North Shanxi Autonomous Government

The North Shanxi Autonomous Government (also known as the Jinbei Autonomous Government; Chinese: 晋北自治政府; pinyin: Jìnběi zìzhì zhèngfǔ; Wade–Giles: Chin4-pei3 tzu4-chih4 cheng4-fu3; Hepburn: Susumu kita jichi seifu) was an administratively autonomous component of Mengjiang from its creation in 1937 to its complete merger into Mengjiang in 1939. Following the Japanese invasion of China in July 1937, regional governments were established in Japanese-occupied territories. After Operation Chahar in September 1937, which extended Japanese control to northern Shanxi region, more formal control of the area was established through the creation of the North Shanxi Autonomous Government, as well as the South Chahar Autonomous Government to the east of Shanxi.

North Shanxi Autonomous Government | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1937–1939 | |||||||||

Flag

Government seal

| |||||||||

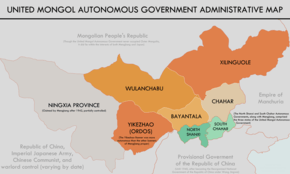

A map of the United Mongol Autonomous Government featuring the state | |||||||||

| Status | Administratively autonomous component of Mengjiang | ||||||||

| Capital | Datong | ||||||||

| Common languages | Chinese (common) Mongolian Japanese | ||||||||

| Government | Civil administration | ||||||||

| Supreme Adiviser | |||||||||

• 1937-1939 | Maejima Masu | ||||||||

| Supreme Council Member of the Mengjiang United Committee | |||||||||

• 1937–1939 | Xia Gong | ||||||||

| Historical era | Occupation of China in the Second Sino-Japanese War | ||||||||

| 15 October 1937 | |||||||||

• Merger into the Mongol United Autonomous Government | 1 September 1939 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1937 | 14,102 km2 (5,445 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1939 | 1,500,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Multiple currencies, see Economics | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Although Mengjiang at first only exerted a supervisory and directing role over the North Shanxi Autonomous Government by means of the Mengjiang United Committee, a conference of influential figures from the North Shanxi Autonomous Government, the South Chahar Autonomous Government, and Mengjiang; the influence exerted by Mengjiang over time allowed for greater and greater control over the affairs of the area, causing it to lose its administrative autonomy in 1939 through the formation of the United Mongol Autonomous Government.

Name

The North Shanxi Autonomous Government is referred to by multiple names in English, though is commonly referred to by a single name in Chinese. The full Chinese name for the state is 晋北自治政府 (pinyin: Jìnběi zìzhì zhèngfǔ; Wade–Giles: Chin4-pei3 tzu4-chih4 cheng4-fu3), literally meaning "Shanxi North/Northern Autonomous Government". This name makes use of the Chinese character 晋 (pinyin: jìn; Wade–Giles: jin4) to refer to Shanxi, rather than its full name, 山西 (pinyin: Shānxī; Wade–Giles: Shan1-hsi1). Because of this, the term 晋北 (pinyin: Jìnběi; Wade–Giles: jin4-pei3; lit.: 'Jin [Shanxi] North') is sometimes left untranslated in English as "Jinbei", rather than as "North/Northern Shanxi".[2]

The state is also referred to by different names in other languages, such as the Mongolian ᠤᠮᠠᠷᠠᠲᠤᠱᠠᠨᠢᠰᠢᠠᠦ᠋ᠲ᠋ᠣᠨᠣᠮᠢ ᠳᠤᠵᠠᠰᠠᠭ ᠤᠨᠭᠠᠵᠠᠷ(Cyrillic: Умард Шаньси Автономит засгийн газар), though, this is uncommon.

Background

Following the Marco Polo Bridge incident and Japan's descent into war with China, Japanese plans for their (hoped) victory in the Second Sino-Japanese War were prepared and began to be acted upon.[3] Among these plans, particularly early on in the war, involved the administration of China by means of dividing it into many smaller buffer states, all under the Japanese sphere of influence.[4] By 1938, multiple smaller Japanese-aligned governments existed throughout China aside from the more-major puppet states of Manchukuo and Mengjiang. Some of these then-newly created administratively autonomous Japanese puppet states included the East Hebei Autonomous Government,[5] the Shanghai Great Way Government,[6] the South Chahar Autonomous Government, and of course, the North Shanxi Autonomous Government.

Creation

On the morning of September 13, 1937, the city center of Datong was captured by Japanese army forces, and was placed under military control for the time being. Soon after, however, a group of influential figures from the city including Wang Yongkui, the president of the Datong City Chamber of Commerce, a middle school teacher, an accountant, and others welcomed the Japanese, with they themselves posing little resistance to the occupation. Later that month on September 20, the foundations of the area's collaborationist government were established with the North Shanxi Public Security Maintenance Center in Datong. Leading this effort at first was Chen Yuming, who was brought by the Japanese army from Zhangjiakou (Kalgan), the then-capital of Mengjiang, to direct Datong's administration. Under Chen, the North Shanxi Public Security Maintenance Center formed a militia force of 150 citizens from Datong in cooperation with the Japanese Army for the city's own defense. Chen's administration of Datong was cut short, however, by the restructuring of the entire region's governance in October.[7]

In October, the Japanese army hosted a conference whose stated aim was to "Bring the Shanxi Province to Autonomy", which was held in the Gulou West Street Theater in Datong. At this conference, whose attendance numbered over a thousand, the administrative capacity of the North Shanxi Public Security Maintenance Center was superseded by various other administrative organs, leading to the plans for the creation of an autonomous state in northern Shanxi, with its capital in Datong, to be put into motion by the Japanese army.

On October 15, 1937, the North Shanxi Autonomous Government was officially created.[8]

Governance

In terms of international relations, the North Shanxi Autonomous Government was not recognized by any sovereign states. Even Japan itself did not officially recognize the North Shanxi Autonomous Government as a nation. Mengjiang however, and the neighboring South Chahar Autonomous Government did, however. These three states, Mengjiang, North Shanxi, and South Chahar, were all bound by means of the Supreme Council, an organization based in Zhangjiakou directing (but not enforcing or creating) the policy of all three states. Mengjiang, however, exerted by far the most influence inside the Mengjiang United Committee, allowing for the other two states to become yet more dependent on and integrated to Mengjiang as time went on.[9] Representing the North Shanxi Autonomous Government at the Mengjiang United Committee was Xia Gong, a former local politician during the Republic of China's control of Shanxi.[10]

To keep the North Shanxi Autonomous Government inline with Japanese interests, the position of Supreme Adviser was created above all other positions within the state's governance. This position was filled by Maejima Masu, an ethnically Japanese political figure who had previously worked in local management in Manchukuo.[11]

The government of the North Shanxi Autonomous Government itself consisted of multiple departments, all under the control of Maejima Masu, the Supreme Adviser.[7]

Structure of the North Shanxi Autonomous Government

Advisory and Leading Figures

- Supreme Adviser: Maejima Masu

- Supreme Council Member of the Mengjiang United Committee: Xia Gong

- Members of the Mengjiang United Committee: Ma Yongkui, Chi Weiting, Gu Xiyu, Wen Huajun (later replaced by Wang Shouxin)

- Official Consultant: Oba Masaaki

- Spokesperson to the Supreme Adviser: Oba Masaaki

- Supreme Council Member of the Mengjiang United Committee: Xia Gong

Departments

- Department of Civil Health:

- Director: Lu Dengyu (later replaced by Dennanji Hitsu)

- Consultant: Iwasaki Tsugisei

- Department of Finance:

- Director: Cui Xiaoqian

- Consultant: Hashimoto Otoji

- Department of Police:

- Director: Mori Ichirō[12]

Economics

The region of North Shanxi contains vast deposits of coal south of the capital Datong.[13] These deposits of resources would help form an economic foundation for North Shanxi under Japanese control despite the smaller size of the North Shanxi Autonomous Government compared to other states, such as Mengjiang. Due to the Japanese oversight of the state, as well as its economics, much of North Shanxi's coal was diverted to Japanese war efforts during this time. According to a Japanese correspondent of the Oriental Economist (via the Far Eastern Survey),

All lines of political and economic enterprise have been placed in the hands of officials who were transferred from the civil and other services in Manchoukuo[14]

Supporting this remark, systems of organization from Manchukuo began to be implemented in North Shanxi, as well as the rest of Mengjiang, along with the movement of experienced individuals from Manchukuo. Chief among these new organizations was the Labor Control Committee of North Shanxi (Chinese: 晋北勞働統制委員會; pinyin: Jìnběi láodòng tǒngzhì wěiyuánhuì; Wade–Giles: Chin4-pei3 lao2-tung4 t'ung3-chih4 wei3-yüan2-hui4), founded on May 29, 1939. In Manchukuo previously, Japanese organizations had been placed in charge of labor and manpower to support Japan's war interests, even outside Japan proper. These projects in Manchukuo would be quite successful, creating an example of how war prisoners, as well as native Chinese and other ethnicities' populations could be forced into labor while simultaneously allowing more ethnically Japanese manpower for the Imperial Japanese Army itself.

Citing acute labor shortages[15] and lackluster profits from coal production,[14] a group of 8,000 Chinese laborers were pressed into coal mining operations by mid-1939. The 8,000 Chinese laborers were put into groups of 1,000, with each group working a three-month shift. The Labor Control Committee quickly became a valuable organization for the North Shanxi Autonomous Government, letting them increase their profits from coal sale not by increasing the long-standing tax of 15 sen per ton,[14] but instead by simply extracting more coal with less money spent on the care of workers at the Datong mines.[15]

Currency

In the North Shanxi Autonomous Government, there was no single legal currency. Instead, the currencies of Japan, Mengjiang, the Republic of China, South Chahar, and the banks of North Shanxi were all used in conjunction.[16] Most of the larger banks of North Shanxi produced their own banknotes, which were used in official settings. Due to the circulation of so many currencies even in official uses, the government stamps of North Shanxi are often seen on government paperwork, such as tax documents. Even on some government tax documents however, payment is conducted in other states' currencies, such as that of the South Chahar Autonomous Government.[17]

National Banks

The largest bank of North Shanxi was Shansi Provincial Bank, established in 1919. The bank had a capital of 12,000,000 Chinese yuan in 1940, five times the national earnings from the entire coal industry the year before. Other major banks in North Shanxi at this time included the Bank of Local Railways of Shansi and Suiyuan (10,000,000 Yuan capital), the Sui-Hsi Farmer's Bank (600,000 yuan capital), and the Shansi Provincial Salt Bank (2,000,000 yuan capital).[16]

Merger into Mengjiang

As time went on and the relationship between the North Shanxi Autonomous Government and Mengjiang became ever closer and closer, the two states, along with the South Chahar Autonomous Government, would merge together to form the Mengjiang United Mongol Autonomous Government. On September 1, 1939, the status of the North Shanxi Autonomous Government was changed as it lost its autonomous administration, to become a much more directly controlled part of Mengjiang itself. Though North Shanxi would still have a relative amount of autonomy, this as well was removed in 1943 when it was reformed into the Datong Provincial Office of Mengjiang.[12]

Gallery

The entrance to the North Shanxi government building

The entrance to the North Shanxi government building A view of a street in Japanese-occupied Datong

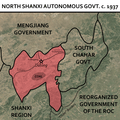

A view of a street in Japanese-occupied Datong A map of the state highlighting its location next to other states, such as the South Chahar Autonomous Government

A map of the state highlighting its location next to other states, such as the South Chahar Autonomous Government Chinese soldiers in Shanxi in October 1937, the month when the North Shanxi Autonomous Government was established

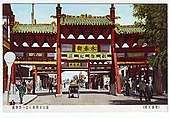

Chinese soldiers in Shanxi in October 1937, the month when the North Shanxi Autonomous Government was established A postcard of a gate in Japanese-occupied Datong

A postcard of a gate in Japanese-occupied Datong

See also

- Mengjiang

- South Chahar Autonomous Government

- Great Way Government

- Provisional Government of the Republic of China

- Inner Mongolian People's Republic

References

- "晋北自治政府" [North Shanxi Autonomous Government]. Knowledge Shell (in Chinese). Retrieved 27 Aug 2019.

- Narangoa, Li; Cribb, Robert; Cribb, R. B. (2003). Imperial Japan and National Identities in Asia, 1895-1945. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780700714827.

- Morton, Louis. "Japan's Decision for War". U.S. Army Center Of Military History. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Boyle, John H. (1972). China and Japan at War, 1937-1945; The Politics of Collaboration. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804708002.

- Shizhang Hu (1 January 1995). Stanley K. Hornbeck and the Open Door Policy, 1919-1937. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 213–. ISBN 978-0-313-29394-8.

- Henriot, Christian; Yeh, Wen-hsin (2004-04-12). In the Shadow of the Rising Sun: Shanghai Under Japanese Occupation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521822213.

- "日伪晋北自治政府的成立" [The Establishment of the Japanese Puppet North Shanxi Autonomous Government]. blog.sina.com.cn (in Chinese). 27 Sep 2018. Retrieved 27 Aug 2019.

- "「烽火张垣」伪蒙疆政权——晋北自治政府(三)" ["Fenghuo Zhangyuan" The Pseudo-Mongolian North Shanxi Autonomous Government's Regime (3)]. www.sohu.com (in Chinese). Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- Datong City Civil Affairs Bureau (1983). 大同市从古至今的历史 [The History of Datong City from Ancient Times to the Present]. Shanxi People's Publishing House. pp. 130–138.

- Committee for Problems of East Asia (東亜問題調査会) (1941). The Biographies of Most Recent Chinese Important People (最新支那要人伝). Asahi Shimbun.

- 山西通志: 政务志·政府篇 [Shanxi Tongzhi: Administrative Affairs and Government]. Beijing, China: Zhonghua Publishing. pp. 278–279.

- 山西文史资料56 [Shanxi Literature and History Materials 56]. Taiyuan, China: Shanxi People's Publishing House. 1988. pp. 45–47.

- Huang, Wenhui; Zhang, Kuangming; Tang, Xiuyi; Zhao, Zhigen; Wan, Huan (2010). "Coking coals potential resources prediction in deep coal beds in Northern China". Energy Exploration & Exploitation. 28 (4): 313–325. doi:10.1260/0144-5987.28.4.313. ISSN 0144-5987. JSTOR 26160906.

- Hanwell, Norman D. (1939). "Japan's Inner Mongolian Wedge". Far Eastern Survey. 8 (13): 147–153. doi:10.2307/3021726. ISSN 0362-8949. JSTOR 3021726.

- Kratoska, Paul H. (2014-12-18). Asian Labor in the Wartime Japanese Empire: Unknown Histories: Unknown Histories. Routledge. ISBN 9781317476429.

- Tokunaga, Kiyoyuki (1940). "The Progress of Monetary Unification in the Meng Chiang Provinces". Kyoto University Economic Review. 15 (1 (31)): 30–44. ISSN 0023-6055. JSTOR 43216843.

- Qingdao Jiujingzhai. "晋北自治政府-牲畜税票" [North Shanxi Autonomous Government - Livelihood Tax Pass]. 7788 Shoucang (in Chinese). Retrieved 31 Aug 2019.