Peoria, Illinois

Peoria (/piˈɔːriə/ pee-OR-ee-ə) is the county seat of Peoria County, Illinois,[4] and the largest city on the Illinois River. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 115,007.[5] It is the principal city of the Peoria Metropolitan Area in Central Illinois, consisting of the counties of Marshall, Peoria, Stark, Tazewell, and Woodford, which had a population of 373,590 in 2011.

Peoria, Illinois | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Peoria | |

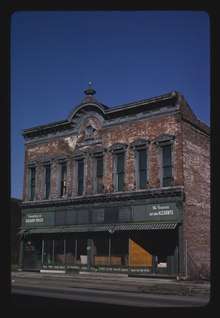

Peoria City Hall | |

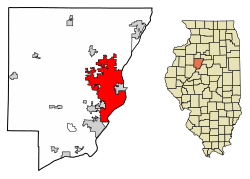

Location of Peoria in Peoria County, Illinois. | |

.svg.png) Location of Illinois in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 40°43′15″N 89°36′34″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Peoria |

| Settled | 1691 |

| Incorporated Town | 1835 |

| Incorporated City | 1845 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Jim Ardis |

| • City Manager | Patrick Urich |

| • City Clerk | Beth Ball |

| • City Treasurer | Patrick Nichting |

| Area | |

| • City | 50.40 sq mi (130.54 km2) |

| • Land | 48.00 sq mi (124.32 km2) |

| • Water | 2.40 sq mi (6.22 km2) |

| Elevation | 509 ft (155 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • City | 115,007 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 110,417 |

| • Density | 2,300.31/sq mi (888.15/km2) |

| • Metro | 373,590 |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 29 total ZIP codes:

|

| Area code(s) | 309 |

| FIPS code | 17-59000 |

| Website | www |

Established in 1691 by the French explorer Henri de Tonti, Peoria was later labeled by the Peoria Historical Society to be the oldest European settlement in Illinois.[6] Originally known as Fort Clark, it received its current name when the County of Peoria organized in 1825. The city was named after the Peoria tribe, a member of the Illinois Confederation. On October 16, 1854, Abraham Lincoln made his Peoria speech against the Kansas-Nebraska Act.[7][8]

A major port on the Illinois River, Peoria is a trading and shipping center for a large agricultural area that produces maize, soybeans, and livestock. Although the economy is well diversified, the city's traditional manufacturing industries remain important and produce earthmoving equipment, metal products, lawn-care equipment, labels, steel towers, farm equipment, building materials, steel, wire, and chemicals.[9] Until 2018, Peoria was the global and national headquarters for heavy equipment and engine manufacturer Caterpillar Inc., one of the 30 companies composing the Dow Jones Industrial Average, and listed on the Fortune 100; in the latter year, the company relocated its headquarters to Deerfield, Illinois.[10][11]

The city is associated with the phrase "Will it play in Peoria?", which originated from the vaudeville era and was popularized by Groucho Marx.[12] Museums in the city include the Pettengill-Morron House, the John C. Flanagan House, and the Peoria Riverfront Museum.

History

Peoria is the oldest European settlement in Illinois, as explorers first ventured up the Illinois River from the Mississippi. The lands that eventually would become Peoria were first settled by Europeans in 1680, when French explorers René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and Henri de Tonti constructed Fort Crevecoeur.[6] This fort would later burn to the ground, and in 1813, Fort Clark, Illinois was built. When the County of Peoria was organized in 1825, Fort Clark was officially named Peoria.[13]

Peoria was named after the Peoria tribe, a member of the Illinois Confederation. The original meaning of the word is uncertain.[14] A 21st-century proposal suggests a derivation from a Proto-Algonquian word meaning "to dream with the help of a manitou."[15]

Peoria was incorporated as a village on March 11, 1835. The city did not have a mayor, though they had a village president, Rudolphus Rouse, who served from 1835 to 1836. The first Chief of Police, John B Lishk, was appointed in 1837. The city was incorporated on April 21, 1845. This was the end of a village president and the start of the mayoral system, with the first mayor being William Hale.

Peoria, Arizona, a suburb of Phoenix, was named after Peoria, Illinois because the two men who founded it in 1890 − Joseph B. Greenhut and Deloss S. Brown − wished to name it after their hometown.[16]

For much of the twentieth century, a red-light district of brothels and bars known as the Merry-Go-Round was part of Peoria.[17] Betty Friedan recalled driving through the neighborhood on dares during her high school years.

Richard Pryor got his start as a performer on North Washington Street in the early 1960s.[18]

Topography

According to the 2010 census, Peoria has a total area of 50.23 square miles (130.10 km2), of which 48.01 square miles (124.35 km2) (or 95.58%) is land and 2.22 square miles (5.75 km2) (or 4.42%) is water.[19]

Climate

Peoria has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa), with cold, snowy winters, and hot, humid summers. Monthly daily mean temperatures range from 22.5 °F (−5.3 °C) to 75.2 °F (24.0 °C). Snowfall is common in the winter, averaging 26.3 inches (67 cm), but this figure varies considerably from year to year. Precipitation, averaging 36 inches (914 mm), peaks in the spring and summer, and is the lowest in winter. Extremes have ranged from −27 °F (−33 °C) in January 1884 to 113 °F (45 °C) in July 1936.[20]

| Climate data for Peoria, Illinois (Peoria Int'l), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1883-present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

74 (23) |

87 (31) |

92 (33) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

113 (45) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

93 (34) |

81 (27) |

71 (22) |

113 (45) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 53 (12) |

58 (14) |

73 (23) |

83 (28) |

88 (31) |

94 (34) |

97 (36) |

95 (35) |

92 (33) |

83 (28) |

70 (21) |

58 (14) |

98 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 32.8 (0.4) |

37.7 (3.2) |

50.3 (10.2) |

63.0 (17.2) |

73.2 (22.9) |

82.2 (27.9) |

85.6 (29.8) |

83.8 (28.8) |

77.0 (25.0) |

64.5 (18.1) |

50.3 (10.2) |

36.1 (2.3) |

61.5 (16.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 24.9 (−3.9) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

40.6 (4.8) |

52.3 (11.3) |

62.4 (16.9) |

71.8 (22.1) |

75.5 (24.2) |

73.8 (23.2) |

66.1 (18.9) |

54.0 (12.2) |

41.6 (5.3) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

51.9 (11.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 17.0 (−8.3) |

21.2 (−6.0) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

41.7 (5.4) |

51.6 (10.9) |

61.4 (16.3) |

65.5 (18.6) |

63.7 (17.6) |

55.2 (12.9) |

43.5 (6.4) |

32.9 (0.5) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

42.2 (5.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −7 (−22) |

−2 (−19) |

11 (−12) |

26 (−3) |

36 (2) |

48 (9) |

54 (12) |

51 (11) |

39 (4) |

28 (−2) |

14 (−10) |

−1 (−18) |

−11 (−24) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −27 (−33) |

−26 (−32) |

−10 (−23) |

14 (−10) |

25 (−4) |

39 (4) |

46 (8) |

41 (5) |

26 (−3) |

7 (−14) |

−2 (−19) |

−24 (−31) |

−27 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.78 (45) |

1.79 (45) |

2.80 (71) |

3.63 (92) |

4.33 (110) |

3.53 (90) |

3.85 (98) |

3.24 (82) |

3.15 (80) |

2.84 (72) |

3.13 (80) |

2.42 (61) |

36.49 (927) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.9 (18) |

6.2 (16) |

2.7 (6.9) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

trace | 1.1 (2.8) |

7.1 (18) |

24.6 (62) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.2 | 8.4 | 10.4 | 11.4 | 11.8 | 10.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 8.1 | 9.2 | 9.6 | 10.1 | 116.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 5.8 | 4.7 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 5.5 | 19.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73.9 | 73.8 | 70.5 | 64.7 | 66.2 | 67.3 | 71.7 | 73.7 | 72.7 | 70.4 | 74.5 | 78.0 | 71.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 147.4 | 155.6 | 187.9 | 222.8 | 272.6 | 306.9 | 310.1 | 279.3 | 233.2 | 204.2 | 127.9 | 118.7 | 2,566.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 53 | 53 | 50 | 57 | 63 | 69 | 70 | 68 | 66 | 62 | 47 | 44 | 60 |

| Source: NOAA (sun and relative humidity 1961–1990)[21][22][23] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

The city of Peoria is home to a United States courthouse and the Peoria Civic Center (which includes Carver Arena). The world headquarters for Caterpillar Inc. was based in Peoria for over 110 years until announcing their move to Deerfield, Illinois in late 2017.[24] Medicine has become a major part of Peoria's economy. In addition to three major hospitals, the USDA's National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, formerly called the USDA Northern Regional Research Lab, is located in Peoria. This is one of the labs where mass production of penicillin was developed.[25][26]

Grandview Drive, which Theodore Roosevelt purportedly called the "world's most beautiful drive" during a 1910 visit,[27] runs through Peoria and Peoria Heights. In addition to Grandview Drive, the Peoria Park District contains 9,000 acres (36 km2) of parks and trails. The Illinois River Bluff Trail connects four Peoria Park District parks: Camp Wokanda, Robinson Park, Green Valley Camp, and Detweiller Park, and the Rock Island Greenway (13 miles) connects the State of Illinois Rock Island trail traveling north to Toulon, IL and also connects southeast to East Peoria, IL and to the Morton Community Bikeway. Other parks include the Forest Park Nature Center, which features seven miles of hiking trails through prairie openings and forested woodlands, Glen Oak Park, and Bradley Park, which features Frisbee golf as well as a dog park. Peoria has five public golf courses as well as several private and semi-private golf courses. The Peoria Park District, the first and still largest park district in Illinois, was the 2001 Winner of the National Gold Medal Award for Excellence in Parks and Recreation for Class II Parks.[28]

Culture

Museums in Peoria include the Pettengill-Morron House, the John C Flanagan House of the Peoria Historical Society, and the Wheels o' Time Museum. The Museum Block, opened on October 12, 2012, houses the Peoria Riverfront Museum, a planetarium, and the Caterpillar World Visitors Center.[29]

The Peoria Art Guild hosts the Annual Art Fair, which is continually rated as one of the 100 top art fairs in the nation.[30]

Three cultural institutions are located in Glen Oak Park. The Peoria Zoo, formerly Glen Oak Zoo, was expanded and refurbished in recent years. Finished in 2009, the new zoo improvements more than triple the size of the zoo and feature a major African safari exhibit.[31] Luthy Garden, established in 1951, encompasses five acres and offers over a dozen theme gardens and a Conservatory. The Peoria PlayHouse Children's Museum opened in June 2015 in the Glen Oak Pavilion.

The Steamboat Classic, held every summer, is the world's largest four-mile (6 km) running race and draws international runners.[32]

The Peoria Santa Claus Parade, which started in 1888, is the oldest running holiday parade in the United States.[33]

Peoria's sister cities include Friedrichshafen, Germany; Benxi, China; Clonmel, Ireland; and Aitou, Lebanon.[34][35]

Performing arts

The Peoria Symphony Orchestra is the 14th oldest in the nation. Peoria is also home to the Peoria Municipal Band, the Peoria Area Civic Chorale, the Youth Music Illinois (formerly known as Central Illinois Youth Symphony), and the Peoria Ballet. Several community and professional theaters have their home in and around Peoria, including the Peoria Players, which is the fourth-oldest community theater in the nation and the oldest in Illinois.[36] Corn Stock Theatre is another community theater company in Peoria, and is the only outdoor theater company in Central Illinois.[37]

Peoria has hosted the Heart of Illinois Fair every year since 1949. The fair features livestock competitions, rides, concessions, motor contests and concerts.[38]

Tourism

Registered historic places

- Central National Bank Building

- Cumberland Presbyterian Church

- Grand Army of the Republic Memorial Hall

- Grandview Drive

- International Harvester Building

- John C. Proctor Recreation Center

- Judge Flanagan Residence

- Judge Jacob Gale House

- Madison Theatre

- North Side Historic District

- Peace and Harvest

- Peoria City Hall

- Peoria Cordage Company

- Peoria Mineral Springs

- Peoria Waterworks

- Pere Marquette Hotel

- Pettingill-Morron House

- Rock Island Depot and Freight House

- Springdale Cemetery

- West Bluff Historic District

Sports

| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peoria Chiefs | Midwest League | Baseball | Dozer Park | 1983 | 1 (2002) |

| Peoria Rivermen | Southern Professional Hockey League | Ice Hockey | Carver Arena | 2013 | 0 |

| Peoria Push Roller Derby | WFTDA Apprentice League | Roller Derby | Expo Gardens | 2010 | 0 |

| Peoria Rugby Football Club | D4 Midwest League | Rugby | Catholic Charities | 1958 | 0 |

| Peoria City | USL League Two | Association football | Shea Stadium (Peoria, Illinois) | 2020 | 0 |

Media

Peoria is the 153rd largest radio market in the United States[39] and Peoria-Bloomington is the 117th largest television market in the United States.[40]

The area has 14 commercial radio stations with six owners among them; four non-commercial full-power radio stations, each separately owned; five commercial television stations with two operating owners among them; one non-commercial television station; and one daily newspaper (Peoria Journal Star).

NOAA Weather Radio

NOAA Weather Radio station WXJ71 transmits from East Peoria and is licensed to NOAA's National Weather Service Central Illinois Weather Forecast Office at Lincoln, broadcasting on a frequency of 162.475 mHz (channel 4 on most newer weather radios, and most SAME weather radios). The station activates the SAME tone alarm feature and a 1050 Hz tone activating older radios (except for AMBER Alerts, using the SAME feature only) for hazardous weather and non-weather warnings and emergencies, along with selected weather watches, for the Illinois counties of Fulton, Knox, Marshall, Mason, McLean, Peoria, Putnam, Stark, Tazewell, and Woodford. Weather permitting, a tone alarm test of both the SAME and 1050 Hz tone features are conducted every Wednesday between 11 AM and noon.[41]

Activities

Civic Center

The Peoria Civic Center includes an arena, convention center, and theater, and was completed in the early 1980s, was designed by the famed late architect Philip Johnson. It completed a $55 million renovation and expansion by 2007.

The Hotel Pere Marquette finished renovations in 2013[42] with a skyway linking to the Peoria Civic Center. A new 10-story Courtyard has been built adjacent to this hotel, completing a hotel campus for larger conventions.

The Civic Center hosts the Bradley University Men's Basketball team, the IHSA Boys State Basketball Championships and State Chess Championship. Which claims to be the largest chess team tournament in the United States: Beginning in 2018, the teams were narrowed to 128 by the use of sectional elimination competitions, and as of 2018 the tournament has about 1500 players, including up to 8 players and 4 alternates per team.[43]

Renaissance Park

Renaissance Park was originally designated as a research park, originally established in May 2003 as the Peoria Medical and Technology District. It consisted of nine residential neighborhoods, Bradley University, the medical district, and the National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research. The Peoria NEXT Innovation Center opened in August 2007 and provides both dry and wet labs, as well as conference and office space for emerging start-up companies. Over $2 billion in research is conducted in Peoria annually.[44] While the Renaissance Park research park project never came to full fruition, many of the original ideas from the original Renaissance Park concept still continue on a smaller level via The Renaissance Park Community Association.[45]

The Block

The Block is a $100+ million project that contains}} the Peoria Riverfront Museum[46] and The Caterpillar Experience,[47] a museum and visitor's center showcasing Caterpillar past, present, and future. It is located in downtown Peoria along the Illinois River at the site formerly known as the Sears Block. The Block opened in October 2012.

Economy

Industry

Peoria's first major industry was started in 1830 by John Hamlin and John Sharp, who constructed the flour mill on Kickapoo Creek.[48] In 1837, another industry was begun with E.F. Nowland's pork planting industry. Many other industries started slowly in Peoria including carriage factories, pottery makers, wholesale warehousing, casting foundries, glucose factories, ice harvesting, and furniture makers.

Peoria became the first world leader for distilleries thanks to Andrew Eitle (1837) and Almiron S. Cole (1844).[49] During this time, Peoria held 22 distilleries and multiple breweries. Together, they produced the highest amount of internal revenue tax on alcohol of any single revenue district in the entire U.S. Peoria also was one of the major bootlegging areas during Prohibition and home to the famed mobsters, the Shelton brothers. This great success placed Peoria into a building boom of beautiful private homes, schools, parks, churches, as well as municipal buildings.

In addition to the distilleries came farm machinery manufacturing by William Nurse in 1837. Also, two men called Toby and Anderson brought the steel plow circa 1843, which gained immediate success. The dominant manufacturing companies in Peoria were Kingman Plow Co., Acme Harvester Co., Selby, Starr & Co., and Avery Manufacturing Co. In 1889, Keystone Steel & Wire developed the first wire fence and has since been the nation's leading manufacturer.[50][51]

Around the 1880s, businesses such as Rouse Hazard Co. in Peoria, were dealers and importers of bicycles and accessories worldwide. Charles Duryea, one of the cycle manufacturers, developed the first commercially available gasoline-powered automobile in the U.S. in 1893.

At this time, agricultural implement production declined, which led the earth moving and tractor equipment companies to skyrocket and make Peoria in this field the world leader. In 1925, Caterpillar Tractor Co. was formed from California based companies, Benjamin Holt Co. and the C.L. Best Tractor Co. Robert G. LeTourneau's earth moving company began its production of new scrapers and dozers in 1935 which evolved into Komatsu-Dresser, Haulpak Division.[52] Today, the joint venture between Komatsu and Dresser Industries has long since passed. The entity that remains is the off-highway truck manufacturing division for Komatsu America Corporation.

Retail

The city's largest mall is Northwoods Mall.[53] Other retail centers include The Shoppes at Grand Prairie,[54] Sheridan Village, Metro Centre,[55] Willow Knolls Court, and Westlake Shopping Center.

Businesses

- Archer Daniels Midland: Corn processing plant and ethanol producer

- Bergner's (until August 2018 when it went bankrupt and closed nationwide): Department store; started in 1889 in downtown Peoria and eventually bought out Carson Pirie Scott & Co. (now part of Bon-Ton)

- Caterpillar (until 2017 when its Headquarters (approx 300 positions) moved to Deerfield, Illinois): Heavy equipment and engine manufacturer. Caterpillar still maintains a large working force in the area in Management, Marketing, IT, Engineering and Labor Union manufacturing, as well as other positions.

- CEFCU: Credit union; started by Caterpillar employees; now serves residents of 14 counties in Central Illinois and 3 in California

- Komatsu America Corporation: World's second-largest mining equipment manufacturer has a large manufacturing facility in Peoria[56]

- Maui Jim (World Headquarters): Sunglasses manufacturer

- National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research: Largest USDA research facility; one of the facilities where mass production of penicillin was improved

- OSF Healthcare, which operates OSF Saint Francis Medical Center

- RLI Corp. (World Headquarters): Specialty insurance company

- Pioneer Railcorp (Corporate Headquarters): Railroad holding company for a number of American short-line railroads

- UnityPoint Health: Owns three hospitals in the area, two in Peoria

Top employers

According to Peoria's 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[57] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Caterpillar | 12,000 |

| 2 | OSF Saint Francis Medical Center | 12,000 |

| 3 | UnityPoint Health | 4,991 |

| 4 | Peoria Public Schools District 150 | 2,891 |

| 5 | Bradley University | 1,300 |

| 6 | Advanced Technology Services | 1,073 |

| 7 | Keystone Steel & Wire | 912 |

| 8 | City of Peoria | 888 |

| 9 | Peoria County | 831 |

| 10 | Citizens Equity First Credit Union | 814 |

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 1,467 | — | |

| 1850 | 5,095 | 247.3% | |

| 1860 | 14,045 | 175.7% | |

| 1870 | 22,849 | 62.7% | |

| 1880 | 29,259 | 28.1% | |

| 1890 | 41,024 | 40.2% | |

| 1900 | 56,100 | 36.7% | |

| 1910 | 66,950 | 19.3% | |

| 1920 | 76,121 | 13.7% | |

| 1930 | 104,969 | 37.9% | |

| 1940 | 105,087 | 0.1% | |

| 1950 | 111,856 | 6.4% | |

| 1960 | 103,162 | −7.8% | |

| 1970 | 126,963 | 23.1% | |

| 1980 | 124,160 | −2.2% | |

| 1990 | 113,504 | −8.6% | |

| 2000 | 112,936 | −0.5% | |

| 2010 | 115,007 | 1.8% | |

| Est. 2019 | 110,417 | [2] | −4.0% |

| [58] | |||

As of the census[59] of 2010, there were 115,021 people and 47,202 households residing in the city. The population density was 2,543.4 people per square mile (982.1/km2). There were 52,621 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 62.4% White, 26.9% Black or African American, 0.3% Native American, 4.6% Asian, and 3.6% of mixed races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.9% of the population. The city has a sizable, established Lebanese population with a long history in local business and government.

There were 45,199 households, out of which 29.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.6% were married couples living together, 15.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.5% were non-families. Individuals made up 33.2% of all households, and 11.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.39 and the average family size was 3.04.

The city population was 25.7% under the age of 18, 12.0% from 18 to 24, 27.2% from 25 to 44, 20.8% from 45 to 64, and 14.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $36,397. The per capita income for the city was $20,512. Some 18.8% of the population was below the poverty line.

Special censuses were conducted in 2004 and 2007 that noted a total increase of 8,455 in the city's population since the 2000 census.[60]

Government and politics

Peoria is a home rule municipality with a mayor and ten city council members. It has a council-manager form of government. The city is divided into five districts. Five council members are elected at-large via cumulative voting.

| Office | Office holder |

|---|---|

| Mayor | Jim Ardis |

| City Councilperson – District 1 | Denise Moore |

| City Councilperson – District 2 | Chuck Grayeb |

| City Councilperson – District 3 | Timothy Riggenbach |

| City Councilperson – District 4 | Jim Montelongo |

| City Councilperson – District 5 | Denis Cyr |

| City Councilperson – At Large | Rita Ali |

| City Councilperson – At Large | Zachary M. Oyler |

| City Councilperson – At Large | Sid Ruckriegel |

| City Councilperson – At Large | Elizabeth Jensen |

| City Councilperson – At Large | John L. Kelly |

| City/Township Clerk | Beth Ball |

| City Treasurer/Township Collector | Patrick Nichting |

| Township Supervisor | Frank Abdnour |

| Township Assessor | Max Schlafley |

Township of the City of Peoria

The Township of the City of Peoria (sometimes called City of Peoria Township) is a separate government from the City of Peoria, and performs the functions of civil township government in most of the city. The township was created by the Peoria County Board to match the boundaries of the City of Peoria, which until then had overlapped portions of Peoria Township (now West Peoria Township) and Richwoods Township.[62] The border of the township grew with the Peoria city limits until 1990, when it was frozen at its current boundaries, containing about 53 square miles (140 km2);[63] the City of Peoria itself has continued expanding outside the City of Peoria Township borders into Kickapoo, Medina, and Radnor township. In the years before the freeze, the Township of the City of Peoria had grown to take up most of the former area of Richwoods and what is now West Peoria Township.

Education

Peoria is served by four public K-12 school districts:

- Peoria Public Schools District 150 is the largest and serves the majority of the city. District 150 schools include dozens of primary and middle schools, as well as three public high schools: Richwoods High School, which hosts the competitive International Baccalaureate Program of study; Manual High School; and Peoria High School (Central), the oldest high school in Illinois. Until the end of the 2009–2010 school year, a fourth high school, Woodruff High School, closed. According to SchoolDigger, District 150 has the highest-ranking middle school (Washington Gifted Middle School).

- Peoria District 150 is also served by Quest Charter Academy, a STEM focused school serving grades 5-12. Quest is the only charter school in the area and began in 2010.

- Dunlap Community Unit School District 323 serves the far north and northwest parts of Peoria that were mostly outside the city before the 1990s. Dunlap schools has Dunlap High School, 2 Middle Schools and 5 Elementary schools.

- Limestone Community School District 310 serves a small portion of the western edge of the City of Peoria (western edges of Wardcliffe and Lexington Hills areas), but mainly serves the suburbs of Bartonville, Bellevue and surrounding towns.

- Peoria Heights School District 325 serves the suburb of Peoria Heights; however, parts of the City of Peoria immediately outside the Heights are in this school district.

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Peoria runs six schools in the city: five grade schools and Peoria Notre Dame High School. Non-denominational Peoria Christian School operates a grade school, middle school, and high school.

In addition, Concordia Lutheran School, Peoria Academy, Christ Lutheran School, and several smaller private schools exist.

Bradley University, Methodist College, OSF St. Francis College of Nursing, the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria, the Downtown and North campuses of Illinois Central College, and the Peoria campus of Roosevelt University are based in the city. Additionally, Eureka College and the main campus of Illinois Central College are located nearby in Eureka and East Peoria, respectively.

Infrastructure

Health and medicine

The health-care industry accounts for at least 25% of Peoria's economy. The city has three major hospitals: OSF Saint Francis Medical Center, UnityPoint Health – Methodist, and UnityPoint Health – Proctor. In addition, the Children's Hospital of Illinois, the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria, and the Midwest Affiliate of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital are located in the city. The hospitals are all located in a medical district around the junction of Interstate 74 and Knoxville Avenue, adjacent to downtown in the southeast of the city, except for UnityPoint Health – Proctor in the geographic center of the city. The surrounding towns are also supported by UnityPoint Health – Proctor, Pekin Hospital, Advocate Eureka Hospital, and the Hopedale Medical Complex. The Institute of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation was created from the "Peoria Plan for Human Rehabilitation," a model for medical and occupational rehabilitation launched in 1943 to integrate returning World War II veterans back into the workplace.

Transportation

Interstate and U.S. routes

The Peoria area is served by three Interstate highways: Interstate 74, which runs from northwest to southeast through the downtown area, Interstate 474, a southern bypass of I-74 through portions of Peoria and the suburbs of Bartonville and Creve Coeur, and Interstate 155, which runs south from I-74 in Morton to Interstate 55 in Lincoln which connects to Springfield and St. Louis. I-74 crosses over the Illinois River via the Murray Baker Bridge, while I-474 crosses via the Shade-Lohmann Bridge. The nearest metropolitan centers accessible on I-74 are the Quad Cities to the west, and Bloomington-Normal to the east.

From 2004 to 2006, Interstate 74 between Interstate 474 on the west and Illinois Route 8 on the east was reconstructed as part of the Upgrade 74 project.

In addition, U.S. Route 150 serves as the main arterial for the northern portion of the Peoria area, becoming War Memorial Drive before heading west towards Kickapoo. It enters from the McClugage Bridge; east of the bridge, U.S. 150 runs southeast to Morton.

State routes

The following state routes run through Peoria:

- Illinois Route 6 runs along the northwestern portion of the city as an extension of I-474. It is a four-lane freeway that runs from the I-74/474 intersection northeast to Illinois Route 29 south of Chillicothe. It is marked as a north–south road.

- Illinois Route 8 roughly parallels I-74 to the south. It enters Peoria from Elmwood and runs southeast through the city, passing just southwest of the downtown area. Illinois 8 crosses into East Peoria via the Cedar Street Bridge with 116. Illinois 8 is marked as an east–west road.

- Illinois Route 29 runs through Peoria along the Illinois River from Chillicothe through downtown Peoria. It then joins Interstate 74 across the Murray Baker Bridge. Illinois 29 is marked as a north–south road, and is called Galena Road north of U.S. 150.

- Illinois Route 40 (formerly 88) enters Peoria from the north as Knoxville Avenue. It runs south through the center of the city and exits southeast over the Bob Michel Bridge. Illinois 40 is marked as a north–south road.

- Illinois Route 91 briefly enters Peoria at the intersection with U.S. 150 in the far northwestern portion of the city. Traffic on Illinois 91 mainly accesses the Shoppes at Grand Prairie,[64] or continues to Dunlap.

- Illinois Route 116 enters from the west at Bellevue. It runs directly east and crosses into East Peoria over the Cedar Street Bridge.

The planned Illinois Route 336 project will also connect Illinois 336 with I-474 between Illinois 8 and Illinois 116. Construction on the segment nearest Peoria has not started, nor has funding been allocated.

Rail transportation

Metro Peoria is served by ten common carrier railroads. Four are Class I railroads: BNSF, CNR, Norfolk Southern, and Union Pacific. The last one, Union Pacific, has a north–south oriented line which skirts the west edge of the city but a line branches off of it to enter Peoria. One Class II/Regional, Iowa Interstate, serves the city, coming out of Bureau Junction, Illinois. Five Class III/Shortline railroads: Central Illinois Railroad, which operates a portion of the city-owned Peoria, Peoria Heights and Western Railroad; three Genesee and Wyoming-owned operations: Toledo, Peoria and Western Railway, which runs next to US 24 east to Logansport, Indiana (formally owned by Rail America), Illinois & Midland Railroad (the former Chicago and Illinois Midland, comes up from Springfield and Havana) and Tazewell and Peoria Railroad (leases the Peoria and Pekin Union Railway from its owners Canadian National, Norfolk Southern and Union Pacific); Pioneer Railcorp's Keokuk Junction Railway (which now owns the Toledo, Peoria and Western's West End from Lomax and La Harpe in Western Illinois, plus the branch from Keokuk).

There is no passenger rail connecting Peoria to other urban centers, although this possibility and the possibility of rail service that connects St. Louis to Chicago (by way of Springfield, Peoria, Bloomington-Normal, and Pontiac) has been and is being investigated.[65]

Peoria was a minor passenger rail hub until the 1950s. Several Midwestern railroads fed into Peoria Union Station until 1955. The Rock Island Railroad operated trains into its Rock Island Depot.

Peoria's last intercity rail service ended when the Rock Island Railroad ran its last Peoria Rocket train into the Rock Island Depot in 1978. The area's last intercity rail service ended in 1981, when Amtrak withdrew the Prairie Marksman (Chicago-East Peoria), which stopped in nearby East Peoria. The nearest Amtrak rail service is at Galesburg to the northwest and Bloomington to the southeast.

Public transportation

Public bus service is provided by the Greater Peoria Mass Transit District, which operates 21 bus routes under the name CityLink, that serve the city, Illinois Central College and much of East Peoria, Illinois, Peoria Heights, West Peoria, and points between Peoria and Pekin.[66]

Aviation

The General Wayne Downing Peoria International Airport is located west of Peoria. The airport is served by 4 passenger airlines (United, American, Delta, and Allegiant Air) and numerous cargo carriers. Nonstop destinations include Chicago, Atlanta, Dallas/Ft. Worth, Las Vegas, Minneapolis/St. Paul, Detroit, Houston, Phoenix, and Charlotte.[67] Cargo carriers serving Peoria include UPS and Airborne Express (now DHL).

Mount Hawley Auxiliary Airport, on the north end of the city, also accepts general aviation.

Points of interest

- Civil War Monument at County Courthouse Plaza

- Grandview Drive along the Illinois River bluff in Peoria and Peoria Heights

- Glen Oak Park, including Glen Oak Zoo and George L. Luthy Memorial Botanical Garden

- Spirit of Peoria − paddle wheel riverboat

- Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Immaculate Conception (Peoria, Illinois) (also known as St. Mary's Cathedral)

- Scottish Rite Cathedral

- Wildlife Prairie State Park, about 10 mi (16 km) west of the city

- Peoria Riverfront Museum and Caterpillar Visitor Center along the downtown waterfront

Notable people

- Gerald Thomas Bergan

- Lydia Moss Bradley, founded Bradley University.

- Howard Brown

- Dan Fogelberg

- Betty Friedan

- Joe Girardi

- John Grier Hibben

- Jim Jordan, (Fibber McGee) Fibber McGee and Molly radio show

- Marian Jordan, (Molly) Fibber McGee and Molly radio show

- Tim Kelley

- Tami Lane

- Ralph Lawler

- Shaun Livingston

- Bobby McGrath

- Sherrick McManis

- Bob Michel

- Richard Pryor, a stand-up comedian

- Brian Randle (born 1985), basketball player for Maccabi Tel Aviv of the Israeli Basketball Super League

- Gary Richrath

- Bob Robinson

- Fulton J. Sheen

- Dan Simmons

- Donald Smith (concert film producer) The Who/The Rolling Stones/Pearl Jam

- Edward W. Snedeker

- Dr. Jokichi Takamine, lived in Peoria in the 1890s.[68]

- Jim Thome

- Richard A. Whiting

- Mike Zimmer

Notable events

- September 19 to October 21, 1813 – Peoria War

- 1844 – Abraham Lincoln came to Peoria to get involved in the Aquilla Wren divorce case and took it to the Supreme Court of Illinois

- October 16, 1854 – Abraham Lincoln first publicized his stand that the United States should move towards restricting and eventually eliminating slavery, a position directly against historic compromises such as the Kansas–Nebraska Act. The speech, which was possibly similar to one given in Springfield, Illinois, 12 days earlier, followed the speech of Stephen A. Douglas, whom Lincoln would later debate regularly in the Lincoln–Douglas debates of 1858.[69]

- April 15, 1926 – Charles Lindbergh's first air mail route, Contract Air Mail route #2, began running mail from Chicago to Peoria to Springfield to St. Louis and back.[70] There is nothing to substantiate the local legend that Lindbergh offered Peoria the chance to sponsor his trans-Atlantic flight and call his plane the "Spirit of Peoria," but he does state that he first pondered the journey after taking off from the Peoria air mail field.[71]

- 1942 – Penicillium chrysogenum, the fungus originally used to industrially produce penicillin, was first isolated from a mouldy cantaloupe found in a grocery store in Peoria.

- April 3, 1967 – The trial of mass murderer Richard Speck begins at the Peoria County courthouse, after a change of venue from Chicago to ensure a fair trial.

- Theodore Roosevelt called Grandview Drive, a street on the bluffs overlooking the Illinois River "the world's most beautiful drive."[72] The Peoria radio station and CBS television affiliate WMBD attached the description to its call sign.

- October 5, 1984 – Michael Jordan made his first appearance as a professional player (Chicago Bulls), in Peoria, in a preseason game against the Indiana Pacers. Jordan scored 18 points in 29 minutes in Chicago's 102–98 victory.

Awards

- Peoria has been awarded the All-America City Award four times (1953, 1966, 1989 and 2013).

- In 2007, Forbes ranked Peoria No. 47 out of the largest 150 metropolitan areas in its annual "Best Places for Business and Careers." Peoria was evaluated on the cost of doing business, cost of living, entertainment opportunities, and income growth.[73]

- In 2005, Bert Sperling and Peter Sanders' "Best Places to Live Rankings" among 331 metropolitan areas placed Peoria No. 51, citing "low cost of living, low cost of housing, and attractive residential areas" as the main pros to the area.[74]

- Peoria was ranked a 5 Star Logistics City by Expansion Management Magazine in 2007[75]

- Peoria consistently ranks in the Top 10 Best Mannered Cities in America as compiled by etiquette expert Marjabelle Young Stewart.[76]

- Peoria was ranked as one of the "50 Next Great Adventure Towns" in the US in the September 2008 issue of National Geographic Adventure magazine. This was mainly based on the extensive mountain biking trails in and around the city and the live entertainment options found on the RiverFront.[77]

- In 2009, Peoria was ranked 16th best city with a population of 100,000−200,000 ("Mighty Micros") in the U.S. Next Cities List. The list was compiled by Next Generation Consulting, a firm which studies and consults on hiring trends and workplace issues nationwide, and the indexes used were divided into earning, learning, vitality, around town, after hours, cost of lifestyle and social capital. Top Mighty Micro was Fort Collins, Colorado; the other Mighty Micro in Illinois was Springfield at No. 5.[78]

- In 2009, Peoria was ranked No. 5 best mid-sized city to launch a small business by CNN Money and Fortune Small Business.[79]

- Milken Institute released its Best Performing Metropolitan Areas listing for 2008 and the Peoria Area ranked No. 33 among the top 200 largest metropolitan areas in the country. It was the highest ranking area in Illinois with Chicago coming in next at No. 148.[80]

Religion

- Anglican Church in North America, Diocese of Quincy − diocese seat is in Peoria

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Peoria

Peoria in popular culture

The theme of Peoria as the archetypal example of middle American culture runs throughout American culture, appearing in movies and books, on television and radio, and in countless advertisements as either a filler place name, the representative of mainstream taste, hence the phrase "Will it play in Peoria?"[81][82][83]

Music

On the Songs: Ohia album called The Magnilia Electric Co (2003) there is a song by Jason Molina called "Peoria Lunch Box Blues".

- In Sufjan Stevens' album Illinois, Peoria is the subject of the song titled "Prairie Fire That Wanders About." Stevens makes reference to multiple figures in Peoria's history, including Lydia Moss Bradley, and also speaks of Peoria's Santa Claus parade, the longest running in the nation.

- "Peoria" by King Crimson was recorded at The Barn in Peoria on March 10, 1972, included in the live album Earthbound.

News commentary

- In 1977, the news magazine Time used Peoria as a form of "et cetera" in an article on the proliferation of new vineyards in America, calling them "the new Chateaux Peorias...."

- A 2009 issue of National Geographic states in its "The Big Idea" section that electron-dispensing filling stations, a now-possible idea difficult to implement on a large scale, will soon "play even in Peoria".[84]

- Peoria ranked as second 'worst city for Black Americans' to live in 2017 study by 24/7 Wall Street [85][86]

See also

- General American

- Will it play in Peoria?

- List of places named Peoria

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "29 ZIP Code Results for listing Peoria, IL a "Primary city"". Unitedstateszipcodes.org. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Cities with 25,000 population or more, table C-1: Area and Population". County and City Data Book: 2007. United States Census Bureau. 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-03-08. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- "The First European Settlement in Illinois". Peoria's History. Peoria, Illinois: Peoria Historical Society. Archived from the original (website) on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2020-07-17.

- Lincoln, Abraham (2001). Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Volume 2.

- Springfield, Mailing Address: 413 S. 8th Street; Us, IL 62701 Phone:492-4241 Contact. "Peoria Speech, October 16, 1854 - Lincoln Home National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2019-06-20.

- "Peoria | Illinois, United States". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-06-20.

- "Caterpillar to Move Headquarters to Chicago Suburb of Deerfield, Ill". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- "Caterpillar's move to Deerfield made official in SEC filing". The State Journal-Register. Retrieved 2018-08-05.

- "The Phrase That Put Peoria on the Map". PeoriaMagazines.com. Retrieved 2019-06-20.

- Peoria Illinois History. peoria.com. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- Scheetz, George H. "Peoria." In Place Names in the Midwestern United States. Edited by Edward Callary. (Studies in Onomastics; 1.) Mellen Press, 2000. ISBN 0-7734-7723-3

- Edward Callary, Place Names of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2009), p. 273.

- "The History of Peoria, Arizona". City of Peoria, Arizona. Archived from the original on 2008-11-10. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- Slater, Wayne (2 November 1980). "Famed Brothels Gone, Prostitutes Remain: Play in Peoria Not Like in Old Days". Los Angeles Times.

- Vanocur, Sander (20 March 1977). "Richard Pryor: It's a Long Way from Peoria--And It's Your Serve". The Washington Post.

- "G001 - Geographic Identifiers - 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2015-12-27.

- "Average Weather for Peoria, IL − Temperature and Precipitation". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- "IL Peoria GTR Peoria AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- "WMO Climate Normals for Peoria/Greater Peoria ARPT, IL 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- Marotti, Lauren Zumbach, Ally. "Caterpillar bypasses Chicago, picks Deerfield for global headquarters". Chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "Penicillin: Opening the Era of Antibiotics". National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research website. 2006-04-07. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2007-06-19.

- "Alexander Fleming Discovery and Development of Penicillin - Landmark - American Chemical Society". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "Promoting Grandview Drive & Theodore Roosevelt's connection – 'Word' on the Web". Journal Star. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- "Welcome to the Peoria Park District, Peoria, Illinois, USA". Peoriaparks.org. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- "Before It Became The Museum Block". InterBusinessIssues. January 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- Tori Phelps. "Annual Fine Art Fair". PeoriaMagazines.com. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Hatch, Danielle. "Say hello to Africa". Pjstar.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "Top International Field Expected at Steamboat Classic 4 Mile". Cool Running. San Diego, California: The Active Network, Inc. 2006-06-15. Archived from the original on 2007-04-07. Retrieved 2007-06-19.

- "Santa Claus Parade". PACE. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- "Sister City US Listings – Directory Search Results – Illinois". Washington, D.C.: Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- "Peoria Becomes Sister City with Aitou, Lebanon - CIProud". Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- "Peoria Players History". 2007-03-19. Archived from the original on September 21, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-19.

- "A Peoria Tradition for Six Decades". Peoriamagazines.com. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- "Expo Gardens". expogardensinc.com. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "Market Survey Schedule & Population Rankings" (PDF). Arbitron. 2011-09-12. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

- "Local Television Market Universe Estimates: Comparisons of 2009–10 and 2010–11 Market Ranks" (PDF). New York City: The Neilsen Company. 2010-08-27. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- Lincoln, National Weather Service. "NOAA Weather Radio Station WXJ-71 (Peoria)". NOAA Weather Radio Station WXJ-71 (Peoria). Lincoln National Weather Service. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- "Pere Marquette reopens with a 'spectacular' new look". Peoria Journal Star. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- "2018 Chess" (Press release). Illinois High School Association. February 5, 2018. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- "Peoria Progress". Central Illinois Business Publishers. 2014. p. 14.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-10. Retrieved 2015-02-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Home". Peoria Riverfront Museum. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- "Visitors Center". Caterpillar. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- Ballance, Charles (1870). The History of Peoria, Illinois, pp. 127-28. N.C. Nason.

- Ballance (1870), pp. 135-36.

- Poland China World. Poland China Record Association. 1915. pp. 3–.

- James Montgomery Rice (1912). Peoria City and County, Illinois: A Record of Settlement, Organization, Progress and Achievement. S. J. Clarke. pp. 884–.

- "Peoria Historical Society". Peoriahistoricalsociety.org. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "Northwoods Mall, a Simon Mall – Peoria, IL". Simon.com. Archived from the original on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- "The Shoppes at Grand Prairie". The Shoppes at Grand Prairie. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "Metro Centre of Peoria Illinois - For Peoria by Peoria". Shopmetrocentre.com. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "Komatsu America Corp. - Locations". Komatsuamerica.com. 2014-01-29. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- "City of Peoria CAFR" (PDF). Peoriagov.org. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places of 50,000 or More, Ranked by July 1, 2014 Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-06-09. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- Ardis, Jim (February 2008). "State of the City 2008". InterBusiness Issues. Peoria, Illinois: Central Illinois Business Publishers, Inc. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- "City of Peoria, Illinois". Ci.peoria.il.us. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- Illinois Attorney General's Office (December 1908). Biennial Report of the Attorney General of the State of Illinois. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Journal Co. p. 457. Retrieved 2019-07-28.

- "Peoria Township Boundary". Peoria, Illinois: City of Peoria Township. Retrieved 2019-07-28.

- "Directions". Shoppesatgrandprairie.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-20. Retrieved 2013-09-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "CityLink maps". Greater Peoria Mass Transit District (CityLink). 2007-05-16. Archived from the original on 2007-07-09. Retrieved 2007-06-19.

- "Peoria International Airport". Flypia.com. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- http://www.soyinfocenter.com/books/155 §1891 Feb. 28

- "Abraham Lincoln at Peoria, IL: The Turning Point". Lincolnatpeoria.com. 2009-06-18. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Contract Air Mail Route No.2: Chicago − Peoria − Springfield − St. Louis Archived December 31, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Includes images of Peoria-addressed and Peoria-postmarked postcards. Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- Christopher Glenn (August 12, 2012). "Lindbergh Never Considered "Spirit of Peoria"". Peoria Journal Star Inc. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- "GRAND VIEW DRIVE AND PARK". Peoria Park District. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- "Forbes Ranks Peoria No. 47 on Cost of Doing Business Index". Economic Development Council for Central Illinois. Archived from the original on April 4, 2006. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- "2005 Best Places to Live". Sperling's Best Places. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- "Peoria Among The Nation's Top Logistics-Friendly Cities". Economic Development Council for Central Illinois. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- Glanton, Dahleen (2006-06-14). "America's best-mannered city" (PDF). Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-08-31. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

Three Illinois cities − Peoria, Moline and Rock Island − have consistently made the Top 10.

- "Best Places to Live: Where to Live and Play Now!". National Geographic Adventure. September 2008.

- "Best Cities for Next Gen Workforce – What's more important than jobs?". Madison, Wisconsin: Next Generation Consulting. 2009-06-11. Archived from the original on 2009-06-14. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- "Best Places to Launch". CNN.

- "2009 Best Performing Cities". Archived from the original on 2009-11-14.

- "Will it Play in Peoria?". StoryCorps. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- "Peoria, IL". Forbes. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- Borcover, Alfred (9 April 2010). "Play in Peoria". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- "The Future of Filling Up". National Geographic. 15 October 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- "These are the 5 worst cities for black Americans". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- "The Worst Cities for Black Americans". 247wallst.com. Retrieved 2018-11-17.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about Peoria. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peoria, Illinois. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- City of Peoria, Illinois — official government site

- Peoria County GIS Open Data Portal — geographic property data and mapping site for Peoria city and county

- Map of Peoria Neighborhoods

- Peoria 1719–1730

Notable webcams

- IDOT Getting Around Peoria Traffic Viewer − Illinois Department of Transportation site with traffic conditions map and cameras of three Interstate 74 interchanges

- Journal Star BridgeCam − live and time-lapse view of the McClugage Bridge, U.S. Route 150, and nearby areas, from the Peoria Journal Star building

- Bradley University webcams