Ottoman Hungary

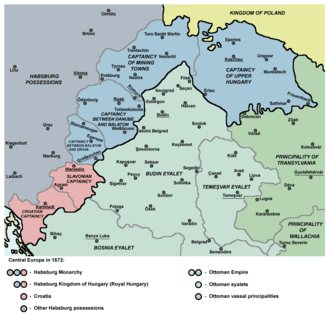

Ottoman Hungary (Hungarian: Török hódoltság) describes the history of southern and central Medieval Hungary which was conquered and ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1541 to 1699. The Ottoman rule was scattered and covered mostly the southern territories of the former medieval Kingdom of Hungary, namely almost the entire region of the Great Hungarian Plain (except the northeastern parts) and Southern Transdanubia.

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early history

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contemporary

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

History

By the sixteenth century, the power of the Ottoman Empire had increased gradually, as did the territory controlled by them in the Balkans, while the Kingdom of Hungary was weakened by the peasants' uprisings. Under the reign of Louis II Jagiellon (1516–1526), internal dissentions divided the nobility.

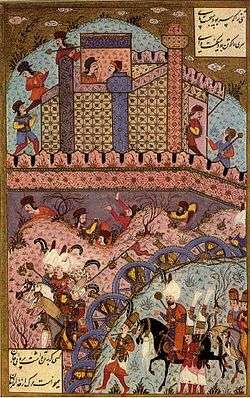

Instigating war by feigned diplomatic insult, Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566) attacked the Kingdom of Hungary and captured Belgrade in 1521. He did not hesitate to launch an attack against the weakened kingdom, whose smaller, badly led army (approximately 26,000 Hungarian soldiers compared to 45,000 Ottoman soldiers) was defeated on 29 August 1526 at the Battle of Mohács. Thus he became influential in the Kingdom of Hungary, while his semi-vassal, named John Zápolya, and his enemy Ferdinand I both claimed the throne of the Kingdom. Suleiman went further and tried to crush Austrian forces, but his Siege of Vienna in 1529 failed after the onset of winter forced his retreat. The title of king of Hungary was disputed between Zápolya and Ferdinand until 1540. After the seizure of Buda by the Ottomans in 1541,[1] the West and North recognized a Habsburg as king ("Royal Hungary"), while the central and southern counties were annexed by the Ottoman Sultan and the east was ruled by the son of Zápolya under the name Eastern Hungarian Kingdom which after 1570 became the Principality of Transylvania. Whereas a great many of the 17,000 and 19,000 Ottoman soldiers in service in the Ottoman fortresses in the territory of present-day Hungary were Orthodox and Muslim Balkan Slavs,[2] Southern Slavs were also acting as akıncıs and other light troops intended for pillaging in the territory of present-day Hungary.[3]

In these times, territory of present-day Hungary began to undergo changes due to the Ottoman occupation. Vast lands remained unpopulated and covered with woods. Flood plains became marshes. The life of the inhabitants on the Ottoman side was unsafe. Peasants fled to the woods and marshes, forming guerrilla bands, known as the Hajdú troops. Eventually, the territory of present-day Hungary became a drain on the Ottoman Empire, swallowing much of its revenue into the maintenance of a long chain of border forts. However, some parts of the economy flourished. In the huge unpopulated areas, townships bred cattle that were herded to south Germany and northern Italy - in some years they exported 500,000 head of cattle. Wine was traded to the Czech lands, Austria and Poland.[4]

The defeat of Ottoman forces led by Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha at the Second Siege of Vienna in 1683, at the hands of the combined armies of Poland and the Holy Roman Empire under John III Sobieski, was the decisive event that swung the balance of power in the region.[5] Under the terms of the Treaty of Karlowitz, which ended the Great Turkish War in 1699, the Ottomans ceded to Habsburgs much of the territory they had previously taken from the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. Following this treaty, the members of the Habsburg dynasty administered a much enlarged Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary (previously they controlled only area known as "Royal Hungary"; see Kingdom of Hungary (1526–1867)).

In the 1540s the total of the four principal fortresses of Buda (2,965), Pest (1,481), Székesfehérvár (2,978) and Esztergom (2,775) were 10,200 troops.[6]

The number of Ottoman garrison troops stationed in Ottoman Hungary vary, but during the peak period in the mid-16th century it rose to between 20,000 and 22,000 men. As a force of occupation for a country the size of Hungary, even confined to central portions it was a rather low-profile military presence in much of the country and a relatively large proportion of it was concentrated in a few key fortresses.[7]

In 1640 when the front remained relatively quiet, 8,000 Janissary supported by an undocumented number of local recruits was sufficient to garrison the whole of the Eyalet of Budin.[7]

Administration

The territory was divided into Eyalets (provinces), which were further divided into Sanjaks, with the highest ranking Ottoman official being the Pasha of Budin. At first, Ottoman-controlled territories in present-day Hungary were part of the Budin Eyalet. Later, new eyalets were formed: Temeşvar Eyalet, Zigetvar Eyalet, Kanije Eyalet, Eğri Eyalet, and Varat Eyalet. Administrative centers of Budin, Zigetvar, Kanije and Egir eyalets were located in the territory of present-day Hungary, while Temeşvar and Varat eyalets that had their administrative centers in the territory of present-day Romania also included some parts of present-day Hungary. Pashas and Sanjak-Beys were responsible for administration, jurisdiction and defense. The Ottomans' only interest was to secure their hold on the territory.

The Sublime Porte (Ottoman rulers) became the sole landowner and managed about 20 percent of the land for its own benefit, apportioning the rest among soldiers and civil servants. The Ottoman landlords were interested mainly in squeezing as much wealth from the land as quickly as possible. Of major importance to the Sublime Porte was the collection of taxes. Taxation left little for the former landlords to collect; Most of the nobility and large numbers of burghers emigrated into the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary ("Royal Hungary") province. Wars, slave-taking, and the emigration of nobles who lost their land caused a depopulation of the countryside. However, the Ottomans practiced relative religious tolerance and allowed the various ethnicities living within the empire significant autonomy in internal affairs. Towns maintained some self-government, and a prosperous middle class developed through artisanry and trade.

At least one ethnic Hungarian became Grand Vizier, the highest governmental office in the Ottoman Empire: Hadım Süleyman Pasha.

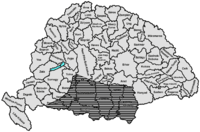

Ethnic changes during the Ottoman rule

As a consequence of the 150 years of constant warfare between the Christian states and Ottomans, population growth was stunted, and the network of ethnic Hungarian medieval settlements, with their urbanized bourgeois inhabitants, perished. The ethnic composition of the territory that had been part of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary was fundamentally changed through deportations and massacres, so that the number of ethnic Hungarians in existence at the end of the Ottoman period was substantially diminished.[8]

The economic decline of Buda the capital city during the Ottoman conquest characterized by the stagnation of population. The population of Buda was not larger in 1686 than two centuries earlier in the 15th century.[9] The Ottomans allowed the Hungarian royal palace to fall into ruins.[10] The Ottomans later transformed the palace into a gunpowder store and magazine,[11] which caused its detonation during the siege in 1686. The Christian Hungarian population significantly shrank in the next decades, due to them fleeing to the Habsburg-ruled Royal Hungary. The number of Jewish and Gypsy immigrants became dominant during the Ottoman rule in Buda.[12]

The Hungarian inhabitants of cities moved to other places when they felt threatened by the Ottoman military presence. Without exception, in the cities that became Ottoman administrative centers the Christian population decreased. The Hungarian population remained only in some cities, where the Ottoman garrisons were not installed.[13] From the early 17th century, Serbian refugees were the ethnic majority in large parts of Ottoman-controlled Hungary. That area included territories between the great rivers Sava, Drava, and the Danube–Tisza Interfluve (the territory between the Danube and Tisza rivers).[14]

According to modern estimations, the proportion of Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin was around 80% at the end of the 15th century, and non-Hungarians hardly were more than 20% to 25% of the total population.[15][16][17][18] The Hungarian population began to decrease at the time of the Ottoman conquest,[15][16] The decline of the Hungarians was due to the constant wars, Ottoman raids, famines, and plagues during the 150 years of Ottoman rule.[15][16][19] The main zones of war were the territories inhabited by the Hungarians, so the death toll depleted them much faster than other nationalities.[15][19]

The three parts of Hungary; the Habsburg Hungary, Ottoman Hungary and Transylvania, experienced only minor differences in population increase in the 17th century.[20] According to data presented in the most authoritative studies, the collective population of all three regions grew from about 3.5 million inhabitants at the close of the 16th century to about 4 million by the close of the 17th century.[20] This increase was before the immigration to Hungary from other parts of the Habsburg Empire.[21] The Ottoman–Habsburg wars of the 17th century were fought intermittently and affected populations occupying a much narrower band of territory.[20] Thus wartime dislocations in Hungary do not seem to have seriously affected mortality rates among the general civilian population.[20] The breakdown of social order and other economic links between contiguous regions that is associated with prolonged warfare of the medieval pattern was largely absent in Ottoman warfare of the 17th century.[20] The most severe destructions were experienced during the Hungarian time of troubles, when between 1604 and 1606 the worst effects of the controlled confrontation between Ottoman-Habsburg forces were magnified many times over by Hungary's descent into civil war during the Bocskay rebellion.[20]

Hungary's population in the late 16th century was in Ottoman Hungary 900,000, in Habsburg Hungary 1,800,000 and 'free' (Transylvania) Hungary 800,000, making a total of 3,500,000 inhabitants for the whole of Hungary.[21]

The population growth in Ottoman Hungary during the 17th century was slight: from 900,000 to approximately 1,000,000 inhabitants, a rate similar to that experienced in Royal Hungary and Transylvania.[21]

Culture

Despite the continuous warfare with the Habsburgs, several cultural centres sprang up in this far northern corner of the Empire. Examples of Ottoman architecture of the classical period, seen in the famous centres of Constantinople and Edirne, were also seen in the territory of present-day southern Hungary, where mosques, bridges, fountains, baths and schools were built. After the Habsburg reclamation, most of these works were destroyed and few survive to this day. The introduction of Turkish baths, with the building of the Rudas Baths, was the beginning of a long tradition in the territory of present-day Hungary. No less than 75 hammams (steam baths) were built during the Ottoman age.

Muslim schools

In the seventeenth century, 165 elementary (mekteb) and 77 secondary and academic theological schools (medrese) were operating in 39 of the major towns of the region. The elementary schools taught writing, basic arithmetics, and the reading of the Koran and of the most important prayers. The medreses carried out secondary and academic training within the fields of Muslim religious sciences, church law and natural sciences. Most medreses operated in Budin (Buda), where there were twelve. In Peçuy (Pécs) there were five medreses, Eğri had four. The most famous medrese in Ottoman-controlled territory of present-day Hungary was that of Budin (Buda), built by the Serb Mehmed-pasha Sokolović during his seventeen years of governing (1566–1578).

In the mosques, people not only prayed, but were taught to read and write, to read the Koran, and prayers. The sermons were the most effective form of political education. There were numerous elementary and secondary schools besides the mosques, and the monasteries of the Dervish orders also served as centers of culture and education. The spread of culture was supported by the libraries. The school library of Mehmed-pasha Sokolović in Budin (Buda), contained, besides Muslim religious sciences, other literature, works on oratory, poetry, astronomy, music, architecture, and medical sciences.

Religion

The Ottomans practiced relative religious tolerance, and Christianity was not prohibited. Islam was not spread by force in the areas under the control of the Ottoman Sultan,[22] however, Arnold biasedly concludes by quoting a 17th-century author who stated:

Meanwhile he [the Turk] wins [converts] by craft more than by force, and snatches away Christ by fraud out of the hearts of men. For the Turk, it is true, at the present time compels no country by violence to apostatise; but he uses other means whereby imperceptibly he roots out Christianity...[23]

The relative religious tolerance of the Ottomans enabled Protestantism in Hungary (such as the Reformed Church in Hungary) to survive against the oppression of the Catholic Habsburg-ruled Hungarian domains.

There were approximately 80,000 Muslim settlers in Ottoman-controlled territory of present-day Hungary; being mainly administrators, soldiers, artisans and merchants of Crimean Tatar origin. The religious life of the Muslims was supervised by the mosques that were either newly built or transformed from older Christian churches. Payment for the servants of the mosques, as well as the maintenance of the churches, was the responsibility of the Ottoman state or charities.

Besides Sunni Islam, a number of dervish communities also flourished including the bektashis, the halvetis, and the mevlevis. The famous Gül Baba monastery of Budin (Buda), sheltering 60 dervishes, belonged to the bektasi order. Situated close to the janissaries camp, it was built by Jahjapasazáde Mehmed Pasha, the third begler bey (governor) of Budin. Gul Baba's tomb (türbe) is to this day the northernmost site of Islamic conquest.[24]

Another famous monastery of its time was that of the halveti dervishes. Built around 1576 next to the türbe of Sultan Süleyman I the Magnificent (1520–1566) in Sigetvar (Szigetvár), it soon became the religious and cultural centre of the area. A famous prior of the zavije (monastery) was the Bosnian Šejh Ali Dede. The monastery of Jakovali Hasan Paša in Peçuy (Pécs) was another famous location. Its most outstanding prior was Mevlevian dervish Peçevi Arifi Ahmed Dede, a Turk and native of Peçuy.

By the end of the sixteenth century, around 90% of the inhabitants of Ottoman Hungary were Protestant, most of them being Calvinist.[25]

Gallery

The Pasha of Budin (Buda) receives the envoy of the Ottoman Sultan.

The Pasha of Budin (Buda) receives the envoy of the Ottoman Sultan. Coffee shop

Coffee shop Köçek dancer with castanets. Ottoman miniature by Balázs Szigetvári Csöbör, 1570.

Köçek dancer with castanets. Ottoman miniature by Balázs Szigetvári Csöbör, 1570. Slave woman musician

Slave woman musician

See also

- Islam in Hungary

- Transformation of the Ottoman Empire#Hungary - on the Ottoman defensive system in Hungary.

- Magyarabs

- Ottoman–Habsburg wars

References

- Melvin E. Page, Colonialism: an international social, cultural, and political encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2003, p. 648

- Kontler 1999, p. 145.

- Inalcik Halil: "The Ottoman Empire"

- http://www.hungarianhistory.com/lib/hunspir/hsp25.htm

- "Part I - The Decline of the Ottoman Empire - MuslimMatters.org". muslimmatters.org.

- Ottoman Warfare 1500-1700, Rhoads Murphey, 1999, p.227

- Ottoman Warfare 1500–1700, Rhoads Murphey, 1999, p.56

- Csepeli, Gyorgy (1996). "The changing facets of Hungarian nationalism - Nationalism Reexamined". Social Research. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- András Gerő, János Poór (1997). Budapest: a history from its beginnings to 1998, Volume 86 van Atlantic studies on society in change , Volume 462 van East European monographs. Social Science Monographs. p. 3. ISBN 9780880333597.

- Andrew Wheatcroft (2010). The Enemy at the Gate: Habsburgs, Ottomans, and the Battle for Europe. Basic Books. p. 206. ISBN 9780465020812.

- Steve Fallon, Sally Schafer (2015). Lonely Planet Budapest. Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781743605059.

- Ga ́bor A ́goston, Bruce Alan Masters (2009). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire Facts on File Library of World History Gale virtual reference library. Infobase Publishing. p. 96. ISBN 9781438110257.

- IM Kunt and Christine Woodhead (2014). Suleyman the Magnificent and His Age: The Ottoman Empire in the Early Modern World. Routledge. pp. 87–88. ISBN 9781317900597.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Carl Skutsch (2013). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. New York City: Routledge. p. 1082. ISBN 9781135193881.

- Hungary. (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 May 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- A Country Study: Hungary. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- "International Boundary Study – No. 47 – April 15, 1965 – Hungary – Romania (Rumania) Boundary" (PDF). US Bureau of Intelligence and Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2009.

- Historical World Atlas. With the commendation of the Royal Geographical Society. Carthographia, Budapest, Hungary, 2005. ISBN 978-963-352-002-4 CM

- Steven W. Sowards. "Twenty-Five Lectures on Modern Balkan History (The Balkans in the Age of Nationalism), Lecture 4: Hungary and the limits of Habsburg authority". Michigan State University Libraries. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- Ottoman Warfare 1500–1700, Rhoads Murphey, 1999, p.173-174

- Ottoman Warfare 1500–1700, Rhoads Murphey, 1999, p.254

- The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg. 135-144

- The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg. 136

- Christina Shea, Joseph S. Lieber, Erzsébet Barát, Frommer's Budapest & the Best of Hungary, John Wiley and Sons, 2004, p 122-123

- Patai, Raphael (1996). The Jews of Hungary: History, Culture, Psychology. Wayne State University Press. p. 153. ISBN 0814325610.

- Encyclopaedia Humana Hungarica: Cross and Crescent: The Turkish Age in Hungary (1526–1699)

- Balázs Sudár: Baths in Ottoman Hungary in "Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae", Volume 57, Number 4, 7 December 2004, pp. 391–437(47)

Sources

- Kontler, László (1999). Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fodor, Pál; Dávid, Géza, eds. (2000). Ottomans, Hungarians, and Habsburgs in Central Europe: The Military Confines in the Era of Ottoman Conquest. BRILL.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)