Battle of the Miljevci Plateau

The Battle of the Miljevci Plateau was a clash of the Croatian Army (Hrvatska vojska - HV) and forces of the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK), fought on 21–23 June 1992, during the Croatian War of Independence. The battle represented the culmination of a series of skirmishes between the HV and the RSK forces in Northern Dalmatia, after the implementation of the Vance plan and deployment of the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) began. The skirmishes occurred in the pink zones—areas under control of the RSK, but outside the UN Protected Areas established by the Vance plan.

| Battle of the Miljevci Plateau | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence | |||||||

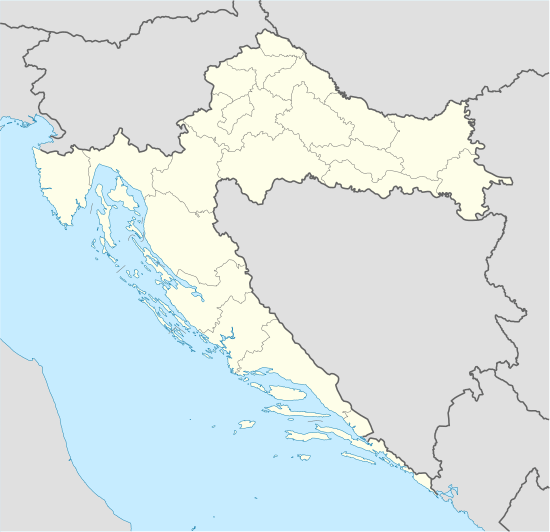

Miljevci Plateau on the map of Croatia. RSK- or JNA-held areas in early 1992 are highlighted red. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

113th Brigade 142nd Brigade | 1st Brigade | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 250 | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7–8 killed |

40 killed, 17 captured 10 tanks and APCs destroyed 6 howitzers captured | ||||||

Elements of two HV brigades advanced several kilometres north of Šibenik and captured the Miljevci Plateau, encompassing 108 square kilometres (42 square miles) of territory and seven villages. After the battle, the UNPROFOR requested the HV to pull back to its positions prior to 21 June, and the request was followed by the United Nations Security Council Resolution 762 urging Croatia to withdraw from the plateau, but the HV remained in place. In the immediate aftermath, Croatian authorities claimed the offensive was not ordered by the General Staff and that the advance was made in response to a series of provocations. After the battle, some bodies of the killed RSK soldiers were thrown into a karst pit and were not retrieved until August, when the released prisoners of war informed the UNPROFOR of the location of the bodies.

Background

In 1990, following the electoral defeat of the government of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, ethnic tensions worsened. The Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija – JNA) confiscated Croatia's Territorial Defence Force's (Teritorijalna obrana – TO) weapons to minimize resistance.[1] On 17 August, the tensions escalated into an open revolt by Croatian Serbs,[2] centred on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around Knin,[3] parts of the Lika, Kordun, Banovina regions and eastern Croatia.[4]

Following the Pakrac clash between Serb insurgents and Croatian special police in March 1991,[5] the conflict had escalated into the Croatian War of Independence.[6] The JNA stepped in, increasingly supporting the Croatian Serb insurgents.[7] In early April, the leaders of the Croatian Serb revolt declared their intention to integrate the area under their control, known as SAO Krajina, with Serbia.[8] In May, the Croatian government responded by forming the Croatian National Guard (Zbor narodne garde – ZNG),[9] but its development was hampered by a United Nations (UN) arms embargo introduced in September.[10]

On 8 October, Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia,[11] and a month later the ZNG was renamed the Croatian Army (Hrvatska vojska – HV).[9] Late 1991 saw the fiercest fighting of the war, as the 1991 Yugoslav campaign in Croatia culminated in the Siege of Dubrovnik,[12] and the Battle of Vukovar.[13] In November, Croatia, Serbia and the JNA agreed upon the Vance plan, contained in the Geneva Accord. The plan entailed a ceasefire, protection of civilians in specific areas designated as United Nations Protected Areas and UN peacekeepers in Croatia.[14] The ceasefire came into effect on 3 January 1992.[15] In December 1991, the European Community announced its decision to grant a diplomatic recognition to Croatia on 15 January 1992.[16] SAO Krajina renamed itself the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) on 19 December 1991.[17]

Despite the Geneva Accord requiring an immediate withdrawal of JNA personnel and equipment from Croatia, the JNA stayed behind for up to eight months in some areas. When its troops eventually pulled out, JNA left their equipment to the RSK.[18] As a consequence of organisational problems and breaches of ceasefire, the UN peacekeepers, named the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR), did not start to deploy until 8 March.[19] The UNPROFOR took two months to fully assemble in the UN Protected Areas (UNPAs). Furthermore, the RSK forces remained in areas outside designated UNPAs which were under RSK control at the time of the signing of the Implementation Agreement ceasefire of 3 January 1992. Those areas, later better known as the pink zones,[20] were supposed to be restored to Croatian control from the outset of the plan implementation.[21] Failure of this aspect of the implementation of the Vance plan made the pink zones a major source of contention for Croatia and the RSK.[22]

Prelude

Before the UNPROFOR fully deployed, the HV clashed with an armed force of the RSK in the village of Nos Kalik, located in a pink zone near Šibenik, and captured the village at 4:45 p.m. on 2 March 1992. The JNA formed a battlegroup to counterattack the next day.[23] The JNA battlegroup, augmented by elements of the 9th Military Police Battalion, deployed at 5:50 a.m. and clashed with the HV force in Nos Kalik.[24] However, the JNA counterattack failed.[25] The HV captured 21 RSK troops in Nos Kalik, intent on exchanging the prisoners for Croats held under arrest in Knin.[26] Following negotiations, the HV agreed to pull back on 11 April, but later declined to do so, claiming deteriorating security at the battlefield in general prevented the withdrawal.[27] Several Serb-owned houses in Nos Kalik were torched after the HV captured the village.[28]

The HV clashed with units subordinated to the 180th Motorised Brigade of the JNA in a pink zone near Zadar on 17–22 May. While the JNA repelled attacks in most areas around Zadar and Stankovci, the HV managed to cut a JNA base at the Križ Hill away from the rest of the force on 17 May.[29] The JNA outpost occupied high ground overlooking the surrounding area, including Zadar. It housed radar equipment and was used as an artillery observer post.[30] The JNA attempted to relieve the besieged garrison in the next few days, however the attempts failed and the base surrendered to the HV on 22 May.[29] The attack and capture of the Križ Hill, codenamed Operation Jaguar, was carried out by the 2nd Battalion of the 159th Infantry Brigade of the HV, supported by artillery of the 112th Infantry Brigade.[30]

Timeline

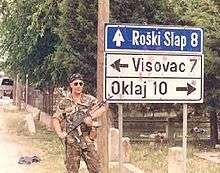

On 21 June, the HV attacked RSK positions at the Miljevci Plateau, located in the pink zone north of Šibenik.[31] The TO forces in the area were subordinated to the 1st Brigade of the TO,[32] and Lieutenant Colonel General Milan Torbica.[33] The HV deployed 250 troops, elements of the 113th and 142nd Infantry Brigades, commanded by Brigadier Kruno Mazalin. The HV had infiltrated the pink zone along three routes—via Nos Kalik, across the Čikola river and by boat sailing upstream along the Krka River, during the night of 20/21 June. The fighting began at 5 a.m. as the HV force, deployed in 26 squads, captured six out of seven villages on the plateau by the end of the morning. At 8:00 p.m., the HV captured the village of Ključ, and all of the plateau.[34] The advance created a HV-held salient south of Knin, several kilometres deep. It also led the RSK artillery to bombard Šibenik and HV bombardment of Knin in response, both on 22 June.[31]

The artillery fire progressively intensified until 23 June, while the RSK mobilised and counterattacked against the HV positions at the Miljevci Plateau.[31] However, the mobilisation yielded only 227 additional troops,[35] and the counterattack failed.[36] An UNPROFOR assessment concluded the situation might deteriorate further and engulf all of the pink zones. To address the situation, UNPROFOR military commander Lieutenant General Satish Nambiar met with Deputy Prime Minister of Croatia Milan Ramljak and Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Croatia General Anton Tus in Zagreb the same day, in order to discuss the developments on the Miljevci Plateau.[31] Skirmishes continued on 24 June, accompanied by some artillery fire. Morale of the RSK troops plummeted though, causing a TO garrison based in nearby Trbounj to abandon its barracks.[35]

Aftermath

According to Croatian sources, the HV lost seven or eight troops killed in the battle.[34][37] Serb sources cite 40 killed RSK troops,[38] in the battle or its immediate aftermath, while the HV took seventeen prisoners.[39] The prisoners were taken to the Kuline barracks in Šibenik. On 23 June, a total of 29 RSK soldiers killed at the Miljevci Plateau on the first day of the battle were thrown into the Bačića Pit, contrary to orders given by Brigadier Ivan Bačić, commanding officer of the 113th Infantry Brigade. Bačić ordered burial of the killed RSK troops at a local Serbian Orthodox cemetery. The same day, one prisoner, Miroslav Subotić, was shot in Nos Kalik by HV personnel.[40] He was one of a group of prisoners tasked with clearance of the area after the fighting.[41] The HV also destroyed ten tanks and armoured personnel carriers, and captured six howitzers and a considerable stockpile of other weapons and ammunition in the battle.[36] The offensive brought seven villages and 108 square kilometres (42 square miles) to HV control.[37]

During their meeting with Nambiar, Ramljak and Tus claimed that the offensive was neither planned nor ordered by authorities in Zagreb. They stated that the advance was made in response to a series of provocations made by the RSK armed forces.[31] Bačić claimed that while no specific order to attack was received, Tus did instruct him to respond aggressively and capture as much territory as possible in cases of grave breaches of ceasefire by the RSK forces. Nevertheless, Bačić was reprimanded by the President of Croatia Franjo Tuđman because of the offensive.[36] In the RSK, Torbica was forced to resign his post and was replaced by Major General Mile Novaković.[42]

UNPROFOR and the European Community Monitor Mission (ECMM) requested the HV to withdraw to positions held before the offensive, but the HV declined the request. However, Croatia agreed that UNPROFOR and ECMM monitors would continue to be present in the pink zones when Croatia assumed control over them. The move was planned as a way to reassure the Serb population that the pink zones could provide them safety.[31] In the aftermath of the offensive, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) adopted the UNSC Resolution 762, urging cessation of hostilities in or near the UNPAs, and urging the HV to pull back to positions held before 21 June.[43] The 113th Brigade of the HV remained at the plateau regardless.[44] The resolution authorised the UNPROFOR to perform monitoring of the pink zones. It also recommended establishment of a joint commission chaired by an UNPROFOR representative, and including representatives of the Government of Croatia, local authorities and the ECMM to oversee restoration of Croatian control in the pink zones.[21]

The prisoners taken by the HV were released in August, and they informed the UNPROFOR about the bodies in the Bačića Pit and the death of Subotić.[40] The bodies were retrieved by Croatian authorities in the presence of UNPROFOR and other international organisations.[45] Two Croatian military police members were charged with Subotić's murder in 2011. As of 2013 the trial is ongoing.[41]

In 2012, twenty years after the battle, President Ivo Josipović presented the Charter of the Republic of Croatia to the commanders and units involved in the battle, commending their military achievements. That was the first such move in twenty years, and a reversal of the official stance towards the offensive which had originally declared it as an unauthorised deployment of the HV.[34]

Footnotes

- Hoare 2010, p. 117.

- Hoare 2010, p. 118.

- The New York Times & 19 August 1990.

- ICTY & 12 June 2007.

- Ramet 2006, pp. 384–385.

- The New York Times & 3 March 1991.

- Hoare 2010, p. 119.

- The New York Times & 2 April 1991.

- EECIS 1999, pp. 272–278.

- The Independent & 10 October 1992.

- Narodne novine & 8 October 1991.

- Bjelajac & Žunec 2009, pp. 249–250.

- The New York Times & 18 November 1991.

- Armatta 2010, pp. 194–196.

- Marijan 2012, p. 103.

- The New York Times & 24 December 1991.

- Ahrens 2007, p. 110.

- Armatta 2010, p. 197.

- Trbovich 2008, p. 300.

- CIA 2002, pp. 106–107.

- UN & September 1996.

- Nambiar 2001, p. 172.

- Rupić 2008, pp. 266–267.

- Rupić 2008, p. 272.

- Rupić 2008, pp. 274–276.

- Rupić 2008, p. 277.

- Rupić 2008, p. 386.

- Rupić 2008, p. 294.

- Rupić 2008, pp. 509–510.

- Zadarski list & 6 October 2012.

- Bethlehem & Weller 1997, p. 527.

- Sekulić 2000, p. 270.

- Rupić 2008, p. 560.

- Radio Drniš & 21 June 2012.

- Rupić 2008, p. 561.

- Slobodna Dalmacija & 21–22 June 1999.

- MORH & 21 June 2012.

- Blic & 21 June 2012.

- Rupić 2009, p. 127.

- Slobodna Dalmacija & 26 October 2001.

- CFNVHR.

- Sekulić 2000, pp. 123–124.

- UNSC & 30 June 1992.

- Marijan 2007, p. 68.

- Slobodna Dalmacija & 4 February 2001.

References

- Books

- Ahrens, Geert-Hinrich (2007). Diplomacy on the Edge: Containment of Ethnic Conflict and the Minorities Working Group of the Conferences on Yugoslavia. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8557-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Armatta, Judith (2010). Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosevic. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4746-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bethlehem, Daniel L.; Weller, Marc, eds. (1997). "25. Further Report of the Secretary-General Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 752 (1992) (S/24188, 26 June 1992)". The 'Yugoslav' Crisis in International Law: General Issues, Volume 1. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 526–529. ISBN 978-0-521-46304-1.

- Bjelajac, Mile; Žunec, Ozren (2009). "The War in Croatia, 1991–1995". In Charles W. Ingrao; Thomas Allan Emmert (eds.). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-533-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. OCLC 50396958.

- Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. London, England: Routledge. 1999. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marijan, Davor (2007). Oluja [Storm] (PDF) (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Memorial Documentation Centre of the Homeland War of the Government of Croatia. ISBN 978-953-7439-08-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-31. Retrieved 2014-01-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nambiar, Satish (2001). "UN peacekeeping operations in the former Yugoslavia - from UNPROFOR to Kosovo". In Thakur, Ramesh; Schnabel, Albrecht (eds.). United Nations peacekeeping operations: ad hoc missions, permanent engagement. United Nations University Press. ISBN 978-92-808-1067-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918–2006. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rupić, Mate, ed. (2008). Republika Hrvatska i Domovinski rat 1990.-1995. - Dokumenti, Knjiga 3 [The Republic of Croatia and the Croatian War of Independence 1990-1995 - Documents, Volume 3] (PDF) (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: Hrvatski memorijalno-dokumentacijski centar Domovinskog rata. ISBN 978-953-7439-13-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-11. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- Rupić, Mate, ed. (2009). Republika Hrvatska i Domovinski rat 1990.-1995. - Dokumenti, Knjiga 5 [The Republic of Croatia and the Croatian War of Independence 1990-1995 - Documents, Volume 5] (PDF) (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: Hrvatski memorijalno-dokumentacijski centar Domovinskog rata. ISBN 978-953-7439-19-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-10. Retrieved 2014-01-05.

- Sekulić, Milisav (2000). Knin je pao u Beogradu [Knin was lost in Belgrade] (in Serbian). Bad Vilbel, Germany: Nidda Verlag. OCLC 47749339. Archived from the original on 2013-11-11. Retrieved 2017-09-08.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trbovich, Ana S. (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scientific journal articles

- Marijan, Davor (May 2012). "The Sarajevo Ceasefire – Realism or strategic error by the Croatian leadership?". Review of Croatian History. Croatian Institute of History. 7 (1): 103–123. ISSN 1845-4380.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- News reports

- Bellamy, Christopher (10 October 1992). "Croatia built 'web of contacts' to evade weapons embargo". The Independent.

- Blažević, Davorka (21–22 June 1999). "Miljevačka se akcija može uspoređivati s masleničkom" [Miljevci Operation Compares to Maslenica]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian).

- Blažević, Davorka (4 February 2001). "Haag (još) ne pita za Kuline niti za Miljevce" [The Hague not (yet) Interested in Kuline or Miljevci]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian).

- Blažević, Davorka (26 October 2001). "Tražim azil u Haagu" [Asylum Sought in the Hague]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian).

- Engelberg, Stephen (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times.

- Jelčić Stojaković, Matilda (21 June 2012). "Svečano obilježena 20. obljetnica oslobođenja Miljevaca" [The 20th Anniversary of Liberation of Miljevci Celebrated] (in Croatian). Radio Drniš. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- Kinzer, Stephen (24 December 1991). "Slovenia and Croatia Get Bonn's Nod". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012.

- Klarica, Siniša (6 October 2012). "Agotić nam nije rekao ni "hvala"" [Agotić Did Not Even Thank Us]. Zadarski list (in Croatian).

- "Parstos ubijenim Srbima na Miljevačkom platou" [Service for Killed Serbs at the Miljevci Plateau]. Blic (in Serbian). 21 June 2012.

- "Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts". The New York Times. Reuters. 19 August 1990.

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 April 1991). "Rebel Serbs Complicate Rift on Yugoslav Unity". The New York Times.

- Sudetic, Chuck (18 November 1991). "Croats Concede Danube Town's Loss". The New York Times.

- Other sources

- "Anniversary of Miljevci liberation". Ministry of Defence (Croatia). HINA. 21 June 2012.

- "Crime at Miljevci Plateau". Centre for Peace, Non-Violence and Human Rights. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013.

- "Odluka" [Decision]. Narodne novine (in Croatian). Narodne novine (53). 8 October 1991. ISSN 1333-9273. Archived from the original on 2009-09-23.

- "Resolution 762 (1992) Adopted by the Security Council at its 3088th meeting, on 30 June 1992". United Nations Security Council. 30 June 1992.

- "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic - Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 12 June 2007.

- "United Nations Protection Force". Department of Public Information, United Nations. September 1996.