Panay

Panay is the sixth-largest and fourth most-populous island in the Philippines, with a total land area of 12,011 km2 (4,637 sq mi) and with a total population of 4,477,247. Panay comprises 4.4 percent of the entire population of the country.[1] The City of Iloilo is its largest settlement with a total population of 447,992 inhabitants. It is a triangular island, located in the western part of the Visayas. It is about 160 km (99 mi) across. It is divided into four provinces: Aklan, Antique, Capiz and Iloilo, all in the Western Visayas Region. Just closely off the mid-southeastern coast lies the island-province of Guimaras. It is located southeast of the island of Mindoro and northwest of Negros across the Guimaras Strait. To the north and northeast is the Sibuyan Sea, Jintotolo Channel and the island-provinces of Romblon and Masbate; to the west and southwest is the Sulu Sea and the Palawan archipelago[2] and to the south is Panay Gulf. Panay is the only main island in the Visayas whose provinces don't bear the name of their island.

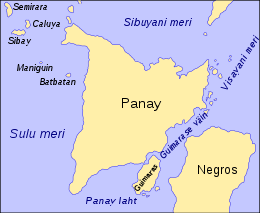

Panay Island map (in Estonian language) showing adjacent Guimaras and Negros Islands | |

.svg.png) Panay Location within the Philippines | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | South East Asia |

| Coordinates | 11°09′N 122°29′E |

| Archipelago | Visayas |

| Adjacent bodies of water | |

| Area | 12,011 km2 (4,637 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 65th |

| Highest elevation | 2,117 m (6,946 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Madia-as |

| Administration | |

| Region | Western Visayas |

| Provinces | |

| Largest settlement | Iloilo City (pop. 447,992) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 4,477,247 (2015) |

| Pop. density | 349.0/km2 (903.9/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | |

Panay is bisected by the Central Panay Mountain Range, its longest mountain chain. The island has many rivers, the longest being the Panay River at a length of 152 kilometres (94 mi), followed by the Jalaur, Aklan, Sibalom, Iloilo and Bugang rivers. Standing at about 2,117 m (6,946 ft), the dormant Mount Madia-as (situated in Culasi, Antique) is the highest point of the island, with Mount Nangtud (located between Barbaza, Antique and Jamindan, Capiz) following next at 2,073 m (6,801 ft).

History

Etymology

Before 1212, Panay was called Simsiman. The community is located at the shores of the Ulian River and was linked by a creek. The creek provided salt to the Ati people as well as animals which lick the salt out of the salty water. Coming from the root word "simsim", "simsimin" means "to lick something to eat or to drink", thus the place was called Simsiman.

The native Ati called the island Aninipay from words "ani" to harvest and "nipay", a hairy grass abundant in the whole Panay.

Before the arrival of the Europeans

No pre-Hispanic written accounts of Iloilo and Panay island exist today. Oral traditions, in the form of recited epics like the Hinilawod, has survived to a small degree. A few recordings of these epic poems exist. The most notable are the works of noted Filipino Anthropologist Felipe Jocano.[3]

While no current archaeological evidence exist describing pre-Hispanic Panay, an original work by Pedro Alcantara Monteclaro published in 1907 called Maragtas details the alleged accounts of the founding of the various pre-Hispanic polities on Panay Island. The book is based on oral and written accounts available to the author at the time.[4] The author made no claim on the historical accuracy of the accounts. [5]

According to Maragtas, the Kedatuan of Madja-as was founded after ten datus fled Borneo and landed on Panay Island. The book then goes on to detail their subsequent purchase of the coastal lands in which they settled from the native Ati people.

An old manuscript Margitas of uncertain date (discovered by the anthropologist H. Otley Beyer)[6] give interesting details about the laws, government, social customs, and religious beliefs of the early Visayans, who settled Panay within the first half of the thirteenth century.[7] The term Visayan was first applied only to them and to their settlements eastward in the island of Negros, and northward in the smaller islands, which now compose the province of Romblon. In fact, even at the early part of Spanish colonialization of the Philippines, the Spaniards used the term Visayan only for these areas. While the people of Cebu, Bohol, and Leyte were for a long time known only as Pintados. The name Visayan was later extended to them because, as several of the early writers state, their languages are closely allied to the Visayan dialect of Panay.[8]

Grabiel Ribera, captain of the Spanish royal infantry in the Philippine Islands, also distinguished Panay from the rest of the Pintados Islands. In his report (dated 20 March 1579) regarding a campaign to pacify the natives living along the rivers of Mindanao (a mission he received from Dr. Francisco de Sande, Governor and Captain-General of the Archipelago), Ribera mentioned that his aim was to make the inhabitants of that island "vassals of King Don Felipe… as are all the natives of the island of Panay, the Pintados Islands, and those of the island of Luzon…"[9]

During the early part of the colonial period in the Archipelago, the Spaniards led by Miguel López de Legazpi transferred their camp from Cebu to Panay in 1569. On 5 June 1569, Guido de Lavezaris, the royal treasurer in the Archipelago, wrote to Philip II reporting about the Portuguese attack to Cebu in the preceding autumn. A letter from another official, Andres de Mirandaola (dated three days later, 8 June), also described briefly this encounter with the Portuguese. The danger of another attack led the Spaniards to remove their camp from Cebu to Panay, which they considered a safer place. Legazpi himself, in his report to the Viceroy in New Spain (dated 1 July 1569), mentioned the same reason for the relocation of Spaniards to Panay.[10] It was in Panay that the conquest of Luzon was planned, and later launched on 8 May 1570.[11]

The account of early Spanish explorers

During the early part of the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, the Spanish Augustinian Friar Gaspar de San Agustín, O.S.A. described Panay as: "…very similar to that of Sicily in its triangular form, as well as in it fertility and abundance of provision. It is the most populated island after Manila and Mindanao, and one of the largest (with over a hundred leagues of coastline). In terms of fertility and abundance, it is the first. […] It is very beautiful, very pleasant, and full of coconut palms… Near the river Alaguer (Halaur), which empties into the sea two leagues from the town of Dumangas…, in the ancient times, there was a trading center and a court of the most illustrious nobility in the whole island."[12] Padre Francisco Colin (1592-1660), an early Jesuit missionary and Provincial of his Order in the Philippines also records in the chronicles of the Society of Jesus (published later in 1663 as Labor euangelica) that Panay is the island which is most abundant and fertile.[13]

The first Spanish settlement in Panay island and the second oldest Spanish settlement in the Philippines was established by the Miguel Lopez de Legazpi expedition in Panay, Capiz at the banks of the Panay River[14] in northern Panay, the name of which was extended to the whole Panay island. Legazpi transferred the capital there from Cebu since it had abundant provisions and was better protected from Portuguese attacks before the capital was once again transferred to Manila.[15]

Miguel de Luarca, who was among the first Spanish settlers in the Island, made one of the earliest account about Panay and its people according to a Westerner's point of view. In June 1582, while he was in Arevalo (Iloilo), he wrote in his Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas the following observations:

The island is the most fertile and well-provisioned of all the islands discovered, except the island of Luzon: for it is exceedingly fertile, and abounds in rice, swine, fowls, wax, and honey; it produces also a great quantity of cotton and abacá fiber.[16]

"The villages are very close together, and the people are peaceful and open to conversion. The land is healthful and well-provisioned, so that the Spaniards who are stricken in other islands go thither to recover their health."[16]

"The natives are healthy and clean, and although the island of Cebu is also healthful and had a good climate, most of its inhabitants are always afflicted with the itch and buboes. In the island of Panay, the natives declare that no one of them had ever been afflicted with buboes until the people from Bohol – who, as we said above, abandoned Bohol on account of the people of Maluco – came to settle in Panay, and gave the disease to some of the natives. For these reasons the governor, Don Gonzalo Ronquillo, founded the town of Arevalo, on the south side of this island; for the island runs north and south, and on that side live the majority of the people, and the villages are near this town, and the land here is more fertile."[16] This probably explains why there are reference of presence of Pintados in the Island.

"The island of Panay provides the city of Manila and other places with a large quantity of rice and meat…".[17].. "As the island contains great abundance of timber and provisions, it has almost continuously had a shipyard on it, as is the case of the town of Arevalo, for galleys and fragatas. Here the ship 'Visaya' was launched."[18]

Another Spanish chronicler in the early Spanish period, Dr. Antonio de Morga (Year 1609) is also responsible for recording other Visayan customs. Customs such as Visayans' affinity for singing among their warrior-castes as well as the playing of gongs and bells in naval battles.

Their customary method of trading was by bartering one thing for another, such as food, cloth, cattle, fowls, lands, houses, fields, slaves, fishing-grounds, and palm-trees (both nipa and wild). Sometimes a price intervened, which was paid in gold, as agreed upon, or in metal bells brought from China. These bells they regard as precious jewels; they resemble large pans and are very sonorous. They play upon these at their feasts, and carry them to the war in their boats instead of drums and other instruments.[19]

The early Dutch fleet commander Cornelis Matelieff de Jonge called at Panay in 1607. He mentions a town named "Oton" on the island where there were "18 Spanish soldiers with a number of other Spanish inhabitants so that there may be 40 whites in all". He explained that "a lot of rice and meat is produced there, with which they [i.e. the Spanish] supply Manila."[20]

According to Stephanie J. Mawson, using recruitment records found in Mexico, in addition to the 40 Caucasian Spaniards who then lived in Oton, there were an additional set of 66 Mexican soldiers of Mulatto, Mestizo or Native American descent sentried there during the year 1603.[21] However, the Dutch visitor, Cornelis Matelieff de Jongedid, did not count them in since they were not pure whites like him.

Iloilo City in Panay was awarded by the Queen of Spain the title: "La Muy Leal y Noble Ciudad de Iloilo (The Most Loyal and Noble City) for being the most loyal and noble city in the Spanish Empire since it clung on to Spain amidst the Philippine revolution the last nation to revolt against Spain in the Spanish Empire.

Nearby Boracay island was considered the most beautiful island in the world by several travel magazines.

The island lent its name to several United States Navy vessels including the USS Panay (PR-5), sunk in 1937 by the Japanese in the Panay incident.

Geography

Mount Madia-as, is the highest point in Panay Island standing at 6,946 ft. (2,117 m ) above sea level, located in the Northern province of Antique. Boracay, an island 2 kilometres (1.2 miles) to the northwest tip of Panay Island and part of Aklan province, is a popular tourist destination.

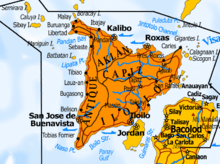

Administrative divisions

The island is covered by 4 provinces, 92 municipalities, and, as of 2014, 3 cities (93 municipalities if the associated islands of Caluya are included), all under the jurisdiction of the Western Visayas region.

| Seal | Province | Population (2015)[22][23] |

Land area | Population Density | Capital | Municipalities (including associated islands*) |

Cities | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aklan | 574,823 | 1,821.42 km2 (703.25 sq mi) |

290/km2 (750/sq mi) |

Kalibo | 17 towns

|

— |  | |

|

Antique | 582,012 | 2,729.17 km2 (1,053.74 sq mi) |

200/km2 (520/sq mi) |

San Jose de Buenavista | 18 towns

|

— |  |

| Capiz | 761,384 | 2,594.64 km2 (1,001.80 sq mi) |

280/km2 (730/sq mi) |

Roxas | 16 towns

|

Roxas |  | |

|

Iloilo | 2,384,415 | 5,079.17 km2 (1,961.08 sq mi) |

440/km2 (1,100/sq mi) |

Iloilo City | 42 towns

|

| |

| Seal | Province | Population (2015) |

Land area | Density | Capital | Municipalities | Cities | Location |

|

Notes: The municipality of Caluya in Antique province is covered by separate islands which are included under the island group of Panay. Iloilo figures include the independent city of Iloilo. | ||||||||

Caves

This survey was made possible through the help of the Victoria Archaeological Society (VAS) who in 1975 offered their assistance into surveying the Island of Panay.[24]

Lapuz Lapuz

Lapuz Lapuz Cave is located in the village of Moroboro in Dingle, Iloilo. Lapuz Lapuz is named so because it has an entrance from either end. It is approximately 90-metre (300 ft) long and located in a mountainous terrain. Its closest source of water is Butac Cave; next closest is the Jalaur river. It was occupied about 800 years ago. Used for no more than 200 years; occupied intensively occasionally rather than continuously.

Cultural layers are strongly alkaline. Cultural sediments are mostly clay and silty foam with some debris from the roof of the cave. A significant number of this must have come from the outside, possibly due to erosion or due to large amounts of leaching.

Two species of bat inhabit Lapuz Lapuz cave: species Eonycteris Longicaudea and genus Pipistrellus. Based on archaeological evidence, remains of larger animals were dumped in the rear of the cave while the bats were dumped near the entrance of the cave. Deer, Pig, Civet, Rat, Monkey, Lizard, Snake, Turtle, Crab, Frog and Fish remains were found as well.

Earthenware found was most likely shaped by a paddle and an anvil. The paddles mostly used for decorative than utilitarian purposes. Most sherds appear to have been used for cooking, because its parts are blackened to some extent; deposits of carbon also found inside the pots. The other sherds were used either as bowls or goblets. Most of the vessels were made in the Philippines. Due to the absence of beads, other ornaments and high pottery densities, it could be concluded that the cave was once a transitory hunting and gathering camp.

Snail shells found are mainly of the genera Rhysota, Helicostyla, Cyclophorus and Obba. The most often occurring of which is Rhysota, mainly because it’s the most economic snail. Rhysota has the highest yield of meat for the weight of the shell compared to the other genera. Rhysota is also the most occurring unlike Helicostyla. Unlike the genera Thiara which requires a drier month for it to be collected from the banks of the nearest river, Rhysota is more accessible. This diet could be explained by the fact that the hunters hunted extensively and so they had to rely on a diet of molluscs.

Majority of the waste flakes are made from chert. The presence of waterworn cobbles suggests that most of the material used came from a gravel bed such as those found in the Jalaud river. Most of the stone tools were used for butchering, hunting, processing and manufacturing of bone/antler tools

Naulan

Naulan Cave is situated at the foot of Mt. Agmasibes in Barangay Concepcion, Municipality of Dumalag, Capiz. It is around 1.5 km (0.9 mi) west of the Panay river, the Panay river being sandwiched between rugged limestone mountains (Mt. Paginraon and Mt. Agbadiang). Naulan cave is 18 metres (59 feet) long and 5 metres (16 feet) outward. It is estimated to be 800 B.P. old.

There are three caves within the vicinity, all of which are habitable by humans but doesn’t show any evidence of human habitation. This is probably because the Naulan rock shelter has a more accommodating environment. No sources of water have been found in the immediate vicinity of the caves or the rock shelter.

Sediments are highly alkaline, favoring the preservation of bone. There is approximately 120 cm (47 in) of deposit, fairly uniform in depth. The deposit is mostly midden, containing concentrations of bone, shell, some stone and little charcoal

Thiara Tuberculata composes 78% weight wise and Rhysota composes 7-15% of the total weight of shells. However, Rhysota still significantly contributes to the total meat weight. Naulan Cave’s taxonomy is the same with the Lapuz Lapuz cave except for the lack of civets. In terms of animals, the major target was deer for most of the habitation while pig was being targeted more during the later years. Like Lapuz Lapuz, Naulan was also a hunting assemblage where animals were butchered and their bones broken into splinters by some form of heat treatment.

The earthenware found inside the cave were polished utilitarian vessels, mainly for cooking. For the rest of the habitation of the cave, there were no changes in the design and function of the earthenware. Minerals such as hornblende, quartz and a red crypto-crystalline quartz were found as inclusions of the sherds.

Langub Cave

Langub Cave can be found in Barrio Dolores, Dumalag, Capiz. It is southeast of Naulan and surrounded by a light rainforest. Its entrance is 27 metres (89 ft) wide and 20 meters although the eastern side is blocked by a rock fall. The floor of the cave is flat but filled with damp and slippery clay. It could be 4000-1000 B.P. old. Like Naulan and Lapuz Lapuz cave, Langub was a hunter-gatherer site where the hunting parties brought earthenware occasionally.

There were six species present in the analysis of the mollusks. However, Rhysota rhea and Thiara tuberculata were the most common species found. Rhysota rhea composes 95% of shell meat contribution meaning there was a consistent collection of this species from the forest environment. Thiara, on the other hand, is due to the fact that the site is closer to a spring where they were collected.

Of the bones found, most of these were for smaller animals such as bats. Remains of rodent, reptile, pig, civet, fish and deer were found. The cave shows signs of butchering but no presence of bone or antler tools.

Stone tools found in the cave were made from cryptoscalline quartz, andesite, basalt and granite. Although majority of the stone tools were made from cryptoscalline quartz. Most tools found were utilitarian. Earthenware pottery was rare.

Gui-ub Cave

Gui-ub cave is a large rock shelter found in Barangay Tigbayog, Calinog, Iloilo. It is located in the mountain chain dividing Iloilo from Antique. Gui-ub’s location could have been a very rich source of resources before deforestation occurred around the 1940s.

The floor of the shelter is flat and dry. The walls are made up of a coarse conglomerate, which weathered and eventually covered the floor with small waterworn pebbles. Floor deposits are full of small holes because of termites.

Mollusc analysis showed that there were very few shells present in the layers. Shells seem to be of little importance to the economy of Gui-ub cave. Skeletal analysis shows remains of pig, deer, monkey, civet, cat, dog, bat, reptile, fish, rat, bird and crustacean. The primary targets of the people residing in Gui-ub were mostly large animals (pig and deer) and only took smaller animals when the opportunity presents itself. The presence of two young dogs suggests that they were probably domesticated. A large reptilian vertebrae was also found which can only come from a reptile as large as a crocodile. It could have been a large, extinct species of turtle.

Earthenware, in general, were utilitarian, smoothed, polished, unslipped and fired at low temperatures. They were probably shaped with a paddle and an anvil. Two sherds have charcoal deposits indicating that these were once charcoal burners or stoves.

Most of the evidence uncovered was made of cryptocrystalline quartz. The others were composed of hornfels and andesite.

Pilar

The Pilar Caves are located in Pilar Municipality, Capiz. Many of the caves were damaged due to guano digging. In search of a site with archaeological artifacts in their original places, an overhang was examined.

The overhang was dated based on a charcoal sample found. The site was occupied just before the Spanish occupation (1521). Inhabitants of the Pilar site were also hunter gatherers like the inhabitants of other sites in Panay Island. The difference is that the Pilar people had metal to arm their weapons with

By weight the most important species are Turritela, Melanoides, Tegillarca and Ostrea for the more recent layers; Nerita, Ostrea and Melanoides for the older layers. Very few of the shells are burnt.

Remains of pig, deer, rodent, reptile, monkey, crab and fish were found. Presence of human molars and mammal long bone fragments implies the possibility of the place being used as a burial site. The limited remains of the animals such as the pig suggests that the animals could have been domesticated for food.

See also

- Macario Peralta, Jr.

- Panay Railways

- Church of Panay

References

- Boquet, Yves (2017). The Philippine Archipelago. Springer. p. 16. ISBN 9783319519265.

- C.Michael Hogan. 2011. Sulu Sea

- Jocano, Felipe Landa; Hugan-an (2000). Hinilawod: Adventures of Humadapnon Tarangban I. Quezon City: Punlad Research House, Inc. ISBN 971-622-010-3.

- Ma. Cecilia Locsin-Nava (2001). History & Society in the Novels of Ramon Muzones. Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 46. ISBN 978-971-550-378-5.

- Originally titled Maragtás kon (historia) sg pulô nga Panay kutub sg iya una nga pamuluyö tubtub sg pag-abut sg mga taga Borneo nga amó ang ginhalinan sg mga bisayâ kag sg pag-abut sg mga Katsilâ, Scott 1984, pp. 92–93, 103

- Scott, William Henry, Pre-hispanic Source Materials for the study of Philippine History, 1984: New Day Publishers, pp. 101, 296.

- G. Nye Steiger, H. Otley Beyer, Conrado Benitez, A History of the Orient, Oxford: 1929, Ginn and Company, p. 122.

- G. Nye Steiger, H. Otley Beyer, Conrado Benitez, A History of the Orient, Oxford: 1929, Ginn and Company, pp. 122–123.

- Cf. BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds. (1911). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 04 of 55 (1493–1803). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", pp. 257–260.

- Cf. BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds. (1911). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 03 of 55 (1493–1803). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", pp. 15–16.

- Cf. BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds. (1911). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 03 of 55 (1493–1803). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 73.

- Mamuel Merino, O.S.A., ed., Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1565–1615), Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, 1975, pp. 374–376.

- Francisco Colin, S.J., Labor euangelica, ministerios apostolicos de los obreros de la Compañia de Iesus : fundacion, y progressos de su Prouincia en las islas Filipinas historiados, Madrid:1663, Lib. I, Cap. VII, p. 63.

- Location of the Panay River Basin

- "The First Spanish Settlement in Panay" By Henry F. Funtecha PUBLISHED IN: The News Today.

- Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) in BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 67.

- Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) in BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 69.

- Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (Arevalo: June 1582) in BLAIR, Emma Helen & ROBERTSON, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704. "Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.", p. 71.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-09. Retrieved 2014-09-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Peter Borschberg, Journal, Memorials and Letters of Cornelis Matelieff de Jonge. Security, Diplomacy and Commerce in 17th-century Southeast Asia, ed. BORSCHBERG, Peter (2015) Singapore: NUS Press, ISBN 978-9971-69-798-3, p. 565-6.

- Convicts or Conquistadores? Spanish Soldiers in the Seventeenth-Century Pacific By Stephanie J. Mawson

- Census of Population (2015). Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population. PSA. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "PSGC Interactive; List of Provinces". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Coutts, P. (1983). An archaeological perspective of Panay Island, Philippines. Cebu City: University of San Carlos.

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Panay. |

| Look up Panay in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panay. |

Bibliography

- C. Michael Hogan. 2011. Sulu Sea. Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. P. Saundry & C. J. Cleveland. Washington DC