Principality of Transylvania (1570–1711)

The Principality of Transylvania (German: Fürstentum Siebenbürgen; Hungarian: Erdélyi Fejedelemség; Latin: Principatus Transsilvaniae; Romanian: Principatul Transilvaniei or Principatul Ardealului; Turkish: Erdel Voyvodalığı or Transilvanya Prensliği) was a semi-independent state, ruled primarily by Hungarian princes.[7][8][9][10][11][12] Its territory, in addition to the traditional Transylvanian lands, also included the other major component called Partium. The establishment of the principality was connected to the Treaty of Speyer.[13][14] However Stephen Báthory's status as king of Poland also helped to phase in the name Principality of Transylvania.[15] It was usually under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire; however, the principality often had dual vassalage (Ottoman Turkish sultans and the Habsburg Hungarian kings) in the 16th and 17th centuries.[16][17]

Principality of Transylvania Principatus Transsilvaniae | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1570–1711 | |||||||||

Top: Báthory banner

Bottom: Bethlen banner Coat of arms

| |||||||||

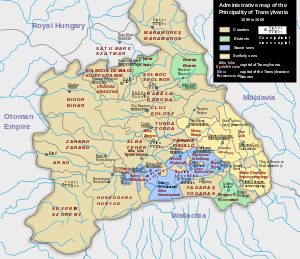

Administrative map of the Principality of Transylvania, 1606-1660 | |||||||||

| Status | Vassal state of the Ottoman Empire; Hungarian Crown Land | ||||||||

| Capital | Alba Iulia (Gyulafehérvár) 1570–1692 Cibinium (Nagyszeben/Hermannstadt/Sibiu) 1692–1711 | ||||||||

| Common languages | Latin (in administration, science and politics), Hungarian (vernacular, language of Diet and legislation[1][2][3][4]), German (vernacular, business, some official functions and instruction), Romanian, Ruthenian (vernacular). | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism, Calvinism, Lutheranism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Greek Catholicism, Unitarianism, Judaism | ||||||||

| Government | Principality, Elective monarchy | ||||||||

| Rulers | |||||||||

• 1570–1571 (first) | John II Sigismund Zápolya | ||||||||

• 1704–1711 (last) | Francis II Rákóczi | ||||||||

| Legislature | Transylvanian Diet | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 1003 | |||||||||

| 16 August 1570 | |||||||||

| 28 September 1604–23 June 1606 | |||||||||

| 23 June 1606 | |||||||||

| 31 December 1621 | |||||||||

| 16 October 1690 | |||||||||

| 26 January 1699 | |||||||||

| 15 June 1703 – 1 May 1711 | |||||||||

• Peace of Szatmár | 29 April 1711 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The principality continued to be a part of the Lands of the Hungarian Crown[18] and was a symbol of the survival of Hungarian statehood.[19] It represented the Hungarian interests against Habsburg encroachments in Habsburg-ruled Kingdom of Hungary.[20] All traditional Hungarian law remained to be followed scrupulously in the principality;[16] furthermore, the state was preponderantly Protestant.[21] After the unsettled period of Rákóczi's War of Independence, it was subordinated within the Habsburg Monarchy.

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early history

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contemporary

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Romania |

|

|

Post-Revolution |

|

|

Background

Eastern Hungarian Kingdom and Zápolya family

On 29 August 1526, the army of Sultan Suleiman of the Ottoman Empire inflicted a decisive defeat on the Hungarian forces at Mohács. John Zápolya was en route to the battlefield with his sizable army but did not participate in the battle for unknown reasons. The youthful King Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia fell in battle, as did many of his soldiers. As Zápolya was elected king of Hungary, Ferdinand from the House of Habsburg also claimed the throne of Hungary. In the ensuing struggle John Zápolya received the support of Sultan Suleiman I, who after Zápolya's death in 1540, occupied Buda and central Hungary in 1541 under the pretext of protecting Zápolya's son, John II. Hungary was now divided into three sections: Royal Hungary in the west and north, Ottoman Hungary, and the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom under Ottoman suzerainty, which later became the Principality of Transylvania, where Austrian and Turkish influences vied for supremacy for nearly two centuries. The Hungarian magnates of Transylvania resorted to a policy of duplicity in order to preserve independence.

Transylvania was administrated by Isabella, John Sigismund's mother, from 1541 to 1551, when it fell for five years under Habsburg rule (1551–1556). The House of Zapolya gained again the control of Transylvania in 1556,[22] when the Diet of Szászsebes elected Sigismund as prince of Transylvania.

Transylvania was now beyond the reach of Catholic religious authority, allowing Lutheran and Calvinist preaching to flourish. In 1563, Giorgio Blandrata was appointed as court physician, and his radical religious ideas increasingly influenced both the young king John II and the Calvinist bishop Francis David,[23] eventually converting both to the Anti-Trinitarian (Unitarian) creed. In a formal public disputation, Francis David prevailed over the Calvinist Peter Melius; resulting in 1568 in the formal adoption of individual freedom of religious expression under the Edict of Torda. This was the first such legal guarantee of religious freedom in Christian Europe, however only for Lutherans, Calvinists, Unitarians and of course Catholics, with the Orthodox Christian confession being "tolerated", with no legal guarantees granted.

Principality of Transylvania

The Principality of Transylvania was established in 1570 when John II renounced his claim as King of Hungary in the Treaty of Speyer (ratified in 1571),[14][24] however he became a Transylvanian prince.[25] The treaty also recognized that Principality of Transylvania belonged to the Kingdom of Hungary in the sense of public law.[26] Upon the death of John II in 1571 the Royal House of Báthory came to power and ruled Transylvania as princes under the Ottomans; and briefly under Habsburg suzerainty, until 1602. Their rise to power marked the beginning of the Principality of Transylvania as a semi-independent state.

Prince Stephen Báthory was the first powerful prince of independent Transylvania,[23] a Hungarian Catholic who later became King under the name Stephen Báthory of Poland,[23] undertook to maintain the religious liberty granted by the Edict of Torda, but interpreted this obligation in an increasingly restricted sense. The latter period of Báthory rule saw Transylvania under Sigismund Báthory – prince of the Holy Roman Empire[23] – enter the Long War, which started as a Christian alliance against the Turks and became a four-sided conflict involving Transylvania, the Habsburgs, the Ottomans, and the voivode of Wallachia, Michael the Brave. After 1601 the Principality for a short time was under the rule of Rudolf I who initiated the Germanization of the population, and in order to reclaim the Principality for Catholicism the Counter Reformation. From 1604 to 1606, the Hungarian nobleman Stephen Bocskay led a successful rebellion against Austrian rule. Bocskay was elected Prince of Transylvania on 5 April 1603 and prince of Hungary two months later. He achieved the Peace of Vienna in 1606.[23] By the Peace of Vienna, Bocskay obtained religious liberty and political autonomy, the restoration of all confiscated estates, the repeal of all "unrighteous" judgments, and a complete retroactive amnesty for all Hungarians in Royal Hungary, as well as his own recognition as independent sovereign prince of an enlarged Principality of Transylvania. By the Treaty of Vienna (1606) was guaranteed the right of Transylvanians to elect their own independent princes, but Georg Keglević, who was the Commander-in-chief, General, Vice-Ban of Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia, was since 1602 Baron in Transylvania. It was a very difficult and complicated peace treaty after a long war.

Under Bocskay's successors Transylvania had its golden age, especially under the reigns of Gábor Bethlen and George I Rákóczi. Gábor Bethlen, who reigned from 1613 to 1629, perpetually thwarted all efforts of the emperor to oppress or circumvent his subjects, and won reputation abroad by championing the Protestant cause. Three times he waged war on the emperor, twice he was proclaimed King of Hungary, and by the Peace of Nikolsburg (31 December 1621) he obtained for the Protestants a confirmation of the Treaty of Vienna, and for himself seven additional counties in northern Hungary. Bethlen's successor, George I Rákóczi, was equally successful. His principal achievement was the Peace of Linz (16 September 1645), the last political triumph of Hungarian Protestantism, in which the emperor was forced to confirm again the articles of the Peace of Vienna. Gabriel Bethlen and George I Rákóczi also did much for education and culture, and their era has justly been called the golden era of Transylvania. They lavished money on the embellishment of their capital Alba Iulia, which became the main bulwark of Protestantism in Eastern Europe. During their reign Transylvania was also one of the few European countries where Roman Catholics, Calvinists, Lutherans, and Unitarians lived in mutual tolerance, all of them belonging to the officially accepted religions – religiones receptae, while the Orthodox, however, were only tolerated.

The fall of Nagyvárad to the expansionist Ottomans on 27 August 1660 marked the decline of the Principality of Transylvania. To counter the Ottoman threat, the Habsburg policy determined to gain influence in and perhaps control of this territory. Under Prince Kemeny, the diet of Transylvania proclaimed the secession of a sovereign Transylvania from the Ottomans (April 1661) and appealed for help to Vienna but a secret Habsburg-Ottoman agreement resulted in further increasing Habsburg influence. After the defeat of the Ottomans at the Battle of Vienna in 1683, the Habsburgs gradually began to impose their rule on the formerly autonomous Transylvania. Following the 1699 Treaty of Karlowitz, Transylvania was formally attached to the Habsburg-controlled Hungary[5][27] and subjected to the direct rule of the emperor's governors. From 1711 onward, Habsburg control over Transylvania was consolidated, and the princes of Transylvania were replaced with governors.

Demographics

Ruling system

Until 1691 Transylvania was ruled by Unio Trium Nationum, the three state-constituting socio-ethnical entities termed "nations", consisting of the Hungarian nobility, the Saxon urban settlers, and the Székely peasant-soldiers, while a significant part of the general population, consisted of Orthodox Romanians, remained deprived of any civil and political rights.[28][29]

The Composition of the Parliament

The Unio Trium Nationum (Latin for "Union of the Three Nations") was a pact of mutual aid codified in 1438 by three Estates of Transylvania: the (largely Hungarian) nobility, the Saxon (German) patrician class[30], and the free military Székelys.[31] The union was directed against the whole of the peasantry, regardless of ethnicity, in response to the Transylvanian peasant revolt.[31] In this feudal estate parliament, the peasants (whether Hungarian, Saxon, Székely or Romanian in origin) were not represented, and they did not benefit from its acts,[32] as the commoners were not considered to be members of these feudal "nations".[33]

The coalition of the "Three Nations" retained its legal representative monopoly under the prince as before the split of the medieval Hungarian Kingdom occasioned by the Ottoman invasions. According to Dennis P. Hupchick, though there were occasional clashes between the Hungarian plainsmen and the Székely mountaineers, they were united under the patronymic "Magyars" and, with Saxon support, formed a common front against the predominantly Romanian peasantry.[16]

Demographic evolution

Official censuses with information on Transylvania's population have been conducted since the 18th century, but the ethnic composition was the subject of different modern estimations.

Based on a work by Antun Vrančić (1504–1573), Expeditionis Solymani in Moldaviam et Transsylvaniam libri duo. De situ Transsylvaniae, Moldaviae et Transalpinae liber tertius, more estimations exist as the original text is translated/interpreted in a different way, especially by Romanian and Hungarian scholars. According to the Romanian interpretations, Vrančić wrote about the inhabitants of Transylvania and about the Romanians: "the country is inhabited by three nations, Székelys, Hungarians, and Saxons; I would nevertheless add the Romanians, who – even though they easily equal the others in number – have no freedom, no aristocracy, no right of their own, besides a small number living in the Haţeg district, where the capital of Decebalus is believed to have stood, and who, during the time of John Hunyadi, a native of those places, were granted aristocratic status because they had always taken part in the struggle against the Turks. The rest of them are all commoners, serfs of the Hungarians, having no places of their own, spread all over the territory, in the whole country" and "leading a wretched life",[34][35][36] while in Hungarian interpretations are noted that the proper translation of the first part of the sentence would be that "...I should also add the Romanians who – even though they easily equal any of the others in number...".[37]

According to Dennis P. Hupchick, Romanians were the majority population in the region during the rule of Stephen Báthory (16th century).[38] In 1600, according to George W. White, Romanians, who were primarily peasants, constituted more than 60 percent of the population.[39] This theory is supported by Ion Ardeleanu, who states that the Romanian population represented "the overwhelming majority" in the age of Michael the Brave.[40]

On the other hand, Károly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi argue that the Hungarians were the most numerous ethnic group before the second half of the 17th century, when they were exceeded by Romanians. They assert the following structure of the population: in 1595, out of a total population of 670,000, 52.2% were Hungarians, 28.4% Romanians, 18.8% Germans.[41] Around 1650, Moldavian prince Vasile Lupu, in a letter written to the Sultan, affirms that the number of Romanians are already more than the one-third of the population.[42] By 1660, according to Miklós Molnár, 955,000 people lived in the principality (Partium included) and the population consisted of 500,000 Hungarians (including 250,000 Székelys), 280,000 Romanians, 90,000 Germans and 85,000 Serbians, Ukrainians and others and reached its end-of-century level.[43]

In Benedek Jancsó's estimation, there were 250,000 Romanians, 150,000 Hungarians and 100,000 Saxons in Transylvania at the beginning of the 18th century.[44]

In 1720, out of a total population of 806,221, 49.6% were Romanians, 37.2% Hungarians, 12.4% Germans.[41]

Gallery

The partition of medieval Kingdom of Hungary between the Ottoman and Habsburg empires lasted more than 150 years[45] after the Battle of Mohács in 1526

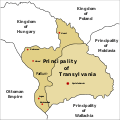

The partition of medieval Kingdom of Hungary between the Ottoman and Habsburg empires lasted more than 150 years[45] after the Battle of Mohács in 1526 The Principality of Transylvania, the successor of Eastern Hungarian Kingdom (1570). Partium is depicted in the darker colour

The Principality of Transylvania, the successor of Eastern Hungarian Kingdom (1570). Partium is depicted in the darker colour The Principality in 1606

The Principality in 1606

See also

References

- Tamásné Szabó, Csilla, Az Erdélyi Fejedelemség korának jogi nyelve (The jurisdictional language in the age of the Principality of Transylvania)

- Szabó T. Attila, Erdélyi Magyar Szótörténeti Tár (Historical dictionary of the Transylvanian Hungarian vocabulary)

- Compillatae Constitutiones Regni Transylvaniae (1671)

- Approbatae Constitutiones Regni Transylvaniae (1677)

- "Transylvania". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- Engel, Pal; Andrew Ayton (2005). The Realm of St Stephen. London: Tauris. p. 27. ISBN 1-85043-977-X.

- Helmut David Baer (2006). The struggle of Hungarian Lutherans under communism. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-1-58544-480-9. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- Eric Roman (2003). Austria-Hungary & the successor states: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present. Infobase Publishing. pp. 574–. ISBN 978-0-8160-4537-2. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- J. Atticus Ryan; Christopher A. Mullen (1998). Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization: yearbook. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-90-411-1022-0. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- Iván Boldizsár (1987). NHQ; the new Hungarian quarterly. Lapkiadó Pub. House. p. 41. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- Marshall Cavendish (2009). "Greece and the Eastern Balkans". World and Its Peoples: Europe. 11. Marshall Cavendish. p. 1476. ISBN 978-0-7614-7902-4. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- Paul Lendvai (2003). The Hungarians: a thousand years of victory in defeat. C. Hurst. pp. 106–. ISBN 978-1-85065-673-9. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- Richard C. Frucht, Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO, 2004, p. 408

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation, Viking, 2004, p. 443

- Katalin Péter, Beloved Children: History of Aristocratic Childhood in Hungary in the Early Modern Age, Central European University Press, 2001, p. 27

- Dennis P. Hupchick, Conflict and chaos in Eastern Europe, Palgrave Macmillan, 1995, p. 62

- Peter F. Sugar, Southeastern Europe under Ottoman rule, 1354–1804, University of Washington Press, 1993, pp. 150–154

- Martyn Rady, Customary Law in Hungary: Courts, Texts, and the Tripartitum, Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 141, ISBN 9780198743910

- Károly Kocsis, Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi, Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin, Simon Publications LLC, 1998, p. 106

- Transylvania article of Encyclopædia Britannica

- István Lázár, Hungary, a Brief History, 1989, ISBN 963-13-4483-5

- Peter F. Sugar, Southeastern Europe Under Ottoman Rule, 1354–1804, p. 332

- Richard Bonney; David J. B. Trim (2006). Persecution and Pluralism: Calvinists and Religious Minorities in Early Modern Europe 1550–1700. Peter Lang. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-3-03910-570-0. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- Instytut Historii (Polska Akademia Nauk), Historický ústav (Akademie věd České republiky), Political Culture in Central Europe: Middle Ages and early modern era, Institute of History, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 2005, p. 338

- István Keul, Early Modern Religious Communities in East-Central Europe: Ethnic Diversity, Denominational Plurality, and Corporative Politics in the Principality of Transylvania (1526–1691), BRILL, 2009, p. 61

- Anthony Endrey, The Holy Crown of Hungary, Hungarian Institute, 1978, p. 70

- Transylvania; The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, Columbia University Press.

- Enikö Baga (2007). Towards a Romanian Silicon Valley?: Local Development in Post-Socialist Europe. Campus Verlag. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-3-593-38126-8. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- Religiones and Nationes in Transylvania During the 16th Century: Between Acceptance and Exclusion

- Mircea Dogaru; Mihail Zahariade (1996). History of the Romanians: From the origins to the modern age, Volume 1 of History of the Romanians, History of the Romanians. Amco Press. p. 148. ISBN 9789739675598.

- László Fosztó: Ritual Revitalisation After Socialism: Community, Personhood, and Conversion among Roma in a Transylvanian Village, Halle-Wittenberg, 2007

- Ştefan Pascu (1990). A History of Transylvania. Dorset Press. p. 101. ISBN 9780880295260.

- Lucian Leuștean (2014). Orthodox Christianity and Nationalism in Nineteenth-century Southeastern Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780823256068.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel (2010). Testimonies on the ethno-confessional structure of medieval Transylvania and Hungary (9th-14th centuries) (PDF). Transylvanian Review, 2010, vol. 19, supplement No. 1, p. 9-41. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- Nations and Denominations in Transylvania (13th - 16th Century), Universita di Pisa, Dipartimento di Storia Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2012-06-01.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel (2009) - Românii și Națiunile (Nationes) Transilvănene în secolele XVI și XVII: Între excludere și acceptare

- Nyárády R. Károly - Erdély népesedéstörténete c. kéziratos munkájábol. Megjelent: A Központi Statisztikai Hivatal Népességtudományi Kutató Intézetenek történeti demográfiai füzetei. 3. sz. Budapest, 1987. 7-55. p., Erdélyi Múzeum. LIX, 1997. 1–2. füz. 1-39. p.

- Dennis P. Hupchick. Conflict and Chaos in Eastern Europe p. 64

- George W. White (2000). Nationalism and Territory: Constructing Group Identity in Southeastern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-0-8476-9809-7. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- Ion Ardeleanu; Arhivele Statului (Romania); Biblioteca Centrală de Stat a Republicii Socialiste România (1983). Mihai Viteazul în conștiința europeană: ediție de documente. Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- Károly Kocsis, Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi, Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin, Simon Publications LLC, 1998, p. 102 (Table 19)

- Sándor Szilágyi: Erdély és az északkeleti háború. Levelek és okiratok Bp. 1890 I. 246-247, 255-256 - Sándor Szilágyi: Transilvania and the north-eastern war. Letters and documents Bp. 1890 p. 246-247, 255-256

- Miklós Molnár, A Concise History of Hungary, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 113

- Demographic Changes. Mek.niif.hu. Retrieved on 2012-06-01.

- A Country Study: Hungary. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Retrieved 2009-01-11.