Bulgarian–Serbian wars of 917–924

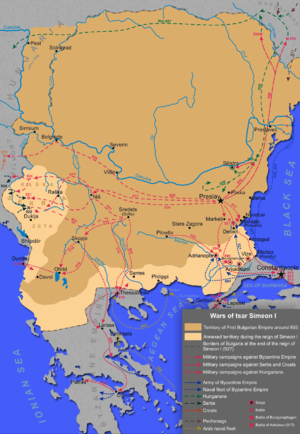

The Bulgarian–Serbian wars of 917–924 (Bulgarian: Българо–сръбски войни от 917–924) were a series of conflicts fought between the Bulgarian Empire and the Principality of Serbia as a part of the greater Byzantine–Bulgarian war of 913–927.[1][2] After the Byzantine army was annihilated by the Bulgarians in the battle of Achelous, the Byzantine diplomacy incited the Principality of Serbia to attack Bulgaria from the west. The Bulgarians dealt with that threat and replaced the Serbian prince with a protégé of their own. In the following years the two empires competed for control over Serbia. In 924 the Serbs rose again, ambushed and defeated a small Bulgarian army. That turn of events provoked a major retaliatory campaign that ended with the annexation of Serbia in the end of the same year.

| Bulgarian–Serbian wars of 917–924 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Bulgarian–Serbian wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Bulgarian Empire |

Principality of Serbia Byzantine Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Simeon I the Great Theodore Sigritsa Marmais |

Petar Gojniković Pavle Branović Zaharija Pribisavljević | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

Prelude

Soon after Simeon I (r. 893–927) ascended to the throne, he successfully defended Bulgaria's commercial interests, acquired territory between the Black Sea and the Strandzha mountains, and imposed an annual tribute on the Byzantine Empire as a result of the Byzantine–Bulgarian war of 894–896.[3][4] The outcome of the war confirmed the Bulgarian domination on the Balkans but also exposed the country's vulnerability to foreign intervention under the influence of the Byzantine diplomacy.[a][5] As soon as the peace with Byzantium had been signed, Simeon I sought to secure the Bulgarian positions in the western Balkans. After the death of prince Mutimir (r. 850–891), several members of the ruling dynasty fought for the throne of the Principality of Serbia.[6] In 892 Petar Gojniković established himself as a prince. In 897 Simeon I agreed to recognize Petar and put him under his protection, resulting in a twenty-year period of peace and stability to the west.[6] However, Petar was not content with his subordinate position and sought ways to achieve independence.[6]

After almost two decades of peace between Bulgaria and the Byzantine Empire, the Byzantine emperor Alexander (r. 912–913) provoked a conflict with Bulgaria in 913. Simeon I, who was seeking pretext to confront the Byzantines to claim an imperial title for himself, took the opportunity to wage war.[7][8] Unlike his predecessors, Simeon I's ultimate ambition was to assume the throne of Constantinople as a Roman emperor, creating a joint Bulgarian–Roman state.[9] Later that year he forced the Byzantines to recognize him as Emperor of the Bulgarians (in Bulgarian, Tsar)[10][11] and to betroth his daughter to the under-age emperor Constantine VII, which would have paved his way to become father-in-law and guardian of the emperor.[12][13][14] However, after a coup d'état in February 914 the new Byzantine government under Constantine VII's mother Zoe Karbonopsina revoked the concessions and the hostilities continued.[14] On 20 August 917 the Byzantines suffered a devastating defeat at the hands of the Bulgarian army in the Battle of Achelous which de facto brought the Balkans under Bulgarian control.[15][16] Weeks later, another Byzantine host was heavily defeated in the battle of Katasyrtai just outside Constantinople in a night combat.[17][18]

Wars

Shortly before the Battle of Achelous the Byzantines had tried to create a wide anti-Bulgarian coalition. As part of their efforts the strategos of Dyrrachium Leo Rhabdouchos was instructed to negotiate with the Serbian prince Petar Gojniković, who was a Bulgarian vassal. Petar Gojniković responded positively but the court in Preslav was warned about the negotiations by prince Michael of Zahumlje, a loyal ally of Bulgaria, and Simeon I was able to prevent an immediate Serb attack.[17][19][20]

Following the victories in 917 the way to Constantinople lay open but Simeon I decided to deal with prince Petar Gojniković before advancing further against the Byzantines. An army was dispatched under the command of Theodore Sigritsa and Marmais. The two persuaded Petar Gojniković to meet them, seized him and sent his to capital Preslav, where he died in prison.[17][21][22] The Bulgarians replaced Petar with Pavle Branović, a grandson of prince Mutimir, who had long lived in Preslav. Thus, Serbia was turned into a puppet state until 921.[17]

In an attempt to bring Serbia under their control, in 920 the Byzantines sent Zaharija Pribislavljević, another of Mutimir's grandsons, to challenge the rule of Pavle. Zaharija was either captured by the Bulgarians en route[21] or by Pavle,[23] who had him duly delivered to Simeon I. In either way, Zaharija ended up in Preslav. Despite the setback, the Byzantines persisted and eventually bribed Pavle to switch sides after lashing much gold on him.[24] In response, in 921 Simeon I sent a Bulgarian army headed by Zaharija. The Bulgarian intervention was successful, Pavle was easily deposed and once again a Bulgarian candidate was placed on the Serbian throne.[24][25]

The Bulgarian control did not last long, because Zaharija was raised in Constantinople where he was heavily influenced by the Byzantines.[24] Soon Zaharija openly declared his loyalty to the Byzantine Empire and commenced hostilities against Bulgaria. In 923[24][26] or in 924[25] Simeon I sent a small army led by Thedore Sigritsa and Marmais but they were ambushed and killed. Zaharija sent their heads and armour to Constantinople.[24][27] This action provoked a major retaliatory campaign in 924. A large Bulgarian force was dispatched, accompanied by a new candidate, Časlav, who was born in Preslav to a Bulgarian mother.[26][27] The Bulgarians ravaged the countryside and forced Zaharija to flee to the Kingdom of Croatia.

This time, however, the Bulgarians had decided to change the approach towards the Serbs. They summoned all Serbian župans to pay homage to Časlav, had them arrested and taken to Preslav.[26][27] Serbia was annexed as a Bulgarian province, expanding the country's border to Croatia, which at the time had reached its apogee and proved to be a dangerous neighbour.[28] The annexation was a necessary move since the Serbs had proved to be unreliable allies[28] and Simeon I had grown wary of the inevitable pattern of war, bribery and defection.[29] According to Constantine VII's book De Administrando Imperio Simeon I resettled the whole population to the interior of Bulgaria and those who avoided captivity fled to Croatia, leaving the country deserted.[29]

Aftermath

The Bulgarian advance in the Western Balkans were checked by the Croats who defeated a Bulgarian army in 926. Similarly to the case of Serbia, Croatia was invaded in the context of the Byzantine–Bulgarian conflict, because king Tomislav (r. 910–928) was a Byzantine ally and harboured enemies of Bulgaria.[30] After the death of Simeon I on 27 May 927 his son and successor Peter I (r. 927–969) concluded a favourable peace treaty with the Byzantines, securing recognition of the Imperial title of the Bulgarian rulers, an independent Bulgarian Patriarchate and an annual tribute.[31]

Despite this diplomatic success and the end of the 14-year-long conflict, the beginning of Peter I's reign was plagued by internal instability. The young monarch faced two consecutive revolts by his brothers Ivan and Michael.[32][33] The Serbian prince Časlav took advantage Peter I's internal problems. In 928 or 931 he managed to escape from Preslav and to assert Serbia's independence from Bulgaria under Byzantine overlordship.[32][34] With Byzantine financial and diplomatic support he managed to repopulate and reorganize the country.[29][34]

See also

|

Footnotes

Notes

^ a: During the War of 894–896 the Byzantines incited the Magyars to attack Bulgaria. The Magyars defeated the Bulgarian army twice and plundered the north-eastern regions of the country as far as the capital Preslav before they were eventually defeated by the Bulgarians.[5]

Citations

- Ćirković 2004, pp. 18.

- Curta 2006, pp. 212.

- Fine 1991, pp. 139-149.

- Zlatarski 1972, pp. 318–321

- Whittow 1996, p. 287

- Fine 1991, pp. 141.

- Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 97

- Fine 1991, pp. 143.

- Fine 1991, pp. 144.

- Fine 1991, pp. 145-148.

- Whittow 1996, p. 289

- Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 98

- Fine 1991, pp. 145.

- Gregory 2005, p. 228

- Andreev & Lalkov 1996, pp. 99–100

- Angelov & co 1981, pp. 287–288

- Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 256

- Angelov & co 1981, pp. 288–289

- Angelov & co 1981, pp. 286

- Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 99

- Fine 1991, pp. 150.

- Stephenson 2004, pp. 26–27

- Angelov & co 1981, p. 290

- Fine 1991, pp. 152.

- Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 101

- Angelov & co 1981, p. 291

- Bozhilov & Gyuzelev 1999, p. 259

- Fine 1991, pp. 154.

- Stephenson 2004, p. 27

- Fine 1991, pp. 157.

- Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 108

- Andreev & Lalkov 1996, p. 109

- Fine 1991, pp. 162-163.

- Fine 1991, pp. 159.

Sources

- Primary sources

- Moravcsik, Gyula, ed. (1967) [1949]. Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (2nd revised ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Secondary sources

- Андреев (Andreev), Йордан (Jordan); Лалков (Lalkov), Милчо (Milcho) (1996). Българските ханове и царе [The Bulgarian Khans and Tsars] (in Bulgarian). Велико Търново (Veliko Tarnovo): Абагар (Abagar). ISBN 954-427-216-X.

- Ангелов (Angelov), Димитър (Dimitar); Божилов (Bozhilov), Иван (Ivan); Ваклинов (Vaklinov), Станчо (Stancho); Гюзелев (Gyuzelev), Васил (Vasil); Куев (Kuev), Кую (Kuyu); Петров (Petrov), Петър (Petar); Примов (Primov), Борислав (Borislav); Тъпкова (Tapkova), Василка (Vasilka); Цанокова (Tsankova), Геновева (Genoveva) (1981). История на България. Том II. Първа българска държава [History of Bulgaria. Volume II. First Bulgarian State] (in Bulgarian). София (Sofia): Издателство на БАН (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Press).

- Бакалов (Bakalov), Георги (Georgi); Ангелов (Angelov), Петър (Petar); Павлов (Pavlov), Пламен (Plamen); Коев (Koev), Тотю (Totyu); Александров (Aleksandrov), Емил (Emil); и колектив (2003). История на българите от древността до края на XVI век [History of the Bulgarians from Antiquity to the end of the XVI century] (in Bulgarian). София (Sofia): Знание (Znanie). ISBN 954-621-186-9.

- Божилов (Bozhilov), Иван (Ivan); Гюзелев (Gyuzelev), Васил (Vasil) (1999). История на средновековна България VII–XIV век [History of Medieval Bulgaria VII–XIV centuries] (in Bulgarian). София (Sofia): Анубис (Anubis). ISBN 954-426-204-0.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gregory, Timothy E. (2005). A History of Byzantium. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23513-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kazhdan, A.; collective (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Runciman, Steven (1930). "The Two Eagles". A History of the First Bulgarian Empire. London: George Bell & Sons. OCLC 832687.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stephenson, Paul (2004). Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-03402-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whittow, Mark (1996). The Making of Byzantium (600–1025). Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20497-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Златарски (Zlatarski), Васил (Vasil) (1972) [1927]. История на българската държава през средните векове. Том I. История на Първото българско царство [History of the Bulgarian state in the Middle Ages. Volume I. History of the First Bulgarian Empire.] (in Bulgarian) (2 ed.). София (Sofia): Наука и изкуство (Nauka i izkustvo). OCLC 67080314.