Anglo-Japanese Alliance

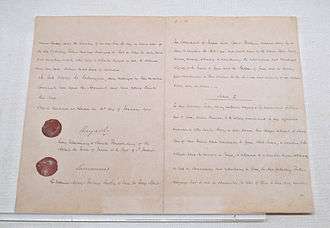

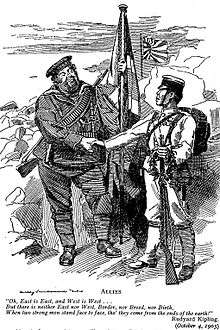

The first Anglo-Japanese Alliance (日英同盟, Nichi-Ei Dōmei) was an alliance between Britain and Japan, signed in January 1902.[1] The alliance was signed in London at Lansdowne House on 30 January 1902 by Lord Lansdowne, British foreign secretary, and Hayashi Tadasu, Japanese diplomat.[2] A diplomatic milestone that saw an end to Britain's splendid isolation, the alliance was renewed and expanded in scope twice, in 1905 and 1911, before its demise in 1921 and termination in 1923.[3] The main threat for both sides was from Russia. The threat of war with Britain prevented France from joining its ally Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904. However, it angered the United States and some British dominions, which were hostile to Japan.[4]

Motivations and reservations

The possibility of an alliance between Great Britain and Japan had been canvassed since 1895, when Britain refused to join the Triple Intervention of France, Germany and Russia against the Japanese occupation of the Liaodong Peninsula. While this single event was an unstable basis for an alliance, the case was strengthened by the support Britain had given Japan in its drive towards modernisation and their co-operative efforts to put down the Boxer Rebellion.[5] Newspapers of both countries voiced support for such an alliance; in Britain, Francis Brinkley of The Times and Edwin Arnold of the Telegraph were the driving force behind such support, while in Japan the pro-alliance mood of politician Ōkuma Shigenobu stirred the Mainichi and Yomiuri newspapers into pro-alliance advocacy. The 1894 Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation had also paved the way for equal relations and the possibility of an alliance.[6]

In the end, the common interest truly fuelling the alliance was opposition to Russian expansion. This was made clear as early as the 1890s, when the British diplomat Cecil Spring Rice identified that Britain and Japan working in concert was the only way to challenge Russian power in the region.[7] Negotiations began when Russia began to move into China. Nevertheless, both countries had their reservations. Britain was cautious about abandoning its policy of "splendid isolation", wary of antagonizing Russia, and unwilling to act on the treaty if Japan were to attack the United States. There were factions in the Japanese government that still hoped for a compromise with Russia, including the highly powerful political figure Hirobumi Itō, who had served four terms as Prime Minister of Japan. It was thought that friendship within Asia would be more amenable to the US, which was uncomfortable with the rise of Japan as a power. Furthermore, Britain was unwilling to protect Japanese interests in Korea and likewise, the Japanese were unwilling to support Britain in India.

Hayashi and Lord Lansdowne began their discussions on July 1901, and disputes over Korea and India delayed them until November. At this point, Hirobumi Itō requested a delay in negotiations in order to attempt a reconciliation with Russia. He was mostly unsuccessful, and Britain expressed concerns over duplicity on Japan's part, so Hayashi hurriedly re-entered negotiations in 1902. "Splendid isolation" was ended as for the first time Britain saw the need for a peace-time military alliance. It was the first alliance on equal terms between East and West.[8]

Terms of the 1902 treaty

The treaty contained six articles:

Article 1

- The High Contracting parties, having mutually recognised the independence of China and Korea, declare themselves to be entirely uninfluenced by aggressive tendencies in either country, having in view, however, their special interests, of which those of Great Britain relate principally to China, whilst Japan, in addition to the interests which she possesses in China, is interested in a peculiar degree, politically as well as commercially and industrially in Korea, the High Contracting Parties recognise that it will be admissible for either of them to take such measures as may be indispensable in order to safeguard those interests if threatened either by the aggressive action of any other Power, or by disturbances arising in China or Korea, and necessitating the intervention of either of the High Contracting Parties for the protection of the lives and properties of its subjects.

Article 2

- Declaration of neutrality if either signatory becomes involved in war through Article 1.

Article 3

- Promise of support if either signatory becomes involved in war with more than one Power.

Article 4

- Signatories promise not to enter into separate agreements with other Powers to the prejudice of this alliance.

Article 5

- The signatories promise to communicate frankly and fully with each other when any of the interests affected by this treaty are in jeopardy.

Article 6

- Treaty to remain in force for five years and then at one years' notice, unless notice was given at the end of the fourth year.[9]

Articles 2 and 3 were most crucial concerning war and mutual defense.

The treaty laid out an acknowledgment of Japanese interests in Korea without obligating Britain to help should a Russo-Japanese conflict arise on this account. Japan was not obligated to defend British interests in India.

Although written using careful and clear language, the two sides understood the Treaty slightly differently. Britain saw it as a gentle warning to Russia, while Japan was emboldened by it. From that point on, even those of a moderate stance refused to accept a compromise over the issue of Korea. Extremists saw it as an open invitation for imperial expansion.

Renewal in 1905 and 1911

The alliance was renewed and extended in scope twice, in 1905 and 1911. This was partly prompted by British suspicions about Japanese intentions in South Asia. Japan appeared to support Indian nationalism, tolerating visits by figures such as Rash Behari Bose. The July 1905 renegotiations allowed for Japanese support of British interests in India and British support for Japanese progress into Korea. By November of that year, Korea was a Japanese protectorate, and in February 1906 Itō Hirobumi was posted as the Resident-General to Seoul. At the renewal in 1911, Japanese diplomat Komura Jutarō played a key role to restore Japan's tariff autonomy.[10]

Effects

The alliance was announced on 12 February 1902.[11] In response, Russia sought to form alliances with France and Germany, which Germany declined. On 16 March 1902, a mutual pact was signed between France and Russia. China and the United States were strongly opposed to the alliance. Nevertheless, the nature of the Anglo-Japanese alliance meant that France was unable to come to Russia's aid in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 as this would have meant going to war with Britain.

The alliance's provisions for mutual defence prompted Japan to enter the First World War on the British side, to overrun German colonies in China and the Pacific. Japan attacked the German base at Tsingtao in 1914 and forced the Germans to surrender (see Siege of Tsingtao). Japanese officers aboard British warships were casualties at the Battle of Jutland in 1916.[12] In 1917, Japanese warships were sent to the Mediterranean and assisted in the protection of allied shipping near Malta from U-boat attacks. A memorial at the Kalkara Naval Cemetery in Malta is dedicated to the 72 Japanese sailors who died in the conflict.[13] The Treaty also made possible the Japanese seizure of German possessions in the Pacific north of the equator during the First World War, a huge boon to Japan's imperial interests.

The alliance formed the basis for positive trading and cultural exchanges between Britain and Japan. Rapid industrialisation and the development of the Japanese armed forces provided significant new export opportunities for British shipyards and arms manufacturers. Japanese educated in Britain were also able to bring new technology to Japan, such as advances in ophthalmology. British artists of the time such as James McNeill Whistler, Aubrey Beardsley and Charles Rennie Mackintosh were heavily inspired by Japanese kimono, swords, crafts and architecture.

Limitations

There remained strains on Anglo-Japanese relations during the years of the alliance. One such strain was the racial question. Although originally a German notion, the Japanese perceived that the British had been affected by idea of Yellow Peril, on account of their recalcitrance in the face of Japanese imperial success. This issue returned at Versailles after the First World War when Britain sided with the U.S. against Japan's request of the addition of Racial Equality Proposal, proposed by Prince Kinmochi Saionji. The racial question was difficult for Britain because of its multi-ethnic empire.

Another strain was the Twenty-One Demands which Japan made of China in 1915. This unequal treaty would have given Japan varying degrees of control over all of China, and would have prohibited European powers from extending their Chinese operations any further.[14]

End of the treaty

The alliance was viewed as an obstacle already at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919–1920. On 8 July 1920, the two governments issued a joint statement to the effect that the alliance treaty "is not entirely consistent with the letter of that Covenant (of the League of Nations), which both Governments earnestly desire to respect".[16]

The demise of the alliance was signaled by the 1921 Imperial Conference, in which British and Dominion leaders convened to determine a unified international policy.[17] One of the major issues of the conference was the renewal of the Anglo–Japanese Alliance. The conference began with all but Canadian Prime Minister Arthur Meighen supporting the immediate renewal of an alliance with Japan. The prevailing hope was for a continuance of the alliance with the Pacific power, which could potentially provide security for British imperial interests in the area.[18] The Australians feared that they could not fend off any advances from the Imperial Japanese Navy, and desired a continuance of the buildup of naval resources for a possible future conflict as they feared that an alliance with the United States (then in a state of post-war isolationism) would provide little protection.[19]

Meighen, fearing that a conflict could develop between Japan and the United States, demanded the British Empire remove itself from the treaty to avoid being forced into a war between the two nations. The rest of the delegates agreed that it was best to court America and try to find a solution that the American government would find suitable, but only Meighen called for the complete abrogation of the treaty.[20] The American government feared that the renewal of the Anglo–Japanese Alliance would create a Japanese-dominated market in the Pacific, and close China off from American trade.[21] These fears were elevated by the news media in America and Canada, which reported alleged secret anti-American clauses in the treaty, and advised the public to support abrogation.[22]

The press, combined with Meighen's convincing argument of Canadian fears that Japan would attack imperial assets in China, caused the Imperial Conference to shelve the alliance.[23] The conference communicated their desire to consider leaving the alliance to the League of Nations, which stated that the alliance would continue, as originally stated with the leaving party giving the other a twelve-month notice of their intentions.[24]

The British Empire decided to sacrifice its alliance with Japan in favour of goodwill with the United States, yet it desired to prevent the expected alliance between Japan and either Germany or Russia from coming into being.[25] Empire delegates convinced America to invite several nations to Washington to participate in talks regarding Pacific and Far East policies, specifically naval disarmament.[26] Japan came to the Washington Naval Conference with a deep mistrust of Britain, feeling that London no longer wanted what was best for Japan.[27]

Despite the growing rift, Japan joined the conference in hopes of avoiding a war with the United States.[28] The Pacific powers of the United States, Japan, France and Britain would sign the Four-Power Treaty, and adding on various other countries such as China to create the Nine-Power Treaty. The Four-Power Treaty would provide a minimal structure for the expectations of international relations in the Pacific, as well as a loose alliance without any commitment to armed alliances.[29] The Four Powers Treaty at the Washington Conference made the Anglo–Japanese Alliance defunct in December, 1921; however, it would not officially terminate until all parties ratified the treaty on 17 August 1923.[30]

At that time, the Alliance was officially terminated, as per Article IV in the Anglo–Japanese Alliance Treaties of 1902 and 1911.[31] The distrust between the Commonwealth and Japan, as well as the manner in which the Anglo–Japanese Alliance concluded, are credited by many scholars as being leading causes in Japan's involvement in the World War II.[32]

See also

Notes

- Ian Nish, Anglo-Japanese Alliance: The Diplomacy of Two Island Empires 1984-1907 (1985) pp 203–228.

- "a home away from home – since 1935". The Lansdowne Club. Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- William Langer, The Diplomacy of Imperialism 1890–1902 (2nd ed. 1950), pp. 745–86.

- Nish, Anglo-Japanese Alliance: The Diplomacy of Two Island Empires 1984-1907 (1985) pp 229–245.

- G. W. Monger, "The End of Isolation: Britain, Germany and Japan, 1900–1902." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 13 (1963): 103–121.

- Zara S. Steiner, "Great Britain and the Creation of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance." Journal of Modern History 31.1 (1959): 27–36. onlinme

- Burton, David Henry (1990). Cecil Spring Rice: A Diplomat's Life. Page 100: Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3395-3.CS1 maint: location (link)

- J.D. Harcreaves, "The Anglo-Japanese Alliance" History Today (April 1952) 2#4 pp. 252–258.

- Michael Duffy (22 August 2009). "First World War.com – Primary Documents – Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 30 January 1902". google.com. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- Robert Joseph Gowen, "British Legerdemain at the 1911 Imperial Conference: The Dominions, Defense Planning, and the Renewal of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance." Journal of Modern History 52.3 (1980): 385–413 online.

- Sydney Morning Herald, 13 February 1902.

- 1916 newspaper casualty lists, Toronto Public Library.

- Zammit, Roseanne (27 March 2004). "Japanese lieutenant's son visits Japanese war dead at Kalkara cemetery". Times of Malta. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Gowen, Robert (1971). "Great Britain and the Twenty-One Demands of 1915: Cooperation versus Effacement". The Journal of Modern History. University of Chicago. 43 (1): 76–106. ISSN 0022-2801.

- "After some delay, and a failure to attend an earlier meeting, the Japanese local commander, Rear Admiral Jisaku Uzumi, came aboard HMS Nelson on the evening of 2 September, wearing the DSC he had earned as Britain's ally in the 1914–18 war, and surrendered the garrison. He fainted and was rushed to hospital; the military policemen who carried him there took his sword as a souvenir." Bayly & Harper, page 49

- Text of the statement in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 1, p. 24.

- Vinson, J. C. "The Imperial Conference of 1921 and the Anglo-Japanese alliance." Pacific Historical Review 31, no. 3 (1962): 258

- Vinson, J. C. "The Imperial Conference of 1921 and the Anglo-Japanese alliance," 258.

- Brebner, J. B. "Canada, The Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Washington Conference." Political Science Quarterly 50, no. 1 (1935): 52

- Vinson, J. C. "The Imperial Conference of 1921 and the Anglo-Japanese alliance." Pacific Historical Review 31, no. 3 (1962): 257

- Spinks, Charles N. "The Termination of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance." Pacific Historical Review 6, no. 4 (1937): 324

- Spinks, Charles N. "The Termination of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance." Pacific Historical Review 6, no. 4 (1937): 326.

- Nish, Ian H. Alliance in Decline: A Study in Anglo-Japanese Relations 1908–23. (London: The Athlone Press, 1972), 334

- Nish, Ian H. Alliance in Decline: A Study in Anglo-Japanese Relations 1908–23. (London: The Athlone Press, 1972), 337.

- Kennedy, Malcolm D. The Estrangement of Great Britain and Japan. (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969), 54

- Nish, Ian H. Alliance in Decline, 381.

- Nish, Ian H. Alliance in Decline, 354.

- Nish, Ian H. Alliance in Decline, 381

- Nish, Ian H. Alliance in Decline, 378.

- Nish, Ian H. Alliance in Decline, 383.

- Spinks, Charles N. "The Termination of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance." Pacific Historical Review 6, no. 4 (1937): 337

- Kennedy, Malcolm D. The Estrangement of Great Britain and Japan. (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1969), 56

Further reading

- Brebner, J. B. "Canada, The Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Washington Conference." Political Science Quarterly 50#1 (1935): 45–58. online

- Daniels, Gordon, Janet Hunter, Ian Nish, and David Steeds. (2003). Studies in the Anglo-Japanese Alliance (1902–1923): London School of Economics (LSE), Suntory and Toyota International Centres for Economics and Related Disciplines (STICERD) Paper No. IS/2003/443: Read Full paper (pdf) – May 2008

- Davis, Christina L. "Linkage diplomacy: economic and security bargaining in the Anglo-Japanese alliance, 1902–23." International Security 33.3 (2009): 143–179. online

- Fry, Michael G. "The North Atlantic Triangle and the Abrogation of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance." Journal of Modern History 39.1 (1967): 46–64. online

- Langer, William. The Diplomacy of Imperialism 1890–1902 (2nd ed. 1950), pp. 745–86. online free to borrow

- Lister-Hotta, Ayako, Ian Nish, and David Steeds. (2002). Anglo-Japanese Alliance: LSE STICERD Paper No. IS/2002/432: Read Full paper (pdf) – May 2008

- Lowe, Peter. Great Britain and Japan 1911–15: A Study of British Far Eastern Policy (Springer, 1969).

- Nish, Ian Hill. (1972). Alliance in Decline: A Study in Anglo-Japanese Relations 1908–23. London: Athlone Press. ISBN 978-0-485-13133-8 (cloth)

- __________. (1966). The Anglo-Japanese Alliance: The diplomacy of two island empires 1894–1907. London: Athlone Press. [reprinted by RoutledgeCurzon, London, 2004. ISBN 978-0-415-32611-7 (paper)]

- O'Brien, Phillips Payson. (2004). The Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902–1922. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-415-32611-7 cloth)

- Satow, Ernest and George Alexander Lensen. (1968). Korea and Manchuria between Russia and Japan 1895–1904: The Observations of Sir Ernest Satow, British Minister Plenipotentiary to Japan (1895–1900) and China (1900–1906). Tokyo: Sophia University Press/Tallahassee, Florida: Diplomatic Press. ASIN B0007JE7R6; ASIN: B000NP73RK

- Spinks, Charles N. "The Termination of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance." Pacific Historical Review 6#4 (1937): 321–340. online

- Steiner, Zara S. "Great Britain and the Creation of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance." Journal of Modern History 31.1 (1959): 27–36. online

External links

- Main points of the Anglo-Japanese agreements – by FirstWorldWar.com

- Text of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902 (bilingual)

- Beasley, W. G. (1962). The Modern History of Japan. Boston: Frederick A. Praeger. ASIN B000HHFAWE (cloth) – ISBN 978-0-03-037931-4 (paper)