Drive on Munda Point

The Drive on Munda Point was an offensive by mainly United States Army forces against Imperial Japanese forces on New Georgia in the Solomon Islands from 2–17 July 1943. The Japanese forces, mainly from the Imperial Japanese Army, were guarding an airfield at Munda Point on the western coast of the island that the U.S. wished to capture as one of the key objectives of the New Georgia campaign. After landing around Zanana on 2 July from Rendova, U.S. troops began a westward advance towards the airfield at Munda. Held up by difficult terrain and stubborn Japanese defense, elements of three U.S. regiments advanced slowly along the Munda trail over the course of two weeks. The slow progress resulted in a reorganization of the U.S. forces assigned to the drive, and preparations were made for a corps-level offensive, but before this could be launched, the Japanese launched a counterattack on 17 July.

Background

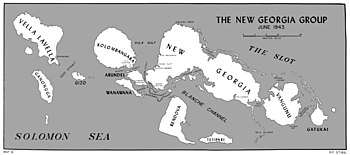

Munda Point lies on the western coast of mainland New Georgia. To its northwest lies Bangaa Island and to its south lies Rendova, from which it is separated by the Blanche Channel and the Munda Bar.[1][2] At the time of the battle, the location's significance was derived from the airfield that the Japanese had established there. In the wake of the Guadalcanal campaign, concluded in early 1943, the Allies formulated plans to advance through the Central Solomons towards Bougainville, in conjunction with further operations in New Guinea, as part of the effort to reduce the main Japanese base around Rabaul under the guise of Operation Cartwheel. Capture of the airfield at Munda would facilitate further assaults on Vila, on Kolombangara, and Bougainville.[3][4] For the Japanese, New Georgia formed a key part in their defenses along the southern approaches to Rabaul and they sought to defend the area strongly, moving reinforcements by barge along the Shortlands–Vila–Munda supply line.[5][6]

The campaign plan for securing New Georgia, designated Operation Toenails by U.S. planners, involved several landings by elements of Major General Oscar Griswold's XIV Corps to secure staging areas and an airfield in the southern part of New Georgia at Wickham Anchorage, Viru Harbor and Rendova. These would then be garrisoned to support the movement of troops and supplies from Guadalcanal to Rendova, which would be built up as base for further operations in New Georgia focused on securing the airfield at Munda.[3][4]

Efforts by U.S. forces to secure a lodgment on the west coast of New Georgia began early on 30 June when two companies from the 169th Infantry Regiment were landed offshore from Zanana, to secure several islands that sat at the mouth of the Onaiavisi Entrance to Roviana Lagoon. After linking up with a small party of local guides and a reconnaissance force that had been sent ahead, these troops consolidated their position and then moved to the mainland to begin scouting the area around Zanana towards the Barike River, and also between the Japanese airfield at Munda Point and Bairoko Harbor. To support this effort, a company of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion had been scheduled to reinforce the 169th Infantry Regiment, but they were unable to be released from operations to secure Segi Point and Viru Harbor and in their stead a company of Fijian and Tongan troops from a New Zealand-trained commando unit was detailed to assist.[7][8]

Battle

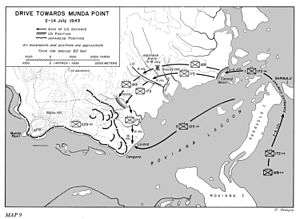

On 2 July, after the landings on Rendova, a company from the 169th Infantry Regiment and the entire 1st Battalion, 172nd Infantry Regiment, began to move to the New Georgia mainland as part of efforts to secure Munda Point. Detached from Major General John H. Hester's 43rd Infantry Division, these troops formed part of the force designated as the Southern Landing Group under the command of the assistant division commander, Brigadier General Leonard F. Wing. After night time reconnaissance patrols proved unsuccessful, on the afternoon of 2 July, a daylight crossing was undertaken utilizing a force of twelve Landing Craft Infantry vessels and four Landing Craft Tank vessels. Guided by local scouts in canoes, and covered by three artillery battalions, the U.S. troops crossed the 8-mile (13 km) Blanche Channel before passing through Onaiavisi Entrance and into Roviana Lagoon and landing around Zanana, 5 miles (8.0 km) east of Munda. After establishing a perimeter at Zanana, and building up further artillery support—four U.S. Army artillery battalions and two Marine batteries—the remaining elements of both regiments began arriving around the beachhead in preparation for the advance westward. This concentration was completed by 6 July. Meanwhile, reconnaissance troops, including elements from the New Zealand-led 1st Company, South Pacific Scouts and coastwatchers began preliminary operations.[9]

Prior to the start of the New Georgia campaign, Allied intelligence had assessed that there were between 2,000 and 3,000 Japanese personnel in the Munda area. In reality there were 4,500 men defending Munda, of which 2,000 were Imperial Japanese Army personnel while the remainder were drawn from the Imperial Japanese Navy.[10] Commanded by Colonel Genjiro Hirata, the Japanese forces defending Munda consisted of several battalions from the 229th Infantry Regiment as well as artillery, engineer, signals and medical support elements.[11] These troops had been detached from Major General Minoru Sasaki's Southeast Detachment and from 13 July, the 229th was reinforced with 1,300 troops from the 13th Infantry Regiment, which moved from Bairoko via barge, where they had been relieved by the 2nd Battalion, 45th Infantry Regiment.[12][13]

On 4 July, the U.S. troops undertook a preliminary move prior to beginning their advance, marching towards a line of departure along the Barike River about 3 miles (4.8 km) away.[14] Meanwhile, on the northern coast of New Britain, a force of U.S. Marines and Army troops landed at Rice Anchorage in an effort to block the movement of Japanese reinforcements down the Munda trail.[15] The 172nd reached the river on 6 July, but the 169th, which had adopted the inland route, was held up by a company from the Japanese 229th Infantry Regiment, and did not reach the river until 8 July. The U.S. troops, under orders from Hester, began a general attack the following day, supported by 155 mm guns firing from Rendova.[16] The terrain between the landing beach at Zanana and the objective at Munda Point was not conducive to a quick approach, and U.S. planners had failed to appreciate the difficulty the troops would have traversing the single, narrow track or through the dense jungle, which was crossed by fast flowing creeks and streams, and flanked by rocky ridges and deep ravines. The advancing U.S. troops found navigation difficult and were forced into a narrow front as the Japanese resistance mounted.[16][17]

In an effort to breakthrough, on 9 July, Hester ordered the 172nd Infantry Regiment to carry out a flanking move to the north to attack the Japanese position in the rear, while the 169th Infantry Regiment continued its frontal assault; although the attack was supported by heavy artillery, naval gunfire support and air strikes,[16] Sasaki correctly appreciated the U.S. commander's intent and responded quickly to the attack, moving troops to counter the flanking move, while in the forward areas movement was held up by Japanese snipers who concealed themselves in baskets in the trees and fired upon the U.S. troops with flashless rifles.[18] That day, the 172nd gained about 1,100 yards (1,000 m), while the 169th was unable to gain any ground at all.[16]

By 11 July, Hester decided to divert the 172nd Infantry Regiment to the south towards Laiana, while the 169th continued their advance up the Munda trail.[16] On the evening of 11/12 July, a naval task force under Rear Admiral Aaron S. Merrill, having departed Ironbottom Sound in the afternoon, fired over 8,600 shells during a 40-minute bombardment from the Blanche Channel to clear the jungle in front of the advancing troops; this ultimately proved ineffective, being fired over a mile in front of the U.S. troops for safety reasons. The following day, the 172nd resumed their advance but made only limited progress.[19] Allied efforts to interdict the Munda trail from the north proved unsuccessful,[20] and during this time the Japanese were able to land reinforcements from 16 barges that sailed from Vila; Japanese operations to move further reinforcements through the Slot on 12/13 July led to the naval Battle of Kolombangara.[6]

On 12 July, three battalions from the U.S. 169th Infantry Regiment carried out an attack against Japanese positions overlooking the junction of the Munda–Lambeti trail. The 1st and 2nd Battalions carried the attack initially, but were held up. The following day, the 3rd Battalion, 169th Infantry Regiment gained the south ridge—later dubbed "Reincke Ridge"—after several hours of fighting supported by dive bombers and artillery. A Japanese battalion found a gap in the line between the 169th and 172nd Infantry Regiments on 13 July, having resulted from the 172nd's diversion to Laiana, cutting off the American regiment around the high ground. They were then subjected to repeated counterattacks over the course of several days, resulting in over one hundred casualties on the first day alone.[21][22] The 172nd finally reached their objective at Laiana on 13 July, having found the going difficult to push through the swamp and coming under Japanese mortar fire. By the time they reached the beach, the regiment was running short of water and supplies. The following day, a second landing was carried out at Laiana, in an effort to shorten lines of supply and bring in reinforcements from the 3rd Battalion, 103rd Infantry Regiment, which linked up with the 172nd.[16]

As part of efforts to break through to the cut-off 169th, the U.S. Army 118th Engineers, having previously pushed a track from Zanana, bridged the Barike River and ran a jeep trail towards the 169th's lines. Japanese troops harassed the bulldozer operators throughout this effort.[23][24] Stores were moved to the head of this trail by an antitank company, but by 14 July it was still 500 yards (460 m) short. To relieve the supply situation, the 169th received supplies by parachute on 14 July. The following day, a battalion of the 145th Infantry Regiment arrived at Zanana as reinforcements, detached from the 37th Infantry Division.[25] The same day, the advancing U.S. troops reached the Japanese main defensive line, consisting of a line of pillboxes, bunkers and fighting positions, supported by light and heavy machine guns, mortars and mountain guns of varying calibers.[23] By this time many of the Americans were suffering from dysentery. As instances of combat stress began to rise fire discipline declined.[26]

At this time, U.S. commanders made plans for a coordinated offensive to take Munda, and requested further reinforcements. The preparations would take time, though, which the Americans sought to buy with harassing fire from artillery and air strikes, coupled with minor advances aimed at securing some of the trails between Laiana and Zanana to relieve the 169th. Around this time, the troops advancing on Munda were reinforced by six United States Marine Corps tanks from the 9th Defense Battalion. These went in to action by 16 July. At least four tanks were damaged over two days of fighting after becoming isolated from their infantry support and coming under attack by Japanese infantry armed with magnetic mines.[27][28]

Aftermath

The U.S. offensive made small gains because of the limited combat experience by its soldiers, poor leadership by inexperienced U.S. Army officers, harsh terrain and conditions on New Georgia, and effective defensive measures by the Japanese.[29][30] Casualties amongst the U.S. 43rd Division amounted to 90 men killed and 636 wounded; another 1,000 were evacuated due to illness. The U.S. soldiers experienced an unusually high number of severe cases of combat stress reaction.[25][18] In analyzing the battle, historian Samuel Eliot Morison assessed that the choice of Zanana as a landing site had been a mistake and that Hester's decision to send the 172nd Infantry Regiment south, thereby exposing the 169th, had also been ill considered, writing:

This was perhaps the worst blunder in the most unintelligently waged land campaign of the Pacific war (with the possible exception of Okinawa). Laiana should have been chosen as the initial beachhead; if it was now required, the 172nd should have been withdrawn from Zanana and landed at Laiana under naval gunfire and air support. Or Hester might have made the landing with his reserves then waiting at Rendova. As it was, General Sasaki interpreted the move correctly and by nightfall had brought both advances to a standstill.[18]

Author Mark Stille writes that the initial drive as resulting in "limited tactical progress" for the U.S. forces.[16] To break the deadlock, the U.S. command structure on New Georgia was reorganized. After carrying out an inspection of the situation and reporting back to Admiral William Halsey on Guadalcanal, the U.S. corps commander, Griswold, arrived to take overall command in the field, assuming this role at midnight on 15 July. While Hester retained command of his division, the regimental commander of the 169th Infantry Regiment—Colonel John Eason—was relieved of his command, being replaced by Colonel Temple Holland of the 145th Infantry Regiment. One of the 169th's battalion commanders was also relieved.[31][32] Meanwhile, supplies and reinforcements from the 161st Infantry Regiment (detached from the 25th Infantry Division), as well as tanks from the 10th Defense Battalion, were dispatched from Guadalcanal and the Russell Islands in preparation for a corps-level offensive. Before this could begin, though, the Japanese launched a counterattack on 17 July using the reinforcements that had arrived from Vila, effectively bringing the Allied drive on Munda temporarily to a halt. After this effort was defeated, the Americans eventually secured the airfield in the Battle of Munda Point in early August.[33][34][35]

Notes

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 69 (map)

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 201 (map)

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 73

- Rentz, Marines in the Central Solomons, p. 52

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, backcover

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 180

- Shaw & Kane, Isolation of Rabaul, p. 90

- Larsen, Pacific Commandos, pp. 9 & 108

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 92–94

- Rentz, Marines in the Central Solomons, p. 20

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 97

- Rottman, Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43, pp. 65–67

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 105

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 106

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, p. 52

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, p. 53

- Rottman, Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43, pp. 66–67

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 177

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 177–179

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, pp. 52–53

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 119

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 179, 198–199

- Hammel, Munda Trail, p. 104

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 114, 118, 120

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, p. 120

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 198

- Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 198–200

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 117–119

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, pp. 53–54

- Rottman, Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43, p. 67

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, p. 54

- Hammel, Munda Trail, p. 107

- Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, pp. 124, 137, 158–159

- Stille, The Solomons 1943–44, pp. 54–62

- Hammel, The Munda Trail, p. 123

References

- Hammel, Eric M. (1999). Munda Trail: The New Georgia Campaign, June–August 1943. Pacifica Press. ISBN 0-935553-38-X.

- Larsen, Colin (1946). Pacific Commandos: New Zealanders and Fijians in Action: A History of Southern Independent Commando and First Commando Fiji Guerrillas. Reed Publishing. OCLC 1135029131.

- Miller, John, Jr. (1959). "Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul". United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army. OCLC 494892065. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, vol. 6 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Castle Books. 0785813071.

- Rentz, John (1952). "Marines in the Central Solomons". Historical Branch, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. OCLC 566041659. Retrieved 30 May 2006.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Dr. Duncan Anderson (ed.). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43. Oxford and New York: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-870-7.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Douglas T. Kane (1963). "Volume II: Isolation of Rabaul". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. OCLC 80151865. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- Stille, Mark (2018). The Solomons 1943–44: The Struggle for New Georgia and Bougainville. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-47282-447-9.

Further reading

- Altobello, Brian (2000). Into the Shadows Furious. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-717-6.

- Craven, Wesley Frank; James Lea Cate. "Vol. IV, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, August 1942 to July 1944". The Army Air Forces in World War II. U.S. Office of Air Force History. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- Day, Ronnie (2016). New Georgia: The Second Battle for the Solomons. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253018773.

- Dyer, George Carroll. "The Amphibians Came to Conquer: The Story of Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner". United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- Feldt, Eric Augustus (1991) [1946]. The Coastwatchers. Victoria, Australia: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014926-0.

- Hayashi, Saburo (1959). Kogun: The Japanese Army in the Pacific War. Marine Corps. Association. ASIN B000ID3YRK.

- Hoffman, Jon T. (1995). "New Georgia" (brochure). From Making to Bougainville: Marine Raiders in the Pacific War. Marine Corps Historical Center. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- Horton, D. C. (1970). Fire Over the Islands. ISBN 0-589-07089-4.

- Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, Volume II – Part I. Reports of General MacArthur. United States Army Center of Military History. 1994. Retrieved 2006-12-08. – Translation of the official record by the Japanese Demobilization Bureaux detailing the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy's participation in the Southwest Pacific area of the Pacific War.

- Lofgren, Stephen J. Northern Solomons. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. p. 36. CMH Pub 72-10. Retrieved October 18, 2006.

- Lord, Walter (2006) [1977]. Lonely Vigil; Coastwatchers of the Solomons. New York: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-466-3.

- Melson, Charles D. (1993). "Up the Slot: Marines in the Central Solomons". World War II Commemorative Series. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. p. 36. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- Mersky, Peter B. (1993). "Time of the Aces: Marine Pilots in the Solomons, 1942–1944". Marines in World War II Commemorative Series. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved October 20, 2006.

- McGee, William L. (2002). The Solomons Campaigns, 1942–1943: From Guadalcanal to Bougainville--Pacific War Turning Point, Volume 2 (Amphibious Operations in the South Pacific in WWII). BMC Publications. ISBN 0-9701678-7-3.

- Radike, Floyd W. (2003). Across the Dark Islands: The War in the Pacific. ISBN 0-89141-774-5.

- Rhoades, F. A. (1982). A Diary of a Coastwatcher in the Solomons. Fredericksburg, Texas: Admiral Nimitz Foundation.