Battle of Zadar

The Battle of Zadar (Croatian: Bitka za Zadar) was a military engagement between the Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija, or JNA), supported by the Croatian Serb Serbian Autonomous Oblast of Krajina (SAO Krajina), and the Croatian National Guard (Zbor Narodne Garde, or ZNG), supported by the Croatian Police. The battle was fought north and east of the city of Zadar, Croatia, in the second half of September and early October 1991 during the Croatian War of Independence. Although the JNA's initial orders were to lift the Croatian siege of the JNA's barracks in the city and isolate the region of Dalmatia from the rest of Croatia, the orders were amended during the battle to include capturing the Port of Zadar in the city centre. The JNA's advance was supported by the Yugoslav Air Force and Navy.

| Battle of Zadar | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence | |||||||||

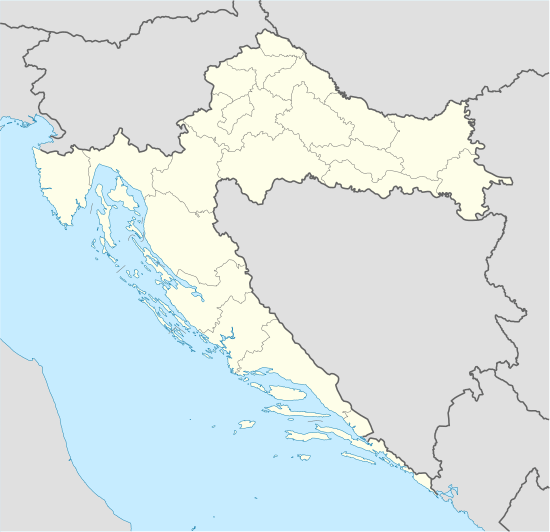

Zadar on the map of Croatia (JNA-held area in late December 1991 highlighted in red) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

3,000 (180th Brigade alone) |

4,500 (JNA estimate) | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| unknown | unknown | ||||||||

| 34 civilians killed in artillery bombardment of Zadar | |||||||||

Fighting stopped on 5 October, when a cease-fire agreement was reached by the belligerents after the JNA reached the outskirts of Zadar and blocked all land routes to the city. Subsequent negotiations resulted in a partial withdrawal of the JNA, restoring road access to Zadar via the Adriatic Highway and the evacuation of JNA facilities in the city. The JNA achieved a portion of its stated objectives; while it blocked the Maslenica Bridge (the last overland route between the Croatian capital of Zagreb and Zadar), a road via Pag Island (relying on a ferry) remained open. The JNA Zadar garrison was evacuated as a result of negotiations, but the ZNG captured several relatively small JNA posts in the city. The port was never captured by the JNA, although it was blockaded by the Yugoslav Navy.

The September–October fighting caused 34 civilian deaths in Zadar from the artillery bombardment. Croatia later charged 19 JNA officers involved in the offensive with war crimes against the civilian population; they were tried, convicted in absentia and sentenced to prison.

Background

After the 1990 electoral defeat of the government of the Socialist Republic of Croatia ethnic tensions between Croats and Croatian Serbs worsened, and the Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija, or JNA) confiscated Croatia's Territorial Defence (Teritorijalna obrana, or TO) weapons to minimize resistance.[1] On 17 August an open revolt broke out among the Croatian Serbs,[2] centred on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland near Knin[3] and parts of Lika, Kordun, Banovina and Slavonia.[4]

After two unsuccessful attempts by Serbia (supported by Montenegro and Serbia's provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo) to obtain the Yugoslav Presidency's approval for a JNA operation to disarm Croatian security forces in January 1991[5] and a bloodless skirmish between Serb insurgents and Croatian special police in March,[6] the JNA (supported by Serbia and its allies) asked the federal Presidency to give it wartime powers and declare a state of emergency. The request was denied on 15 March, and the JNA was brought under the control of Serbian President Slobodan Milošević. Milošević, preferring the expansion of Serbia to the preservation of Yugoslavia, threatened to replace the JNA with a Serbian army and declared that he no longer recognized the authority of the federal Presidency. The threat caused the JNA to gradually replace plans to preserve Yugoslavia with Serbian expansion.[7] By the end of March, the conflict escalated after the first fatalities during an incident at Plitvice Lakes.[8] The JNA stepped in, supporting the insurgents and preventing the Croatian police from intervening.[7] In early April, leaders of the Serb revolt in Croatia declared their intention to integrate the area under their control with Serbia; this was seen by the Government of Croatia as an intention to secede from Croatia.[9]

At the beginning of 1991, Croatia had no regular army; to bolster its defence, the country doubled its police personnel to about 20,000. The most effective portion of the force was the 3,000-strong special police, deployed in 12 battalions with a military structure; an additional 9,000–10,000 regionally organized reserve police were grouped into 16 battalions and 10 independent companies. Although most were equipped with small arms, a portion of the force was unarmed.[10] In May the Croatian government responded by forming the Croatian National Guard (Zbor narodne garde, or ZNG),[11] but its development was hampered by a United Nations (UN) arms embargo introduced in September.[12]

Prelude

In April and early May, ethnic tensions in Zadar and northern Dalmatia escalated after increased sabotage activities targeting communications, the power distribution grid and other property.[13] On 2 May, the situation continued to deteriorate after the killings of Croatian policemen at Borovo Selo and Franko Lisica (a member of the Croatian special police) in the village of Polača (near Zadar) by Serbian Autonomous Oblast of Krajina (SAO Krajina) troops. The news incited riots in Zadar that day, with crowds marching through the city centre demanding weapons to confront the Croatian Serbs and smashing the windows of shops owned by Serbian companies and Serbs living in the city.[14] Croat-owned businesses in Knin were destroyed in retaliation during the night of 7–8 May.[15] The JNA took an active role in events in nearby Benkovac on 19 May, distributing a leaflet with the names of 41 Croats targeted for immediate execution[16] and providing weapons to SAO Krajina forces in the area.[17] In late May, the conflict gradually escalated to exchanges of mortar fire.[18]

From late June through July, northern Dalmatia saw daily armed skirmishes but no actual combat; nonetheless, the conflict's increasing intensity in the region (and elsewhere in Croatia) caused residents of Zadar to build bomb shelters.[19] SAO Krajina authorities called up three TO units in the Zadar hinterland on 11 July (a day after the fatal shooting of a Croatian police patrol in the Zadar area),[20] and at the end of July the JNA 9th (Knin) Corps began conscripting the Serb population in Benkovac to strengthen its ranks.[21] On 1 August, Croatia deployed two battalions of the ZNG 4th Guards Brigade to Kruševo (near Obrovac); they were involved in combat with the SAO Krajina TO and police forces two days later, the first engagement of the Croatian War of Independence in the region.[22] Growing appetites of the SAO Krajina were announced in mid-August, when Milan Martić, one of its leaders, spoke of a planned conquest of Zadar.[23] Later that month, the JNA openly sided with the SAO Krajina. On 26 August the 9th (Knin) Corps troops and artillery (commanded by chief of staff Colonel Ratko Mladić) attacked the village of Kijevo, advancing with SAO Krajina forces to expel all Croats from the village.[24] Another regional setback for Croatia was the 11 September JNA capture of the Maslenica Bridge, cutting the last overland road link between Dalmatia and the rest of Croatia.[25]

On 14 September the ZNG and Croatian police blockaded and cut utilities to all accessible JNA facilities, beginning the Battle of the Barracks.[26] The move affected 33 large JNA garrisons in Croatia[27] and a number of smaller facilities (including border posts and weapons- and ammunition-storage depots),[26] forcing the JNA to change its plans for the Croatian campaign.[28]

Timeline

September

The planned JNA campaign included an advance in the Zadar area by the 9th (Knin) Corps. The corps began its operations against the ZNG on 16 September; fully mobilised and prepared for deployment, it was tasked with isolating Dalmatia from the rest of Croatia.[29] To achieve this, its units advanced with its main axis directed at Vodice and supporting advances directed towards Zadar, Drniš and Sinj. The initial push was intended to create conditions favouring attacks on Zadar, Šibenik and Split.[30] The bulk of the JNA 221st Mechanised Brigade, with its battalion of World War II-vintage T-34 tanks replaced by a battalion of M-84 tanks from the corps reserve, was committed to the main axis of the attack and supported by elements of the SAO Krajina TO. The secondary advance (towards Biograd na Moru) was assigned to the 180th Mechanised Brigade (supported by the T-34 battalion detached from the 221st Brigade), the 557th Mixed Antitank Artillery Regiment and elements of the SAO Krajina TO. Further elements of the 221st Brigade were detached from the main axis and tasked with lifting the ZNG blockade of JNA garrisons in the Sinj and Drniš areas. The overall offensive was supported by the 9th Mixed Artillery Regiment and the 9th Military Police Battalion.[31] Despite its initial secondary role, the 3,000-strong 180th Brigade became the main attacking force deployed against Zadar.[32] The city was defended by elements of the 4th Guards Brigade, the 112th Infantry Brigade, the independent Benkovac–Stankovci and Škabrnja battalions of the ZNG and the police.[33][34][35] Although the JNA estimated Croatian troop strength at approximately 4,500,[36] the Croatian units were poorly armed.[37] The city's defence was commanded by Colonel Josip Tuličić, head of the Zadar Sector of the 6th (Split) Operational Zone.[38]

The offensive began at 16:00 on 16 September; by the second day, JNA 9th (Knin) Corps commanding officer Major General Vladimir Vuković modified the initial plan because of significant resistance from the ZNG and Croatian police (who relied on populated areas and terrain features to hold back the JNA). Vuković's changes involved diverting part of the force to attack Drniš and Sinj, resting the remainder of the attacking force.[39] These orders were confirmed on 18 September by the JNA Military-Maritime District commander, Vice Admiral Mile Kandić.[40] The Yugoslav Navy began a blockade of the Croatian Adriatic coast on 17 September,[30] further isolating Zadar, and the city's electricity supply was cut on the first day of the JNA attack.[33] The ZNG was driven out of Polača, towards Škabrnja, on 18 September.[41] Croatian forces captured seven JNA facilities in Zadar,[33] the most significant the Turske kuće barracks and depot. The captures provided the ZNG with about 2,500 rifles, 100 M-53 machine guns[41] and ammunition, although the Yugoslav Air Force bombed the barracks on 22 September in an unsuccessful attempt to hinder removal of the weapons. The captured weapons bolstered the Croatian defence, but JNA attacks north of the city resulted in a stalemate; Croatian forces were spread too thin to defend the city and capture the remaining barracks, and the besieged JNA garrisons were too weak to break out.[30]

After this there was a lull in fighting in the Zadar area until the end of the month, with only sporadic small-arms fire and minor skirmishes.[42] During that period, the JNA's efforts were concentrated on the Battle of Šibenik and an advance towards Sinj. Although the ZNG defended Šibenik and Sinj it lost Drniš, abandoning it before the JNA's arrival on 23 September. During the last week of September the JNA returned its focus to Zadar, stepping up its artillery bombardment of the city and ending its naval blockade on 23 September.[30] On 29 September the JNA edged towards Zadar, capturing the villages of Bulić, Lišane Ostrovičke and Vukšić[41] and announcing its intention to evacuate its Zadar barracks (which was affected by desertions).[43]

October

The fighting picked up again on 2 October,[44] when a JNA tank-and-infantry attack on Nadin—the northernmost point of ZNG resistance in the Zadar area—was repelled.[45] On 3 October, the Yugoslav Navy reinstated its Adriatic blockade.[46] That day, the JNA 9th (Knin) Corps ordered a new push towards Zadar to relieve the city's JNA barracks, destroy the ZNG (or drive it from the city) and capture the Port of Zadar in the city centre. The attacking force was augmented by the 1st Battalion of the 592nd Mechanised Brigade.[47] The offensive began at 13:00 on 4 October, supported by artillery, naval and air forces.[30] The besieged JNA garrisons in the city, except for the Šepurine barracks garrison, also provided mortar and sniper support. The 271st Light Artillery Regiment and the 60th Medium Self-Propelled Missile Regiment of the Yugoslav Air Defence, based in Šepurine, broke through the Croatian siege and joined the advancing JNA force. Although the ZNG and the police held the city and inflicted many casualties, by the night of 4–5 October Zadar was besieged by the JNA; this forced the Croatian authorities to request a cease-fire and negotiations.[48]

The cease-fire was agreed at 16:00 on 5 October, and scheduled to begin two hours later; negotiations were set for 09:00 the following day. However, the fighting continued; negotiations did not take place as originally planned, with the JNA citing the Croatian general mobilization as the reason for their cancellation. Two days of negotiations then began at Zadar Airbase on 7 October. The talks involved Zadar JNA commander Vuković, Colonel Trpko Zdravkovski and Colonel Momčilo Perišić. Major Krešo Jakovina represented the General Staff of the HV at the talks, with Tuličić representing the regional defence command. With additional input from Zadar civilian representatives Ivo Livljanić and Domagoj Kero,[49] the cease-fire went into effect at noon on 10 October.[50] On 8 October, during the negotiations, Croatia declared its independence from SFR Yugoslavia.[51]

Aftermath

The JNA 9th (Knin) Corps had completed a significant part of its assigned task before the overall offensive against Croatian forces began in the second half of September by capturing the Maslenica Bridge, which blocked the Adriatic Highway and almost-completely isolated Dalmatia from the rest of Croatia.[52] This isolation was reinforced by the Yugoslav Navy blockade, which lasted until 13 October.[46] However, the cease-fire agreement ended the JNA siege and a supply route to Zadar was opened via the Pag Island road. The JNA remained on the outskirts of the city, threatening the ZNG defences.[53] Although the ZNG and the police could not withstand the JNA forces (supported by artillery and armour),[52] they held Zadar;[48] the city celebrates its defence on 6 October each year.[54]

The cease-fire agreement also provided for the evacuation of the JNA Zadar garrison. The evacuation, encompassing six barracks and 3,750 people,[55] began on 11 October and took 15 days to complete. The JNA removed 2,190–2,250 truckloads of weapons and equipment and the personal effects of JNA personnel and their families. Evacuated personnel and equipment were required to be removed from Croatian soil; the JNA complied, except for its artillery (which was primarily left for the SAO Krajina TO).[56] The JNA also transferred 20 truckloads of weapons to the SAO Krajina TO in the area.[57] On 18 October, the ZNG Independent Benkovac–Staknovci Battalion merged with the 1st Battalion of the 112th Brigade to create the 134th Infantry Brigade.[34]

The exact number of casualties sustained by the ZNG, the police or the JNA has never been reported; in Zadar, 34 civilians were killed and 120 structures damaged by artillery fire during September and October 1991. A group of 19 JNA officers, including Perišić and Mladić, were tried in absentia and convicted by a Croatian court for war crimes against the civilian population.[58][59]

Renewed fighting

After the JNA completed its evacuation of the Zadar garrison, its force north of the city regrouped and launched a new offensive on 18 November with infantry and armoured units (supported by artillery bombardment and close air support). The attack targeted the villages of Škabrnja, Gorica, Nadin and Zemunik Donji. Škabrnja was captured on the first day[60] after an air assault by a battalion of the JNA 63rd Parachute Brigade,[32] and Nadin fell on 19 November.[60] During and immediately after the attack on Škabrnja, the JNA and the supporting SAO Krajina TO forces killed 39 civilians and 14 ZNG soldiers in what became known as the Škabrnja massacre. Some of those killed were buried in a mass grave in the village; twenty-seven victims were exhumed in 1995, after the end of the war. Another seven civilians were killed in Nadin.[61]

On 21 November the JNA and the SAO Krajina TO destroyed the Maslenica Bridge[62] and began reorienting their main effort towards Novigrad, Pridraga, Paljuv and Podgradina, on the right flank of the Zadar sector.[60] Those efforts culminated on 31 December 1991 – 1 January 1992, when the four settlements were captured. On 3 January the JNA attacked Poličnik and Zemunik Donji, again threatening the road to Pag and Zadar; however, the advances failed.[63][64] Zadar was bombarded by artillery during the offensive.[60] A plan by the JNA 9th (Knin) Corps to advance to the Adriatic coast at Pirovac (east of Zadar) was drawn up by 30 December 1991 under the codename Strike 91 (Udar 91), but was not implemented.[65] This period saw more war crimes committed by SAO Krajina troops, including the killing of nine civilians and a JNA member in the Bruška massacre on 21 December.[66] Fighting stopped again on 3 January when a new cease-fire, based on a peace plan brokered by United Nations Special Envoy Cyrus Vance, went into effect.[67]

In early 1992, the Independent Škabrnja Battalion became the 1st Battalion of the 159th Infantry Brigade.[35] Control of the battlefield changed slightly during the night of 22–23 May 1992, when Croatian forces captured Križ Hill (near Bibinje, southeast of Zadar); this improved security along the Adriatic Highway.[68] Another change took place in January–February 1993, when Croatian troops recaptured part of the Zadar hinterland in Operation Maslenica.[69] The rest of the region was recaptured by Croatia during Operation Storm in August 1995.[70]

Footnotes

- Hoare 2010, p. 117.

- Hoare 2010, p. 118.

- The New York Times & 19 August 1990.

- Woodward 1995, p. 170.

- Hoare 2010, pp. 118–119.

- Ramet 2006, pp. 384–385.

- Hoare 2010, p. 119.

- The New York Times & 3 March 1991.

- The New York Times & 2 April 1991.

- CIA 2002, p. 86.

- EECIS 1999, pp. 272–278.

- The Independent & 10 October 1992.

- Ružić 2011, p. 409.

- Ružić 2011, p. 410.

- Ružić 2011, p. 412.

- Ružić 2011, pp. 412–413.

- Ružić 2011, p. 414.

- Ružić 2011, p. 413.

- Ružić 2011, p. 416.

- Ružić 2011, p. 418.

- Ružić 2011, p. 420.

- Ružić 2011, p. 421.

- The New York Times & 20 August 1991.

- Silber & Little 1996, pp. 171–173.

- CIA 2002, p. 93.

- CIA 2002, p. 95.

- Ramet 2006, p. 401.

- CIA 2002, p. 96.

- CIA 2002, p. 99.

- Brigović 2011, p. 428.

- Hrvatski vojnik & September 2010.

- Brigović & Radoš 2011, p. 9.

- Zadarski list & 23 September 2011.

- Čerina 2008, p. 422.

- 057info & 28 August 2011.

- Hrvatski vojnik & October 2010d.

- Čerina 2008, p. 420.

- tportal.hr & 18 November 2011.

- Hrvatski vojnik & October 2010a.

- Hrvatski vojnik & October 2010b.

- Čerina 2008, p. 421.

- Hrvatski vojnik & October 2010c.

- Los Angeles Times & 29 September 1991.

- 057info & 20 November 2011.

- Brigović & Radoš 2011, p. 11.

- Brigović 2011, pp. 428–429.

- Hrvatski vojnik & November 2010.

- Brigović 2011, p. 429.

- Brigović 2011, pp. 429–430.

- Brigović 2011, p. 430.

- Brigović & Radoš 2011, p. 5.

- CIA 2002, p. 103.

- Brigović 2011, p. 432.

- Nacional & 6 October 2007.

- Brigović 2011, p. 431.

- Brigović 2011, p. 433.

- Brigović 2011, pp. 431–432.

- Novi list & 1 March 2013.

- DORH & 14 March 2007.

- Brigović & Radoš 2011, p. 10.

- Brigović & Radoš 2011, p. 14.

- Thomas & Mikulan 2006, p. 53.

- Brigović 2011, p. 450.

- Zadarski list & 3 January 2013.

- Zadarski list & 21 November 2011.

- ICTY & 12 June 2007, p. 147.

- Armatta 2010, pp. 194–196.

- 057info & 16 April 2009.

- CIA 2002, pp. 267–268.

- CIA 2002, pp. 367–377.

References

- Books

- Armatta, Judith (2010). Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosevic. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4746-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. OCLC 50396958.

- Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. London, England: Routledge. 1999. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–136. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918–2006. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silber, Laura; Little, Allan (1996). The Death of Yugoslavia. London, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-026168-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas, Nigel; Mikulan, Krunislav (2006). The Yugoslav Wars (1): Slovenia & Croatia 1991–95. Oxford, England: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-963-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woodward, Susan L. (1995). Balkan Tragedy: Chaos and Dissolution after the Cold War. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 9780815722953.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scientific journal articles

- Brigović, Ivan; Radoš, Ivan (May 2011). "Zločin Jugoslavenske narodne armije i srpskih postrojbi nad Hrvatima u Škabrnji i Nadinu 18.-19. studenoga 1991. godine" [The Crime Committed Against Croats by the Yugoslav People's Army (YPA) and Serb Units in Škabrnja and Nadin on November 18–19, 1991]. Croatology (in Croatian). University of Zagreb Center for Croatian Studies. 1 (2): 1–23. ISSN 1847-8050.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brigović, Ivan (October 2011). "Odlazak Jugoslavenske narodne armije s područja Zadra, Šibenika i Splita krajem 1991. i početkom 1992. godine" [Departure of the Yugoslav People's Army from the area of Zadar, Šibenik and Split in late 1991 and early 1992]. Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian). Croatian Institute of History. 43 (2): 415–452. ISSN 0590-9597.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Čerina, Josip (July 2008). "Branitelji benkovačkog kraja u Domovinskom ratu" [Defenders of the Benkovac area in the Croatian War of Independence]. Drustvena Istrazivanja: Journal for General Social Issues (in Croatian). Institute of Social Sciences Ivo Pilar. 17 (3): 415–435. ISSN 1330-0288.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ružić, Slaven (December 2011). "Razvoj hrvatsko-srpskih odnosa na prostoru Benkovca, Obrovca i Zadra u predvečerje rata (ožujak - kolovoz 1991. godine)" [The Development of the Croatian-Serbian Relations in Benkovac, Obrovac and Zadar on the Eve of War (March-August 1991)]. Journal - Institute of Croatian History (in Croatian). Institute of Croatian History, Faculty of Philosophy Zagreb. 43 (1): 399–425. ISSN 0353-295X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- News reports

- "Memorijalni centar "Brdo Križ"" [Križ Hill Memorial Centre] (in Croatian). 057info. 16 April 2009. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- "Nadin ponosan na svoje žrtve" [Nadin is proud of its victims] (in Croatian). 057info. 20 November 2011. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- "Samostalnom škabrnjskom bataljunu prvo državno odličje" [Independent Škabrnja Battalion receives the first national decoration] (in Croatian). 057info. 28 August 2011. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- Bellamy, Christopher (10 October 1992). "Croatia built 'web of contacts' to evade weapons embargo". The Independent. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- Brkić, Velimir (3 January 2013). "Prvi poraz srpskih snaga u Domovinskom ratu" [The first defeat of the Serb forces in the Croatian War of Independence]. Zadarski list (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- Engelberg, Stephen (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- Klarica, Siniša (23 September 2011). "Zauzimanjem vojarni spriječen pakleni plan JNA da u Zadar uđu tenkovskim snagama" [Capture of the barracks foiled JNA's deadly plan to enter Zadar with tanks]. Zadarski list (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- "Yugoslavia: Army Leaves More Towns in Croatia". Los Angeles Times. 29 September 1991. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- "Perišić već 14 godina na tjeralici zbog granatiranja Zadra" [Perišić wanted for 14 years for Zadar shelling]. Novi list (in Croatian). HINA. 1 March 2013. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 April 1991). "Rebel Serbs Complicate Rift on Yugoslav Unity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (20 August 1991). "Truce in Croatia on Edge of Collapse". The New York Times.

- Šurina, Maja (18 November 2011). "Masakr u Škabrnji mogao se spriječiti?" [Škabrnja massacre was avoidable?] (in Croatian). tportal.hr. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- "Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts". The New York Times. Reuters. 19 August 1990. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- Vidović, Ante (21 November 2011). "O stankovačkoj bojni napisat će se knjiga" [A book will be written on the Stankovci Battalion]. Zadarski list (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- Zrinjski, Marijana (6 October 2007). "Zadar obilježava Dan obrane" [Zadar makes the Day of the defence]. Nacional (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 2013-11-28. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- Other sources

- Nazor, Ante (September 2010). "Dokumenti o napadnim operacijama JNA i pobunjenih Srba u Dalmaciji 1991. (I. DIO)" [Documents on offensive operations of the JNA and the rebel Serbs in Dalmatia in 1991 (Part 1)]. Hrvatski vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (311). ISSN 1333-9036. Archived from the original on 2013-11-30. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- Nazor, Ante (October 2010). "Dokumenti o napadnim operacijama JNA i pobunjenih Srba u Dalmaciji 1991. (II. DIO)" [Documents on offensive operations of the JNA and the rebel Serbs in Dalmatia in 1991 (Part 2)]. Hrvatski Vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (312). ISSN 1333-9036. Archived from the original on 2013-11-30. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- Nazor, Ante (October 2010). "Dokumenti o napadnim operacijama JNA i pobunjenih Srba u Dalmaciji 1991. (III. DIO)" [Documents on offensive operations of the JNA and the rebel Serbs in Dalmatia in 1991 (Part 3)]. Hrvatski Vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (313). ISSN 1333-9036. Archived from the original on 2013-11-30. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- Nazor, Ante (October 2010). "Dokumenti o napadnim operacijama JNA i pobunjenih Srba u Dalmaciji 1991. (V. DIO)" [Documents on offensive operations of the JNA and the rebel Serbs in Dalmatia in 1991 (Part 5)]. Hrvatski Vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (315). ISSN 1333-9036. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013.

- Nazor, Ante (October 2010). "Dokumenti o napadnim operacijama JNA i pobunjenih Srba u Dalmaciji 1991. (VI. DIO)" [Documents on offensive operations of the JNA and the rebel Serbs in Dalmatia in 1991 (Part 6)]. Hrvatski Vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (316). ISSN 1333-9036. Archived from the original on 2013-11-30. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- Nazor, Ante (November 2010). "Dokumenti o napadnim operacijama JNA i pobunjenih Srba u Dalmaciji 1991. (VII. DIO)" [Documents on offensive operations of the JNA and the rebel Serbs in Dalmatia in 1991 (Part 7)]. Hrvatski Vojnik (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia) (317). ISSN 1333-9036. Archived from the original on 2013-11-30. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- "Priopćenje povodom napisa u medijima" [A communique in response to media reports] (in Croatian). State Attorney's Office of Croatia. 14 March 2007. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013.

- "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic – Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 12 June 2007.