Operation Mistral 2

Operation Mistral 2, officially codenamed Operation Maestral 2, was a Croatian Army (HV) and Croatian Defence Council (HVO) offensive in western Bosnia and Herzegovina on 8–15 September 1995 as part of the Bosnian War. Its objective was to create a security buffer between Croatia and positions held by the Bosnian Serb Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) and to put the largest Bosnian Serb-held city, Banja Luka, in jeopardy by capturing the towns of Jajce, Šipovo and Drvar. The combined HV and HVO forces were under the overall command of HV Major General Ante Gotovina.

| Operation Maestral 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Bosnian War | |||||||||

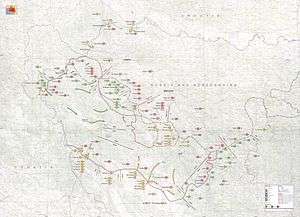

Objectives of Operation Maestral 2 ( | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

6 Guards brigades 3 reserve brigades 6 Home Guard regiments 2 Guards battalions |

1 motorised brigade 5 infantry brigades 1 armoured battalion | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

74 killed 226 wounded | Unknown | ||||||||

|

Serb civilian casualties: 655 civilians killed and 40,000–125,000 displaced (Serb claim) 20,000 civilians displaced (UN claim) | |||||||||

The operation commenced during a North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) air campaign against the VRS codenamed Operation Deliberate Force, targeting VRS air defences, artillery positions and storage facilities largely in the area of Sarajevo, but also elsewhere in the country. Days after commencement of the offensive, the VRS positions to the right and to the left of the HV and the HVO advance were also attacked by the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) in Operation Sana. The offensive achieved its objectives and set the stage for further advances of the HV, HVO and ARBiH towards Banja Luka, contributing to the resolution of the war.

There is disagreement among scholars as to whether the offensive, together with Operation Sana, or NATO airstrikes contributed more towards the resolution of the Bosnian War, and to what extent ARBiH, HVO and HV advances were aided by NATO airstrikes. Operation Mistral 2 resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Bosnian Serb civilians, as well as the displacement of tens of thousands of others. In 2011, five former Croatian military personnel were convicted of war crimes for the summary execution of five Bosnian Serb soldiers and a civilian during the operation. In 2016, Bosnian Serb officials filed a criminal complaint against the Croatian Minister of Defence, Damir Krstičević, alleging that he had committed war crimes during the offensive.

Background

As the Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslovenska narodna armija – JNA) withdrew from Croatia following the acceptance and start of implementation of the Vance plan, its 55,000 officers and soldiers born in Bosnia and Herzegovina were transferred to a new Bosnian Serb army, which was later renamed the Army of Republika Srpska (Vojska Republike Srpske – VRS). This re-organisation followed the declaration of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 9 January 1992, ahead of the referendum on the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina that took place between 29 February and 1 March 1992. This declaration would later be cited by the Bosnian Serbs as a pretext for the Bosnian War.[1] Bosnian Serbs began fortifying the capital, Sarajevo, and other areas on 1 March 1992. On the following day, the first fatalities of the war were recorded in Sarajevo and Doboj. In the final days of March, Bosnian Serb forces bombarded Bosanski Brod with artillery, resulting in a cross-border operation by the Croatian Army (Hrvatska vojska – HV) 108th Brigade.[2] On 4 April 1992, JNA artillery began shelling Sarajevo.[3] There were other examples of the JNA directly supported the VRS,[4] such as during the capture of Zvornik in early April 1992, when the JNA provided artillery support from Serbia, firing across the Drina River.[5] At the same time, the JNA attempted to defuse the situation and arrange negotiations elsewhere in the country.[4]

The JNA and the VRS in Bosnia and Herzegovina faced the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Armija Republike Bosne i Hercegovine – ARBiH) and the Croatian Defence Council (Hrvatsko vijeće obrane – HVO), reporting to the Bosniak-dominated central government and the Bosnian Croat leadership respectively, as well as the HV, which occasionally supported HVO operations.[2] In late April 1992, the VRS was able to deploy 200,000 troops, hundreds of tanks, armoured personnel carriers (APCs) and artillery pieces. The HVO and the Croatian Defence Forces (Hrvatske obrambene snage – HOS) could field approximately 25,000 soldiers and a handful of heavy weapons, while the ARBiH was largely unprepared with nearly 100,000 troops, small arms for less than a half of their number and virtually no heavy weapons.[6] Arming of the various forces was hampered by a United Nations (UN) arms embargo that had been introduced in September 1991.[7] By mid-May 1992, when those JNA units which had not been transferred to the VRS withdrew from Bosnia and Herzegovina to the newly declared Federal Republic of Yugoslavia,[5] the VRS controlled approximately 60 percent of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[8] The extent of VRS control was extended to about 70 percent of the country by the end of 1992.[9]

Prelude

By 1995, the ARBiH and the HVO had developed into better-organised forces employing comparably large numbers of artillery pieces and good defensive fortifications. The VRS was not capable of penetrating their defences even where its forces employed sound military tactics, for instance in the Battle of Orašje in May and June 1995.[10] After recapture of the bulk of the Republic of Serb Krajina (the Croatian Serb-controlled areas of Croatia) in Operation Storm in August 1995, the HV shifted its focus to western Bosnia and Herzegovina. The shift was motivated by a desire to create a security zone along the Croatian border, establish Croatia as a regional power and gain favours with the West by forcing an end to the Bosnian War. The government of Bosnia and Herzegovina welcomed the move as it contributed to their goal of gaining control over western Bosnia and the city of Banja Luka—the largest city in the Bosnian Serb-held territory.[11]

In the final days of August 1995, NATO launched Operation Deliberate Force—an air campaign targeting the VRS. This campaign was launched in response to the second Markale massacre of 28 August, which came on the heels of the Srebrenica massacre.[12] Airstrikes began on 30 August, initially targeting VRS air defences, and striking targets near Sarajevo. The campaign was briefly suspended on 1 September[13] and its scope was expanded to target artillery and storage facilities around the city.[14] The bombing resumed on 5 September, and its scope extended to VRS air defences near Banja Luka by 9 September as NATO had nearly exhausted its list of targets near Sarajevo. On 13 September, the Bosnian Serbs accepted NATO's demand for the establishment of an exclusion zone around Sarajevo and the campaign ceased.[15]

Order of battle

As the NATO bombing generally targeted VRS around Sarajevo, western Bosnia remained relatively calm following Operation Storm, except for probing attacks launched by the VRS, HVO or ARBiH near Bihać, Drvar and Glamoč. At the time the HV, HVO and ARBiH were planning a joint offensive in the region.[15] The main portion of the offensive was codenamed Operation Maestral (Croatian name for maestro wind),[16] or more accurately Operation Maestral 2. Within a month,[17] the HV and HVO had planned an operation to capture the towns of Jajce, Šipovo and Drvar, and position their forces to threaten Banja Luka. Major General Ante Gotovina was placed in command of the combined HV and HVO forces earmarked for the offensive.[16]

The forces were deployed in three groups. Operational Group (OG) North, tasked with capturing Šipovo and Jajce, consisted of 11,000 troops and included the best units available to Gotovina—the 4th Guards and the 7th Guards Brigades, the 1st Croatian Guards Brigade (1. hrvatski gardijski zdrug – 1st HGZ) of the HV and three HVO guards brigades. The rest of the force was organised into OG West and OG South, and consisted of five HV Home Guard regiments and three reserve infantry brigades. These two groups were to pin down the troops of the VRS 2nd Krajina Corps in the vicinity of Drvar, and attempt to advance on the town. Once OG North had completed its tasks, it was to turn back and capture Drvar. Gotovina's forces were deployed between the ARBiH 5th Corps on their left, and the 7th Corps on their right. The ARBiH forces were to advance on the flanks of the HV and the HVO, in a separate but coordinated offensive codenamed Operation Sana.[16][18]

In the area of the combined HV and HVO offensive, the VRS had its 2nd Krajina Corps, commanded by Major General Radivoje Tomanić, and the 30th Infantry Division of the 1st Krajina Corps, commanded by Major General Momir Zec. Tomanić, who set up his headquarters in Drvar, was in overall command in western Bosnia. Tomanić and Zec commanded a combined force of approximately 22,000 troops. They considered the ARBiH to be a greater threat in the area and only deployed between 5,000 and 6,000 troops directly against the HV, consisting of one motorised and six infantry or light infantry brigades fielded along the frontline and one brigade in reserve.[16]

| Group | Unit | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| North | 4th Guards Brigade | HV units, under direct command of Major General Ante Gotovina; The 81st Battalion not deployed initially |

| 7th Guards Brigade | ||

| 1st Croatian Guards Brigade | ||

| General Staff Reconnaissance Sabotage Company | ||

| 81st Guards Battalion | ||

| 1st Guards Brigade | HVO units, under command of Brigadier Željko Glasnović | |

| 2nd Guards Brigade | ||

| 3rd Guards Brigade | ||

| 60th Guards Airborne Battalion | ||

| 22nd Sabotage Detachment | ||

| Special police of the Ministry of Interior of Herzeg-Bosnia | ||

| South | 6th Home Guard Regiment | HV units, under command of Brigadier Ante Kotromanović |

| 126th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 141st Infantry Brigade | ||

| West | 7th Home Guard Regiment | HV units, under command of Brigadier Mladen Fuzul |

| 15th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 134th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 142nd Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 112th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 113th Infantry Brigade |

| Area | Unit | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Drvar | 1st Drvar Light Infantry Brigade | South and southwestern approaches to Drvar |

| 1st Drina Light Infantry Brigade | Southeastern approaches to Drvar; Units formed from elements drawn from most of the Drina Corps brigades and deployed to western Bosnia as reinforcements | |

| 2nd Drina Light Infantry Brigade | ||

| 3rd Drina Light Infantry Brigade | ||

| 9th Grahovo Light Infantry Brigade | Remnants only; The bulk of the brigade had been destroyed in Operation Summer '95 | |

| Mlinište–Vitorog | 3rd Serbian Brigade | Reinforced brigade |

| 7th Kupres-Šipovo Motorised Brigade | Augmented by elements of the 30th Division | |

| 1st Armoured Brigade | One battalion only; Not initially deployed |

Timeline

First stage: 8–11 September

The first stage of the offensive was planned to overcome VRS defences extending across mountains north of Glamoč, guarding southern approaches to Šipovo and Jajce.[16] The attack was launched in the morning of 8 September. The 7th and the 4th Guards Brigades spearheaded the attack, striking towards the Mlinište Pass and Jastrebnjak Hill respectively.[24] The first line of VRS defences was breached by 10:00, which allowed the 1st HGZ to push through the 4th Guards Brigade and outflank Mount Vitorog and the particularly strong VRS defences there. The 1st HGZ was quickly reinforced by the 60th Guards Battalion and the special police in attacks against the VRS positions on Vitorog. The farthest advance achieved on the initial day of the offensive was achieved by the 4th Guards Brigade, which advanced 5 kilometres (3.1 miles). The 7th Guards Brigade and the 1st HGZ advanced considerably less distance, while the supporting efforts of OG South and OG West launched that day against Drvar made little progress.[22]

On 9 September, the HV and HVO defeated the bulk of the main VRS defences of the 3rd Serbian and 7th Motorised Brigades, achieving a key breakthrough. The 1st HGZ pushed back the VRS from Vitorog, and the 7th Guards Brigade advanced 8 kilometres (5.0 miles), capturing the Mlinište Pass, while the 4th Guards Brigade secured Jastrebnjak Hill. The next day, the HV and the HVO were only able to advance 2 kilometres (1.2 miles), as the VRS deployed a battalion of M-84 tanks detached from the 1st Armoured Brigade. At this point, the HV and the HVO had achieved the objectives of the first stage of the offensive.[22] That day, the 7th Corps of the ARBiH launched its attack on the right flank of the HV and the HVO assault. It engaged VRS elements tenaciously defending Donji Vakuf.[25]

On 11 September, OG North paused offensive operations while the 4th and 7th Guards Brigades moved into reserve. They were replaced with the 1st and the 2nd Guards Brigades of the HVO, which became the spearhead of OG North. A probing attack by the 2nd Guards Brigade achieved some gains towards Jajce along the rim of the Kupres Plateau. OGs South and West made another effort to capture Drvar, but were beaten back by VRS infantry supported by artillery and M-87 Orkan rockets.[22]

Second stage: 12–13 September

The second stage of the offensive commenced on 12 September. Its objective was the capture of Šipovo and Jajce by OG North after it successfully breached the VRS defences north of Glamoč. As the 7th Motorised Brigade of the VRS was forced to withdraw from positions near Vitorog in order to defend Šipovo, the rapid advance of the HV and the HVO meant the VRS could not consolidate a defensive line. On the same day, the HV deployed three Mil Mi-24 helicopter gunship sorties against VRS armour and artillery, and the HVO 1st Guards Brigade was able to reach Šipovo and capture the town. Its advance was also supported by the 1st HGZ, which advanced to outflank the VRS near Šipovo.[22] The assault was also supported by the 60th Guards Battalion, the General Staff Reconnaissance Sabotage Company,[26] heavy artillery and multiple rocket launchers. As the VRS positions around Šipovo began to give way, the 2nd Guards Brigade advanced against Jajce, reaching a point within 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) south of the town by the end of the day.[22] Its advance was supported by the 22nd Sabotage Detachment and the special police.[27]

On 13 September, as the 2nd Guards Brigade was approaching Jajce, the VRS withdrew from Donji Vakuf to avoid being surrounded, and the ARBiH captured the town. The 5th Corps of the ARBiH, on the left flank of the HV and HVO offensive, began its assault against the VRS 2nd Krajina Corps, moving south from Bihać towards Bosanski Petrovac.[25] The HV 81st Guards Battalion was inserted into the operation to support the HVO exploitation forces, and when it approached Mrkonjić Grad it clashed with the VRS 7th Motorised Brigade defending the town.[21] By the end of the day the 2nd Guards Brigade had reached Jajce.[22] The civilian population of Jajce was evacuated when its capture appeared imminent.[28] The 2nd Guards Brigade entered the deserted town,[29] recapturing the townwhich had been lost to the VRS in Operation Vrbas '92, nearly three years before.[22] Its capture prevented the 7th Corps of the ARBiH from advancing any further as its frontline facing the VRS all but disappeared. The 7th Corps then detached a substantial part of its force and sent them as reinforcements to the 5th Corps.[25]

Third stage: 14–15 September

The third stage of the operation centred on the capture of Drvar, the secondary objective of the overall offensive.[22] VRS defences around the town held until 14 September, when Gotovina detached a reinforced battalion from the 7th Guards Brigade held in the reserve of OG North and deployed it against Drvar. A renewed push by OGs West and South, combined with a rapid advance by the ARBiH 5th Corps against Bosanski Petrovac threatened to isolate Drvar, and the VRS withdrew from the town.[22]

The ARBiH 5th Corps captured Kulen Vakuf on 14 September, and Bosanski Petrovac the next day. It linked up with HV forces at the Oštrelj Pass, 12 kilometres (7.5 miles) southeast of the town on the road to Drvar.[25] The link-up was not smooth, as a friendly fire incident occurred, resulting in casualties.[30]

Aftermath

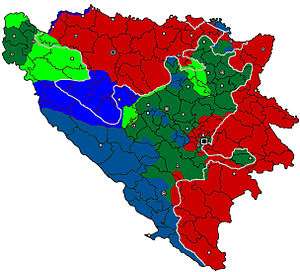

by HV and HVO, and by ARBiH

The combined HV and HVO force penetrated VRS defences by up to 30 kilometres (19 miles) capturing 2,500 square kilometres (970 square miles),[22] and demonstrating the improved skill of HV planners.[17] More significantly, Operation Mistral 2, as well as Operation Sana, as the first in a string of offensives launched shortly before the end of the Bosnian War, were crucial in applying pressure on the Bosnian Serbs. They also set the stage for further HV and HVO advances in Operation Southern Move.[31]

The Central Intelligence Agency analysed the effects of Operation Deliberate Force and Operations Maestral 2 and Sana, and noted that the NATO air campaign did not degrade VRS combat capability as much as was expected, because the airstrikes were never primarily directed at field-deployed units but at command and control infrastructure. This analysis noted that, while the NATO air campaign did degrade VRS capabilities, the final offensives by the HV, HVO and the ARBiH did the most damage.[32] The analysis further concluded that the ground offensives, rather than the NATO bombardment, were responsible for bringing the Bosnian Serbs to the negotiation table and the war to its end.[33] However, author Robert C. Owen argues that the HV would not have advanced as rapidly as it did had NATO not intervened and hampered the VRS defence by denying it long-range communications.[34]

Operation Mistral 2, along with the near-concurrent Operation Sana, created a large number of refugees from the areas previously controlled by the VRS. Their number was variously reported and the estimates range from 655 killed civilians and 125,000 refugees, reported by Radio-Television Republika Srpska in 2010,[35] to approximately 40,000 refugees reported in 1995—both by Bosnian Serb sources. The latter figure was reported to encompass the entire contemporary populations of the towns of Jajce, Šipovo, Mrkonjić Grad and Donji Vakuf fleeing or being evacuated.[36] At the time, the UN spokesman in Sarajevo estimated the number of refugees at 20,000.[28] The refugees fled to VRS-controlled areas around Brčko and Banja Luka,[29] adding to the 50,000 refugees who had been sheltering in Banja Luka since Operation Storm.[37]

During the Trial of Gotovina et al before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, Reynaud Theunens compared Operations Mistral 2 and Storm in his capacity as an expert witness for the prosecution. Theunens pointed out that civilian property and infrastructure at less risk in the aftermath of Operation Mistral 2, as Gotovina had issued much more strict orders in that respect, establishing companies specifically tasked with security and imposing a curfew in Jajce.[38] The HV and the HVO sustained losses of 74 killed and 226 wounded in the operation.[39]

In 2007, Croatian authorities received information that the commanding officer of the 7th Guards Brigade, Brigadier Ivan Korade, had ordered the killing of VRS prisoners of war during the offensive.[40] Charges of war crimes were brought against seven soldiers of the brigade, specifying that they executed Korade's orders to kill one VRS prisoner and one unknown man in the village of Halapić near Glamoč, and four VRS prisoners in the village of Mlinište. Five defendants were convicted and the remaining two acquitted in October 2011. Two of them were sentenced to six years in prison, one of them to five years and the remaining two to two years' imprisonment.[41] Korade was never tried, as he committed suicide following a standoff with police officers who sought to apprehend him in relation to a quadruple murder committed in late March 2008.[42] In 2016, Bosnian Serb officials filed a criminal complaint against the Croatian Minister of Defence, Damir Krstičević, alleging that he had committed war crimes during the offensive.[43]

Footnotes

- Ramet 2006, p. 382.

- Ramet 2006, p. 427.

- Ramet 2006, p. 428.

- CIA 2002, p. 136.

- CIA 2002, p. 137.

- CIA 2002, pp. 143–144.

- Bellamy 10 October 1992.

- Burns 12 May 1992.

- Ramet 1995, pp. 407–408.

- CIA 2002, p. 299.

- CIA 2002, pp. 376–377.

- CIA 2002, p. 377.

- CIA 2002, p. 378.

- Ripley 1999, p. 133.

- CIA 2002, p. 379.

- CIA 2002, p. 380.

- Ripley 1999, p. 200.

- Toal & Dahlman 2011, p. 133.

- CIA 2002, p. 418, n. 643.

- CIA 2002, p. 418, n. 644.

- CIA 2002, p. 419, n. 662.

- CIA 2002, p. 381.

- CIA 2002, p. 418, n. 649.

- CIA 2002, pp. 380–381.

- CIA 2002, p. 382.

- CIA 2002, p. 419, n. 659.

- CIA 2002, p. 419, n. 660.

- O'Connor 14 September 1995.

- Toal & Dahlman 2011, p. 134.

- O'Shea 2012, p. 170.

- CIA 2002, p. 391.

- CIA 2002, p. 395.

- CIA 2002, p. 396.

- Owen 2010, p. 219.

- RTRS 4 August 2010.

- Beelman 13 September 1995.

- Kennedy 14 September 1995.

- Slobodna Dalmacija 24 November 2008.

- Tuđman 15 January 1996.

- Toma 3 April 2008.

- CPNVHR 11 February 2014.

- NBC News 3 April 2008.

- Milekic 11 November 2016.

References

- Books

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 978-0-16-066472-4.

- O'Shea, Brendan (2012). Perception and Reality in the Modern Yugoslav Conflict: Myth, Falsehood and Deceit, 1991–1995. London, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-65024-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Owen, Robert C. (2010). A History of Air Warfare. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-59797-433-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (1995). Social Currents in Eastern Europe: The Sources and Consequences of the Great Transformation. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822315483.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918–2006. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ripley, Tim (1999). Operation Deliberate Force: The UN and NATO Campaign in Bosnia, 1995. Lancaster, England: Centre for Defence and International Security Studies. ISBN 978-0-9536650-0-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Toal, Gerard; Dahlman, Carl T. (2011). Bosnia Remade: Ethnic Cleansing and Its Reversal. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973036-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- News reports

- Beelman, Maud S. (13 September 1995). "Croats and Muslims Advance; Thousands More Refugees on the Move". Associated Press.

- Bellamy, Christopher (10 October 1992). "Croatia built 'web of contacts' to evade weapons embargo". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Burns, John F. (12 May 1992). "Pessimism Is Overshadowing Hope in Effort to End Yugoslav Fighting". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 November 2013.

- "Haag: Belgijanac uspoređivao "Maestral" i "Oluju"" [The Hague: The Belgian Compares Maestral and Storm]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). HINA. 24 November 2008.

- O'Connor, Mike (14 September 1995). "Bosnian Serb Civilians Flee Joint Muslim-Croat Attack". The New York Times.

- Kennedy, Helen (14 September 1995). "Serbs Flee Croat, Muslim Advance". Daily News.

- Milekic, Sven (11 November 2016). "Croatian Defence Minister Denies Bosnia War Crimes". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Shootout Kills Wanted Croatian General". NBC News. Associated Press. 3 April 2008.

- "Сјећање на жртве "Олује"" [Remembrance of the Victims of the "Storm"] (in Serbian). Radio Televizija Republike Srpske. 4 August 2010.

- Toma, Ivanka (3 April 2008). "Korade naredio ubojstvo pet srpskih zarobljenika" [Korade Ordered Murder of Five Serb Prisoners]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian).

- Other sources

- Tuđman, Franjo (15 January 1996). [Report of the President of the Republic of Croatia dr. Franjo Tuđman on State of the Croatian State and Nation in Year 1995/II – Croatian War of Independence, Liberation of Occupied Areas and Armed Forces] (in Croatian). Office of the President of Croatia – via Wikisource.

- "Zločin u Mliništu" [Crime in Mlinište] (in Croatian). Centre for Peace, Non-Violence and Human Rights. 11 February 2014.