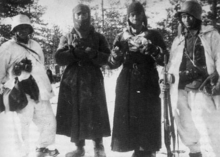

Soviet prisoners of war in Finland

Soviet prisoners of war in Finland during World War II were captured in two Soviet-Finnish conflicts of that period: the Winter War and the Continuation War. The Finns took about 5,700 POWs during the Winter War, and due to the short length of the war they survived relatively well.[1] However, during the Continuation War the Finns took 64,000 POWs, of whom almost 30 percent died.[2][Notes 1]

Winter War

The number of Soviet prisoners of war during the Winter War (1939–1940) was 5,700, of whom 135 died.[3] Most of them were captured in Finnish pockets (motti) north of Lake Ladoga.[4] The war lasted only 105 days and most of the deceased POWs were either seriously wounded or sick. Some of the POWs, at least 152 men, enlisted in the so-called Russian Liberation Army in Finland. They were not allowed to take part in combat. After the war, some members of the Liberation Army managed to escape to a third country.[5]

Continuation War

The number of Soviet prisoners of war during the Continuation War (1941–1944) was about 64,000. Most of them were captured in 1941 (56,000 persons).[2] The first Soviet POWs were taken in June 1941 and were transferred to reserve prisons in Karvia, Köyliö, Huittinen and Pelso (a village in modern-day municipality of Vaala). Soon Finnish administration realized that the number of POWs was much greater than initially estimated, and established 32 new prison camps in 1941–1944. However, all of them were not used at the same time as POWs were used as a labour force in different projects around the country.[6]

The Finns did not pay much attention to the living conditions of the Soviet POWs at the beginning of the war, as the war was expected to be of short duration. The quantity and quality of camp personnel was very low, as the more qualified men were at the front. It was not until the middle of 1942 that the quantity and quality of camp personnel was improved.[7] There was a shortage of labour in Finland and authorities assigned POWs to forest and agricultural work, as well as the construction of fortification lines.[8] Some Soviet officers cooperated with the Finnish authorities and were released from prison by the end of the war.[9]

Finnic prisoners who were captured on the fronts or transferred by Germany were separated from other Soviet POWs. At the end of 1942 volunteers could join the Finnish battalion Heimopataljoona 3, which consisted of Baltic Finns such as Karelians, Ingrian Finns, Votes and Veps.[10]

Prisoner exchange with Germany

About 2,600–2,800 Soviet prisoners of war were handed over to the Germans in exchange for roughly 2,200 Finnic prisoners of war held by the Germans. In November 2003, the Simon Wiesenthal Center submitted an official request to Finnish President Tarja Halonen for a full-scale investigation by the Finnish authorities of the prisoner exchange.[11] In the subsequent study by Professor Heikki Ylikangas it turned out that about 2,000 of the exchanged prisoners joined the Russian Liberation Army. The rest, mostly army and political officers, (among them a name-based estimate of 74 Jews), most likely perished in Nazi concentration camps.[12][13]

Deaths

Most of the deaths among Soviet POWs, 16,136, occurred in the ten-month period from December 1941 to September 1942. Prisoners died due to bad camp conditions and the poor supply of food, shelter, clothing, and health care. About a thousand POWs, 5 percent of total fatalities, were shot, primarily in escape attempts.[14] Food was especially scarce in 1942 in Finland due to a bad harvest. Punishment for escape attempts or serious violations of camp rules included solitary confinement and execution. Out of 64,188 Soviet POWs, from 18,318[15] to 19,085[3] died in Finnish prisoner of war camps.

In 1942 the number of prisoner deaths had a negative effect on Finland's international reputation. The Finnish administration decided to improve living conditions and allowed prisoners to work outside their camps.

Hostilities between Finland and the Soviet Union ceased in September 1944, and the first Soviet POWs were handed over to the Soviet Union on 15 October 1944. The transfer was complete by the next month.[16] Some of the POWs escaped during the transportation, and some of them were unwilling to return to the Soviet Union. Furthermore, Finland handed over 2,546 German POWs from the Lapland War to the Soviet Union.[17]

Trials in Finland

According to the Moscow Armistice, signed by Finland and the victorious Allies, mainly the Soviet Union, the Finns were to try those who were responsible for the war and those who had committed war crimes. The Soviet Union allowed Finland to try its own war criminals, unlike other losing countries of the Second World War. The Finnish parliament had to create ex post facto laws for the trials, though in the case of war crimes the country had already signed the Hague IV Convention.[18] In victorious Allied countries war-crime trials were exceptional, but Finland had to arrange full-scale investigations and trials, and report them for the Soviet Union.[19]

Criminal charges were filed against 1,381 Finnish POW camp staff members, resulting in 723 convictions and 658 acquittals. They were accused of 42 murders and 342 other homicides. Nine persons were sentenced to life sentences, 17 to imprisonment for 10–15 years, 57 to imprisonment for five to ten years, and 447 to imprisonment varying from one month to five years. Fines or disciplinary corrections were levied out in 124 cases.[20] Although the criminal charges were highly politicized, some war crime charges were filed already during the Continuation War. However, most of them were not processed during wartime.[21]

Aftermath

Winter War POWs Returned to the Soviet Union

After the Winter War, the Soviet POWs were returned to the USSR in accordance with the Moscow Peace Treaty. They were transported under heavy guard by the NKVD to special camps as suspected traitors. Prisoners were interrogated by 50 person research teams. After lengthy investigations about 500 of the prisoners were found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death. Some prisoners were released, but most of them, 4,354 men, were sentenced to five to eight years in labour camps (gulag). This would lead to the later death of some of the prisoners due to harsh camp conditions.[22]

Continuation War POWs Returned to the Soviet Union

After the Continuation War, Finland handed over all Soviet and German prisoners of war in accordance with the 10th article of the Moscow Armistice. Furthermore, the article also stipulated the return of all Soviet nationals who were deported to Finland during the Continuation War. This meant that Finland also had to hand over all those who moved to Finland voluntarily, as well as those who fought in the ranks of the Finnish army against the Soviet union, though some had Finnish citizenship. The return to the Soviet Union was in many cases fatal for these people, as some of them were executed as traitors at the Soviet train station at Vyborg and some died in harsh camp conditions in Siberia.[9][23] After the collapse of the Soviet Union the survivors were allowed to return to Finland.[23]

Some of the Soviet prisoners of war co-operated with the Finns during the war. Before the end of the war all related Finnish archives, including interrogation documents relating to co-operating prisoners, were destroyed; and these POWs' destinations after the war are uncertain. Some of them were secretly transported by Finnish army personnel to Sweden and some continued on as far as the United States.[1] The highest ranking Soviet prisoner of war was Major General Vladimir Kirpichnikov, who returned to the Soviet Union. He was tried, convicted of high treason, and executed in 1950.[24]

Legal position of Soviet POWs

Finland had signed the 1907 Hague IV Convention in 1922 that covered the treatment of prisoners of war in detail. However, Finland announced that it could not completely obey the convention as the Soviet Union had not signed the same convention. The convention required ratification by both parties to the hostilities before going into effect.[25] Finland did not sign the updated 1929 Third Geneva Convention, because it conflicted with some clauses of Finnish criminal law. Although the Soviet Union had not signed the Hague IV Convention, the reality was unclear and ambiguous.[26] Soviet law specified that a Soviet soldier's surrender constituted treason which was punishable by death or imprisonment and seizure of the soldier's property.[27]

See also

Notes

- According to the 1953 official Finnish report there were 64,188 Soviet POWs in Finland of whom 18,700 died. According to the 2008 database of the National Archives of Finland the number of deaths are 19,085. However, Finnish historian Antti Kujala calculated in his book "Vankisurmat" (2008), pp. 310–311, that the number of Soviet POWs was about 67,000 of whom about 22,000 died (including about 3,000 unregistered POWs).

References

Citations

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Kujansuu, Juha (2005), p. 1045

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Kujansuu, Juha (2005), p. 1036

- Westerlund (2008), p. 8

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Manninen, Ohto (1999), p. 812

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Manninen, Ohto (1999), p. 814

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Kujansuu, Juha (2005), p. 1033

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Kujansuu, Juha (2005), p. 1037

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Kujansuu, Juha (2005), p. 1038

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Kotro, Arto (2005), p. 314

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Kujansuu, Juha (2005), p. 1039

- The Simon Wiesenthal Center, press information

- Jakobson, Max (16 November 2003). "Wartime refugees made pawns in cruel diplomatic game". Helsingin Sanomat. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- Ylikangas, Heikki, Heikki Ylikankaan selvitys Valtioneuvoston kanslialle Archived 8 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Government of Finland

- Westerlund (2008), p. 9

- Ylikangas, Heikki (16 January 2004). "Heikki Ylikankaan selvitys Valtioneuvoston kanslialle" (PDF) (in Finnish). Valtioneuvosto kanslia / Finnish Council of State. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Kujansuu, Juha (2005), p. 1040

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Kujansuu, Juha (2005), p. 1041

- Kujala (2008), p. 24

- Kujala (2008), p. 11

- Westerlund (2008), p. 16

- Kujala (2008), p. 25

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Manninen, Ohto (1999), p. 815

- Juutilainen & Leskinen (ed.); Nevalainen, Pekka (2005), p. 117

- Westerlund (2008), p. 555

- Kujala (2008), p. 151

- Kujala (2008), p. 152

- Kujala (2008), p. 154

Bibliography

- Kujala, Antti (2008). Vankisurmat : neuvostosotavankien laittomat ampumiset jatkosodassa (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö. p. 332. ISBN 978-951-0-33761-5.

- Leskinen, Jari; Juutilainen, Antti, eds. (2005). Jatkosodan pikkujättiläinen (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö. p. 1259. ISBN 951-0-28690-7.

- Leskinen, Jari; Juutilainen, Antti, eds. (1999). Talvisodan pikkujättiläinen (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö. p. 976. ISBN 951-0-23536-9.

- Westerlund, Lars, ed. (2008). Prisoners of War and Internees: A Book of Articles by the National Archives / Sotavangit ja internoidut: Kansallisarkiston artikkelikirja (PDF) (in English and Finnish). National Archives of Finland. p. 568. ISBN 978-951-53-3139-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-15.