Montreal

Montreal (/ˌmʌntriˈɔːl/ (![]()

![]()

Montreal | |

|---|---|

| City of Montreal Ville de Montréal (French) | |

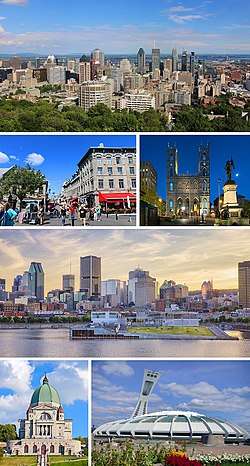

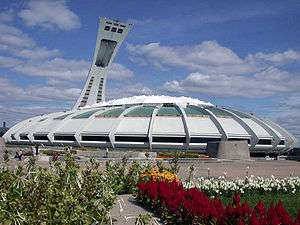

From top, left to right: Downtown Montreal skyline, Old Montreal, Notre-Dame Basilica, Old Port of Montreal, Saint Joseph's Oratory, Olympic Stadium | |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto(s): Concordia Salus ("well-being through harmony") | |

Location within urban agglomeration | |

Montreal Location within Quebec  Montreal Location within Canada  Montreal Location within North America | |

| Coordinates: 45°30′32″N 73°33′42″W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Quebec |

| Region | Montreal |

| UA | Urban agglomeration of Montreal |

| Founded | May 17, 1642 |

| Incorporated | 1832 |

| Constituted | January 1, 2002 |

| Boroughs | List

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Montreal City Council |

| • Mayor | Valérie Plante |

| • Federal riding | List

|

| • Prov. riding | List

|

| • MPs | List of MPs

|

| Area | |

| • City | 431.50 km2 (166.60 sq mi) |

| • Land | 365.13 km2 (140.98 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,293.99 km2 (499.61 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 4,604.26 km2 (1,777.71 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 233 m (764 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 6 m (20 ft) |

| Population (2016)[10] | |

| • City | 1,704,694 |

| • Density | 3,889/km2 (10,070/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,519,595 |

| • Urban density | 2,719/km2 (7,040/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 4,098,927 (2nd) |

| • Metro density | 890/km2 (2,300/sq mi) |

| • Pop 2011–2016 | |

| • Dwellings | 939,112 |

| Demonym(s) | Montrealer Montréalais(e)[13] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| Postal code(s) | H (except H7 for Laval) |

| Area code(s) | 514 and 438 and 263 |

| GDP | US$155.9 billion[14] |

| GDP per capita | US$38,867[14] |

| Website | montreal |

In 2016, the city had a population of 1,704,694,[10] with a population of 1,942,247 in the urban agglomeration, including all of the other municipalities on the Island of Montreal.[10] The broader metropolitan area had a population of 4,098,247.[12] French is the city's official language[19][20] and in 2016 was the main home language of 49.8% of the population, while English was spoken by 22.8% at home, and 18.3% spoke other languages (multi-language responses were excluded from these figures).[10] In the larger Montreal Census Metropolitan Area, 65.8% of the population spoke French at home, compared to 15.3% who spoke English.[12] Montreal is one of the most bilingual cities in Quebec and Canada, with over 59% of the population able to speak both English and French.[10] Montreal is the second-largest primarily French-speaking city in the developed world, after Paris.[21][22][23][24]

Historically the commercial capital of Canada, Montreal was surpassed in population and in economic strength by Toronto in the 1970s.[25] It remains an important centre of commerce, aerospace, transport, finance, pharmaceuticals, technology, design, education, art, culture, tourism, food, fashion, video game development, film, and world affairs. Montreal has the second-highest number of consulates in North America,[26] serves as the location of the headquarters of the International Civil Aviation Organization, and was named a UNESCO City of Design in 2006.[27][28] In 2017, Montreal was ranked the 12th most liveable city in the world by the Economist Intelligence Unit in its annual Global Liveability Ranking,[29] and the best city in the world to be a university student in the QS World University Rankings.[30]

Montreal has hosted multiple international conferences and events, including the 1967 International and Universal Exposition and the 1976 Summer Olympics.[31][32] It is the only Canadian city to have held the quadrennial Summer Olympics. In 2018, Montreal was ranked as an Alpha− world city.[33] As of 2016 the city hosts the Canadian Grand Prix of Formula One,[34] the Montreal International Jazz Festival[35] and the Just for Laughs festival.[36] It is also home to ice hockey team Montreal Canadiens, the franchise with the most Stanley Cup wins.

Etymology

In the Mohawk language, the island is called Tiohtià:ke Tsi. This name refers to the Lachine Rapids to the island's southwest or Ka-wé-no-te. It means "a place where nations and rivers unite and divide".

In the Ojibwe language the land is called Mooniyaang[37] which served as "the first stopping place" in Ojibwe migration story as related in the seven fires prophecy.

European settlers from La Flèche in the Loire valley first named their new town, founded in 1642, Ville Marie ("City of Mary"),[15] named for the Virgin Mary.[38] Its current name comes from Mount Royal,[16] the triple-peaked hill in the heart of the city. According to one theory, the name derives from mont Réal, (Mont Royal in modern French, although in 16th-century French the forms réal and royal were used interchangeably); Cartier's 1535 diary entry, naming the mountain, refers to le mont Royal.[39] One possibility, noted by the Government of Canada on its web site concerning Canadian place names, speculates that the name as it is currently written originated when an early map of 1556 used the Italian name of the mountain, Monte Real;[40] the Commission de toponymie du Québec has dismissed this idea as a misconception.[39]

History

Pre-European contact

Archaeological evidence in the region indicate that First Nations native people occupied the island of Montreal as early as 4,000 years ago.[41] By the year AD 1000, they had started to cultivate maize. Within a few hundred years, they had built fortified villages.[42] The Saint Lawrence Iroquoians, an ethnically and culturally distinct group from the Iroquois nations of the Haudenosaunee (then based in present-day New York), established the village of Hochelaga at the foot of Mount Royal two centuries before the French arrived. Archeologists have found evidence of their habitation there and at other locations in the valley since at least the 14th century.[43] The French explorer Jacques Cartier visited Hochelaga on October 2, 1535, and estimated the population of the native people at Hochelaga to be "over a thousand people".[43] Evidence of earlier occupation of the island, such as those uncovered in 1642 during the construction of Fort Ville-Marie, have effectively been removed.

Early European settlement (1600–1760)

In 1603, the French explorer Samuel de Champlain reported that the St Lawrence Iroquoians and their settlements had disappeared altogether from the St Lawrence valley. This is believed to be due to outmigration, epidemics of European diseases, or intertribal wars.[43][44] In 1611 Champlain established a fur trading post on the Island of Montreal, on a site initially named La Place Royale. At the confluence of Petite Riviere and St. Lawrence River, it is where present-day Pointe-à-Callière stands.[45] On his 1616 map, Samuel de Champlain named the island Lille de Villemenon, in honour of the sieur de Villemenon, a French dignitary who was seeking the viceroyship of New France.[46] In 1639 Jérôme Le Royer de La Dauversière obtained the Seigneurial title to the Island of Montreal in the name of the Notre Dame Society of Montreal to establish a Roman Catholic mission to evangelize natives.

Dauversiere hired Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve, then 30, to lead a group of colonists to build a mission on his new seigneury. The colonists left France in 1641 for Quebec, and arrived on the island the following year. On May 17, 1642, Ville-Marie was founded on the southern shore of Montreal island, with Maisonneuve as its first governor. The settlement included a chapel and a hospital, under the command of Jeanne Mance.[47] By 1643, Ville-Marie had already been attacked by Iroquois raids. In the spring of 1651, the Iroquois attacks became so frequent and so violent that Ville Marie thought its end had come. Maisonneuve made all the settlers take refuge in the fort. By 1652 the colony at Montreal had been so reduced that he was forced to return to France to raise 100 volunteers to go with him to the colony the following year. If the effort had failed, Montreal was to be abandoned and the survivors re-located downriver to Quebec City. Before these 100 arrived in the fall of 1653, the population of Montreal was barely 50 people.

By 1685 Ville Marie was home to some 600 colonists, most of them living in modest wooden houses. Ville Marie became a centre for the fur trade and a base for further exploration.[47] In 1689 the English-allied Iroquois attacked Lachine on the Island of Montreal, committing the worst massacre in the history of New France.[48] By the early 18th century, the Sulpician Order was established there. To encourage French settlement, they wanted the Mohawk to move away from the fur trading post at Ville Marie. They had a mission village, known as Kahnewake, south of the St Lawrence River. The fathers persuaded some Mohawk to make a new settlement at their former hunting grounds north of the Ottawa River. This became Kanesatake.[49] In 1745 several Mohawk families moved upriver to create another settlement, known as Akwesasne. All three are now Mohawk reserves in Canada. The Canadian territory was ruled as a French colony until 1760, when Montreal fell to a British offensive during the Seven Years' War. The colony then surrendered to Great Britain.[50]

Ville Marie was the name for the settlement that appeared in all official documents until 1705, when Montreal appeared for the first time, although people referred to the "Island of Montreal" long before then.[51]

Modern history (1761–present)

Montreal was incorporated as a city in 1832.[52] The opening of the Lachine Canal permitted ships to bypass the unnavigable Lachine Rapids,[53] while the construction of the Victoria Bridge established Montreal as a major railway hub. The leaders of Montreal's business community had started to build their homes in the Golden Square Mile (~2.6 km2) from about 1850. By 1860, it was the largest municipality in British North America and the undisputed economic and cultural centre of Canada.[54][55]

In the 19th century maintaining Montreal's drinking water became increasingly difficult with the rapid increase in population. A majority of the drinking water was still coming from the city's harbor, which was busy and heavily trafficked leading to the deterioration of the water within. In the mid 1840s the City of Montreal installed a water system that would pump water from the St. Lawrence and into cisterns. The cisterns would then be transported to the desired location. This was not the first water system of its type in Montreal as there had been one in private ownership since 1801. In the middle of the 19th century water distribution was carried out by "fontainiers". The fountainiers would open and close water valves outside of buildings, as directed, all over the city. As they lacked modern plumbing systems it was impossible to connect all buildings at once and it also acted as a conservation method. The population was not finished rising yet however, from 58,000 in 1852 it rose to 267,000 by 1901.[56][57][58]

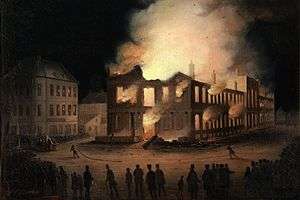

Montreal was the capital of the Province of Canada from 1844 to 1849, but lost its status when a Tory mob burnt down the Parliament building to protest the passage of the Rebellion Losses Bill.[59] Thereafter, the capital rotated between Quebec City and Toronto, until in 1857 Queen Victoria herself established Ottawa as the capital, for strategic reasons. The reasons were twofold; as it was located more in the interior of the Province of Canada, it was less susceptible to US attack. Perhaps more importantly, as it lay on the border between French and English Canada, the small town of Ottawa was seen as a compromise between Montreal, Toronto, Kingston and Quebec City, who were all vying to become the young nation's official capital. Ottawa retained the status as capital of Canada when the Province of Canada joined with Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to form the Dominion of Canada in 1867.

An internment camp was set up at Immigration Hall in Montreal from August 1914 to November 1918.[60]

After World War I, the prohibition movement in the United States led to Montreal becoming a destination for Americans looking for alcohol.[61] Unemployment remained high in the city, and was exacerbated by the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression.[62]

During World War II, Mayor Camillien Houde protested against conscription and urged Montrealers to disobey the federal government's registry of all men and women.[63] The Government, part of the Allied forces, was furious over Houde's stand and held him at a prison camp until 1944.[64] That year the government decided to institute conscription to expand the armed forces and fight the Nazis. (See Conscription Crisis of 1944.)[63]

Montreal was the official residence of the Luxembourg royal family in exile during World War II.[65]

By 1951 Montreal's population had surpassed one million.[66] However, Toronto's growth had begun challenging Montreal's status as the economic capital of Canada. Indeed, the volume of stocks traded at the Toronto Stock Exchange had already surpassed that traded at the Montreal Stock Exchange in the 1940s.[67] The Saint Lawrence Seaway opened in 1959, allowing vessels to bypass Montreal. In time this development led to the end of the city's economic dominance as businesses moved to other areas.[68] During the 1960s there was continued growth, Canada's tallest skyscrapers, new expressways and the subway system known as the Montreal Metro were finished during this time, and Montreal held the World's Fair of 1967, better known as Expo67

The 1970s ushered in a period of wide-ranging social and political changes, stemming largely from the concerns of the French speaking majority about the conservation of their culture and language, given the traditional predominance of the English Canadian minority in the business arena.[69] The October Crisis, and the 1976 election of the Parti Québécois, supporting sovereign status for Quebec, resulted in the departure of many businesses and people from the city.[70] In 1976, Montreal was the host of the Olympics, while it brought the city International prestige, and attention, the Olympic Stadium built for the event costed the city massive debt.[71] During the 1980s and early 1990s, Montreal experienced a slower rate of economic growth than many other major Canadian cities. Montreal was the site of the 1989 École Polytechnique massacre, Canada's worst mass shooting, where 25-year-old Marc Lépine shot and killed 14 people, all of them women, and wounding 14 other people before shooting himself at École Polytechnique.

Montreal was merged with the 27 surrounding municipalities on the Island of Montreal on January 1, 2002, creating a unified city covering the entire island. There was great resistance from the suburbs to the merger, with the perception being that it was forced on the mostly English suburbs by the Parti Québécois. As expected, this move proved unpopular and several mergers were later rescinded. Several former municipalities, totalling 13% of the population of the island, voted to leave the unified city in separate referendums in June 2004. The demerger took place on January 1, 2006, leaving 15 municipalities on the island, including Montreal. De-merged municipalities remain affiliated with the city through an agglomeration council that collects taxes from them to pay for numerous shared services.[72] The 2002 mergers were not the first in the city's history. Montreal annexed 27 other cities, towns, and villages beginning with Hochelaga in 1883 with the last prior to 2002 being Pointe-aux-Trembles in 1982.

The 21st century has brought with it a revival of the city's economic and cultural landscape. The construction of new residential skyscrapers, two super-hospitals (the Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal and McGill University Health Centre), the creation of the Quartier des Spectacles, reconstruction of the Turcot Interchange, reconfiguration of the Decarie and Dorval interchanges, construction of the new Réseau électrique métropolitain, gentrification of Griffintown, subway line extensions and the purchase of new subway cars, the complete revitalization and expansion of Trudeau International Airport, the completion of Quebec Autoroute 30, the reconstruction of the Champlain Bridge, and the construction of a new toll bridge to Laval are helping Montreal continue to grow.

Geography

Montreal is in the southwest of the province of Quebec. The city covers most of the Island of Montreal at the confluence of the Saint Lawrence and Ottawa Rivers. The port of Montreal lies at one end of the Saint Lawrence Seaway, the river gateway that stretches from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic.[73] Montreal is defined by its location between the Saint Lawrence river to its south and the Rivière des Prairies to its north. The city is named after the most prominent geographical feature on the island, a three-head hill called Mount Royal, topped at 232 m (761 ft) above sea level.[74]

Montreal is at the centre of the Montreal Metropolitan Community, and is bordered by the city of Laval to the north; Longueuil, Saint-Lambert, Brossard, and other municipalities to the south; Repentigny to the east and the West Island municipalities to the west. The anglophone enclaves of Westmount, Montreal West, Hampstead, Côte Saint-Luc, the Town of Mount Royal and the francophone enclave Montreal East are all surrounded by Montreal.[75]

Climate

Montreal is classified as a warm-summer humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification: Dfb) in the Montréal-Trudeau airport and a hot-summer humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification: Dfa) at McGill University.[76][77] Summers are warm to hot and humid with a daily maximum average of 26 to 27 °C (79 to 81 °F) in July; temperatures in excess of 30 °C (86 °F) are common. Conversely, cold fronts can bring crisp, drier and windy weather in the early and later parts of summer.

Winter brings cold, snowy, windy, and, at times, icy weather, with a daily average ranging from −10.5 to −9 °C (13.1 to 15.8 °F) in January. However, some winter days rise above freezing, allowing for rain on an average of 4 days in January and February each. Usually, snow covering some or all bare ground lasts on average from the first or second week of December until the last week of March.[78] While the air temperature does not fall below −30 °C (−22 °F) every year,[79] the wind chill often makes the temperature feel this low to exposed skin.

Spring and fall are pleasantly mild but prone to drastic temperature changes; spring even more so than fall.[80] Late season heat waves as well as "Indian summers" are possible. Early and late season snow storms can occur in November and March, and more rarely in April. Montreal is generally snow free from late April to late October. However, snow can fall in early to mid-October as well as early to mid-May on rare occasions.

The lowest temperature in Environment Canada's books was −37.8 °C (−36 °F) on January 15, 1957, and the highest temperature was 37.6 °C (99.7 °F) on August 1, 1975, both at Dorval International Airport.[81]

Before modern weather record keeping (which dates back to 1871 for McGill),[82] a minimum temperature almost 5 degrees lower was recorded at 7 a.m. on January 10, 1859, where it registered at −42 °C (−44 °F).[83]

Annual precipitation is around 1,000 mm (39 in), including an average of about 210 cm (83 in) of snowfall, which occurs from November through March. Thunderstorms are common in the period beginning in late spring through summer to early fall; additionally, tropical storms or their remnants can cause heavy rains and gales. Montreal averages 2,050 hours of sunshine annually, with summer being the sunniest season, though slightly wetter than the others in terms of total precipitation—mostly from thunderstorms.[84]

| Climate data for Montreal (Montréal–Trudeau International Airport), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1941–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 13.5 | 14.7 | 28.0 | 33.8 | 41.0 | 45.0 | 45.8 | 46.8 | 42.8 | 33.5 | 24.6 | 18.1 | 46.8 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.9 (57.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

25.8 (78.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

36.6 (97.9) |

35.0 (95.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

37.6 (99.7) |

33.5 (92.3) |

28.3 (82.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

37.6 (99.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −5.3 (22.5) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.3 (79.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

20.6 (69.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −9.7 (14.5) |

−7.7 (18.1) |

−2 (28) |

6.4 (43.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

8.5 (47.3) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

6.8 (44.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −14 (7) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

1.2 (34.2) |

7.9 (46.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

2.0 (35.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −37.8 (−36.0) |

−33.9 (−29.0) |

−29.4 (−20.9) |

−15 (5) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−19.4 (−2.9) |

−32.4 (−26.3) |

−37.8 (−36.0) |

| Record low wind chill | −49.1 | −46 | −42.9 | −26.3 | −9.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −4.8 | −10.9 | −30.7 | −46 | −49.1 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 77.2 (3.04) |

62.7 (2.47) |

69.1 (2.72) |

82.2 (3.24) |

81.2 (3.20) |

87.0 (3.43) |

89.3 (3.52) |

94.1 (3.70) |

83.1 (3.27) |

91.3 (3.59) |

96.4 (3.80) |

86.8 (3.42) |

1,000.3 (39.38) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 27.3 (1.07) |

20.9 (0.82) |

29.7 (1.17) |

67.7 (2.67) |

81.2 (3.20) |

87.0 (3.43) |

89.3 (3.52) |

94.1 (3.70) |

83.1 (3.27) |

89.1 (3.51) |

76.7 (3.02) |

38.8 (1.53) |

784.9 (30.90) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 49.5 (19.5) |

41.2 (16.2) |

36.2 (14.3) |

12.9 (5.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.8 (0.7) |

19.0 (7.5) |

48.9 (19.3) |

209.5 (82.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 16.7 | 13.7 | 13.6 | 12.9 | 13.6 | 13.3 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 11.1 | 13.3 | 14.8 | 16.3 | 163.3 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 4.2 | 4.0 | 6.9 | 11.6 | 13.6 | 13.3 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 11.1 | 13.0 | 11.7 | 5.9 | 119.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 15.3 | 12.1 | 9.1 | 3.2 | 0.07 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.72 | 5.4 | 13.0 | 58.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 1500) | 68.1 | 63.4 | 58.3 | 51.9 | 51.4 | 55.3 | 56.1 | 56.8 | 59.7 | 62.0 | 68.0 | 71.4 | 60.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 101.2 | 127.8 | 164.3 | 178.3 | 228.9 | 240.3 | 271.5 | 246.3 | 182.2 | 143.5 | 83.6 | 83.6 | 2,051.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 35.7 | 43.7 | 44.6 | 44.0 | 49.6 | 51.3 | 57.3 | 56.3 | 48.3 | 42.2 | 29.2 | 30.7 | 44.4 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source: Environment Canada[85][86] and Weather Atlas[87] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for McGill University (McTavish), 1971–2000 normals, extremes 1871–present[note 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.8 (55.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

30.1 (86.2) |

34.6 (94.3) |

34.5 (94.1) |

36.6 (97.9) |

35.6 (96.1) |

33.5 (92.3) |

28.9 (84.0) |

22.2 (72.0) |

17.0 (62.6) |

36.6 (97.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −5.4 (22.3) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

2.4 (36.3) |

11.0 (51.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

19.4 (66.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

5.1 (41.2) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −8.9 (16.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

7.0 (44.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

22.3 (72.1) |

20.8 (69.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

7.4 (45.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −12.4 (9.7) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

2.9 (37.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −33.5 (−28.3) |

−33.3 (−27.9) |

−28.9 (−20.0) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−5 (23) |

1.1 (34.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−33.9 (−29.0) |

−33.9 (−29.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 73.6 (2.90) |

70.9 (2.79) |

80.2 (3.16) |

76.9 (3.03) |

86.5 (3.41) |

87.5 (3.44) |

106.2 (4.18) |

100.6 (3.96) |

100.8 (3.97) |

84.3 (3.32) |

93.6 (3.69) |

101.5 (4.00) |

1,062.5 (41.83) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 28.4 (1.12) |

22.7 (0.89) |

42.2 (1.66) |

65.2 (2.57) |

86.5 (3.41) |

87.5 (3.44) |

106.2 (4.18) |

100.6 (3.96) |

100.8 (3.97) |

82.1 (3.23) |

68.9 (2.71) |

44.4 (1.75) |

834.9 (32.87) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 45.9 (18.1) |

46.6 (18.3) |

36.8 (14.5) |

11.8 (4.6) |

0.4 (0.2) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

2.2 (0.9) |

24.9 (9.8) |

57.8 (22.8) |

226.2 (89.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 15.8 | 12.8 | 13.6 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 13.8 | 12.3 | 13.4 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 15.0 | 16.2 | 163.9 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 4.3 | 4.0 | 7.4 | 10.9 | 12.8 | 13.8 | 12.3 | 13.4 | 12.7 | 12.7 | 11.5 | 6.5 | 122.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 13.6 | 11.1 | 8.3 | 3.0 | 0.14 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.62 | 5.3 | 12.0 | 53.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 99.2 | 119.5 | 158.8 | 181.7 | 229.8 | 250.1 | 271.6 | 230.7 | 174.1 | 138.6 | 80.4 | 80.7 | 2,015.2 |

| Source: Environment Canada,[88][89][90][91][92][93][94] record maximum[95][96] | |||||||||||||

Architecture

.jpg)

For over a century and a half, Montreal was the industrial and financial centre of Canada.[97] This legacy has left a variety of buildings including factories, elevators, warehouses, mills, and refineries, that today provide an invaluable insight into the city's history, especially in the downtown area and the Old Port area. There are 50 National Historic Sites of Canada, more than any other city.[98]

Some of the city's earliest still-standing buildings date back to the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Although most are clustered around the Old Montreal area, such as the Sulpician Seminary adjacent to Notre Dame Basilica that dates back to 1687, and Château Ramezay, which was built in 1705, examples of early colonial architecture are dotted throughout the city. Situated in Lachine, the Le Ber-Le Moyne House is the oldest complete building in the city, built between 1669–1671. In Point St. Charles visitors can see the Maison Saint-Gabriel, which can trace its history back to 1698.[99] There are many historic buildings in Old Montreal in their original form: Notre Dame of Montreal Basilica, Bonsecours Market, and the 19th‑century headquarters of all major Canadian banks on St. James Street (French: Rue Saint Jacques). Montreal's earliest buildings are characterized by their uniquely French influence and grey stone construction.

Saint Joseph's Oratory, completed in 1967, Ernest Cormier's Art Deco Université de Montréal main building, the landmark Place Ville Marie office tower, the controversial Olympic Stadium and surrounding structures, are but a few notable examples of the city's 20th-century architecture. Pavilions designed for the 1967 International and Universal Exposition, popularly known as Expo 67, featured a wide range of architectural designs. Though most pavilions were temporary structures, several have become landmarks, including Buckminster Fuller's geodesic dome U.S. Pavilion, now the Montreal Biosphere, and Moshe Safdie's striking Habitat 67 apartment complex.

The Montreal Metro has public artwork by some of the biggest names in Quebec culture.

In 2006 Montreal was named a UNESCO City of Design, only one of three design capitals of the world (the others being Berlin and Buenos Aires).[27] This distinguished title recognizes Montreal's design community. Since 2005 the city has been home for the International Council of Graphic Design Associations (Icograda);[100] the International Design Alliance (IDA).[101]

The Underground City (officially RESO) is an important tourist attraction. It is the set of interconnected shopping complexes (both above and below ground). This impressive network connects pedestrian thoroughfares to universities, as well as hotels, restaurants, bistros, subway stations and more, in and around downtown with 32 km (20 mi) of tunnels over 12 km2 (4.6 sq mi) of the most densely populated part of Montreal.

Neighbourhoods

The city is composed of 19 large boroughs, subdivided into neighbourhoods.[102] The boroughs are: Côte-des-Neiges–Notre-Dame-de-Grace, The Plateau Mount Royal, Outremont and Ville Marie in the centre; Mercier–Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, Rosemont–La Petite-Patrie and Villeray–Saint-Michel–Parc-Extension in the east; Anjou, Montréal-Nord, Rivière-des-Prairies–Pointe-aux-Trembles and Saint-Leonard in the northeast; Ahuntsic-Cartierville, L'Île-Bizard–Sainte-Geneviève, Pierrefonds-Roxboro and Saint-Laurent in the northwest; and Lachine, LaSalle, The South West and Verdun in the south.

Many of these boroughs were independent cities that were forced to be merged with Montreal in January 2002 following the 2002 Municipal Reorganization of Montreal.

The borough with the most neighbourhoods is Ville Marie, which includes downtown, the historical district of Old Montreal, Chinatown, the Gay Village, the Latin Quarter, the gentrified Quartier international and Cité Multimédia as well as the Quartier des Spectacles which is under development. Other neighbourhoods of interest in the borough include the affluent Golden Square Mile neighbourhood at the foot of Mount Royal and the Shaughnessy Village/Concordia U area home to thousands of students at Concordia University. The borough also comprises most of Mount Royal Park, Saint Helen's Island, and Notre-Dame Island.

The Plateau Mount Royal borough was a working class francophone area. The largest neighbourhood is the Plateau (not to be confused with the whole borough), which is undergoing considerable gentrification,[103] and a 2001 study deemed it as Canada's most creative neighbourhood because artists comprise 8% of its labour force.[104] The neighbourhood of Mile End in the northwestern part of the borough has been a very multicultural area of the city, and features two of Montreal's well-known bagel establishments, St-Viateur Bagel and Fairmount Bagel. The McGill Ghetto is in the extreme southwestern portion of the borough, its name being derived from the fact that it is home to thousands of McGill University students and faculty members.

The South West borough was home to much of the city's industry during the late 19th and early-to-mid 20th century. The borough included Goose Village and is home to the traditionally working-class Irish neighbourhoods of Griffintown and Point Saint Charles as well as the low-income neighbourhoods of Saint Henri and Little Burgundy.

Other notable neighbourhoods include the multicultural areas of Notre-Dame-de-Grâce and Côte-des-Neiges in the Côte-des-Neiges–Notre-Dame-de-Grace borough, and Little Italy in the borough of Rosemont–La Petite-Patrie and Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, home of the Olympic Stadium in the borough of Mercier–Hochelaga-Maisonneuve.

Old Montreal

Old Montreal is a historic area southeast of downtown containing many attractions such as the Old Port of Montreal, Place Jacques-Cartier, Montreal City Hall, the Bonsecours Market, Place d'Armes, Pointe-à-Callière Museum, the Notre-Dame de Montréal Basilica, and the Montreal Science Centre.

Architecture and cobbled streets in Old Montreal have been maintained or restored and are frequented by horse-drawn buggies carrying tourists. Old Montreal is accessible from the downtown core via the underground city and is served by several STM bus routes and Metro stations, ferries to the South Shore and a network of bicycle paths.

The riverside area adjacent to Old Montreal is known as the Old Port. The Old Port was the site of the Port of Montreal, but its shipping operations have been moved to a larger site downstream, leaving the former location as a recreational and historical area maintained by Parks Canada. The new Port of Montreal is Canada's largest container port and the largest inland port on Earth.[105]

Mount Royal

The mountain is the site of Mount Royal Park, one of Montreal's largest greenspaces. The park, most of which is wooded, was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, who also designed New York's Central Park, and was inaugurated in 1876.[106]

The park contains two belvederes, the more prominent of which is the Kondiaronk Belvedere, a semicircular plaza with a chalet overlooking Downtown Montreal. Other features of the park are Beaver Lake, a small man-made lake, a short ski slope, a sculpture garden, Smith House, an interpretive centre, and a well-known monument to Sir George-Étienne Cartier. The park hosts athletic, tourist and cultural activities.

The mountain is home to two major cemeteries, Notre-Dame-des-Neiges (founded in 1854) and Mount Royal (1852). Mount Royal Cemetery is a 165 acres (67 ha) terraced cemetery on the north slope of Mount Royal in the borough of Outremont. Notre Dame des Neiges Cemetery is much larger, predominantly French-Canadian and officially Catholic.[107] More than 900,000 people are buried there.[108]

Mount Royal Cemetery contains more than 162,000 graves and is the final resting place for a number of notable Canadians. It includes a veterans section with several soldiers who were awarded the British Empire's highest military honour, the Victoria Cross. In 1901 the Mount Royal Cemetery Company established the first crematorium in Canada.[109]

The first cross on the mountain was placed there in 1643 by Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve, the founder of the city, in fulfilment of a vow he made to the Virgin Mary when praying to her to stop a disastrous flood.[106] Today, the mountain is crowned by a 31.4 m-high (103 ft) illuminated cross, installed in 1924 by the John the Baptist Society and now owned by the city.[106] It was converted to fibre optic light in 1992.[106] The new system can turn the lights red, blue, or purple, the last of which is used as a sign of mourning between the death of the Pope and the election of the next.[110]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1871 | 141,276 | — |

| 1881 | 189,168 | +33.9% |

| 1891 | 271,352 | +43.4% |

| 1901 | 347,817 | +28.2% |

| 1911 | 533,341 | +53.3% |

| 1921 | 693,225 | +30.0% |

| 1931 | 959,198 | +38.4% |

| 1941 | 1,064,653 | +11.0% |

| 1951 | 1,247,647 | +17.2% |

| 1956 | 1,402,704 | +12.4% |

| 1961 | 1,607,601 | +14.6% |

| 1966 | 1,750,969 | +8.9% |

| 1971 | 1,765,553 | +0.8% |

| 1976 | 1,664,527 | −5.7% |

| 1981 | 1,554,761 | −6.6% |

| 1986 | 1,541,251 | −0.9% |

| 1991 | 1,553,356 | +0.8% |

| 1996 | 1,550,369 | −0.2% |

| 2001 | 1,583,590 | +2.1% |

| 2006 | 1,620,639 | +2.3% |

| 2011 | 1,649,519 | +1.8% |

| 2016 | 1,704,694 | +3.3% |

| Based on current city limits Source: [111][112][113] | ||

According to Statistics Canada, at the 2016 Canadian census the city had 1,704,694 inhabitants.[114] A total of 4,098,927 lived in the Montreal Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) at the same 2016 census, up from 3,934,078 at the 2011 census (within 2011 CMA boundaries), which is a population growth of 4.19% from 2011 to 2016.[115] In 2015, the Greater Montreal population was estimated at 4,060,700.[116][117] According to StatsCan, by 2030, the Greater Montreal Area is expected to number 5,275,000 with 1,722,000 being visible minorities.[118] In the 2016 census, children under 14 years of age (691,345) constituted 16.9%, while inhabitants over 65 years of age (671,690) numbered 16.4% of the total population of the CMA.[115]

.jpg)

People of European ethnicities formed the largest cluster of ethnic groups. The largest reported European ethnicities in the 2006 census were French 23%, Italians 10%, Irish 5%, English 4%, Scottish 3%, and Spanish 2%.[119] Some 26% of the population of Montreal and 16.5% that of Greater Montreal, are members of a visible minority (non-white) group,[120] up from 5.2% in 1981.[121]

Visible minorities comprised 34.2% of the population in the 2016 census. The five most numerous visible minorities are Black people (10.3%), Arabs, mainly Lebanese (7.3%), Latin Americans (4.1%), South Asians (3.3%), and Chinese (3.3%).[122] Visible minorities are defined by the Canadian Employment Equity Act as "persons, other than Aboriginals, who are non-white in colour".[123]

In terms of mother language (first language learned), the 2006 census reported that in the Greater Montreal Area, 66.5% spoke French as a first language, followed by English at 13.2%, while 0.8% spoke both as a first language.[124] The remaining 22.5% of Montreal-area residents are allophones, speaking languages including Italian (3.5%), Arabic (3.1%), Spanish (2.6%), Creole (1.3%), Chinese (1.2%), Greek (1.2%), Portuguese (0.8%), Romanian (0.7%), Vietnamese (0.7%), and Russian (0.7%).[124] In terms of additional languages spoken, a unique feature of Montreal among Canadian cities, noted by Statistics Canada, is the working knowledge of both French and English possessed by most of its residents.[125]

| Canada Census Mother Tongue – Montreal, Quebec[126] | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Total | French |

English |

French and English |

Other | |||||||||||||

| Year | Responses | Count | Trend | Pop % | Count | Trend | Pop % | Count | Trend | Pop % | Count | Trend | Pop % | |||||

2016 |

1,680,910 |

833,280 | 49.57% | 208,140 | 12.38% | 20,705 | 1.27% | 559,035 | 34.34% | |||||||||

2011 |

1,627,945 |

818,970 | 50.3% | 206,210 | 12.67% | 17,430 | 1.07% | 536,560 | 32.30% | |||||||||

2006 |

1,593,725 |

834,520 | 52.36% | 200,000 | 12.5% | 12,055 | 0.75% | 547,150 | 34.33% | |||||||||

2001 |

1,608,024 |

873,564 | 54.32% | 206,025 | 12.81% | 16,807 | 1.04% | 484,165 | 30.1% | |||||||||

1996 |

1,569,437 |

855,780 | n/a | 54.53% | 215,100 | n/a | 13.7% | 14,740 | n/a | 0.94% | 425,725 | n/a | 27.12% | |||||

The Greater Montreal Area is predominantly Roman Catholic; however, weekly attendance in Quebec is among the lowest in Canada.[128] Historically Montreal has been a centre of Catholicism in North America with its numerous seminaries and churches, including the Notre-Dame Basilica, the Cathédrale Marie-Reine-du-Monde, and Saint Joseph's Oratory. Some 65.8% of the total population is Christian,[127] largely Roman Catholic (52.8%), primarily because of descendants of original French settlers, and others of Italian and Irish origins. Protestants which include Anglican Church in Canada, United Church of Canada, Lutheran, owing to British and German immigration, and other denominations number 5.90%, with a further 3.7% consisting mostly of Orthodox Christians, fuelled by a large Greek population. There is also a number of Russian and Ukrainian Orthodox parishes. Islam is the largest non-Christian religious group, with 154,540 members,[129] the second-largest concentration of Muslims in Canada at 9.6%. The Jewish community in Montreal has a population of 90,780.[130] In cities such as Côte Saint-Luc and Hampstead, Jewish people constitute the majority, or a substantial part of the population. As recently as 1971 the Jewish community in Greater Montreal was as high as 109,480.[131] Political and economic uncertainties led many to leave Montreal and the province of Quebec.[132]

Economy

Montreal has the second-largest economy of Canadian cities based on GDP[133] and the largest in Quebec. In 2014, Metropolitan Montreal was responsible for C$118.7 billion of Quebec's C$340.7 billion GDP.[134] The city is today an important centre of commerce, finance, industry, technology, culture, world affairs and is the headquarters of the Montreal Exchange. In recent decades, the city was widely seen as weaker than that of Toronto and other major Canadian cities, but it has recently experienced a revival.[135]

Industries include aerospace, electronic goods, pharmaceuticals, printed goods, software engineering, telecommunications, textile and apparel manufacturing, tobacco, petrochemicals, and transportation. The service sector is also strong and includes civil, mechanical and process engineering, finance, higher education, and research and development. In 2002, Montreal was the fourth-largest centre in North America in terms of aerospace jobs.[136] The Port of Montreal is one of the largest inland ports in the world handling 26 million tonnes of cargo annually.[137] As one of the most important ports in Canada, it remains a transshipment point for grain, sugar, petroleum products, machinery, and consumer goods. For this reason, Montreal is the railway hub of Canada and has always been an extremely important rail city; it is home to the headquarters of the Canadian National Railway,[138] and was home to the headquarters of the Canadian Pacific Railway until 1995.[139]

The headquarters of the Canadian Space Agency is in Longueuil, southeast of Montreal.[140] Montreal also hosts the headquarters of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO, a United Nations body);[141] the World Anti-Doping Agency (an Olympic body);[142] the Airports Council International (the association of the world's airports – ACI World);[143] the International Air Transport Association (IATA),[144] IATA Operational Safety Audit and the International Gay and Lesbian Chamber of Commerce (IGLCC),[145] as well as some other international organizations in various fields.

Montreal is a centre of film and television production. The headquarters of Alliance Films and five studios of the Academy Award-winning documentary producer National Film Board of Canada are in the city, as well as the head offices of Telefilm Canada, the national feature-length film and television funding agency and Télévision de Radio-Canada. Given its eclectic architecture and broad availability of film services and crew members, Montreal is a popular filming location for feature-length films, and sometimes stands in for European locations.[146][147] The city is also home to many recognized cultural, film and music festivals (Just For Laughs, Just For Laughs Gags, Montreal International Jazz Festival, Montreal World Film Festival, and others), which contribute significantly to its economy. It is also home to one of the world's largest cultural enterprises, the Cirque du Soleil.[148]

Montreal is also a global hub for artificial intelligence research with many companies involved in this sector, such as Facebook AI Research (FAIR), Microsoft Research, Google Brain, DeepMind, Samsung Research and Thales Group (cortAIx).[149][150]

The video game industry has been booming in Montreal since 1997, coinciding with the opening of Ubisoft Montreal.[151] Recently, the city has attracted world leading game developers and publishers studios such as EA, Eidos Interactive, BioWare, Artificial Mind and Movement, Strategy First, THQ, Gameloft mainly because of the quality of local specialized labor, and tax credits offered to the corporations. Recently, Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment, a division of Warner Bros., announced that it would open a video game studio.[152] Relatively new to the video game industry, it will be Warner Bros. first studio opened, not purchased, and will develop games for such Warner Bros. franchises as Batman and other games from their DC Comics portfolio. The studio will create 300 jobs.

Montreal plays an important role in the finance industry. The sector employs approximately 100,000 people in the Greater Montreal Area.[153] As of March 2018, Montreal is ranked in the 12th position in the Global Financial Centres Index, a ranking of the competitiveness of financial centres around the world.[154] The city is home to the Montreal Exchange, the oldest stock exchange in Canada and the only financial derivatives exchange in the country.[155] The corporate headquarters of the Bank of Montreal and Royal Bank of Canada, two of the biggest banks in Canada, were in Montreal. While both banks moved their headquarters to Toronto, Ontario, their legal corporate offices remain in Montreal. The city is home to head offices of two smaller banks, National Bank of Canada and Laurentian Bank of Canada. The Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, an institutional investor managing assets totalling $248 billion CAD, has its main business office in Montreal.[156] Many foreign subsidiaries operating in the financial sector also have offices in Montreal, including HSBC, Aon, Société Générale, BNP Paribas and AXA.[155][157]

Several companies are headquartered in Greater Montreal Area including Rio Tinto Alcan,[158] Bombardier Inc.,[159] Canadian National Railway,[160] CGI Group,[161] Air Canada,[162] Air Transat,[163] CAE,[164] Saputo,[165] Cirque du Soleil, Stingray Group, Quebecor,[166] Ultramar, Kruger Inc., Jean Coutu Group,[167] Uniprix,[168] Proxim,[169] Domtar, Le Château,[170] Power Corporation, Cellcom Communications,[171] Bell Canada.[172] Standard Life,[173] Hydro-Québec, AbitibiBowater, Pratt and Whitney Canada, Molson,[174] Tembec, Canada Steamship Lines, Fednav, Alimentation Couche-Tard, SNC-Lavalin,[175] MEGA Brands,[176] Aeroplan,[177] Agropur,[178] Metro Inc.,[179] Laurentian Bank of Canada,[180] National Bank of Canada,[181] Transat A.T.,[182] Via Rail,[183] GardaWorld, Novacam Technologies, SOLABS,[184] Dollarama,[185] Rona[186] and the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec.

The Montreal Oil Refining Centre is the largest refining centre in Canada, with companies like Petro-Canada, Ultramar, Gulf Oil, Petromont, Ashland Canada, Parachem Petrochemical, Coastal Petrochemical, Interquisa (Cepsa) Petrochemical, Nova Chemicals, and more. Shell decided to close the refining centre in 2010, throwing hundreds out of work and causing an increased dependence on foreign refineries for eastern Canada.

Culture

Montreal was referred to as "Canada's Cultural Capital" by Monocle magazine.[28] The city is Canada's centre for French-language television productions, radio, theatre, film, multimedia, and print publishing. Montreal's many cultural communities have given it a distinct local culture.

As a North American city, Montreal shares many cultural characteristics with the rest of the continent. It has a tradition of producing both jazz and rock music. The city has also produced much talent in the fields of visual arts, theatre, music, and dance. Yet, being at the confluence of the French and the English traditions, Montreal has developed a unique and distinguished cultural face. Another distinctive characteristic of cultural life is the vibrancy of its downtown, particularly during summer, prompted by cultural and social events, including its more than 100 annual festivals, the largest being the Montreal International Jazz Festival which is the largest jazz festival in the world. Other popular events include the Just for Laughs (largest comedy festival in the world), Montreal World Film Festival, Les FrancoFolies de Montréal, Nuits d'Afrique, Pop Montreal, Divers/Cité, Fierté Montréal and the Montreal Fireworks Festival, and many smaller festivals.

A cultural heart of classical art and the venue for many summer festivals, the Place des Arts is a complex of different concert and theatre halls surrounding a large square in the eastern portion of downtown. Place des Arts has the headquarters of one of the world's foremost orchestras, the Montreal Symphony Orchestra. The Orchestre Métropolitain du Grand Montréal and the chamber orchestra I Musici de Montréal are two other well-regarded Montreal orchestras. Also performing at Place des Arts are the Opéra de Montréal and the city's chief ballet company Les Grands Ballets Canadiens. Internationally recognized avant-garde dance troupes such as Compagnie Marie Chouinard, La La La Human Steps, O Vertigo, and the Fondation Jean-Pierre Perreault have toured the world and worked with international popular artists on videos and concerts. The unique choreography of these troupes has paved the way for the success of the world-renowned Cirque du Soleil.

Nicknamed la ville aux cent clochers (the city of a hundred steeples), Montreal is renowned for its churches. As Mark Twain noted, "This is the first time I was ever in a city where you couldn't throw a brick without breaking a church window."[187] The city has four Roman Catholic basilicas: Mary, Queen of the World Cathedral, the aforementioned Notre-Dame Basilica, St Patrick's Basilica, and Saint Joseph's Oratory. The Oratory is the largest church in Canada, with the second largest copper dome in the world, after Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome.[188]

Sports

The most popular sport is ice hockey. The professional hockey team, the Montreal Canadiens, is one of the Original Six teams of the National Hockey League (NHL), and has won an NHL-record 24 Stanley Cup championships. The Canadiens' most recent Stanley Cup victory came in 1993. They have major rivalries with the Toronto Maple Leafs and Boston Bruins, both of which are also Original Six hockey teams, and with the Ottawa Senators, the closest team geographically. The Canadiens have played at the Bell Centre since 1996. Prior to that they played at the Montreal Forum.

The Montreal Alouettes of the Canadian Football League (CFL) play at Molson Stadium on the campus of McGill University for their regular-season games. Late season and playoff games are played at the much larger, enclosed Olympic Stadium, which also played host to the 2008 Grey Cup. The Alouettes have won the Grey Cup seven times, most recently in 2010. The Alouettes has had two periods on hiatus. During the second one, the Montreal Machine played in the World League of American Football in 1991 and 1992. The McGill Redmen, Concordia Stingers, and Université de Montréal Carabins play in the CIS university football league.

Montreal has a storied baseball history. The city was the home of the minor-league Montreal Royals of the International League until 1960. In 1946 Jackie Robinson broke the baseball colour barrier with the Royals in an emotionally difficult year; Robinson was forever grateful for the local fans' fervent support.[189] Major League Baseball came to town in the form of the Montreal Expos in 1969. They played their games at Jarry Park until moving into Olympic Stadium in 1977. After 36 years in Montreal, the team relocated to Washington, D.C. in 2005 and re-branded themselves as the Washington Nationals.[190] Discussions about MLB returning to Montreal remain active.[191]

The Montreal Impact are the city's professional soccer team. They play at a soccer-specific stadium called Saputo Stadium. They joined North America's biggest soccer league, Major League Soccer in 2012. The Montreal games of the 2007 FIFA U-20 World Cup[192] and 2014 FIFA U-20 Women's World Cup[193] were held at Olympic Stadium, and the venue hosted Montreal games in the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup.[194]

Montreal is the site of a high-profile auto racing event each year: the Canadian Grand Prix of Formula One (F1) racing. This race takes place on the famous Circuit Gilles Villeneuve on Île Notre-Dame. In 2009, the race was dropped from the Formula One calendar, to the chagrin of some fans,[195] but the Canadian Grand Prix returned to the Formula 1 calendar in 2010. The Circuit Gilles Villeneuve also hosted a round of the Champ Car World Series from 2002–2007, and was home to the NAPA Auto Parts 200, a NASCAR Nationwide Series race, and the Montréal 200, a Grand Am Rolex Sports Car Series race.

Uniprix Stadium, built in 1993 on the site of Jarry Park, is used for the Rogers Cup men's and women's tennis tournaments. The men's tournament is a Masters 1000 event on the ATP Tour, and the women's tournament is a Premier tournament on the WTA Tour. The men's and women's tournaments alternate between Montreal and Toronto every year.[196]

Montreal was the host of the 1976 Summer Olympic Games. The stadium cost $1.5 billion;[197] with interest that figure ballooned to nearly $3 billion, and was only paid off in December 2006.[198] Montreal also hosted the first ever World Outgames in the summer of 2006, attracting over 16,000 participants engaged in 35 sporting activities.

Montreal was the host city for the 17th unicycling world championship and convention (UNICON) in August 2014.

Montreal and the National Basketball Association (NBA) have been in early discussions for an expansion franchise located in the city.

| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montreal Canadiens | NHL | Ice hockey | Bell Centre | 1909 | 24 |

| Montreal Alouettes | CFL | Canadian football | Percival Molson Memorial Stadium Olympic Stadium |

1946 | 7 |

| Montreal Impact | MLS | Soccer | Saputo Stadium | 2012 | 0 |

Media

Montreal is Canada's second-largest media market, and the centre of francophone Canada's media industry.

There are four over-the-air English-language television stations: CBMT-DT (CBC Television), CFCF-DT (CTV), CKMI-DT (Global) and CJNT-DT (Citytv). There are also five over-the-air French-language television stations: CBFT-DT (Ici Radio-Canada), CFTM-DT (TVA), CFJP-DT (V), CIVM-DT (Télé-Québec), and CFTU-DT (Canal Savoir).

Montreal has three daily newspapers, the English-language Montreal Gazette and the French-language Le Journal de Montréal, and Le Devoir; another French-language daily, La Presse, became an online daily in 2018. There are two free French dailies, Métro and 24 Heures. Montreal has numerous weekly tabloids and community newspapers serving various neighbourhoods, ethnic groups and schools.

Government

The head of the city government in Montreal is the mayor, who is first among equals in the city council.

The city council is a democratically elected institution and is the final decision-making authority in the city, although much power is centralized in the executive committee. The council consists of 65 members from all boroughs.[199] The council has jurisdiction over many matters, including public security, agreements with other governments, subsidy programs, the environment, urban planning, and a three-year capital expenditure program. The council is required to supervise, standardize or approve certain decisions made by the borough councils.

Reporting directly to the council, the executive committee exercises decision-making powers similar to those of the cabinet in a parliamentary system and is responsible for preparing various documents including budgets and by-laws, submitted to the council for approval. The decision-making powers of the executive committee cover, in particular, the awarding of contracts or grants, the management of human and financial resources, supplies and buildings. It may also be assigned further powers by the city council.

Standing committees are the prime instruments for public consultation. They are responsible for the public study of pending matters and for making the appropriate recommendations to the council. They also review the annual budget forecasts for departments under their jurisdiction. A public notice of meeting is published in both French and English daily newspapers at least seven days before each meeting. All meetings include a public question period. The standing committees, of which there are seven, have terms lasting two years. In addition, the City Council may decide to create special committees at any time. Each standing committee is made up of seven to nine members, including a chairman and a vice-chairman. The members are all elected municipal officers, with the exception of a representative of the government of Quebec on the public security committee.

The city is only one component of the larger Montreal Metropolitan Community (Communauté Métropolitaine de Montréal, CMM), which is in charge of planning, coordinating, and financing economic development, public transportation, garbage collection and waste management, etc., across the metropolitan area. The president of the CMM is the mayor of Montreal. The CMM covers 4,360 km2 (1,680 sq mi), with 3.6 million inhabitants in 2006.[200]

Montreal is the seat of the judicial district of Montreal, which includes the city and the other communities on the island.[201]

Crime

The overall crime rate in Montreal has declined, with a few notable exceptions, with murders at the lowest rate since 1972 (23 murders in 2016).[202] Sex crimes have increased 14.5 percent between 2015 and 2016 and fraud cases have increased by 13 percent over the same period.[202] The major criminal organizations active in Montreal are the Rizzuto crime family, Hells Angels and West End Gang.

Education

With four universities, seven other degree-awarding institutions, and 12 CEGEPs in an 8 km (5.0 mi) radius, Montreal has the highest concentration of post-secondary students of all major cities in North America (4.38 students per 100 residents, followed by Boston at 4.37 students per 100 residents).[203]

Higher education (English)

- McGill University is one of Canada's leading post-secondary institutions, and widely regarded as a world-class institution. In 2015, McGill was ranked as the top University in Canada for the eleventh consecutive year by Macleans,[204] and as the best University in Canada; 24th best University in the world, by the QS World University Rankings.[205]

- Concordia University was created from the merger of Sir George Williams University and Loyola College in 1974.[206] The university has been ranked as one of the most comprehensive universities in Canada by Macleans.[207]

Higher education (French)

- Université de Montréal (UdeM) is the second largest research university in Canada and ranked as one of the top universities in Canada. Two separate institutions are affiliated to the university: the École Polytechnique de Montréal (School of Engineering) and HEC Montréal (School of Business). HEC Montreal was founded in 1907 and is considered as one of the best business schools in Canada.[208]

- Université du Québec à Montréal (UQaM) is the Montreal campus of Université du Québec. UQaM generally specializes in liberal-arts, although many programs related to the sciences are available.

- The Université du Québec network also has three separately run schools in Montréal, notably the École de technologie supérieure (ETS), the École nationale d'administration publique (ÉNAP) and the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS).

- L'Institut de formation théologique de Montréal des Prêtres de Saint-Sulpice (IFTM) specializes in theology and philosophy.

- Conservatoire de musique du Québec à Montréal offers both a Bachelor and a Master program in classical music.

Additionally, two French-language universities, Université de Sherbrooke and Université Laval have campuses in the nearby suburb of Longueuil on Montreal's south shore. Also, l'Institut de pastorale des Dominicains is Montreal's university centre of Ottawa's Collège Universitaire Dominicain/Dominican University College. The Faculté de théologie évangélique is Nova Scotia's Acadia University Montreal based serving French Protestant community in Canada by offering both a Bachelor and a Master program in theology

The education system in Quebec is different from other systems in North America. Between high school (which ends at grade 11) and university students must go through an additional school called CEGEP. CEGEPs offer pre-university (2-years) and technical (3-years) programs. In Montreal, seventeen CEGEPs offer courses in French and five in English.

English-language elementary and secondary public schools on Montreal Island are operated by the English Montreal School Board and the Lester B. Pearson School Board.[209][210] French-language elementary and secondary public schools in Montreal are operated by the Commission scolaire de Montréal (CSDM),[211] Commission scolaire Marguerite-Bourgeoys (CSMB)[212] and the Commission scolaire Pointe-de-l'Île (CSPI).[213]

Transportation

Like many major cities, Montreal has a problem with vehicular traffic congestion. Commuting traffic from the cities and towns in the West Island (such as Dollard-des-Ormeaux and Pointe-Claire) is compounded by commuters entering the city that use twenty-four road crossings from numerous off-island suburbs on the North and South Shores. The width of the Saint Lawrence River has made the construction of fixed links to the south shore expensive and difficult. There are presently four road bridges (including two of the country's busiest) along with one bridge-tunnel, two railway bridges, and a Metro line. The far narrower Rivière des Prairies to the city's north, separating Montreal from Laval, is spanned by nine road bridges (seven to the city of Laval and two that span directly to the north shore) and a Metro line.

The island of Montreal is a hub for the Quebec Autoroute system, and is served by Quebec Autoroutes A-10 (known as the Bonaventure Expressway on the island of Montreal), A-15 (aka the Decarie Expressway south of the A-40 and the Laurentian Autoroute to the north of it), A-13 (aka Chomedey Autoroute), A-20, A-25, A-40 (part of the Trans-Canada Highway system, and known as "The Metropolitan" or simply "The Met" in its elevated mid-town section), A-520 and A-720 (aka the Ville-Marie Autoroute). Many of these Autoroutes are frequently congested at rush hour.[214] However, in recent years, the government has acknowledged this problem and is working on long-term solutions to alleviate the congestion. One such example is the extension of Quebec Autoroute 30 on Montreal's south shore, which will serve as a bypass.[215]

Société de transport de Montréal

Public local transport is served by a network of buses, subways, and commuter trains that extend across and off the island. The subway and bus system are operated by the Société de transport de Montréal (STM, Montreal Transit Society). The STM bus network consists of 203 daytime and 23 nighttime routes. STM bus routes serve 1,347,900 passengers on an average weekday in 2010.[216] It also provides adapted transport and wheelchair-accessible buses.[217] The STM won the award of Outstanding Public Transit System in North America by the APTA in 2010. It was the first time a Canadian company won this prize.

The Metro was inaugurated in 1966 and has 68 stations on four lines.[218] It is Canada's busiest subway system in total daily passenger usage, serving 1,050,800 passengers on an average weekday (as of Q1 2010).[216] Each station was designed by different architects with individual themes and features original artwork, and the trains run on rubber tires, making the system quieter than most.[219] The project was initiated by Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau, who later brought the Summer Olympic Games to Montreal in 1976. The Metro system has long had a station on the South Shore in Longueuil, and in 2007 was extended to the city of Laval, north of Montreal, with three new stations.[220] The metro has recently been modernizing its trains, purchasing new Azur models with inter-connected wagons.[221]

Air

Montreal has two international airports, one for passengers only, the other for cargo. Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport (also known as Dorval Airport) in the City of Dorval serves all commercial passenger traffic and is the headquarters of Air Canada[222] and Air Transat.[223] To the north of the city is Montreal Mirabel International Airport in Mirabel, which was envisioned as Montreal's primary airport but which now serves cargo flights along with MEDEVACs and general aviation and some passenger services.[224][225][226][227][228] In 2018, Trudeau was the third busiest airport in Canada by passenger traffic and aircraft movements, handling 19.42 million passengers,[229][230] and 240,159 aircraft movements.[231] With 63% of its passengers being on non-domestic flights it has the largest percentage of international flights of any Canadian airport.[232]

It is one of Air Canada's major hubs and operates on average approximately 2,400 flights per week between Montreal and 155 destinations, spread on five continents.

Airlines servicing Trudeau offer year-round non-stop flights to five continents, namely Africa, Asia, Europe, North America and South America.[233][234][235] It is one of only two airports in Canada with direct flights to five continents or more.

Rail

Montreal-based Via Rail provides rail service to other cities in Canada, particularly to Quebec City and Toronto along the Quebec City – Windsor Corridor. Amtrak, the U.S. national passenger rail system, operates its Adirondack daily to New York. All intercity trains and most commuter trains operate out of Central Station.

Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), headquartered in Calgary, Alberta, was founded here in 1881.[236] Its corporate headquarters occupied Windsor Station at 910 Peel Street until 1995.[139] With the Port of Montreal kept open year-round by icebreakers, lines to Eastern Canada became surplus, and now Montreal is the railway's eastern and intermodal freight terminus.[237] CPR connects at Montreal with the Port of Montreal, the Delaware and Hudson Railway to New York, the Quebec Gatineau Railway to Quebec City and Buckingham, the Central Maine and Quebec Railway to Halifax, and CN Rail. The CPR's flagship train, The Canadian, ran daily from Windsor Station to Vancouver, but all passenger services have since been transferred to Via Rail Canada. Since 1990, The Canadian has terminated in Toronto.

Montreal-based Canadian National Railways (CN) was formed in 1919 by the Canadian government following a series of country-wide rail bankruptcies. It was formed from the Grand Trunk, Midland and Canadian Northern Railways, and has risen to become CPR's chief rival in freight carriage in Canada.[238] Like the CPR, CN has divested itself of passenger services in favour of Via Rail Canada.[239] CN's flagship train, the Super Continental, ran daily from Central Station to Vancouver and subsequently became a Via train in the late 1970s. It was eliminated in 1990 in favour of rerouting The Canadian.

The commuter rail system is managed and operated by Exo, and reaches the outlying areas of Greater Montreal with six lines. It carried an average of 79,000 daily passengers in 2014, making it the seventh busiest in North America following New York, Chicago, Toronto, Boston, Philadelphia, and Mexico City.[240]

On 22 April 2016 the forthcoming automated rapid transit system, the Réseau express métropolitain, was unveiled. Groundbreaking occurred 12 April 2018, and construction of the 67-kilometre-long (42 mi) network – consisting of three branches, 26 stations, and the conversion of the region's busiest commuter railway – commenced the following month. To be opened in three phases as of 2021, the REM will be completed by mid-2023, becoming the fourth largest automated rapid transit network after the Dubai Metro, the Singapore Mass Rapid Transit, and the Vancouver SkyTrain. Most of it will be financed by pension fund manager Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec.[241]

Notable people

International relations

Sister cities

.svg.png)

See also

- Largest cities in the Americas

- List of bridges to the Island of Montreal

- List of census metropolitan areas and agglomerations in Canada

- List of communities in Quebec

- List of mayors of Montreal

- List of metropolitan areas in the Americas

- List of Montreal music venues

- List of regions of Quebec

- List of rivers and water bodies of Montreal Island

- List of shopping malls in Montreal

- List of tallest buildings in Montreal

Notes

- Extreme high and low temperatures in the table below are from Montreal McGill (July 1871 to March 1993) and McTavish (July 1994 to present).

References

- "Quebec's Metropolis 1960–1992". Montreal Archives. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- Gagné, Gilles (May 31, 2012). "La Gaspésie s'attable dans la métropole". Le Soleil (in French). Quebec City. Archived from the original on June 5, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- Leclerc, Jean-François (2002). "Montréal, la ville aux cent clochers : regards des Montréalais sur leurs lieux de culte". Éditions Fides (in French). Quebec City.

- "Lonely Planet Montreal Guide – Modern History". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on January 5, 2007. Retrieved December 12, 2006.

- 66023 / Geographic code 66023 in the official Répertoire des municipalités (in French)

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census; Montreal, Ville [Census subdivision], Quebec and Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "(Code 0547) Census Profile". 2011 census. Statistics Canada. 2012.

- "(Code 462) Census Profile". 2011 census. Statistics Canada. 2012.

- "(Code 2466) Census Profile". 2016 census. Statistics Canada. 2017.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "(Code 462) Census Profile". 2016 census. Statistics Canada. 2017.

- Poirier, Jean. "Island of Montréal". Natural Resources Canada. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- "Global city GDP 2014". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- "Old Montréal / Centuries of History". April 2000. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- "Mount Royal Park – Montreal's Mount Royal Park or Parc du Mont-Royal". montreal.about.com. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- "Island of Montreal". Natural Resources Canada. Archived from the original on May 31, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2008.

- Poirier, Jean (1979). "Île de Montréal". 5 (1). Quebec: Canoma: 6–8. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Chapter 1, article 1, "Charte de la Ville de Montréal" (in French). 2008. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Chapter 1, article 1, "Charter of Ville de Montréal". 2008. Archived from the original on December 26, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- Discovering Canada Archived November 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (official Canadian citizenship test study guide)

- "Living in Canada: Montreal, Quebec". Abrams & Krochak – Canadian Immigration Lawyers. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2009.

- Roussopoulos, Dimitrios; Benello, C. George, eds. (2005). Participatory Democracy: Prospects for Democratizing Democracy. Montreal; New York: Black Rose Books. p. 292. ISBN 978-1-55164-224-6. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2009. Quote: Montreal "is second only to Paris as the largest primarily French-speaking city in the world".

- Kinshasa and Abidjan are sometimes said to rank ahead of Montreal as francophone cities, since they have larger populations and are in countries with French as the sole official language. However, French is uncommon as a mother tongue there. According to Ethnologue, there were 17,500 mother-tongue speakers of French in the Ivory Coast as of 1988. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=fra Archived October 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Approximately 10% of the population of Congo-Kinshasa knows French to some extent. http://www.tlfq.ulaval.ca/AXL/afrique/czaire.htm Archived November 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "City of Toronto, History Resources". City of Toronto. October 23, 2000. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- "Why Choose Montréal – Montreal International". Montreal International. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- "Montreal, Canada appointed a UNESCO City of Design" (PDF). UNESCO. June 7, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- Wingrove, Josh (June 9, 2008). "Vancouver and Montreal among 25 most livable cities". Globe and Mail. Canada. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- "Montreal Ranked Top Most Livable City". Herald Sun. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

The EIU's annual report, which ranks 140 major cities around the world based on their liveability, found Melbourne, Australia to be the most liveable city in the world. [...] Montreal doesn't make the list until number 12

- "QS Best Student Cities 2017". Top Universities. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Montreal 1976". Olympic.org. Archived from the original on January 4, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- www.ixmedia.com. "Articles | Encyclopédie du patrimoine culturel de l'Amérique française – histoire, culture, religion, héritage". www.ameriquefrancaise.org (in French). Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- "The World According to GaWC". 2018. Archived from the original on May 3, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- "Circuit Gilles Villeneuve". Circuit Gilles Villeneuve Official Website. Archived from the original on December 24, 2015. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- "About – Festival International de Jazz de Montréal". www.montrealjazzfest.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- "Just For Laughs Festival". www.tourisme-montreal.org. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- "Onishka – Art et Communaute". Archived from the original on February 20, 2016.

- Kalbfleisch, John (May 17, 2017). "Founding of Ville-Marie". Canada's National History Society. Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- "how should one pronounce montreal? a historical and linguistic guide". July 15, 2009. Archived from the original on August 26, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- "Natural Resources Canada, Origins of Geographical Names: Island of Montréal". Archived from the original on July 3, 2013.

- Centre d'histoire de Montréal. Le Montréal des Premières Nations. 2011. P. 15.

- "Place Royale and the Amerindian presence". Société de développement de Montréal. September 2001. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- Tremblay, Roland (2006). The Saint Lawrence Iroquoians. Corn People. Montréal, Québec, Canada: Les Éditions de l'Homme.

- Bruce G. Trigger, "The Disappearance of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians" Archived May 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, in The Children of Aataenstic: A History of the Huron People to 1660, vol. 2, Montreal and London: Mcgill-Queen's University Press, 1976, pp. 214–218, accessed February 2, 2010

- Marsan, Jean-Claude (1990). Montreal in evolution. An historical analysis of the development of Montreal's architecture. Montréal, Qc: Les Éditions de l'Homme.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Miquelon, Dale. "Ville-Marie (Colony)". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- Beacock Fryer, Mary (1986). Battlefields of Canada. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-55002-007-6. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- "Alanis Obomsawin, Kanesatake: 270 Years of Resistance, National Film Board of Canada, 1993, accessed Jan 30, 2010". National Film Board of Canada. February 5, 2010. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- "Articles of the Capitulation of Montréal, 1760". MSN Encarta. 1760. Archived from the original on November 1, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- Atherton, William Henry (1914). Montreal: 1535–1914. S. J. Clarke publishing Company. p. 57. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- "Montreal :: Government". Student's Encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- "Lachine Canal National Historic Site of Canada" (PDF). Parks Canada. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- "Visiting Montréal, Canada". International Conference on Aquatic Invasive Species. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- "UNA-Canada: A Sense of Belonging". United Nations Association in Canada. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- Anderson, Letty. "Water-supply." Building Canada: A History of Public Works. By Norman R. Ball. Toronto: U of Toronto, 1988. 195–220. Print.

- Dagenais, Michèle. "The Urbanization of Nature: Water Networks and Green Spaces in Montreal." Method and Meaning in Canadian Environmental History (2009): 215–35. Niche. Web. Mar. 2016.