Christmas Uprising

The Christmas Uprising or Christmas Rebellion (Serbian: Божићна побуна, Božićna pobuna) was a failed uprising in Montenegro led by the Greens in early January 1919. The military leader of the uprising was Krsto Zrnov Popović and its political leader was Jovan S. Plamenac.

| Christmas Uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

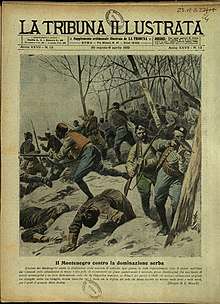

Cover of the Italian weekly La Tribuna Illustrata from 1919, titled "Montenegro against Serbian domination" (Italian: Il Montenegro contro la dominazione serba) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Estimates vary from 1,500[1] to 5,000[2] | Estimates vary from 500[3] to 4,000[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 98 killed and wounded | 30 killed[5] | ||||||

The catalyst for the uprising was the decision of the controversial Grand People's Assembly in Montenegro, commonly known as the Podgorica Assembly, to unify the Kingdom of Montenegro unconditionally with the Kingdom of Serbia, which would immediately after form the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Following a questionable candidate selection process, the unionist Whites outnumbered the Greens, who favored preserving Montenegrin statehood and unification into a confederal Yugoslavia.

The uprising reached a climax in Cetinje on 7 January 1919, the date of Orthodox Christmas. The unionists, with support from the Serbian Army, defeated the rebel Greens. In the aftermath of the uprising, the dethroned King Nicholas I was forced to issue a call for peace, many homes were destroyed and a number of participants in the uprising were tried and imprisoned. Some of the rebels fled to the Kingdom of Italy, while others retreated to the mountains, continuing a guerrilla resistance under the banner of the Montenegrin Army in Exile which lasted until 1929, most notably the militia of Savo Raspopović (hr).

Background

Multiple historians acknowledge that a majority of Montenegrins supported the unification with other Southern Slavs on a federal basis after the World War I.[6][2] However, support for unification did not involve the same degree of support for the Podgorica Assembly, since many of those who supported unification wanted Montenegro to join the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes as an autonomous entity, ultimately in a confederation rather than a centralized Serbian kingdom.[2]

Plan

The plan of the Greens consisted of six points.[7]

- Vojvoda Đuro Petrović, leading several rebel battalions, was to take the town of Nikšić. From there, they were to march through Čevo and Cuce to Cetinje, in unison with rebels from Njeguši.

- General Milutin Vučinić, leading troops from Piperi, Lješkopolje and Zeta, was to attack Podgorica and move towards Cetinje, crossing through Lješanska nahija. His troops were to meet up with the troops of vojvoda Đuro Petrović between Čevo and Lješanska nahija.

- Jovan Plamenac, leading troops from Crmnica, and with the support of detachments from Ljubotinj, was to head towards Cetinje. The three groups were to attack Cetinje simultaneously to disarm the Serbian troops there, and terminate them in case of resistance. In the case of a victory, the plan was to transport captured Serbians to the island of Lesendro in Lake Skadar. Rebels were instructed to carry food for three days, and the government in exile in Neuilly-sur-Seine was requested to provide food for 15,000 people for twenty days, a uniform for those currently without one, rifles, machine guns, ammunition and several cannons. They were to send the food and equipment to a place near Lake Skadar.

- When the entirety of Montenegro is freed, the government in exile would begin sending food more regularly to the civilian population.

- Expecting a counter-attack from the Vasojevići and Serbians, the government in exile was requested to facilitate the creation of bands of Albanian fighters which would attack them between Peć and Plav. For this reason, the government in exile was to supply Jovan Plamenac with 1.200.000 francs.

- The government in exile was to inform the world of the public opinion in Montenegro.[7]

This plan was delivered to Antonio Baldacci on 14 December 1918.[7]

Rebellion

Fighting around Podgorica

The rebellion first broke out around Podgorica. Some Martinići headed by commanders Stevan and Bogić Radović took control of Spuž Fortress. The Piperi headed by Brigadier General Milutin Vučinić severed the road between Danilovgrad and Podgorica at Vranićke Njive. Commander Andrija and Captain Mato Raičević seized Velje Brdo overlooking Podgorica.[8]

Since most Bjelopavlići were supporters of the unification, the rebels who occupied Spuž Fortress were quickly forced to capitulate with no bullets fired. The leaders were detained and their troops were sent home. The Bjelopavlići, for the most part consisting of the youth, continued toward Podgorica. They were met at Vranićke Njive by Vučinić, where fighting would have probably broken out, had the youth of Podgorica, Piperi and Kuči not simultaneously reached his troops from behind. Vučinić was surrounded, and ordered his troops to lay down their arms. The leaders were, again, detained and transported to Podgorica, and the troops sent home. The same happened at Velje Brdo.[8]

The defeat at Podgorica would prove to be a strong setback for the rebels, since the troops that were disarmed were supposed to help with the sieges of Nikšić and Cetinje. Also, the rebels seemed less united and less willing, which had its toll on the confidence of the Greens in other areas.[8]

Fighting around Nikšić

The town of Nikšić was surrounded on 3 January 1919 [O.S. 21 December 1918] but no fighting broke out until the afternoon of 5 January. The siege was led from one side by Major Šćepan Mijušković, a veteran of several previous wars. During the morning, the rebels delivered an ultimatum to the town's defenders to send their commanders to the new brewery by the Bistrica river. Shots were fired first from Trebjesa hill, and after from Čađelica, Glavica and from around the brewery.[9]

The town's youth organized a council where Dr Niko Martinović was elected president, and Marko Kavaja, later screenwriter, secretary. Some veterans also joined, however the troops in the town under the command of Captain Stojić lost contact with Cetinje and stood down. Stojić armed the youth with one machine gun. Kavaja went to negotiate with the rebels in Pandurica, in the company of a POW, the brother of Radojica Nikčević, one of the rebel leaders. He claims that the rebels were not opposed to the unification, but were fighting for their "honorable vojvodas and serdars". The negotiations failed to stop the fighting.[9]

At sunset, the siege was relieved by Bjelopavlići forces. After hearing that more reinforcements from Grahovo were coming to the aid of the defenders, many rebels deserted. The Drobnjaci arrived late to the defense, being sidetracked by bad weather. After the fighting had ended, several rebel leaders were captured including Đuro and Marko Petrović, and former Defense Minister Marko Đukanović. Misja Nikolić and Brigadier General Đuro Jovović escaped, having went into hiding and crossed into Italy, respectively.[9]

Siege of Virpazar

Unrest started around the Crmnica town of Virpazar on 3 January 1919 [O.S. 21 December 1918], where the supporters of King Nicholas were led by Jovan Plamenac.[10]

According to Commander Jagoš Drašković, Plamenac approached Virpazar in the morning of 3 January with over 400 men, while Drašković defended the town with around 350. The number of defenders increased during the day, and Plamenac hoped to reach the Italian troops further to the south for supplies and ammunition. Since Drašković placed his troops between Plamenac and the Italians, Plamenac agreed to meet with Drašković, who was accompanied by Dr Blažo Lekić, leader of the Crmnica youth and an older local, Stanko Đurović. Plamenac agreed to send his men home, in return for a letter guaranteeing his safe passage to Cetinje after his men disbanded.[10]

Drašković concludes that Plamenac agreed to disband his troops because he was unsure of his victory, and because his plan was to deal with Virpazar and Rijeka Crnojevića quickly, after which his troops in the area could join the siege of Cetinje, which was planned to be over by 5 January. Since this proved impossible, he counted on improving the Greens' odds with Cetinje by appearing in person and in the company of at least a few men.[10]

Plamenac disbanded most of his troops in the evening of 3 January, and proceeded to his native village of Boljevići with around 60 men, who planned to march on Cetinje the following day. On 4 January, Andrija Radović stopped in Virpazar while returning from Shkodër, where he held a speech in front of the Crmnica locals. He threatened Plamenac, and pointed out that he was now decorated with more foreign honors than the late Ilija Plamenac. Drašković considers this speech to have acted to the detriment of the White cause, primarily because it enraged the locals who held Ilija Plamenac in high regard. Because of this new situation, Jovan Plamenac started rallying his men again.[10]

In the evening of 4 January, Drašković marched on Boljevići with around 150 men, but Plamenac had already retreated toward Seoca and Krnjice. Drašković returned to Virpazar and boarded his men on a ship headed for Krnjice, where he attacked Plamenac and his troops. The Greens retreated into Skadarska Krajina, and crossed the Bojana to join the Italian troops in Albania.[10]

Fighting around Rijeka Crnojevića

Though a minor hamlet, Rijeka Crnojevića was central to the Greens' plan. After its fall, troops from the area were to launch a serious strike on Cetinje. The town was surrounded on 3 January 1919 [O.S. 21 December 1918] by troops under the command of Commander Đuro Šoć. The towns defenders were led by Brigade General Niko Pejanović and, though low in number, held their positions.[11]

The first day of the siege, Pejanović wrote to one of the Greens' commanders to call off the attack. Šoć wrote to the local command, the head of the srez and the president of the municipality. He requested that the defenders produce three hostages, evacuate all Serbian troops and provided that the defenders leave Rijeka Crnojevića armed, after which he guaranteed that they would be escorted to Shkodër with honor. He states in his letters that Montenegro had been "sold for Judas' silver" and that while being the "torch of Serb freedom", it was occupied by "brotherly Šumadijans who replaces the Austro-Hungarians". His claims that 35,000 Montenegrins were participating in the uprising and that Virpazar was already conquered were widely overstated.[11]

During the night, reinforcements arrived from Podgorica to lift the siege. According to Jovan Ćetković, member of the Podgorica Assembly, the youth of Podgorica met with the Greens during the night around Carev Laz near Rvaši. After a short verbal confrontation, leaders of the youth agreed to negotiate with the Greens in Rvaši. Todor Božović, Captain Jovan Vuksanović and Podgorica Assembly MP Nikola Kovačević–Mizara proceeded to Rvaši accompanied by 5-6 other members of the youth. The rest set up camp near Carev Laz and were led by Captain Radojica Damjanović and flag-bearer Nikola Dragović. There, they met Captains Đuza Đurašković and Marko Radunović who were waiting for a negotiator from the Greens. They waited in Rvaši until daybreak, when a group went toward Rijeka to the village of Drušići. They found serdar Joko Jovićević who summoned a local, Captain Đuko Kostić, and initiated negotiations between the two groups.[11]

In the morning of 4 January, while the groups were negotiating, the youth decided to push forward contrary to the command of Todor Božović. They met the Greens under the command of Captain Jovan Vujović in the village of Šinđon, near Rijeka Crnojevića, where the Greens held higher ground. The Greens realized that, while initially outnumbering the town's defenders, they were now outnumbered. They agreed to send their men home and salute to the Whites' flag, which was highly unpopular among the rebel troops.[11]

After breaking the siege of Rijeka Crnojevića, the Whites achieved an extremely significant victory and by 5 January, troops under the command of Serbian General Dragutin Milutinović had both ended a minor uprising in Rijeka Crnojevića and had stopped a larger attack on Nikšić.[11][12]

Siege of Cetinje

As Jovan Plamenac and the other rebel leaders had planned, Cetinje turned out to be the epicenter of the uprising. After several days of exchanging letters, the rebels began forming armed squads on 31 December [O.S. 18 December] 1918. The rebels gathered in front of the House of Government on 1 January 1919 and left town for the hills. Recruits were called to arms by ringing the church bells in the vicinity of Cetinje. By 2 January, Cetinje was surrounded from all sides.[13]

According to Ćetković, the town was, at this moment in time, defended by around 100 members of the national guard i.e 20–30 men each from several tribes around Cetinje, 50–60 members of the youth, 50 gendarmes and policemen and 100 members of the 2nd Yugoslav Regiment under Colonel Dragutin Milutinović. The troops were lacking in ammunition, and every defender had between 50 and 100 rounds. Milutinović's troops were armed with two cannons and around 1,000 shells.[13]

Youth leader Marko Daković requested that Milutinović deliver arms to his troops, but since he was himself lacking in arms and ammunition, he directed Daković toward the commander of the Second Army stationed in Sarajevo, vojvoda Stepa Stepanović. The telephone lines were still operational and Stepanović allowed Daković to restock from the army garrison in Tivat. During 2 January, leader of the Lješanska national guard Lieutenant Radoje Ćetković reached Tivat and returned with around 2,000 rifles and ample ammunition.[13]

The following day, on 3 January, a delegation headed by Brigade Generals Milutin Vukotić and Jovo Bećir went to negotiate with the rebel leaders at their headquarters in the village of Bajice. According to General Milutinović, the negotiations were unsuccessful and he went to negotiate personally around 2 P.M. Milutinović met Commander Đuro Drašković and Lieutenant Ilija Bećir, the latter of whom he describes as insolent for having said "Either the Serbians (Serbian: Србијанци) leave Montenegro or there will be blood, there isn't and there cannot be any other way". In his return, Milutinović met his troops who begged him to attack Bajice, but their request was denied because he "still hoped that everything would end peacefully".[13]

In the morning of 4 January, serdar Janko Vukotić arrived in Cetinje. He had broken through the rebels' advance guard with a force of 30 men from Čevo. Milutinović advised Vukotić to make arrangements with the National Executive Committee, to allow him to try negotiating with the rebels in Bajice. The Committee agreed, and Vukotić went to Bajice by car, accompanied with two captains and an MP of the Podgorica Assembly. The two captains returned on foot not long after with word that Vukotić and the MP had been captured. Other than the capture of serdar Vukotić and some gendarmes encountering a minor roadblock on their way to the villages of Kosijeri and Jabuka, no fighting took place on that day.[13]

On 5 January, a list of requests written by Krsto Popović a day earlier was delivered to Milutinović, asking for the termination of resolutions by the Podgorica Assembly. Milutinović replied to him the next day, alleging that he was responsible for his troops in Montenegro, but also promised to bring Popović's requests to the government in Belgrade.[12]

On 6 January 1919, around 250 Serbian troops and 850 volunteers from nearby Montenegrin tribes fought a formation of approximately 1,500 to 2,000 rebel Greens in Cetinje.[12] That day, the Greens initiated a siege on Cetinje, killing some members of the Great National Assembly and killing some Whites. After that, the Greens experienced severe factionalism, in addition to facing the militarily stronger Whites.[14]

International influence and reactions

Italian role

As a result of the Podgorica Assembly, King Nicholas was exiled to the Kingdom of Italy, from which the uprising enjoyed substantial support. King Nicholas's Ministers asked for the Italian Expedition Corps in Albania to enter Montenegro, "in order for it to be liberated solely by Italian troops".[15] A committee organized by Italian ethnographer Antonio Baldacci supported the Greens until at least 1921.[16]

In late November 1918 during the Podgorica Assembly, Italian troops attempted to take control of the coastal areas of Montenegro under the guise of Entente troop movement, but got prevented from doing so.

International response

In the spring of 1919, the United States sent Charles W. Furlong as an envoy from the Peace Commission to Montenegro. Furlong reported to The New York Times in an interview published on June 15, 1919, that the electors in the Podgorica Assembly acted as carpetbaggers did in the United States.[17]

An initiative called the Inter-Allied Commission of Investigation monitored the Podgorica Assembly and the Whites after the uprising. It included Louis Franchet d'Espèrey, as well as lieutenants from the United States, United Kingdom, and Italy. They recorded that there were as few as 500 unionist troops in Montenegro, and that they were not exclusively Serbian but from other constituents of the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. The commission also concluded from interviewing Greens held as prisoners that the uprising had been "caused by agents of King Nicholas I and supported by some emissaries from Italy."[3]

Aftermath

Later in the twentieth century, the Christmas Uprising was subject to ideological emphasis in Montenegrin nationalism. In World War II, one of the earliest leaders of the Greens, Sekula Drljević, invited the Italian occupation of Montenegro and collaborated with the Independent State of Croatia in order to break away from Yugoslavia.

Since Montenegro declared independence from Serbia in 2006, the Christmas Uprising has been memorialized on polar opposite ends of the Montenegrin historical conscious. In 1941, a memorial on the burial site of unionist Whites was destroyed by the Italian occupation of Montenegro in Cetinje.[5] As of 2017, a walkway was paved on the same burial site in Cetinje without any recognition to the Whites.[5] On 7 January 2008, on the 90th anniversary of the uprising, Montenegrin Prime Minister Milo Đukanović revealed a memorial statue for the Greens who were killed in the insurrection.[6]

References

- Pavlović, Srđa (2008). Balkan Anschluss: The Annexation of Montenegro and the Creation of the Common South Slavic State. p. 166.

- Novak Adžić (January 6, 2018). "Portal Analitika: Božićni ustanak crnogorskog naroda 1919. godine (I)" (in Serbian). Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Woodhouse & Woodhouse 1920, p. 111.

- Andrijašević 2015, p. 262.

- Novica Đurić (March 20, 2017). "Politika: Šetalište skriva grobnicu branilaca ujedinjenja sa Srbijom" (in Serbian).

- Predrag Tomović (January 7, 2010). "Radio Slobodna Evropa: Božićni ustanak izaziva kontroverze na 90. godišnjicu" (in Serbian). Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Kordić 1986, pp. 44-45.

- Kordić 1986, pp. 49-50.

- Kordić 1986, pp. 51-54.

- Kordić 1986, pp. 55-57.

- Kordić 1986, pp. 59-64.

- Andrijašević 2015, p. 261.

- Kordić 1986, pp. 65-84.

- Morrison 2009, p. 44.

- Živojinović, Dragoljub: Pitanje Crne Gore i mirovna konferencija 1919 [The Issue of Montenegro and the 1919 Peace Conference], Belgrade 1992, p. 7. See Rastoder, Šerbo: Crna Gora u egzilu [Montenegro in Exile], Podgorica 2004.

- Srđan Rudić, Antonello Biagini (2015). Serbian-Italian Relations: History and Modern Times : Collection of Works. p. 146.

- Woodhouse & Woodhouse 1920, p. 110.

Sources

- Andrijašević, Živko (2015). Istorija Crne Gore. Belgrade: Atlas fondacija, Vukotić media. ISBN 978-86-89613-35-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kordić, Mile (1986). Crnogorska buna 1919-1924 (in Serbian). Belgrade: Nova knjiga.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morrison, Kenneth (2009). Montenegro: A Modern History. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1845117107.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woodhouse, Edward James; Woodhouse, Chase Going (1920). Italy and the Jugoslavs. Boston: Richard G. Badger, The Gorham Press. Retrieved 24 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "Serbs Wipe out Royalist Party in Montenegro". The Chicago Daily Tribune (Vol. LXXVIII, No. 212). Chicago, IL. 4 September 1919. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010.