National Diet

The National Diet (国会, Kokkai)[1][2] is the supreme organ of Sovereignty and the bicameral legislature of Japan consisting of the House of Representatives (衆議院, Shūgiin) and the House of Councillors (参議院, Sangiin). Both houses of the Diet are directly elected under parallel voting systems. In addition to passing laws, the Diet is formally responsible for selecting the Prime Minister. The Diet was first convened as the Imperial Diet in 1889 as a result of adopting the Meiji Constitution. It took its current form in 1947 upon the adoption of the post-war constitution. The two houses meet in the National Diet Building (国会議事堂, Kokkai-gijidō) in Nagatachō, Chiyoda, Tokyo.

National Diet 国会 Kokkai | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses | |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

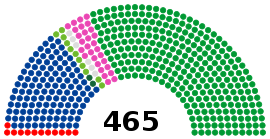

| Seats | 710

|

| |

House of Councillors political groups | Government (141)

Opposition (104)

|

| |

House of Representatives political groups | Government (313)

Opposition (151) |

| Elections | |

House of Councillors last election | 21 July 2019 (25th) |

House of Representatives last election | 22 October 2017 (48th) |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| National Diet Building, Nagatachō, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo | |

| Website | |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Japan |

|

|

|

|

Composition

The houses of the Diet are both elected under parallel voting systems. This means that the seats to be filled in any given election are divided into two groups, each elected by a different method; the main difference between the houses is in the sizes of the two groups and how they are elected. Voters are also asked to cast two votes: one for an individual candidate in a constituency, and one for a party list. Any national of Japan at least 18 years of age may vote in these elections, reduced from age 20 in 2016.[3][4] Japan's parallel voting system is not to be confused with the Additional Member System used in many other nations. The Constitution of Japan does not specify the number of members of each house of the Diet, the voting system, or the necessary qualifications of those who may vote or be returned in parliamentary elections, thus allowing all of these things to be determined by law. However it does guarantee universal adult suffrage and a secret ballot. It also insists that the electoral law must not discriminate in terms of "race, creed, sex, social status, family origin, education, property or income".[5]

Generally, the election of Diet members is controlled by statutes passed by the Diet. This is a source of contention concerning re-apportionment of prefectures' seats in response to changes of population distribution. For example, the Liberal Democratic Party had controlled Japan for most of its post-war history, and it gained much of its support from rural areas. During the post-war era, large numbers of people were relocating to the urban centers in the seeking of wealth; though some re-apportionments have been made to the number of each prefecture's assigned seats in the Diet, rural areas generally have more representation than do urban areas.[6] The Supreme Court of Japan began exercising judicial review of apportionment laws following the Kurokawa decision of 1976, invalidating an election in which one district in Hyōgo Prefecture received five times the representation of another district in Osaka Prefecture.[7] In recent elections the malapportionment ratio amounted to 4.8 in the House of Councillors (census 2005: Ōsaka/Tottori;[8] election 2007: Kanagawa/Tottori[9]) and 2.3 in the House of Representatives (election 2009: Chiba 4/Kōchi 3).[10]

Candidates for the lower house must be 25 years old or older and 30 years or older for the upper house. All candidates must be Japanese nationals. Under Article 49 of Japan's Constitution, Diet members are paid about ¥1.3 million a month in salary. Each lawmaker is entitled to employ three secretaries with taxpayer funds, free Shinkansen tickets, and four round-trip airplane tickets a month to enable them to travel back and forth to their home districts.[11]

Powers

Article 41 of the Constitution describes the National Diet as "the highest organ of State power" and "the sole law-making organ of the State". This statement is in forceful contrast to the Meiji Constitution, which described the Emperor as the one who exercised legislative power with the consent of the Diet. The Diet's responsibilities include not only the making of laws but also the approval of the annual national budget that the government submits and the ratification of treaties. It can also initiate draft constitutional amendments, which, if approved, must be presented to the people in a referendum. The Diet may conduct "investigations in relation to government" (Article 62).

The Prime Minister must be designated by Diet resolution, establishing the principle of legislative supremacy over executive government agencies (Article 67). The government can also be dissolved by the Diet if it passes a motion of no confidence introduced by fifty members of the House of Representatives. Government officials, including the Prime Minister and Cabinet members, are required to appear before Diet investigative committees and answer inquiries. The Diet also has the power to impeach judges convicted of criminal or irregular conduct.[5]

In most circumstances, in order to become law a bill must be first passed by both houses of the Diet and then promulgated by the Emperor. This role of the Emperor is similar to the Royal Assent in some other nations; however, the Emperor cannot refuse to promulgate a law and therefore his legislative role is merely a formality.[12]

The House of Representatives is the more powerful chamber of the Diet.[13] While the House of Representatives cannot usually overrule the House of Councillors on a bill, the House of Councillors can only delay the adoption of a budget or a treaty that has been approved by the House of Representatives, and the House of Councillors has almost no power at all to prevent the lower house from selecting any Prime Minister it wishes. Furthermore, once appointed it is the confidence of the House of Representatives alone that the Prime Minister must enjoy in order to continue in office. The House of Representatives can overrule the upper house in the following circumstances:[14]

- If a bill is adopted by the House of Representatives and then either rejected, amended or not approved within 60 days by the House of Councillors, then the bill will become law if again adopted by the House of Representatives by a majority of at least two-thirds of members present.[15]

- If both houses cannot agree on a budget or a treaty, even through the appointment of a joint committee of the Diet, or if the House of Councillors fails to take final action on a proposed budget or treaty within 30 days of its approval by the House of Representatives, then the decision of the lower house is deemed to be that of the Diet.[15]

- If both houses cannot agree on a candidate for Prime Minister, even through a joint committee, or if the House of Councillors fails to designate a candidate within 10 days of House of Representatives' decision, then the nominee of the lower house is deemed to be that of the Diet.

- Diet Building Interior

House of Representatives

House of Representatives House of Councillors

House of Councillors The waiting room adjacent to the Cabinet Room at the National Diet Building

The waiting room adjacent to the Cabinet Room at the National Diet Building

Activities

Under the Constitution, at least one session of the Diet must be convened each year. Technically, only the House of Representatives is dissolved before an election. But, while the lower house is in dissolution, the House of Councillors is usually "closed". The Emperor both convokes the Diet and dissolves the House of Representatives but in doing so must act on the advice of the Cabinet. In an emergency the Cabinet can convoke the Diet for an extraordinary session, and an extraordinary session may be requested by one-quarter of the members of either house.[16] At the beginning of each parliamentary session, the Emperor reads a special speech from his throne in the chamber of the House of Councillors.[17]

The presence of one-third of the membership of either house constitutes a quorum[16] and deliberations are in public unless at least two-thirds of those present agree otherwise. Each house elects its own presiding officer who casts the deciding vote in the event of a tie. The Diet has parliamentary immunity. Members of each house have certain protections against arrest while the Diet is in session and arrested members must be released during the term of the session if the House demands. They are immune outside the house for words spoken and votes cast in the House. [18] [19] Each house of the Diet determines its own standing orders and has responsibility for disciplining its own members. A member may be expelled, but only by a two-thirds majority vote. Every member of the Cabinet has the right to appear in either house of the Diet for the purpose of speaking on bills, and each house has the right to compel the appearance of Cabinet members. [20]

Legislative process

The vast majority of bills are submitted to the Diet by the Cabinet.[21] Bills are usually drafted by the relevant ministry, sometimes with the advisory of an external committee if the issue is sufficiently important or neutrality is necessary.[22] Such advisory committees may include university professors, trade union representatives, industry representatives, and local governors and mayors, and invariably include retired officials.[21] Such draft bills would be sent to the Cabinet Legislation Bureau of the government, as well as to the ruling party.[21]

History

Japan's first modern legislature was the Imperial Diet (帝国議会, Teikoku-gikai) established by the Meiji Constitution in force from 1889 to 1947. The Meiji Constitution was adopted on February 11, 1889, and the Imperial Diet first met on November 29, 1890, when the document entered into force.[23] The first Imperial Diet of 1890 was plagued by controversy and political tensions. The Prime Minister of Japan at that time was General Count Yamagata Aritomo, who entered into a confrontation with the legislative body over military funding. During this time, there were many critics of the army who derided the Meiji slogan of "rich country, strong military" as in effect producing a poor county (albeit with a strong military). They advocated for infrastructure projects and lower taxes instead and felt their interests were not being served by high levels of military spending. As a result of these early conflicts, public opinion of politicians was not favorable.[24]

The Imperial Diet consisted of a House of Representatives and a House of Peers (貴族院, Kizoku-in). The House of Representatives was directly elected, if on a limited franchise; universal adult male suffrage was introduced in 1925. The House of Peers, much like the British House of Lords, consisted of high-ranking nobles.[25]

The word diet derives from Latin and was a common name for an assembly in medieval European polities like the Holy Roman Empire. The Meiji Constitution was largely based on the form of constitutional monarchy found in nineteenth century Prussia and the new Diet was modeled partly on the German Reichstag and partly on the British Westminster system. Unlike the post-war constitution, the Meiji constitution granted a real political role to the Emperor, although in practice the Emperor's powers were largely directed by a group of oligarchs called the genrō or elder statesmen.[26]

To become law or bill, a constitutional amendment had to have the assent of both the Diet and the Emperor. This meant that while the Emperor could no longer legislate by decree he still had a veto over the Diet. The Emperor also had complete freedom in choosing the Prime Minister and the Cabinet, and so, under the Meiji Constitution, Prime Ministers often were not chosen from and did not enjoy the confidence of the Diet.[25] The Imperial Diet was also limited in its control over the budget. However, the Diet could veto the annual budget, if no budget was approved the budget of the previous year continued in force. This changed with the new constitution after World War II.

The proportional representation system for the House of Councillors, introduced in 1982, was the first major electoral reform under the post-war constitution. Instead of choosing national constituency candidates as individuals, as had previously been the case, voters cast ballots for parties. Individual councillors, listed officially by the parties before the election, are selected on the basis of the parties' proportions of the total national constituency vote.[27] The system was introduced to reduce the excessive money spent by candidates for the national constituencies. Critics charged, however, that this new system benefited the two largest parties, the LDP and the Japan Socialist Party (now Social Democratic Party), which in fact had sponsored the reform.[28]

- Diet Buildings

The First Japanese Diet Hall (1890–91).

The First Japanese Diet Hall (1890–91)..jpg) National Diet Hiroshima Temporary Building (1894).

National Diet Hiroshima Temporary Building (1894). The Second Japanese Diet Hall (1891–1925).

The Second Japanese Diet Hall (1891–1925). National Diet Building (1930).

National Diet Building (1930). National Diet Building (2017).

National Diet Building (2017).

List of sessions

There are three types of sessions of the National Diet:[29]

- R – jōkai (常会), regular, annual sessions of the National Diet, often shortened to "regular National Diet" (tsūjō Kokkai). These are nowadays usually called in January, they last for 150 days and can be extended once.

- E – rinjikai (臨時会), extraordinary sessions of the National Diet, often shortened to "extraordinary National Diet" (rinji Kokkai). These are often called in autumn, or in the summer after a regular election of the House of Councillors or after a full-term general election of the House of Representatives. Its length is negotiated between the two houses, it can be extended twice.

- S – tokubetsukai (特別会), special sessions of the National Diet, often shortened to "special National Diet" (tokubetsu Kokkai). They are called only after a dissolution and early general election of the House of Representatives. Because the cabinet must resign after a House of Representatives election, the Diet always chooses a prime minister-designate in a special session (but inversely, not all PM elections take place in a special Diet). A special session can be extended twice.

HCES – There is a fourth type of legislative session: If the House of Representatives is dissolved, a National Diet cannot be convened. In urgent cases, the cabinet may invoke an emergency session (緊急集会, kinkyū shūkai) of the House of Councillors to take provisional decisions for the whole Diet. As soon as the whole National Diet convenes again, these decisions must be confirmed by the House of Representatives or become ineffective. Such emergency sessions have been called twice in history, in 1952 and 1953.[30]

Any session of the Diet may be cut short by a dissolution of the House of Representatives. In the table, this is listed simply as "(dissolution)"; the House of Councillors or the National Diet as such cannot be dissolved.

| Diet | Type | Opened | Closed | Length in days (originally scheduled+extension[s]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | S | May 20, 1947 | December 9, 1947 | 204 (50+154) |

| 2nd | R | December 10, 1947 | July 5, 1948 | 209 (150+59) |

| 3rd | E | October 11, 1948 | November 30, 1948 | 51 (30+21) |

| 4th | R | December 1, 1948 | December 23, 1948 (dissolution) | 23 (150) |

| 5th | S | February 11, 1949 | May 31, 1949 | 110 (70+40) |

| 6th | E | October 25, 1949 | December 3, 1949 | 40 (30+10) |

| 7th | R | December 4, 1949 | May 2, 1950 | 150 |

| 8th | E | July 21, 1950 | July 31, 1950 | 20 |

| 9th | E | November 21, 1950 | December 9, 1950 | 19 (18+1) |

| 10th | R | December 10, 1950 | June 5, 1951 | 178 (150+28) |

| 11th | E | August 16, 1951 | August 18, 1951 | 3 |

| 12th | E | October 10, 1951 | November 30, 1951 | 52 (40+12) |

| 13th | R | December 10, 1951 | July 31, 1952 | 225 (150+85) |

| 14th (ja) | R | August 26, 1952 | August 28, 1952 (dissolution) | 3 (150) |

| – | [HCES] | August 31, 1952 | August 31, 1952 | [1] |

| 15th (ja) | S | October 24, 1952 | March 14, 1953 (dissolution) | 142 (60+99) |

| – | [HCES] | March 18, 1953 | March 20, 1953 | [3] |

| 16th | S | May 18, 1953 | August 10, 1953 | 85 (75+10) |

| 17th | E | October 29, 1953 | November 7, 1953 | 10 (7+3) |

| 18th | E | November 30, 1953 | December 8, 1953 | 9 |

| 19th | R | December 10, 1953 | June 15, 1957 | 188 (150+38) |

| 20th | E | November 30, 1954 | December 9, 1954 | 10 (9+1) |

| 21st | R | December 10, 1954 | January 24, 1955 (dissolution) | 46 (150) |

| 22nd | S | March 18, 1955 | July 30, 1955 | 135 (105+30) |

| 23rd | E | November 22, 1955 | December 16, 1955 | 25 |

| 24th | R | December 20, 1955 | June 3, 1956 | 167 (150+17) |

| 25th | E | November 12, 1956 | December 13, 1956 | 32 (25+7) |

| 26th | R | December 20, 1956 | May 19, 1957 | 151 (150+1) |

| 27th | E | November 1, 1957 | November 14, 1957 | 14 (12+2) |

| 28th | R | December 20, 1957 | April 25, 1958 (dissolution) | 127 (150) |

| 29th | S | June 10, 1958 | July 8, 1958 | 29 (25+4) |

| 30th | E | September 29, 1958 | December 7, 1958 | 70 (40+30) |

| 31st | R | December 10, 1958 | May 2, 1959 | 144 |

| 32nd | E | June 22, 1959 | July 3, 1959 | 12 |

| 33rd | E | October 26, 1959 | December 27, 1959 | 63 (60+13) |

| 34th | R | December 29, 1959 | July 15, 1960 | 200 (150+50) |

| 35th | E | July 18, 1960 | July 22, 1960 | 5 |

| 36th | E | October 17, 1960 | October 24, 1960 (dissolution) | 8 (10) |

| 37th | S | December 5, 1960 | December 22, 1960 | 18 |

| 38th | R | December 26, 1960 | June 8, 1961 | 165 (150+15) |

| 39th | E | September 25, 1961 | October 31, 1961 | 37 |

| 40th | R | December 9, 1961 | May 7, 1962 | 150 |

| 41st | E | August 4, 1962 | September 2, 1962 | 30 |

| 42nd | E | December 8, 1962 | December 23, 1962 | 16 (12+4) |

| 43rd | R | December 24, 1962 | July 6, 1963 | 195 (150+45) |

| 44th | E | October 15, 1963 | October 23, 1963 (dissolution) | 9 (30) |

| 45th | S | December 4, 1963 | December 18, 1963 | 15 |

| 46th | R | December 20, 1963 | June 26, 1964 | 190 (150+40) |

| 47th | E | November 9, 1964 | December 18, 1964 | 40 |

| 48th | R | December 21, 1964 | June 1, 1965 | 163 (150+13) |

| 49th | E | July 22, 1965 | August 11, 1965 | 21 |

| 50th | E | October 5, 1965 | December 13, 1965 | 70 |

| 51st | R | December 20, 1965 | June 27, 1966 | 190 (150+40) |

| 52nd | E | July 11, 1966 | July 30, 1966 | 20 |

| 53rd | E | November 30, 1966 | December 20, 1966 | 21 |

| 54th (ja) | R | December 27, 1966 | December 27, 1966 (dissolution) | 1 (150) |

| 55th | S | February 15, 1967 | July 21, 1967 | 157 (136+21) |

| 56th | E | July 27, 1967 | August 18, 1967 | 23 (15+8) |

| 57th | E | December 4, 1967 | December 23, 1967 | 20 |

| 58th | R | December 27, 1967 | June 3, 1968 | 160 (150+10) |

| 59th | E | August 1, 1968 | August 10, 1968 | 10 |

| 60th | E | December 10, 1968 | December 21, 1968 | 12 |

| 61st | R | December 27, 1968 | August 5, 1969 | 222 (150+72) |

| 62nd | E | November 29, 1969 | December 2, 1969 (dissolution) | 4 (14) |

| 63rd | S | January 14, 1970 | May 13, 1970 | 120 |

| 64th (ja) | E | November 24, 1970 | December 18, 1970 | 25 |

| 65th | R | December 26, 1970 | May 24, 1971 | 150 |

| 66th | E | July 14, 1971 | July 24, 1971 | 11 |

| 67th | E | October 16, 1971 | December 27, 1971 | 73 (70+3) |

| 68th | R | December 29, 1971 | June 16, 1972 | 171 (150+21) |

| 69th | E | July 6, 1972 | July 12, 1972 | 7 |

| 70th | E | October 27, 1972 | November 13, 1972 (dissolution) | 18 (21) |

| 71st (ja) | S | December 22, 1972 | September 27, 1973 | 280 (150+130) |

| 72nd | R | December 1, 1973 | June 3, 1974 | 185 (150+35) |

| 73rd | E | July 24, 1974 | July 31, 1974 | 8 |

| 74th | E | December 9, 1974 | December 25, 1974 | 17 |

| 75th | R | December 27, 1974 | July 4, 1975 | 190 (150+40) |

| 76th | E | September 11, 1975 | December 25, 1975 | 106 (75+31) |

| 77th | R | December 27, 1975 | May 24, 1976 | 150 |

| 78th | E | September 16, 1976 | November 4, 1976 | 50 |

| 79th | E | December 24, 1976 | December 28, 1976 | 5 |

| 80th | R | December 30, 1976 | June 9, 1977 | 162 (150+12) |

| 81st | E | July 27, 1977 | August 3, 1977 | 8 |

| 82nd | E | September 29, 1977 | November 25, 1977 | 58 (40+18) |

| 83rd | E | December 7, 1977 | December 10, 1977 | 4 |

| 84th | R | December 19, 1977 | June 16, 1978 | 180 (150+30) |

| 85th | E | September 18, 1978 | October 21, 1978 | 34 |

| 86th | E | December 6, 1978 | December 12, 1978 | 7 |

| 87th | R | December 22, 1978 | June 14, 1979 | 175 (150+25) |

| 88th | E | August 30, 1979 | September 7, 1979 (dissolution) | 9 (30) |

| 89th | S | October 30, 1979 | November 16, 1979 | 18 |

| 90th | E | November 26, 1979 | December 11, 1979 | 16 |

| 91st | R | December 21, 1979 | May 19, 1980 (dissolution) | 151 (150+9) |

| 92nd | S | July 17, 1980 | July 26, 1980 | 10 |

| 93rd | E | September 29, 1980 | November 29, 1980 | 62 (50+12) |

| 94th | R | December 22, 1980 | June 6, 1981 | 167 (150+17) |

| 95th | E | September 27, 1981 | November 28, 1981 | 66 (55+11) |

| 96th (ja) | R | December 21, 1981 | August 21, 1982 | 244 (150+94) |

| 97th | E | November 26, 1982 | December 25, 1982 | 30 (25+5) |

| 98th | R | December 28, 1982 | May 26, 1983 | 150 |

| 99th | E | July 18, 1983 | July 23, 1983 | 6 |

| 100th | E | September 8, 1983 | November 28, 1983 (dissolution) | 82 (70+12) |

| 101st | S | December 26, 1983 | August 8, 1984 | 227 (150+77) |

| 102nd | R | December 1, 1984 | June 25, 1985 | 207 (150+57) |

| 103rd | E | October 14, 1985 | December 21, 1985 | 69 (62+7) |

| 104th | R | December 24, 1985 | May 22, 1986 | 150 |

| 105th (ja) | E | June 2, 1986 | June 2, 1986 (dissolution) | 1 |

| 106th | S | July 22, 1986 | July 25, 1986 | 4 |

| 107th | E | September 11, 1986 | July 25, 1986 | 4 |

| 108th | R | December 29, 1986 | May 27, 1987 | 150 |

| 109th | E | July 6, 1987 | September 19, 1987 | 76 (65+11) |

| 110th | E | November 6, 1987 | November 11, 1987 | 6 |

| 111th | E | November 27, 1987 | December 12, 1987 | 16 |

| 112th | R | December 28, 1987 | May 25, 1988 | 150 |

| 113th | E | July 19, 1988 | December 28, 1988 | 163 (70+93) |

| 114th | R | December 30, 1988 | June 22, 1989 | 175 (150+25) |

| 115th | E | August 7, 1989 | August 12, 1989 | 6 |

| 116th | E | September 28, 1989 | December 16, 1989 | 80 |

| 117th | R | December 25, 1989 | January 24, 1990 (dissolution) | 31 (150) |

| 118th | S | February 27, 1990 | June 26, 1990 | 120 |

| 119th | E | October 12, 1990 | November 10, 1990 | 30 |

| 120th | R | December 10, 1990 | May 8, 1991 | 150 |

| 121st | E | August 5, 1991 | October 4, 1991 | 61 |

| 122nd | E | November 5, 1991 | December 21, 1991 | 47 (36+11) |

| 123rd | R | January 24, 1992 | June 21, 1992 | 150 |

| 124th | E | August 7, 1992 | August 11, 1992 | 5 |

| 125th | E | October 30, 1992 | December 10, 1992 | 42 (40+2) |

| 126th | R | January 22, 1993 | June 18, 1993 (dissolution) | 148 (150) |

| 127th | S | August 5, 1993 | August 28, 1993 | 24 (10+14) |

| 128th | E | September 17, 1993 | January 29, 1994 | 135 (90+45) |

| 129th | R | January 31, 1994 | June 29, 1994 | 150 |

| 130th | E | July 18, 1994 | July 22, 1994 | 5 |

| 131st | E | September 30, 1994 | December 9, 1994 | 71 (65+6) |

| 132nd | R | January 20, 1995 | June 18, 1995 | 150 |

| 133rd | E | August 4, 1995 | August 8, 1995 | 5 |

| 134th | E | September 29, 1995 | December 15, 1995 | 78 (46+32) |

| 135th | E | January 11, 1996 | January 13, 1996 | 3 |

| 136th (ja) | R | January 22, 1996 | June 19, 1996 | 150 |

| 137th | E | September 27, 1996 | September 27, 1996 (dissolution) | 1 |

| 138th | S | November 7, 1996 | November 12, 1996 | 6 |

| 139th | E | November 29, 1996 | December 18, 1996 | 20 |

| 140th | R | January 20, 1997 | June 18, 1997 | 150 |

| 141st | E | September 29, 1997 | December 12, 1997 | 75 |

| 142nd | R | January 12, 1998 | June 18, 1998 | 158 (150+8) |

| 143rd (ja) | E | July 30, 1998 | October 16, 1998 | 79 (70+9) |

| 144th | E | November 27, 1998 | December 14, 1998 | 18 |

| 145th | R | January 19, 1999 | August 13, 1999 | 207 (150+57) |

| 146th | E | October 29, 1999 | December 15, 1999 | 48 |

| 147th | R | January 20, 2000 | June 2, 2000 (dissolution) | 135 (150) |

| 148th (ja) | S | July 4, 2000 | July 6, 2000 | 3 |

| 149th | E | July 28, 2000 | August 9, 2000 | 13 |

| 150th | E | September 21, 2000 | December 1, 2000 | 72 |

| 151st | R | January 31, 2001 | June 29, 2001 | 150 |

| 152nd | E | August 7, 2001 | August 10, 2001 | 4 |

| 153rd | E | September 27, 2001 | December 7, 2001 | 72 |

| 154th | R | January 21, 2002 | July 31, 2002 | 192 (150+42) |

| 155th | E | October 18, 2002 | December 13, 2002 | 57 |

| 156th | R | January 20, 2003 | July 28, 2003 | 190 (150+40) |

| 157th | E | September 29, 2003 | October 10, 2003 (dissolution) | 15 (36) |

| 158th | S | November 19, 2003 | November 27, 2003 | 9 |

| 159th | R | January 19, 2004 | June 16, 2004 | 150 |

| 160th | E | July 30, 2004 | August 6, 2004 | 8 |

| 161st | E | October 12, 2004 | December 3, 2004 | 53 |

| 162nd | R | January 21, 2005 | August 8, 2005 (dissolution) | 200 (150+55) |

| 163rd (ja) | S | September 21, 2005 | November 1, 2005 | 42 |

| 164th (ja) | R | January 20, 2006 | June 18, 2006 | 150 |

| 165th (ja) | S | September 26, 2006 | December 19, 2006 | 85 (81+4) |

| 166th (ja) | R | January 25, 2007 | July 5, 2007 | 162 (150+12) |

| 167th (ja) | E | August 7, 2007 | August 10, 2007 | 4 |

| 168th (ja) | E | September 10, 2007 | January 15, 2008 | 128 (62+66) |

| 169th (ja) | R | January 18, 2008 | June 21, 2008 | 156 (150+6) |

| 170th (ja) | E | September 24, 2008 | December 25, 2008 | 93 (68+25) |

| 171st (ja) | R | January 5, 2009 | July 21, 2009 (dissolution) | 198 (150+55) |

| 172nd (ja) | S | September 16, 2009 | September 19, 2009 | 4 |

| 173rd (ja) | E | October 26, 2009 | December 4, 2009 | 40 (36+4) |

| 174th (ja) | R | January 18, 2010 | June 16, 2010 | 150 |

| 175th (ja) | E | July 30, 2010 | August 6, 2010 | 8 |

| 176th (ja) | E | October 1, 2010 | December 3, 2010 | 64 |

| 177th (ja) | R | January 24, 2011 | August 31, 2011 | 220 (150+70) |

| 178th (ja) | E | September 13, 2011 | September 30, 2011 | 18 (4+14) |

| 179th (ja) | E | October 20, 2011 | December 9, 2011 | 51 |

| 180th (ja) | R | January 24, 2012 | September 8, 2012 | 229 (150+79) |

| 181st (ja) | E | October 29, 2012 | November 16, 2012 (dissolution) | 19 (33) |

| 182nd (ja) | S | December 26, 2012 | December 28, 2012 | 3 |

| 183rd (ja) | R | January 28, 2013 | June 26, 2013 | 150 |

| 184th (ja) | E | August 2, 2013 | August 7, 2013 | 6 |

| 185th (ja) | E | October 15, 2013 | December 8, 2013 | 55 (53+2) |

| 186th (ja) | R | January 24, 2014 | June 22, 2014 | 150 |

| 187th (ja) | E | September 29, 2014 | November 21, 2014 (dissolution) | 54 (63) |

| 188th (ja) | S | December 24, 2014 | December 26, 2014 | 3 |

| 189th (ja) | R | January 26, 2015 | September 27, 2015 | 245 (150+95) |

| 190th (ja) | R | January 4, 2016 | June 1, 2016 | 150 |

| 191st (ja) | E | August 1, 2016 | August 3, 2016 | 3 |

| 192nd (ja) | E | September 26, 2016 | December 17, 2016 | 83 (66+17) |

| 193rd (ja) | R | January 20, 2017 | June 18, 2017 | 150 |

| 194th (ja) | E | September 28, 2017 | September 28, 2017 (dissolution) | 1 |

| 195th (ja) | S | November 1, 2017 | December 9, 2017 | 39 |

| 196th (ja) | R | January 22, 2018 | July 22, 2018 | 182 (150+32) |

| 197th (ja) | E | October 24, 2018 | December 10, 2018 | 48 |

| 198th (ja) | R | January 28, 2019 | June 26, 2019 | 150 |

| 199th (ja) | E | August 1, 2019 | August 5, 2019 | 5 |

| 200th (ja) | E | October 4, 2019 | December 9, 2019 | 67 |

See also

- Bicameralism

- Government of Japan

- History of Japan

- National Diet Building

- National Diet Library

- Parliamentary system

- Politics of Japan

- List of legislatures by country

- ja:国会開会式 - Opening ceremony of National Diet.

References

- "House of Councillors The National Diet of Japan". www.sangiin.go.jp. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- "Diet functions". www.shugiin.go.jp. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- "Diet enacts law lowering voting age to 18 from 20". The Japan Times.

- Japan Guide Coming of Age (seijin no hi) Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- National Diet Library. Constitution of Japan. Published 1947. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- U.S. Library of Congress Country Studies Japan – Electoral System. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- Goodman, Carl F. (Summer 2001). "The Somewhat Less Reluctant Litigant: Japan's Changing View towards Civil Litigation". Law and Policy in International Business. 32 (4): 785. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- National Diet Library Issue Brief, March 11, 2008: 参議院の一票の格差・定数是正問題 Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- nikkei.net, September 29, 2009: 1票の格差、大法廷30日判決 07年参院選4.86倍 Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- Asahi Shimbun, August 18, 2009: 有権者98万人増 「一票の格差」2.3倍に拡大 Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved December 17, 2002.

- Fukue, Natsuko, "The basics of being a lawmaker at the Diet", The Japan Times, January 4, 2011, p. 3.

- House of Councillors. Legislative Procedure. Published 2001. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- Asia Times Online Japan: A political tsunami approaches. By Hisane Masaki. Published July 6, 2007. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- "Diet | Japanese government". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- House of Representatives of Japan Disagreement between the Two Houses. Retrieved July 14, 2007.

- House of Representatives of Japan Sessions of the Diet. Retrieved July 14, 2007.

- House of Representatives of Japan Opening Ceremony and Speeches on Government Policy. Retrieved July 14, 2007.

- "Judgments of the Supreme Court Case 1994 (O) 1287". Supreme Court of Japan. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- "Judgments of the Supreme Court Case Number 1978 (O) 1240". Supreme Court of Japan. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- "The Constitution of Japan, CHAPTER Ⅳ THE DIET". Japanese Law Translation. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- Oda, Hiroshi (2009). "The Sources of Law". Japanese Law. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199232185.001.1. ISBN 978-0-19-923218-5.

- M. Nakamura and T. Tsunemoto, ‘The Legislative Process: Outline and Actors’, in Y.Higuchi (ed.), Five Decades of Constitutionalism in Japanese Society (Tokyo, 2001), pp. 197–219

- Fraser, Andrew; Mason, R. H. P.; Mitchell, Philip (September 16, 2005). Japan's Early Parliaments, 1890-1905: Structure, Issues and Trends. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-134-97030-8.

- Stewart Lone Provincial Life and the Imperial Military in Japan. Page 12. Published 2010. Routledge. ISBN 0-203-87235-5

- House of Representatives of Japan From Imperial Diet to National Diet. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- Henkin, Louis and Albert J. Rosenthal Constitutionalism and Rights: : the Influence of the United States Constitution Abroad. Page 424. Published 1990. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-06570-1

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication. Chapter 27 – Government Employees and Elections Archived 2012-02-29 at WebCite. Published 2003. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- Library of Congress County Data. Japan – The Legislature. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- House of Councillors: 国会の召集と会期

- House of Councillors: 参議院の緊急集会

- House of Representatives: 国会会期一覧, retrieved October 4, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diet of Japan. |

- National Diet Library: Diet and Parliaments has the Diet minutes (in Japanese) and additional information.