Emperor Taishō

Emperor Taishō (大正天皇, Taishō-tennō, 31 August 1879 – 25 December 1926) was the 123rd Emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. He reigned as the Emperor of the Empire of Japan from 30 July 1912 until his death on 25 December 1926.

| Taishō | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg) | |||||

| Emperor of Japan | |||||

| Reign | 30 July 1912 – 25 December 1926 | ||||

| Enthronement | 10 November 1915 | ||||

| Predecessor | Meiji | ||||

| Successor | Shōwa | ||||

| Regent | Hirohito (1921–26) | ||||

| Prime Ministers | |||||

| Born | Yoshihito (嘉仁) 31 August 1879 Tōgū Palace, Akasaka, Tokyo, Japan | ||||

| Died | 25 December 1926 (aged 47) Imperial Villa, Hayama, Kanagawa, Japan | ||||

| Burial | 8 February 1927 | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| House | Imperial House of Japan | ||||

| Father | Emperor Meiji | ||||

| Mother | Yanagihara Naruko | ||||

| Religion | Shinto | ||||

| Signature | |||||

The Emperor's personal name was Yoshihito (嘉仁). According to Japanese custom, during the reign the Emperor is called "the Emperor". After death, he is known by a posthumous name, which is the name of the era coinciding with his reign. Having ruled during the Taishō period, he is known as the "Emperor Taishō".

Early life

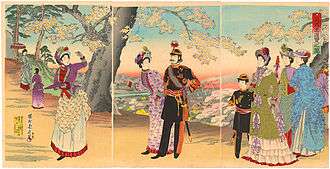

Prince Yoshihito was born at the Tōgū Palace in Akasaka, Tokyo to Emperor Meiji and Yanagihara Naruko, a concubine with the official title of gon-no-tenji ("lady of the bedchamber"). As was common practice at the time, Emperor Meiji's consort, Empress Shōken, was officially regarded as his mother. He received the personal name of Yoshihito Shinnō and the title Haru-no-miya from the Emperor on 6 September 1879. His two older siblings had died in infancy, and he too was born sickly.[1]

Prince Yoshihito contracted cerebral meningitis within three weeks of his birth.[2] (It has also been rumoured that he suffered from lead poisoning, supposedly contracted from the lead-based makeup his wet nurse used.)

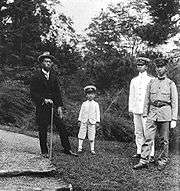

As was the practice at the time, Prince Yoshihito was entrusted to the care of his great-grandfather, Marquess Nakayama Tadayasu, in whose house he lived from infancy until the age of seven. Prince Nakayama had also raised his grandson, Emperor Meiji, as a child.[3]

From March 1885, Prince Yoshihito moved to the Aoyama Detached Palace, where he was tutored in the mornings on reading, writing, arithmetic, and morals, and in the afternoons on sports, but progress was slow due to his poor health and frequent fevers.[4] From 1886, he was taught together with 15–20 selected classmates from the ōke and higher ranking kazoku peerage at a special school, the Gogakumonsho, within the Aoyama Palace.[4]

Yoshihito was officially declared heir on 31 August 1887, and had his formal investiture as crown prince on 3 November 1888. While crown prince, he was often referred to simply as Tōgu (東宮) (a long-used generic East Asian term meaning crown prince).

Education and training

In September 1887, Yoshihito entered the elementary department of the Gakushūin; but, due to his health problems, he was often unable to continue his studies. For health reasons, he spent much of his youth at the Imperial villas at Hayama and Numazu, both of which are located at the sea. Although the prince showed skill in some areas, such as horse riding, he proved to be poor in areas requiring higher-level thought. He was finally withdrawn from Gakushuin before finishing the middle school course in 1894. However, he did appear to have an aptitude for languages and continued to receive extensive tutoring in French, Chinese, and history from private tutors at the Akasaka Palace; Emperor Meiji gave Prince Takehito responsibility for taking care of Prince Yoshihito, and the two princes became friends.

From 1898, largely at the insistence of Itō Hirobumi, the Prince began to attend sessions of the House of Peers of the Diet of Japan as a way of learning about the political and military concerns of the country. In the same year, he gave his first official receptions to foreign diplomats, with whom he was able to shake hands and converse graciously.[5] His infatuation with western culture and tendency to sprinkle French words into his conversations was a source of irritation for Emperor Meiji.[6]

In October 1898, the Prince also traveled from the Numazu Imperial Villa to Kobe, Hiroshima, and Etajima, visiting sites connected with the Imperial Japanese Navy. He made another tour in 1899 to Kyūshū, visiting government offices, schools and factories (such as Yawata Iron and Steel in Fukuoka and the Mitsubishi shipyards in Nagasaki).[7]

Marriage

On 10 May 1900, Crown Prince Yoshihito married the then 15-year-old Kujō Sadako (the future Empress Teimei), daughter of Prince Kujō Michitaka, the head of the five senior branches of the Fujiwara clan. She had been carefully selected by Emperor Meiji for her intelligence, articulation, and pleasant disposition and dignity – to complement Prince Yoshihito in the areas where he was lacking.[2] The Akasaka Palace was constructed from 1899 to 1909 in a lavish European rococo style, to serve as the Crown Prince's official residence. The Prince and Princess had the following children:

| Name | Birth | Death | Marriage | Issue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hirohito, Emperor Shōwa (裕仁, 昭和天皇) | 29 April 1901 | 7 January 1989 | 26 January 1924 | Princess Nagako Kuni | |

| Yasuhito, Prince Chichibu (秩父宮雍仁親王) | 25 June 1902 | 4 January 1953 | 28 September 1928 | Setsuko Matsudaira | none |

| Nobuhito, Prince Takamatsu (高松宮宣仁親王) | 3 January 1905 | 3 February 1987 | 4 February 1930 | Kikuko Tokugawa | none |

| Takahito, Prince Mikasa (三笠宮崇仁親王) | 2 December 1915 | 27 October 2016 | 22 October 1941 | Yuriko Takagi | |

In 1902, Yoshihito continued his tours to observe the customs and geography of Japan, this time of central Honshū, where he visited the noted Buddhist temple of Zenkō-ji in Nagano.[8] With tensions rising between Japan and Russia, Yoshihito was promoted in 1903 to the rank of colonel in the Imperial Japanese Army and captain in the Imperial Japanese Navy. His military duties were only ceremonial, but he traveled to inspect military facilities in Wakayama, Ehime, Kagawa and Okayama that year.[9]

In October 1907, the Crown Prince toured Korea, accompanied by Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, General Katsura Tarō, and Prince Arisugawa Taruhito. It was the first time an heir apparent to the throne had ever left Japan.[10] During this period, he began studying the Korean language, although he never became proficient at it.

As Emperor

On 30 July 1912, upon the death of his father, Emperor Meiji, Prince Yoshihito mounted the throne. The new Emperor was kept out of view of the public as much as possible; having suffered from various neurological problems. At the rare occasions he was seen in public, the 1913 opening of the Imperial Diet of Japan, he is famously reported to have rolled his prepared speech into a cylinder and stared at the assembly through it, as if through a spyglass.[11] Although rumors attributed this to poor mental condition, others, including those who knew him well, believed that he may have been checking to make sure the speech was rolled up properly, as his manual dexterity was also handicapped.[12]

His articulation and charisma (in contrast to Emperor Meiji), his disabilities and his eccentricities, led to an increase in incidents of lèse majesté. As his condition deteriorated, he had less and less interest in daily political affairs, and the ability of the genrō, Keeper of the Privy Seal, and Imperial Household Minister to manipulate his decisions came to be a matter of common knowledge.[13] The two-party political system that had been developing in Japan since the turn of the century came of age after World War I, giving rise to the nickname for the period, "Taishō Democracy", prompting a shift in political power to the Imperial Diet of Japan and the democratic parties.[14]

After 1918, the Emperor no longer was able to attend Army or Navy maneuvers, appear at the graduation ceremonies of the military academies, perform the annual Shinto ritual ceremonies, or even attend the official opening of sessions of the Diet of Japan.[15]

After 1919, he undertook no official duties, and Crown Prince Hirohito was named prince regent (sesshō) on 25 November 1921.[16]

Taishō's reclusive life was unaffected by the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923. Fortuitously, he had moved by royal train to his summer palace at Nikko the week before the disaster; but his son, Crown Prince Hirohito, remained at the Imperial Palace where he was at the heart of the event.[17] Carrier pigeons kept the Emperor informed as information about the extent of the devastation became known.[18]

Death

In early December 1926, it was announced that the Emperor had pneumonia. Taishō died of a heart attack at 1:25 a.m. in the early morning of 25 December 1926, at the Hayama Imperial Villa at Hayama, on Sagami Bay south of Tokyo (in Kanagawa Prefecture).[19]

The funeral was held at night (February 7 to February 8, 1927) and consisted of a 4-mile-long procession in which 20,000 mourners followed a herd of sacred bulls and an ox-drawn cart containing the imperial coffin. The funeral route was lit with wood fires in iron lanterns. The Emperor's coffin was then transported to his mausoleum in the western suburbs of Tokyo.[20]

Taishō has been called the first Tokyo Emperor because he was the first to live his entire life in or near Tokyo. Taishō's father was born and reared in Kyoto; and although he later lived and died in Tokyo, Meiji's mausoleum is located on the outskirts of Kyoto, near the tombs of his Imperial forebears; but Taishō's grave is in Tokyo, in the Musashi Imperial Graveyard in Hachiōji.[21] His son, the Emperor Shōwa, is buried next to him.

Titles and styles

- 31 August 1879 – 6 September 1879: His Imperial Highness Prince Yoshihito

- 6 September 1879 – 3 November 1888: His Imperial Highness The Prince Haru

- 3 November 1888 – 30 July 1912: His Imperial Highness The Crown Prince

- 30 July 1912 – 25 December 1926: His Majesty The Emperor

- Posthumous title: His Majesty Emperor Taishō

Honours

National honours

- Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum

- Recipient of the Order of the Precious Crown

- Recipient of the Order of the Rising Sun

- Order of the Golden Kite, 3rd class

Foreign honours

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Order of George I

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer

_crowned.svg.png)

- Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, 1900

- Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, 1900

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy, 1900

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Marriage | Issue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hirohito, Emperor Shōwa | 29 April 1901 | 7 January 1989 | 26 January 1924 | Princess Nagako of Kuni | Shigeko, Princess Teru Sachiko, Princess Hisa Kazuko, Princess Taka Atsuko, Princess Yori Akihito, Emperor of Japan Masahito, Prince Hitachi Takako, Princess Suga |

| Yasuhito, Prince Chichibu | 25 June 1902 | 4 January 1953 | 28 September 1928 | Setsuko Matsudaira | |

| Nobuhito, Prince Takamatsu | 3 January 1905 | 3 February 1987 | 4 February 1930 | Kikuko Tokugawa | |

| Takahito, Prince Mikasa | 2 December 1915 | 27 October 2016 | 22 October 1941 | Yuriko Takagi | Princess Yasuko of Mikasa Prince Tomohito of Mikasa Yoshihito, Prince Katsura Princess Masako of Mikasa Norihito, Prince Takamado |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Emperor Taishō[31] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Taishō period

References

Citations

- Keene, Emperor of Japan:Meiji and His World. page 320-321.

- Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Page 22

- Donald Calman, Nature and Origins of Japanese Imperialism (2013), pp. 92–93

- Keene, Emperor of Japan:Meiji and His World. page 397-398.

- Keene, Emperor of Japan:Meiji and His World. page 547.

- Keene, Emperor of Japan:Meiji and His World. page 552.

- Keene, Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World. page 554.

- Keene, Emperor of Japan:Meiji and His World. page 581.

- Keene, Emperor of Japan:Meiji and His World. page 599.

- Keene, Emperor of Japan:Meiji and His World. page 652.

- See Asahi Shimbun, March 14, 2011, among many other reports.

- Nagataka Kuroda. "Higeki no Teiou - Taisho Tennou". Bungeishunjū, February 1959

- Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Page 129

- Hoffman, Michael (July 29, 2012), "The Taisho Era: When modernity ruled Japan's masses", Japan Times, p. 7

- Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Page 53

- Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Page 123

- Hammer, Joshua. (2006). Yokohama Burning, p. 44.

- Hammer, p. 194; citing "Carrier Pigeons Take News of Disaster:Wing Their Way from the Flaming City," Japan Times & Mail (Earthquake Edition). 6 September 1923, p. 1.

- Seidensticker, Edward. (1990). Tokyo Rising, p. 18.

- Ronald E. Yates, World Leaders Bid Hirohito Farewell, Chicago T, February 24, 1989 (online), accessed 13 Oct 2015

- Seidensticker, p. 20.

- "A Szent István Rend tagjai" Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Royal Decree of 14 November 1916

- Jørgen Pedersen (2009). Riddere af Elefantordenen, 1559–2009 (in Danish). Syddansk Universitetsforlag. p. 466. ISBN 978-87-7674-434-2.

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreichs Bayern (1906), "Königliche-Orden" p. 8

- Sergey Semenovich Levin (2003). "Lists of Knights and Ladies". Order of the Holy Apostle Andrew the First-called (1699-1917). Order of the Holy Great Martyr Catherine (1714-1917). Moscow.

- Royal Thai Government Gazette (9 December 1900). "ข้อความในใบบอกพระยาฤทธิรงค์รณเฉท อรรคราชทูตสยามกรุงญี่ปุ่น เรื่อง พระราชทานเครื่องราชอิศริยาภรณ์ มหาจักรีบรมราชวงษ์แก่มกุฎราชกุมาร กรุงญี่ปุ่น" (PDF) (in Thai). Retrieved 2019-05-08. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Caballeros de la insigne orden del toisón de oro". Guía Oficial de España (in Spanish). 1911. p. 160. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- Sveriges Statskalender (in Swedish), 1909, p. 613, retrieved 2018-01-06 – via runeberg.org

- "List of the Knights of the Garter=François Velde, Heraldica.org". Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- "Genealogy". Reichsarchiv (in Japanese). Retrieved 24 October 2017.

Sources

- Hammer, Joshua. (2006). Yokohama Burning: the Deadly 1923 Earthquake and Fire that Helped Forge the Path to World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-6465-5 (cloth)

- Seidensticker, Edward. (1990). Tokyo Rising. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-54360-4 (cloth) [reprinted by Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1991: ISBN 978-0-674-89461-7 (paper)]

- Bix, Herbert P.. Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Harper Perennial (2001). ISBN 0-06-093130-2

- Fujitani, T. Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan. University of California Press; Reprint edition (1998). ISBN 0-520-21371-8

- Keene, Donald. Emperor Of Japan: Meiji And His World, 1852–1912. Columbia University Press (2005). ISBN 0-231-12341-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taishō Emperor. |

Emperor Taishō Born: 31 August 1879 Died: 25 December 1926 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Emperor Meiji (Mutsuhito) |

Emperor of Japan 30 July 1912 – 25 December 1926 |

Succeeded by Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito) |