Romanian anti-communist resistance movement

The Romanian anti-communist resistance movement was active from the late 1940s to the mid-1950s, with isolated individual fighters remaining at large until the early 1960s. Armed resistance was the first and most structured form of resistance against the communist regime, which in turn regarded the fighters as "bandits". It was not until the overthrow of Nicolae Ceaușescu in late 1989 that details about what was called "anti-communist armed resistance" were made public. It was only then that the public learnt about the several small armed groups, which sometimes termed themselves "haiducs", that had taken refuge in the Carpathian Mountains, where some hid for ten years from authorities. The last fighter was eliminated in the mountains of Banat in 1962. The extent and influence of the movement is often exaggerated in the post-Communist Romanian media, memoirs of the survivors and even historiography, while the authoritarian, anti-Semitic and/or xenophobic ideology of part of the groups is generally overlooked or minimized.[1] The Romanian resistance was one of the longest lasting armed movements in the former Soviet bloc.[2]

| Romanian anti-communist resistance movement | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Eastern European anti-Communist insurgencies | |||||||

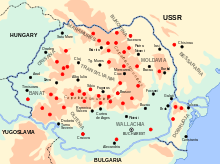

Map of Romania with armed resistance areas marked in red | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Full list below. |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000 rebels | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~2,000 killed | Unknown, but most likely light | ||||||

| Eastern Bloc | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

|

Allied states

|

|||||||

|

Related organizations |

|||||||

|

Dissent and opposition

|

|||||||

Preliminaries

In March 1944, the Red Army set foot in Bukovina, advancing into Romania, at the time an ally of Nazi Germany. Hundreds of people went into the forests forming anti-Soviet guerrilla groups of 15–20 people.[3]

After the Allied armistice with Romania (11–12 September 1944), the Red Army had free run in Romania and the Romanian government did not have authority over Northern Bukovina. In late 1944 and early 1945, some small armed groups were formed in Romania, with a mission of harassing the Red Army in a future war between the Soviets and the West.[3] After the war, most of these groups dissolved while others remained in the mountains until 1948, when they became active. In May 1946, General Aurel Aldea, the former Minister of the Interior of the Sănătescu government, was arrested and charged with "bringing together various subversive organisations under his command". It appears, however, that the "National Resistance Movement", which he coordinated, posed little threat, if any, to the establishment of the communist regime.

After the elections of 1946, a coalescence of anti-communist forces led to a structure reuniting generals, senior officers and politicians preparing and coordinating armed groups under a single command.[4] The central coordinating structure inside Romania reported on this initiative to the Romanian National Council residing in Paris, which in turn informed the Western governments. The project was eventually intercepted by the Romanian authorities, which subsequently carried out massive arrests in spring 1948, comprising up to 80% of those who were implicated in the movement. Thus, the coordinated national resistance was decapitated.

Onset of the armed resistance movement

However, starting with the summer of 1948, individuals or small groups went underground in the Carpathians, forming various units of armed resistance in what was a relatively large movement, gathering several thousand people. The rebels came from all social strata and all areas of the country, spreading everywhere the terrain could shield them. The movement was related to the spate of mass arrests hitting the country after the communists seized power on 30 December 1947, as well as to the political and economical measures which ruined a sizable part of the peasantry and the middle class.[5]

There were several reasons for people seeking shelter in the mountains. While some went underground to escape imminent arrest, more generally people fled as they abandoned hope for surviving after being economically ruined and risking detention or worse. Significantly, entire families took flight in late 1948 and early 1949. Thus, the British consular official in Cluj, reporting on 1 May 1949 on the situation of partisans under the leadership of General Corneliu Dragalina noted that:

clothing and medicine are short and this is probably true as their numbers have been increased by a considerable proportion of women and children since the March 1st land expropriation. I have been given a figure as high as 20,000 as the number who has joined since the expropriation (…) The increase in the number of women and children will create problems of survival next winter (…) I am told now and again of lorries of army supplies going over to the partisans, sometimes by capture and sometimes by desertion, but I cannot say to what extent…"[4]

The members of the armed resistance were not called "partisans" by the population, but haiduci,[6] a word for generous highwaymen, considered folk heroes.

A further major component of the armed resistance consisted of individuals and groups motivated by anti-communist convictions and persuaded that only an armed engagement could contain increasing terror and prevent an irrevocable communist takeover. Some of the resistance groups were led by ex-army officers and acted in a more coordinated and planned way. It appears that they put their hope in stirring up a more general armed insurrection, which never came to life. A smaller category of insurgents were Romanian refugees recruited in Europe by the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC), trained in France, Italy, and Greece and then dropped in the Carpathians. It seems, however, that most of them, not being able to create local contacts imperative for survival, were soon captured.[4]

The rebels had links with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which conducted parachute missions in Romania in the early post-war years. At the beginning of 1949, the CIA through its Office of Policy Coordination (OPC) began to recruit displaced Romanians from West Germany, Austria, and Yugoslavia. Gordon Mason, the CIA station chief in Bucharest from 1949 to 1951, said that the smuggling of weapons, ammunition, radio transmitters, and medicine were organized. Agents smuggled into Romania by the CIA were to help organize the sabotage of factories and transport networks. In particular, a two-man team was parachuted into Romania by the CIA on 2 October 1952 near Târgu Cărbunești in Oltenia. Three American-trained agents were sent in June 1953 to the Apuseni Mountains; they were later captured, but not executed, as the Romanian authorities intended to use them as double agents. In the Oradea-Satu Mare region, three airdropped agents were killed, one of them in a firefight and two others later executed.[7]

Among the Romanians recruited by the CIA at the beginning of 1951 were Constantin Saplacan, Wilhelm Spindler, Gheorghe Bârsan, Matias Bohm, and Ilie Puiu. The Securitate discovered that these men had been recruited in Italy by a former Romanian pilot. Following this, the Romanian Government sent a note to the United States protesting interference in the country's internal affairs, and that the captured CIA agents had been "sent to carry out acts of terrorism and espionage against the Romanian Army."[8]

Resistance groups

Ion Gavrilă-Ogoranu, a member of the Iron Guard's youth wing who led a resistance group in the Făgăraș Mountains from 1948 to 1956, and remained undetected until 1976, worked out a set of defining traits of the typical Romanian resistance group.[9] According to this author, such a group was rather small, but could number up to 200 men, located in a mountainous/forested area which comprised some communities. Ogoranu further claimed that such groups were supported by a significant number of inhabitants (up to several thousands), who provided shelter, food and information.

In the Apuseni region of Transylvania, the most active group was led by Leon Șușman. The group mainly hid in the woods and acquired part of its armament from an Iron Guard band that the Germans parachuted in the area in 1944–45. To eliminate this resistance group, the Securitate used informers against them and intercepted the correspondence of family members.[10] An armed group called "The National Defense Front-The Haiduc Corps" was headed by a former officer of the Royal Army who participated in the war against the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front, Major Nicolae Dabija. Resistants from this group robbed the Tax Office in Teiuș, armed with a rifle and handguns. The Securitate learned about the location of this group after an arrested resistant revealed their location on Muntele Mare and about their strength. An operation conducted by the Securitate forces decided to attack the rebels on the morning of 4 March 1949. Securitate forces led by Colonel Mihai Patriciu charged the peak where the rebels were located, with a gunfight and later hand-to-hand combat occurring. The Securitate suffered three deaths and three others wounded. Dabija was arrested on 22 March 1949 after a local villager, whose barn he was sleeping in, notified the authorities of his presence. On 28 October 1949, seven members of the group, including Major Nicolae Dabija, were executed in Sibiu.[11]

Resistance groups were the target of systematic and enduring military actions from fully armed regular troops of the Securitate. The strength of the Securitate troops could vary from platoon to battalion up to regiment, including armoured vehicles, artillery and occasionally even aviation. The insurgent groups sustained losses consisting of dead and wounded captured by the Securitate. They also fell victim to treason from supporters or infiltrated persons, which led to losses and captures. Gavrilă-Ogoranu claims that some of the arrested rebels and their supporters were killed during interrogation, while other members of resistance groups were indicted in public or secret trials, and sentenced to death or prison. He estimates that several thousands of convictions were imposed. Capital punishment was carried out - either secretly, with bodies thrown into unknown common graves, or publicly in order to intimidate the local population. A significant number of detained rebels, who had not been sentenced to death, were killed outside prisons, under unexplained circumstances. In areas where the rebels were active, the population underwent systematic intimidation and terror from the authorities.

Structure and function

Dispersal, extent, and duration of the resistance rendered research after 1990 more difficult in ascertaining structural information on the movement. Evaluating the archives of the Securitate the CNSAS (National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives) has assessed a provisional figure of 1196 resistance groups acting between 1948 and 1960.[12] The size of the groups varied from small groupings of less than 10 members to intermediate sized groups counting around 40 fighters up to larger detachments of more than 100 men, with the highest distribution density placed around a strength of 15–20 men.[4][9] According to these assumptions, the total number of active resistance fighters may not fall below 10,000 persons, with an estimated figure of at least 40–50,000 supporting persons.[12] The number of killed victims on the insurgents' side could be established according to both archive data and various memoirs published after 1990. The archives revealed several hundreds of death penalties, yet a much larger number of resisters have been killed either in battle or during different phases of detention.[13] An estimated figure could amount 2,000 lost lives.

The social structure of the insurgent groups was heterogeneous, comprising a considerable part of peasants, many students and intellectuals as well as several army officers.[4] A report of the Securitate from 1951 containing information on 804 arrested resistance members ranking among 17 "mountain bands" reveals following political affiliation: 11% National Peasants' Party, 10% Ploughmen's Front, 9% Iron Guard, 5% Communist Party, 2% National Liberal Party.[4]

List of major resistance groups

The territorial structure of the resistance covered mainly the mountainous and heavy forested parts of the country. A list of some of the most important resistance groups and their location:[14][15]

| Area | Name of the group/group leader |

|---|---|

| Maramureș [16] | Gavrilă Mihali-Ștrifundă; Vasile Popşa; Ilie Zubașcu; Ion Ilban; Nicolae Pop; Vasile Dunca; group of Uniate priests |

| Rodna Mountains | "Cross and Sword Organization" (Leonida Bodiu) |

| Bucovina [17][18][19] | Constantin Cenușă,[3] Vasile Motrescu; Col. Vasile Cârlan; Grigore Sandu; Vasile Cămărușă; Silvestru Harsmei; Gavril Vatamaniuc; Ion Vatamaniuc,[3] Vladimir Macoveiciuc,[3] Petru Maruseac,[3] Sumanele Negre,[3] Tinerii Partizani ai României.[3] |

| Suceava | Silvestru Hazmei; "Decebal's Guards" (Gǎrzile lui Decebal),[20] Ion Chiraș and Gheorghe Chiraș.[3] |

| Crișul Alb River and Arad | Valer Șirianu; "National Liberation Movement"; Adrian Mihuțiu; Gligor Cantemir;[21] Ion Lulușa; |

| Bistrița-Năsăud | Haiducii lui Avram Iancu [22][23] |

| Apuseni Mountains | "White Army" (Capt. Alexandru Suciu); "National Defence Front – Hajduk Corps" (Maj. Nicolae Dabija – brothers Macavei);[24][25] Dr. Iosif Capotă -Dr. Alexandru Dejeu; Teodor Șușman;[26] Ioan Robu; Ștefan Popa; Ioan Crișan – Leon Abăcioaiei; Sandu Maxim; brothers Spaniol; "Cross and Sword Organization"; Acft. Capt. Diamandi Ionescu |

| Cluj[27] | Gheorghe Pașca; Alexandru Podea; Pop; Maj. Emil Oniga; Cornel Deac |

| Bacău | Vasile Corduneanu; Uturea group (Gheorghe Ungurașu, Petre Baciu) |

| Banat [28][29][30][31] | Col. Ion Uţă;[32] Spiru Blănaru; Aurel Vernichescu; Acft. Cdr. Petru Domășneanu; Nicolae Popovici; Gheorghe Ionescu; Petru Ambruș; "Great Romania Partisans"; brothers Blaj; Ion Tănase; Dumitru Isfănuț (Sfârlogea); Nicolae Doran; Ion Vuc |

| Hunedoara | Lazăr Caragea; Petru Vitan |

| Sibiu | resistance point Fetea |

| Covasna | "Vlad Ţepeș Organisation" (Victor Lupșa, Corneliu Gheorghe-Szavras) |

| Braşov [33] | "Vlad Țepeș Organisation" [34] |

| Vrancea [35] | Vrancea group (brothers Paragină); Gheorghe Militaru; "Vlad Țepeș Organisation"; (Victor Lupșa); Acft. Capt. Mândrișteanu |

| Bârlad | Constantin Dan |

| Northern Făgăraş Mountains [36] | Dumitru (Ionele Ion); Făină; Ion Cândea; Grupul Carpatin Făgărășan (Ion Gavrilă Ogoranu) |

| Southern Făgăraș Mountains [36] | Col. Gheorghe Arsenescu; Haiduks of Muscel (brothers Petru and Toma Arnăuţoiu);[37] Apostol; Șerban-Voican group in Muscel area between 1951–1957;[38] |

| Gorj | Capt. Mihai Brâncuși |

| Vâlcea | Gheorghe Pele; Şerban Secu; Ion Jijie |

| Craiova | Gen. Ioan Carlaonț; Marin Dumitrașcu |

| Dobrogea [39][40] | Gheorghe Fudulea; brothers Croitoru; Gogu Puiu; Nicolae Ciolacu; Niculae Trocan; Dobrogea's Haiducs |

Rather than a planned action, the resistance movement was a spontaneous reaction in response to the wave of terror initiated by the authorities after the seizure of power in early 1948.[41] The spontaneous nature of the movement explains its marked fragmentation and the lack of coordination between the resistance groups. However, acting isolated and on a local basis conferred the groups a multiformity and flexibility which rendered the annihilation of the entire movement more difficult, and ensured a remarkable staying power for some groups. Furthermore, in some areas a notable reproducibility occurred, exterminated groups being replaced by new cores of resistance.

A characteristic trait of the movement was its defensive nature. Indeed, few offensive actions such as sabotages or occupation of localities have been recorded.[41] While the groups did not pose a major material threat to the authorities, their dangerousness for the regime resided in the symbol they represented: as long as the resisters remained free, they created a tangible challenge to the regime's claim of exercising total control over the country.[42]

Repression

The Romanian security forces succeeded in defeating rebel forces due to coordination between the Securitate and militia forces, as well the penetration of the insurgent groups with the use of informers, intelligence gathering, and persuasion.[43]

Adriana Georgescu Cosmovici was one of the first people to be arrested for belonging to the resistance movement. In July 1945, the 28-year-old woman was arrested in Bucharest, and severely beaten by the secret police investigators.[44] In a statement made in Paris in 1949, she named three investigators as having threatened her with guns, one of them being Alexandru Nicolschi.[44] According to a 1992 article for Cuvântul, Nicolschi ordered the murder of seven prisoners (allegedly the leaders of an anti-communist resistance movement) in transit from Gherla Prison in July 1949.[44]

Elisabeta Rizea and her husband, two peasants opposed to the government's policy of forced collectivization, joined the guerrilla group "Haiducii Muscelului" led by Colonel Gheorghe Arsenescu, providing food and supplies. Caught in 1952, she served 12 years in prison, during which time she was subjected to torture.

On 18 July 1958, Vasile Motrescu was executed. In 1959, 80 people led by Vasile Blănaru were tried for "armed insurrection" in the area of Câmpulung Muscel.[3]

The implacable chase of the authorities on the resisters as well as the gag order on the existence of the resistance show how concerned the regime was, that the symbol of political insubordination might become contagious.[4]

See also

- Brașov Rebellion

- Romanian Revolution

- Anti-Soviet partisans

- Vin americanii!

References

- Totok, William; Macovei, Elena-Irina (2016). Între mit și bagatelizare. Despre reconsiderarea critică a trecutului, Ion Gavrilă Ogoranu și rezistența armată anticomunistă din România. Polirom. pp. 103–104, 179–180. ISBN 978-973-46-6127-5.

- Consiliul National pentru Studierea Ahivelor Securităţii, Bande, bandiți si eroi. Grupurile de rezistență și Securitatea (1948-1968), Editura Enciclopedică, București, 2003

- Din istoria rezistenței anticomuniste in România, Adrian Stǎnescu, Curierul Românesc, Year XVI, number 5 (208), May 2004, pages 8–9.

- Deletant, Dennis (1999). "Chapter 10". Communist Terror in Romania. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 225–234.

- Stoica, Stan (coordinator). Dicționar de Istorie a României, p. 78. Bucharest: Editura Merona, 2007

- Claudia Dobre, Rezistenţa anticomunistă în România: memorie și istorie in Memoria, Revista gândirii arestate, Nr. 55 Archived 21 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Andrei Miroiu (2010): Wiping Out 'The Bandits': Romanian Counterinsurgency Strategies in the Early Communist Period. The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 23:4, p.676

- Kevin McDermott, Matthew Stibbe. Revolution and resistance in Eastern Europe: challenges to communist rule. p.84

- Gavrilă-Ogoranu Ion, Short History of Armed Anti-Communist Resistance in Romania in Ioniţoiu, C., Cartea de Aur a rezistenței româneşti împotriva comunismului. Vol. I-II, Bucureşti, Ed. Hrisovul, 1996

- Andrei Miroiu (2010): Wiping Out 'The Bandits': Romanian Counterinsurgency Strategies in the Early Communist Period. The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 23:4, p.684

- Miroiu, p. 684

- Consiliul Naţional pentru Studierea Arhivelor Securităţii, Mişcarea armată de rezistenţă anticomunistă din Romania. 1944-1962, Editura Kullusys, Bucureşti, 2003

- Dobre Florica (Edt.), Bande, bandiţi şi eroi. Grupurile de rezistenţă şi Securitatea (1948-1968), Ed. Enciclopedică, Bucureşti, 2003

- Ioniţoiu Cicerone, Rezistenţa anticomunistă din munţii României, 1946 - 1958., "Gîndirea Românească", 1993 also see online document

- Brișca, Adrian, The Anticommunist Armed Resistance in Romania, 1944-1962, AT, nr. 34-35, 1-2/2002, p. 75-101

- Bellu, Ștefan. Rezistența în munții Maramureșului, in: AS, 1995, 2, p.320-326

- Brișcă Adrian, Rezistenţa armată din Bucovina, vol. al II-lea: 1950–1952, Institutul National pentru Studiul Totalitarismului, Bucuresti, 2000

- Brișcă Adrian, Jurnalul unui partizan:Vasile Motrescu și rezistența armată din Bucovina, 2005

- Brișcă, Adrian; Ciuceanu, Radu. Rezistenţa armată din Bucovina. 1944-1950. Vol. I, Bucureşti, 1998

- Radu Ciuceanu, Octavian Roske, Cristian Troncotă, Începuturile mișcării de rezistență, doc. 2, pp. 138-147

- Breazu, Steliana. Grupul de rezistență anticomunistă al lui Cantemir Gligor din munții Zarandului și munții Codrului, pe valea Crișului Alb, in: AS, 1995, 2, pp. 334–337

- Radu Ciuceanu, Octavian Roske, Cristian Troncotă, Începuturile mișcării de rezistenţă, vol. 2, iunie – noiembrie 1946, București, Institutul național pentru studiul totalitarismului, 2001, doc. 1–10, pp. 30–40

- Cristian Troncotă, "Procesul mișcării naționale de rezistență", 1946, in Arhivele Totalitarismului, nr. 19–20, 2–3/1998, pp. 102–120

- Cristian Troncotă, Procesul mişcării naţionale de rezistenţă, p. 225

- Grupul de rezistenţă "maior Nicolae Dabija" in: Memoria, nr. 13, pp. 59–67

- Jurj-Costescu, Lucreția (1999), "Patru ani de rezistență cu arma în mână în Munții Apuseni", Memoria. Revista gândirii arestate, 26: 100–107, retrieved 30 May 2020

- Ivan Paula. Aspects du mouvement de résistance anti-communiste a Cluj et a Alba, 1947–1952. In: Trans. R, 1995, 4, nr. 4, p.116-121

- Berzescu Atanasie, Lacrimi și sânge. Rezistența anticomunistă armată din munții Banatului, Editura Marineasa, Timișoara, 1999

- Brişcă Adrian, Rezistenţa armată din Banat vol. 1, 1945-1949, Editura Institutul Național pentru Studiul Totalitarismului - 2004

- Matei, Tudor. Rezistența anticomunistă din Mehedinți In: AS, 1998, 6, p.250-255

- Sebeșan, Emil; Silveanu, Ileana. Rezistența din Banat. 1949 (La Résistance de Banat, 1949). In: A tot., 1998, 6, nr. 1, p.116-138

- Theodor Bărbulescu, Liviu Țăranu Rezistența anticomunistă – Cazul colonelului I. Uță in Memoria, Revista gândirii arestate nr. 44-45Archived 11 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Baicu, Petre, Salcă, Alexandru, Rezistența în munți și orașul Brașov (1944-1948) Brașov, Ed. Transilvania Express, 1997

- Radu Ciuceanu, Octavian Roske, Cristian Troncotă, Începuturile mișcării de rezistență, doc. 10, p. 153

- Timaru, Mihai. Lupta de rezistență anticomunistă în munții Vrancei. In: AS, 1995, 2, p.327-333

- Gavrilă Ogoranu Ion, Baki Lucia Brazii se frâng, dar nu se îndoiesc Vol.III, Editura Marineasa, Timișoara

- Căpăţână, Claudia; Ciolcă, Răzvan. Fişe pentru o istorie a rezistenţei anticomuniste. Grupul "Haiducii Muscelului" In: MI, 1998, 32, nr. 6, pp. 40–44

- Memoria, 1998, nr. 25, p. 138; Ioniţoiu, 1995, p. 158; I.N.S.T. nr. 16-17 /1997, p. 45)

- Cojoc Marian – Rezistenţa armată din Dobrogea, 1945–1960, Ed. Institutul Național pentru Studierea Totalitarismului, București, 2004

- Rădulescu, Zoe. Rezistența anticomunistă din munții Babadag, in: AS, 1995, 2, pp. 311–319

- Onișoru Gheorghe (coord.) – Totalitarism şi rezistenţă, teroare şi represiune în România comunistă, Studii C.N.S.A.S, București, 2001

- Addenda in Stéphane Courtois, Du passé faisons table rase! Histoire et mémoire du communisme en Europe, Éditions Robert Laffont, Paris, 2002

- Miroiu, p.682

- Deletant, Dennis (1999). Communist Terror in Romania. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 122–123.

External links

- William Totok, Elena-Irina Macovei: Între mit şi bagatelizare. Despre reconsiderarea critică a trecutului, Ion Gavrilă Ogoranu şi rezistenţa armată anticomunistă din România, Editura Polirom, Iași, 2016.

- (in French) Georges Diener, "Résistance Paysanne et Maquis en Roumanie de 1945 à 1965 - La résistance paysanne à la collectivisation", Genèses - Sciences sociales et histoireno, no. 43, 2001/2

- (in English) Toma Arnăuțoiu - The anti-communist partisans of Nucșoara - Biography, photos, documents about Toma Arnăuțoiu.