Syria–Lebanon campaign

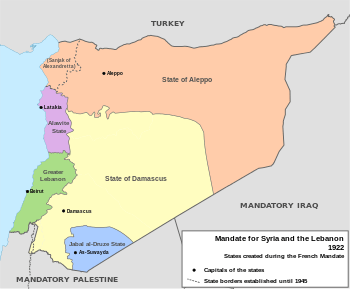

The Syria–Lebanon campaign, also known as Operation Exporter, was the British invasion of Vichy French Syria and Lebanon from June–July 1941, during the Second World War. The French had ceded autonomy to Syria in September 1936, with the right to maintain armed forces and two airfields in the territory.

On 1 April 1941, the 1941 Iraqi coup d'état had taken place and Iraq had come under the control of Iraqi nationalists led by Rashid Ali, who appealed for German support. The Anglo-Iraqi War (2–31 May 1941) led to the overthrow of the Ali regime and the installation of a British puppet government. During this conflict, key Vichy figure Admiral François Darlan had allowed German aircraft to use Vichy airfields in Syria for attacks against the British in Iraq.[3] The British invaded Syria and Lebanon in June, to prevent Nazi Germany from using the Vichy French-controlled Syrian Republic and French Lebanon as bases for attacks on Egypt, during an invasion scare in the aftermath of the German victories in the Battle of Greece (6–30 April 1941) and the Battle of Crete (20 May – 1 June). In the Western Desert Campaign (1940–1943) in North Africa, the British were preparing Operation Battleaxe to relieve the Siege of Tobruk and were fighting the East African Campaign (10 June 1940 – 27 November 1941) in Ethiopia and Eritrea.

The Vichy French made a vigorous defence of Syria; but, on 10 July, as the 21st Australian Brigade was on the verge of entering Beirut, the French sought an armistice. At one minute past midnight on 12 July, a ceasefire came into effect and ended the campaign. The Armistice of Saint Jean d'Acre (Convention of Acre) was signed on 14 July at the Sidney Smith Barracks on the outskirts of the city. Time magazine referred to the fighting as a "mixed show" while it was taking place and the campaign remains little known, even in the countries that took part. There is evidence that the British censored reportage of the fighting because politicians believed that hostilities against French forces could have a negative effect on public opinion in English-speaking countries.

Background

In May 1941, Admiral François Darlan on behalf of Vichy France signed the Paris Protocols, an agreement with the Germans. The protocols granted Germany access to military facilities in Vichy-controlled Syria.[4] The protocols remained unratified, but Charles Huntziger, the Vichy Minister of War, sent orders to Henri Dentz, the High Commissioner for the Levant, to allow aircraft of the German Luftwaffe and Italian Regia Aeronautica to refuel in Syria. Marked as Iraqi aircraft, Axis aircraft under Fliegerführer Irak landed in Syria, en route to the Kingdom of Iraq during the Anglo-Iraqi War. Part of the reason why Darlan allowed the German and Italian aircraft to use Syrian airfields was because of attacks on Vichy French ships by the British; Darlan calculated that since July 1940 167 French ships had been seized by British forces.[5] Under the Paris Protocols an agreement was also made that France would launch an offensive against the British-held Iraqi oilfields, a proposal put forward by Darlan.[6] As well as the use of Syrian airfields, the Germans also requested permission from the Vichy authorities to use Syrian railways to send armaments to Iraqi nationalists in Mosul. In return for Darlan's gestures, the Germans released 7,000 French prisoners of war, many of them being professional officers and non-commissioned officers.[7] General Archibald Percival Wavell, the Commander-in-Chief of Middle East Command, was reluctant to intervene in Syria, despite government prodding, because of the situation in the Western Desert, the imminent German attack on Crete and doubts about Free French pretensions.[8]

Prelude

Vichy Syria

Dentz was Commander in Chief of the Armée du Levant (Army of the Levant), which had regular metropolitan colonial troops and troupes spéciales (special troops, indigenous Syrian and Lebanese soldiers).[9] There were seven infantry battalions of regular French troops at his disposal, which included the 6th Foreign Infantry Regiment of the French Foreign Legion, the 24th Colonial Infantry Regiment and eleven infantry battalions of "special troops", including at least 5,000 cavalry in horsed and motorized units, two artillery groups and supporting units.[9] The Army numbered 35,000 troops, comprising 35,000 regulars including 8,000 French and 25,000 Syrian and Lebanese infantry. The French had 90 tanks (according to British estimates), the Armée de l'Air de Vichy (Vichy French Air Force) had 90 aircraft (increasing to 289 aircraft after reinforcement) and the Marine Nationale (French Navy) had two destroyers, Guépard and Valmy, plus one Sloop, the Elàn and three submarines.[10][11]

On 14 May 1941, a Royal Air Force (RAF) Bristol Blenheim bomber crew, flying a reconnaissance mission over Palmyra in central Syria, spotted a Junkers Ju 90 transport taking off, with more German and Italian aircraft seen later that day; an attack on the airfield was authorised later that evening.[12] Attacks against German and Italian aircraft staging through Syria continued and the British claimed six Axis aircraft destroyed by 8 June. Vichy French forces shot down a Blenheim on 28 May, killing the crew, and forced down another on 2 June.[13] French Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 fighters also escorted German Junkers Ju 52 aircraft into Iraq on 28 May.[14] The RAF shot down a Vichy Martin 167F bomber over the British Mandate of Palestine on 6 June.[15] While German interest in the French mandates of Syria and Lebanon was limited, Adolf Hitler permitted reinforcement of the French troops, by allowing French aircraft en route from Algeria to Syria to fly over Axis-controlled territory and refuel at the German-controlled Eleusina air base in Greece.[16] The activity of German aircraft based in Greece and the Dodecanese Islands was interpreted by the British as support for Vichy troops, but although Dentz briefly considered accepting German assistance, he rejected the offer on 13 June.[17] By the end of the Anglo-Iraqi war, all 14 of the original German Messerschmitt Bf 110 aircraft sent to Syria as well as five Heinkel He 111 and a large number of transport aircraft had been destroyed by the British.[18]

Palestine and Iraq

The British-led invasion of Syria and Lebanon aimed at preventing Nazi Germany from using the Vichy French-controlled Syrian Republic and French Lebanon for attacks on Egypt as the British fought the Western Desert Campaign (1940–1943) against Axis forces in North Africa. The concerns were that attacks by Nazi Germany from Syria and Lebanon could eventuate if the Germans had access to the airfields there and if German troops fighting at the time on the Eastern Front could link up with Vichy forces, in the event of German success against Russia, by advancing south through the Caucasus. Both of these contingencies would have exposed Allied forces in Egypt from the north at a time when all available resources needed to focus on halting the German advances from the west.[19] Although the French had ceded autonomy to Syria in September 1936, they had retained treaty rights to maintain armed forces and two airfields in the territory. From 1 April 1941, after a coup d'état, Iraq, on the eastern border of Syria, came under the control of nationalists led by Rashid Ali who were willing to appeal for German support. The Anglo-Iraqi War (2–31 May 1941) led to the installation of a pro-British government.[20]

British forces to the south of Syria in Mandate Palestine were under the command of General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson and consisted of the 7th Australian Division (minus the 18th Brigade, which was in North Africa, besieged at Siege of Tobruk), Gentforce with two Free French brigades of the 1st Free French Division (including two battalions of the 13th Foreign Legion Demi-Brigade attached to the 1st Free French Brigade) and the 5th Indian Infantry Brigade (4th Indian Infantry Division) with artillery, engineers and other support services attached to form the 5th Indian Brigade Group. In northern and central Syria, Iraq Command (Lieutenant-General Sir Edward Quinan) was used in this campaign to attack from the east, consisting of the 10th Indian Infantry Division, elements of the 17th Indian Infantry Brigade (8th Indian Infantry Division) and Habforce, the 4th Cavalry Brigade and the Arab Legion, under John Glubb (Glubb Pasha).[21] Commando and raiding operations were undertaken by No. 11 (Scottish) Commando from Cyprus,[22] as well as Palmach paramilitary and Mista'arvim squads from Mandatory Palestine.[23]

Air support was provided by squadrons from the RAF and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF); ground forces on the coast were supported by bombardments from Royal Navy (RN) and Royal Australian Navy (RAN) units of the Mediterranean Fleet. At the beginning, Air Commodore L. O. Brown, the Air officer commanding (AOC) HQ RAF Palestine and Transjordan had the understrength 11 Squadron (Blenheim Mk IV), 80 Squadron, re-equipping with Hawker Hurricanes, 3 Squadron RAAF, converting to Curtiss Tomahawks, 208 (Army Co-operation) Squadron with a flight of Hurricanes and X Flight (Gloster Gladiators). A detachment of Fleet Air Arm (FAA) 815 Naval Air Squadron (Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers) in Cyprus and 84 Squadron (Blenheims) in Iraq were to co-operate.[24]

British forces in reserve included the 6th Infantry Division (with the Czechoslovak 11th Infantry Battalion–East attached to the 23rd Infantry Brigade) and the 17th Australian Brigade.[25] In mid-June, the division with its two infantry brigades came into the line as reinforcements, mainly on the Damascus front and the southern force was placed under the command of the 1st Australian Corps on 19 June.[26][27][28] At the beginning of Operation Exporter, the British and Commonwealth force consisted of about 34,000 men (18,000 Australians, 9,000 British, 2,000 Indian and 5,000 Free French troops).[29] The RAF and RAAF had about 50 aircraft and the navy contributed the landing ship HMS Glengyle, five cruisers and eight destroyers.[30]

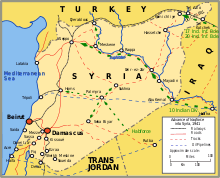

British plan of attack

The British plan of attack devised by Wilson called for four lines of invasion, on Damascus and Beirut from Palestine, on northern Syria and Palmyra (in central Syria) from Iraq and Tripoli (in northern Lebanon) also from Iraq.[31][32] The 5th Indian Brigade Group (Brigadier Wilfrid Lewis Lloyd) was ordered to cross the Syrian border from Palestine and take Quneitra and Deraa. It was anticipated that this would open the way for the 1st Free French Division to advance to Damascus. Four days after the commencement of the operation, this force was brought under unified command and was named Gentforce after its French commander, Major-General Paul Louis Le Gentilhomme.[33] The 7th Australian Division (Major-General John Lavarack (succeeded by Major-General Arthur "Tubby" Allen on 18 June when Lavarack took over Australian I Corps) advanced from Palestine along the coastal road from Haifa towards Beirut.[34] The Australian 21st Brigade was to take Beirut, advancing along the coast from Tyre, over the Litani River towards Sidon.[35] The Australian 25th Brigade was to attack the large Vichy French airbase at Rayak, advancing along a route further inland from the 21st Brigade.[36] The operation was also to include a supporting commando landing from Cyprus at the south of the Litani River.[37]

Once the two southern prongs were well engaged, it was planned that a third force, comprising formations drawn from Iraq Command, would invade Syria. The bulk of the 10th Indian Infantry Division (Major-General William "Bill" Slim) was to advance north-west up the Euphrates River from Haditha in Iraq (upstream from Baghdad), toward Deir ez Zor and thence to Raqqa and Aleppo. The manoeuvre was intended to threaten the communication and supply lines of Vichy forces defending Beirut against the Australians advancing from the south, in particular the railway line running northwards through Aleppo to Turkey (Turkey was thought by some British strategists to be sympathetic to Vichy and to Germany).[38] A group comprising two infantry battalions from the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade (10th Indian Division) and two from the 17th Indian Infantry Brigade (8th Indian Infantry Division), would operate independently, to capture all the territory in north-east Syria. The 20th Indian Infantry Brigade were to make a feint from Mosul and the 17th Indian Infantry Brigade would advance into the Bec du Canard (Duck's Bill) region, through which a railway from Aleppo ran eastward to Mosul and Baghdad.[39][40] Habforce was in Iraq attached to Iraq Command, because it had previously struck across the desert from the Transjordan border as part of the relief of RAF Habbaniya during the Anglo-Iraqi War.[41] Habforce comprised the 4th Cavalry Brigade, the 1st Battalion, Essex Regiment and the Arab Legion Mechanized Regiment, supported by field, anti-tank and anti-aircraft artillery units, to gather in western Iraq between Rutbah and the Transjordan border.[42] At the same time as the thrust up the Euphrates, Habforce would advance in a north-westerly direction to take Palmyra in Syria and secure the oil pipeline from Haditha to Tripoli.[41]

Campaign

War on land

Hostilities commenced on 8 June 1941. The battles of the campaign were:

- Battle of the Litani River (9 June): part of the advance on Beirut from Palestine

- Battle of Jezzine (13 June): part of the advance on Beirut from Palestine

- Battle of Sidon (13–15 June): part of the advance on Beirut from Palestine

- Battle of Kissoué (15–17 June): part of the advance on Damascus from Palestine

- Battle of Damascus (18–21 June): part of the advance on Damascus from Palestine

- Battle of Merdjayoun (19–24 June): part of the advance on Beirut and Damascus from Palestine

- Battle of Palmyra (1 July): part of the advance on Palmyra and Tripoli from Iraq

- Battle of Deir ez-Zor (3 July): part of the advance on central and northern Syria from Iraq

- Battle of Damour (5–9 July): part of the advance on Beirut from Palestine

- Battle of Beirut (12 July): part of the advance on Beirut from Palestine

War in the air

The initial advantage that the Vichy French Air Force (Armée de l'Air de Vichy) enjoyed did not last long. The Vichy French lost most of their aircraft destroyed on the ground where the flat terrain, the absence of infrastructure and the absence of modern anti-aircraft (AA) artillery made them vulnerable to air attacks.[43] On 26 June, a strafing run by Tomahawks of 3 Squadron RAAF, on Homs airfield, destroyed five Dewoitine D.520s of Fighter Squadron II/3 (Groupe de Chasse II/3) and damaged six more.[44]

On 10 July, five D.520s attacked Bristol Blenheim bombers of 45 Squadron RAF, which were being escorted by seven Tomahawks from 3 Squadron RAAF.[45] The French pilots claimed three Blenheims but at least four D.520s were destroyed by the Australians.[45][46] The following day, a Dewoitine pilot shot down a Tomahawk from 3 Squadron, the only one lost during the campaign.[45] By the end of the campaign, the Vichy forces had lost 179 aircraft from about 289 committed to the Levant, with remaining aircraft with the range to do so evacuating to Rhodes.[47]

War at sea

The war at sea was not a major part of Operation Exporter, although some significant actions were fought. During the Battle of the Litani River, rough seas kept commandos from landing along the coast on the first day of battle. On 9 June 1941, the French destroyers Valmy and Guépard fired on the advancing Australians at the Litani River before being driven off by shore-based artillery-fire. The French destroyers then exchanged fire with the British destroyer HMS Janus. The Royal New Zealand Navy light cruiser HMNZS Leander came to the aid of Janus along with six British destroyers and the French retired.[48] The Luftwaffe attempted to come to the aid of the French naval forces on 15 June. Junkers Ju 88s of II./LG 1 (2nd Group, Lehrgeschwader 1), attacked British warships forces off the Syrian coast and hit the destroyers HMS Ilex and Isis. That evening, French aircraft of the 4th Naval Air Group bombed British naval units off the Syrian coast.[48]

On 16 June, British torpedo aircraft sank the French destroyer Chevalier Paul, which had been en route from Toulon to Syria, carrying ammunition from Metropolitan France. The following day, British bombers attacked another French destroyer in the port of Beirut which was also carrying ammunition.[48] On the night of 22/23 June, Guépard fought a brief engagement with two British cruisers and six destroyers off of the Syrian coast, before the French destroyer retired under the cover of darkness.[49] The French suffered further losses on 25 June, when the British submarine HMS Parthian torpedoed and sank the French submarine Souffleur off the Lebanese coast; shortly afterwards, the French tanker Adour, which was carrying the entire fuel supply for the French forces in the Middle East, was attacked by British torpedo aircraft and badly damaged.[50]

Armistice

On 10 July, as the Australian 21st Brigade was on the verge of entering Beirut, Dentz sought an armistice. At one minute past midnight on 12 July, a ceasefire came into effect and ended the campaign. The Armistice of Saint Jean d'Acre (also known as the "Convention of Acre") was signed on 14 July at the Sidney Smith Barracks on the outskirts of the city of Acre.[51]

Aftermath

Analysis

Wavell had not wanted the Syrian distraction when British forces in the Mediterranean were overstretched and the unopposed entry guaranteed by the Free French appeared to be a false promise. Churchill and the CIGS forced the campaign on Wavell and when Vichy forces defended Syria, the British forces needed reinforcement, which could only be provided piecemeal. Many of the British and Commonwealth troops were novices and the hot, dry and mountainous terrain was a severe test, in which Indian Army units excelled. The Australian contingent had to cope with the worst country but conducted the most effective attack, "with a good plan carried through with great determination". The achievement of air superiority was delayed by the lack of aircraft but the urgency of the situation made it impossible for the naval and ground forces to wait. Vichy French airmen concentrated their attacks on ships and ground targets, which were highly effective until they were forced to move north. The scare caused by the German success in Crete had been exaggerated because the German parachute and glider invasion of Crete had been costly and there was little chance of the Germans gaining a bridgehead in Syria. The Germans withdrew from Syria to preserve their forces and to deprive the British of a pretext for invasion. The British invaded Syria anyway and took over naval and air bases far north of Suez and increased the safety of the oil route from Basra to Baghdad in Iraq to Haifa in Palestine.[52]

Casualties

In August, the Vichy authorities announced 6,352 casualties of whom 521 men had been killed, 1,037 were missing, 1,790 wounded and 3,004 men had been taken prisoner. After the war, Dentz stated that 1,092 men had been killed, which would mean 1,790 wounded, 466 missing and 3,004 prisoners against a British claim of 8,912 casualties of all natures.[53] The Vichy Air Force lost 179 aircraft, most destroyed on the ground, the navy lost one submarine and 5,668 men defected to the Free French.[54][55] The armistice agreement led to the repatriation to France of 37,563 military and civilian personnel in eight convoys, consisting of three hospital ships and a "gleaner" ship, from 7 August to 27 September.[56] Prisoners taken by the Vichy French forces were returned but several British prisoners of war had been sent out of Syria, some after the armistice. The delay in obtaining the return of these prisoners led to the detention of Dentz and 29 senior officers in Palestine who were released when the British prisoners were returned to Syria.[57] British and Commonwealth casualties were about 4,652; the Australians suffered 1,552 casualties, (416 men killed and 1,136 wounded.) The Free French incurred about c. 1,300 losses and 1,100 men taken prisoner; British and Indian casualties were 1,800 wounded, 1,200 men captured and 3,150 sick, including 350 malaria cases.[58] The RAF and RAAF lost 27 aircraft.[59]

Subsequent events

Operations against the Vichy regime in Syria could only be conducted with troops withdrawn from the Western Desert, a dispersal that contributed to the defeat of Operation Battleaxe and made the Syrian campaign take longer than necessary. Churchill had decided to sack Wavell in early May over his reluctance to divert forces to Iraq. Wavell was relieved on 22 June and relinquished command on 5 July, leaving for India two days afterwards.[60] In late July 1941, De Gaulle flew from Brazzaville to congratulate the victors.[61] Free French General Georges Catroux was placed in control of Syria and Lebanon and on 26 November, shortly after taking up this post, Catroux recognised the independence of Syria and Lebanon in the name of the Free French movement.[62] After elections on 8 November 1943, Lebanon became an independent state on 22 November 1943 and on 27 February 1945, declared war on Germany and the Empire of Japan.[63]

By 1945, however, continued French presence in the Levant saw nationalist demonstrations which the French attempted to quell. With heavy Syrian casualties, notably in Damascus, Churchill opposed French action but after being rebuffed by Charles De Gaulle, he ordered British forces into Syria from Jordan with orders to fire on the French. Known as the Levant Crisis – British armoured cars and troops then reached Damascus following which the French were escorted and confined to their barracks. With political pressure added, De Gaulle ordered a ceasefire and France withdrew from Syria the following year.[64]

See also

- Syria-Lebanon Campaign order of battle

- Asmahan

- Attack on Mers-el-Kébir

- 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

- Franco-Syrian Treaty of Independence (1936)

- Italian bombings on Palestine in World War II

- French Colonial Empire

- List of French possessions and colonies

Citations

- Sutherland, Jon; Canwell, Diane (2011). Vichy Air Force at War: The French Air Force that Fought the Allies in World War II. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation. pp. 53–67. ISBN 978-1-84884-336-3.

- Sutherland, Jon; Canwell, Diane (2011). Vichy Air Force at War: The French Air Force that Fought the Allies in World War II. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-84884-336-3.

- Sutherland, Jon; Canwell, Diane (2011). Vichy Air Force at War: The French Air Force that Fought the Allies in World War II. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-84884-336-3.

- Keegan p. 676

- Sutherland, Jon; Canwell, Diane (2011). Vichy Air Force at War: The French Air Force that Fought the Allies in World War II. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-84884-336-3.

- Sutherland, Jon; Canwell, Diane (2011). Vichy Air Force at War: The French Air Force that Fought the Allies in World War II. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-84884-336-3.

- Sutherland, Jon; Canwell, Diane (2011). Vichy Air Force at War: The French Air Force that Fought the Allies in World War II. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-84884-336-3.

- Raugh 1993, pp. 216–218.

- Mollo, p.144

- Playfair, 2004 pp. 200, 206

- Long, 1953, pp. 333–334, 363

- Richards, 1974, p. 338

- Sutherland, Jon; Canwell, Diane (2011). Vichy Air Force at War: The French Air Force that Fought the Allies in World War II. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-84884-336-3.

- Sutherland, Jon; Canwell, Diane (2011). Vichy Air Force at War: The French Air Force that Fought the Allies in World War II. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-84884-336-3.

- Shores, 1970, pp. 242–244

- Shores & Ehrengardt p. 30

- de Wailly p. 246

- Sutherland, Jon; Canwell, Diane (2011). Vichy Air Force at War: The French Air Force that Fought the Allies in World War II. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-84884-336-3.

- James 2017, p. 99.

- Raugh 1993, pp. 211–216.

- Playfair, 2004, p. 204, 206–209, 216

- Smith, 2010, p. 191

- Uri Ben-Eliezer, 1998, The Making of Israeli Militarism, pp.83–84.

- Playfair, 2004, pp. 205–206

- Playfair 2004, p. 209.

- Joslen 2003, p. 50.

- Playfair 2004, p. 211.

- Chappell 1987, p. 19.

- Long, 1953, p. 526

- Playfair, 2004, p. 214

- Playfair, 2004, pp. 203, 206

- James 2017, p. 119.

- Playfair, 2004, pp. 210–212

- Long (1953), pp. 338, 413

- Johnston (2005), pp. 48–55.

- Playfair, 2004, p. 208, 211, 219

- Long (1953), pp. 360–361

- Raugh 1993, pp. 221–222.

- Playfair, 2004, p. 217

- Mackenzie, p. 121

- Raugh 1993, p. 222.

- Playfair, 2004, p. 213

- Mollo, p.146

- Shores & Ehrengardt p. 94

- Herington 1954, p. 94

- Brown 1983, p. 17.

- Shores and Ehrengardt Air Pictorial August 1970, pp. 283–284.

- Piekałkiewicz, p. 144

- Piekałkiewicz, p. 146

- Piekałkiewicz, p. 147

- Playfair, 2004, pp. 221, 335–337

- Playfair, 2004, pp. 221–222

- Long, 1953, p. 526

- Mollo, p. 146

- Playfair, 2004, pp. 214, 221

- Auchinleck, p. 4216

- Auchinleck, p. 4217

- Long, 1953, p. 526

- Playfair, p. 222

- Raugh 1993, pp. 222, 238–239.

- Time magazine, Reconquering an Empire

- Playfair, 2004, p. 221

- Martin, 2011, p. 11

- Luce, Henry Robinson (1945). Time, Volume 45. Time Incorporated. pp. 25–26.

- Playfair, 2004, p. 211

- James 2017, pp. 203-205.

- Playfair, 2004, p. 220

- James 2017, pp. 225-227.

References

Books

- Auchinleck, Claud (1946). Despatch on Operations in the Middle East From 5th July, 1941 to 31st October 1941. London: War Office. in "No. 37695". The London Gazette (Supplement). 20 August 1946. pp. 4215–4230.

- Brune, Peter (2003). A Bastard of a Place: The Australians in Papua. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-011-8.

- Chappell, Mike (1987). British Battle Insignia: 1939–1940. Men-At-Arms. II. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-0-85045-739-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Wailly, H. (2016) [2006]. Invasion Syria, 1941: Churchill and De Gaulle's Forgotten War [Syrie 1941: la guerre occultée: Vichystes contre gaullistes]. trans. W. Land (2nd English trans. ed.). London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78453-449-3.

- James, Richard (2017). Australia's War with France: The Campaign in Syria and Lebanon, 1941. Newport, New South Wales: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-1-925520-92-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnston, Mark (2005). The Silent 7th: An Illustrated History of the 7th Australian Division 1940–46. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-191-7.

- Joslen, H. F. (2003) [1990]. Orders of Battle: Second World War, 1939–1945. Uckfield: Naval and Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-474-1.

- Keegan, John (2005). Dear, I. C. B.; Foot, M. R. D. (eds.). Oxford Companion to World War II. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280670-3.

- Long, Gavin (1953). "Chapters 16 to 26". Greece, Crete and Syria. Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 1, Army. II (1st online ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 3134080.

- Mackenzie, Compton (1951). Eastern Epic: September 1939 – March 1943, Defence. I. London: Chatto & Windus. OCLC 1412578.

- Martin, Chris. World War II The Book of Lists. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6163-2.

- Mollo, Andrew (1981). The Armed Forces of World War II. London: Crown. ISBN 978-0-517-54478-5.

- Playfair, Major-General I. S. O.; et al. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1956]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Germans Come to the Help of their Ally (1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. II. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-066-5.

- Owen, James (2012). Commando. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-349-12362-2.

- Piekałkiewicz, Janusz (1987). Sea War: 1939–1945. London/New York: Blandford Press. ISBN 978-0-7137-1665-8.

- Raugh, H. E. (1993). Wavell in the Middle East, 1939–1941: A Study in Generalship (1st ed.). London: Brassey's. ISBN 978-0-08-040983-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richards, Denis (1974) [1953]. Royal Air Force 1939–1945: The Fight At Odds. I (pbk. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-771592-9. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Shores, Christopher F.; Ehrengardt, Christian-Jacques (1987). L' aviation de Vichy au combat 2 La campagne de Syrie, 8 juin – 14 juillet 1941 [Vichy Air Combat: Syria Campaign, 8 June – 14 July 1941] (in French). 2. Paris: Lavauzelle. ISBN 978-2-7025-0171-9.

- Smith, C. (2010) [2009]. England's Last War Against France: Fighting Vichy 1940–1942 (Phoenix ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7538-2705-5.

- Wavell, Archibald (1946). Despatch on Operations in Iraq, East Syria and Iran from 10th April, 1941 to 12th January, 1942. London: War Office. in "No. 37685". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 August 1946. pp. 4093–4102.

Journals

- Bou-Nacklie, N. E. (1994). "The 1941 Invasion of Syria and Lebanon: The Role of the Local Paramilitary". Middle Eastern Studies. 30 (3): 512–529. doi:10.1080/00263209408701009. ISSN 1743-7881.

- Shores, Christopher F.; Ehrengardt, Christian-Jacques (July 1970). Part I. "Syrian Campaign, 1941: Forestalling the Germans: Air Battles Over S. Lebanon". Air Pictorial. 32 (7): 242–247. OCLC 29897622.

- Shores, Christopher F.; Ehrengardt, Christian-Jacques (August 1970). Part II. "Syrian Campaign, 1941: Breaking the Back of Vichy Air Strength Conclusion". Air Pictorial. 32 (8): 280–284. OCLC 29897622.

Further reading

- Gaunson, Alexander Bruce (1981). To End a Mandate: Sir E. L. Spears and the Anglo-French Collision in the Levant, 1941–1945. hydra.hull.ac.uk (PhD). University of Hull. OCLC 53527058. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.348610. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Syria-Lebanon Campaign 1941. |

- "Despatch on Operations in Iraq, East Syria, and Iran From 10th April, 1941 to 12th January 1942" (PDF). Supplement to the London Gazette, Number 37685. August 13, 1946. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- "Claude Auchinleck's Despatch on Operations in the Middle East From 5th July, 1941 to 31st October 1941". Supplement to the London Gazette, Number 37695. August 20, 1946. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- Australian War Memorial, 2005, "Syrian Campaign"

- "The Syrian Show Begins" – Time magazine article, June 18, 1941

- "Exit With A Flourish" – Time magazine article, July 28, 1941

- The Palmach

.svg.png)