Canadian Grand Prix

The Canadian Grand Prix (French: Grand Prix du Canada) is an annual auto race held in Canada since 1961.[1] It has been part of the Formula One World Championship since 1967. It was first staged at Mosport Park in Bowmanville, Ontario, as a sports car event, before alternating between Mosport and Circuit Mont-Tremblant, Quebec, after Formula One took over the event. After 1971, safety concerns led to the Grand Prix moving permanently to Mosport. In 1978, after similar safety concerns with Mosport, the Canadian Grand Prix moved to its current home at Circuit Gilles Villeneuve on Notre Dame Island in Montreal.

| Circuit Gilles Villeneuve (1996–present) | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 56 |

| First held | 1961 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Circuit length | 4.361 km (2.709 mi) |

| Race length | 305.270 km (189.694 mi) |

| Laps | 70 |

| Last race (2019) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

In 2005, the Canadian Grand Prix was the most watched Formula One GP in the world. The race was also the third most watched sporting event worldwide, behind the first place Super Bowl XXXIX and the UEFA Champions League Final.[2]

Preceding the qualifying session in 2014, the Grand Prix organizers announced they had agreed to a 10-year extension to keep the Canadian Grand Prix at Circuit Gilles Villeneuve through 2024.[3] The 2020 event was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada.[4]

History

Origins

The early Canadian Grand Prix was one of the premier events of the new Canadian Sports Car Championship, a series which had been created alongside the Canadian Grand Prix at Mosport Park near Toronto in 1961. Mosport Park (which is still in its original layout configuration) was a spectacular and challenging circuit which had many ups and downs; the circuit was popular with drivers. Several international sports car as well as Formula One drivers participated in the event. For the first five years, the event would be won by drivers with either prior Formula One experience, or would enter the championship after winning the Canadian Grand Prix. In 1966 the Canadian-American Challenge Cup ran the event, with American Mark Donohue winning.[1] Formula One took over the following year, although the CSCC and Can-Am series continued to compete at Mosport in their own events.

Formula One

Mosport Park and Mont-Tremblant

The event was run as part of the Formula One world championship first in 1967; Mosport Park was selected as the venue for the event. The Ontario circuit alternated with the Circuit Mont-Tremblant in Quebec, where the Canadian Grand Prix was held in 1968 and 1970. Mont-Tremblant, located 1 1/2 hours northwest of Montreal was much like Mosport Park in that it was a spectacular circuit which had much elevation change and was very challenging. The first championship race was held between the German and Italian rounds in October; it was won by Jack Brabham with his New Zealander teammate Denny Hulme completing a Brabham 1–2.

The 1968 event, which was moved to late September so it could be paired with the United States Grand Prix at Watkins Glen saw the unlucky New Zealander Chris Amon lead from the start until 17 laps from the end of the 90 lap distance when his gearbox broke; the McLaren team finished 1–2 with Amon's countrymen Hulme and Bruce McLaren taking top honours. The 1969 event at Mosport Park saw Briton Jackie Stewart climb up from 4th to take the lead, but Jacky Ickx was coming up fast, and Stewart and Ickx battled until lap 33, when they came to lap privateer Al Pease for the fourth time, Ickx attempted to pass Stewart, and the two cars collided. Stewart was unable to get his Matra going, but Ickx did get his Brabham going, and held onto the lead until the checkered flag. An angry Stewart complained to his boss Ken Tyrrell about Pease, who complained to the organizers. The 48-year-old Pease was then given the black disqualification flag after completing less than half the number of laps the leaders had completed in an almost embarrassingly outdated Eagle-Climax, and became the only driver in F1 history ever to be disqualified for being too slow. The 1970 event saw Ickx win again with his Swiss teammate Clay Regazzoni making the result a Ferrari 1–2. But the Mont-Tremblant circuit was not used again for Formula One because of safety concerns regarding the bitter winters seriously affecting the track surface and a dispute with the local racing authorities there in 1972. The alternating of the race stopped and Mosport solely continued to hold the Canadian Grand Prix from 1971.

The 1971 event saw Mosport Park flooded with rain; the main event was delayed after a fatal accident at a Formula Ford support race and by the time it started, it was raining heavily. Jackie Stewart took victory easily in a Tyrrell from Swede Ronnie Peterson in a March. 1972 saw Mosport upgraded with new safety features, and Stewart won again. 1973 was an interesting event; like the race 2 years previous it was a rain-soaked event. Austrian new-boy Niki Lauda in a BRM took the lead from Peterson in a Lotus on Lap 3, Lauda led until the 20th lap when he came to change tires; there was considerable confusion after François Cevert and Jody Scheckter collided on Lap 33 leading to a bungled pace car interlude after which things became very confused as the pace car failed to pick up the leader and allowed those ahead to gain almost a lap. All this meant that Briton Jackie Oliver ended up in the lead with American Peter Revson second and Frenchman Jean-Pierre Beltoise third. Of these three Revson had the most competitive car and so eventually moved into the lead and led all the way to the flag while Peterson's Brazilian teammate Emerson Fittipaldi charged to try to make up for lost ground and overtook Oliver and Beltoise in the closing laps to grab second. For hours after the race confusion reigned but eventually it was confirmed that Revson was the winner- thanks to a lucky break when the pace car came out. The 1974 event saw Fittipaldi win while his championship rivals Clay Regazzoni finished 2nd and Jody Scheckter crashed heavily after a brake failure on his Tyrrell. There was no 1975 event, and the 1976 event was one where Briton James Hunt found out that his 9 points from Brands Hatch were taken away and he was disqualified; Hunt won the Canadian Grand Prix event that year, driving furiously throughout the race.

1977 was the race where French-Canadian Gilles Villeneuve made his debut for Ferrari. But concerns about the bumpy Mosport Park's safety arose when Briton Ian Ashley had a horrendous accident while cresting a bumpy rise. Ashley's Hesketh flipped over the Armco guardrails and went into a television tower. The German-born Englishman was seriously injured and safety operations to rescue him were inefficient and time-consuming; and the lack of safety at Mosport was underlined when Jochen Mass lost control of his McLaren and hit a guardrail that virtually flattened upon impact. Jody Scheckter won this race in his Wolf, but with safety not being good enough for Formula One at the rough and very fast Mosport Park circuit, a new proposal was brought forward: a track called the Circuit Île Notre Dame; a man-made island in the middle of the St. Lawrence sea-way that was the site of the famous Expo '67; specific roads on the island were combined and modified, and then pit facilities were built to make a temporary race track. The Canadian Grand Prix was first held there in 1978 and it has been held there ever since, with the exception of two separate years when the event was cancelled.

Montreal

The first winner in Montreal was Quebec native Villeneuve, driving a Ferrari. 1979 saw circuit layout modifications to make it faster, and Australian Alan Jones win, and he then won the 1980 race and the Drivers' Championship that year. 1980 also saw a big startline pile-up with involved Jones's Brazilian championship rival Nelson Piquet after he and Jones collided going into the very fast Droit du Casino corner. Piquet jumped into his spare car with a more powerful qualifying engine; but the engine blew up and Piquet retired from the race. Frenchman Jean-Pierre Jabouille's season and F1 racing career came to an end when he crashed his Renault head-on into a tire wall. He had badly broken legs; it took the tall Frenchman months to recover. 1981 saw a rain-soaked event in which near end of the race, Villeneuve demonstrated his car control skill when the front wing of his Ferrari was askew from a crash and he drove on to third place with the car in this condition. Frenchman Jacques Laffite took what was to be his last F1 victory, followed by Briton John Watson and Villeneuve.

Villeneuve was killed in 1982 on his final qualifying lap for the Belgian Grand Prix. A few weeks after his death, the race course in Montreal was renamed Circuit Gilles Villeneuve after him. Gilles Villeneuve was one of the first people inducted into the Canadian Motorsport Hall of Fame, and is so far the only Canadian winner of the Formula One Canadian Grand Prix. The 1982 Canadian Grand Prix was a tragic event, in the shadow of the death of Villeneuve a month earlier. It saw another accident when Villeneuve's teammate Didier Pironi stalled at the front of the grid. First, Raul Boesel struck a glancing blow to the stationary vehicle, and then Riccardo Paletti crashed directly into the rear of Pironi's Ferrari at over 180 km/h (110 mph). Pironi and F1 doctor Sid Watkins came to Paletti's aid to try to extract him from his car, which briefly caught fire. After a half-hour, the 23-year-old Paletti was extracted and flown to a nearby hospital, where he succumbed to his injuries. Nelson Piquet won the race in his Brabham. 1982 was also significant in that the race was moved from October to June with the event happening in early June ever since. 1983 saw Frenchman René Arnoux win his first race as a Ferrari driver, and the following year Piquet won again in a BMW-powered Brabham. 1985 saw Ferrari finish 1–2 with Italian Michele Alboreto and Swede Stefan Johansson taking top honours from Frenchman Alain Prost, while Lotus gained their final ever lock-out of the front row when Elio de Angelis and Ayrton Senna started 1–2. 1986 was a competitive race. Finn Keke Rosberg in a McLaren charged through the field, caught and then passed British leader Nigel Mansell. But Rosberg, like the other front runners, encountered problems, benefiting Mansell who won the race. In 1987, the race was not held due to sponsorship dispute between two local breweries, Labatt and Molson.[5] During the break the track was modified, and starting line moved to its current position.

1988 saw Brazilian Ayrton Senna take victory in the all-conquering McLaren MP4/4 with its Honda turbo engine, and the following year he so very nearly won again, but the Honda engine in his McLaren failed and Belgian Thierry Boutsen took victory, which was the first in his F1 career. 1990, like the year before, was a rain-soaked event, and it saw a number of accidents; Senna came out to win again. 1991 saw a dramatic finale in which Nigel Mansell's Williams failed on the very last lap only a few corners from the finish line; Nelson Piquet took his 23rd and final F1 victory in a Benetton. Austrian Gerhard Berger won the 1992 event after the dominant Mansell spun off after a collision with Berger's teammate Senna. Alain Prost won the 1993 event while fending off a spirited drive from Senna, and in response to the Imola tragedies, the 1994 event saw the very fast Droit du Casino curve being turned into a chicane. German Michael Schumacher won this event. Ferrari's Jean Alesi won the 1995 edition, which occurred on his 31st birthday and which would be the only win of his career. Alesi had inherited the lead when Michael Schumacher pitted with electrical problems and Damon Hill's hydraulics failed. The victory was a popular one for Alesi, particularly after several unrewarded drives the year before, namely in Italy. Alesi's win at Montreal was voted the most popular race victory of the season by many, as it was the number 27 Ferrari—once belonging to the famous Gilles Villeneuve at his much loved home Grand Prix. Schumacher gave Alesi a lift back to the pits after Alesi's car ran out of fuel just before the Pits Hairpin.

The Canadian Grand Prix race had grown in importance around this time; the demise of Grands Prix in Detroit, Phoenix and Mexico City meant that it had been the only North American Grand Prix round since 1993 and would continue to be the only round in North America up until 1999, and again from 2008 to 2011 after yet another demise of the United States Grand Prix, this time at Indianapolis. It was also one of two races in the entire Americas, the other being the Brazilian Grand Prix, although the Argentine Grand Prix had returned for 4 brief years from 1995 to 1998. The 1996 race saw the Casino corner removed and the layout changed; the run from the hairpin at the bottom of the circuit was turned into a straight. Briton Damon Hill won this event, and the 1997 race was stopped early due to a crash involving Olivier Panis. He was sidelined for nine races and some see it as a turning point in the career of the 1996 Monaco Grand Prix winner. The races from 1997 to 2004 (except 1999 and 2001) saw a romp of Michael Schumacher victories, all in a Ferrari. 1999 saw Finn Mika Häkkinen win, and in 2001, there was the first sibling 1–2 finish in the history of Formula 1, as Ralf and Michael Schumacher topped the podium. The Schumacher brothers would finish 1–2 in the 2003 edition as well, 2001 was also noted for Jean Alesi achieving Prost's best finish of the season; he celebrated his fifth place by doing several donuts in his vehicle, and throwing his helmet into the crowd. The 2007 race was the site of rookie Lewis Hamilton's first win. On lap 67, Takuma Sato overtook McLaren-Mercedes's Fernando Alonso, to cheers around the circuit, just after overtaking Ralf Schumacher and having overtaken Ferrari's Kimi Räikkönen earlier in the race.[6] The race saw Sato move from the middle of the grid to the back of the pack and to a high of fifth before a pit-stop error caused him to move back to eleventh. Sato fought up 5 places in the field in the last 15 laps to finish sixth. Sato was voted "Driver of the Day" on the ITV website over Lewis Hamilton's first win. The race also saw an atrocious crash involving Robert Kubica (who went on to win the race the following season, resulting to be his only one in F1). The 2011 Canadian Grand Prix became the longest ever Formula One race to date; rainstorms delayed the race for hours; but when it got going again Briton Jenson Button stormed through the field from last place after the restart on lap 41 and caught German leader Sebastian Vettel; whom he forced into making a mistake, passed the Red Bull driver and the Briton took victory, in what he described as "my best ever race".[7] The 2013 Canadian Grand Prix saw Vettel dominate in his Red Bull, but it was also to see the first Formula One-related fatality in 12 years. Thirty-eight-year-old track marshal Mark Robinson was run over by a recovery vehicle, and the accident happened while marshals were removing the Sauber of Esteban Gutiérrez after the Mexican had spun off during the closing stages of the race. Robinson died later in hospital and became the first track-side death in Formula One since that of marshal Graham Beveridge at the 2001 Australian Grand Prix.

Wildlife

In the weeks leading up the Grand Prix, city officials trap as many groundhogs as they can in and around the race course, and transport the animals to nearby Île Ste-Helene.[8] Nonetheless, in 1990, Alessandro Nannini struck a gopher on the track which damaged his tire. In 2007, a groundhog disrupted the practice session of Ralf Schumacher. On race day itself, Anthony Davidson had been running in third until he struck a groundhog, initially thought to be a beaver, which forced him to pit and repair the damage to his front wing. In 2008, a groundhog crossed the track at the hairpin in the 2nd practice session but luckily did not disrupt the session. In 2018, Romain Grosjean struck a groundhog in the 2nd practice session on the approach to turn 13, damaging his front wing.

Wall of Champions

The final corner of Circuit Gilles Villeneuve became well known for crashes involving former World Champions. In 1999, Damon Hill, Michael Schumacher and Jacques Villeneuve all crashed into the same wall which had the slogan Bienvenue au Québec (Welcome to Quebec) on it. The wall became ironically known as "Wall of Champions". The wall also was involved in a crash with Ricardo Zonta, who was, at the time, the reigning FIA GT sports car champion. In recent years, Formula One 2016 World Champion Nico Rosberg, CART Champion Juan Pablo Montoya, Formula Renault 3.5 Champion Carlos Sainz Jr. and 2009 Formula One World Champion Jenson Button have also fallen victim to the wall.[9] In 2011 Friday practice the wall claimed 4-time F1 Champion Sebastian Vettel.[10] During Q2 in 2019, the wall claimed another former Formula Renault 3.5 champion, Kevin Magnussen, though he escaped serious injury.[11]

Before the wall was named it also claimed victims such as 1992 World Sportscar Champion and long-time F1 driver Derek Warwick who spectacularly crashed his Arrows-Megatron during qualifying for the 1988 Canadian Grand Prix.[12]

2009 hiatus

On 7 October 2008, the Canadian Grand Prix was dropped from the 2009 Formula One calendar, which left the Montreal race off the list for the first time since 1987.[13]

Since the United States Grand Prix was dropped after 2007, this meant that in 2009 no Formula One race was held in North America for the first time since 1958.[14] (The American Indianapolis 500 formed part of the FIA World Drivers' Championship from 1950 to 1960, but was not run to Formula One regulations and only very rarely entered by regular championship competitors.)

During the Australian Grand Prix, reports surfaced that the Canadian Grand Prix could return during the 2009 season in the event that the race circuit in Abu Dhabi was not ready in time.[15] On 26 April 2009, Speed reported Bernie Ecclestone as saying the FIA was negotiating a return of the Canadian Grand Prix for the 2010 season, provided upgrades to the circuit were completed.

On 29 August 2009, the BBC reported the provisional schedule for the 2010 season, which had both the Canadian and British Grand Prix marked down as "provisional". The Canadian GP was scheduled for 6 June.[16] The 2010 Canadian Grand Prix was eventually run in Montreal on 13 June 2010.[17]

On 27 November 2009, Quebec's officials and Canadian Grand Prix organizers announced they had reached a settlement with Formula One Administration and signed a new five-year contract spanning the 2010–2014 seasons.[18] Under the five-year agreement, the government pays 15 million Canadian dollars a year to host the race, much less than the 35 million a year Ecclestone initially asked for.[19]

Official names

- 1961–1966: Pepsi Cola Canadian Grand Prix

- 1967, 1969 Player's Grand Prix of Canada[20][21]

- 1968: Player's Grand Prix[22]

- 1970–1971: Player's Grand Prix Canada[23][24]

- 1972–1974, 1976–1977: Labatt's Grand Prix of Canada[25][26][27][28][29][30]

- 1978, 2004–2008, 2010–2017: Grand Prix du Canada (no official sponsor)[31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44]

- 1979: Grand Prix du Canada Labatt[45]

- 1980–1986: Grand Prix Labatt du Canada[46][47][48][49][50][51][52]

- 1988: Molson Grand Prix du Canada[53]

- 1989–1996: Grand Prix Molson du Canada[54][55][56][57][58][59][60]

- 1997–1998: Grand Prix Player's du Canada[61][62]

- 1999–2003: Grand Prix Air Canada[63][64][65][66][67]

- 2018: Grand Prix Heineken du Canada[68][69]

- 2019: Pirelli Grand Prix du Canada[70][71]

Because of tobacco legislation which prohibited further such sponsorship, new venues, and a maximum of 17 races on the schedule, the Canadian Grand Prix was initially removed from the 2004 F1 schedule. However, Canadian officials were able to raise enough money to keep a Grand Prix race, with the FIA allowing expansion to an 18-race schedule.[72][73]

Winners of the Canadian Grand Prix

Repeat winners (drivers)

Drivers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| Wins | Driver | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | 1994, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2004 | |

| 2007, 2010, 2012, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2019 | ||

| 3 | 1982, 1984, 1991 | |

| 2 | 1963, 1964 | |

| 1969, 1970 | ||

| 1971, 1972 | ||

| 1979, 1980 | ||

| 1988, 1990 | ||

| 2013, 2018 |

Repeat winners (constructors)

Teams in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| Wins | Constructor | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 14 | 1963, 1964, 1970, 1978, 1983, 1985, 1995, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2018 | |

| 13 | 1968, 1973, 1974, 1976, 1988, 1990, 1992, 1999, 2005, 2007, 2010, 2011, 2012 | |

| 7 | 1979, 1980, 1986, 1989, 1993, 1996, 2001 | |

| 4 | 1967, 1969, 1982, 1984 | |

| 2015, 2016, 2017, 2019 | ||

| 2 | 1961, 1962 | |

| 1971, 1972 | ||

| 1991, 1994 | ||

| 2013, 2014 |

Repeat winners (engine manufacturers)

Manufacturers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| Wins | Manufacturer | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 14 | 1963, 1964, 1970, 1978, 1983, 1985, 1995, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2018 | |

| 12 | 1968, 1969, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1979, 1980, 1991, 1994 | |

| 10 | 1999, 2005, 2007, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2019 | |

| 6 | 1989, 1993, 1996, 2006, 2013, 2014 | |

| 4 | 1986, 1988, 1990, 1992 | |

| 1982, 1984, 2001, 2008 | ||

| 2 | 1961, 1962 | |

| 1965, 1966 |

* Built by ![]()

** Between 1999-2005 built by ![]()

Year by year

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

Previous circuits used

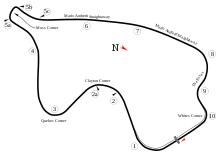

Mosport Park (1967,1969,1971-1974,1976-1977)

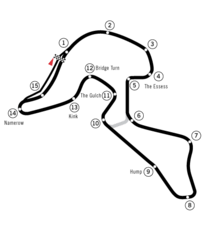

Mosport Park (1967,1969,1971-1974,1976-1977) Circuit Mont-Tremblant (1968,1970)

Circuit Mont-Tremblant (1968,1970).svg.png) Circuit Île Notre Dame/Gilles Villeneuve (1978-1986)

Circuit Île Notre Dame/Gilles Villeneuve (1978-1986).svg.png) Circuit Gilles Villeneuve (1988-1993)

Circuit Gilles Villeneuve (1988-1993).svg.png) Circuit Gilles Villeneuve (1994-1995)

Circuit Gilles Villeneuve (1994-1995).svg.png) Circuit Gilles Villeneuve (1996-2001)

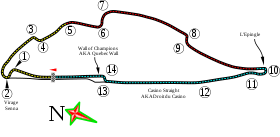

Circuit Gilles Villeneuve (1996-2001)

References

- "Canadian Grand Prix". Motor Racing Circuits Database. Archived from the original on 5 November 2007. Retrieved 14 January 2008.

- Most watched TV sporting events of 2005 Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine – A special report from Initiative

- – Motor racing-Canadian GP organizers announce 10-year extension

- "Montreal Formula 1 cancelled due to COVID-19". CTV Montreal News. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Remember When...a GP was last cancelled?". Autosport. Vol. 203 no. 8. Haymarket Publications. 24 February 2011. p. 11.

The 1987 Canadian GP was canned because of a legal case following the promoter signing a sponsorship deal with Molson when rival company Labatt claimed to have first-refusal rights.

- Benson, Andrew (10 June 2007). "Hamilton wins Canadian GP". BBC Sports. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- "Classic F1 - Jenson Button wins epic 2011 Canadian GP". BBC Sport. 12 June 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- "'Beaver' gets all the blame". Vancouver Sun. Canada.com. 12 June 2007. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- "The wall of champions - Youtube". F1 Martin. 25 June 2014.

- Benson, Andrew (10 June 2011). "BBC Sport – Fernando Alonso sets the pace for Ferrari in a thrilling Canada practice". BBC News. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- Sam Hall (8 June 2019). "Haas F1 driver Kevin Magnussen meets the 'Wall of Champions' in Canada". Autoweek. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- FIA F1 Review 1988 – Canada

- "Canada missing from Formula 1 calendar in 2009". grandprix.com. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- "Canada GP organizers surprised by FIA decision". Pitpass.com. 8 October 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- Canadian Press, "Montreal's mayor responds to reports about F1 race returning", 29 March 2009

- (in French) RDS, La F1 à Montréal le 6 juin (accessed 30 August 2009)

- Circuit Gilles Villeneuve site Archived 14 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Canada returns to F1 championship – f1-live.com, 27 November 2009

- Montreal Grand Prix Is Back On for 2010 – The New York Times, 27 November 2009

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.]

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Formula 1 Grand Prix Heineken du Canada 2018". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Limited. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- "Programme covers". www.progcovers.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Formula 1 Pirelli Grand Prix du Canada 2019". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Limited. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Canadian Grand Prix off 2004 schedule". CBC.ca. 7 August 2003.

- Henry, Alan (22 August 2003). "Last-ditch push to save Canadian Grand Prix". TheGuardian.com. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canadian Grand Prix. |