Battle of Munda Point

The Battle of Munda Point was a battle, from 22 July – 5 August 1943, between primarily United States Army and Imperial Japanese Army forces during the New Georgia Campaign in the Solomon Islands in the Pacific War. The battle took place following a landing by U.S. troops on the western coast of New Georgia from Rendova, as part of an effort to capture the Japanese airfield that had been constructed at Munda Point. This advance had become bogged down and while the Allies brought forward reinforcements and supplies, the Japanese had launched a counterattack on 17–18 July. This effort was ultimately unsuccessful and afterwards U.S. forces launched a corps-level assault to reinvigorate their effort to capture the airfield. Against this drive, Japanese defenders from three infantry regiments offered stubborn resistance, but were ultimately forced to withdraw, allowing U.S. forces to capture the airfield on 5 August. The airfield later played an important role in supporting the Allied campaign on Bougainville in late 1943.

Background

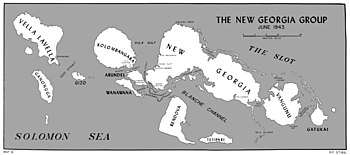

Munda Point is on the western coast of mainland New Georgia. To its northwest lies Bangaa Island and to its south is Rendova, from which it is separated by the Blanche Channel and the Munda Bar.[2][3] At the time of the battle, the location's significance was derived from the airfield that the Japanese had established there. In the wake of the Guadalcanal campaign, concluded in early 1943, the Allies formulated plans to advance through the Central Solomons towards Bougainville, in conjunction with further operations in New Guinea, as part of the effort to reduce the main Japanese base around Rabaul under the guise of Operation Cartwheel. Capture of the airfield at Munda would facilitate further assaults on Vila, on Kolombangara, and Bougainville.[4][5] For the Japanese, New Georgia formed a key part in their defenses along the southern approaches to Rabaul and they sought to defend the area strongly, moving reinforcements by barge along the Shortlands–Vila–Munda supply line.[6][7]

Rendova was secured in short order by U.S. forces who landed there on 30 June as part of the preliminary phase of the Allied operation to secure New Georgia. On 2 July 1943, Major General John H. Hester's 43rd Infantry Division crossed the Blanche Channel from Rendova. A few days later they began a westward advance towards the Japanese-held airfield at Munda Point. Over the course of two weeks, these forces undertook a slow advance along the coast towards the airfield. Held up by the dense jungle, difficult terrain and strong Japanese defenses, the U.S. troops became disorganized and the advance stalled after reaching the Japanese main line of resistance on 15 July.[8]

The inexperienced U.S. troops, hungry and tired, began to lose their fire discipline and forward momentum.[9] There were also a high number of severe cases of combat stress reaction among U.S. troops during this time.[10][11] Historian Samuel Eliot Morison described the situation:

Darkness came to the jungle like the click of a camera shutter. Then the Japanese crept close to the American lines. They attacked with bloodcurdling screams, plastered bivouacs with artillery and mortar barrages, crawled silently into American foxholes and stabbed or strangled the occupants. Often they cursed loudly in English, rattled their equipment, named the American commanding officers and dared the Americans to fight, reminding them that they were "not in the Louisiana maneuvers now." For sick and hungry soldiers who had fought all day, this unholy shivaree was terrifying. They shot at everything in sight – fox fire on rotting stumps, land crabs clattering over rocks, even comrades.[12]

In order to renew the offensive, Major General Oscar W. Griswold, commander XIV Corps, was sent to New Georgia to assess the situation. He reported back to Admiral William Halsey on Noumea that the situation was dire and requested reinforcements in the form of at least another division to break the stalemate.[13] Griswold took over command of the troops in the field on 15 July and began preparations for a corps-level offensive. The movement of reinforcements and supplies from Guadalcanal and the Russell Islands took time, and Sasaki took advantage of the disorder on the American side,[14] launching a counterattack on 17/18 July.[15]

Japanese preparations for the counterattack had begun with the movement of reinforcements from the 13th Infantry Regiment from Kolombangara and Bairoko.[16] On 14 July, six companies began their approach march, but were held up for three days by difficult terrain before reaching their assembly area. On 17 July, the Japanese troops launched an attack against the U.S. rear areas, raiding the 43rd Infantry Division's command post, kitchen areas and medical aid stations. Elements of the attacking force managed to penetrate as far as the original U.S. beachhead around Zanana, but were repulsed by artillery and counter penetration forces. Meanwhile, the Japanese 229th Infantry Regiment attacked the high ground held by the U.S. 103rd and 169th Infantry Regiments, where they came up against stiff defense. Eventually, the Japanese counterattack petered out on 18 July.[17]

Battle

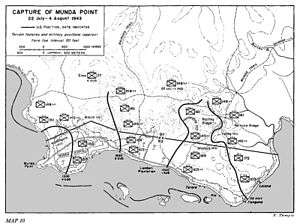

The U.S. commander, Griswold, issued orders for an offensive aimed at capturing Munda airfield on 22 July.[18] On 23 July, the U.S. 43rd Infantry Division was reinforced by the 37th and 25th Infantry Divisions. These divisions were commanded by Major Generals Robert S. Beightler and J. Lawton Collins.[19][20] The following day, the U.S. preparations for the offensive were completed. The 37th was deployed inland with three regiments, the 145th,161st and 148th, positioned along the front from south to north. On their left, along the coast, the 43rd Infantry Division pushed two regiments forward, the 103rd and 172nd, and held the 169th back in reserve.[17][21] In total, U.S. forces assigned to the effort to capture Munda numbered around 30,000 men. Seven infantry regiments were ultimately committed from three different divisions.[1][22]

Meanwhile, the Japanese commander, Major General Minoru Sasaki, disposed three battalions of Colonel Genjiro Hirata's 229th Infantry Regiment, reinforced by a single company from Colonel Wakichi Hisashige's 230th Infantry Regiment, which occupied a position around Kokengola Hill. The 13th Infantry Regiment was initially withdrawn northeast of Munda, but would be committed against the U.S. right flank, with initial Japanese plans conceiving a renewed counterattack on 25 July from this flank, although this did not come to fruition as the Allies launched their effort before the Japanese could execute their own.[23] Japanese indirect fire support consisted of a number of units, including antiaircraft and antitank units.[17][21] The Japanese committed around 8,000 troops.[1][22] These troops formed Sasaki's Southeastern Detachment and were drawn from the 6th and 38th Infantry Divisions, the 10th Mountain Artillery Regiment and the 15th Field Antiaircraft Regiment.[24][25]

Across a frontage of around 3,200 yards (2,900 m) the Japanese defenders had established a series of defenses along a northwesterly axis from the beach at Ilangana. These defenses consisted of strong pillboxes and fortifications amidst thick jungle. These dominated several high features including Shimizu Hil, Horsehoe Hill, Kelley Hill and Reincke Ridge.[26] Situated to provide mutual support, the pillboxes were well constructed with coral and coconut logs. Dug-in several feet beneath the ground, they were well camouflaged and only a small part showed above ground with firing points for machine gunners and riflemen.[27]

The U.S. attack began on 25 July, with the 37th Division attacking towards Bibilo Hill while the 43rd Division drove towards Lambeti Plantation and the airfield.[28] The attack was heavily supported by naval gunfire and artillery support. This included 105 mm and 155 mm field pieces, while the destroyers fired their 6-inch deck guns. Allied aircraft also carried out airstrikes along the coast. While visually spectacular, and involving thousands of rounds, the preparatory fires did not initially result in a breakthrough for U.S. forces. The defending Japanese troops were able to reoccupy their pillboxes after the barrage. The U.S. Marine M3 Stuart tanks from the 9th Defense Battalion that were supporting the infantry found the ground too steep and eventually the U.S. attack stalled. No gains were made by the 37th Infantry Division while the 43rd Infantry Division gained only a small amount of ground. The Japanese had constructed many pillboxes along the front and on 26 July, the U.S. 103rd Infantry Regiment came up against 74 of these structures in a narrow front. Again, the U.S. troops utilized indirect fire to reduce these obstacles, while infantry attacked armed with flamethrowers, and operating closely alongside Marine tanks. In many cases, the Japanese reoccupied these pillboxes in the darkness; as a result, later the U.S. troops took to ripping the roofs off these structures.[29][30]

Inland, the U.S. troops advanced towards towards Bilbao Hill. In the center of the frontline, the US infantrymen were supported by six tanks from the 10th Defense Battalion that had recently arrived from the Russell Islands,[31] and attacked with flamethrowers, small arms and grenades. Two Marine tanks were destroyed in this fighting, while the others were forced to withdraw, and over the course of the next couple of days heavy fighting occurred. Even when pillboxes were overrun, invariably one defender remained to fight to the death.[32]

On the extreme right flank, though, the advancing U.S. troops made steady gains over several days. Here, the advance pushed too far forward, outstripping their supply line and neighboring units, and on 28 July the Japanese 13th Infantry Regiment found a gap in the U.S. line between the 148th and 161st Infantry Regiments, and surrounded a U.S. supply dump. In response, two battalions of the U.S. divisional reserve (169th Infantry Regiment) were committed. Four U.S. rifle companies counterattacked the 200 Japanese troops around the supply dump, restoring the situation while incurring heavy casualties. Meanwhile, the offensive in the south continued towards Shimzu Hill, about 1,000 yards (910 m) from the outer limits of the airfield continued.[33][34]

A change of command of the 43rd Infantry Division took place on 29 July, with Major General John R. Hodge taking over from Hester.[35] On 30 July, the Japanese commander, Sasaki, ordered a withdrawal closer to the airfield. Shimzu Hill was taken by U.S. forces the following day.[33][34] As the fighting continued, the Japanese medical and resupply systems broke down as the Sasaki's men were reduced to around half strength. On 1 August, elements from the 103rd Infantry Regiment reached the outskirts of the airfield, while the 27th Infantry Regiment, detached from the 25th Infantry Division, was pushed into the line to reinvigorate the final drive. Japanese troops defending the ridges along the Munda Trail hastily withdrew when pressed and by 2 August only limited opposition was provided, except around Bibilo and Kokoengolo Hills.[36]

For the Japanese, the situation grew desperate. Communications with Rabaul had been severed and casualties had heavily reduced their fighting elements with many of the senior leaders among the dead or wounded. The advancing U.S. divisions converged around the eastern edges of the airfield on 3 August, and although Sasaki ordered an evacuation that day, Japanese defenders continued to offer resistance around the hills. Throughout 4 August, Japanese pillboxes and foxholes were reduced by U.S. troops attacking with indirect fire support weapons and machine guns.[1][37][36] After encircling the airfield, US forces captured Bibilo Hill on 4 August.[38] Fighting alongside Marine tanks and supported by mortars and 37 mm guns, U.S. infantrymen captured the airfield late on 5 August.[1][37][36]

Aftermath

After losing the battle for the airfield, Japanese forces began evacuating New Georgia and a large number of troops redeployed to defend nearby Kolombangara,[39] while others were sent to Bangaa Islet, which was about 4,000 yards (3,700 m) west of Munda. Initially, Sasaki believed further troops would be sent south from Rabaul to support a counterattack in New Georgia;[40] but by the end of the month the Japanese reverted to delaying tactics to enable a withdrawal from the Central Solomons.[41] The Allies employed the airfield to cover landings on Vella Lavella, and in its campaign as part of Operation Cartwheel to isolate the major Japanese base at Rabaul, New Britain.[42] Casualties during the fighting around Munda amounted to 4,994 U.S. troops killed or wounded from 2 July until the capture of the airfield. Against this, the Japanese lost 4,683 killed, with an unknown wounded over the same period.[1]

Meanwhile, several Naval Construction Battalions, including the 24th and 73rd, began repairing the airfield and expanding its capacity. By mid-August, two U.S. Marine fighter squadrons were operating from the airfield in support of operations on Vella Lavella. Throughout this period, U.S. ground forces on New Georgia undertook mopping up operations, advancing beyond Munda. This saw the 27th and 161st Infantry Regiments advance north towards Bairoko. The 27th cleared both Mount Tirokiambo and Mount Bao,[43] while the 161st closed in on Bairoko, which was secured by 24/25 August. Meanwhile, the 169th and 172nd Infantry Regiments secured Bangaa Islet by 21 August and Arundel Island was captured by U.S. forces in early September.[44]

During the Bougainville campaign, commencing in late 1943, over 100 Allied aircraft operated from Munda airfield. It was, according to author Mark Stille, the "most important airfield" used to support the Allied invasion.[45] Three U.S. Army soldiers received the Medal of Honor for their actions during the fighting around Munda Point: First Lieutenant Robert S. Scott (172nd Infantry Regiment), Private First Class Frank J. Petrarca (145th Infantry Regiment, medic), and Private Rodger W. Young (148th Infantry Regiment).[46]

Notes

- Rentz, Marines in the Central Solomons, p. 93

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 69 (map)

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 201 (map)

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 73

- Rentz, Marines in the Central Solomons, p. 52

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, backcover

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 180

- Hammel, The Munda Trail, p. 109

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville, pp. 52–54

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 120

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 177

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 199

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 198

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 199

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 135–136

- Shaw & Kane, Isolation of Rabaul, pp. 99, 104–105

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville, p. 55

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 143–144

- Miller Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 137 & 144

- Hammel, Munda Trail, p. 128

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 145 (map)

- Rottman, Japanese Army in World War II, p. 67

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 202

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville, p. 32

- Hammel, Munda Trail, p. 240

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 144–145

- Lofgren, Northern Solomons, p. 20

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 144

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville, p. 61

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 203–204

- Hammel, The Munda Trail, pp. 108 & 123

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 204

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville, pp. 60–61

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 204–205

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 149

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 205–206

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville, pp. 61–62

- Lofgren, Northern Solomons, p. 23

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 171–172

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville, p. 62

- Rentz, Marines in the Central Solomons, p. 127

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 165–167

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville, pp. 56–57 (map)

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 167–172, 184

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville, p. 61

- Lofgren, Northern Solomons, pp. 22–23

References

- Hammel, Eric M. (1999). Munda Trail: The New Georgia Campaign, June-August 1943. Pacifica Press. ISBN 0-935553-38-X.

- Lofgren, Stephen J. (2000). Northern Solomons. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 835434865. CMH Pub 72-10. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Miller, John, Jr. (1959). "Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul". United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army. OCLC 494892065. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, vol. 6 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Castle Books. OCLC 248349913.

- Rentz, John (1952). "Marines in the Central Solomons". Historical Branch, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Duncan Anderson (ed.). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43. Oxford and New York: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-870-7.

- Stille, Mark (2018). The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-47282-447-9.

Further reading

- Altobello, Brian (2000). Into the Shadows Furious. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-717-6.

- Craven, Wesley Frank; James Lea Cate. "Vol. IV, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, August 1942 to July 1944". The Army Air Forces in World War II. U.S. Office of Air Force History. Archived from the original on 26 November 2006. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- Day, Ronnie (2016). New Georgia: The Second Battle for the Solomons. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253018773.

- Feldt, Eric Augustus (1991) [1946]. The Coastwatchers. Victoria, Australia: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014926-0.

- Hayashi, Saburo (1959). Kogun: The Japanese Army in the Pacific War. Marine Corps. Association. ASIN B000ID3YRK.

- Hoffman, Jon T. (1995). "New Georgia" (brochure). From Makin to Bougainville: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War. Marine Corps Historical Center. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- Horton, D. C. (1970). Fire Over the Islands. ISBN 0-589-07089-4.

- Lord, Walter (2006) [1977]. Lonely Vigil; Coastwatchers of the Solomons. New York: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-466-3.

- Melson, Charles D. (1993). "Up the Slot: Marines in the Central Solomons". World War II Commemorative Series. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. p. 36. Retrieved 26 September 2006.

- Mersky, Peter B. (1993). "Time of the Aces: Marine Pilots in the Solomons, 1942–1944". Marines in World War II Commemorative Series. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- McGee, William L. (2002). The Solomons Campaigns, 1942–1943: From Guadalcanal to Bougainville--Pacific War Turning Point, Volume 2 (Amphibious Operations in the South Pacific in WWII). BMC Publications. ISBN 0-9701678-7-3.

- Radike, Floyd W. (2003). Across the Dark Islands: The War in the Pacific. ISBN 0-89141-774-5.

- Rhoades, F. A. (1982). A Diary of a Coastwatcher in the Solomons. Fredericksburg, Texas: Admiral Nimitz Foundation.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Douglas T. Kane (1963). "Volume II: Isolation of Rabaul". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Archived from the original on 20 November 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- United States Army Center of Military History. "Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, Volume II – Part I". Reports of General MacArthur. Retrieved 8 December 2006. – Translation of the official record by the Japanese Demobilization Bureaux detailing the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy's participation in the Southwest Pacific area of the Pacific War.