Treaty of London (1913)

The Treaty of London (1913) was signed on 30 May following the London Conference of 1912–13. It dealt with the territorial adjustments arising out of the conclusion of the First Balkan War.[1] The London Conference had ended on 23 January 1913, when the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état took place and Ottoman Grand Vizier Kâmil Pasha was forced to resign.[2] Coup leader Enver Pasha withdrew the Ottoman Empire from the Conference, and the Treaty of London was signed without the presence of the Ottoman delegation.[2]

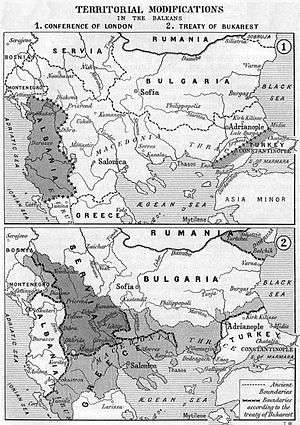

Borders of the Balkan states after the Treaty of London and the Treaty of Bucharest | |

| Signed | 30 May 1913 |

|---|---|

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Signatories | |

Combatants

The combatants were the victorious Balkan League (Serbia, Greece, Kingdom of Bulgaria, and Montenegro) and the defeated Ottoman Empire. Representing the Great Powers were Great Britain, Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Italy.[3]

History

Hostilities had officially ceased on 2 December 1912, except for Greece that had not participated in the first truce. Three principal points were in dispute:

- the status of the territory of present-day Albania, the vast majority of which had been conquered especially by Serbia, but also small regions by Montenegro, and Greece

- the status of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar formally under the protection of Austria-Hungary since the Treaty of Berlin in 1878

- the status of the other territories taken by the Allies: Kosovo; Macedonia; and Thrace

The Treaty[4] was negotiated in London at an international conference which had opened there in December 1912, following the declaration of independence by Albania on 28 November 1912.

Austria-Hungary and Italy strongly supported the creation of an independent Albania. In part, this was consistent with Austria-Hungary's previous policy of resisting Serb expansion to the Adriatic; Italy had designs on the territory, manifested in 1939. Russia supported Serbia and Montenegro. Germany and Britain remained neutral. The balance of power struck between the members of the Balkan League had been on the assumption that no Albanian polity would be formed and Albanian territory would be split between them.

Terms

The terms enforced by the Great Powers were:[4]

- All European territory of the Ottoman Empire west of the line between Enos on the Aegean Sea and Midia on the Black Sea was ceded to the Balkan League, except Albania.

- The Ottoman island of Crete was ceded to Greece, while it was left to the Great Powers to determine the fate of the other islands in the Aegean Sea.

- The borders of Albania and all other questions concerning Albania were to be settled by the Great Powers.

However, the division of the territories ceded to the Balkan League was not addressed in the Treaty, and Serbia refused to carry out the division agreed with Bulgaria in their treaty of March 1912. As a result of Bulgarian dissatisfaction with the de facto military division of Macedonia, the Second Balkan War broke out between the combatants on 16 June 1913.[5] The Bulgarians were defeated, and the Ottomans made some gains west of the Enos-Midia line. A final peace was agreed at the Treaty of Bucharest on 12 August 1913. A separate treaty, the Treaty of Constantinople, was concluded between the Bulgarians and Turks, largely defining the modern-day borders between the two countries.

Perceptions

The delineation of the exact boundaries of the Albanian state under the Protocol of Florence (17 December 1913) was highly unpopular among the local Greek population of Southern Albania (or Northern Epirus for Greeks), who, after their revolt managed to declare the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus, was internationally recognised as an autonomous region inside Albania under the terms of the Protocol of Corfu.[6]

Albanians have tended to regard the Treaty as an injustice imposed by the Great Powers, as roughly half of the predominantly Albanian territories and 40% of the population were left outside the new country's borders.[7][8]

See also

- Treaties of London

References

- Anderson, Frank Maloy; Hershey, Amos Shartle (1918). "The Treaty of London, 1913". Handbook for the Diplomatic History of Europe, Asia, and Africa 1870–1914. Washington, DC: National Board for Historical Service, Government Printing Office.

- The Treaty of London, 1913

- Richard C. Hall, ed., War in the Balkans: An Encyclopedic History from the Fall of the Ottoman Empire to the Breakup of Yugoslavia (2014) pp 172–173.

- "(HIS,P) Treaty of Peace between Greece, Bulgaria, Montenegro, Serbia on the one part and Turkey on the other part. (London) 17/30 May 1913". Zum.de. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- Richard C. Hall,The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913

- Stickney, Edith Pierpont (1926). Southern Albania or Northern Epirus in European International Affairs, 1912–1923. Stanford University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-8047-6171-0.

By the terms of the agreement of Corfu the Epirotes obtained the autonomy for which they had struggled

- Janusz Bugajski (2002). Political Parties of Eastern Europe: A Guide to Politics in the Post-Communist Era. M.E. Sharpe. p. 675. ISBN 978-1-56324-676-0. Retrieved 29 May 2012. "Roughly half of the predominantly Albanian territories and 40% of the population were left outside the new country's borders"

- Elsie, Robert (2010), "Independent Albania (1912—1944)", Historical dictionary of Albania, Lanham: Scarecrow Press, p. lix, ISBN 978-0-8108-7380-3, OCLC 454375231, retrieved 4 February 2012,

...about 30 percent of the Albanian population were excluded from the new state/about 40%... found themselves excluded from this new country p.243

Further reading

- Anderson, M.S. The Eastern Question, 1774-1923: A Study in International Relations (1966) online

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans: Twentieth Century. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521274593.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Treaty of Peace Between Turkey and the Balkan Allies, Signed at London, May 30, 1913 (Translation)". The American Journal of International Law. VIII (1, Supplement, Official Documents): 12–13. January 1914. doi:10.2307/2212402. JSTOR 2212402.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treaty of London (1913). |