a raid in Chillán area, ambushed Martín García Óñez de Loyola and his troops[23] while they rested without taking any precautions against attack. Almost all the Spaniards died, save a cleric named Bartolomé Pérez, who was taken prisoner, and a soldier named Bernardo de Pereda. The Mapuche then initiated a general uprising which destroyed all the cities in their homeland south of the Biobío River.

In the years following the Battle of Curalaba a general uprising developed among the Mapuches and Huilliches. The Spanish cities of Angol, Imperial, Osorno, Santa Cruz de Oñez, Valdivia and Villarrica were either destroyed or abandoned.[24] Only Chillán and Concepción resisted Mapuche sieges and raids.[25] With the exception of Chiloé Archipelago, all Chilean territory south of the BíoBío River was freed from Spanish rule.[24] In this period the Mapuche Nation crossed the Andes to conquer the present Argentine provinces of Chubut, Neuquen, La Pampa and Río Negro.

Incorporation into Chile and Argentina

In the nineteenth century Chile experienced a fast territorial expansion. Chile established a colony at the Strait of Magellan in 1843, settled Valdivia, Osorno and Llanquihue with German immigrants and conquered land from Peru and Bolivia.[26][27] Later Chile would also annex Easter Island.[28] In this context Araucanía began to be conquered by Chile due to two reasons. First, the Chilean state aimed for territorial continuity[29] and second it remained the sole place for Chilean agriculture to expand.[30]

Between 1861 and 1871 Chile incorporated several Mapuche territories in Araucanía. In January 1881, having decisively defeated Peru in the battles of Chorrillos and Miraflores, Chile resumed the conquest of Araucanía.[31][32][33]

Historian Ward Churchill has claimed that the Mapuche population dropped from a total of half a million to 25,000 within a generation as result of the occupation and its associated famine and disease.[34] The conquest of Araucanía caused numerous Mapuches to be displaced and forced to roam in search of shelter and food.[35] Scholar Pablo Miramán claims the introduction of state education during the Occupation of Araucanía had detrimental effects on traditional Mapuche education.[36]

In the years following the occupation the economy of Araucanía changed from being based on sheep and cattle herding to one based on agriculture and wood extraction.[37] The loss of land by Mapuches following the occupation caused severe erosion since Mapuches continued to practice a massive livestock herding in limited areas.[38]

Modern conflict

Land disputes and violent confrontations continue in some Mapuche areas, particularly in the northern sections of the Araucanía region between and around Traiguén and Lumaco. In an effort to defuse tensions, the Commission for Historical Truth and New Treatments issued a report in 2003 calling for drastic changes in Chile's treatment of its indigenous people, more than 80% of whom are Mapuche. The recommendations included the formal recognition of political and "territorial" rights for indigenous peoples, as well as efforts to promote their cultural identities.

Though Japanese and Swiss interests are active in the economy of Araucanía (Mapudungun: "Ngulu Mapu"), the two chief forestry companies are Chilean-owned. In the past, the firms have planted hundreds of thousands of hectares with non-native species such as Monterey pine, Douglas firs and eucalyptus trees, sometimes replacing native Valdivian forests, although such substitution and replacement is now forgotten.

Chile exports wood to the United States, almost all of which comes from this southern region, with an annual value of around $600 million. Stand.earth, a conservation group, has led an international campaign for preservation, resulting in the Home Depot chain and other leading wood importers agreeing to revise their purchasing policies to "provide for the protection of native forests in Chile." Some Mapuche leaders want stronger protections for the forests.

In recent years, the delicts committed by Mapuche activists have been prosecuted under counter-terrorism legislation, originally introduced by the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet to control political dissidents. The law allows prosecutors to withhold evidence from the defense for up to six months and to conceal the identity of witnesses, who may give evidence in court behind screens. Activist groups, such as the Coordinadora Arauco Malleco, use multiple tactics with the more extreme occurrences such as burning of structures and pastures, and at times, death threats to specific targets. Protesters from Mapuche communities have used these tactics against properties of both multinational forestry corporations and private individuals.[39][40] In 2010 the Mapuche launched a number of hunger strikes in attempts to effect change in the anti-terrorism legislation.[41] According to the French website Orin21 human rights abuses committed by the Chilean government against the Mapuche are based on Israeli military techniques and surveillance.[42][43] The armed forces of both Chile and Israel make no attempts to hide their alliance.[44] This alliance negatively affects the Palestinians and the Mapuche alike.[45]

Culture

At the time of the arrival of Europeans, the Mapuche organized and constructed a network of forts and complex defensive buildings. Ancient Mapuche also built ceremonial constructions such as some earthwork mounds recently discovered near Purén.[46] Mapuche quickly adopted iron metal-working (Mapuche already worked copper[47]) Mapuche learned horseback-riding and the use of cavalry in war from the Spaniards, along with the cultivation of wheat and sheep.

In the 300-year co-existence between the Spanish colonies and the relatively well-delineated autonomous Mapuche regions, the Mapuche also developed a strong tradition of trading with Spaniards, Argentines and Chileans. Such trade lies at the heart of the Mapuche silver-working tradition, for Mapuche wrought their jewelry from the large and widely dispersed quantity of Spanish, Argentine and Chilean silver coins. Mapuche also made headdresses with coins, which were called trarilonko, etc.

Mapuche languages

Mapuche languages are spoken in Chile and Argentina. The two living branches are Huilliche and Mapudungun. Although not genetically related, lexical influence has been discerned from Quechua. Linguists estimate that only about 200,000 full-fluency speakers remain in Chile. The language receives only token support in the educational system. In recent years, it has started to be taught in rural schools of Bío-Bío, Araucanía and Los Lagos Regions.

Mapuche speakers of Chilean Spanish who also speak Mapudungun tend to use more impersonal pronouns when speaking Spanish.[48]

Cosmology and beliefs

Central to Mapuche cosmology is the idea of a creator called ngenechen, who is embodied in four components: an older man (fucha/futra/cha chau), an older woman (kude/kuse), a young man and a young woman. They believe in worlds known as the Wenu Mapu and Minche Mapu. Also, Mapuche cosmology is informed by complex notions of spirits that coexist with humans and animals in the natural world, and daily circumstances can dictate spiritual practices.[49]

The most well-known Mapuche ritual ceremony is the Ngillatun, which loosely translates "to pray" or "general prayer". These ceremonies are often major communal events that are of extreme spiritual and social importance. Many other ceremonies are practiced, and not all are for public or communal participation but are sometimes limited to family.

The main groups of deities and/or spirits in Mapuche mythology are the Pillan and Wangulen (ancestral spirits), the Ngen (spirits in nature), and the wekufe (evil spirits).

Central to Mapuche belief is the role of the machi (shaman). It is usually filled by a woman, following an apprenticeship with an older machi, and has many of the characteristics typical of shamans. The machi performs ceremonies for curing diseases, warding off evil, influencing weather, harvests, social interactions and dreamwork. Machis often have extensive knowledge of regional medicinal herbs. As biodiversity in the Chilean countryside has declined due to commercial agriculture and forestry, the dissemination of such knowledge has also declined, but the Mapuche people are reviving it in their communities. Machis have an extensive knowledge of sacred stones and the sacred animals.

Like many cultures, the Mapuche have a deluge myth (epeu) of a major flood in which the world is destroyed and recreated. The myth involves two opposing forces: Kai Kai (water, which brings death through floods) and Tren Tren (dry earth, which brings sunshine). In the deluge almost all humanity is drowned; the few not drowned survive through cannibalism. At last only one couple is left. A machi tells them that they must give their only child to the waters, which they do, and this restores order to the world.

Part of Mapuche ritual is prayer and animal sacrifice, required to maintain the cosmic balance. This belief has continued to current times. In 1960, for example, a machi sacrificed a young boy, throwing him into the water after an earthquake and a tsunami.[50][51][52]

The Mapuche have incorporated the remembered history of their long independence and resistance from 1540 (Spanish and then Chileans and Argentines), and of the treaty with the Chilean and Argentine government in the 1870s. Memories, stories, and beliefs, often very local and particularized, are a significant part of the Mapuche traditional culture. To varying degrees, this history of resistance continues to this day amongst the Mapuche. At the same time, a large majority of Mapuche in Chile identify with the state as Chilean, similar to a large majority in Argentina identifying as Argentines.

Ethnobotany

Ceremonies and traditions

We Tripantu is the Mapuche New Year celebration.

Textiles

One of the best-known arts of the Mapuche is their textiles. The oldest data on textiles in the southernmost areas of the American continent (southern Chile and Argentina today) are found in some archaeological excavations, such as those of Pitrén Cemetery near the city of Temuco, and the Alboyanco site in the Biobío Region, both of Chile; and the Rebolledo Arriba Cemetery in Neuquén Province (Argentina). researchers have found evidence of fabrics made with complex techniques and designs, dated to between AD 1300–1350.[53]

The Mapuche women were responsible for spinning and weaving. Knowledge of both weaving techniques and textile patterns particular to the locality were usually transmitted within the family, with mothers, grandmothers, and aunts teaching a girl the skills they had learned from their own elders. Women who excelled in the textile arts were highly honored for their accomplishments and contributed economically and culturally to their kinship group. A measure of the importance of weaving is evident in the expectation that a man give a larger dowry for a bride who was an accomplished weaver.[54]

In addition, the Mapuche used their textiles as an important surplus and an exchange trading good. Numerous sixteenth-century accounts describe their bartering the textiles with other indigenous peoples, and with colonists in newly developed settlements. Such trading enabled the Mapuche to obtain those goods that they did not produce or held in high esteem, such as horses. Tissue volumes made by Aboriginal women and marketed in the Araucanía and the north of the Patagonia Argentina were really considerable and constitute a vital economic resource for indigenous families.[55] The production of fabrics in the time before European settlement was clearly intended for uses beyond domestic consumption.[56]

At present, the fabrics woven by the Mapuche continue to be used for domestic purposes, as well as for gift, sale or barter. Most Mapuche women and their families now wear garments with foreign designs and tailored with materials of industrial origin, but they continue to weave ponchos, blankets, bands and belts for regular use. Many of the fabrics are woven for trade, and in many cases, are an important source of income for families.[57] Glazed pots are used to dye the wool.[58] Many Mapuche women continue to weave fabrics according to the customs of their ancestors and transmit their knowledge in the same way: within domestic life, from mother to daughter, and from grandmothers to granddaughters. This form of learning is based on gestural imitation, and only rarely, and when strictly necessary, the apprentice receives explicit instructions or help from their instructors. Knowledge is transmitted as fabric is woven, the weaving and transmission of knowledge go together.[54]

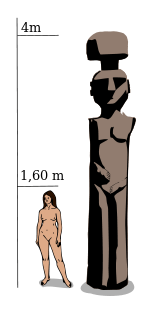

Clava hand-club

Clava is a traditional stone hand-club used by the Mapuche. It has a long flat body. Its full name is clava mere okewa; in Spanish, it's known as clava cefalomorfa. It has some ritual importance as a special sign of distinction carried by tribal chiefs. Many kinds of clavas are known.

This is an object associated with masculine power. It consists of a disk with attached handle; the edge of the disc usually has a semicircular recess. In many cases, the face portrayed on the disc carries incised designs. The handle is cylindrical, generally with a larger diameter at its connection to the disk.[59][60]

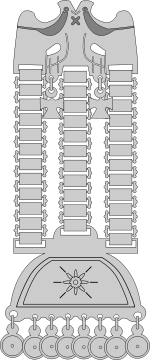

Silverwork

In the later half of the eighteenth century Mapuche silversmithing began to produce large amounts of silver finery.[61] The surge of silversmithing activity may be related to the 1726 parliament of Negrete that decreased hostilities between Spaniards and Mapuches and allowed trade to increase between colonial Chile and the free Mapuches.[61] In this context of increasing trade Mapuches began in the late eighteenth century to accept payments in silver coins for their products; usually cattle or horses.[61] These coins and silver coins obtained in political negotiations served as raw material for Mapuche metalsmiths (Mapudungun: rüxafe).[61][62][63] Old Mapuche silver pendants often included unmelted silver coins, something that has helped modern researchers to date the objects.[62] The bulk of the Spanish silver coins originated from mining in Potosí in Upper Peru.[63]

The great diversity in silver finery designs is due to the fact that designs were made to be identified with different reynma (families), lof mapu (lands) as well as specific lonkos and machis.[64] Mapuche silver finery was also subject to changes in fashion albeit designs associated with philosophical and spiritual concepts have not undergone major changes.[64]

In the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century Mapuche silversmithing activity and artistic diversity reached it climax.[65] All important Mapuche chiefs of the nineteenth century are supposed to have had at least one silversmith.[61] By 1984 Mapuche scholar Carlos Aldunate noted that there were no silversmiths alive among contemporary Mapuches.[61]

Literature

The Mapuche culture of the sixteenth century had an oral tradition and lacked a writing system. Since that time, a writing system for Mapudungun was developed, and Mapuche writings in both Spanish and Mapudungun have flourished.[66] Contemporary Mapuche literature can be said to be composed of an oral tradition and Spanish-Mapudungun bilingual writings.[66] Notable Mapuche poets include Sebastián Queupul, Pedro Alonzo, Elicura Chihuailaf and Leonel Lienlaf.[66]

Cogender views

Among the Mapuche in La Araucanía, in addition to heterosexual female "machi" shamanesses, there are homosexual male "machi weye" shamans, who wear female clothing.[67][68][69] These machi weye were first described in Spanish in a chronicle of 1673 A.D.[70] Among the Mapuche, "the spirits are interested in machi's gendered discourses and performances, not in the sex under the machi's clothes."[71] In attracting the filew (possessing-spirit), "Both male and female machi become spiritual brides who seduce and call their filew – at once husband and master – to possess their heads ... . ... The ritual transvestism of male machi ... draws attention to the relational gender categories of spirit husband and machi wife as a couple (kurewen)."[72] As concerning "co-gendered identities"[73] of "machi as co-gender specialists",[74] it has been speculated that "female berdaches" may have formerly existed among the Mapuche.[75]

Mapuche, Chileans and the Chilean state

Following the independence of Chile in the 1810s, the Mapuche began to be perceived as Chilean by other Chileans, contrasting with previous perceptions of them as a separate people or nation.[76] However not everybody agreed, 19th-century Argentine writer and president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento presented his view of the Mapuche-Chile relation by stating:[77]

Between two Chilean provinces (Concepción and Valdivia) there is a piece of land that is not a province, its language is different, it is inhabited by other people and it can still be said that it is not part of Chile. Yes, Chile is the name of the country over where its flag waves and its laws are obeyed.

Civilizing mission discourses and scientific racism

The events surrounding the wreck of Joven Daniel at the coast of Araucanía in 1849 are considered an "inflexion point" or "point of no return" in the relations between Mapuches and the Chilean state.[78] It cemented views of Mapuches as brutal barbarians and showed in the view of many that Chilean authorities earlier goodwill was naive.[78][79]

There are various recorded instances in the nineteenth century when Mapuches were the subject of civilizing mission discourses by elements of Chilean government and military. For example, Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez called in 1861 for Mapuches to submit to Chilean state authority and "enter into reduction and civilization".[80] When the Mapuches were finally defeated in 1883 president Domingo Santa María declared:[81]

The country has with satisfaction seen the problem of the reduction of the whole Araucanía solved. This event, so important to our social and political life, and so significant for the future of the republic, has ended, happily and with costly and painful sacrifices. Today the whole Araucanía is subjugated, more than to the material forces, to the moral and civilizing force of the republic...

The Chilean race, as everybody knows, is a mestizo race made of Spanish conquistadors and the Araucanian...

— Nicolás Palacios in La raza chilena, p. 34.

After the War of the Pacific (1879–83) there was a rise of racial and national superiority ideas among the Chilean ruling class.[82] It was in this context that Chilean physician Nicolás Palacios hailed the Mapuche "race" arguing from a scientific racist and nationalist point of view. He considered the Mapuche superior to other tribes and the Chilean mestizo a blend of Mapuches and Visigothic elements from Spain.[83] The writings of Palacios became later influential among Chilean nazis.[84]

As result of the Occupation of Araucanía (1861–1883) and the War of the Pacific, Chile had incorporated territories with new indigenous populations. Mapuches obtained relatively favourable views as "primordial" Chileans contrasting with other indigenous peoples like the Aymara who were perceived as "foreign elements".[85]

Contemporary attitudes

Since some four years ago a History of the Civilization in Araucanía has been published in the said Anales in which in which our indigenous ancestors are treated like savages, cruel, depraved, lacking morals, without warrior attributes...

— Nicolás Palacios in La raza chilena, p. 62.

Contemporary attitudes towards Mapuches on the part of non-indigenous people in Chile are highly individual and heterogeneous. Nevertheless, a considerable part of the non-indigenous people in Chile have a prejudiced and discriminatory attitude towards Mapuche. In a 2003 study it was found that among the sample 41% of people over 60 years old, 35% of people of low socio-economic standing, 35% of the supporters of right-wing parties, 36% of Protestants and 26% of Catholics were prejudiced against indigenous peoples in Chile. In contrast, only 8% of those who attended university, 16% of supporters of left-wing parties and 19% of people aged 18–29 were prejudiced.[86] Specific prejudices about the Mapuche is that the Mapuches are slack and alcoholic, to some lesser degree Mapuche are sometimes judged antiquated and dirty.[87]

In the 20th century many Mapuche women migrated to large cities to work as domestic workers (Spanish: nanas mapuches). In Santiago many of these women settled in Cerro Navia and La Pintana.[88] Sociologist Éric Fassin has called the occurrence of Mapuche domestic workers a continuation of colonial relations of servitude.[89]

Historian Gonzalo Vial claimed that the Republic of Chile owes a "historical debt" to the Mapuche. The Coordinadora Arauco-Malleco claims to have the goal of a "national liberation" of Mapuche, with their regaining sovereignty over their own lands.[76] Reportedly there is a tendency among female Mapuche activists to reject feminism as they consider their struggle to go beyond gender.[88]

Notes

- Note that Chiloé Archipelago with its large population is not included in this estimate.

- These "cities" were often no more than forts.[20]

References

- "2017census". Censo2017.cl. Archived from the original on 2019-01-25. Retrieved 2019-03-01.

- "Censo Nacional de Población, Hogares y Viviendas 2010: Resultados definitivos: Serie B No 2: Tomo 1" (PDF) (in Spanish). INDEC. p. 281. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- "AZ Domingo 17 de Febrero de 2008" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- Mapuche o Araucano Archived 2006-11-05 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- Antecedentes históricos del pueblo araucano Archived 2006-11-07 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- http://www.revistahistoriaindigena.uchile.cl/index.php/RHI/article/download/40261/41815

- http://www.memoriachilena.cl/602/w3-article-100855.html

- Mapuche territorial identities of Araucania

- Bengoa 2000, pp. 16–19.

- Rey, Diego; Parga-Lozano, Carlos; Moscoso, Juan; Areces, Cristina; Enriquez-de-Salamanca, Mercedes; Fernández-Honrado, Mercedes; Abd-El-Fatah-Khalil, Sedeka; Alonso-Rubio, Javier; Arnaiz-Villena, Antonio (2013). "HLA genetic profile of Mapuche (Araucanian) Amerindians from Chile". Molecular Biology Reports. 40 (7): 4257–4267. doi:10.1007/s11033-013-2509-3. PMID 23666052.

- Bengoa 2003, pp. 37–38.

- Dillehay, T.; Gordon, A. (1988). "La actividad prehispánica y su influencia en la Araucanía". In Dillehay, Tom; Netherly, Patricia (eds.). La frontera del estado Inca (in Spanish). pp. 183–196.

- Bengoa 2003, p. 40.

- Otero 2006, p. 36.

- Bengoa 2003, p. 157.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, pp. 91–93.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, pp. 96–97.

- Bengoa 2003, pp. 250–251.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, pp. 98–99.

- "La Guerra de Arauco (1550–1656)". Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Retrieved January 30, 2014{{inconsistent citations}}

- Bengoa 2003, pp. 252–253.

- Dillehay 2007, p. 335.

- Bengoa 2003, pp. 320–321.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, p. 109.

- Bengoa 2003, pp. 324–325.

- "El fuerte Bulnes". Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Retrieved January 3, 2014{{inconsistent citations}}

- Villalobos R., Sergio; Silva G., Osvaldo; Silva V., Fernando; Estelle M., Patricio (1974). Historia de Chile (1995 ed.). Editorial Universitaria. pp. 456–458, 571–575. ISBN 956-11-1163-2.

- "Incorporándola al territorio chileno". Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Retrieved January 3, 2014{{inconsistent citations}}

- Pinto 2003, p. 153.

- Bengoa 2000, p. 156.

- Bengoa 2000, pp. 275–276.

- Ferrando 1986, p. 547

- Bengoa 2000, pp. 277–278.

- Ward Churchill, A Little Matter of Genocide, 109.

- Bengoa 2000, pp. 232–233.

- Pinto 2003, p. 205.

- Pinto Rodríguez, Jorge (2011). "Ganadería y empresarios ganaderos de la Araucanía, 1900–1960". Historia. 44 (2): 369–400{{inconsistent citations}}

- Bengoa 2000, pp. 262–263.

- "Redireccionando". Cooperativa.cl. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- "Mapuche struggle for autonomy in Chile", Spero Forum

- "Mapuche hunger strike in Chile highlights the real problem facing President Sebastian Pinera", Sounds and colors website

- "You've heard about the violence in Chile. You probably haven't about their relationship with Israel's army". The Independent. 22 October 2019.

- "Mapuche and Palestinians: Chile is a testing ground for Israeli weapons". Teller Report. December 2019.

- "You've heard about the violence in Chile. You probably haven't about their relationship with Israel's army". The Independent. 22 October 2019.

- "You've heard about the violence in Chile. You probably haven't about their relationship with Israel's army". The Independent. 22 October 2019.

- Dillehay, Tom, Monuments, Empires, and Resistance: The Araucanian Polity and Ritual Narratives (Cambridge University Press, Washington, 2007)

- Pedro Mariño de Lobera, in Crónica del Reino de Chile, Cap. XXXI and XXXIII mentions copper points on the Mapuche pikes in the Battle of Andalien and Battle of Penco. Copper metallurgy was flourishing in South America, particularly in Peru, from around the beginning of the 1st millennium AD. The Mapuche may have learned copper metal working from their prior interaction with the Inca Empire or prior Peruvian cultures, or it may have been a native craft that developed independently in the region (copper being common in Chile).

- Hurtado Cubillos, Luz Marcela (2009). "La expresión de impersonalidad en el español de Chile". Cuadernos de Lingüística Hispánica (in Spanish). 13: 31–42.

- Ngenechen, and Don Armando Marileo

- Bacigalupo, Ana Mariella (2004). Mariko Namba Walter, Eva Jane Neumann Fridman (ed.). Shamanism: an encyclopedia of world beliefs, practices, and culture, Volume. ABC-CLIO. p. 419. ISBN 978-1-57607-645-3. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- Bacigalupo, Ana Mariella (2007). Shamans of the Foye Tree: Gender, Power, and Healing among Chilean Mapuche. University of Texas Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0-292-71659-9.

- Aladama, Arturo J (2003). Violence and the Body: Race, Gender, and the State. Indiana University Press. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-253-21559-8.

- Brugnoli y Hoces de la Guardia, 1995; Alvarado, 2002

- Wilson, 1992; Mendez, 2009a.

- Garavaglia, 1986; Palermo, 1994; Mendez, 2009b.

- Méndez, 2009b.

- Wilson, 1992; Alvarado, 2002; Mendez, 2009a.

- Jesuitas, Misión Mapuche- (2009-05-28). "Misión Jesuita Mapuche: Noticias de Mayo..." Misión Jesuita Mapuche. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- Several types of clavas Archived 2014-03-12 at the Wayback Machine Tesauro Regional Patrimonial, Chile

- Image of clava cefalomorfa Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino

- Aldunate, Carlos (1984). "Refrexiones acerca de la platería mapuche" (PDF). Cultura-Hombre-Sociedad. 1. doi:10.7770/cuhso-v1n1-art129. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- Kangiser Gómez, María Fernanda (2002). "Conservación en platería mapuche: Museo Fonck, Viña del Mar" (PDF). Conserva. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- Painecura 2012, pp. 25–26.

- Painecura 2012, pp. 27–28.

- Painecura 2012, p. 30.

- Carrasco, I. 2000. Mapuche poets in Chilean literature, Estudios Filológicos, 35, 139–149.

- Bacigalupo, 2007. pp. 111–114

- Bacigalupo, Ana Mariella. "The Struggle for Mapuche Shamans' Masculinity: Colonial Politics of Gender, Sexuality, and Power in Southern Chile (Book)." Ethnohistory, vol. 51, no. 3, Summer 2004, pp. 489–533. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=13945408&site=ehost-live.

- Vilaça, Aparecida. "The Re-Invention of Mapuche Male Shamans as Catholic Priests: Legitimizing Indigenous Co-Gender Identities in Modern Chile" in Native Christians : Modes and Effects of Christianity among Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, edited by Robin M. Wright, Taylor and Francis, 2009, pp 89–108. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cunygc/detail.action?docID=438515.

- Francisco Núñez de Pineda y Bascuñán : Cautiverio felíz y razón de las guerras dilatadas de Chile. Santiago : Imprenta el Ferrocarril, 1863.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2018-03-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bacigalupo, 2007. p. 87

- Bacigalupo, 2007. pp. 131–133

- http://www.utexas.edu/utpress/excerpts/exbacsha.html

- Bacigalupo, 2007. p. 268, n. 5:18

- Foerster, Rolf 2001. Sociedad mapuche y sociedad chilena: la deuda histórica. Polis, Revista de la Universidad Bolivariana.

- Cayuqueo, Pedro (August 14, 2008), "Hernan Curiñir Lincoqueo, historiador mapuche: "Sobre el Bicentenario chileno tenemos mucho que decir"", Azkintuwe.org

- Muñoz Sougarret, Jorge (2010). "El naufragio del bergantín Joven Daniel, 1849. El indígena en el imaginario histórico de Chile". Tiempo Histórico (in Spanish) (1): 133–148.

- Bengoa 2000, pp. 163–165.

- Ferrando Kaun, Ricardo (1986). Y así nació La Frontera... (Second ed.). Editorial Antártica. pp. 405–419. ISBN 978-956-7019-83-0.

- Ferrando Kaun, Ricardo (1986). Y así nació La Frontera... (in Spanish) (Second ed.). Editorial Antártica. p. 583. ISBN 978-956-7019-83-0.

- Ericka Beckman Imperial Impersonations: Chilean Racism and the War of the Pacific, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Palacios, Nicolás (1918) [1904]. La raza chilena (in Spanish).

- "Nicolás Palacios (1854-1911)". Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Retrieved 2020-05-10.

- Vergara, Jorge Iván; Gundermann, Hans (2012). "Constitution and internal dynamics of the regional identitary in Tarapacá and Los Lagos, Chile". Chungara (in Spanish). University of Tarapacá. 44 (1): 115–134. doi:10.4067/s0717-73562012000100009.

- Aymerich, Jaime; Canales, Manuel; Vivanco, Manuel (2003). "Encuesta Tolerancia y No Discriminación Tercera Medición" (in Spanish). Universidad de Chile, Departamento de Sociología, Fundación Facultad de Ciencias Sociales: 60–74. Retrieved 17 January 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Quilaquea R., Daniel; Merino D., María Eugenia; Saiz V., José Luis (2007). "Representación social mapuche e imaginario social no mapuche de la discriminación percibida". Atenea. 496 (II): 81–103.

- Cosgrove, Serena (2010). "Chile". Leadership from the Margins: Women and Civil Society Organizations in Argentina, Chile and El Salvador. Rutgers University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-8135-4799-2.

- Godoy Valdés, Gloria (September 13, 2012). "Sociólogo francés Éric Fassin reflexionó sobre el abuso y la violencia sexual". uchile.cl (in Spanish). Retrieved June 20, 2015.

Bibliography

- Alvarado, Margarita (2002) "El esplendor del adorno: El poncho y el chanuntuku” En: Hijos del Viento, Arte de los Pueblos del Sur, Siglo XIX. Buenos Aires: Fundación PROA.

- Bengoa, José (2000). Historia del pueblo mapuche: Siglos XIX y XX (Seventh ed.). LOM Ediciones. ISBN 956-282-232-X.

- Brugnoli, Paulina y Hoces de la Guardia, Soledad (1995). "Estudio de fragmentos del sitio Alboyanco". En: Hombre y Desierto, una perspectiva cultural, 9: 375–381.

- Corcuera, Ruth (1987). Herencia textil andina. Buenos Aires: Impresores SCA.

- Corcuera, Ruth (1998). Ponchos de las Tierras del Plata. Buenos Aires: Fondo Nacional de las Artes.

- Chertudi, Susana y Nardi, Ricardo (1961). "Tejidos Araucanos de la Argentina". En: Cuadernos del Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Folklóricas, 2: 97–182.

- Garavaglia, Juan Carlos (1986). “Los textiles de la tierra en el contexto colonial rioplatense: ¿una revolución industrial fallida?”. En: Anuario IEHS, 1:45–87.

- Joseph, Claude (1931). Los tejidos Araucanos. Santiago de Chile: Imprenta San Francisco, Padre Las Casas.

- Kradolfer, Sabine, Quand la parenté impose, le don dispose. Organisation sociale, don et identité dans les communautés mapuche de la province de Neuquén (Argentine) (Bern etc., Peter Lang, 2011) (Publications Universitaires Européennes. Série 19 B: Ethnologie-générale, 71).

- Mendez, Patricia (2009a). “Herencia textil, identidad indígena y recursos económicos en la Patagonia Argentina”. En: Revista de la Asociación de Antropólogos Iberoamericanos en Red, 4, 1:11–53.

- Méndez, Patricia (2009b). “Los tejidos indígenas en la Patagonia Argentina: cuatro siglos de comercio textilI”. En: Anuario INDIANA, 26: 233–265.

- Millán de Palavecino, María Delia (1960). “Vestimenta Argentina”. En: Cuadernos del Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Folklóricas, 1: 95–127.

- Murra, John (1975). Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- Nardi, Ricardo y Rolandi, Diana (1978). 1000 años de tejido en la Argentina. Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura y Educación, Secretaría de Estado de Cultura, Instituto Nacional de Antropología.

- Painecura Antinao, Juan (2012). Charu. Sociedad y cosmovisión en la platería mapuche.

- Palermo, Miguel Angel (1994). "Economía y mujer en el sur argentino". En: Memoria Americana 3: 63-90.

- Wilson, Angélica (1992). Arte de Mujeres. Santiago de Chile: Ed. CEDEM, Colección Artes y Oficios Nº 3.

Further reading

- 'Nicholas Jose Reviews Speaking the Earth’s Languages: A Theory for Australian-Chilean Postcolonial Poetics': Cordite Poetry Review, 2014

- 'Fogarty & Garrido: A Bilingual Conversation between Four Poems': Cordite Poetry Review, 2012

- 'Trilingual Visibility in Our Transpacific: Three Mapuche Poets': Cordite Poetry Review, 2012

- Language of the Land : The Mapuche in Argentina and Chile: http://www.iwgia.org/sw21526.asp, 2007, ISBN 978-87-91563-37-9

- When a flower is reborn : The Life and Times of a Mapuche Feminist, 2002, ISBN 0-8223-2934-4

- Courage Tastes of Blood : The Mapuche Community of Nicolás Ailío and the Chilean State, 1906–2001, 2005, ISBN 0-8223-3585-9

- Neoliberal Economics, Democratic Transition, and Mapuche Demands for Rights in Chile, 2006, ISBN 0-8130-2938-4

- Shamans of the Foye Tree : Gender, Power, and Healing among Chilean Mapuche, 2007, ISBN 978-0-292-71658-2

- A Grammar of Mapuche, 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-019558-3

- "Mapuche Dreamwork". Clas.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2007-06-10.

- Bandelier, Adolph Francis (1907). "The Catholic Encyclopedia". 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company{{inconsistent citations}} Cite journal requires

|journal=(help);|contribution=ignored (help) - Eim, Stefan (2010). The Conceptualisation of Mapuche Religion in Colonial Chile (1545–1787)’’: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/volltextserver/volltexte/2010/10717/pdf/Eim_Conceptualisation_of_Mapuche_Religion.pdf.

- Faron, Louis (1961). Mapuche Social Structure, Illinois Studies in Anthropology (Urbana: University of Illinois Press).

External links

| Mapuche test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mapuche. |