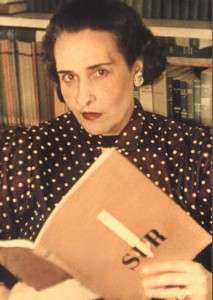

Victoria Ocampo

Victoria Ocampo CBE (7 April 1890 – 27 January 1979) was an Argentine writer and intellectual, described by Jorge Luis Borges as La mujer más argentina ("The quintessential Argentine woman"). Best known as an advocate for others and as publisher of the literary magazine Sur, she was also a writer and critic in her own right and one of the most prominent South American women of her time. Her sister Silvina Ocampo, also a writer, was married to Adolfo Bioy Casares.

Victoria Ocampo CBE (honorary) | |

|---|---|

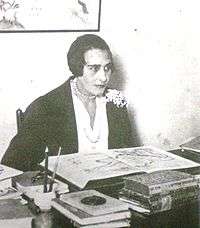

Victoria Ocampo, 1931 | |

| Born | Ramona Victoria Epifanía Rufina Ocampo 7 April 1890 |

| Died | 27 January 1979 (aged 88) Béccar, Argentina |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Occupation | Writer, intellectual |

Biography

Born Ramona Victoria Epifanía Rufina Ocampo in Buenos Aires into a high-society family, she was educated at home by a French governess. She later wrote: "the alphabet-book in which I learned to read was French, as was the hand that taught me to draw those first letters."[1][2]

She is sometimes said to have attended the Sorbonne: on page 39 of her biography of Ocampo, Doris Meyer states that, during the family's 1906–1907 trip to Paris, the same during which she was etched by Paul César Helleu, the Ocampos allowed 17-year-old Victoria, "well-chaperoned", to audit some lectures at the Sorbonne and at the Collège de France. She remembered particularly enjoying Henri Bergson's lectures at the latter. She never matriculated at either. Her old traditional wealthy family frowned on formal education for women, so Victoria had little. In 1912, Ocampo married Bernando de Estrada (also known as Monaco Estrada). The marriage was not happy; the couple separated in 1920, and Ocampo began a long–lasting affair with her husband's cousin Julián Martínez, a diplomat.[3][2]

In Buenos Aires, she was a lynchpin of the intellectual scene of the 1920s and 1930s. Her first book, written in French, was De Francesca à Beatrice (c. 1923), a commentary on Dante's Divine Comedy. Other works include Domingos en Hyde Park; El Hamlet de Laurence Olivier; Emily Brontë (Terra incógnita); a series called Testimonios (ten volumes); Virginia Woolf, Orlando y Cía; San Isidro; 338171 T.E. (Lawrence of Arabia) (a biography of T. E. Lawrence) and a posthumously published autobiography. There is also an edited book of dialogues between Ocampo and Jorge Luis Borges.[2]

Ocampo corresponded with Virginia Woolf in the later 1930s; the two writers met in London in June 1939 but the meeting was not a success.[4]

Perhaps of greater significance than her own writing, she was founder (1931) and publisher of the magazine Sur, the most important literary magazine of its time in Latin America. Among the writers published in Sur were Borges, Ernesto Sabato, Adolfo Bioy Casares, Julio Cortázar, José Ortega y Gasset, Manuel Peyrou, Albert Camus, Enrique Anderson Imbert, José Bianco, Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Waldo Frank, Gabriela Mistral, Eduardo Mallea, and her own younger sister Silvina Ocampo.[5]

In 1935, Ocampo expressed some approval for Benito Mussolini with whom she was granted an interview in March of that year in Rome, hailing him then as "genius" and Caesar reborn.[6] "I have seen Italy in blossom turn its face towards him."[7] However, she was never a convinced fascist sympathizer, and expressed disapproval of Mussolini's conservative views on gender roles and the regime's growing militarism.[8] By the time her interview with Mussolini was published in August 1936, Italy had invaded Abyssinia and Ocampo appended a note to it declaring that any hope that the fascist regime might improve was lost and criticized those in Argentina who supported Italy's belligerence.[9]

In 1937, Ocampo and the editors of Sur came out openly against fascism and definitively linked the journal with liberalism.[10] During the Spanish Civil War, the magazine sided with the Republicans.[11] She supported and edited from Argentina, in collaboration with her friend and translator Pelegrina Pastorino, the anti-Nazi magazine Les Lettres Francaises, directed by Roger Caillois; and in 1946 she was the only Argentine who attended the Nuremberg Trials. A few months before World War II, in 1939, Ocampo was appointed to the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations, but did not participate in its works.[12] In 1953, she was briefly imprisoned for her open opposition to the government of Juan Domingo Perón.[13]

Ocampo was made a member of the Argentine Academy of Letters in 1976 (the first woman ever admitted to the Academy); she formally took her seat on 23 June 1977. The "cultural dialog", initiated in 1977 by the de facto government but organized by UNESCO, was held in her home, Villa Ocampo, in San Isidro, Buenos Aires Province; she eventually donated the house to UNESCO in 1973.[14][15]

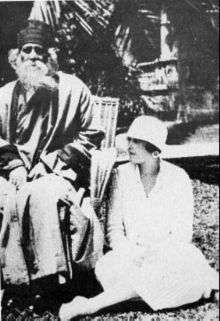

At Villa Ocampo, her guests included Igor Stravinsky, André Malraux and Rabindranath Tagore had been her guests, also Indira Gandhi, José Ortega y Gasset, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Ernest Ansermet and Rafael Alberti. Graham Greene dedicated his 1973 novel The Honorary Consul to her, "with love, and in memory of the many happy weeks I have passed at San Isidro and Mar del Plata".

Victoria Ocampo died in Buenos Aires in 1979, and is buried in La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires.[16]

Honors

- Maria Moors Cabot prize

- Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Doctor honoris causa – Harvard University, Columbia University

- Premio de Honor de la SADE

- Gold Medal – Académie française

Biopics

- Her life was portrayed in a film for TV in 1984 "Four Faces of Victoria", directed by Oscar Barney Finn with four actresses playing the different ages of Victoria (Carola Reyna, Nacha Guevara, Julia von Grolman and China Zorrilla).[17]

- Her attitude and political views were depicted in Monica Ottino's theater play Eva and Victoria, an imaginary confrontation between the young Eva Perón and the elderly Victoria. The play ran successfully during the eighties with Soledad Silveyra as Eva and China Zorrilla as Victoria.[18]

Notes

- Scarzanella, Eugenia; Schpun, Mônica Raisa. Sin fronteras: encuentros de mujeres y hombres entre América Latina y Europa, siglos XIX-XX. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Victoria Ocampo's Chronology, villaocampo.org; accessed 25 December 2016.

- Bausset, Ana Margarita. Evolucion de la Autobiografia Contemporanea en El Cono Sur: Victoria Ocampo, Jose Donoso E Isabel Allende. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Nigel Nicolson, ed., The Letters of Virginia Woolf, London, Hogarth Press, 1975-80, letters 3128, 3304, 3445, 3450, 3453, 3477, 3478, 3516, 3528.

- "VICTORIA OCAMPO, IMPORTANTE COLECCION - (ARCHIVE - A RARE LOT of 210 items) - Lote de 210 ejemplares: libros firmados, primeras ediciones, revistas Sur, traducciones, notas periodísticas y libros sobre la escritora más importante de la Argentina". iberlibro.com. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- Victoria Ocampo, "Living History", in Against the Wind and the Tide, ed. Doris Meyer, University of Texas Press, Austin, TX, 1990, p. 217

- Victoria Ocampo, "Living History", in Against the Wind and the Tide, ed. Doris Meyer, University of Texas Press, Austin, TX, 1990, p. 222

- Rogers, Gayle (2014). Modernism and the New Spain: Britain, Cosmopolitan Europe, and Literary History. Oxford University Press. pp. 140–141.

- Rogers, Gayle (2014). Modernism and the New Spain: Britain, Cosmopolitan Europe, and Literary History. Oxford University Press. p. 258.

- Strong, Beret E. (1997). The Poetic Avant-garde: The Groups of Borges, Auden, and Breton. Northwestern University Press. pp. 108–111.

- Strong, Beret E. (1997). The Poetic Avant-garde: The Groups of Borges, Auden, and Breton. Northwestern University Press. p. 98.

- Grandjean, Martin (2018). Les réseaux de la coopération intellectuelle. La Société des Nations comme actrice des échanges scientifiques et culturels dans l'entre-deux-guerres [The Networks of Intellectual Cooperation. The League of Nations as an Actor of the Scientific and Cultural Exchanges in the Inter-War Period] (in French). Lausanne: Université de Lausanne. p. 290.

- Vázquez, María Esther. Victoria Ocampo: El Mundo Como Destino. Seix Barral. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "La mansión donde Victoria Ocampo aún está presente festeja sus 125 años" (in Spanish). Clarín. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- "Victoria Ocampo y la UNESCO" (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- "Famosos". cementeriorecoleta.com.ar. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "Oscar Barney-Finn". fundacionfirstteam.org. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- "Eva y Victoria". diversica.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

References

- Chiappini, Julio: Victoria Ocampo. Biografía, Rosario, Editorial Fas, 2012; 2 vol.

- Meyer, Doris: Victoria Ocampo: Against the Wind and the Tide (Texas Pan-American Series paperback, University of Texas Press, reprint edition, 1990). Originally published New York, George Brazillier, 1978. Re-issue ISBN 0-292-78710-3.

- Dyson, Ketaki Kushari: In Your Blossoming Flower Garden: Rabindranath Tagore and Victoria Ocampo, New Delhi, Sahitya Akademi, 1988; reprinted 1996. ISBN 81-260-0174-7.

- Bassnett, Susan, 1990 (ed.): Knives and Angels: Women Writers in Latin America. London/New Jersey: Zed Books.