Sikhism in Canada

Canadian Sikhs number roughly 500,000 people[1] and account for roughly 1.4% of Canada's population.[2] Canadian Sikhs are often credited for paving the path to Canada for all South Asian immigrants as well as for inadvertently creating the presence of Sikhism in the United States. Sikhism is a world religion with 27 million followers worldwide, with majority of their population in Punjab, India.[3] The Legislative Assembly of Ontario celebrates April as Sikh Heritage Month.[4][5]

Nanaksar Gurdwara Sahib (Sikh Temple), Edmonton, Alberta | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 468,670 (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Sikhism |

| Part of a series on |

| Sikhism |

|---|

|

|

|

Practices

|

|

|

General topics

|

The largest Sikh populations in Canada are found in British Columbia, followed by Ontario and then Alberta.[6] However, Sikhs can be found in every province and territory within the country.[6] As of the 2011 Census, more than half of Canada's Sikhs can be found in one of four cities: Surrey (105,000), Brampton (97,800), Calgary (28,600), and Abbotsford (26,000).[7] British Columbia holds the distinction of being the only province or jurisdiction outside of South Asia with Sikhism as the second most followed religion among the population.[8]

Population

According to the 2011 National Household Survey, the number of Sikhs living in each of the Canadian provinces and territories is as shown in the following table. Unlike in India, Sikhs form the main religious group among South Asian immigrants in Canada. In India, Sikhs comprise 1.72% of the population, while Hindus make up the largest religious group at close to 79.8%. Among the Indo-Canadian population, the religious views are more evenly divided with Sikhs representing 28% and Hindus 28%.[9]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 94,803 | — |

| 1991 | 192,608 | +103.2% |

| 2001 | 319,802 | +66.0% |

| 2011 | 455,000 | +42.3% |

| Province | Sikhs in 2001 | % 2001 | Sikhs in 2011 | % 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 135,310 | 3.9% | 201,110 | 4.7% | |

| 104,790 | 0.9% | 179,760 | 1.4% | |

| 23,470 | 0.8% | 52,300 | 1.5% | |

| 5,485 | 0.5% | 10,200 | 0.9% | |

| 8,225 | 0.1% | 9,280 | 0.1% | |

| 495 | 0.1% | 1,660 | 0.2% | |

| 265 | 0.1% | 385 | 0.0% | |

| 130 | 0.0% | 100 | 0.0% | |

| 105 | 0.4% | 90 | 0.3% | |

| 90 | 0.0% | 15 | 0.0% | |

| 45 | 0.1% | 15 | 0.0% | |

| 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 0.0% | |

| 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 0.0% | |

| 319,802 | 0.9% | 455,000 | 1.4% |

Neighbourhoods

Prominent Sikh neighbourhoods exist in many of Canada's major cities, and their suburbs.[10]

British Columbia is home to not only the largest population of Sikhs in the country, but also some of the longest established Sikh communities. Although Sikhs can be found in most towns and cities within the province - most are concentrated in the Lower Mainland. In the city of Vancouver, Sikhs form over 30% of the population in the Sunset neighbourhood, with the traditional Punjabi Market being the epicenter of Vancouver's Sikh community. In Vancouver's suburb of Surrey, Sikhs form a majority in the Newton and Whalley neighbourhoods. Surrey's Sikhs can be found in large numbers across the city, with the exception of South Surrey. Sikhs in New Westminister can be found in the Queensborough area, where they are upwards of 30% of the population, and have lived since 1919.[11] The west side of Abbotsford similarly hosts a large Sikh community, forming over 60% of the population in some parts of the Clearbook and Townline Hill areas. Similar to New Westminster, the establishment of Abbotsford's Sikh community goes back generations to 1905.[12] The southern half of Oliver, BC, a small town in the Okanagan Valley, also has a Sikh population above 40%.[13][14]

Sikh communities are found in most cities and towns in Southern Ontario, while few are found living north of Barrie. The Greater Toronto Area is home to the second largest community of Sikhs in Canada, after the Vancouver-Abbotsford area of British Columbia. Sikhs in Toronto traditionally lived in the Rexdale neighbourhood of Etobicoke, and Armadale in Scarborough. An older established Sikh community can be found in Malton, Mississauga as well, where Sikhs form nearly 25% of the population.[15] Over half of Ontario's Sikhs can be found in Brampton, where they account for 19% of the city's total population.[16] While Sikhs can be found living in all parts of Brampton, they form upwards of 35% of the population in the neighbourhoods of Churchville, Springdale and Castlemore.

In Alberta, most of the province's Sikhs live in either Calgary or Edmonton. Although many are first or second generation immigrants, Sikhs have lived in Calgary since at least 1908.[17] The majority of Sikhs in Calgary are concentrated in the Northeast section of the city.[18] Sikhs form over 20% of the population in some Northeast Calgary neighbourhoods, particularly Martindale, Taradale, Coral Springs and Saddle Ridge. Most of Edmonton's Sikhs can be found in the Southeast section of the city, particularly The Meadows, and Mill Woods.[19] In The Meadows neighbourhood of Edmonton, Sikhs form over 30% of the population of Silver Berry.

The Sikh community in Manitoba is small at 0.9%, and largely concentrated in Winnipeg. Within Winnipeg, there are no established Sikh neighbourhoods, although The Maples and Mandalay West in the far north end of the city are over 10% Sikh.

Quebec is home to a more educated, upper-middle class Sikh community. Virtually the entire Sikh population of Quebec is found in the Montreal area. In the Montreal area, working class Sikhs are found in Park Extension, while wealthier Sikh families can be found in Dollard-des-Ormeaux, and LaSalle, Quebec.

History

Early immigration

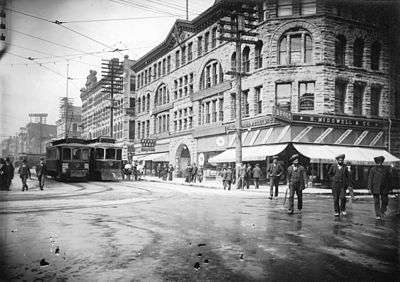

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Kesur Singh, a Risaldar Major in the British India Army, is credited with being the first Sikh settler in Canada.[20] He was amongst a group of Sikh officers who arrived in Vancouver on board Empress of India in 1897.[21] They were on the way to Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee. Sikhs found employment in laying the tracks of the Canadian Pacific Railway, in lumber mills and mines. Though they earned less than white workers, they made enough money to send some of it to India and make it possible for their relatives to immigrate to Canada. The first Sikh pioneers came to the Abbotsford area in 1905 and originally worked on farms and in the lumber industry.[12] By 1906, there were about 1,500 Sikh workers living in Canada, among about 5,000 East Indians in total. Although most of the immigrants from South Asia at the time were Sikhs, local ignorance of Eastern religions led to them frequently being assumed to be Hindus. About 90% of these Sikhs lived in British Columbia. While Canadian politicians, missionaries, unions and the press were opposed to Asian workers[22] British Columbia industrialists were short of labour and thus Sikhs were able to get an early foothold at the turn of the 20th century in British Columbia.

As with the large numbers of Japanese and Chinese workers already present in Canada, many white workers resented those immigrants and directed their ill-will toward the Sikhs, who were easily recognized by their beards and turbans. Punjabis were accused of having a caste system, an idea that goes against the foundations of Sikhism. They were portrayed as being riddled with trachoma and as being unclean in general. To strengthen these racist characterizations, a song called White Canada Forever was created. All this eventually led to a boat of Sikhs arriving in Vancouver being sent to Victoria. In 1907, the year that Buckam Singh came to British Columbia from Punjab at the age of fourteen, Punjabis were forced to avoid the Anti-Oriental Riots of 1907 by staying indoors.

Most of the Sikhs in Canada in 1907 were retired British army veterans and their families.[23]

.jpg)

These Punjabis had proved themselves as loyal soldiers in the British colonies in Asia and Africa. However, the Canadian Government did not prevent the use of the illegal scare tactics being used to monitor immigration and prevent Sikhs from seeking employment, and this soon resulted in the cessation of all Indian immigration to Canada. The Canadian Prime Minister, Sir Wilfrid Laurier claimed that Indians were unsuited to life in the Canadian climate. However, in a letter to the viceroy, The Earl of Minto, Sir Wilfred voiced a different opinion, stating that the Chinese were the least adaptable to Canadian ways, whereas Sikhs, which he mistakenly referred to as Hindus, were the most adaptable. Nevertheless, 1,072 Sikhs left for California in 1907. In the same year, the Khalsa Diwan society was set up in Vancouver with branches in Abbotsford, New Westminster, Fraser Mills, Duncan Coombs and Ocean Falls.

In 1908, Indians were asked by the Canadian Government to leave Canada voluntarily and settle in British Honduras; it was stated that the "Mexican" climate would better suit Indians. A Sikh delegate was sent to what is now Belize and stayed in the British colony for some time before returning. Upon his return, he advised not only Sikhs, but also the members of other Indian religious groups, to decline the offer, maintaining that conditions in Latin America were unsuitable for Punjabis, although they might be more amenable to South Indians. In 1908, 1,710 Sikhs left British Columbia for California. The first plans to build a temple were made in 1908. After a property was acquired, the settlers carried lumber from a local mill on their backs up a hill to construct a gurdwara.[12]

William Lyon Mackenzie King (not yet the Canadian Prime Minister) visited London and Calcutta to express the Canadian view of Indian immigration. As a result, the Indian Government stopped advertising facilities and employment opportunities in North America. This invoked the provisions of Emigration act of 1883 which stopped Sikhs from leaving Canada. The Canadian Government passed two laws, one providing that an immigrant had to have 200 dollars, a steep increase from the previous requirement of 20 dollars, the other authorizing the Minister of the Interior to prohibit entry into Canada to people not arriving from their birth-country by continuous journey and through tickets purchased before leaving the country of their birth or citizenship. These laws were specifically directed at Punjabis and resulted in their population, which had exceeded 5,000 people in 1911, dropping to little more than 2,500.

The Immigration Act, 1910 came under scrutiny when a party of 39 Indians, mostly Sikhs, arriving on a Japanese ship, the Komagata Maru, succeeded in obtaining habeas corpus against the immigration department's order of deportation. The Canadian Government then passed a law intended to keep labourers and artisans, whether skilled or unskilled, out of Canada by preventing them from landing at any dock in British Columbia. As Canadian immigration became stricter, more Indians, most of them Sikhs, travelled south to the United States of America. The Gur Sikh Temple opened on February 26, 1911; Sikhs and non-Sikhs from across British Columbia attended the ceremony and a local newspaper reported on the event. It was the first Gurdwara not only in North America, but also anywhere in the world outside of South Asia, and has since become a Canadian historical landmark and symbol, the only Gurdwara to have similar status outside India. The Khalsa Diwan Society subsequently built Gurdwaras in Vancouver and Victoria.[24] The first and only Sikh settlement in Canada, Paldi, British Columbia was established as a mill town in 1916.[25]

Though the objectives of the Khalsa Diwan Society were religious, educational and philanthropic, problems connected to immigration and racism loomed in its proceedings. Alongside the Sikh Diwan, other organizations were set up to counteract the policies of the immigration authorities. The United India League operated in Vancouver, and the Hindustani Association of the Pacific Coast opened in Portland, Oregon. Gurdwaras became storm centres of political activity. The Ghadar Party was founded in America in 1913 by Sikhs who had fled to California from British Columbia as a consequence of Canadian immigration rules. Despite originally being directed at the racism encountered by Sikhs in the Sacramento Valley and in Sacramento itself, it eventually moved to British Columbia. Thousands of Ghadar journals were published with some even being sent to India.

The Komagata Maru incident

In 1908, a series of ordinances were passed by the federal government, by which Indian immigrants entering Canada had to have 200 Canadian dollars (vs. 25 for Europeans). They also had to arrive directly from the area of birth/nationality- even though there was no direct route between India and Canada. Because of this legislation, in 1914, a Japanese ship called Komagata Maru chartered by a Sikh businessman which sailed from Hong Kong to Vancouver (with multiple stops) was not allowed to dock at the final port. The ship, which had 376 passengers (340 Sikhs), had to spend over 2 months offshore and only 20 former Canadian residents were allowed to disembark.[26]

In 1914, Buckam Singh moved to Toronto. Also in 1914, Gurdit Singh Sandhu, from Sarhali, Amritsar, was a well-to-do businessman in Singapore who was aware of the problems that Punjabis were having in getting to Canada due to exclusion laws. He initially wanted to circumvent these laws by hiring a boat to sail from Calcutta to Vancouver. His aim was to help his compatriots whose journeys to Canada had been blocked. In order to achieve his goal, Gurdit Singh purchased the Komagata Maru, a Japanese vessel. Gurdit Singh carried 340 Sikhs, 24 Muslims, and 12 Hindus in his boat to Canada.

When the ship arrived in Canada, it was not allowed to dock. The Conservative Premier of British Columbia, Richard McBride, issued a categorical statement that the passengers would not be allowed to disembark. Meanwhile, a "Shore Committee" had been formed with the participation of Hussain Rahim and Sohan Lal Pathak. Protest meetings were held in Canada and the USA. At one, held in Dominion Hall, Vancouver, it was resolved that if the passengers were not allowed off, Indo-Canadians should follow them back to India to start a rebellion (or Ghadar). The shore Committee raised $22,000 dollars as an instalment on chartering the ship. They also launched a test case legal battle in the name of Munshi Singh, one of the passengers. Further, the Khalsa Diwan Society (founded 1907 to manage Vancouver's gurudwara) offered to pay the 200 dollar admittance fee for every passenger, which was denied.[27] On July 7, the full bench of the Supreme Court gave a unanimous judgment that under new Orders-In-Council it had no authority to interfere with the decisions of the Department of Immigration and Colonization. The Japanese captain was relieved of duty by the angry passengers, but the Canadian government ordered the harbour tug Sea Lion to push the ship out on its homeward journey. On July 19, the angry passengers mounted an attack. Next day the Vancouver newspaper The Sun reported: "Howling masses of Hindus showered policemen with lumps of coal and bricks... it was like standing underneath a coal chute".

The Komagata Maru arrived in Calcutta, India on September 26. Upon entry into the harbour, the ship was forced to stop by a British gunboat and with the passengers subsequently being placed under guard. The ship was then diverted approximately 27 kilometres (17 miles) to Budge Budge, where the British intended to put them on a train bound for Punjab. The passengers wanted to stay in Calcutta, and marched on the city, but were forced to return to Budge Budge and re-board the ship. The passengers protested, some refusing to re-board, and the police opened fire, killing 20 and wounding nine others. This incident became known as the Budge Budge Riot. Gurdit Singh managed to escape and lived in hiding until 1922. He was urged by Mohandas Gandhi to give himself up as a true patriot. He was imprisoned for five years.

First World War

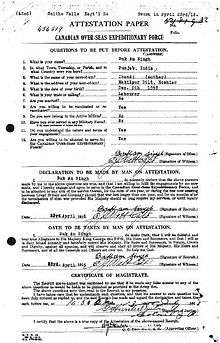

Buckam Singh enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force in the spring of 1915.[28] Buckam Singh was one of the earliest known Sikhs living in Ontario at the time as well as one of only 9 Sikhs known to have served with Canadian troops in the First World War. Private Buckam Singh served with the 20th Canadian Infantry Battalion in the battlefields of Flanders during 1916. Here, Buckam Singh was wounded twice in battle and later received treatment at a hospital run by one of Canada's most famous soldier poets the Doctor Lt. Colonel John McCrae.

While recovering from his wounds in England, Private Buckam Singh contracted tuberculosis and spent his final days in a Kitchener, Ontario military hospital, dying at age 25 in 1919. His grave in Kitchener is the only known First World War Sikh Canadian soldier's grave in Canada. Despite being forgotten for ninety years and never getting to see his family again, Buckam Singh is now being celebrated as not only a Sikh hero, but a Canadian hero.[29]

Growing government support

Due to immigration restrictions, South Asians were not able to bring their relatives from India to Canada. Therefore, they resorted to illegal means to bring them to Canada. This was through the Washington-British Columbia border. When the Canadian Government became aware of the happenings along the borderline, they tightened immigration regulations and South Asian men who stayed even three days longer outside of Canada were denied entrance for violating the three-year limit. In 1937, a controversy surfaced with there being almost three hundred illegal South Asian immigrants in BC. The case was investigated by the RCMP who had eventually solved the case. The Canadian government, however, decided to take this as an opportunity to negotiate with India and refused to deport illegal Sikh immigrants. In fact, the Canadian government pushed the Sikhs into gaining residency in Canada. During the 1940s, South Asians in Canada began to establish their livelihoods despite deep social and economic disturbances. Unemployment was common and the average British Columbian's wage had dropped over 20 percent. White employers were willing to accept Asian workers, this produced insecurities amongst the mainstream community of British Columbia. The result of this was a British Columbia minimum wage law, a law that was ultimately flawed. 25 percent of the employees would be paid 25 percent less and these were invariably Asians. South Asians continued to live under one roof and in extensive families; this support helped them during the Depression period.[30]

In 1943, a twelve-man delegation including members of the Khalsa Diwan Society presented the case of South Asian voting rights to Premier Hart. They said that without the ability to vote, in Canada they were nothing more than second-class citizens. The Premier then made it so that South Asians in British Columbia that had fought in World War II would be granted voting rights, this law was passed in 1945. By 1947, all South Asians had the right to vote due to the Sikh Khalsa Diwan Society. In 1944, the Canadian Census showed there to be 1756 Canadian Sikhs with 98% of them living in British Columbia, the initial major port of immigration for Canadian Sikhs.[31]

It was in the 1950s that major immigration to Ontario would start to occur. The celebration of the birth of Guru Nanak was first celebrated in 1954 after a group of Sikhs from England arrived because of the liberalization of the laws due to the acts of the Khalsa Diwan Society. The construction of many gurdwaras had an immense effect on the Sikh population in Ontario.[32] Following the founding of the East Indian Welfare Association by Sikhs, the first ever Sikh was elected to a city council in Mission, B.C. It was reported the following year that there were 2148 Sikhs in Canada.[33]

New era

In the 1960s and 1970s, tens of thousands of skilled Sikhs, some highly educated, settled across Canada, especially in the urban corridor from Toronto to Windsor. As their numbers grew, Sikhs established temporary gurdwaras in every major city eastward to Montréal, with the first gurdwara in Eastern Canada being made in 1965. These were followed in many instances by permanent gurdwaras and Sikh centres. Most cities now have several gurdwaras, each reflecting slightly different religious views, social or political opinions. Through them, Sikhs now have access to a full set of public observances. Central among these are Sunday prayer services, and in many communities the prayers are followed by langar (a free meal) provided by members of the sangat (governing council of holy men) and the congregation. The Khalsa Diwan Society grew to a much larger amount during the immigration boom of this period. Near the end of the decade in 1979, the Canadian Sikhs, now more racially diverse, celebrated the 500th birthday of Guru Amar Das to mark the start of the annual Nagar Kirtan's, which would occur in Canada every year following. To celebrate the centennial birthday of the guru, the Khalsa Diwan Society purchased an adjoined building which included a school, museum, daycare and Gurdwara and named it after Guru Amar Das. In the early 1980s, the Khalsa Diwan Society grew slightly more and built a sports complex. Canada would also have its first officially registered Sikh organization, the Federation of Sikh Societies of Canada in the early 1980s. In the months prior to Operation Blue Star, Sikh seats were granted to the University of British Columbia and the University of Toronto. The launching of Operation Bluestar enraged many Sikhs in Canada, who had left their homeland long ago in search of better prospects.[33][34]

Sikh Insurgency

Militancy

Extremism in Canada increased after the Operation Bluestar to evict militant leader Bhindranwale occupying the Akal Takht inside the Golden Temple, the holiest shrine of Sikhs, to evade arrest. Some Sikhs wanted a separate nation based on religion, called Khalistan. Khalistanis would sometimes be met by opposition by some Indians and went generally unnoticed by the Canadian Government."[35][36] Ujjal Dosanjh, a moderate Sikh, spoke against Sikh extremists and faced a "reign of terror".[37]

In Vancouver, many Sikh protests occurred. Two Sikhs entered the Indian Consulate in Vancouver and smashed all pictures of Indira Gandhi with swords. Later in the week, Sikh protesters by the hundreds blocked the entrance to the consulate, forcing it to close, then burned the Indian National Flag and an effigy of Indira Gandhi. They would spend the day chanting "Down With Gandhi" and "Gandhi is a Murderer" until the consulate had to agree to relay their demands to the Indian Government. Following their dispersion, the Sikhs spent the rest of the day mourning Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale.[38] Bhindranwale had been declared a "terrorist" by the Indian government and had brought arms and ammunition while occupying a sacred place of worship, held sacred by all Indians, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, following which Operation Bluestar was launched.

Following the closure at the Indian Consulate in Vancouver, a Sikh youth damaged the consulate in Toronto.[39] 700 Sikhs then protested in front of the Toronto consulate much like what had happened at the Vancouver consulate. At the Toronto consulate, Sikhs who had left Punjab and India for Canada, burned the Indian National Flag. Toronto Metropolitan Police Officers were recorded saying that the unity brought in Canada at this time was miraculous.[40] 2500 Sikhs had marched in the city of Calgary following the march at the Toronto consulate.[41]

Air India Flight 182 was an Air India flight operating on the Montréal-London-Delhi-Bombay route. On 23 June 1985, the airplane operating on the route was blown up in midair by a bomb in the coast of Ireland. In all, 329 people perished, among them 280 Canadian nationals, mostly of Indian birth or descent, and 22 Indian nationals. The attack was the deadliest act of aviation terrorism until the September 11 attacks in 2001.[42][43][44]

The main suspects in the bombing were the members of a Sikh separatist group called the Babbar Khalsa and other related groups who were at the time agitating for a separate State based on religion called Khalistan in Punjab, India. In September 2007, the Canadian commission investigated reports, initially disclosed in the Indian investigative news magazine Tehelka[45] that a hitherto unnamed person, Lakhbir Singh Rode had masterminded the explosions.

Civil unrest

In 1986, it was allowed by the Metro Toronto Police to have Sikhs wear turbans while on duty. Later that year, the Khalsa Credit Union was also established. In 1988, for the first time, the Canadian Parliament broached the topic of Operation Bluestar in regards to the Canadian Sikh population. In 1993, the Vancouver Punjabi Market was recognized as bilingual signs in English and Punjabi were established due to the high Sikh population in the area. In 1993, Sikhs were denied entry to the Royal Canadian Legion when invited to attend a Remembrance Day Parade.[46] In 1995, the Canadian government officially recognized the Vaisakhi Nager Kirtan parade.[47] Due to this, the civil unrest eventually began to fade as more and more cities outside of British Columbia and Ontario began to join in on the parades, including Montreal in 1998.[48]

2000s - present

Ujjal Dosanjh

Ujjal Dosanjh, who previously held several cabinet portfolios in British Columbia including Attorney General, became 33rd Premier of the province in 2000. His government was defeated in the 2001 general election. He became a federal Member of Parliament in 2004 and Minister of Health from 2004 to 2006.

Centennial year

In 2002, the Gur Sikh Temple was designated a national historic landmark by prime minister Jean Chrétien on July 26, 2002. It is the only gurdwara declared a national historic landmark outside of South Asia.[24] In 2007 the temple was completely renovated and reopened. In 2011, the Gur Sikh Temple in Abbotsford celebrated its one-hundredth birthday. To celebrate, the Government of Canada is funding the building of a museum dedicated to Canadian Sikhism. During the anniversary celebration, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper gave a speech to the Punjabi Community as to how the Gur Sikh Temple is a shrine to all immigrants into Canada, not just Sikh ones. 2011 was declared the Centennial year for Canadian Sikhs.[24]

Rajoana protests (2005–2012)

In 2005, it was announced that Balwant Singh Rajoana would be hanged under the death penalty for the murder of former Punjab Chief Minister Beant Singh on March 31 in Patiala. Balwant Singh Rajoana was considered a hero among many Sikh youths in Canada, who stated that upon death he would become a martyr. The announcement angered many Sikhs across the world. Many of these angered Sikhs were both Punjabi and converted from Canada, spurring civil unrest among Canadian Sikhs. The World Sikh Organization of Canada had called on the United Nations to try to make India abolish the death penalty and save Rajoana from death.

Upon the announcement, many Canadian Sikhs, regardless of race, took up Nishan Sahib and began to protest against the Indian government, and against the execution of Rajoana, in the city of Vancouver. Other protests happened worldwide in the United Kingdom, United States, Australia, New Zealand and even India itself. Following the release of Kishori Lal, a murderer who had decapitated three innocent Sikhs with a chopper knife, the announcement led Canadian Sikhs to believe that the Indian government was targeting Sikh people.[49] In Canada, a large protest in Edmonton took place on March 25, six days prior to the pending execution. On the last day before his impending execution, 5000 Sikhs walked in front of Parliament Hill in the capital city of Ottawa. That same day, an announcement was made that Rajoana's hanging would be stayed.[50]

The protests had gained mixed reactions, with a majority of citizens not supporting the protests of the Sikhs, seeing them as people with an unjust cause.[51] Many members of the Canadian Parliament supported the Sikh rallies and their protests against the death penalty in India. These politicians included, but were not limited to, Justin Trudeau, Parm Gill, Jasbir Sandhu, Wayne Marston, Don Davies, Kirsty Duncan and Jim Karygiannis.[52] Around this time, a group of Skinheads called "Blood and Honour" would attack two Sikh men in Edmonton.[53]

To celebrate the 2012 Vaisakhi festival, the local Sikh community decided to sponsor a new Canadian Army Cadet Corps, which was being formed by the Department of National Defence.[54] Whilst happening on April 13 in 2012, Vaisakhi was celebrated in Vancouver on April 14. The Vancouver Sun made their estimation of the Metro Vancouver Sikh population to be at 200,000 during an article about the 2012 Vaisakhi.[55] The Vancouver Vaisakhi ended up attracting thousands of people as well as various politicians including BC Premier Christy Clark.[56] At the April 21st Surrey Vaisakhi, the Sikh peoples demonstrated support for Rajoana through various posters, with large banners calling India the world's largest "Democracy". The response to the support was positive.[57]

Around this time, Sikh comedians Jasmeet Singh (JusReign), and Lilly Singh (Superwoman) would gain international fame for their videos on YouTube.[58]

In May 2012, the classic Victoria Gurdwara, which was once broken down, but later rebuilt, would experience its one hundredth anniversary. It was the second Gurdwara to celebrate one hundred years in Canada after the Gur Sikh Temple in the Sikhs' Centennial Year. The Gurdwara houses over 3000 people per month.[59] It was then announced that Sikhs would be allowed to wear kirpans in Toronto courthouses.[60] In June, a Khalsa School in Brampton would be vandalized by racists who would put up signs of the Ku Klux Klan and with swastikas.[53]

NDP Party Leader Thomas Mulcair would once again raise ire and tensions when he would bring up the 1984 Anti-Sikh Riots. Mulcair would demand that a full investigation be put into the riots and those harmed be compensated.[61] Soon after this statement, neo-Nazi gunman Wade Michael Page would commence a shooting at a Sikh Temple in Wisconsin, America, which would be described as a domestic terrorism act. Despite the fact that the shooting occurred outside of Canada, Canadian Sikhs would take full responsibility to spread the message of Sikhism, explain the religion, honour the dead and wounded as well as give their reactions to the shootings.[62]

The Indian Overseas Congress would request to the Akal Takht that all Khalistan symbols prevailing in Canadian gurdwaras be removed. They would go on to claim Pakistan funding Canadian efforts relating Khalistan and that Canadian politicians of Sikh heritage were turning militant,[63] a claim that would immediately be denied.[64] Stephen Harper is pushing back at suggestions that Ottawa needs to do more about Sikh separatist activity in Canada, saying his government already keeps a sharp lookout for terrorist threats and that merely advocating for a Khalistan homeland in the Punjab is not a crime. He said violence and terrorism can't be confused with the right of Canadians to hold and promote their political views.[65]

Following, on CKNW's Philip Till Show would feature Dave Foran, a man who would demand Canadian Sikhs to lose their religious aspects, namely turbans, beards, clothes and "waddling" while walking, claiming the features to make "real" Canadians "sick".[53] Soon after, the Friends of the Sikh Cadet Corps would run into issues with the 3300 British Columbian Royal Army Cadet, over their choice of name. The resulting turmoil would put months and months of planning into disarray.[50]

The Sikhs of Canada would once again take solidarity and hospitality, much like they had done with the Rajoana situation, to support Daljit Singh Bittu and Kulbir Singh Barapind. The two had previously been arrested and abused on false charges, resulting in their most recent arrest to raise the ire of the Canadian Sikhs, who would go on to trash the policing forces in Punjab.[66]

New Age

2013 was a monumental year for Sikhs as the April of that year was declared the Sikh Heritage Month by the Government of Ontario.[67] In 2014, history was made when a park in Calgary was named after Harnam Singh Hari, the first Sikh settler who was able to successfully farm on fertile land in Alberta. This happened shortly after the announcement of Quebec's Charter of Values, which threatened the use of religious items at government workplaces. This Charter was opposed by the Sikhs, Hindus, Jews, Christians, and Muslims whose symbols would be affected by the charter. In May 2014, Lieutenant Colonel Harjit Sajjan became the first Sikh to command a Canadian regiment, ironically it was the British Columbia Regiment (Duke Connaught's Own), which opposed the Komagata Maru a century prior.[68] In 2015, the Surrey Nagar Kirtan was declared the largest parade of its kind outside of India.[69] In August 2015, Corporal Tej Singh Aujla of the 39th Brigade Group, Royal Westminster Regiment became the first Sikh soldier to guard and watch over the "Tomb of the Unknown Soldier" at Canada's National War Memorial.[70] In regards to the 2015 Canadian election, it was internationally noted that in over twelve constituencies Sikh politicians were riding against each other, a highlight of the successful integration of the Sikh populace as Canadian citizens. It was also noted that of these politicians, Martin Singh was a Caucasian convert to Sikhism and potentially the first "white" Sikh to run for a constituency in the federal elections.[71]

In the 2015 Canadian election, twenty Sikh MPs were elected, the most ever. Of these, four Sikh MPs went on to become a part of the Cabinet of Canada under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. This marked the first time the Cabinet of Canada had more Sikhs as ministers than the Cabinet of India.[72] This disparity was acknowledged by Trudeau in March 2016.[73] Of these MPs, Bardish Chagger ended up becoming the first Sikh woman to hold a post in the Cabinet of the Prime Minister. Also, MP Lt. Col. (ret.) Harjit Singh Sajjan became the first Amritdhari Sikh to hold a Cabinet position since the Sikh Empire as Minister of National Defence.[74] That same year, Punjabi became the third most spoken language of the Parliament of Canada.[75] Concurrently, many Canadian Sikhs held solidarity with the protests of Sikhs in India following the sacrilege of the Guru Granth Sahib. Many Sikh organizations in Canada held discussions on how to address the situation in regards to Canada. Many Canadian Sikh youths took to Twitter to protest the sacrilege with the hashtag #SikhLivesMatter.[76]

On April 11, 2016, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that a formal apology for the Komagata Maru incident would finally be given after 102 years.[77]

On October 1, 2017, Jagmeet Singh, was elected leader of the federal New Democratic Party on the first ballot of that party's 2017 leadership race. Upon his election, Singh became the first Sikh and the first person of a visible minority group to be elected leader of a Canadian federal political party.[78] Previously, Singh had also held the distinction of being the first turban-wearing Sikh to sit as a provincial legislator in Ontario.[79]

By province

British Columbia

Sikhism is the second largest religion in the Greater Vancouver area where they form 6.8% of the total population.

In 2001 16,780 persons in the Abbotsford area stated that they were of the Sikh religion. In 2011 28,235 persons in the Abbotsford area stated that they were of the Sikh religion, making up 16.9% of the population.[80] Of all census metropolitan areas in Canada, Abbotsford had the highest Sikh percentage in 2011.[81]

Gur Sikh Temple is located in Abbotsford. It was the Sikh gurdwara building in North America that is still standing.[82] In 1975 the Khalsa Diwan Society of Abbotsford separated from the parent organization in Vancouver, as the title of the Abbotsford gurdwara was transferred to the separated entity. The Abbotsford Sikhs wanted to have local control over their gurdwara.[83]

The largest concentration of Sikhs in the Greater Vancouver area is in the City of Surrey in the census agglomeration's southeastern sector, forming 22.6% of the population. The City of Abbotsford which lies east of the census agglomeration's boundary, has the next-largest concentration of Sikhs in British Columbia, at 13.4% of the population (with 16.3% self-identifying of the total city population as East Indian, and 2.3% as Punjabi).[84]

Memorials

Sikh Remembrance Day

Since 2009, Sikh members of the Canadian Forces (CF) have attended the annual Sikh Remembrance Day service which is held at the Mount Hope Cemetery in Kitchener, Ontario. This cemetery holds the only military grave in Canada belonging to a Sikh soldier, Private Buckham Singh who fought in World War I. In 2012, NCdt Tejvinder Toor, OCdt Saajandeep Sarai & OCdt Sarabjot Anand represented Royal Military College of Canada at the event in uniform.[85]

Celebrations

Nagar Kirtan

Various Nagar Kirtan celebrations happen in Canada, with most starting in British Columbia. In British Columbia, various places celebrate the Nagar Kirtan, though it is mainly celebrated in the cities of Vancouver and Surrey. In Vancouver, the Nagar Kirtan, is used to celebrate the Visakhi and the birth of Khalsa. Various Canadian Sikhs, of various ethnic origins, are present in the parade, which usually happens on Easter Weekend. In Abbotsford, the celebration happens on Labour Day Weekend and is commemorated in the celebration of the Parkash Divas of the Guru Granth Sahib Ji. The parade in Abbotsford takes place near the Kalgidar Durbar.

Vaisakhi

Vaisakhi celebrations happen in both British Columbia and Ontario, with many including a Nagar Kirtan parade. In Ontario, the Vaisakhi celebrations are reported to get bigger and bigger in terms of festivities and attending populace every year. Many Sikh academies and institutes also participate in the Ontario parades, such as the Akal Academy Brampton. While the Nagar Kirtan in the Ontario Vaisakhi celebration starts at the Malton Gurudwara and ends at the Sikh Spiritual Centre, festivities go on until the Rexdale Gurudwara is reached, it is organized annually by the Ontario Gurdwara Committee. Nagar Kirtan parades also take place in Alberta. Both the cities of Calgary and Edmonton hold them around the May long weekend.[86]

Education

Punjabi is the native language of the Sikh faith; it is spoken commonly throughout both converts and Indo-Canadians. There is a large population of Sikh people in the city of Surrey; this has led to the availability of a course in the Punjabi language in the fifth grade using the British Columbia Punjabi Language Curriculum. In specific schools in the city of Abbotsford, the Punjabi language too is available as a course that can be taken following the fifth grade in elementary school levels.[87] For Abbotsford, however, when the curriculum was suggested to a more mainstream stray of schools, controversy was brought up, despite Punjabi being Abbotsford's second largest language. Many comments brought up were those who stated that only English and French should be taught in the district and that the costs to parents would be high, as always these comments were believed to be racially driven due to other secondary languages being taught for free in the district.[88]

Controversy

Kirpan cases

Various controversies have arisen involving the sacred Sikh dagger, the Kirpan. Most of these cases have taken place in the Canadian province of Quebec where the Sikh religion is incredibly minor to the dominant Abrahamic faiths, compared to other Canadian provinces.

Quebec Legislature

In February 2011, the Quebec National Assembly banned religious daggers, of which the kirpan was included. Upon the announcement, Canadian Sikh Liberal MP Navdeep Bains revealed his surprise and anger as he had worn the kirpan to the Supreme Court of Canada and the United States Congress without any trouble. The ban sparked a small debate amongst the Canadian Legislatures and news programs as well as backlash from the World Sikh Organization.[89] Following this was a vote that the kirpan be banned from all parliamentary buildings including the House of Commons of Canada. The vote happened in favour of the kirpan, despite fierce opposition from the Bloc Québécois.[90]

Montreal schools

In the 2006 Supreme Court of Canada decision of Multani v. Commission scolaire Marguerite‑Bourgeoys the court held that the banning of the kirpan in a school environment offended Canada's Charter of Rights and Freedoms, nor could the limitation be upheld under s. 1 of the Charter, as per R. v. Oakes. The issue started when a 12-year-old schoolboy dropped a 20 cm (8-inch) long kirpan in school. School staff and parents were very concerned, and the student was required to attend school under police supervision until the court decision[91] was reached. In September 2008, Montreal police announced that a 13-year-old student would be charged after he allegedly threatened another student with his kirpan. However, while he was declared guilty of threatening his schoolmates, he was granted an absolute discharge for the crime on April 15, 2009.[92]

Calgary Telus controversy

The World Sikh Organization representative Jasbeer Singh, who had involvement in the Multani Kirpan case, represented the WSO who had called on the Calgary Telus Convention Center for an apology on another kirpan case. In the Calgary stadium, a Gurdas Mann concert in 2009 had to be shut down after Sikh ticket holders had refused to remove their kirpans. Jasbeer was reportedly furious due to the case having occurred after it was proven that the kirpan was allowed to legally be worn in public areas due to the Multani v. Commission scolaire Marguerite-Bourgeoys case. Concert promoter Nirmal Dhaliwal revealed his intent on suing the centre due to the lack of revenue brought by the case.[93]

Turban cases

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police came under fire when they refused to let turbaned Canadian Sikh officers join their service. In doing so they had indefinitely banned all RCMP officers from wearing a turban, requiring them to wear the standard and traditional RCMP headdress. The ban was a result of the activism of a petition leader named Herman Bittner,[94] who maintained that he was preserving history rather than discriminating. The ban was lifted in 1990 and turbaned Sikh officers were permitted to join the RCMP.[95]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sikhism in Canada. |

References

- "Sikhs in Canada". World Sikh Organization of Canada. Retrieved 2019-11-03.

- "The Daily — 2011 National Household Survey: Immigration, place of birth, citizenship, ethnic origin, visible minorities, language and religion".

- "Sikhism | History, Doctrines, Practice, & Literature". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- April to be Sikh Heritage Month in Ontario - Times of India

- "Sikh Heritage Month Act, 2013". Legislative Assembly of Ontario. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Statistics, Canada. "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables Tabulation: Religion (108), Immigrant Status and Period of Immigration (11), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (8 May 2013). "Statistics Canada: 2011 National Household Survey Profile". Www12.statcan.gc.ca.

- "B.C. breaks records when it comes to religion and the lack thereof".

- "The South Asian Community in Canada".

- January 28, Douglas Todd Updated (10 March 2018). "Douglas Todd: Why Sikhs are so powerful in Canadian politics | Vancouver Sun". Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Dobie, Cayley. "Society carries tradition into the 21st century". New West Record.

- Baker, Rochelle (December 13, 2010). "Abbotsford's Gur Sikh Temple celebrates 100 years". Abbotsford Times. Retrieved 2 April 2011.(archived)

- "SIKHS OF OLIVER: Hardworking, Proud To Be Part Of BC Wine Country's Flourishing Community – DesiBuzz". Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Chronicle, Oliver. "Sikhs make world go round in Oliver | Oliver Chronicle". Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- City of, Mississauga. "2011CENSUS & NHS RESULTS MALTON PROFILE" (PDF). Mississauga.ca. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Ahmed-Ullah, Noreen. "How Brampton, a town in suburban Ontario, was dubbed a ghetto". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Sep 29, Dan McGarvey · CBC News · Posted; September 29, Dan McGarvey · CBC News · Posted. "Alberta's unexplored Sikh history documented for first time | CBC News". CBC.

- Oct 17, Israr Kasana · for CBC News · Posted; October 17, Israr Kasana · for CBC News · Posted. "OPINION | The dangers of self-ghettoization | CBC News". CBC.

- May 20, Anna McMillan · CBC News · Posted; May 21, Anna McMillan · CBC News · Posted. "Edmonton Sikh parade draws tens of thousands to Mill Woods neighbourhood | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "Sikhs Celebrate Hundred Years in Canada". Toronto Star. April 12, 1997. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- "Arrivals and Departures". The Colonies and India. 5 June 1897. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- "Komagata Maru". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- Century of Struggle and Success The Sikh Canadian Experience 13 November 2006

- "Gur Sikh Temple | CanadianSikhHeritage.ca". Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- "Paldi, BC, The Oldest Sikh Settlement In Canada Falls On Bad Days". darpanmagazine.com. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Block, Daniel. "The hard questions facing the poster boy of Canadian multiculturalism". The Caravan. Retrieved 2019-08-19.

- Block, Daniel. "The hard questions facing the poster boy of Canadian multiculturalism". The Caravan. Retrieved 2019-08-19.

- "Private Bukan Singh". Veterans Affairs Canada Virtual Memorial. 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- "Buckam Singh". The Sikh Museum. 2008. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- Mohindra, Rimple (June 4, 2011). "Indo-Canadians: The Depression & Immigration Issue". Abbotsford News. British Columbia, Abbotsford & Greater Vancouver Area.

- "South Asian voting rights granted in Canada due to Sikh demands". Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- "Sikh arrival in Ontario". Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- http://vahms.org/education/sikh-canadian-history/

- "Sikhism". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- "Sikh extremism spread fast in Canada". expressindia.com. 23 May 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- "Sikh extremism in Canada mushroomed very quickly". rediff.com. 23 May 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- Brown, Jim (22 November 2007). "The reign of terror is still there". Toronto Star. Toronto. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- http://www.sikhmuseum.com/bluestar/newsreports/pdfs/840606_3.pdf

- "Operation Blue Star 1984 Golden Temple Attack Sikhs".

- "Operation Blue Star 1984 Golden Temple Attack Sikhs". sikhmuseum.com.

- "Operation Blue Star 1984 Golden Temple Attack Sikhs".

- Goldman, Zachary K.; Rascoff, Samuel J. (26 April 2016). Global Intelligence Oversight: Governing Security in the Twenty-First Century. Oxford University Press. p. 177. ISBN 9780190458089.

- Hoffman, Bruce; Reinares, Fernando (28 October 2014). The Evolution of the Global Terrorist Threat: From 9/11 to Osama bin Laden's Death. Columbia University Press. p. 144. ISBN 9780231537438.

- "Man Convicted for 1985 Air India Bombing Now Free". Time. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- "Free. Fair. Fearless". Tehelka. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- "Man who won right for Sikhs to wear turbans in Canadian Legions dies". CBC News

- "Sikh Canadian History". Vancouver Asian Heritage Month Society.

- "Quebec Sikhs celebrate Vaisakhi with Canadian Forces".

- "Worldwide Sikh Diaspora approach UN Human Rights Commission regarding proposed hanging of Sikh political prisoner in India - Sikh Siyasat News (in English)". Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- "Hindustan Times - Archive News". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- "The Canadian Sikh Community Will Not Be Marginalized by Milewski and Kay – Global Sikh News". Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- CBC News. 28 March 2012 http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/story/2012/03/28/pol-sikh-parliament-hill-milewski.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Confronting Ignorance And Racism In Canada Like Racists On CKNW".

- "Sikh Cadets win their colours". Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- "Todd: A Vaisakhi primer on Hindu philosophical beliefs". Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- "Photos: Vancouver Vaisakhi parade, minus the politicians - Vancouver, Canada - Straight.com". Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- "Indo-Canadian Voice - 'Surrey Vaisakhi Parade to demonstrate support for Rajoana'". Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- "sikhchic.com - The Art and Culture of the Diaspora - How Three Sikh-Canadian Comics Found Global Fame".

- "Temple is the hub of the Sikh community". Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Rush, Curtis (16 May 2012). "Kirpan, Sikh ceremonial dagger, now allowed in Toronto courthouses". The Star. Toronto.

- http://sikhsangat.org/1699/tom-mulcair-responds-tells-india-he-wont-be-bullied-stands-firm-on-1984-statement/

- https://theprovince.com/news/Surrey+Sikhs+honour+victims+temple+tragedy/7048124/story.html

- "Indian Overseas Congress Approaches Akal Takht To Get Khalistan Insignias Removed From Gurdwaras In Canada And US".

- "Global News - Latest & Current News - Weather, Sports & Health News". Global News.

- Chase, Steven (November 8, 2012). "On Sikh separatism, Harper in India defends freedom of expression". The Globe and Mail.

- "Canadian Sikh Coalition Decries Abuse Of Democracy In The Punjab Arrest Of Activist Politicians Barapind And Bittu".

- "ontariosikhheritagemonth.ca – Ontario Sikh Heritage Month". ontariosikhheritagemonth.ca.

- "B.C. regiment that once forced out the Komagata Maru is now commanded by a Sikh". The Globe and Mail.

- Asia Samachar (8 May 2015). "Largest Khalsa Day parade outside India". Asia Samachar.

- "First Sikh soldier to guard Tomb of Unknown Soldier in Canada". hindustantimes.com/.

- "Sikh vs Sikh in upcoming Canada polls". The Economic Times.

- "Full list of Justin Trudeau's cabinet". 5 November 2015.

- Daniel Dale (11 March 2016). "Trudeau fields Trump questions from American students". thestar.com.

- Sikh24 Editors (5 November 2015). "Amritdhari Sikhs Hold Cabinet Positions in a Country for First Time Since Sikh Kingdom". Sikh24.com.

- Firstpost (3 November 2015). "Oye hoye! Punjabi is now the third language in Parliament of Canada". Firstpost.

- Jagdeesh Mann. "Opinion: Sacrilege in Punjab, aftershocks in Canada". www.vancouversun.com.

- "Komagata Maru: Justin Trudeau to apologize for 1914 incident". 11 April 2016.

- "Jagmeet Singh becomes first Sikh politician to lead major Canadian party". Hindustan Times.

- Zimonjic, Peter (1 October 2017). "Meet Jagmeet Singh: New leader of federal NDP". CBC News. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "Abbotsford’s Sikh numbers nearly double over last decade: Statistics Canada" (Archive). Vancouver Desi. May 8, 2013. Retrieved on November 16, 2014.

- Mills, Kevin. "Abbotsford's Sikh population has doubled in the past 10 years" (Archive). Abbotsford News. May 14, 2013. Retrieved on November 16, 2014.

- "Abbotsford’s Gur Sikh Temple celebrates its 100th anniversary." Government of Canada. August 28, 2011. Retrieved on November 16, 2014.

- "Budh Singh and Kashmir Kaur Dhahan" (Archive). Carleton University. Retrieved on April 13, 2015.

- "National Household Survey (NHS) Profile, 2011".

- "e-Veritas » Blog Archive » Cadets All Over the Place on Remembrance Day".

- "Ontario Sikhs take to the streets". SikhNet.

- stationary

- Vikki Hopes. "Abbotsford school district considers expansion of Punjabi classes". Abbotsford News.

- "Article18: Canada - Sikhs Upset After Quebec National Assembly Bans Religious Daggers; Controversy Reignites Multiculturalism Debate - ReligiousLiberty.TV - Celebrating Liberty of Conscience". ReligiousLiberty.TV - Celebrating Liberty of Conscience.

- "Parliament to 'accept and embrace' wearing of kirpan, sergeant-at-arms explains". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. 3 June 2011.

- "Bulletin of March 3, 2006" (in French). Supreme Court of Canada / Cour Suprême du Canada. March 3, 2006.

- "Sikh boy guilty of assault with hairpin". CBC News. April 15, 2009. Retrieved 2011-02-10.

- Tarina White (August 5, 2009). "Sikhs' knives out over kirpan controversy". Owen Sound Sun-Times.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1990/03/16/canada-says-sikh-mounties-can-wear-turbans/c5fa5ffe-c7e6-42c8-a1dd-eb68426b9938/

- "CBC Archives". CBC. Retrieved 6 January 2019.