Incendiary device

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires or destroy sensitive equipment using fire (and sometimes used as anti-personnel weaponry), that use materials such as napalm, thermite, magnesium powder, chlorine trifluoride, or white phosphorus. Though colloquially often known as bombs, they are not explosives but in fact are designed to slow the process of chemical reactions and use ignition rather than detonation to start or maintain the reaction. Napalm for example, is petroleum especially thickened with certain chemicals into a 'gel' to slow, but not stop, combustion, releasing energy over a longer time than an explosive device. In the case of napalm, the gel adheres to surfaces and resists suppression.

Pre-modern history

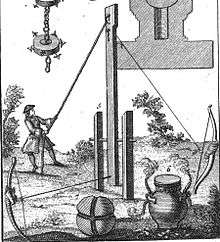

A range of early thermal weapons were in use ancient and early armies using hot pitch, oil, resin, animal fat and other similar compounds. Substances such as quicklime and sulfur could be toxic and blinding. Incendiary mixtures, such as the petroleum-based Greek fire, were launched by throwing machines or administered through a siphon. Sulfur- and oil-soaked materials were sometimes ignited and thrown at the enemy, or attached to spears, arrow and bolts and fired by hand or machine. Some siege techniques—such as mining and boring—relied on combustibles and fire to complete the collapse of walls and structures.

Towards the latter part of the period, gunpowder was invented, which increased the sophistication of the weapons, starting with fire lances.

Development and use in World War I

The first incendiary devices to be dropped during World War I fell on coastal towns in the south west of England on the night of 18–19 January 1915. The small number of German bombs, also known as firebombs, were finned containers filled with kerosene and oil and wrapped with tar-covered rope. They were dropped from Zeppelin airships. On 8 September 1915, Zeppelin L-13 dropped a large number of firebombs, but even then the results were poor and they were generally ineffective in terms of the damage inflicted. They did have a considerable effect on the morale of the civilian population of the United Kingdom.[1]

After further experiments with 5-litre barrels of benzol, in 1918, the B-1E Elektron fire bomb (German: Elektronbrandbombe) was developed by scientists and engineers at the Griesheim-Elektron chemical works. The bomb was ignited by a thermite charge, but the main incendiary effect was from the magnesium and aluminium alloy casing, which ignited at 650° Celsius, burned at 1,100 °C and emitted vapour that burned at 1,800 °C. A further advantage of the alloy casing was its lightness, being a quarter of the density of steel, which meant that each bomber could carry a considerable number.[2] The German High Command devised an operation called "The Fire Plan" (German: Der Feuerplan), which involved the use of the whole German heavy bomber fleet, flying in waves over London and Paris and dropping all the incendiary bombs that they could carry, until they were either all shot down or the crews were too exhausted to fly. The hope was that the two capitals would be engulfed in an inextinguishable blaze, causing the Allies to sue for peace.[3] Thousands of Elektron bombs were stockpiled at forward bomber bases and the operation was scheduled for August and again in early September 1918, but on both occasions, the order to take off was countermanded at the last moment, perhaps because of the fear of Allied reprisals against German cities.[4] The Royal Air Force had already used their own "Baby" Incendiary Bomb (BIB) which also contained a thermite charge.[5] A plan to fire bomb New York with new long range Zeppelins of the L70 class was proposed by the naval airship fleet commander Peter Strasser in July 1918, but it was vetoed by Admiral Reinhard Scheer.[6]

Development and use in World War II

Incendiary bombs were used extensively in World War II as an effective bombing weapon, often in a conjunction with high-explosive bombs.[7] Probably the most famous incendiary attacks are the bombing of Dresden and the bombing of Tokyo on 10 March 1945. Many different configurations of incendiary bombs and a wide range of filling materials such as isobutyl methacrylate (IM) polymer, napalm, and similar jellied-petroleum formulas were used, many of them developed by the US Chemical Warfare Service. Different methods of delivery, e.g. small bombs, bomblet clusters and large bombs, were tested and implemented.[8] For example, a large bomb casing was filled with small sticks of incendiary (bomblets); the casing was designed to open at altitude, scattering the bomblets in order to cover a wide area. An explosive charge would then ignite the incendiary material, often starting a raging fire. The fire would burn at extreme temperatures that could destroy most buildings made of wood or other combustible materials (buildings constructed of stone tend to resist incendiary destruction unless they are first blown open by high explosives).

The German Luftwaffe started the war using the 1918-designed one-kilogram magnesium alloy B-1E Elektronbrandbombe; later modifications included the addition of a small explosive charge intended to penetrate the roof of any building which it landed on. Racks holding 36 of these bombs were developed, four of which could, in turn, be fitted to an electrically triggered dispenser so that a single He 111 bomber could carry 1,152 incendiary bombs, or more usually a mixed load. Less successful was the Flammenbombe, a 250 kg or 500 kg high explosive bomb case filled with an inflammable oil mixture, which often failed to detonate and was withdrawn in January 1941.[9]

In World War II, incendiaries were principally developed in order to destroy the many small, decentralised war industries located (often intentionally) throughout vast tracts of city land in an effort to escape destruction by conventionally aimed high-explosive bombs. Nevertheless, the civilian destruction caused by such weapons quickly earned them a reputation as terror weapons with the targeted populations. The Nazi regime began the campaign of incendiary bombings at the start of World War II with the bombing of Warsaw, and continued with the London Blitz and the bombing of Moscow, among other cities. Later, an extensive reprisal was enacted by the Allies in the strategic bombing campaign that led to the near-annihilation of many German cities. In the Pacific War, during the last seven months of strategic bombing by B-29 Superfortresses in the air war against Japan, a change to firebombing tactics resulted in the death of 500,000 Japanese and the homelessness of five million more. Sixty-seven Japanese cities lost significant areas to incendiary attacks. The most deadly single bombing raid in history was Operation Meetinghouse, an incendiary attack that killed some 100,000 Tokyo residents in one night.

The 4 lb (1.8 kg) incendiary bomb, developed by ICI, was the standard light incendiary bomb used by RAF Bomber Command in very large numbers, declining slightly in 1944 to 35.8 million bombs produced (the decline being due to more bombs arriving from the United States). It was the weapon of choice for the British "dehousing" plan. The bomb consisted of a hollow body made from aluminium-magnesium alloy with a cast iron/steel nose, and filled with thermite incendiary pellets. It was capable of burning for up to ten minutes. There was also a high explosive version and delayed high explosive versions (2–4 minutes) which were designed to kill rescuers and firefighters. It was normal for a proportion of high explosive bombs to be dropped during incendiary attacks in order to expose combustible material and to fill the streets with craters and rubble, hindering rescue services.

Towards the end of World War Two, the British introduced a much improved 30 lb (14 kg) incendiary bomb, whose fall was retarded by a small parachute and on impact sent out an extremely hot flame for 15 ft (4.6 m); This, the Incendiary Bomb, 30-lb., Type J, Mk I,[10] burned for approximately two minutes. Articles in late 1944 claimed that the flame was so hot it could crumble a brick wall. For propaganda purposes the RAF dubbed the new incendiary bomb the Superflamer.[11] Around fifty-five million incendiary bombs were dropped on Germany by Avro Lancasters alone.

Many incendiary weapons developed and deployed during World War II were in the form of bombs and shells whose main incendiary component is white phosphorus (WP), and can be used in an offensive anti-personnel role against enemy troop concentrations, but WP is also used for signalling, smoke screens, and target-marking purposes. The U.S. Army and Marines used WP extensively in World War II and Korea for all three purposes, frequently using WP shells in large 4.2-inch chemical mortars. WP was widely credited by many Allied soldiers for breaking up numerous German infantry attacks and creating havoc among enemy troop concentrations during the latter part of World War II. In both World War II and Korea, WP was found particularly useful in overcoming enemy human wave attacks.

Post World War II incendiary weapons

Modern incendiary bombs usually contain thermite, made from aluminium and ferric oxide. It takes very high temperatures to ignite, but when alight, it can burn through solid steel. In World War II, such devices were employed in incendiary grenades to burn through heavy armour plate, or as a quick welding mechanism to destroy artillery and other complex machined weapons.

A variety of pyrophoric materials can also be used: selected organometallic compounds, most often triethylaluminium, trimethylaluminium, and some other alkyl and aryl derivatives of aluminium, magnesium, boron, zinc, sodium, and lithium, can be used. Thickened triethylaluminium, a napalm-like substance that ignites in contact with air, is known as thickened pyrophoric agent, or TPA.

Napalm was widely used by the United States during the Korean War,[12] most notably during the battle "Outpost Harry" in South Korea during the night of June 10–11, 1953. Eighth Army chemical officer Donald Bode reported that on an "average good day" UN pilots used 70,000 gallons of napalm, with approximately 60,000 gallons of this thrown by US forces.[13] Winston Churchill, among others, criticized American use of napalm in Korea, calling it "very cruel", as the US/UN forces, he said, were "splashing it all over the civilian population", "tortur[ing] great masses of people". The American official who took this statement declined to publicize it.[14]

During the Vietnam War, the U.S. Air Force developed the CBU-55, a cluster bomb incendiary fuelled by propane, a weapon that was used only once in warfare.[15] Napalm however, became an intrinsic element of U.S. military action during the Vietnam War as forces made increasing use of it for its tactical and psychological effects. Reportedly about 388,000 tons of U.S. napalm bombs were dropped in the region between 1963 and 1973, compared to 32,357 tons used over three years in the Korean War, and 16,500 tons dropped on Japan in 1945.[16][17]

Napalm proper is no longer used by the United States, although the kerosene-fuelled Mark 77 MOD 5 Firebomb is currently in use. The United States has confirmed the use of Mark 77s in Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003.

Incendiary weapons and laws of warfare

Signatory states are bound by Protocol III of the UN Convention on Conventional Weapons which governs the use of incendiary weapons:

- prohibits the use of incendiary weapons against civilians (effectively a reaffirmation of the general prohibition on attacks against civilians in Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions)

- prohibits the use of air-delivered incendiary weapons against military targets located within concentrations of civilians and loosely regulates the use of other types of incendiary weapons in such circumstances.[18]

Protocol III states though that incendiary weapons do not include:

- Munitions which may have incidental incendiary effects, such as illuminates, tracers, smoke or signaling systems;

- Munitions designed to combine penetration, blast or fragmentation effects with an additional incendiary effect, such as armor-piercing projectiles, fragmentation shells, explosive bombs and similar combined-effects munitions in which the incendiary effect is not specifically designed to cause burn injury to persons, but to be used against military objectives, such as armoured vehicles, aircraft and installations or facilities.

See also

- Arson

- Bat bomb

- Driptorch

- Early thermal weapons

- Fire accelerant

- Fire balloon

- Firestorm

- Flame fougasse

- Flamethrower

- Greek fire (Historic Byzantine incendiary weapon)

- High explosive incendiary (HEI)

- Incendiary ammunition

- Meng Huo You (Historic Chinese incendiary weapon)

- Molotov cocktail

- Napalm

- Pen Huo Qi (Historic Chinese flamethrower)

- Stinkpot (Historic Chinese incendiary weapon)

References

- Wilbur Cross, "Zeppelins of World War I" page 35, published 1991 Paragon House ISBN I-56619-390-7

- Hanson, Neil (2009), First Blitz, Corgi Books, ISBN 978-0552155489 (pp. 406–408)

- Hanson, pp. 413–414

- Hanson, pp. 437–438

- Dye, Peter (2009). "ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 45 – RFC BOMBS & BOMBING 1912–1918 (pp. 12–13)" (PDF). www.raf.mod.uk. Royal Air Force Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- Hanson, p. 412

- World War II Guide. Archived 30 August 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- "How we fight Japan with fire". Popular Science. May 1945. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- "German Ordnance". The Doric Columns. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- Hussey, G.F., Jr. (4 January 1970) [6 October 1946]. "British English Ordnance" (PDF). Command Naval Ordnance Systems. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "SUPERFLAMER Dropped by Chute Throws Fire 15 Feet." Popular Mechanics, December 1944, p. 13. Article bottom of page.

- Pike, John. "Napalm".

- Neer, Robert (2013). Napalm: An American Biography. Harvard University Press. p. 99.

- Neer, Robert M. (2013). Napalm: An American Biography. Harvard University Press. pp. 102–3.

- Alan Dawson, 55 Days: The Fall of South Vietnam (Prentice-Hall 1977).

- "Books in brief. Napalm: An American Biography Robert M. Neer Harvard University Press 352 pp". Nature. 496 (7443): 29. 2013. doi:10.1038/496029a.

- "Liquid Fire – How Napalm Was Used In The Vietnam War". www.warhistoryonline.com. Nikola Budanovic. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- although the 4th Geneva Convention, Part 3, Article 1, Section 28 states "The presence of a protected person(s) may not be used to render certain points or areas immune from military operations."

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Incendiary weapons. |

- Protocol III to the Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons which may be deemed to be Excessively Injurious or to have Indiscriminate Effects

- United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific War) 1946

- Fire From The Sky 1944 article on the production of incendiary bombs

- AN-M50-series incendiary bombs (German)