Su Shi

Su Shi (Chinese: 蘇軾 / 苏轼;8 January 1037 – 24 August 1101), courtesy name Zizhan (Chinese: 子瞻), art name Dongpo (Chinese: 東坡), was a Chinese calligrapher, gastronome, painter, pharmacologist, poet, politician, and writer of the Song dynasty. A major personality of the Song era, Su was an important figure in Song Dynasty politics, aligning himself with Sima Guang and others, against the New Policy party led by Wang Anshi.

Su Shi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait of Su Dongpo by Zhao Mengfu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 19th day of the 12th month of the 3rd Year in the Jingyou era of Emperor Renzong of Song 8 January 1037[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 28th day of the 7th month of the 1st Year in the Jianzhongjingguo era of Emperor Huizong of Song 24 August 1101 (aged 64) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Minister of Rites, Poet, Essayist, Painter, Calligrapher, Statesman | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notable work | Former and Latter Odes on the Red Cliffs (前赤壁賦) The Cold Food Observance (寒食帖) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent(s) | Su Xun (father) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Su Zhe (brother) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 蘇軾 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 苏轼 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zizhan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 子瞻 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Little Forward-Looking One | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dongpo Jushi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 東坡居士 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 东坡居士 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | East Slope Householder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Su Dongpo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 蘇東坡 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 苏东坡 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Su Shi is widely regarded as one of the most accomplished figures in classical Chinese literature, having produced some of the most well-known poems, lyrics, prose, and essays. Su Shi was famed as an essayist, and his prose writings lucidly contribute to the understanding of topics such as 11th-century Chinese travel literature or detailed information on the contemporary Chinese iron industry. His poetry has a long history of popularity and influence in China, Japan, and other areas in the near vicinity and is well known in the English-speaking parts of the world through the translations by Arthur Waley, among others. In terms of the arts, Su Shi has some claim to being "the pre-eminent personality of the eleventh century."[2] Dongpo pork, a prominent dish in Hangzhou cuisine, is named in his honor.

Life

Su Shi was born in Meishan, near Mount Emei today Sichuan province. His brother Su Zhe and his father Su Xun were both famous literati. His given name, Shi (轼), refers to the crossbar railing at the front of a chariot; Su Xun felt that the railing was a humble, but indispensable, part of a carriage.

Su's early education was conducted under a Taoist priest at a local village school. Later his educated mother took over. Su married at the age of 17. Su and his younger brother (Zhe) had a close relationship,[3] and in 1057, when Su was 19, he and his brother both passed the (highest-level) civil service examinations to attain the degree of jinshi, a prerequisite for high government office.[4] His accomplishments at such a young age attracted the attention of Emperor Renzong, and also that of Ouyang Xiu, who became Su's patron thereafter. Ouyang had already been known as an admirer of Su Xun, sanctioning his literary style at court and stating that no other pleased him more.[5] When the 1057 jinshi examinations were given, Ouyang Xiu required—without prior notice—that candidates were to write in the ancient prose style when answering questions on the Confucian classics.[5] The Su brothers gained high honors for what were deemed impeccable answers and achieved celebrity status,[5] especially in the case of Su Shi's exceptional performance in the subsequent 1061 decree examinations.

Beginning in 1060 and throughout the following twenty years, Su held a variety of government positions throughout China; most notably in Hangzhou, where he was responsible for constructing a pedestrian causeway across the West Lake that still bears his name: sudi (苏堤, 蘇堤, Su causeway). He had served as a magistrate in Mi Prefecture, which is located in modern-day Zhucheng County of Shandong province. Later, when he was governor of Xuzhou, he wrote a memorial to the throne in 1078 complaining about the troubling economic conditions and potential for armed rebellion in Liguo Industrial Prefecture, where a large part of the Chinese iron industry was located.[6][7]

Su Shi was often at odds with a political faction headed by Wang Anshi. Su Shi once wrote a poem criticizing Wang Anshi's reforms, especially the government monopoly imposed on the salt industry.[8] The dominance of the reformist faction at court allowed the New Policy Group greater ability to have Su Shi exiled for political crimes. The claim was that Su was criticizing the emperor, when in fact Su Shi's poetry was aimed at criticizing Wang's reforms. It should be said that Wang Anshi played no part in this action against Su, for he had retired from public life in 1076 and established a cordial relationship with Su Shi.[8] Su Shi's first remote trip of exile (1080–1086) was to Huangzhou, Hubei. This post carried a nominal title, but no stipend, leaving Su in poverty. During this period, he began Buddhist meditation. With help from a friend, Su built a small residence on a parcel of land in 1081. Su Shi lived at a farm called Dongpo ('Eastern Slope'), from which he took his literary pseudonym. While banished to Hubei province, he grew fond of the area he lived in; many of the poems considered his best were written in this period.[4] His most famous piece of calligraphy, Han Shi Tie, was also written there. In 1086, Su and all other banished statesmen were recalled to the capital due to the ascension of a new government.[9] However, Su was banished a second time (1094–1100) to Huizhou (now in Guangdong province) and Hainan island.[4] In 1098 the Dongpo Academy in Hainan was built on the site of the residence that he lived in whilst in exile.

Although political bickering and opposition usually split ministers of court into rivaling groups, there were moments of non-partisanship and cooperation from both sides. For example, although the prominent scientist and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095) was one of Wang Anshi's most trusted associates and political allies, Shen nonetheless befriended Su Shi. Su Shi was aware that it was Shen Kuo who, as regional inspector of Zhejiang, presented Su Shi's poetry to the court sometime between 1073 and 1075 with concern that it expressed abusive and hateful sentiments against the Song court.[10] It was these poetry pieces that Li Ding and Shu Dan later utilized in order to instigate a law case against Su Shi, although until that point Su Shi did not think much of Shen Kuo's actions in bringing the poetry to light.[10]

After a long period of political exile, Su received a pardon in 1100 and was posted to Chengdu. However, he died in Changzhou, Jiangsu province after his period of exile and while he was en route to his new assignment in the year 1101.[4] Su Shi was 64 years old.[9] After his death he gained even greater popularity, as people sought to collect his calligraphy, paintings depicting him, stone inscriptions marking his visit to numerous places, and built shrines in his honor.[4] He was also depicted in artwork made posthumously, such as in Li Song's (1190–1225) painting of Su traveling in a boat, known as Su Dongpo at Red Cliff, after Su Song's poem written about a 3rd-century Chinese battle.[4]

Family

Su Shi had three wives. His first wife was Wang Fu (王弗, 1039–1065), an astute, quiet lady from Sichuan who married him at the age of sixteen. She died 13 years later in 1065, on the second day of the fifth Chinese lunar month (Gregorian calendar June 14), after bearing him a son, Su Mai (蘇邁). Heartbroken, Su wrote a memorial for her (《亡妻王氏墓志銘》), stating Fu was not just a virtuous wife but advised him frequently on the integrity of his acquaintances when he was an official.

Ten years after the death of his first wife, Su composed a (ci) poem after dreaming of the deceased Fu in the night at Mi Prefecture. The poem, To the tune of 'Of Jinling' (江城子), remains one of the most famous poems Su wrote.[11][12]

In 1068, two years after Wang Fu's death, Su married Wang Runzhi (王閏之, 1048–93), cousin of his first wife, and 11 years his junior. Wang Runzhi spent the next 15 years accompanying Su through his ups and downs in officialdom and political exile. Su praised Runzhi for being an understanding wife who treated his three sons equally (his eldest, Su Mai(苏迈,蘇邁), was born by Fu). Once, Su was angry with his young son for not understanding his unhappiness during his political exile. Wang chided Su for his silliness, prompting Su to write the domestic poem Young Son (《小兒》).

Wang Runzhi died in 1093, at forty-six, after bearing Su two sons, Su Dai (苏迨,蘇迨) and Su Guo (苏过,蘇過). Overcame with grief, Su expressed his wish to be buried with her in her memorial (see memorial 《祭亡妻同安郡君文》). On his second wife's second birthday after her death, Su wrote another ci poem, To the tune of 'Butterflies going after Flowers' (《蝶戀花》), for her.

Su's third wife, Wang Zhaoyun (王朝雲, 1062–1095) was his handmaiden who was a former Qiantang singing artiste. Wang was only about ten (eleven sui) when she became his personal slave.[13] After she taught, herself to read though she was formerly illiterate. Zhaoyun was probably the most famous of Su's companions. Su's friend Qin Guan wrote a poem, A Gift for Dongpo's concubine Zhaoyun (《贈東坡妾朝雲》), praising her beauty and lovely voice. Su dedicated a number of his poems to Zhaoyun, like To the Tune of 'Song of the South’《南歌子》, Verses for Zhaoyun (《朝雲詩》), To the Tune of 'The Beauty Who asks One to Stay' (《殢人嬌·贈朝雲》), To the Tune of 'The Moon at Western Stream' 《西江月》. Zhaoyun remained a faithful companion to Su after Runzhi's death, but died of illness on 13 August 1095 (紹聖三年七月五日) at Huizhou.[14] Zhaoyun bore Su a son, Su Dun (蘇遁) on 15 November 1083, who died in his infancy. After Zhaoyun's death, Su never married again.

Being a government official in a family of officials, Su was often separated from his loved ones depending on his posting. In 1078, he was serving as prefect of Suzhou. His beloved younger brother was able to join him for the mid-autumn festival, which inspired the poem "Mid-Autumn Moon" reflecting on the preciousness of time with family. It was written to be sung to the tune of "Yang Pass."[3]

- As evening clouds withdraw a clear cool air floods in

- the jade wheel passes silently across the Silver River

- this life this night has rarely been kind

- where will we see this moon next year

- (translation by Red Pine)

Su Shi had three adult sons, the eldest son being Su Mai (蘇邁), who would also become a government official by 1084.[15] Su Dai (蘇迨) and Su Guo (蘇過) are his other sons. When Su Shi died in 1101, his younger brother Su Zhe (蘇轍) buried him alongside second wife Wang Runzhi according to his wishes.

Work

Poetry

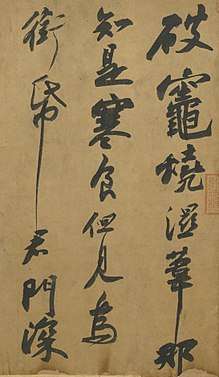

Around 2,700 of Su Song's poems have survived, along with 800 written letters.[4] Su Dongpo excelled in the shi, ci and fu forms of poetry, as well as prose, calligraphy and painting. Some of his notable works include the First and Second Chibifu (赤壁賦 The Red Cliffs, written during his first exile), Nian Nu Jiao: Chibi Huai Gu (念奴嬌.赤壁懷古 Remembering Chibi, to the tune of Nian Nu Jiao) and Shui diao ge tou (水調歌頭 Remembering Su Zhe on the Mid-Autumn Festival, 中秋节,中秋節). The two former poems were inspired by the 3rd century naval battle of the Three Kingdoms era, the Battle of Chibi in the year 208. The bulk of his poems are in the shi style, but his poetic fame rests largely on his 350 ci style poems. Su Shi also founded the haofang school, which cultivated an attitude of heroic abandon. In both his written works and his visual art, he combined spontaneity, objectivity and vivid descriptions of natural phenomena. Su Shi wrote essays as well, many of which are on politics and governance, including his Liuhoulun (留侯論). His popular politically charged poetry was often the reason for the wrath of Wang Anshi's supporters towards him, culminating with the Crow Terrace Poetry Trial of 1079. He also wrote poems on Buddhist topics, including a poem later extensively commented on by Eihei Dōgen, the founder of the Japanese Sōtō school of Zen, in a chapter of his work Shōbōgenzō entitled The Sounds of Valley Streams, the Forms of Mountains.[16]

Travel record literature

Su Shi also wrote of his travel experiences in 'daytrip essays',[17] which belonged in part to the popular Song era literary category of 'travel record literature' (youji wenxue) that employed the use of narrative, diary, and prose styles of writing.[18] Although other works in Chinese travel literature contained a wealth of cultural, geographical, topographical, and technical information, the central purpose of the daytrip essay was to use a setting and event in order to convey a philosophical or moral argument, which often employed persuasive writing.[17] For example, Su Shi's daytrip essay known as Record of Stone Bell Mountain investigates and then judges whether or not ancient texts on 'stone bells' were factually accurate.[19]

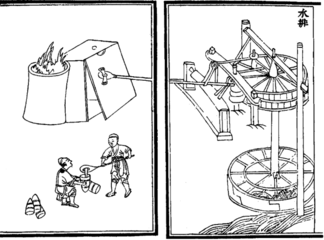

A memorial concerning the iron industry

While acting as Governor of Xuzhou, Su Shi in 1078 AD wrote a memorial to the imperial court about problems faced in the Liguo Industrial Prefecture which was under his watch and administration. In an interesting and revealing passage about the Chinese iron industry during the latter half of the 11th century, Su Shi wrote about the enormous size of the workforce employed in the iron industry, competing provinces that had rival iron manufacturers seeking favor from the central government, as well as the danger of rising local strongmen who had the capability of raiding the industry and threatening the government with effectively armed rebellion. It also becomes clear in reading the text that prefectural government officials in Su's time often had to negotiate with the central government in order to meet the demands of local conditions.[20]

Technical issues of hydraulic engineering

During the ancient Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) of China, the sluice gate and canal lock of the flash lock had been known.[21] By the 10th century the latter design was improved upon in China with the invention of the canal pound lock, allowing different adjusted levels of water along separated and gated segments of a canal.[22] This innovation allowed for larger transport barges to pass safely without danger of wrecking upon the embankments, and was an innovation praised by those such as Shen Kuo (1031–1095).[23] Shen also wrote in his Dream Pool Essays of the year 1088 that, if properly used, sluice gates positioned along irrigation canals were most effective in depositing silt for fertilization.[24] Writing earlier in his Dongpo Zhilin of 1060, Su Shi came to a different conclusion, writing that the Chinese of a few centuries past had perfected this method and noted that it was ineffective in use by his own time.[25]

Although Su Shi made no note of it in his writing, the root of this problem was merely the needs of agriculture and transportation conflicting with one another.[25]

Gastronome

Su is called one of the four classical gastronomes. The other three are Ni Zan (1301–74), Xu Wei (1521–93), and Yuan Mei (1716–97).[26] There is a legend, for which there is no evidence, that by accident he invented Dongpo pork, a famous dish in later centuries. Lin Hsiang Ju and Lin Tsuifeng in their scholarly Chinese Gastronomy give a recipe, "The Fragrance of Pork: Tungpo Pork", and remark that the "square of fat is named after Su Dongpo, the poet, for unknown reasons. Perhaps it is just because he would have liked it."[27] A story runs that once Su Dongpo decided to make stewed pork. Then an old friend visited him in the middle of the cooking and challenged him to a game of Chinese chess. Su had totally forgotten the stew, which in the meantime had now become extremely thick-cooked, until its very fragrant smell reminded him of it.

Su, to explain his vegetarian inclinations, said that he never had been comfortable with killing animals for his dinner table, but had a craving for certain foods, such as clams, so he couldn't desist. When he was imprisoned his views changed. "Since my imprisonment I have not killed a single thing... having experienced such worry and danger myself, when I felt just like a fowl waiting in the kitchen, I can no longer bear to cause any living creature to suffer immeasurable fright and pain simply to please my palate."[28]

See also

- Chinese literature

- Chinese poetry

- Classical Chinese poetry

- Crow Terrace Poetry Trial

- Culture of the Song Dynasty

- History of the Song Dynasty

- Shen Kuo

- Song poetry

- Tao Yuanming

- Su Shi's destiny quote

- Technology of the Song Dynasty

- Wang Shen

Notes

- 《献曲求诗》:元丰五年十二月十九日东坡生日,置酒赤壁矶下,踞高峰,酒酣,笛声起于江上。客有郭、尤二生,颇知音,谓坡曰:“笛声有新意,非俗工也。”使人问之,则进士李委闻坡生日,作南曲目《鹤南飞》以献。呼之使前,则青巾紫裘腰笛而已。既奏新曲,又快作数弄,嘹然有穿云石之声,坐客皆引满醉倒。委袖出嘉纸注一幅曰:“吾无求于公,得一绝句足矣。”坡笑而从之。

- Murck (2000), p. 31.

- Red Pine, Poems of the Masters, Copper Canyon Press, 2003.

- Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 140.

- Hymes, 61.

- Wagner, 178

- Hegel, 13

- Ebrey, East Asia, 164.

- Hegel, 14

- Hartman, 22.

- Dreaming of My Deceased Wife on the Night of the 20th Day of the First Month

- "Su Shi's poetry at Chinapage.org". Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- http://www.ihp.sinica.edu.tw/~twsung/song/thesis/th14.pdf

- See Su Su's 悼朝雲詩

- Hargett, 75.

- Bielefeldt, Carl (2013), "Sound of the Stream, Form of the Mountain: Keisei Sanshoku" (PDF), Dharma Eye, Sotoshu Shumucho (31): 21–29

- Hargett, 74.

- Hargett, 67-73.

- Hargett, 74–76

- Wagner, 178–179

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 344-350.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 350-351.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 351-352.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 230-231.

- Needham Volume 4, Part 3, 230.

- Endymion Wilkinson, Chinese History: A Manual (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, Rev. and enl., 2000): 634.

- Hsiang-Ju Lin and Tsuifeng Lin, with a Foreword and Introduction by Lin Yutang, Chinese Gastronomy. New York,: Hastings House, 1969 ISBN 0-8038-1131-4. Various reprints, p 55.

- Egan, Word, Image, and Deed, p. 52-53.

- https://www.christies.com/auctions/sushi

Translations

- Watson, Burton (translator). Selected Poems of Su Tung-p'o (English only) (Copper Canyon Press, 1994)

- Xu Yuanchong (translator). Selected Poems of Su Shi. (Chinese with English translations). Hunan: Hunan People's Publishing House, 2007.

Bibliography

- Ebrey, Walthall, Palais (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-13384-4.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43519-6 (hardback); ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Egan, Ronald. Word, Image, and Deed in the Life of Su Shi. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press, Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series, 1994. ISBN 0-674-95598-6.

- Fuller, Michael Anthony. The Road to East Slope: The Development of Su Shi's Poetic Voice. Stanford University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8047-1587-4.

- Hargett, James M. "Some Preliminary Remarks on the Travel Records of the Song Dynasty (960-1279)," Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR) (July 1985): 67-93.

- Hartman, Charles. "Poetry and Politics in 1079: The Crow Terrace Poetry Case of Su Shih," Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR) (Volume 12, 1990): 15–44.

- Hatch, George. (1993) "Su Hsun's Pragmatic Statecraft" in Ordering the World : Approaches to State and Society in Sung Dynasty China, ed. Robert P. Hymes, 59–76. Berkeley: Berkeley University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07691-4.

- Hegel, Robert E. "The Sights and Sounds of Red Cliffs: On Reading Su Shi," Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR) (Volume 20 1998): 11-30.

- Lin, Yutang. The Gay Genius: The Life and Times of Su Tungpo. J. Day Co., 1947. ISBN 0-8371-4715-8.

- Murck, Alfreda (2000). Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-00782-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 1, Introductory Orientations. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Sivin, Nathan (1995). "Shen Kua." In Sivin's Science in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections, text III: 1-53. Haldershot (Hampshire, England), and Burlington (Vermont, USA): VARIORUM, Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-86078-492-4.

- Wagner, Donald B. "The Administration of the Iron Industry in Eleventh-Century China," Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient (Volume 44 2001): 175-197.

- Yang, Vincent. Nature and Self: A Study of the Poetry of Su Dongpo, With Comparisons to the Poetry of William Wordsworth (American University Studies, Series III). Peter Lang Pub Inc, 1989. ISBN 0-8204-0939-1.

Further reading

- Jacques, Rob. Adagio for Su Tung-p'o: Poems on How Consciousness Uses Flesh to Float through Space/Time. (Fernwood Press, 2019) ISBN 978-1-59498-065-7. Using lines from Su Tung-p'o's poems as epigraphs, Jacques explores the 11th Century Chinese poet's metaphysical views on life, love and eternity from a 21st Century perspective.

- Wang, Yugen. "The Limits of Poetry as Means of Social Criticism: The 1079 Literary Inquisition against Su Shi Revisited." Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. Volume 41, 2011. pp. 29–65. 10.1353/sys.2011.0028. Available at Project MUSE.

External links

- Su Shi and his Calligraphy Gallery at China Online Museum

- Works by or about Su Shi at Internet Archive

- Works by Su Shi at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Su Shi: Poems

- Poems by Su Shi

- Su Shi Poems in English