Kantokuen

KANTOKUEN (Japanese: 関特演, from 関東軍特別演習, Kantogun Tokubetsu Enshu, "Kwantung Army Special Maneuvers"[2]) was an operational plan created by the General Staff of the Imperial Japanese Army for an invasion and occupation of the far eastern region of the Soviet Union, capitalizing on the outbreak of the Soviet-German War in June 1941. Involving seven Japanese armies as well as a major portion of the empire's naval and air forces, it would have been the largest single combined arms operation in Japanese history, and one of the largest of all time.[3]

| Kantokuen | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific War of World War II | |

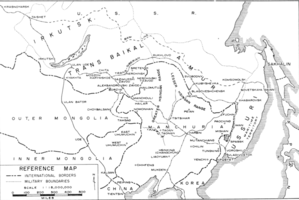

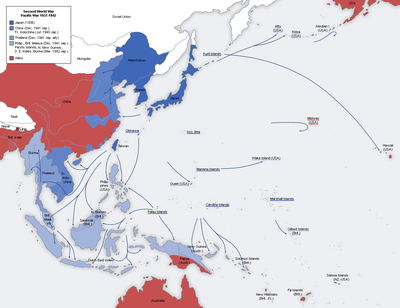

A map outlining the initial Japanese offensive moves against the USSR; the final objective was a line running along the western slope of the Greater Khingan Range. | |

| Operational scope | Strategic |

| Location | |

| Planned | September 1941[1] |

| Planned by | Japanese Imperial General Headquarters |

| Objective | Occupation of far eastern USSR |

| Outcome | Cancelled on August 9, 1941 |

The plan was approved in part by Emperor Hirohito on July 7 and involved a three-step readiness phase followed by a three-phase offensive to isolate and destroy the Soviet defenders in no more than six months.[4] It envisioned heavy use of chemical and biological weapons. [5] After growing conflict with simultaneous preparations for an offensive in Southeast Asia, together with the demands of the Second Sino-Japanese War and dimming prospects for a swift German victory in Europe, Kantokuen began to fall out of favor at Imperial General Headquarters and was eventually abandoned following increased sanctions by the United States and its allies in late July and early August 1941.[6] Nevertheless, the presence of large Japanese forces in Manchuria forced the Soviets, who had long anticipated an attack from that direction, to keep considerable military resources on standby for the duration of World War II.[7]

Background

The roots of anti-Soviet sentiment in Imperialist Japan began before the foundation of the Soviet Union. Eager to further limit Russian influence in East Asia after the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) and contain the spread of Bolshevism, the Japanese deployed some 70,000 troops into Siberia from 1918 to 1922 as part of the Siberian Intervention on the side of the White Movement, occupying Vladivostok and many key points in Far Eastern Russia east of Lake Baikal.[8][9] Following the international withdrawal from Russian territory, the Imperial Japanese Army, mindful of the potential of the USSR as a military power and keeping with the convention of Russia as a traditional enemy, made contingency plans for war with the Soviet Union. At first they were defensive, assuming an attack from the Red Army into Chinese territory which would be parried by a Japanese counter-thrust from Korea; the decisive battlefield would be in southern Manchuria.[10] Following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria and its annexation in 1931, Japanese and Soviet troops for the first time faced one another along a border thousands of kilometers long. To protect the Japanese Manchukuo puppet state and to gain the initiative, the IJA adopted a policy of halting any Soviet advance along the border and fighting the greater part of the war in Siberia – an "epoch making change" in Japanese strategic thought which led to offensive planning that would not be reversed until 1945. Over time, Japanese operational plans evolved from small operations into multi-stage offensive actions aimed first against Vladivostok and eventually the entirety of the Soviet Far East as far as Lake Baikal.[11]

1937 and beyond

Before the outbreak of Second Sino-Japanese War in July 1937, Soviet-Japanese relations began to deteriorate rapidly.[12] The Kwantung Army responsible for governing Manchuria, previously elevated from a minor garrison command to the level of a general headquarters, became increasingly bellicose towards its northerly neighbor. The army began to act as a "self-contained, autonomous" entity almost entirely independent from the central government in Tokyo. With this conduct came a corresponding rise in Soviet-Japanese border conflicts, culminating in the Kanchatzu Island Incident in which a Soviet river gunboat was sunk by Japanese shore batteries, killing 37 personnel.[13] This, other episodes, and the reciprocal political and military subversion by both sides (the Japanese recruiting White Russian agents and the Soviets sending material support to China, before and during the war with Japan) led figures on both sides to conclude that a future war was likely, even, where some in the Kwantung Army were concerned, inevitable.[14][15]

After war began between China and Japan in July 1937, Japanese options for Manchuria became very limited. The Soviets capitalized on this vulnerability by signing a non-aggression pact with China and supplying them with arms and equipment. Pravda's publication of February 13, 1938, noted that

...the Japanese Army, which possesses a strength of about 1,200,000 men, 2,000 planes, 1,800 tanks, and 4,500 heavy artillery pieces, committed about 1,000,000 troops and a greater part of its arms in China.

— Pravda[16]

The Japanese predicament did not prevent them from continuing to formulate war plans against the USSR; their operational plan of 1937, though crude and deficient from a logistical perspective, provided the basis for all subsequent developments through 1944.[17][lower-alpha 1] The plan (and most others after it) called for a sudden initial onslaught against the Soviet 'Maritime Province' facing the Pacific Ocean (also referred to as "Primorye"), coupled with holding actions in the north and west. Should the first phase meet with success, the other fronts would likewise transition to the offensive after the arrival of reinforcements.[18]

In 1936, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin began the Great Purge of opposition including the Red Army officer corps, killing or incarcerating tens of thousands of high-ranking figures, often on trumped up or fictitious charges. The Red Army's fighting power was severely weakened, an observation seemingly confirmed by its relatively poor showings at the Battle of Lake Khasan in 1938 and the Winter War against Finland in 1940.[19] Fear led people to defect or flee abroad; on June 13, 1938, Genrikh Lyushkov, Chief of the Far Eastern Department of the NKVD (Soviet secret police), crossed the border into Manchuria and turned himself in to the IJA, bringing with him a wealth of secret documents on Soviet military strengths and dispositions in the region. Lyushkov's treason was a major intelligence coup for Japan, and he continued to work against his country up until his disappearance amidst the Soviet invasion of Manchuria in August 1945.[20]

The Hachi-Go plans

Independent of their yearly planning, in 1938–39 the Operations Bureau of the Japanese Army General Staff and the Kwantung Army cooperated on a pair of related contingencies under the umbrella term "Operational Plan no. 8," or the "Hachi-Go" plan. These two schemes, designated Concepts "A" and "B," examined the possibility of an all-out war with the Soviet Union beginning in 1943.[21] Both were far larger than anything previously conceived of by the Japanese, envisioning a commitment of 50 IJA divisions against an expected 60 for the Soviets to be delivered incrementally from China and the Home Islands. Whereas Concept A followed a more traditional setup by calling for attacks in the East and North while holding in the West, Concept B examined the possibility of first striking out into the vast steppe between the Great Khingan Mountains and Lake Baikal in the hopes of scoring a knockout blow early – thus dooming the defenders of Primorye and Vladivostok to defeat in detail.[22] The scope of operations was enormous: the two forces would have fought over a frontage nearly 5,000 kilometers (3,100 miles) in length, with Japan's final objectives being up to 1,200 km (750 mi) deep into Soviet territory. In terms of distances, Concept B of Hachi-Go would have dwarfed even Barbarossa, Nazi Germany's invasion of the USSR in June 1941.[lower-alpha 2]

| Japan (50 divisions) | USSR (60 divisions) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | D-Day | D+60 | D+90 | D-Day | D+60 | D+90 |

| Eastern Front | 12 | 20 | 20 | 15 | 20 | 20 |

| Northern Front | 8 | 13 | 15 | 6 | 12 | 15 |

| Western Front | 3 | 8 | 15 | 9 | 18 | 25 |

| Divs not yet arrived | 27 | 9 | 0 | 30 | 10 | 0 |

| Japan (45 divisions) | USSR (60 divisions) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | D-Day | D+60 | D+90 | D-Day | D+60 | D+90 |

| Eastern Front | 5 | 8 | 10 | 15 | 18 | 18 |

| Northern Front | 3 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 12 | 12 |

| Western Front | 15 | 20 | 25 | 9 | 20 | 30 |

| Divs not yet arrived | 22 | 9 | 0 | 30 | 10 | 0 |

As impressive as this appeared on paper, however, the Japanese were forced to acknowledge several harsh realities blocking the implementation of Hachi-Go in the near future. Specifically with regard to Concept B, the railway network in Manchuria had not been sufficiently expanded to facilitate such a far-reaching offensive and supply stocks on hand in the country were seriously below the required levels. Furthermore, the ongoing war in China precluded the concentration of the planned 50 divisions without fatally weakening the Japanese effort there. Additionally, Imperial General Headquarters concluded that in order to sustain a drive out to Lake Baikal, a fleet of some 200,000 trucks would be necessary,[24] a number more than twice as great as anything the entire Japanese military possessed at any given time.[25] Popular support for Concept B in IJA circles dissipated in 1939 after the Battle of Khalkhin Gol demonstrated the extensive challenges of supplying a sustained military commitment on even a relatively limited scale so far away from the nearest rail heads. From that point forward, Japanese offensive planning vis-a vis the USSR was chiefly focused on the Northern and Eastern fronts, with any advances in the West being limited to relatively modest gains on the far slope of the Great Khingan range.[26]

Decision 1941

Junbi Jin and "the persimmon"

Toward the end of his life, Adolf Hitler reportedly lamented: "It is certainly regrettable that the Japanese did not enter the war against Soviet Russia alongside us. Had that happened, Stalin's armies would not now be besieging Breslau and the Soviets would not be standing in Budapest. We would together have exterminated Bolshevism before the winter of 1941."[27] From the Japanese perspective, however, Germany's attitude toward cooperation against the USSR during the 1939–41 period was one of ambivalence, even duplicity.[28] Following the defeat at Khalkhin Gol, Germany's sudden consummation of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of non-aggression with Stalin was met with shock and anger in Japan, which viewed the move as a direct violation of the Anti-Comintern Pact and a betrayal of their common interests. Consequently, in April 1941 Japan felt free to conclude its own Neutrality Pact with the Soviets, as tension with the West, particularly the United States, began to mount over the Japanese occupation of (Vichy) French Indochina the previous year. As Allied economic sanctions began to pummel Japan, the growing threat of war in the south and the sense of "tranquility" in the north tended to divert Japanese attention away from their long-planned campaign in Siberia.[29][30] The shift was particularly welcomed by the Navy, which traditionally favored a policy of Nanshin-ron (southward expansion) while maintaining a deterrent against the Soviet Union, as opposed to Hokushin-ron (northward expansion), which was favored by the Army.[31]

Hence, it was with great shock and consternation that the Japanese government met the news of Operation Barbarossa, Hitler's invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, mortified over this 'second betrayal' of Japan, even briefly considered abandoning the Tripartite Pact. On the other hand, Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka began immediately advocating for an abandonment of the Neutrality Pact with the USSR (of which he himself had been the architect), and demanded an attack in support of Germany.[32] Matsuoka's views were supported by both the Kwantung Army and the IJA General Staff, who were eager for a "quick decision."[33] Prior to the invasion, earlier in June the Japanese government had decided on a 'flexible response' policy to establish readiness in case of a need to attack either northward or southward, referred to as "Junbi Jin Taisei" ("Preparatory Formation Setup"). Under the Junbi Jin concept, intervention in the event of a Soviet-German war was contemplated, but only on the occasion that events took a favorable turn for Japan. Although it was not always so clear-cut, this philosophy ultimately defined Japanese strategic thinking throughout 1941.[34]

Junbi Jin encountered its first serious test in the form of an emergency meeting of the top Army and Navy leaders on June 24 to establish a new national policy bearing in mind the situation in the USSR. During this conference the Army vigorously argued for the use of force against Siberia, while the Navy opposed it. Eventually a compromise was reached whereby the Army would be allowed to intervene against the USSR should the circumstances permit, but with the caveat that preparations for this eventuality not interfere with concurrent planning for war in the south.[35] Although this arrangement was accepted in principle, there was still disagreement over exactly how the Army would go about resolving the "northern question," as well as the timing of such a resolution. The basic conflict can be summarized by the popular metaphor of "the persimmon," with the Army General Staff (AGS) and the Kwantung Army arguing for an offensive even if the fruit was 'still green' (i.e., even if the USSR had not suffered a catastrophic collapse against Germany), and their opponents opting for a more conservative approach, assigning less immediacy to the Manchurian front given Japan's wider strategic position.[36] From the point of view of the AGS, if Japan was going to engage in hostilities in 1941 it was imperative that the fighting be over by mid-October, bearing in mind the bitter climate of Siberia and Northern Manchuria. Because 60–70 days would be necessary to complete operational preparations and a further 6 to 8 weeks would be needed to crush the Soviets in the territory between Manchuria and the Pacific, the window of action was quite limited. In response, Army General Staff proposed a "crash schedule" for planning purposes intended to 'shave off' as much time as possible:[37]

- 28 June: Decide on mobilization

- 5 July: Issue mobilization orders

- 20 July: Begin troop concentration

- 10 August: Decide on hostilities

- 24 August: Complete readiness stance

- 29 August: Concentrate two divisions from North China in Manchuria, bringing the total to 16

- 5 September: Concentrate four further divisions from the homeland, bringing the total to 22; complete combat stance

- 10 September (at latest): Commence combat operations

- 15 October: Complete first phase of war

All in all, AGS called for 22 divisions with 850,000 men (including auxiliary units) supported by 800,000 tons of shipping to be made ready should war come with the Soviets.[38] The War Ministry as a whole, however, was not in agreement with the Army 'hawks'. Although they supported the notion of reinforcing the north, they preferred a far more modest limit of only 16 divisions between the Kwantung and Korea Armies in light of priorities elsewhere – a force that, in the opinion of the Kwantung Army, would be "impossible" to engage the Soviets with. The message was clear: Japan would wait until the persimmon ripened and fell before acting against the Red Army.[39]

KANTOKUEN

Stung by their initial setback at the hands of the War Ministry, the IJA hardliners would get their revenge, at least in principle. During a personal visit on July 5, 1941, Major General Shinichi Tanaka, AGS Operations Chief and co-leader (along with Matsuoka) of the "Strike North" faction in Tokyo, managed to persuade War Minister Hideki Tojo to support the Army General Staff's opinions concerning the 'rightness' and 'viability' of reinforcing Manchuria. General Tanaka and his supporters pushed for a greater commitment than even the Army's June 1941 plan – a total of up to 25 divisions in all – under the guise of establishing the readiness stance of only 16 divisions preferred by the War Ministry. Tanaka's plan involved two stages, a build up and readiness phase (No. 100 setup) followed by the offensive stance (Nos. 101 and 102 setups), after which the Kwantung Army would await the order to attack. The entire process was referred to by the acronym of "KANTOKUEN," from (Kantogun Tokubetsu Enshu), or Kwantung Army Special Maneuvers. With Tojo's support for Kantokuen secured, the hardliners completed their circumvention of the War Ministry on July 7, when General Hajime Sugiyama visited the Imperial Palace to request Hirohito's official sanction for the build up. After assurances from the General that the Kwantung Army would not attack on its own initiative after receiving reinforcements, the Emperor relented.[40]

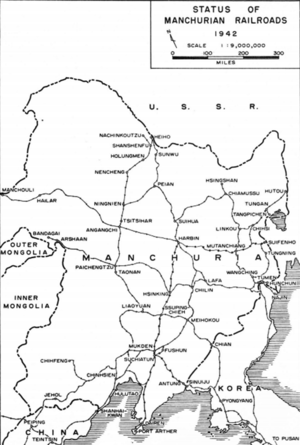

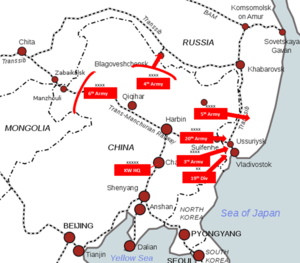

Operationally speaking, Kantokuen was essentially identical to the War Plan of 1940,[41] albeit with an abbreviated force structure (25 vs. 43 divisions) presumably banking on the Soviet inability to reinforce the Far East in light of the conflict with Germany. The level of commitment, however, was still enormous – by far the single greatest mobilization in the history of the Japanese Army.[42] In order to facilitate the operation, a tremendous quantity of both combat and logistical assets would have to be dispatched to Manchuria on top of the existing structure. In particular, to capitalize on the Japanese advantage of interior lines relative to the Soviets, the railways in the north and east would have to be expanded to accommodate the increased burden an offensive war would carry.[43] Additionally, port facilities, military housing, and hospitals were also to be augmented.[44] Like the previous concepts drawn up in the aftermath of the Nomonhan Incident, Kantokuen would begin with a massive initial blow on the Ussuri Front against Primorye, followed up with another attack to the North against Blagoveshchensk and Kuibyshevka.[45] Under the umbrella organization of the First Area Army, the Japanese Third and Twentieth Armies, supported by the 19th Division of the Korea Army, would penetrate the border south of Lake Khanka with the aim of overcoming the main Soviet defensive lines and threatening Vladivostok. Simultaneously, the Fifth Army would strike just south of Iman (present day Dalnerechensk), completing the isolation of the Maritime Province, severing the Trans-Siberian Railway, and blocking any reinforcements arriving from the north; these groupings would comprise up to 20 divisions in all, with the equivalent in smaller units of several more.[46] In northern Manchuria, the Fourth Army with four divisions would at first hold the Amur River line before transitioning to the offensive against Blagoveshchensk.[47][48] Meanwhile, two reinforced divisions of Japanese troops outside the Kantokuen force structure would commence operations against Northern Sakhalin from both the landward and seaward sides with the aim of wiping out the defenders there in a pincer movement.[49] Other second stage objectives included the capture of Khabarovsk, Komsomolsk, Skovorodino, Sovetskaya Gavan, and Nikolayevsk, while amphibious operations against Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky and other parts of the Kamchatka Peninsula were contemplated.[50][51]

To ensure the success of this, the most critical phase of the war, Kantokuen called for the application of overwhelming forces: 1,200,000 men, 35,000 trucks, 500 tanks, 400,000 horses, and 300,000 laborers in 23 to 24 divisions for the offensive on the Eastern and Northern Fronts alone.[52] This would have meant, however, that the Western Front facing Mongolia and the Trans-Baikal region could be defended by only 1 to 2 divisions plus the equivalent in Border Guards Units of a few more.[lower-alpha 3] Indeed, during the initial phase of operations the Japanese Sixth Army was allocated only the 23rd Division and the 8th Border Guards Unit, veterans of the fighting at Khalkhin Gol two years before.[54] To minimize the danger from a Soviet counteroffensive in the West while the bulk of the Japanese Army was engaged in the East, the IJA hoped that delaying actions combined with the vast expanses of the Gobi Desert[55] and Hailar Plain[56] would serve as "strategic buffers" preventing the Red Army from mounting a serious challenge to the heart of Manchuria before the main body regrouped for a pivot west. The final objective of the Japanese troops was a line running through Skovorodino and the western slopes of the Great Khingan Mountains, along which they would defeat the remaining Soviet forces and transition to a defensive stance.[57]

As in any modern military operation, air power played a crucial role in the Kantokuen Plan. Before the outbreak of the Pacific War the Japanese intended to dispatch some 1,200 to 1,800 planes in 3 air divisions to bolster the existing 600 to 900 aircraft in Manchuria,[58] which were to cooperate with about 350 Navy planes to launch a "sudden," "annihilating" attack on the Soviet Far East Air Force both in the air and on the ground at the outset of hostilities. Should they have succeeded, the Japanese air units would then have focused their efforts toward supporting the ground forces on the tactical level, cutting Soviet lines of communication and supply (particularly in the Amur and Trans-Baikal regions) and blocking air reinforcements from arriving from Europe.[59]

On the whole, Japanese and Axis forces involved in operations against the USSR from Mongolia to Sakhalin would have totalled approximately 1.5 million men,[lower-alpha 4] 40,000 trucks,[lower-alpha 5] 2,000 tanks,[lower-alpha 6] 2,100–3,100 aircraft,[62] 450,000 horses,[lower-alpha 7] and a vast quantity of artillery pieces.[lower-alpha 8]

The battlefield and theater of action

In preparing for any future war in the Far East, Japanese (and Soviet) strategic planning was dominated by two fundamental geopolitical realities:[64][65]

- 1.) The Soviet Far East and Mongolian People's Republic formed a horseshoe around Manchuria over a border more than four and a half thousand kilometers in length, and

- 2.) The Soviet Far East was economically and militarily dependent on European Russia via the single Trans-Siberian Railroad.

This second observation, perhaps even more than the first, formed the basic foundation of Far Eastern Russia (FER)'s vulnerability in a war against Japan. The Far East's population was small, only around 6 million citizens,[67] a relatively high percentage of whom were concentrated in urban rather than rural environments, suggesting an emphasis on industry.[68] Consequently, the lack of farmers meant that there would be a deficiency in food production for both civilians and soldiers as well as a smaller pool of potential reservists.[69] Despite being allocated considerable resources under Joseph Stalin's Second and Third Five Year Plans (1933–1942), serious shortcomings still remained. Although the Soviets traditionally relied on the Trans-Siberian Railway to send manpower, food, and raw materials eastward to overcome the major deficits (sometimes even forcibly resettling discharged soldiers in Siberia),[70] this created another problem whereby the limited capacity of that railroad also restricted the maximum size of any Red Army force that could be brought to bear on Japan, which the Japanese estimated would amount to the equivalent of 55 to 60 divisions.[71]

| Commodity | Requirement | Actual production | Self-sufficiency | Wartime reserves |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grain | 1,390,000 tons | 930,000 tons (excluding 200k tons for seed supply) | 67% | 800,000 tons |

| Petroleum | 1,520,000 tons | 1,000,000 tons | 66% | 1,300,000 tons |

| Steel | 580,000 tons | 220,000 tons | 38% | Unknown |

| Coal | 13,200,000 tons | 13,200,000 tons | 100% | Unknown |

| Item | Number |

|---|---|

| Aircraft | 400 |

| Tanks | 150 |

| Armored cars | 30 |

| Artillery | 550 |

Thus, any prolonged disruption of the Trans-Siberian Railway would ultimately prove fatal to both FER and any Soviet attempt to defend it, a feat rather easily managed from the Japanese side as the tracks ran parallel to the frontier for thousands of kilometers, sometimes even coming to within artillery range of the Manchurian border. Furthermore, though the encircling geography of the USSR and Mongolia were theoretically advantageous under an offensive setting by granting the Red Army the opportunity for a strategic envelopment of Manchuria (a military impossibility in 1941),[74] on the defensive the strung out Russian groupings would be vulnerable to isolation and piecemeal destruction at the hands of a more compact opponent. Although the Soviets made concerted efforts to address this vulnerability, such as beginning work on a 4,000 kilometer extension of the Trans-Siberian Railway, the BAM Line, these alone were insufficient to rectify the basic weakness.[75]

The limitations of the Trans-Siberian Railway and the remoteness of FER proved both a blessing and a curse to both sides. Although it prevented the Red Army from concentrating and supplying vast numbers of soldiers against a Japanese invasion and granted the latter an effective means of isolating the territory from European Russia, it also ensured that Japan alone could never administer a decisive defeat to the Soviet Union because the latter's main military and economic assets would remain unharmed.[76] The IJA General Staff concluded that only an offensive on two fronts, Europe and Asia, brought to bear on the USSR's vital industrial centers and aimed at collapsing its political will to resist could succeed in bringing about its destruction.[77]

Weapons of mass destruction

Since the mid-1930s, Japan invested large resources toward the creation and development of a tremendous arsenal of chemical and biological weapons, aspiring to use them as a means of inflicting mass-casualties on Chinese and Soviet opponents in the event of a war.[78] During the campaign in China, the Japanese military routinely subjected opposing population centers to ruthless attacks by these weapons of mass-destruction, resulting in the deaths of as many as 2,000,000 people.[79] Oftentimes the targets, such as the helpless city of Baoshan, possessed no military value whatsoever; clogged with refugees fleeing the front and with grossly inadequate medical infrastructure, Baoshan suffered up to 60,000 dead after being hit by Cholera bombs in 1942.[80] The war against the Soviet Union was to have been little different: after the introduction of the Kantokuen plan, Japan's Unit 731, Unit 100, and Unit 516 began making extensive preparations for similar operations in Siberia.[81]

On the initiative of the AGS 1st Operations Division, "epizootic detachments" consisting of specialists from Unit 100 were set up at each corps-level headquarters in Manchuria to increase the Kwantung Army's readiness for biological warfare. Three primary media for spreading disease were identified: direct spraying from aircraft, bacteria bombs, and saboteurs on the ground. During a war with the USSR, the Japanese planned to make use of all three, spreading plague, cholera, typhus, anthrax, and other diseases on both the opposing front lines and rear areas with the goal of infecting populated regions, livestock, crops, and water supplies. The main targets were the areas around Blagoveshchensk, Khabarovsk, Voroshilov, and Chita, and through 1942 extensive reconnaissance of the border region was conducted while detailed maps were created indicating targets of opportunity for biological warfare.[82]

The Kwantung Army, according to Colonel Asaoka of Unit 731, regarded its weapons of mass-destruction as trump cards against the Soviets which would guarantee a Japanese victory. As late as 1945, their supply was so great that even the output of that unit alone was deemed sufficient to supply the entire Japanese Army; evenly distributed and under ideal conditions, it was claimed, the Japanese bioweapon stockpile was capable of destroying all of humanity.[83]

Plans for occupation

By Imperial decree on October 1, 1940, the Total War Research Institute was established under the direct supervision of the Prime Minister. Working closely with the Research Society for the Study of State Policy (an organization that included many high-ranking Japanese government ministers and industrialists), its main goal was to create policies for the formation and rule over the planned "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere," which was to be the 'New Order' in the region.[84] Under the provisions of the Administrative Plan of December 1941, the Primorye Region would be directly annexed into the Empire and the remaining territories adjacent to Manchukuo would be subject to the latter's influence. The hypothetical delineation point between German and Japanese spheres of influence over the prostrate Soviet Union was designated as the city of Omsk.[85]

The occupation was to be managed with extraordinary brutality, typical of Japanese conduct in China and elsewhere during the war. In general, it envisioned the displacement of the native population to make room for a projected influx of Japanese, Korean, and Manchu settlers. Given instructions to use "strictly real force, without sinking to the so-called principle of moderation," the Japanese Army authorities were to annihilate the subject Soviet population with the survivors either converted into forced labor to exploit the raw materials of the region or exiled into the frozen wastelands of the north. All pre-existing institutions were to be completely abolished and the Communist ideology outlawed and replaced with Japanese propaganda. To create, if possible, a façade of self-governance, a number of former White Movement figures (including Grigory Semyonov) were hand-picked to manage puppet government positions under the Japanese.[86]

The task of setting up the framework of the occupation regime was given to the "Hata Department," later the 5th Department of the Kwantung Army.[87]

Soviet response

In the late 1930s through 1941, the USSR's strategic planning against Japan was fundamentally defensive in nature, intended primarily to preserve the sovereignty of its Far Eastern territories and the Mongolian People's Republic. The means to this end, however, would not be completely passive. Even after the German invasion and well into 1942, STAVKA advocated for an all-out defense of the border zone and heavy counterattacks all along the front, with the objective of preventing the IJA from seizing any Soviet territory and throwing them back into Manchuria. While the aggressive language used by Boris Shaposhnikov in 1938 concerning "decisive action" in northern Manchuria after a 45-day period[88] was by 1941 moderated to simply "destroying the first echelon" of invaders and "creating a situation of stability,"[89] the Red Army never totally gave up limited offensive goals. The Japanese assessed that the dearth of traversible terrain between the Manchurian border and the Pacific Ocean combined with the vulnerability of the Trans-Siberian Railway in the Amur and Primorye regions was what compelled them to take such a stance, despite investing considerable resources to fortify the area for defensive warfare.[90]

The primary entities responsible for protecting the USSR from Japanese aggression in 1941 were the Far Eastern and Trans-Baikal Fronts, under the command of Generals Iosif Apanasenko and Mikhail Kovalyov,[91][lower-alpha 9] respectively.[92][93] The Trans-Baikal Front, with nine divisions (including two armored), a mechanized brigade, and a fortified region was tasked with defending the area west of the Oldoy River near Skovorodino, while the Far Eastern Front, with 23 divisions (including three armored), four brigades (excluding antiaircraft), and 11 fortified regions guarded the land to the east, including the crucial seaport of Vladivostok. Combined, the two fronts accounted for some 650,000 men, 5,400 tanks, 3,000 aircraft, 57,000 motor vehicles, 15,000 artillery pieces, and 95,000 horses. The distribution of manpower and equipment in prewar FER was as follows[94]

| Resource | Far Eastern Front | Trans-Baikal MD | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personnel | 431,581 | 219,112 | 650,693 |

| Small arms | 713,821 | 314,658 | 1,028,389 |

| Motor vehicles | 28,865 | 28,644 | 57,329 |

| Artillery | 9,869 | 5,318 | 15,187 |

| AFVs | 3,812 | 3,451 | 7,263 |

| Aircraft | 1,950 | 1,071 | 3,021 |

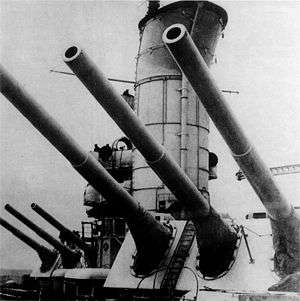

By 1942 the Vladivostok Defense Sector also possessed some 150 artillery pieces of 75 mm to 356 mm caliber, organized into 50 batteries. Of these, the most numerous was the 130 mm B-13, which made up 20 batteries (90 guns).[95][96] After the German invasion, Soviet forces in the Far East underwent a radical transformation. Even before the opening of Barbarossa, the Red Army began a steady transfer of men and materiel westward to Europe. Prior to 22 June 1941 the above figures had already been reduced by 57,000 men, 670 artillery pieces, and 1,070 tanks from five divisions;[97] between 22 June and 1 December a further 2,209 machines were sent to the front to stem the Nazi tide.[98] Additionally, during the same period 13 other divisions[99][lower-alpha 10] with 122,000 men, 2,000 guns and mortars, 1,500 tractors, and nearly 12,000 automobiles were also detached from the Far East, along with a Japanese estimate of 1,800 aircraft.[100] On the whole, between June 22, 1941 and May 9, 1945 an aggregate total of 344,676 men, 2,286 tanks, 4,757 guns and mortars, 11,903 motor vehicles, and 77,929 horses were removed from the Far Eastern and Trans-Baikal Fronts to bolster the desperate fighting against the Wehrmacht,[101] the vast majority of whom arrived before early 1943.[102]

In spite of a marked reduction in materiel power, the Soviets undertook herculean efforts to increase their troop levees in an expansion paralleling the massive Japanese build up in Manchuria, which was easily tracked by Soviet and Chinese observers thanks to its sheer size.[103] In accordance with the general mobilization ordered by the GKO on 22 July 1941, the combined strength of the Far Eastern and Trans-Baikal Fronts was to be raised to more than 1 million by 2 August.[104] By 20 December actual manpower levels totalled 1,161,202, of whom 1,129,630 were regular officers or enlisted men and the remainder were cadets or course attendees. Additionally, the number of horses increased from 94,607 to 139,150.[105] This expansion of active personnel was achieved in spite of the Far East's limited population base through the addition of reservists from the Ural, Central Asian, and Siberian Military Districts on top of those already on hand.[106] Furthermore, the standing strength of the NKVD and Soviet Navy was also augmented: between 22 June and 15 November 1941, Navy manpower in the Far East under Admiral Yumashev rose from 94,199[lower-alpha 11] to 169,029,[lower-alpha 12][107] while the NKVD border troops (with a roster of just under 34,000 before the war)[108] would, if the ratio held, have likewise increased their strength to over 60,000. Lastly there were the Mongolians, who despite their lack of heavy weaponry had earlier proved themselves against the Japanese at Khalkhin Gol and would later go on to participate in the Soviet invasion of Manchuria in August 1945. Though they lacked the experience and organization of the Soviets, their numbers came close to 80,000.[109]

On the whole, had war broken out in late August or early September 1941 the USSR and MPR would have been able to call on about 1,100,000 men, 2,000 aircraft, 3,200 tanks, 51,000 motor vehicles, 117,000 horses, and 14,000 artillery pieces from Mongolia to Sakhalin to confront the Japanese.[lower-alpha 13] Of these, approximately two thirds of all personnel (including virtually the entire navy) would be on the Amur-Ussuri-Sakhalin Front while the remainder would defend Mongolia and the Trans-Baikal region; equipment was split much more evenly between the two groupings.[110]

.jpg)

Even though the situation in Europe was dire, Soviet planners continued to adhere to essentially the same pre-war concept for operations in FER and Manchuria, as exemplified by Stavka directive Nos. 170149 and 170150 sent to Generals Apanasenko and Kovalyov on 16 March 1942.[111] Under this strategy, during the opening days of hostilities the Far Eastern Front (with its headquarters at Khabarovsk) together with the Pacific Fleet was ordered to conduct an all-out defense of the border, not allowing the Japanese onto the territory of the USSR and holding Blagoveshchensk, Iman (Dalnerechensk) and the entirety of Primorye "at all costs". The main defensive effort was to be mounted by the 1st and 25th Armies (the former based at Vladivostok) on a north-south axis between the Pacific Ocean and Lake Khanka, while the 35th Army would dig in at Iman. To the north, the 15th and 2nd Red Banner Armies, based at Birobidzhan and Blagoveshchensk, would strive to repel all Japanese assaults from the far bank of the powerful Amur River. Meanwhile, the Soviets would stand firm on Sakhalin, Kamchatka, and the Pacific Coast, while attempting to deny the Sea of Okhotsk to the IJN. To help aid this effort, the Red Army had for years undertaken a determined fortification program along the borders with Manchuria involving the construction of hundreds of hardened fighting positions backed by trenches, referred to as "Tochkas" (points).[112] There were three types of Tochkas, DOTs (permanent fire points), SOTs (disappearing fire points), and LOTs (dummy fire points). The most common form of DOT built by the Soviets in the Far East was hexagonal in shape, with an interior diameter of 5–6 m (16–20 ft) for the smaller bunkers and up to 10 m (33 ft) for larger ones. They protruded approximately two meters above ground level, with the outer wall facing the front made of solid concrete 1 m (3.3 ft) or more thick. The backbone of the Soviet defenses, DOTs usually contained two or three machine guns; some were equipped with one or two 76 mm guns. The Soviets arranged their DOTs into belts: depending on the terrain, the strongpoints were spaced out over 400–600 m (440–660 yd) intervals and positioned in two to four rows 300–1,000 m (330–1,090 yd) deep from one another; by late 1941, the Tochkas were distributed between 12 fortified regions as follows:[113]

Fortified regions in the Amur, Ussuri, and Trans-Baikal sectors

| UR Name | HQ location | Frontage (km) | Depth (km) | Number of DOTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. 113 | Chertovaya | 35 | 2–7 | 125 |

| No. 108 | Kraskino | 46 | 2–8 | 105 |

| No. 110 | Slavyanka | 45 | 1–7 | 30 |

| No. 107 | Barabash | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| No. 111 | (No nearby town) | 36 | 1–8 | 55 |

| No. 106 | Konstantinovka | 35 | 2–8 | 155 |

| No. 105 | Grodekovo | 50 | 2–12 | 255 |

| No. 109 | Iman | 35 | 1–10 | 100 |

| No. 102 | Leninskoe | 75 | 1–8 | 70 |

| No. 101 | Blagoveshchensk | 110 | 1–7 | 326 |

| Dauriya | Dauriya | 65 | 2–5 | 170 |

| Borzya | Borzya | unknown | unknown | approx. 1/sq. mile |

The Fortified Regions were well sited: since there were a limited number of roads crossing the hilly, forested frontier, the Soviets could be confident that each avenue of approach was covered by prepared defenses that would have to be overcome via costly frontal attack, delaying the enemy and forcing him to pay heavily in manpower and equipment.[114] To counter the Tochkas, the Japanese were forced to keep considerable quantities of heavy artillery near the border, ranging from more modern Type 45 240 mm howitzers and 300 mm howitzers to antiquated 28 cm Howitzer L/10 from the Russo-Japanese War. As an added precaution, in the aftermath of the Battle of Khalkhin Gol, the IJA distributed a special one-ton shell with a range of only 1,000 meters to its Type 7 30 cm Howitzers [lower-alpha 14] meant to pulverize an enemy strongpoint in a single hit.[116] Despite the advantages conferred on them by the border terrain and Tochka belt, the Red Army did not intend solely to hunker down and outlast a Japanese assault. By the fifth day of war, STAVKA ordered the troops of the 15th and 35th Armies (minus the 66th Rifle Division), together with the Amur Red Banner Military Flotilla and any available reserves to defeat the Japanese-Manchu units opposite them, force the Amur and Ussuri, and launch a counter-offensive coordinated against both sides of the Sungari River in Manchurian territory. The final objectives of the Sungari Front groups were designated as the cities of Fujin and Baoqing, to be reached on the 25th day of hostilities. The object of this attack was to stabilize the front and relieve pressure on the Ussuri Railway and Khabarovsk areas.[117] Similarly, all along the front the remaining Soviet forces would also begin short counterblows "in the tactical depth,"[118] in keeping with the Soviet doctrine that defensive action cannot be successful without the coordination of position defense and counterattack.[119] Simultaneously, on the opposite side of Manchuria, the 17th and 36th Armies of the Trans-Baikal Front (with its headquarters at Mount Shirlova in the Yablonovy Range) were ordered to hold and then counterattack after a period of three days, advancing to Lakes Buir and Hulun by the tenth day of the war.[120] Undoubtedly as a consequence of the USSR's desperate situation at the time, in both cases, East and West, reinforcements from the hinterland were relatively small: just four tank brigades, five artillery regiments, six guards mortar regiments, and five armored train divisions were pledged to assist both Fronts together.[121]

With the aim of supporting the Red Army's struggle on the ground, the Air Force and Navy were also to have an active role in opposing the Japanese invasion. In the case of the air force, the foremost objective was the destruction of enemy aircraft both in the air and on the ground, followed by tactical ground-attack missions against Japanese troops to assist the progress of the Sungari Offensive. Other objectives included the destruction of railways, bridges, and airfields in both Manchuria and Korea, as well as the interception of both troop transports and warships in the Sea of Japan in coordination with the Pacific Fleet. Strategic bombing was to be limited to a mere 30 DB-3s, to be sent in groups of 8 to 10 aircraft against targets in Tokyo, Yokosuka, Maizuru, and Ominato. Concurrently, Soviet Naval forces would strive to immediately close the mouth of the Amur, mine the Tatar Strait, and defend the Pacific Coast from any potential landing, thus freeing up the 25th Army in Primorye from coast defense duty. Submarine patrols would begin in the Yellow Sea, Sea of Okhotsk, and Sea of Japan with the aim of preventing the transport of troops from the Japanese Home Islands to the Asian Mainland, as well as disrupting their maritime communications. The Soviet submariners were ordered not to approach the Japanese coast, but rather to operate relatively close to home territory in order to protect the shores.[122]

Strengths and weaknesses of the combatants

Both of the prospective belligerents faced an array of difficulties that might have impeded the attainment of their goals. In the Japanese case, although their then four-year war in China had provided them with a wealth of combat experience, their understanding and application of concepts such as modern military logistics and massed firepower still lagged behind the Red Army. At the time of the Nomonhan Incident the IJA regarded distances of 100 kilometers as "far" and 200 trucks as "many," while Zhukov's corps of over 4,000 vehicles supplied his Army Group on a 1,400 kilometer round trip from the nearest railheads.[123] To make up for their lack of numbers and limited resources, the Japanese relied on intangible factors such as fighting spirit and elan to overcome the foe, but this alone was insufficient.[124] Although the IJA's appreciation of these 20th Century military realities improved in the months and years after the fact and the Kwantung Army's material strength was vastly upgraded during the build up of 1941,[125] their fundamental reliance on spirit to bring victory in battle never changed,[126] sometimes even at the expense of logical thinking and common sense.[127] Often, traditionalism and unwillingness to change actively impeded improvements to both technology and doctrine, to the point where those who spoke up about the matter were accused of "faintheartedness" and "insulting the Imperial Army."[128] Toward the end of the war in the Pacific the pendulum began to swing in the opposite direction, with Japanese leaders grasping at 'wonder weapons' such as jet fighters, and a so-called "death ray" in the hope of reversing their fortunes.[129]

The Soviets, on the other hand, operated under the shadow of the raging war with Germany. Although the Far Eastern and Trans-Baikal Fronts had access to a formidable array of weaponry, the demands of the fighting in Europe meant that strength was siphoned away by the week. Moreover, the state of those vehicles that remained was often mixed: prior to the beginning of transfers westward in 1941 some 660 tanks[130] and 347 aircraft[131] were inoperable due to repair needs or other causes. Because the Soviets only possessed a limited offensive capability on the Primorye and Trans-Baikal directions, they could never hope to achieve a decisive victory over the Kwantung Army, even if they succeeded in slowing or stopping them.[132] Furthermore, attacking into the teeth of a prepared enemy, especially one with his own fortified regions and heavy concentrations of troops immediately opposite the border, was "the hardest kind of offensive," requiring "overwhelming numbers and massive means of assault" to succeed,[133] neither of which the Soviets possessed.[134]

Soviet forces in the Far East were dispersed over a vast arc from Mongolia to Vladivostok. Without the ability to capitalize on this deployment by striking deep into Manchuria from multiple axes, their strength would be fatally diluted and prone to piecemeal destruction at the hands of the Japanese, who could maneuver freely on their interior lines, concentrating their power at will while the immobile Red Army was fixed in place.[135] The only saving grace for the Soviets was that the remoteness of the Far East from European Russia meant that Japan alone could never hope to deal a mortal blow to the USSR, for which the former would be reliant on Germany.[136]

Organizationally, although Soviet forces in the Far East on paper amounted to some 32 division-equivalents by December 1941,[137] they were regarded as only barely sufficient for defensive operations. Compared to a typical Japanese division, pre-war Red Army units possessed slightly less manpower, but had greater access to long-range, higher caliber artillery. After the German invasion, however, the Red Army was reorganized so that each division had scarcely half the manpower and a fraction of the firepower of either its German or Japanese counterpart. Hence, to achieve superiority on the battlefield the Soviets would have to concentrate several divisions to counter each of the opponent's.[138]

| Category | IJA type "A" division | RKKA rifle division April 1941 |

IJA type "B" division | RKKA rifle division July 1941 |

German "first wave" infantry division, June 1941 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manpower | 25,654–25,874 | 14,454 | 20,505–21,605 | 10,790 | 16,860[142] |

| Rifles | 10,000 | 12,378 | 9,000 | 10,201 | 15,550[143] |

| LMGs | 405 | 392 | 382 | 162 | 435 |

| HMGs[lower-alpha 15] | 112 | 166 | 112 | 108 | 112 |

| AT rifles | 72 | 0 | 18 | 18 | 90 |

| Light mortars | 457 | 84 | 340 | 54 | 84 |

| Medium Mortars | 0 | 54 | 0 | 18 | 54 |

| Heavy mortars | 0 | 12 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 70 mm bn guns | 36 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| 75/6 mm RG | 24 | 18 | 12 | 12 | 20 |

| 150 mm RG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 75/6 mm FG | 12 | 16 | 36 or 24 | 16 | 0 |

| 105/122 mm FG/htzr. | 24 | 32 | 0 or 12 | 8 | 36 |

| 150/152 mm FG/htzr. | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| 37–50 mm AT | 40 | 62 | 22 | 18 | 72 |

| 37 mm AA | 0 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 76 mm AA | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 12.7 mm AA | 0 | 33 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| AFVs[lower-alpha 16] | 81 | 29 | 7 | 0 | 2 |

| Trucks | 200–860[144] | 586 | 310[145] | 200 | 516 |

| Horses | 9,906[146] | 3,309 | 7,500[147] | 2,468 | 5,370 |

.jpg)

.jpg)

Lastly, the quality of both personnel and equipment in the respective armies cannot be ignored. As the Soviets drained their best, most well-trained divisions to fight in the west, the overall standard of the forces in the east correspondingly diminished, forcing the STAVKA to rely more heavily on its fortified regions in defensive operations.[148] Meanwhile, the Kwantung Army opposite them then constituted "the cream of the entire Japanese armed forces,"[149] and was receiving reinforcements by the day. A large proportion of its units were elite Type A divisions,[lower-alpha 17] many of which had seen extensive service in China. The quality of the Japanese officer corps was also very high, as many figures who would go on to have notable careers in the Pacific War including Tomoyuki Yamashita (head of the Kwantung Defense Command and later First Area Army), Isamu Yokoyama (1st Division, later 4th Army), Mitsuru Ushijima (11th Division),[151] and Tadamichi Kuribayashi (1st Cavalry Brigade, Mongolia Garrison Army)[152] held commands there. While both sides primarily relied on bolt-action rifles and light automatic weapons as the backbone of the infantry, Japanese artillery often found itself outranged by the heavy Soviet guns at Khalkhin Gol, to the point where the IJA felt compelled to move their 15 cm howitzers closer to the front in order to bring them to bear, even at the expense of cover.[153] Even though the Japanese managed to disable a considerable number of Soviet guns through counterbattery fire,[154] their lack of range at extreme distances and shortage of ammunition left them at a distinct disadvantage against the Red Army.[155]

Tanks presented a mixed picture as well: although the most modern machine available to the Kwantung Army in 1941, the Type 97 Chi-Ha, had thicker armor (up to 33 mm)[156] compared to the Soviet BT and T-26, its low-velocity 57 mm gun common to medium tanks of the era was outmatched by the long-barreled 45 mm weapons mounted on its opposite numbers, while the 37 mm gun used on the Ha-Go and Te-Ke had an effective range of less than a kilometer.[157] In general, while the "handcrafted, beautifully polished" Japanese tanks were more survivable thanks to their diesel engines (the gasoline powerplants used by the Russians were especially fireprone[158]), their lesser numbers meant that each loss was more damaging to the IJA than each destroyed "crudely finished," "expendable" BT or T-26 was to the Red Army.[159] The balance in the air would have been strongly in favor of the Japanese. Although the most modern fighter in the Soviet Air Force arsenal available in the Far East, the Polikarpov I-16, was a firm opponent of the Nakajima Ki-27,[160][lower-alpha 18] the majority of planes in-theater were considerably older. Furthermore, the Soviets had no answer to either the Mitsubishi A6M, which had been fighting in China since 1940,[161] or the high-speed Ki-21 bomber, which could fly faster and farther than its contemporary, the SB-2.[162][163] Japanese pilots were also highly experienced, with IJNAS airmen averaging roughly 700 hours of flight time by late 1941, and IJAAF aviators averaging 500. Many of these fliers had already tasted combat against China or the VVS in previous battles.[164] In comparison, German pilots received about 230 hours of flying time and Soviet pilots even less.[165]

Conclusion

Support for KANTOKUEN fades

The IJA's hostility toward the Soviet Union and Japanese imperialism in general did not exist inside a vacuum. Even as the build up stage of the Kantokuen Plan was underway, external conflicts with outside powers, one military against China and the other economic against the United States and its allies, continued to drag on. Because of this reality, the need to prepare for a potential war with the Western countries together with the demands of the fight against the resistance of the Chinese loomed large in the minds of Japanese strategic planners. By mid-July 1941 Matsuoka's continued insistence for immediate war with the USSR ended with his dismissal and replacement with Admiral Teijiro Tono as Foreign Minister, dealing a blow to the 'Strike-Northers.'[166] Further damaging the anti-Soviet cause, although General Hideki Tojo and Emperor Hirohito both supported the reinforcement of Manchuria as called for by the AGS, neither was ready to commit to hostilities. Hirohito in particular continued to express worry over the volatility of the Kwantung Army and the negative image the "special maneuvers" created abroad. These concerns were not unfounded: as late as October 1941, G-2, apprehensive over the rapid increase of Japanese strength in Manchuria, recommended the US provide direct military aid to both the Soviet and Chinese armies in an effort to check Axis expansion in the East and keep the USSR in the war against Germany.[167] Nevertheless, despite the objections of General Shunroku Hata – who opposed the weakening of his China Expeditionary Army for the sake of Manchuria – and the incoming Korea Army commander Seishiro Itagaki along with the relatively high manpower levels of the Soviet Far East forces, Chief of Staff Hajime Sugiyama was still able to persuade the monarch to reaffirm his support for the build up during an audience on 1 August.[168] Events, however, had already begun to overtake them. In response to the Japanese occupation of key points in southern French Indochina on 24 July, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, citing an "unlimited national emergency," issued an executive order freezing all of Japan's assets in the United States and controlling all trade and monetary transactions involving Japanese interests. When Britain and the Dutch government in exile followed America's example, it effectively ended all trade between Japan and those three nations.[169]

Even more calamitous, on August 1, the same day Sugiyama appeared before the Emperor, the United States further sanctioned Japan by enacting a total embargo on oil. Since US exports accounted for 80 percent of Japan's oil supply and most of the rest came from the Dutch East Indies (which also refused to sell), the Japanese war machine was virtually cut off; without replenishment it would soon collapse.[170][lower-alpha 19] The oil embargo proved to be the final nail in the coffin for Kantokuen: scarcely a week later on 9 August 1941, the Army General Staff was finally forced to bow to the War Ministry as plans for the seizure of the resource rich countries of Southeast Asia were given top priority.[172] Grounded in 'sheer opportunism,' the IJA's cherished adventure in Siberia could never compete with the grim realities of national survival. In accordance with the agreement, the Kantokuen build up was to be halted at only 16 divisions, which were to "stand guard" against any provocation, facilitate diplomacy with Stalin's government, or potentially take advantage of a sudden collapse should the opportunity present itself.[173] All in all, reinforcements to Manchuria totalled 463,000 men, 210,000 horses, and 23,000 vehicles, bringing totals there to 763,000, 253,000, and 29,000, respectively. At the same time, Korea Army was expanded by a further 55,000 men, 16,000 horses, and 650 vehicles.[174] Throughout Northeast Asia, the total number of IJA personnel stationed in territories on the periphery of Soviet Russia numbered more than 1 million.[175]

"Go South" triumphant

With Kantokuen aborted halfway and Japan plunging toward self-destruction in the Pacific, the Kwantung Army found itself in the midst of a '180-degree turn' in national policy. As a harbinger of things to come, the 51st Division was actually withdrawn from its jurisdiction in September to join the 23rd Army in China, leaving a total of 710,000 men remaining in Manchuria.[176] In the face of this, Kwantung Army still clung to the hope of a "golden opportunity" for an attack on the USSR, continuing operational preparations and examining the possibility of an offensive northward before the Spring thaw of 1942, i.e., an invasion of Siberia in the winter.[177] Although the logistical difficulties of such a move were quickly comprehended, hardliners in the Operations Division refused to hear it: when a logistics colonel complained to the Army General Staff that the Kwantung Army lacked the proper billeting to endure the bitter winter cold near the Siberian frontiers, General Tanaka, father of the Kantokuen Plan, became infuriated, yelled at the colonel not to say such "nonsensical things," and slapped him. In the aftermath of this episode, common sense prevailed, and the Kwantung Army withdrew from the borders to wait out the winter. A further 88,000 men were transferred out of Manchuria to join the impending campaign to the South, lowering the strength to 620,000 men.[178]

When Japan finally struck the Allies and launched its multistage invasion of Southeast Asia in December 1941, the weakened Kwantung Army played only a limited role. Even though most of the units dispatched south beforehand were scheduled to return to Manchuria following the successful completion of the operation, the timing of their return would hinge on the outcome of the battles with the opposing ground forces.[179] In the meantime, Kwantung Army was ordered to ensure the security of Manchuria and avoid conflict with the USSR,[180] which was itself hard-pressed as German troops neared Moscow.

After the initial phase of the Southern Offensive was brought to a successful close in the spring of 1942, IGHQ, conscious of the Kwantung Army's weakened state and with a budget increase allocating more funds for spending, decided to strengthen and re-organize its troops in Manchuria.[181] This rejuvenation of combat power in the north, while bringing the Kwantung Army closer to its past goals from an organizational standpoint, still did not reflect an intention to go to war with the USSR; indeed, logistics specialists were convinced that a full year would be needed to repair the damages of the earlier redeployments and raise capabilities to the level where a serious offensive could be undertaken.[182] Nevertheless, it was during this time that the Kwantung Army reached the absolute peak of its power, attaining a strength of 1,100,000 men and 1,500 aircraft[183] in 16 divisions, two brigades, and 23 garrison units; Korea Army added another 120,000 personnel to this figure. Though the Kwantung Army briefly benefited from this momentary 'pivot' to the north, the changing tide of the War in the Pacific would soon permanently force Japan's attention back southward. Over the next three years, Kwantung Army would go on to oversee an 'exodus' of combat units from Manchuria, setting in motion a terminal decline that would ultimately be its death knell.[184]

The end of the Kwantung Army

With the Allied counteroffensive in the Pacific both larger and earlier than expected, Japanese forces on hand in the Southern Areas were insufficient to contain its momentum. Because it lacked a real strategic reserve in the Home Islands, the IJA was forced to divert troops from the Asian mainland to bolster the Empire's crumbling frontiers.[185] After the 20th, 41st, 52nd, 51st, 32nd, 35th, and 43rd[lower-alpha 20] divisions were withdrawn from China and Korea, Japan could only count on the Kwantung Army – the last major grouping not actively involved in combat operations – as a pool of ready manpower. Although minor dispatches to the south from Manchuria had already started in 1943,[186] the first wholesale movement of divisions began in February 1944 with the transfer of the 14th and 29th Divisions to Guam and Palau, where they would later be annihilated in battle.[187]

When the US, having bypassed the fortress atoll of Truk, decided to strike directly against the Marianas and decisively defeated the IJN's counterattack in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the inner perimeter of the Japanese Empire was threatened. Having still done little to strengthen its reserves, in June and July 1944 IGHQ sent seven divisions, the 1st, 8th, 10th, 24th, 9th, 28th, and 2nd Armored, into the fray, joined by an eighth, the 23rd (veterans of the Khalkhin Gol fighting in 1939), in October. Of the above, all except the 9th, bypassed on Formosa, and the 28th, on Miyako Jima, avoided being devastated by battle, starvation, and disease during the brutal combat in the Philippines and Okinawa. The decision to reinforce Formosa was of particular consequence for Japan: recognizing that island's strategic importance with regard to the flow of vital raw materials to the mainland, Tokyo resolved at all costs to prevent it from falling into Allied hands. Thus, in December 1944 and January 1945 the 12th and 71st Divisions were ordered there from Manchuria to reinforce the two division garrison recently augmented by the Kwantung 9th Division that had arrived via Okinawa. The loss of the 9th Division was seen as nothing less than a body blow for Okinawa's 32nd Army commander, Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima, who warned: "If the 9th Division is detached and transferred, I cannot fulfil my duty of defending this island." In the end, because of the US's 'island-hopping' strategy, none of the five divisions (including three from the Kwantung Army) would ever fire a shot in anger against an American invasion and were left to wither on the vine.[188]

Even before the 71st Division departed in January 1945, Kwantung Army found itself reduced to a paltry 460,000 men in just nine remaining divisions. Not a single division was left to defend Korea, and there were just 120 operable aircraft in all of Manchuria.[189] Worse still, those divisions that stayed behind were effectively ruined by transfers of men and equipment: some infantry companies were left with only one or two officers, and entire artillery regiments completely lacked guns. Although the Kwantung Army held little illusions about its miserable state of affairs (its own "exhaustive studies" concluding that it had been weakened "far beyond estimation" and that the new divisions formed to counterbalance the withdrawals, though quickly raised, possessed only a "fraction" of the fighting power of the originals), senior leaders continued to rationalize. In an audience with Hirohito on February 26, Tojo attempted to placate the Emperor by noting that the Soviets had earlier done exactly the same thing, characterizing the strength of the Soviet Far East forces and the Kwantung Army as being "in balance."[190] The next month, with the American juggernaut at last nearing the Home Islands and with none of the multitude of new formations hastily raised in their defense to be fully ready until summer, the Kwantung Army was called on yet again as the 11th, 25th, 57th, and 1st Armored Divisions were recalled to Japan while the 111th, 120th, and 121st Divisions were sent to South Korea to pre-empt a possible Allied incursion.[191] This "hemorrhage" of equipment and manpower from what was once the most prestigious outfit in the Japanese Army only stopped on 5 April 1945, when the USSR announced that it would not renew its Neutrality Pact with Japan.[192]

As the Kwantung Army's fighting power diminished, it had to amend its operational plans against the Soviets accordingly. While the strategy for 1942 was the same as it had been in 1941,[193] by 1943 this had been abandoned in favor of only one attack – either on the Eastern Front against Primorye or in the north against Blagoveshchensk – which itself soon gave way to a holding action on all fronts, attempting to check the Red Army at the borders.[194] As the Kwantung Army continued to weaken, it became apparent that even this would be too much, and so a final operational plan was adopted on 30 May 1945 in which the IJA would only delay the Soviet advance in the border zones while beginning a fighting retreat to fortifications near the Korean border, centered around the city of Tonghua – a move that, in effect, surrendered the majority of Manchuria to the opponent as a matter of course.[195][196] Although by August 1945 Kwantung Army manpower had been boosted to 714,000[197] in 24 divisions and 12 brigades thanks to the exhaustion of local reserves, cannibalization of guards units and transfers from China, privately its officers and men were in despair.[198] Most of the new formations, staffed by the old, the infirm, civil servants, colonists, and students[199] were at barely 15% combat effectiveness[200] and heavily lacking in weapons; out of 230 serviceable combat planes, only 55 could be considered modern. It was even briefly recommended that Army Headquarters be pre-emptively evacuated from Changchun, but this was rejected on security, political, and psychological grounds.[201] After the war, colonel Saburo Hayashi admitted: "We wanted to provide a show of force. If the Russians only knew the weakness of our preparations in Manchuria, they were bound to attack us."[202]

Simultaneously, Japanese intelligence watched helplessly as Soviet strength opposite them began to soar: honoring his promise at Yalta to enter the war in the Pacific within three months of Germany's defeat, Joseph Stalin ordered the transfer from Europe to the Far East of some 403,355 crack troops, along with 2,119 tanks and assault guns, 7,137 guns and mortars, 17,374 trucks, and 36,280 horses.[203] These men and their commanders were specially picked because of past experience dealing with certain types of terrain and opposition during the war with Germany that would be beneficial for the approaching campaign.[204] By the beginning of August the IJA pegged Red Army forces in Siberia at 1,600,000, with 4,500 tanks and 6,500 aircraft in 47 division-equivalents;[205] the actual totals were 1,577,725, 3,704, and 3,446, respectively.[206][lower-alpha 21] The Soviets were very deliberate in their preparations: in order to prevent the Japanese from shifting forces to block an attack on a single axis, it was determined that only an all-axes surprise offensive would be sufficient to surround the Kwantung Army before it had a chance to withdraw into the depths of China or Korea.[208] Aware that the Japanese knew the limited capacity of the Trans-Siberian Railway would mean that preparations for an attack would not be ready until autumn and that weather conditions would also be rather unfavorable before that time, Soviet planners enlisted the help of the Allies to deliver additional supplies to facilitate an earlier offensive. Because of this, the Japanese were caught unprepared when the Soviets attacked in August.[209] Despite the impending catastrophe facing Japan on all fronts, the Kwantung Army commander, General Yamada, and his top leadership, continued to live 'in a fool's paradise.'[210] Even after the obliteration of Hiroshima on 6 August, there was no sense of crisis and special war games (expected to last for five days and attended by a number of high-ranking officers) were conducted near the borders, while Yamada flew to Dairen to dedicate a shrine. Therefore, Army Headquarters was taken by complete surprise when the Soviets launched their general offensive at midnight on August 8/9 1945.[211] Although the Japanese offered vicious resistance when they were allowed to stand and fight, such as at Mutanchiang, almost without exception they were overwhelmed and pushed back from the front. After just about a week of combat, reacting to the Soviet declaration of war and the destruction of Nagasaki by a second atomic bomb, Emperor Hirohito overrode his military and ordered the capitulation of Japan to the Allied nations in accordance with the Potsdam Declaration. After some clarifications and a second rescript reaffirming Japan's surrender, General Yamada and his staff abandoned the plan to withdraw to Tonghua, even though his command was still mostly intact; the Kwantung Army officially laid down its arms on 17 August 1945 with some sporadic clashes persisting until the end of the month.[212][lower-alpha 22] The final casualties on both sides numbered 12,031 killed and 24,425 wounded for the Soviets[215] and 21,389 killed and about 20,000 wounded for the Japanese.[216][lower-alpha 23] In the end, as Foreign Minister Shigemitsu signed the unconditional surrender of Japan aboard USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, the men of the vaunted Kantogun, having once dreamed of riding into Siberia as conquerors, instead found themselves trudging there as prisoners of war.

Notes

- Japanese planners expected that only 1,000 trucks could be made available and that the supply burden would be borne by horses and 'coolies' – laborers.

- For comparison, Barbarossa was launched over a frontage of 2,900 km (1,800 mi) with the deepest penetrations being about 1,000 km (620 mi) (Defense of Brest Fortress and Battle of Moscow).

- According to Coox and JSOM vol. I, there were no additional border guards units explicitly called up for Kantokuen; historically at the end of 1941 there were a total of 13 BGUs and 11 Garrison Units in all of Manchuria, of these five (the 8th BGU, Arshaan Guards, and 9th, 1st, and 14th IGUs) were located west of the line Tonghua – Changchun – Qiqihar.[53] Since the Japanese rated these formations as approximately brigade strength, the IJA would have a maximum of just over 5 division-equivalents for defensive warfare on the Western Front.

- 1.2 million soldiers on the Eastern Front, c. 100,000 on the Western Front, another c. 100,000 in Sakhalin and Korea, and 100,000 Manchukuoan puppet troops.[60]

- 35,000 on the Eastern Front and roughly 5,000 elsewhere

- In October 1941, G-2 intelligence estimated the Kwantung Army to include over 1,700 tanks.[61] Given the disparity between the actual state of that army and the demands of Kantokuen, a figure of over 2,000 is not unreasonable.

- 400,000 on the Eastern Front and roughly 50,000 elsewhere

- Each Japanese "Type A" division typically had 148 tube artillery pieces and 457 50 mm mortars, while the "Type B" division usually had 88 and 340, respectively.[63] In addition to these there were also a large number of independent regiments, brigades, and fortress units that would have taken part as well, each with their own organic arms, though their exact total can hardly be calculated.

- Assumed command from General P.A. Kurochkin in July 1941

- July to November 1941

- 84,324 Pacific Fleet and 9,857 Amur River Flotilla

- 154,692 Pacific Fleet and 14,337 Amur River Flotilla

- Assuming linear extrapolation of mobilization/redeployment between June and December 1941.

- When firing normal shells, the Type 7 short-barreled variant had a range of 11,750 m, while the long-barreled version could fire out to 14,800 m.[115]

- Medium MGs for the Soviets

- Japanese type A divisions had an attached tank unit of 20 light tanks, 13 tankettes or armored cars, and 48 medium tanks, while Japanese type B divisions had 7 tankettes or armored cars. Soviet rifle divisions had attached armored cars and T-38 tankettes, while German infantry divisions possessed a mixture of half-tracks and armored reconnaisannce vehicles

- Permanent divisions (Ko-Shidan), initially numbered 1–20 with the exception of the 13th, 15th, 17th, 18th, and Imperial Guards.[150] However, over the course of the war other divisions were raised to either this or to A-1 (referred to as "strengthened (modified)" by the Americans) standard.

- During the air war at Khalkhin Gol, both the Ki-27 and I-16 took about equal losses

- According to the testimony of Masanobu Tsuji, the War Ministry estimated in August that if Japan pressed forward with an invasion of the USSR under the conditions of the oil embargo the IJA would run out of fuel within 6 to 12 months.[171]

- The latter four were largely destroyed en route by US sea and air power.

- Figures are for RKKA only; including the Navy and adding self-propelled guns to the "tanks" total, the grand total was 1,747,465 personnel, 5,250 tanks and SPGs, and 5,171 aircraft.[207]

- Contrary to popular opinion, the Kwantung Army still possessed considerable fighting power. By the end of the war the IJA had about 664,000 men in Manchuria and 294,200 in Korea;[213] the USMC Official History says of the matter: "Although the Kwantung Army reeled back from Soviet blows, most of its units were still intact and it was hardly ready to be counted out of the fight. The Japanese Emperor's Imperial Rescript which ordered his troops to lay down their arms was the only thing which prevented a protracted and costly battle."[214]

- Two days after the Kwantung Army's surrender on 19 August, the total number of prisoners in Soviet custody numbered 41,199.[217]

References

- Coox p. 1045

- Coox p. 1041

- JSOM vol. I p. 147

- Cherevko p. 27

- Koshkin pp. 21–22

- Coox pp. 1046–1049

- Glantz p. 60

- Humphreys p. 25

- JSOM vol. I p. 23

- JSOM vol. I pp. 23–27

- JSOM vol. I pp. 29–31

- Coox p. 102

- Coox p. 109

- Cherevko p. 19

- Coox pp. 118–119

- JSOM vol. XIII pp. 54–55

- JSOM vol. I pp. 20–21; 75–76.

- JSOM vol. I p. 61

- Drea p. 14

- Coox pp. 123–128

- JSOM vol. I p. 105

- JSOM vol. I pp. 106–108

- JSOM vol. I, 1955

- JSOM vol. I p. 108

- USSBS p. 220

- Coox p. 91

- Mawdsley, 'Conclusion'

- Coox pp. 1035–1036

- Coox p. 1034

- JSOM vol. I p. 137

- Coox p. 1037

- Coox p. 1036

- Coox p. 1038

- Coox p. 1035

- JSOM vol. I p. 137-138

- Coox p. 1040

- Coox p. 1038

- Heinrichs ch. 5

- Coox pp. 1039–1040

- Coox pp. 1040–1041

- JSOM vol. I p. 157

- JSOM vol. I p. 147

- JSOM vol. I pp. 148–151

- Coox p. 1042

- IMTFE p. 401 Retrieved 7 September 2017

- Koshkin p. 20

- Coox pp. 1042–1043

- Koshkin p. 20

- JSOM vol. I p. 181

- IMTFE pp. 401–402 Retrieved 7 September 2017

- JSOM vol. I p. 181

- Coox p. 1172

- JM-77 p.7, p.26

- Coox p. 1043

- JSOM vol. XIII p. 33

- Coox p. 90

- JSOM vol. I p. 78

- JSOM vol. I pl 176

- JSOM vol. I pp. 87–89

- JSOM vol. I p. 190

- The Kwantung vs the Siberian Army, October 21, 1941. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- JSOM vol. I p. 177

- Soldier's Guide to the Japanese Army pp. 133–135 Retrieved 5 March 2017

- JSOM vol. XIII p. 9

- Shtemenko pp. 331–332, 336–337

- JSOM vol. I, 1955

- JSOM vol. XIII p. 17

- JSOM vol. XIII p. 18

- JSOM vol. XIII p. 19

- JSOM vol. XIII p. 19

- JSOM vol. XIII pp. 23–25

- JSOM vol. XIII pp. 21–22

- JSOM vol. XIII p. 22

- JSOM vol. XIII p. 10

- JSOM vol. XIII pp. 25–26

- JSOM vol. XIII p. 13

- JSOM vol. XIII pp. 14–15

- Koshkin p. 22

- Li p. 292

- Li p. 295

- Koshkin p. 22

- Koshkin p. 22

- Koshkin p. 22

- Koshkin p. 21

- Koshkin p. 21

- Koshkin p. 21

- Koshkin p. 21

- Shaposhnikov, 1938 www.alexanderyakovlev.org Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- Vasilevsky, March 1941 Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- JSOM vol. XIII pp. 36–37

- Biografia: Kovalyov, Mikhail Prokof'evich Retrieved 6 March 2017

- Niehorster FEF Retrieved 6 March 2017

- Niehorster TBF Retrieved 6 March 2017

- Niehorster FEF and TBMD

- Vladivostok Fortress Defenses Archived 2014-08-07 at the Wayback Machine fortress.wl.dvgu.ru Retrieved 7 March 2017

- Fortvl.ru Brief History of Vladivostok Retrieved 7 March 2017

- Glantz p. 3

- Glantz p. 42

- Glantz p. 5

- Coox p. 1055

- Cherevko p. 40

- Glantz p. 5

- Coox p. 1041

- GKO mobilization order, 22 July 1941 Retrieved 7 March 2017

- RGASPI Ф.644 оп.2 д.32 лл.166–167 sovdoc.rusarchives.ru Retrieved 7 March 2017

- GKO mobilization order, 22 July 1941 www.soldat.ru Retrieved 7 March 2017

- Zhumatiy 2006

- NKVD Border Troops, prewar Retrieved 7 March 2017

- Mongolia: a Country Study p. 235 cdn.loc.gov Retrieved 7 March 2017

- Niehorster FEF and TBMD

- Zolotarev pp. 126–130

- JSOM vol. XIII p. 101

- JSOM vol. XIII pp. 101–102, 105–106

- JSOM vol. XIII p. 103

- Taki's IJA: Type 7 30cm Howitzer Retrieved 17 March 2017

- Coox p. 1026

- Zolotarev pp.127–128

- Zolotarev p. 127

- JSOM vol. XIII 103

- Zolotarev p. 129

- Zolotarev pp. 127, 129

- Zolotarev p. 128

- Coox p. 580

- Drea pp. 89–90

- Coox pp. 1051–1052

- Drea p. 90

- Coox p. 1051

- Coox pp. 1026–1027

- USSBS Report 63 p. 71 Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- Analysis of RKKA Tanks' state on June 1, 1941 Retrieved 13 March 2017

- Niehorster FEF and TMBD

- Shtemenko p. 333

- Shtemenko p. 332

- Shtemenko p. 333

- JSOM vol. I pp. 30–31

- JSOM vol XIII p. 14

- Glantz p. 5

- TM-30-430 pp. III-1 to III-3

- TM-30-430 Figure II Retrieved 16 March 2017

- Soldier's Guide to the Japanese Army pp. 133–135

- Operation Barbarossa: TOE 1st Wave Infantry Divisions Retrieved 16 March 2017

- Askey p. 675

- TM-E-30-451 Fig. 6 Retrieved 16 March 2017

- "Regular Infantry Division (Square)" World War II Armed Forces — Orders of Battle and Organizations. Retrieved 16 March 2017

- Pacific War Encyclopedia: Division Retrieved 16 March 2016

- Handbook on IJA Fig. 16 Retrieved 16 March 2017

- War Department (1 October 1944), Handbook on Japanese Military Forces, Fig. 15, TM-E 38-480, retrieved 16 March 2017 – via Hyperwar Foundation

- Glantz p. 4

- Giangreco p. 9

- AH.com: IJA Divisions, an Overview Retrieved 16 March 2017

- Coox pp. 1127–1128