Estazolam

Estazolam (brand name ProSom) is a benzodiazepine medication. It possesses anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, sedative and skeletal muscle relaxant properties. Estazolam is an intermediate-acting oral benzodiazepine. It is used for short-term treatment of insomnia.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | ProSom, Eurodin, Nuctalon, others |

| Other names | Desmethylalprazolam |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a691003 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 93% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 10–24 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.045.424 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

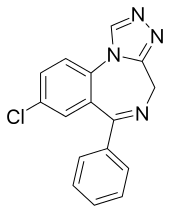

| Formula | C16H11ClN4 |

| Molar mass | 294.7 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

It was patented in 1968 and came into medical use in 1975.[1]

Medical uses

.jpg)

Estazolam is prescribed for the short-term treatment of certain sleep disorders. It is an effective hypnotic drug showing efficacy in increasing the time spent asleep as well as reducing awakenings during the night. Combination with non-pharmacological options for sleep management results in long-term improvements in sleep quality after discontinuation of short-term estazolam therapy.[2][3] Estazolam is also sometimes used as a preoperative sleep aid. It was found to be superior to triazolam in side effect profile in preoperative patients in a trial.[4] Estazolam also has anxiolytic properties and due to its long half life can be an effective short-term treatment for insomnia associated with anxiety.[5]

Side effects

A hang-over effect commonly occurs with next day impairments of mental and physical performance.[6] Other side effects of estazolam include somnolence, dizziness, hypokinesia, and abnormal coordination.[7]

Tolerance and dependence

The main safety concern of benzodiazepines such as estazolam is a benzodiazepine dependence and the subsequent benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome which can occur upon discontinuation of the estazolam. A review of the literature found that long-term use of benzodiazepines such as estazolam is associated with drug tolerance, drug dependence, rebound insomnia and CNS related adverse effects. Estazolam should only be used short term and at the lowest effective dose to avoid complications related to long-term use. Non-pharmacological treatment options however, were found to have sustained improvements in sleep quality.[8][9] The short-term benefits of benzodiazepines on sleep begin to reduce after a few days due to tolerance to the hypnotic effects of benzodiazepines in the elderly.[10]

Contraindications and special caution

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the elderly, during pregnancy, in children, alcohol or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[11]

Elderly

An extensive review of the medical literature regarding the management of insomnia and the elderly found that there is considerable evidence of the effectiveness and durability of non-drug treatments for insomnia in adults of all ages and that these interventions are underutilized. Compared with the benzodiazepines including estazolam, the nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotics appeared to offer few, if any, significant clinical advantages in efficacy or tolerability in elderly persons. It was found that newer agents with novel mechanisms of action and improved safety profiles, such as the melatonin agonists, hold promise for the management of chronic insomnia in elderly people. Long-term use of sedative-hypnotics for insomnia lacks an evidence base and has traditionally been discouraged for reasons that include concerns about such potential adverse drug effects as cognitive impairment (anterograde amnesia), daytime sedation, motor incoordination, and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents and falls. In addition, the effectiveness and safety of long-term use of these agents remain to be determined. It was concluded that more research is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of treatment and the most appropriate management strategy for elderly persons with chronic insomnia.[12]

Pharmacology

Estazolam is classed as a "triazolo" benzodiazepine drug.[13] Estazolam exerts its therapeutic effects via its benzodiazepines receptor agonist properties.[14] Estazolam at high doses decreases histamine turnover via its action at the benzodiazepine-GABA receptor complex in mouse brains.[15]

Pharmacokinetics

Peak plasma levels are achieved within 1–6 hours. Estazolam is an intermediate acting benzodiazepine. The elimination half life of estazolam is an average of 19 hours, with a range of 8–31 hours.[16][17] The major metabolite of estazolam is 4-hydroxyestazolam.[18]

Interactions

Alcohol enhances the sedative hypnotic properties of estazolam.[19] In package inserts, the manufacturer clearly warns about an interaction with Ritonavir, and although clinical interactions of Ritonavir with estazolam have not yet been described, the lack of clinical descriptions of the interactions does not negate the seriousness of the interaction. Do not combine estazolam with Ritonavir.[20]

EEG effects in rabbits

An animal study in rabbits demonstrated that estazolam induces a drowsy pattern of spontaneous EEG including high voltage slow waves and spindle bursts increase in the cortex and amygdala, while the hippocampal theta rhythm is desynchronized. Also low voltage fast waves occur particularly in the cortical EEG. The EEG arousal response to auditory stimulation and to electric stimulation of the mesencephalic reticular formation, posterior hypothalamus and centromedian thalamus is significantly suppressed. The photic driving response elicited by a flash light in the visual cortex is significantly suppressed by estazolam.[21]

Abuse

A primate study found that estazolam has abuse potential.[22] Estazolam is a drug with the potential for misuse. Two types of drug misuse can occur; recreational misuse, where the drug is taken to achieve a high or when the drug is continued long term against medical advice.[23] Estazolam became notorious in 1998 when a large amount of an 'herbal sleeping mix' called Sleeping Buddha was recalled from the shelves after the FDA discovered that it contained estazolam.[24] In 2007, a Canadian product called Sleepees was recalled after it was found to contain undeclared estazolam.[25][26]

See also

- Alprazolam

- Benzodiazepine

- Benzodiazepine dependence

- Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome

- Long-term effects of benzodiazepines

- Brotizolam

- Midazolam

- Triazolam

References

- Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 538. ISBN 9783527607495.

- Roehrs T, Zorick F, Lord N, Koshorek GL, Roth T (June 1983). "Dose-related effects of estazolam on sleep of patients with insomnia". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 3 (3): 152–6. doi:10.1097/00004714-198306000-00002. PMID 6135720.

- Rosen RC, Lewin DS, Goldberg L, Woolfolk RL (October 2000). "Psychophysiological insomnia: combined effects of pharmacotherapy and relaxation-based treatments". Sleep Med. 1 (4): 279–288. doi:10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00042-3. PMID 11040460.

- Mauro C, Sperlongano P (September 1987). "[Controlled clinical evaluation of 2 hypnotic triazole benzodiazepines, estazolam and triazolam, used the night before surgical interventions]". Minerva Med. (in Italian). 78 (18): 1381–4. PMID 2889169.

- Post GL; Patrick RO; Crowder JE; et al. (August 1991). "Estazolam treatment of insomnia in generalized anxiety disorder: a placebo-controlled study". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 11 (4): 249–53. doi:10.1097/00004714-199108000-00005. PMID 1918423.

- Müller KW, Müller-Limmroth W, Strasser H (1982). "[Alterations of sleep stage pattern in human beings and hang-over effects under the influence of estazolam/2nd Comm.: Studies on the hang-over effect in psycho-physiological performance (author's transl)]". Arzneimittelforschung (in German). 32 (4): 456–60. PMID 6125155.

- Pierce MW, Shu VS, Groves LJ (March 1990). "Safety of estazolam. The United States clinical experience". Am. J. Med. 88 (3A): 12S–17S. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(90)90280-Q. PMID 1968713.

- Kirkwood CK (1999). "Management of insomnia". J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 39 (5): 688–96, quiz 713–4. doi:10.1016/S1086-5802(15)30354-5. PMID 10533351.

- Lee YJ (2004). "Overview of the therapeutic management of insomnia with zolpidem". CNS Drugs. 18 Suppl 1: 17–23, discussion 41, 43–5. doi:10.2165/00023210-200418001-00005. PMID 15291010.

- Grad RM (November 1995). "Benzodiazepines for insomnia in community-dwelling elderly: a review of benefit and risk". J Fam Pract. 41 (5): 473–81. PMID 7595266.

- Authier, N.; Balayssac, D.; Sautereau, M.; Zangarelli, A.; Courty, P.; Somogyi, AA.; Vennat, B.; Llorca, PM.; Eschalier, A. (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Ann Pharm Fr. 67 (6): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- Bain KT (June 2006). "Management of chronic insomnia in elderly persons". Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 4 (2): 168–92. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.06.006. PMID 16860264.

- Braestrup C; Squires RF. (1 April 1978). "Pharmacological characterization of benzodiazepine receptors in the brain". Eur J Pharmacol. 48 (3): 263–70. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(78)90085-7. PMID 639854.

- Akbarzadeh T, Tabatabai SA, Khoshnoud MJ, Shafaghi B, Shafiee A (March 2003). "Design and synthesis of 4H-3-(2-phenoxy)phenyl-1,2,4-triazole derivatives as benzodiazepine receptor agonists". Bioorg. Med. Chem. 11 (5): 769–73. doi:10.1016/S0968-0896(02)00469-8. PMID 12538007.

- Oishi R; Nishibori M; Itoh Y; Saeki K. (May 27, 1986). "Diazepam-induced decrease in histamine turnover in mouse brain". Eur J Pharmacol. 124 (3): 337–42. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(86)90236-0. PMID 3089825.

- Allen MD, Greenblatt DJ, Arnold JD (1979). "Single- and multiple-dose kinetics of estazolam, a triazolo benzodiazepine". Psychopharmacology. 66 (3): 267–74. doi:10.1007/BF00428318. PMID 43552.

- Mancinelli A, Guiso G, Garattini S, Urso R, Caccia S (March 1985). "Kinetic and pharmacological studies on estazolam in mice and man". Xenobiotica. 15 (3): 257–65. doi:10.3109/00498258509045357. PMID 2862746.

- Miura M, Otani K, Ohkubo T (May 2005). "Identification of human cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the formation of 4-hydroxyestazolam from estazolam". Xenobiotica. 35 (5): 455–65. doi:10.1080/00498250500111612. PMID 16012077.

- Wang JS, DeVane CL (2003). "Pharmacokinetics and drug interactions of the sedative hypnotics" (PDF). Psychopharmacol Bull. 37 (1): 10–29. doi:10.1007/BF01990373. PMID 14561946. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-09.

- Miura M, Ohkubo T, Sugawara K, Okuyama N, Otani K (May 2002). "Determination of estazolam in plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography with solid-phase extraction" (PDF). Anal Sci. 18 (5): 525–8. doi:10.2116/analsci.18.525. PMID 12036118.

- Watanabe S; Ohta H; Sakurai Y; Takao K; Ueki S. (July 1986). "[Electroencephalographic effects of 450191-S and its metabolites in rabbits with chronic electrode implants]". Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 88 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1254/fpj.88.19. PMID 3758874.

- Johanson CE (March 1987). "Benzodiazepine self-administration in rhesus monkeys: estazolam, flurazepam and lorazepam". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 26 (3): 521–6. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(87)90159-6. PMID 2883668.

- Griffiths RR, Johnson MW (2005). "Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 Suppl 9: 31–41. PMID 16336040.

- Food and Drug Administration; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (10 March 1998). "FDA WARNS CONSUMERS AGAINST TAKING DIETARY SUPPLEMENT "SLEEPING BUDDHA"". FDA. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- "Potentially habit-forming herbal sleep aid recalled". CBC News. Feb 23, 2007. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- André, Picard (Aug 14, 2007). "Losing sleep over 'natural' aids". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2020-07-03.