Timeline of the Song dynasty

10th century

960s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 960 | February | Zhao Kuangyin declares himself Emperor Taizu of Song, replacing Later Zhou[1] |

| 963 | Song conquers Jingnan[1] | |

| Song dynasty introduces the appointment by protection system, which allows high officials to nominate their sons, grandsons, and nephews for the civil service[2] | ||

| 965 | Song conquest of Later Shu: Song conquers Later Shu[1] | |

| Tao Gu provides the first written documentation of using cormorants for fishing[3] | ||

| 967 | Long Yanyao of Nanning, the Yang clan of Bo Prefecture, and the Tian clan of Si Prefecture submit to the Song dynasty in return for their autonomy[4] | |

| Song dynasty recognizes the Bole of the Luodian kingdom, the Mangbu of the Badedian kingdom, and the Awangren of the Yushi kingdom[5] | ||

| 968 | Đinh Bộ Lĩnh of the Đinh dynasty declares independence from China[6] | |

| 969 | Gunpowder propelled fire arrows, rocket arrows, are invented by Yue Yifang and Feng Jisheng.[7] |

970s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 971 | Song conquest of Southern Han: Song conquers Southern Han - marks the last time elephants are used in Chinese warfare[1] | |

| 974 | The earliest natural history of pharmaceuticals, the Kaibao Bencao, is printed[8] | |

| 975 | Song conquest of Southern Tang: Song conquers Southern Tang[1] | |

| Emperor Taizu of Song tries to convince Pugui of the Mu'ege Kingdom situated in northwest, central, east, and southeast Guizhou to acquiesce to Song overlordship[9] | ||

| 976 | 14 November | Emperor Taizu of Song dies and his brother Zhao Guangyi succeeds him as Emperor Taizong of Song[10][11] |

| Song dynasty and aboriginal allies in Guizhou attack the Mu'ege Kingdom, forcing them to retreat to Dafang County[12] | ||

| 977 | The price ratio of iron to rice reaches 632:100[13] | |

| 978 | Song conquers Wuyue[1] | |

| 979 | Song conquest of Northern Han: Song conquers Northern Han[1] | |

| Battle of Gaoliang River: Song dynasty invades Liao dynasty and is defeated[14] |

980s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 980 | Emperor Jingzong of Liao invades the Song dynasty and retakes territory in Hebei[14] | |

| Long Yanyao's grandson Long Qiongju presents tribute to the Emperor Taizong of Song[4] | ||

| 981 | Battle of Bạch Đằng (981): Song dynasty invades Early Lê dynasty with initial success but is ambushed and the campaign ends with Lê Hoàn accepting Song suzerainty[15] | |

| 982 | Li Jipeng of the Dingnan Jiedushi surrenders to the Song, but his cousin Li Jiqian rebels[16] | |

| 983 | The complete 130,000 block print edition of the Tripiṭaka Buddhist Canon (Kaibao zangshu 開寶藏書) is finished[17] | |

| 984 | Qiao Weiyue invents the pound lock[18] | |

| 986 | Song dynasty attacks the Khitans but is defeated[19] |

990s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 993 | A drought hits Sichuan and peasant rebellions break out[20] | |

| 994 | Song dynasty deposes Li Jiqian[16] | |

| Earliest record of promissory note[21] | ||

| 995 | Rebellions in Sichuan are suppressed[22] | |

| Long Hanyao of Nanning presents tribute to the Song court[4] | ||

| 996 | Li Jiqian rebels with Tanguts and raids Song supplies[16] | |

| 997 | 9 May | Emperor Taizong of Song dies and his son Zhao Heng becomes Emperor Zhenzong of Song[23] |

| 998 | Khitans invade the Song dynasty[24] | |

| Song dynasty legitimizes Li Jiqian as governor of Dingnan Jiedushi[16] | ||

| Long Hanyao of Nanning presents tribute to the Song court[4] |

11th century

1000s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1000 | Khitan forces retreat from the Song dynasty after failing to take key cities[24] | |

| Tang Fu demonstrates gunpowder pots and caltrops to the Song court and is rewarded.[25] | ||

| Chinese discover that magnetic north and true north are not the same[26] | ||

| 1001 | Tanguts capture Ordos[27] | |

| Khitans attack the Song dynasty but are repulsed[24] | ||

| 1002 | Shi Pu demonstrates fireballs utilizing gunpowder to the Song court and blueprints are created for promulgation throughout the realm.[25] | |

| 1003 | Khitans invade the Song dynasty and retreat without making permanent gains[24] | |

| 1004 | Emperor Shengzong of Liao conducts a full-scale invasion of the Song dynasty which ends in stalemate[28] | |

| 1005 | January | Chanyuan Treaty: The Song dynasty agrees to pay the Khitans an annual tribute of silk and silver[29] |

| 1009 | Emperor Zhenzong of Song introduces quotas on degrees awarded[30] | |

| Song dynasty modifies the appointment by protection system by requiring candidates to study at the Directorate of Education and sit the examination, which passes at least 50 percent of them[2] |

1010s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1010 | Tanguts request famine relief from the Song[31] | |

| 1012 | Song court sponsors the propagation of the early maturing Champa rice, allowing rice to be harvested twice a year[32] | |

| 1016 | Locusts plague the Song capital of Kaifeng[31] | |

| 1018 | Yellow River dikes collapse[33] |

1020s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1021 | Agricultural land reaches 13 percent of Song state territory[34] | |

| 1022 | 23 March | Emperor Zhenzong of Song dies and his son succeeds him as Emperor Renzong of Song; Empress Liu becomes regent[35] |

| 1023 | Song dynasty establishes a Bureau for Exchange Bills in Chengdu after craftsmen, artisans, and farmers reject the replacement of the smaller copper coins with heavy iron coins[21] | |

| Song dynasty starts circulating exchange bills, each worth 1,256,340 strings of cash per 3-year circulation period[36] | ||

| 1024 | Earliest known extant printing block for paper money, the jiaozi[37] | |

| 1026 | Torrential rains damage the Yellow River dikes and cause widespread flooding in the Song capital of Kaifeng[33] | |

| 1027 | Repairs on the Yellow River dikes are finished[33] |

1030s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1033 | Empress Liu's regency ends as she dies[35] | |

| Drought hits northern China[38] | ||

| 1034 | Li Yuanhao of the Tanguts raids Song dynasty[39] | |

| 1036 | Unprecedented spread of literati culture throughout society compels the Song court to promulgate sumptuary regulations for citizens of Kaifeng[40] | |

| Song civil service doubles in size[40] | ||

| All officials, their sons and grandsons, are relieved from obligations to serve as village officers[40] | ||

| 1037 | Earthquake kills 12,000 people, injures 5,600, and kills or injures 50,000 cattle around Kaifeng[41] | |

| 1038 | 10 November | Li Yuanhao declares himself Emperor Jingzong of Western Xia[39] |

| Rebellion breaks out in Guangnan West Circuit and is suppressed[42] | ||

| 1039 | Western Xia attacks Song dynasty but is repulsed[43] | |

| Famine strikes north China[44] |

1040s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1040 | Western Xia invades Song dynasty[44] | |

| 1041 | Western Xia defeats a Song army and kills 6,000[45] | |

| Movable type is invented by Bi Sheng[46] | ||

| 1042 | Western Xia conducts a full-scale invasion of the Song dynasty but is repelled[47] | |

| Khitans force the Song dynasty to increase annual tribute to 200,000 taels of silver and 300,000 bolts of silk[48] | ||

| Song dynasty appoints Degai of the Mu'ege Kingdom as regional inspector[12] | ||

| 1043 | The Yao people of Guiyang rebel[42] | |

| Emperor Renzong of Song enacts the Confucian Qingli Reforms and schools are established at prefectures with sufficient number of students[49] | ||

| The School of Four Gates opens - it provides students with a 500-day education, stipends, meals, a place in the dormitory, and exemption from the prefectural examinations[50] | ||

| 1044 | Western Xia and Song dynasty cease hostilities[51] | |

| Rebellion breaks out in Guangnan West Circuit and is suppressed[42] | ||

| Rebellions break out in Sichuan[42] | ||

| The chemical formula for gunpowder appears in the military manual Wujing Zongyao, also known as the Complete Essentials for the Military Classics.[52][53] | ||

| "Thunderclap bombs" are mentioned in the Wujing Zongyao.[54] | ||

| A "triple-bed-crossbow" firing fire arrows is mentioned in the Wujing Zongyao.[55] | ||

| Earliest recorded use of the compass for navigation[56] | ||

| 1046 | Proportion of jinshi degree holders in the Song dynasty bureaucracy reach a third of all total bureaucratic positions[57] | |

| 1047 | Drought hits northern China[58] | |

| 1048 | Wang Ze rebels in Hebei and is suppressed[58] | |

| 1049 | Nong Zhigao of the Zhuang people rebels in Guangnan West Circuit[42] | |

| Rebellions in Sichuan are suppressed[42] | ||

| The Iron Pagoda is completed[59] |

1050s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1051 | The Yao rebellion of Guiyang is suppressed[42] | |

| 1053 | Nong Zhigao's rebellion is suppressed[42] | |

| 1055 | Peng Shixi rebels in Jinghu[42] | |

| 1056 | Heavy rains overload the Yellow River, causing widespread flooding and a major shift in the river's course[58] | |

| 1058 | Rebellion breaks out in Yongzhou[42] | |

| Peng Shixi's rebellion is suppressed[42] | ||

| 1059 | The Luoyang Bridge (Quanzhou) is completed[60] |

1060s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1061 | The rebellion in Yongzhou is suppressed[42] | |

| 1063 | 30 April | Emperor Renzong of Song dies and his cousin Zhao Zongshi succeeds him as Emperor Yingzong of Song[61] |

| 1064 | Western Xia raids Song dynasty[62] | |

| 1065 | fall | Kaifeng experiences massive floods[63] |

| 1066 | Western Xia raids Song dynasty[64] | |

| The Song court starts holding jinshi examinations triennially, a decision that would endure until 1905[65] | ||

| 1067 | 25 January | Emperor Yingzong of Song dies and his son Zhao Xu succeeds him as Emperor Shenzong of Song[66] |

| Private trade of gunpowder ingredients is banned in the Song dynasty.[67] | ||

| 1068 | Enrollment in the School of Four Gates reaches 900[50] | |

| Huang Huaixin starts planning the construction of dry docks[68] |

1070s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1070 | Western Xia attacks the Song dynasty[69] | |

| The Song court carries out water-control and land reclamation projects which reclaim 38,829,799 acres of agricultural land[70] | ||

| Annual copper production in the Song dynasty reaches 12,982 tons, more than the total global production in 1800[71] | ||

| The first jinshi imperial examinations to emphasize statecraft over poetry are held[72] | ||

| 1072 | Song dynasty starts colonizing the Qinghai region[73] | |

| 1075 | Lý–Song War: Lý Thường Kiệt and Nùng Tông Đán of the Lý dynasty invade the Song dynasty, capturing Qinzhou, Lianzhou, and destroying Yongzhou before retreating[73][74] | |

| Shen Kuo describes the process of making steel using repeated forging under a cold blast for "partial decarbonization", considered by some historians to be a direct predecessor of the Bessemer process[75] | ||

| 1076 | autumn | Lý–Song War: Guo Kui of the Song dynasty invades the Lý dynasty and pushes to the Cầu River, where the war reaches a stalemate[76] |

| Trade of gunpowder ingredients with the Liao and Western Xia dynasties is outlawed by the Song court[25] | ||

| 1077 | Lý–Song War: Lý dynasty becomes a Song tributary in return for the withdraw of Song troops[73][77] | |

| 1078 | Annual iron production in the Song dynasty reaches 125,000 tons and becomes the largest iron industry in the world, an achievement that lasts until 1796 during the industrial revolution in England and Wales;[78][79] per capita iron production reaches 3.1 pound, the world's highest per capita iron production until 1700 in Western Europe[79] | |

| 1079 | Lý–Song War: Song dynasty gives up claims to Cao Bằng and Lạng Sơn in return for Song captives[77] |

1080s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1080 | Number of qualified officials reach 34,000[80] | |

| Mints in the Song dynasty reach annual production of 5,000,000 strings of copper cash and 800,000 strings of iron coins[81] | ||

| The Price ratio of iron to rice falls to 177:100 in Sichuan and 135:100 in Shanxi[13] | ||

| 1081 | Song dynasty invades Western Xia with initial success, but the odd failure to bring siege weapons and extreme supply problems cause widespread mutiny and the invasion turns into a massive rout[82] | |

| 1083 | Three hundred thousand fire arrows are produced by the Song court and delivered to two garrisons.[25] | |

| 1085 | 1 April | Emperor Shenzong of Song dies and his son Zhao Xu succeeds him as Emperor Zhezong of Song; Empress Gao becomes regent[83] |

| Drought hits the Kaifeng region[84] | ||

| Annual grain harvest reaches 18,700,000 tons[85] | ||

| 1086 | Su Song invents the astronomical clock[86] | |

| 1088 | Song and Lý finalize their border agreement, which with minor changes throughout the centuries, is basically the same as the modern China–Vietnam border[87] | |

| 1089 | Song and Western Xia conclude a peace treaty[88] |

1090s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1092 | Earliest known extant depiction of an endless power-transmitting chain drive[89] | |

| 1093 | Emperess Gao's regency ends as she dies[90] | |

| 1097 | Song dynasty conducts an advance and fortify campaign against the Western Xia[91] | |

| 1098 | Western Xia retaliates against Song incursions but fails to defeat Song fortifications[92] | |

| 1099 | Western Xia sues for peace[92] |

12th century

1100s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1100 | 23 February | Emperor Zhezong of Song dies and his brother Zhao Ji succeeds him as Emperor Huizong of Song[93] |

| Total population employed in the Song bureaucracy reaches 0.02 percent[94] | ||

| Coke (fuel) replaces charcoal in iron smelting[95] | ||

| 1102 | The Song court mandates the construction of Security and Relief clinics in every prefecture[96] | |

| Cai Jing suggests that the best graduates of the Taixue should be selected for appointment without having to take the imperial examinations and that the examinations themselves should be replaced by a reformed education system; his ideas are ultimately rejected[50] | ||

| 1103 | Song dynasty invades Western Xia[97] | |

| Public pharmacies are extended from Kaifeng to the circuits[96] | ||

| Earliest recorded references to foot binding[98][99][100] | ||

| 1104 | Song annexes Tsongkha[101] | |

| Song court mandates public cemeteries for the destitute[102] | ||

| The Taixue allows enrollment from poor families for an admission fee of 2,000 cash, roughly 4 months of income for a low wage farmer, or 15 percent of monthly salary for a low official[103] | ||

| 1105 | Reports of embezzlement relating to the public welfare initiatives start rolling in[104] | |

| 1106 | Song dynasty and Western Xia end hostilities and the war ends inconclusively[97] | |

| Graduates of the prefectural examinations are reduced to 3% of candidates[30] | ||

| 1107 | Song dynasty starts issuing a new note called a 'money voucher' (qianyin)[105] | |

| Song dynasty mandates the superiority of the Taoist clergy in rank and honors to their Buddhist counterparts[106] | ||

| 1108 | Song dynasty sets an annual recruitment quota of 70 Taoist priests for the imperial examinations[106] |

1110s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1110 | The Song army puts on a firework display for the emperor including a spectacle which opened with "a noise like thunder" and explosives that light up the night. Considered by some to be the first mention of gunpowder fireworks.[107] | |

| 1111 | Earliest recorded use of the compass for maritime navigation[108] | |

| 1113 | Song dynasty invades Western Xia[97] | |

| 1114 | The Palace of Extended Blessings (Yanfu Gong), a park-like compound extending the palace precincts to the north, is constructed[109] | |

| 1115 | 28 January | Wanyan Aguda declares himself Emperor Taizu of Jin[110] |

| 1119 | The war between Song dynasty and Western Xia ends inconclusively[97] | |

| Song Jiang rebels in Jingdong Circuit[111] |

1120s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1120 | Fang La rebels in Liangzhe Circuit and is suppressed[112] | |

| Song court announces cutbacks to public welfare[102] | ||

| 1121 | Song Jiang's rebellion in Jingdong Circuit is suppressed[113] | |

| 1123 | Song dynasty attacks the Liao dynasty but is repelled[114] | |

| Zhang Jue rebels in Ping Prefecture and defects to the Song dynasty but the Jin dynasty immediately retaliates and crushes his army; Zhang Jue is executed by the Song as reconciliation towards the Jin[115] | ||

| 1125 | 26 March | Emperor Tianzuo of Liao is captured by the Jin dynasty; so ends the Liao dynasty[116] |

| November | Jin dynasty invades the Song dynasty and occupies Shanxi and Hebei[115] | |

| 1126 | 18 January | Emperor Huizong of Song abdicates to his son Zhao Huan, who succeeds him as Emperor Qinzong of Song[117] |

| 31 January | Jingkang Incident: Thunderclap bomb as well as fire arrows and fire bombs are used by Song troops during the siege of Kaifeng by the Jin dynasty (1115–1234).[118] | |

| 5 March | Jin army retreats from Kaifeng after the Song dynasty promises to pay an annual indemnity[119] | |

| June | Jin dynasty defeats two Song armies[119] | |

| December | Jin army returns with fire arrows and gunpowder bombs and lays siege to Kaifeng[119][120] | |

| 1127 | 12 June | Emperor Qinzong of Song's brother Zhao Gou is declared Emperor Gaozong of Song and the capital is moved to Lin'an[121] |

| December | Jingkang Incident: Kaifeng falls to the Jin dynasty and emperors Qinzong and Huizong are captured; territory north of the Huai River is annexed by the Jin[122] - earliest recorded use of "molten metal bombs", suspected to contain gunpowder[120] | |

| 1128 | The earliest extant depiction of a cannon appears among the Dazu Rock Carvings, one of which is a human figure holding a gourd shaped hand cannon.[123] | |

| 1129 | Former Song official Liu Yu is enthroned as emperor of the Jin puppet state of Qi[124] | |

| Gunpowder weapons are applied to naval warfare as Song warships are outfitted with trebuchets and supplies of gunpowder bombs.[125] |

1130s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1130 | Battle of Huangtiandang: Jin forces are ambushed and stopped at the Yangtze for some time before making the crossing[126] | |

| Zhong Xiang rebels in Hunan[127] | ||

| 1131 | Jin dynasty invades Shaanxi but is repelled, in particular by a volley fire tactic implemented by general Wu Jie (吳 玠) and his younger brother Wu Lin (吳璘)[128] | |

| Li Cheng rebels in Huainan and is suppressed[129] | ||

| The Song dynasty establishes China's first standing navy[130] | ||

| 1132 | Siege of De'an: Fire lances are used by Song troops to repel Jin invaders[131][132][133] | |

| Gunpowder is referred to specifically for its military applications for the first time and is known as "fire bomb medicine" rather than "fire medicine".[125] | ||

| Firecrackers using gunpowder are mentioned for the first time.[134] | ||

| 1133 | Jin puppet state Qi invades Song dynasty but is repelled by Yue Fei[135] | |

| Ayong of the Mu'ege Kingdom leads a large trade delegation of several thousand to the Song city of Luzhou in Sichuan[5] | ||

| 1135 | 4 June | Emperor Huizong of Song dies[121] |

| Jin puppet state Qi captures Xiangyang[136] | ||

| Yue Fei of the Song dynasty retaliates and recaptures much of the lost territory[136] | ||

| The rebellion in Hunan is suppressed[127] | ||

| 1136 | Jin puppet state Qi invades the Song dynasty but is repelled[137] |

1140s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1140 | Jin dynasty invades Song dynasty[138] | |

| Battle of Yancheng: Yue Fei launches a successful attack against the Jin and makes considerable territorial gains, but is forced to withdraw by Emperor Gaozong of Song[139] | ||

| 1141 | Yue Fei is arrested[140] | |

| 1142 | 27 January | Yue Fei is executed[141] |

| October | Song and Jin agree to the Treaty of Shaoxing which stipulates that the Song must pay Jin an annual indemnity; the Huai River is settled as the boundary between the two states[142][139] | |

| 1143 | Buddhist monks in the Song dynasty surge to 200,000 and become the largest class of land owners[143] | |

| 1145 | The Dongguan Bridge is constructed in Yongchun County, Fujian Province[144] |

1150s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1150 | Annual registration for prefectural examinations reaches 100,000 applicants[30] | |

| 1151 | The Anping Bridge is completed[145] |

1160s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1160 | Song dynasty starts issuing huizi, their official paper currency[146] | |

| 1161 | 14 June | Emperor Qinzong of Song dies[121] |

| 28 October | Jin dynasty invades Song dynasty[147] | |

| 16 November | Battle of Tangdao: Fire arrows are employed by a Song fleet in sinking a Jin fleet off the shore of Shandong peninsula.[148] | |

| 26–27 November | Battle of Caishi: Thunderclap bombs are employed by Song treadmill boats in sinking a Jin fleet on the Yangtze.[148] | |

| 1162 | 24 July | Emperor Gaozong of Song abdicates to his adopted son Zhao Bocong who becomes Emperor Xiaozong of Song[149] |

| Copper production in the Song dynasty suffers a complete breakdown and falls to 157 tons per year[71] | ||

| 1163 | summer | Song dynasty invades Jin dynasty but is defeated[150] |

| Fire lances are attached to war carts, known as "at-your-desire-war-carts", for defending Song mobile trebuchets.[125] | ||

| 1165 | Song and Jin conclude a peace treaty reducing Song tribute and returning borders to the Huai River[151] | |

| 1167 | Song dynasty releases 2 million taels to exchange for huizi and destroy them in order to correct overissue[146] |

1170s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1170 | The Song dynasty stations officers at the Penghu Islands[152] | |

| 1171 | Chinese fishermen settle on the Penghu Islands[153] | |

| 1175 | More huizi are issued to meet demand[146] |

1180s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1181 | Earliest extant printed maps with a date of publication are printed[154] | |

| 1187 | 9 November | Emperor Gaozong of Song dies[155] |

| 1188 | Emperor Xiaozong of Song creates a new office called the Policy Deliberation Hall (Yishi tang) to train his son Zhao Dun for his eventual accession[156] | |

| 1189 | 18 February | Emperor Xiaozong of Song abdicates to his son Zhao Dun, who becomes Emperor Guangzong of Song[157] |

1190s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1190 | Casual references to foot binding become more common; foot binding is no longer associated with dancing nor is the practice confined to entertainers[100] | |

| 1191 | Emperor Guangzong of Song withdraws from the court[158] | |

| 1194 | 28 June | Emperor Xiaozong of Song dies[159] |

| 24 July | Emperor Guangzong of Song is forced to abdicate and his son Zhao Kuo succeeds him as Emperor Ningzong of Song[160] | |

| 1195 | Rebellion breaks out in Sichuan[161] | |

| Earliest known extant depiction of a fishing reel[162] | ||

| 1198 | Song court bans Neo-Confucianism[163] |

13th century

1200s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1200 | 17 September | Emperor Guangzong of Song dies[164] |

| 1202 | Ban on Neo-Confucianism ends[165] | |

| 1204 | Song forces start showing military aggression along the Jin border[166] | |

| 1206 | spring | Kokochu, also known as Teb Tengri, chief shaman of the Mongols, bestows upon Temüjin the title of Genghis Khan, "Oceanic Ruler" of the Mongol Empire, at the kurultai of Burkhan Khaldun, sacred mountain of the Mongols[167] |

| 20 June | Song dynasty declares war on Jin dynasty[166] | |

| December | The governor-general of Sichuan, Wu Xi, defects to the Jin dynasty[168] | |

| 1207 | 29 March | Song loyalists kill Wu Xi[168] |

| Thunderclap bombs are employed by Song forces in a sneak attack on a Jin camp, killing 2000 men and 800 horses.[54] | ||

| April | Song and Jin enter a stalemate[168] | |

| 1208 | 2 November | Song and Jin agree to a peace renewing the Song's tributary relationship with the Jin[169] |

| Yao people rebel in Jinghu and are suppressed[170] | ||

| Rebellion breaks out in Sichuan[161] | ||

| Massive fires erupt in Lin'an[171] | ||

| Drought and locusts hits Zhejiang[171] | ||

| 1209 | Locusts plague Zhejiang[171] |

1210s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1210 | Rebellion breaks out in Jinghu and is suppressed[170] | |

| Earliest known depiction of a trip hammer[172] | ||

| Floodwaters and locusts hit Zhejiang[171] | ||

| 1211 | Massive fires erupt in Lin'an[171] | |

| Rebellion breaks out in Sichuan[161] | ||

| 1212 | Floodwaters hit Zhejiang[171] | |

| 1213 | Rebellion breaks out in Sichuan[161] | |

| Floodwaters hit Zhejiang[171] | ||

| 1214 | Jin dynasty raids Song dynasty[173] | |

| Drought hits Zhejiang[171] | ||

| 1215 | Drought and locusts hit Zhejiang[171] | |

| 1216 | Earthquakes hit Sichuan[171] | |

| 1217 | spring | Jin dynasty invades Song dynasty but is repelled[174] |

| Rebellion breaks out in Sichuan[161] | ||

| Floodwaters hit Zhejiang[171] | ||

| 1219 | Jin dynasty invades Song dynasty but is repelled[175] | |

| Rebellion breaks out in Sichuan and is suppressed[176] |

1220s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1220 | Rebellion breaks out in Sichuan[161] | |

| Massive fires erupt in Lin'an[171] | ||

| 1221 | Jin dynasty invades Song dynasty but is repelled[177] | |

| Iron casing bombs are employed by Jin troops in the siege of Qi Prefecture (Hubei).[178] | ||

| 1224 | 17 September | Emperor Ningzong of Song dies and his adopted son Zhao Yun succeeds him as Emperor Lizong of Song[179] |

| Song and Jin cease hostilities[180] | ||

| 1225 | Rebels in Shandong invade the Song dynasty and are repelled[181] | |

| 1227 | September | Emperor Mozhu of Western Xia surrenders to the Mongol Empire and is promptly executed; so ends the Western Xia[182] |

1230s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1230 | Co-viative projectiles are added to fire lances.[183] | |

| 1231 | Song patrols kill a Mongol envoy and in retaliation the Mongols raid Sichuan[184] | |

| Massive fires erupt in Lin'an[185] | ||

| 1233 | summer | Song dynasty invades Jin dynasty[186] |

| 1234 | 9 February | Siege of Caizhou: Emperor Aizong of Jin abdicates to a distant relative, Hudun, who becomes Emperor Mo of Jin, and commits suicide; Emperor Mo of Jin is killed by the Mongols; so ends the Jin dynasty[187] |

| Mongols annihilate the Song army at Luoyang[188] | ||

| 1235 | Mongols raid the Song dynasty[189] | |

| Massive fires erupt in Lin'an[185] | ||

| 1236 | Mongols rout Song forces in Sichuan[189] | |

| 1237 | Large bombs requiring several hundred men to hurl using trebuchets are employed by Mongols in the siege of Anfeng (modern Shouxian, Anhui Province).[190] | |

| Massive fires erupt in Lin'an[185] | ||

| 1238 | Counterattacks by Song forces force Mongols to withdraw[191] |

1240s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1240 | Foot binding spreads to daughters and wives of officials[100] | |

| 1242 | Mongols raid Sichuan[192] | |

| 1243 | Mongols raid Sichuan[192] | |

| 1244 | Mongols raid Huainan[192] | |

| 1245 | Mongols occupy Shou Prefecture[193] | |

| Rockets are used during a military exercise conducted by the Song navy.[194] | ||

| 1246 | Mongols raid Huainan[192] | |

| 1247 | Issues of huizi to subsidize rising expenditures and declining revenues reach a value of 650,000,000 strings of cash, an increase by a factor of 25 over half a century[195][196] | |

| Qin Jiushao discovers Horner's method and introduces the zero symbol into Chinese mathematics[197][198] |

1250s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1250 | Annual registration for prefectural examinations reaches 400,000 candidates[30] | |

| 1252 | Mongol forces under the Chinese general Wang Dechen advance into Sichuan and occupy Li Prefecture[199] | |

| Massive fires erupt in Lin'an[185] | ||

| 1253 | Mongol forces occupy Li Prefecture[200] | |

| 1254 | Mongol raids on the northern Song border intensify[201] | |

| 1256 | summer | Möngke Khan declares war on the Song dynasty, citing imprisonment of Mongol envoys as casus belli[201] |

| The Bazi Bridge is completed in Shaoxing[202] | ||

| 1257 | Three-hundred thirty-three "fire emitting tubes" are produced in a Song arsenal in Jiankang Prefecture (Nanjing, Jiangsu).[203][204] | |

| Massive fires erupt in Lin'an[185] | ||

| 1258 | Mongols capture Chengdu[205] | |

| 1259 | January | Möngke Khan's forces take Ya Prefecture[200] |

| February | Siege of Diaoyu Castle: Möngke Khan's forces lay siege to Diaoyu Fortress[206] | |

| July | Siege of Diaoyu Castle: Möngke Khan calls off the siege of Diaoyu Fortress[207] | |

| August | Taghachar attacks Huainan[200] | |

| 12 August | Möngke Khan dies from dysentery or a wound inflicted by a Song trebuchet, forcing Mongol forces to withdraw from Song territory[208] | |

| September | Kublai Khan's forces cross the Yangtze and lays siege to Ezhou, however he receives news of Möngke Khan's death and Ariq Böke's mobilization, forcing hm to withdraw and deal with his brother[209] | |

| The History of Song describes a "fire-emitting lance" employing a pellet wad projectile which occludes the barrel. Some consider this to be the first bullet.[203][204] | ||

| The city of Qingzhou produces one to two thousand iron cased bomb shells a month and sends them in deliveries of ten to twenty thousand at a time to Xiangyang and Yingzhou.[210] | ||

| Floodwaters hit Zhejiang[185] |

1260s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1260 | 5 May | Kublai Khan convenes a kurultai at Kaiping, which elects him as ruler of the Mongol Empire; so ends the centralized Mongol Empire[211] |

| Kublai Khan's envoy Hao Jing proposes that the Song dynasty acknowledge Kublai as Son of Heaven in return for autonomy and gets jailed[212] | ||

| 1261 | Kublai Khan sends funds to Li Tan of Shandong to make war on the Song dynasty[213] | |

| 1262 | 22 February | Mongol-allied warlord of Shandong, Li Tan, defects to the Song dynasty[214] |

| August | Kublai Khan's Chinese generals Shi Tianze and Shi Chu crush Li Tan's forces and capture him; Li Tan is trampled to death by horses[213] | |

| 1263 | Massive fires erupt in Lin'an[185] | |

| 1264 | Emperor Lizong of Song dies and his nephew Zhao Qi succeeds him as Emperor Duzong of Song[215] | |

| Massive fires erupt in Lin'an[185] | ||

| A display of miniature rockets frightens the Song empress.[216] | ||

| The value of huizi collapses[196] | ||

| 1265 | Song dynasty and Mongol forces clash in Sichuan[212] | |

| 1268 | Battle of Xiangyang: Aju of the Mongols lays siege to Xiangyang[217] |

1270s

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1271 | Kublai Khan declares himself emperor of the Yuan dynasty[218] | |

| Chinese people start visiting Taiwan[219] | ||

| 1272 | Battle of Xiangyang: Riverine relief forces use fire lances to repel boarders and break the Mongol blockade of Xiangyang[220] | |

| 1273 | March | Battle of Xiangyang: Lü Wenhuan surrenders Xiangyang to Yuan[221] |

| 1274 | 12 August | Emperor Duzong of Song dies and his son Zhao Xian succeeds him as Emperor Gong of Song; Xie Daoqing becomes regent[222] |

| 1275 | January | Bayan's forces cross the Yangtze at Hankou[223] |

| March | Bayan's forces meet Jia Sidao in battle at Dingjiao Prefecture and annihilate his force using artillery equipment[223] | |

| Mongols conquer the Hanshui region[222] | ||

| 1276 | Mongol army annihilates a Song army near modern Guichi District[224] | |

| 22 March | Lin'an surrenders to the Mongols and Emperor Gong of Song is eventually moved to Dunhuang where he raises a family and becomes a monk[225] | |

| Yuan general of Uyghur descent, Arigh Kaya, conquers Hunan and Guangxi[226] | ||

| Yuan commander Sodu occupies Fuzhou[226] | ||

| 14 June | Song loyalists enthrone Zhao Shi, brother of Emperor Gong of Song, as Emperor Duanzong of Song[227] | |

| Reusable fire lance barrels made of metal are employed by the Song army.[228] | ||

| Fire lances are used by Song cavalry in combating Mongols.[220] | ||

| 1277 | April | Muslim superintendent of Quanzhou Pu Shougeng defects to Yuan [226] |

| A suicide bombing occurs in China when Song garrisons set off a large bomb, killing themselves.[229][230] | ||

| 1278 | February | Yuan commander Sodu occupies Guangzhou[226] |

| 9 May | Emperor Duanzong of Song dies in Guangnan and is succeeded by his brother Zhao Bing[231] | |

| 1279 | 19 March | Battle of Yamen: Mongol fleet annihilates the Song fleet and Zhao Bing dies at sea; so ends the Song dynasty[232] |

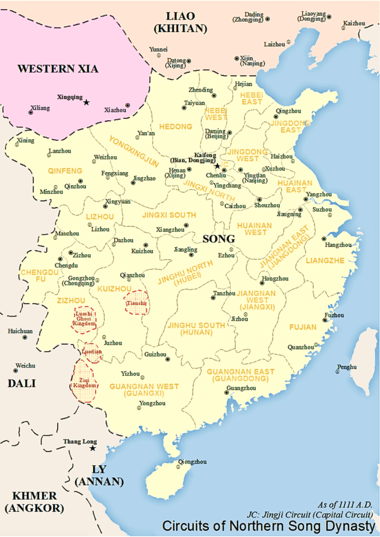

Gallery

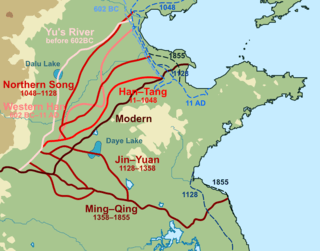

Yellow River course changes

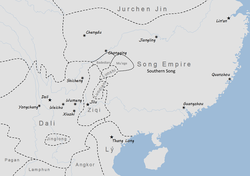

Yellow River course changes Liao dynasty invasion in 1004

Liao dynasty invasion in 1004 Lý dynasty, c. 1100

Lý dynasty, c. 1100

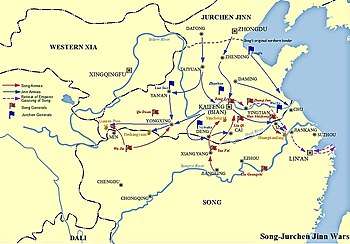

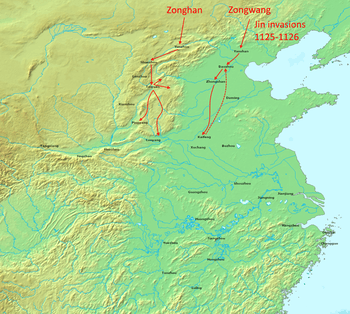

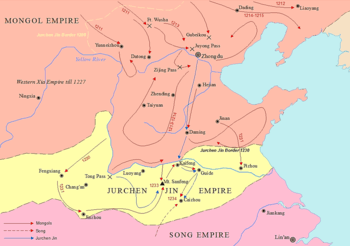

Jin–Song Wars, 1125-1126

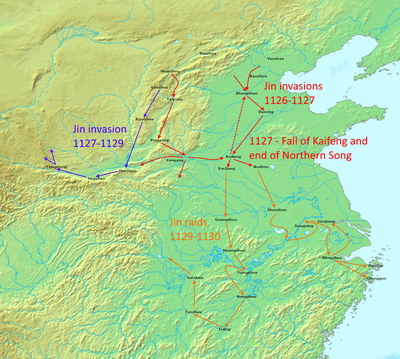

Jin–Song Wars, 1125-1126 Jin–Song Wars, 1126-1130

Jin–Song Wars, 1126-1130 Major Yellow River course changes

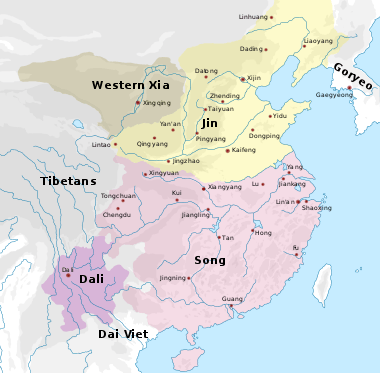

Major Yellow River course changes Southern Song in 1200

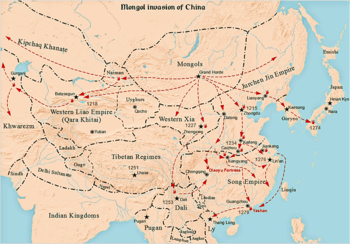

Southern Song in 1200 Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty

Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty

gollark: Hmm. It's very ☭. I dislike it.

gollark: So I should start randomly using it for normal traffic?

gollark: That seems excessive.

gollark: ····

gollark: ···

References

- Xiong 2009, p. cxviii.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 124.

- Needham, 1986h & p-460.

- Herman 2007, p. 39.

- Herman 2007, p. 43.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 247.

- Liang 2006.

- Needham 1986h, p. 280.

- Herman 2007, p. 40.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 228.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 242.

- Herman 2007, p. 42.

- Hobson 2004, p. 52.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 86.

- Walker 2012, p. 211-212.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 252.

- Wilkinson 2012, p. 910.

- Needham 1986c, p. 349-351.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 99.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 256.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 236.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 257.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 260.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 105.

- Andrade 2016, p. 32.

- Hobson 2004, p. 57.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 353.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 109-110.

- Mote 2003, p. 178.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 122.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 272.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 218.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 283.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 232.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 279.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 237.

- Needham 1986c, p. 97.

- 2009, p. 291.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 302.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 296.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 298.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 329.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 305.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 307.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 309.

- Wilkinson 2012, p. 911.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 314.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 122.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 318.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 127.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 315.

- Needham 1986f, p. 118-124.

- Ebrey 1999, p. 138.

- Andrade 2016, p. 41.

- Needham 1986f, p. 154.

- Needham 1986g, p. 254.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 123.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 325.

- "Iron Pagoda". China Culture. Archived from the original on 2007-08-06. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- Knapp 2008, p. 214.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 335.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 343.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 342.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 344.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 345.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 346.

- Kelly 2004, p. 4.

- Needham 1986c, p. 660.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 469.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 393.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 231.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 586.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 468.

- Taylor 2013, p. 81.

- Hartwell, Robert (March 1966). "Markets, Technology, and the Structure of Enterprise in the Development of the Eleventh-Century Chinese Iron and Steel Industry". The Journal of Economic History. 26 (1): 54. ISSN 0022-0507. JSTOR 2116001.

- Taylor 2013, p. 82.

- Taylor 2013, p. 84.

- Reilly 2012, p. 145.

- Jin 2016, p. 132.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 391.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 233.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 477.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 480.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 499.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 217.

- Jin 2016, p. 136.

- Taylor 2013, p. 85.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 507.

- Needham 1986b, p. 111.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 531.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 550.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 551.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 553.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 125.

- Pacey 1991, p. 7.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 597.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 614.

- "Han Chinese Footbinding". Textile Research Centre.

- Xu Ji 徐積 《詠蔡家婦》: 「但知勒四支,不知裹两足。」(translation: "knowing about arranging the four limbs, but not about binding her two feet); Su Shi 蘇軾 《菩薩蠻》:「塗香莫惜蓮承步,長愁羅襪凌波去;只見舞回風,都無行處踪。偷穿宮樣穩,並立雙趺困,纖妙說應難,須從掌上看。」

- Patricia Buckley Ebrey (1 December 1993). The Inner Quarters: Marriage and the Lives of Chinese Women in the Sung Period. University of California Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 9780520913486.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 196.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 599.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 128.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 598.

- Tsien 1985, p. 97.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 610.

- Kelly 2004, p. 2.

- Needham 1986g, p. 279.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 603.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 628.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 626.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 605.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 627.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 149.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 227.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 151.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 637.

- Andrade 2016, p. 34.

- Lorge 2005, p. 53.

- Andrade 2016, p. 34-35.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 643.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 229.

- Lu 1988.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 230.

- Andrade 2016, p. 38.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 655.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 665.

- Andrade 2016, p. 153-154.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 666.

- Needham 1986c, p. 476.

- Needham 1986f, p. 222.

- Chase 2003, p. 31.

- Lorge 2008, p. 33-34.

- Andrade 2016, p. 40.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 674.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 232.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 676.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 682.

- Mote 2003, p. 303.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 684.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 686.

- Beckwith 2009, p. 175.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 700.

- Knapp 2008, p. 244.

- Knapp 2008, p. 215.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 749.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 706.

- Andrade 2016, p. 39.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 708.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 717.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 244.

- Rubinstein 1999, p. 86.

- Knapp 1980, p. 6.

- Chia 2011, p. 241.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 752.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 753.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 754.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 760.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 768.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 772-773.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 833.

- Needham 1986b, p. 103.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 787.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 786.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 790.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 247.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 343.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 248.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 249.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 831.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 830.

- Needham 1986b, p. 50.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 822.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 259.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 827.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 832.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 829.

- Andrade 2016, p. 42.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 836.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 261.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 849.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 213.

- Needham 1986f, p. 230.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 852.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 906.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 856.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 264.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 82.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 864.

- Andrade 2016, p. 47.

- Twichett 2009, p. 865.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 867.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 383.

- Needham 1986f, p. 511.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 908.

- Kuhn 2009, p. 241.

- "Qin Jiushao". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- "10 MAJOR ACHIEVEMENTS OF SONG DYNASTY OF CHINA". learnodo-newtonic. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 405.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 410.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 409.

- Knapp 2008, p. 176.

- Andrade 2016, p. 51.

- Partington 1960, p. 246.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 869.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 870.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 410.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 411.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 422-423.

- Needham 1986f, p. 173-174.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 423.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 431.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 426.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 257.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 912.

- Needham 1986, p. 509.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 922.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 458.

- Andrade 2008f.

- Needham 1986f, p. 227.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 923.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 928.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 434.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 932.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 942-945.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 435.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 948.

- Needham 1986f, p. 228.

- Andrade 2016, p. 50-51.

- Partington 1960, p. 250, 244, 149.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 952.

- Twitchett 2009, p. 956.

Bibliography

- Andrade, Tonio (2008f), "Chapter 6: The Birth of Co-colonization", How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, Columbia University Press

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Asimov, M.S. (1998), History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO Publishing

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Barrett, Timothy Hugh (2008), The Woman Who Discovered Printing, Great Britain: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12728-7 (alk. paper)

- Beckwith, Christopher I (1987), The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages, Princeton University Press

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009), Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2

- Biran, Michal (2005), The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World, Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521842263

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Chase, Kenneth Warren (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9

- Chia, Lucille (2011), Knowledge and Text Production in an Age of Print: China, 900-1400, Brill

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005), Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History, Brill

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006), East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-618-13384-4

- Golden, Peter B. (1992), An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East, OTTO HARRASSOWITZ · WIESBADEN

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Warfare and History, London: Routledge, ISBN 0415239559

- Graff, David Andrew (2016), The Eurasian Way of War Military Practice in Seventh-Century China and Byzantium, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-46034-7.

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492, Barnes & Noble

- Herman, John E. (2007), Amid the Clouds and Mist China's Colonization of Guizhou, 1200–1700, Harvard University Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-02591-2

- Hobson, John M. (2004), The Eastern Origins of Western Civilization, Cambridge University Press

- Jin, Dengjian (2016), The Great Knowledge Transcendence: The Rise of Western Science and Technology Reframed, Palgrave Macmillan

- Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-03718-6.

- Knapp, Ronald G. (1980), China's Island Frontier: Studies in the Historical Geography of Taiwan, The University of Hawaii

- Knapp, Ronald G. (2008), Chinese Bridges: Living Architecture From China's Past. Singapore, Tuttle Publishing

- Kuhn, Dieter (2009), The Age of Confucian Rule, Harvard University Press

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964), The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1-2, Macmillan

- Lorge, Peter (2005), War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900–1795, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-96929-8

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Lu, Gwei-Djen (1988), "The Oldest Representation of a Bombard", Technology and Culture, 29: 594–605

- Luttwak, Edward N. (2009), The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Millward, James (2009), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press

- Mote, F. W. (2003), Imperial China: 900–1800, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674012127

- Needham, Joseph (1986a), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth, Taipei: Caves Books

- —— (1986g), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Engineering, Part 1, Physics, Taipei: Caves Books

- —— (1986b), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Engineering, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering, Taipei: Caves Books

- —— (1986c), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics, Taipei: Caves Books

- —— (1986d), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing, Taipei: Caves Books

- —— (1986e), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 4, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus, Theories and Gifts, Taipei: Caves Books

- —— (1986h), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 1, Botany, Cambridge University Press

- —— (1986f), Science & Civilisation in China, V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3

- Pacey, Arnold (1991), Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-year History, MIT Press

- Partington, J. R. (1960), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer & Sons.

- Partington, J. R. (1999), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5954-9

- Reilly, Kevin (2012), The Human Journey: A Concise Introduction to World History, Volume 1, Rowman & Littlefield

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013), Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, Brill

- Rubinstein, Murray A. (1999), Taiwan: A New History, East Gate Books

- Schafer, Edward H. (1985), The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A study of T'ang Exotics, University of California Press

- Shaban, M. A. (1979), The ʿAbbāsid Revolution, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29534-3

- Sima, Guang (2015), Bóyángbǎn Zīzhìtōngjiàn 54 huánghòu shīzōng 柏楊版資治通鑑54皇后失蹤, Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī, ISBN 957-32-0876-8

- Skaff, Jonathan Karam (2012), Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580-800 (Oxford Studies in Early Empires), Oxford University Press

- Standen, Naomi (2007), Unbounded Loyalty Frontier Crossings in Liao China, University of Hawai'i Press

- Taylor, K.W. (2013), A History of the Vietnamese, Cambridge University Press

- Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985), Paper and Printing, Needham, Joseph Science and Civilization in China:, vol. 5 part 1, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-08690-6

- Twitchett, Denis C. (1979), The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 3, Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Cambridge University Press

- Twitchett, Denis (1994), "The Liao", The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6, Alien Regime and Border States, 907-1368, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 43–153, ISBN 0521243319

- Twitchett, Denis (2009), The Cambridge History of China Volume 5 The Sung dynasty and its Predecessors, 907-1279, Cambridge University Press

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012), East Asia: A New History, AuthorHouse

- Wang, Zhenping (2013), Tang China in Multi-Polar Asia: A History of Diplomacy and War, University of Hawaii Press

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012), Chinese History: A New Manual, Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2015), Chinese History: A New Manual, 4th edition, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center distributed by Harvard University Press, ISBN 9780674088467

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2000), Sui-Tang Chang'an: A Study in the Urban History of Late Medieval China (Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies), U OF M CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES, ISBN 0892641371

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0810860538

- Xu, Elina-Qian (2005), HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PRE-DYNASTIC KHITAN, Institute for Asian and African Studies 7

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992), Turkic peoples, 中国社会科学出版社

- Yuan, Shu (2001), Bóyángbǎn Tōngjiàn jìshìběnmò 28 dìèrcìhuànguánshídài 柏楊版通鑑記事本末28第二次宦官時代, Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī, ISBN 957-32-4273-7

- Yule, Henry (1915), Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route, Hakluyt Society

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.