Olympic Stadium (Montreal)

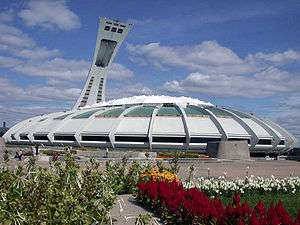

Olympic Stadium[1] (French: Stade olympique) is a multi-purpose stadium in Montreal, Canada, located at Olympic Park in the Hochelaga-Maisonneuve district of the city. Built in the mid-1970s as the main venue for the 1976 Summer Olympics, it is nicknamed "The Big O", a reference to both its name and to the doughnut-shape of the permanent component of the stadium's roof. The tower standing next to the stadium, The Montreal Tower, is the tallest inclined tower in the world with an angle elevation of 45 degrees. It is also called "The Big Owe" to reference the astronomical cost of the stadium and the 1976 Olympics as a whole.[6]

Stade olympique | |

The Big O | |

| |

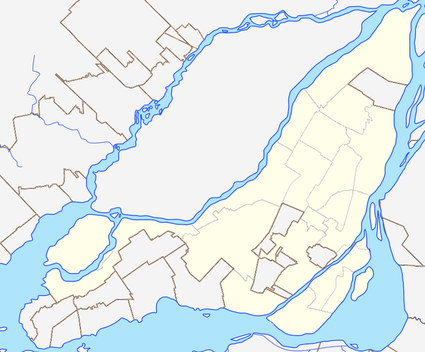

Olympic Stadium Location in Montreal  Olympic Stadium Location in Quebec  Olympic Stadium Location in Canada | |

| Address | 4545 Pierre-de-Coubertin Avenue |

|---|---|

| Location | Montreal, Quebec, Canada |

| Coordinates | 45.558°N 73.552°W |

| Public transit | Montreal Metro (STM): Société de transport de Montréal |

| Owner | Régie des Installations Olympiques (Government of Quebec) |

| Capacity | Permanent capacity: 56,040 (1992–present)[1] 1976 Summer Olympics: 73,000 (1976–1992) Baseball: 45,757 (1992–present)[2] Soccer: 61,004[3] Football: 66,308[4] Concert: 78,322 |

| Field size | Foul Lines – 325 feet (99 m) (1977), 330 feet (101 m) (1981), 325 feet (99 m) (1983) Power Alleys – 375 feet (114 m) Centre Field – 404 feet (123 m) (1977), 405 feet (123 m) (1979), 404 feet (123 m) (1980), 400 feet (122 m) (1981), 404 feet (123 m) (1983) Backstop – 62 feet (19 m) (1977), 65 feet (20 m) (1983), 53 feet (16 m) (1989) |

| Surface | Grass (1976 and June 2, 2010) AstroTurf (1977–2001; 2005–06) Defargo Astrograss (2002–03) FieldTurf (2003–2005) Team Pro EF RD (soccer; 2007–July 2014) Xtreme Turf by Act Global (July 2014–present) FIFA Certified |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | April 28, 1973 |

| Opened | July 17, 1976, 44 years ago April 15, 1977 (baseball) |

| Construction cost | C$ 770 million C$ 1.47 billion (2006 – including additional costs, interest and repairs) |

| Architect | Roger Taillibert[5] |

| Tenants | |

| Montreal Expos (MLB) (1977–2004) Montreal Alouettes (CFL) (1976–86, 1996–97, part-time 1998–2013) Montreal Manic (NASL) (1981–83) Montreal Machine (WLAF) (1991–92) Montreal Impact (MLS) (2012–present, select games) | |

| Website | |

| Parc Olympique Quebec | |

The stadium is the largest by seating capacity in Canada. After the Olympics, artificial turf was installed and it became the home of Montreal's professional baseball and football teams. The Montreal Alouettes of the CFL returned to their previous home of Molson Stadium in 1998 for regular season games, but continued to use Olympic Stadium for playoff and Grey Cup games until 2014 when they returned to Molson Stadium for all of their games. Following the 2004 baseball season, the Expos relocated to Washington, D.C., to become the Washington Nationals. The stadium currently serves as a multipurpose facility for special events (e.g. concerts, trade shows) with a permanent seating capacity of 56,040.[1] The capacity is expandable with temporary seating. The Montreal Impact of Major League Soccer (MLS) use the venue on occasion, when demand for tickets justifies the large capacity or when the weather restricts outdoor play at nearby Saputo Stadium in the spring months.

The stadium has not had a main tenant since the Expos left in 2004. Despite decades of use, the stadium's history of numerous structural and financial problems has largely branded it a white elephant.

Incorporated into the north base of the stadium is the Montreal Tower, the world's tallest inclined tower at 175 metres (574 ft). The stadium and Olympic Park grounds border Maisonneuve Park, which includes the Montreal Botanical Garden, adjacent to the west across Rue Sherbrooke (Route 138).

History

Background and architecture

As early as 1963, Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau sought to build a covered stadium in Montreal.[7] A covered stadium was thought to be all but essential for Drapeau's other goal of bringing a Major League Baseball team to Montreal, given the cold weather that can affect the city in April, October and sometimes even September. In 1967, soon after the National League granted Montreal an expansion franchise for 1969, Drapeau wrote a letter promising that any prospective Montreal team would be playing in a covered stadium by 1971. However, even as powerful as he was, he did not have the power to make such a guarantee on his own authority. Just as Charles Bronfman, who was slated to become the franchise's first owner, was ready to walk away, Drapeau had his staffers draw up a proposal for a stadium. It was enough to persuade Bronfman to continue with the effort.[8]

The stadium was designed by French architect Roger Taillibert to be an elaborate facility featuring a retractable roof,[5] which was to be opened and closed by cables suspended from a huge 175-metre (574 ft) tower – the tallest inclined structure in the world, and the sixth tallest structure in Montreal. The design of the stadium resembles that of the Australian Pavilion at Expo '70 in Osaka, Japan.[9] Soon after Montreal was awarded the 1976 Games, Drapeau struck a secret deal with Taillibert to build the stadium. It only came to light in 1972.[8]

The Olympic swimming pool is located under this tower. An Olympic velodrome (since converted to the Montreal Biodome, an indoor nature museum) was situated at the base of the tower in a building similar in design to the swimming pool. The building was built as the main stadium for the 1976 Summer Olympic Games. The stadium was host to various events including the opening and closing ceremonies, athletics, football finals, and the team jumping equestrian events.[10]

The building's design is cited as a masterpiece of Organic Modern architecture.[11] Taillibert based the building on plant and animal forms, aiming to include vertebral structures with sinews or tentacles, while still following the basic plans of Modern architecture.[11]

Construction

The stadium was originally slated to be finished in 1972, but the grand opening was cancelled due to a strike by construction workers. The Conseil des métiers de la construction union headed by André "Dédé" Desjardins kept the construction site in "anarchic disorder" until the Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa bought him off in a secret deal.[12] In his 2000 book Notre Cher Stade Olympique, Taillibert wrote "If the Olympic Games took place, it was thanks to Dédé Desjardins. What irony!"[12] Further delays ensued due to the stadium's unusual design and Taillibert's unwillingness to back down from his original vision of the stadium even in the face of escalating costs for raw materials. It did not help that the original project manager, Trudeau et Associés, seemed to be incapable of handling some of the most basic construction tasks. The Quebec provincial government finally lost patience with the delays and cost overruns in 1974, and threw Taillibert off the project.[8]

Additionally, the project was plagued by circumstances beyond anyone's control. Work slowed to a snail's pace for a third of the year due to Montreal's typically brutal winters. As a result, the stadium and tower remained unfinished at the opening of the 1976 Olympic Games.[8][13]

The roof materials languished in a warehouse in Marseille until 1982, and the tower and roof were not completed until 1987.[7][14] It would be another year before the 66-tonne, 5,500 m2 (59,000 sq ft) Kevlar roof (designed and built by Lavalin) could retract. Even then, it could not be used in winds above 40 km/h (25 mph). Ultimately, it was only opened and closed 88 times.[7]

Observatory

When construction on the stadium's tower resumed after the 1976 Olympics, a multi-storey observatory was added to the plan, accessible via an inclined elevator, opened in 1987, that travels 266 metres (873 ft) along the curved tower's spine. The elevator cabin ascends from base of the tower to upper deck in less than two minutes at a rate of 2.8 m/s (6.3 mph), with space for 76 persons per trip and a capacity of 500 persons per hour. The cabin is designed to remain level throughout its trip, while providing a panoramic view to its passengers.

The elevator faces north-east, offering a view to the north, south and east. It overlooks the Olympic Village, the Biodome, the Botanical Gardens and Saputo Stadium. The Olympic Park, the stadium's suspended roof and downtown Montreal can be viewed from the south-west facing Observatory at the top of the tower.

Stadium financing

_as_seen_at_night.jpg)

Despite initial projections in 1970 that the stadium would cost only C$134 million to construct, strikes and construction delays served to escalate these costs. By the time the stadium opened (in an unfinished form), the total costs had risen to C$1.1 billion.

The Quebec government introduced a special tobacco tax in May 1976 to help recoup its investment. By 2006, the amount contributed to the stadium's owner, the Olympic Installations Board (OIB) (fr: Régie des Installations Olympiques), accounted for 8% of the tax revenue earned from cigarette sales. The 1976 special tobacco tax act stipulated that once the stadium was paid off, ownership of the facility would be returned to the City of Montreal.

In mid-November 2006, the stadium's costs were finally paid in full, more than 30 years after it opened.[6] The total expenditure (including repairs, renovations, construction, interest, and inflation) amounted to C$1.61 billion, making it—at the time all costs were paid off—the second most expensive stadium built (after Wembley Stadium in London).[15] Despite initial plans to complete payment in October 2006, an indoor smoking ban introduced in May 2006 curtailed the revenue gathered by the tobacco tax.[6] By 2014, the stadium's expense ranking had fallen to fifth, with the construction of costlier venues like MetLife Stadium, AT&T Stadium, and the new Yankee Stadium. Perceived by many to be a white elephant, the stadium has also been dubbed The Big Owe due to its astronomical cost.

The stadium has generated on average $20 million in revenue each year since 1977. It is estimated that a large-scale event such as the Grey Cup can generate as much as $50 million in revenue.[16]

Continuing problems

Although the tower and retractable roof were not completed in time for the 1976 Olympics, construction on the tower resumed in the 1980s. During this period, however, a large fire set the tower ablaze, causing damage and forcing a scheduled Expos home game to be postponed. In 1986, a large chunk of the tower fell onto the playing field prior to another Expos game August 29 vs. San Diego Padres forcing a doubleheader on August 30.[17][18]

In January 1985, approval was given by the Quebec government to complete the project and install a retractable roof, financed by an Olympic cigarette tax in the province.[19] The tower construction and installation of the orange-coloured Kevlar roof were completed by April 1987,[20] a decade later than planned. The roof experienced numerous rips, allowing rain to leak into the stadium.[21][22]

As part of various renovations made in 1991 to improve the stadium's suitability as a baseball venue, 12,000 seats were eliminated, most of them in distant portions of the outfield, and home plate was moved closer to the stands.

On September 8 of that year, support beams snapped and caused a 55-long-ton (62-short-ton; 56 t) concrete slab to fall onto an exterior walkway. No one was injured, but the Expos had to move their final 13 home games of that season to the opponents' cities. The Expos hinted that the 1992 season was at risk unless the stadium was certified safe. In early November, engineers found the stadium was structurally sound. However, it took longer to certify the roof as safe because it had been badly ripped in a June windstorm.[7] For the 1992 season, it was decided to keep the roof closed at all times. The Kevlar roof was removed in May 1998, making the stadium open-air for the 1998 season. Later in 1998, a $26 million non-retractable opaque blue roof was installed.

In 1999, a 350 m2 (3,770 sq ft) portion of the roof collapsed on January 18, dumping ice and snow on workers that were setting up for the annual Montreal Auto Show.[18][23] The auto show and a boat show the following month were canceled,[24] and the auto show left the venue for good (since then, the Montreal Auto Show has usually been held at the Palais des congrès de Montréal). Repaired once again, the roof was modified to better withstand winter conditions: the OIB installed a network of pipes to circulate heated water under the roof to allow for snow melting. Despite these corrective measures, the stadium floor remained closed from December to March.[25] Birdair, the fabric provider and designer of the roof, was later sued for the roof failure.[26] The installer of the roof, Danny's Construction, having suffered tremendous cost overruns along with its subcontractor Montacier, due to changes in the plans and specifications and delays, was terminated during the construction, and Birdair completed the project. Danny's Construction sued Birdair in 1999.[27] In February 2010, after a lengthy trial, the Quebec Superior Court awarded a judgement in favour of Danny's Construction and dismissed Birdair's countersuit.[28]

The stadium's condition suffered considerably in the early 21st century. During the Expos' final years in Montreal, it was coated with grime, and much of the concrete was chipped, stained, and soiled.[29][30]

Plans for a third roof

In 2009, the stadium received approval to remain open in the winter, provided weather conditions are favourable.[31] However, the Olympic Installations Board issued a report stating that the roof was unsafe during heavy rainfall or more than 8 centimetres (3.1 in) of snow, and that it rips 50 to 60 times a year. The city fire department warned in August 2009 that without corrective measures, including a new roof, it may order the stadium closed. Events cannot be held if more than 3 centimetres (1.2 in) of snow are predicted 24 hours in advance, such as caused postponement of the Montreal Impact home opener soccer match in March 2014. A contract for a new permanent steel roof was awarded in 2004, with an estimated $300 million price tag. In June 2010, the Olympic Installations Board sought approval from the provincial government for the contract.[32] In May 2011 a committee was formed to study the future of the stadium and improve the usage of the stadium, pool, and sports centre.[33][34]

A slab of concrete measuring approximately 8 by 12 metres (26 by 39 ft) fell from the roof of the stadium's underground parking facility on March 4, 2012. There were no injuries.[35] The roof continues to deteriorate, with 7,453 tears as of May 2017,[36] limiting use of the venue in winter to when there are three or fewer centimetres of snow on the roof.[37]

In 2015, a new high definition scoreboard was installed, replacing the aging two-panel display dating back to the stadium's renovations in 1992.[38]

In November 2017 the Quebec government approved a new roof, estimated to cost $250 million.[39] The Olympic Installations Board has estimated the cost of demolishing the stadium would be between $500 and $700 million,[40] though this figure is based on a preliminary two-month study and thus has a high margin of error.[41] The new roof would be removable, allowing the stadium to either be open-air or enclosed, consistent with the intent of the original roof.[39]

Post-Olympic use

Gridiron football

The Canadian Football League's Montreal Alouettes became the stadium's first major post-Olympic tenant when they moved their home games there halfway through the 1976 season. Capacity was reduced from its Olympic capacity of 72,000 to 58,500, but leapt to 66,308 when the natural grass was replaced with AstroTurf ahead of the 1977 season.[7] The Alouettes remained there through 1986, the franchise's final season of operations; the team would shut down shortly after the start of the 1987 season. A revived Alouettes franchise returned for the 1996 and 1997 seasons, but then moved to the Percival Molson Stadium in 1998, only using the larger Olympic Stadium for select regular-season and home playoff games. As of 2008, the franchise uses Olympic Stadium for playoff games only. Due to the increased popularity of the Alouettes and the small capacity of Percival Molson Stadium, the team considered returning to Olympic Stadium on a full-time basis, but instead renovated Percival Molson Stadium to increase its capacity.[42] In addition, the stadium holds the record for the largest Grey Cup attendance, that of the 1977 Grey Cup game, in which the hometown Montreal Alouettes defeated the Edmonton Eskimos, 41-6 before 68,318 spectators; this despite a local transit strike and harsh winter weather conditions.[43]

Olympic Stadium has hosted the Grey Cup a total of six times, most recently in 2008 when the Calgary Stampeders defeated the hometown Alouettes. The stadium holds the record for nine of the ten largest crowds in CFL history, which include five regular-season and four Grey Cup games. A single-game record crowd numbering 69,083 attended a game played on September 6, 1977 between the Alouettes and Toronto Argonauts.[44]

In 1991 and 1992, the stadium was the home of the Montreal Machine of the World League of American Football. This included hosting World Bowl '92 on June 6, 1992, in which the Sacramento Surge defeated the Orlando Thunder 21–17 before 43,789.[45]

In 1988 (Jets and Browns) and 1990 (Steelers and Patriots), NFL pre-season games were played at Olympic Stadium.[46][47]

Baseball

In 1977, the stadium replaced Jarry Park Stadium as the home ballpark of the National League's Montreal Expos. As a part of the team's franchise grant, a domed stadium was supposed to be in place for the 1972 baseball season. However, due to the delays in constructing Olympic Stadium, until 1977, the Expos annually sought and received a waiver to remain at Jarry. As late as January 1977, it was thought the Expos would have to play at least part of the 1977 season at Jarry as well. The Parti Québécois' landslide victory in the 1976 provincial elections caused the Expos to break off lease talks. However, an agreement was reached in February, and an official announcement came in March.[7]

The Expos regularly played 81 home games every season until 2003, when they played 22 home games in Puerto Rico at Hiram Bithorn Stadium in San Juan. The Expos played 59 home games at Olympic Stadium in each of their final two seasons of 2003 and 2004; the franchise moved south to Washington, D.C. for the 2005 season and became the Washington Nationals.

Olympic Stadium's first baseball game was played on April 15, 1977. In front of 57,592, the Expos lost 7–2 to the Philadelphia Phillies. However, the Expos had to use a hacksaw to cut open the locks because the OIB did not have a master key.[7] The Expos played five home playoff games in 1981; two in the NLDS against the Phillies, and three in the NLCS against the Los Angeles Dodgers, who went on to win the World Series. On October 19, the Expos lost the decisive fifth game, 2–1, to the Dodgers on Rick Monday's ninth-inning home run. In 1982, the Major League Baseball All-Star Game was played at Olympic Stadium in front of 59,057—a stadium record for baseball. On September 29, 2004, the Expos played their last game in Montreal, losing 9–1 to the Florida Marlins before 31,395.[48]

Olympic Stadium proved to be somewhat problematic as a baseball venue. As in all multipurpose stadiums, the lower seating tier was set further back than in baseball-specific parks to accommodate the football field. However, since Canadian football fields are longer and wider than American football fields, Olympic Stadium's lower tier was set back even further than comparable seats at American multipurpose stadiums.[49] The upper deck was one of the highest in the majors; as was the case with most of its multipurpose counterparts, most of the upper-deck seats, particularly those in the outfield, were too far away to be of any use during the regular season.

The Expos felt considerable chagrin that they were not consulted on the stadium's location, design, or construction even though they were slated to be its primary tenants. Nonetheless, for most of their tenure they put considerable effort into making the atmosphere friendlier for baseball. During the 1970s and early 1980s, fans arriving at the stadium from the Metro were greeted by an oom-pah band playing "The Happy Wanderer." Whenever an opposing pitcher tried to hold a runner at first rather than pitch, the sound system would cluck at him like a chicken.[8]

Before the 1991 season, the OIB began a major overhaul on the stadium's baseball configuration. The lower deck in center field was removed to make room for a larger scoreboard with replay capability.[50] That scoreboard was installed ahead of the 1992 season. Also ahead of the 1992 season, the running track was removed, home plate was moved closer to the stands and new seats closer to the field were installed. Several distant sections of permanent seating beyond the outfield fence were closed, replaced with bleacher seats directly behind the fence. The total seating capacity for baseball was reduced from a high of around 60,400 to 46,000.

The Expos were very successful in the stadium for a time, with above National League median attendance in 1977 and from 1979 to 1983. The Expos outdrew the New York Mets from 1977 to 1983, and 1994 to 1996, as well as the New York Yankees in 1982 and 1983.[51][52][53]

The stadium's playing conditions left much to be desired. For most of the Expos' tenure, the playing surface was an extremely thin AstroTurf carpet, with only equally thin padding between it and the concrete floor. It was so hard on players' knees that visiting teams frequently ran at a nearby park. Longtime Expos trainer Ron McClain begged for a replacement, but the OIB was unwilling to spend the $1 million needed for a new surface. Before the roof finally arrived, players had to contend with huge patches of ice in early April or late September. Additionally, for most of the Expos' tenure, the padding on the fence was so thin that fielders risked severe injury by going after long fly balls. However, the OIB was also unwilling to replace the padding. By the 1990s, several free agents specifically demanded that the Expos be taken out of consideration due to the poor playing conditions.[8]

By the mid-1990s, owner Claude Brochu concluded that Olympic Stadium was not suitable as a baseball venue, and actively campaigned for a replacement.[8] Brochu sold the team to Jeffrey Loria in 2000, who was equally dissatisfied with Olympic Stadium; he bluntly stated, "We cannot stay here." However, Quebec Premier Lucien Bouchard refused to authorize public funding deemed necessary for a replacement, in part because Olympic Stadium still had not been paid for.[54] The poor conditions played a role in the Expos nearly being disbanded in the 2001 Major League Baseball contraction plan, which fell through due to court rulings.[8]

Ten years after the last Expos game at Olympic Stadium, the Toronto Blue Jays played two spring training games at the stadium against the New York Mets on March 28 and 29, 2014, with combined attendance of 96,350.[55] The Jays have continued this practice in subsequent years, against the Cincinnati Reds on April 3 and 4, 2015, with combined attendance of 96,545,[56][57] the Boston Red Sox on April 1 and 2, 2016, with combined attendance of 106,102,[58][59] the Pittsburgh Pirates on March 31 and April 1, 2017, combined attendance of 95,382,[60][61] the St. Louis Cardinals on March 26 and 27, 2018, with combined attendance of 51,151[62] and the Milwaukee Brewers on March 25 and 26, 2019. The New York Yankees were scheduled to play there on March 23 and 24, 2020 but the games were cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Longest home runs

Willie Stargell of the Pittsburgh Pirates hit the longest home run at Olympic Stadium on May 20, 1978, driving the ball into the second deck in right field for an estimated distance of 535 feet. The yellow seat that marked the location where the ball landed has been removed from the 300 level. The seat is now preserved at the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. Stargell also hit a notable home run at the Expos' original Montreal home, Jarry Park, which landed in a swimming pool beyond the right field fence.[63]

On April 4, 1988, the Expos' Opening Day, Darryl Strawberry of the New York Mets hit a ball off a speaker which hangs off a concrete ring at Olympic Stadium, estimated to have traveled 525 feet.

"Oh Henry" Rodríguez hit a ball on June 15, 1997, that bounced off the concrete ring in right field, caromed up to hit the roof, and came down, hitting a speaker. The distance traveled by this ball is also estimated at 525 feet.

The longest home run hit to left field was Vladimir Guerrero's blast on July 28, 2003, that hit an advertising sign directly below the left field upper deck. The ad was later replaced with a sign reading "VLAD 502".[64]

Soccer

The Olympic Stadium was the home of the NASL's Montreal Manic soccer team from 1981 to 1983. A 1981 playoff game against the Chicago Sting attracted a crowd of over 58,000. Several games of the 2007 FIFA Under 20 World Cup were played at Olympic Stadium and drew the largest crowds of the tournament, including two sell-outs of 55,800.

Olympic Stadium hosted a CONCACAF Champions League quarter-final game pitting the original Montreal Impact – who played primarily in the adjacent Saputo Stadium – against Club Santos Laguna of the Liga MX (Mexico First Division) on February 25, 2009. This was the first time an international soccer game took place in Montreal during the winter months.[65] The Impact won 2–0 in front of a record crowd of 55,571.[66] The stadium was also home to a friendly match between the Impact and A.C. Milan of the Italian Serie A on June 2, 2010 before 47,861.[67]

On July 25, 2009, Olympic Stadium became the first stadium outside France to host Ligue 1's Trophée des Champions, a super cup played by the winner of Ligue 1 and the Coupe de France. Over 34,000 attended the game. Bordeaux defeated Guingamp, 2–0. The game was held in Montreal to help Ligue 1 break into the growing North America soccer market.[68]

On March 17, 2012, a record crowd of 58,912 packed Olympic Stadium to cheer on the current version of the Montreal Impact for their MLS debut on home soil, in an entertaining 1–1 draw with the Chicago Fire, setting a new attendance record for professional soccer in Quebec.[69] That record was later broken on May 12, 2012 with 60,860 people for a match against the LA Galaxy, also setting a new attendance record for professional soccer in Canada.[70]

On August 24, 2014, the Olympic Stadium hosted the final match of the 2014 FIFA U-20 Women's World Cup.[71]

On April 29, 2015, a record crowd of 61,004 attended the final match of the CONCACAF Champions League between the Montreal Impact and Club América, establishing a new record attendance for professional soccer in Canada.[72]

The Olympic Stadium hosted tournament matches for the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup along with other stadiums across Canada.[73] One notable game was the semi-final match-up between the United States and Germany that took place on June 30, 2015, which drew a crowd of 51,176 people. The Americans won 2–0 in front of a largely partisan crowd and then went on to win their record third FIFA Women's World Cup trophy the following Sunday in Vancouver. This stadium is one of Canada's three candidate venues for the 2026 FIFA World Cup and is expected to get a retractable roof during the renovations for this sports event.[74]

Office space

Starting in 2018, the Desjardins Group plans to move approximately 1000 of its employees into the Montreal Tower. The company plans to occupy 7 of the 12 floors available in the tower. It is estimated that around $60 million in renovations are required before Desjardins can move in.[75]

Other

Olympic Stadium hosted the 1978 World Junior Speed Skating Championships where they crowned the American siblings Eric and Beth Heiden as junior world champions.[76]

In August 1979 the Olympic Stadium hosted the 1979 IAAF World Cup in Athletics.[77]

The Catholic Charismatic Renewal Assembly took place in the presence of Father Emiliano Tardif in 1979.

On June 20, 1980, Roberto Durán defeated Sugar Ray Leonard to win the WBC boxing world's welterweight championship at the Olympic Stadium.[78]

The Drum Corps International World Championship finals were held at this arena in 1981 and 1982.[79]

On September 11, 1984, Pope John Paul II participated in a youth rally with about 55,000 people in attendance.[80]

On October 30, 2010, a special mass, to commemorate the ascension to sainthood of Brother André, was held at the stadium. Over 30,000 people attended.[81]

In 2017, the venue was the site of the 2017 Artistic Gymnastics World Championships.[82]

Attendance record

Pink Floyd attracted the largest paid crowd to the Olympic Stadium: 78,322 people on July 6, 1977. The second-largest crowd was 73,898 for Emerson, Lake & Palmer on August 26, 1977. The largest crowds for an opera performance were on June 16 and 18, 1988, with 63,000 to watch a production of Aida.[83]

Transit

The stadium is directly connected to the Pie-IX metro station on the Green Line of the Montreal Metro. Viau metro station on the Green Line is also nearby.

Facts and figures

- At 165 m (541 ft), the Olympic Stadium is the world's tallest inclined structure.[84]

- Well over its original budget, the stadium ended up costing $770 million to construct. By 2006, the final cost had risen to $1.47 billion when calculating in repairs, modifications and interest paid out. It took 30 years to finally pay off the cost, leading to its nickname of "The Big Owe" (a play on "The Big O").[85]

- The roof is only 52 m (170.6 ft) above the field of play. As a result, a number of pop-ups and long home runs hit the roof over the years, necessitating the painting of orange lines on the roof to separate foul balls from fair balls.

- During their years playing in Olympic Stadium the Expos were one of only two teams not to employ the traditional yellow-painted foul poles with the New York Mets being the other; Olympic's poles were painted red while the Mets' home, Shea Stadium (and later Citi Field), used orange poles.

- The Olympic Stadium holds the record for a soccer game attendance in Canada. At the 1976 Summer Olympics soccer final, 72,000 people witnessed East Germany's 3–1 win over Poland.

- A yellow seat on the 300 level commemorated a 534-foot (163 m) home run by Willie Stargell of the Pittsburgh Pirates. It has since been moved to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame.

- The Montreal games of the 2007 FIFA U-20 World Cup were held at Olympic Stadium on a removable Team Pro EF RD surface that was purchased specifically for the tournament.[86]

- For the first time since the Olympic Games in 1976, a natural grass field was installed in the stadium for the Montreal Impact match versus A.C. Milan on June 2, 2010.[87]

- The stadium features a 101,600-watt public address system[88]

- The main room of the stadium is the largest in Quebec, at 43,504 m2 (468,270 sq ft)[89]

Commemorations

As part of the commemorative stamps created for the 1976 Olympics, Canada Post issued a stamp depicting the Olympic Stadium and Velodrome.[90]

See also

- List of Canadian Football League stadiums

- List of Major League Baseball stadiums (Former stadiums / ballparks)

- Olympic Stadium

- List of tallest buildings and structures in the world

References

- "The Stadium". Part olympique. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- MLB commissioner says Montreal needs a firm commitment for new stadium. theglobeandmail.com. April 1, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2015

- "Approximately 2,000 additional tickets on sale at noon". Montreal Impact. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- Stamps spoil party in Montreal with big 'W' at 'Big O' Archived October 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. cfl.ca. Retrieved April 28, 2015

- "Big O architect to do roof study". Montreal Gazette. June 10, 1981. p. 1.

- CBC News (December 19, 2006). "Quebec's Big Owe stadium debt is over". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on January 3, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2008.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Costello, Rory. Olympic Stadium (Montreal). Society for American Baseball Research, 2013.

- Keri, Jonah (2014). Up, Up and Away. Toronto: Random House Canada. ISBN 9780307361356.

- Chris Glenn (November 30, 2011). "Yokkaichi's Platypus Pavilion | Mie | Japan Tourist, by Chris Glenn". En.japantourist.jp. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- 1976 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 2. pp. 42–65.

- Rémillard, 196.

- Bauch, Hubert (September 14, 2000). "Taillibert: blame Ottawa, Quebec". The Montreal Gazette. Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- Peritz, Ingrid (January 17, 2009). "Montreal's billion-dollar 'Big Owe': What went wrong in '76?". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved January 19, 2009.

- "Building big: Databank: Olympic Stadium". WGBH. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- Egan, Andrew. "In Depth: World's Most Expensive Stadiums". Forbes.

- "Rio.intercollab.com". Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "Retrosheet Boxscore: Montreal Expos 10, San Diego Padres 1 (1)". Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- "ESPN.com: MLB – Merron: What a disaster!". Static.espn.go.com. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- Drolet, Daniel (January 24, 1985). "At last: Big O to get a retractable roof". Montreal Gazette. p. A-1.

- "Olympic Stadium roof in place after 11 years". Lawrence (KS) Journal World. Associated Press. April 15, 1987. p. 5B.

- "Storm rips Olympic Stadium roof". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. June 28, 1991. p. 20.

- Meyer, Paul (June 29, 1991). "Olympic Stadium roof damaged and retracted". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 18.

- "Snow causes roof to cave in at Olympic Stadium". Eugene Register-Guard. wire services. January 19, 1999. p. 5D.

- "Olympic Stadium out for month". Boca Raton News. Associated Press. January 20, 1999. p. 4B.

- Canwest News Service (October 2, 2008). "Impact begin search for location for winter game". Montreal Gazette.

- "Olympic stadium suing U.S. roofers". CBC News. November 10, 2000. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- Parker, Dave (January 28, 1999). "Dome supplier faces Montreal compensation battle". New Civil Engineer. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- La Presse, Actualites, Samedi 13 Fevrier 2010, p. A9

- Todd, Jack (July 6, 2016). "The 40-year hangover: how the 1976 Olympics nearly broke Montreal". Retrieved March 2, 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- Rushdi, Farid. "How Jeffrey Loria Destroyed The Montreal Expos / Washington Nationals". Bleacher Report. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- Riga, Andrew (January 9, 2009). "It's a go for the Big O (if there's no snow)". Montreal Gazette. Canwest. Retrieved January 9, 2009.

- CBC News (June 29, 2010). "Olympic Stadium to get $300M roof". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- Montreal Gazette (May 8, 2011). "Committee formed to study future of Montreal's Olympic Stadium". Postmedia Network Inc.

- Montreal Gazette (May 10, 2011). "Elephant in the room; Regie's committee on Big O a good start but leaves questions unanswered". Postmedia Network Inc. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- "Giant concrete slab falls at Montreal's Olympic Stadium". CTV News. The Canadian Press. March 5, 2012. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- Gentile, Davide (May 4, 2017). "Olympic Stadium roof deteriorating at rapid rate". CBC. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- Lowrie, Margan (July 12, 2016). "Forty years on, Montreal's Olympic Stadium remembered as more than just a money pit". National Post.

- "Montreal's Olympic Stadium – Solotech". MKTSOL. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- "Quebec OKs new roof for Big O". CBC News. November 9, 2017. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- Shingler, Benjamin (November 10, 2017). "Dismantling Montreal's Olympic Stadium would be 'foolish,' says man in charge". CBC. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- Lampert, Allison (December 7, 2013). "WHAT TO DO WITH THE BIG O?". Montreal Gazette. Montreal Gazette. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- CBC News (March 9, 2009). "Molson Stadium to begin $29.4M expansion". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- "Fan Fuel: Top 10 Grey Cup moments - Sportsnet.ca". Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- Gouvernement du Québec (2004). "About the Olympic Park – Facts and figures". La Régie des installations olympiques. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved November 22, 2008.

- "Sacramento Surge vs. Orlando Thunder. World Bowl II. June 6, 1992 • Fun While It Lasted". Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- Eskenazi, Gerald (July 29, 1988). "N.F.L.; Quebec Welcomes a Taste of the N.F.L." New York Times. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- "Oh, Canada: Jets vs. Bills". New York Daily News. December 3, 2009. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- "The Expos' last home game: An oral history – Sportsnet.ca". Sportsnet.ca. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- "ESPN.com – Page2 – The List: Worst ballparks". Espn.go.com. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- Clem's Baseball Blog entry on Olympic Stadium

- Sports Reference (2008). "Washington Nationals Attendance, Stadiums and Park Factors". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- Sports Reference (2008). "New York Mets Attendance, Stadiums and Park Factors". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- Sports Reference (2008). "New York Yankees Attendance, Stadiums and Park Factors". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- Smith, Curt (2001). Storied Stadiums. New York City: Carroll & Company. ISBN 0-7867-1187-6.

- "Cabrera's home run in the eighth gives Jays win over Mets". Tsn.ca. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- Mark Byrnes. "The Downtown Stadium That Could Have Saved the Montreal Expos". CityLab. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- "96,000 fans show their love of baseball at Blue Jays games in Montreal". Macleans.ca. The Canadian Press. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- "Red Sox top Blue Jays to sweep two-game Montreal series". Sportsnet.ca. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- "Blue Jays to face Red Sox in Montreal next spring". Sportsnet.ca. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- "Blue Jays tab starters for upcoming Montreal series". March 27, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "Blue Jays end pre-season with win in Montreal". Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "Cardinals use three-run eighth inning to beat Blue Jays at Olympic Stadium". The Globe And Mail. March 26, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- Ballpark Digest. "Jarry Park / Montreal Expos / 1969–1976". Ballpark Digest. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Montreal Expos (2004). Expos Media Guide 2004.

- "News". Montrealimpact.com. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- Farrell, Sean (February 25, 2009). "Big Montreal crowd takes in winter soccer". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- "Guess who's coming to town?". The Offside. April 14, 2010. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - profil Se déconnecter. "Le trophée des champions à Montréal". RDS.ca. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- "Recap: Record crowd sees Impact tie Fire in home debut". mlssoccer.com. March 17, 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- "Galaxy tie Impact before record crowd". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. June 18, 2012.

- "FIFA U-20 Women's World Cup: Matches – Knockout stage". FIFA.com. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- "Champions League: Montreal Impact sell 2,000 more tickets to final, setting new Canadian record". MLSsoccer.com. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- "FIFA Women's World Cup: Destination – Host Cities". FIFA.com. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- "Olympic Stadium will have a retractable roof in time for 2026 World Cup". Montréal Gazette. June 15, 2018.

- Lau, Rachel. "Desjardins to move into Montreal Olympic Stadium tower". Global News. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- Phillips, Randy (February 6, 1978). "Eric, Beth not Heiden in Junior speed skating". The Gazette. Montreal. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- "2nd IAAF World Cup in Athletics". IAAF.org. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

Montréal (Olympic Stadium), CANADA 24 AUG 1979 - 26 AUG 1979

- "June 20, 1980 in Sport". On This Day. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

Panamanian boxer Roberto Durán takes WBC welterweight title from Sugar Ray Leonard at Olympic Stadium in Montreal by unanimous points decision

-

- Boo, Michael (November 10, 2014). "Spotlight of the Week: 1981 Sky Ryders". Drum Corps International.

Drum Corps International held its 10th World Championship Finals in 1981 at Olympic Stadium in Montreal

- Boo, Michael (November 29, 2016). "Spotlight of the Week: 1982 Blue Devils". Drum Corps International.

the return of the Drum Corps International World Championships to Montreal in 1982 saw the Finals competition once again on television

- Boo, Michael (November 10, 2014). "Spotlight of the Week: 1981 Sky Ryders". Drum Corps International.

- "The Pope in Canada: A Journey Into the Heart". Americancatholic.org. Archived from the original on June 20, 2010. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- Anne Sutherland, Montreal Gazette: Monday, November 1, 2010 (November 1, 2010). "30,000 faithful flock to Olympic Stadium for Brother Andre celebration". Globaltvedmonton.com. Retrieved March 2, 2011.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Montreal Confirmed Host For 2017 Artistic World Championships". FloGymnastics. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- "LE STADE OLYMPIQUE" (PDF). Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "The Montréal Tower". Archived from the original on May 17, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- Merron, Jeff (April 22, 2003). "Montreal's house of horrors". ESPN.com. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Montreal Gazette (May 1, 2007). "New rug for Olympic Stadium". Canwest Publishing. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- Phillips, Randy (May 29, 2010). "Grass is greener on the inside". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- "RIO – Parc olympique de Montréal :: Salles au Stade olympique :: Location de salles au Stade olympique". Rio.gouv.qc.ca. Archived from the original on February 27, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- "RIO – Montreal Olympic Park :: Frequently Asked Questions". Rio.gouv.qc.ca. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- John Burnett. "Canadian Stamps Marked Montreal Olympics". Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

Sources

- Rémillard, François. Montreal architecture: A Guide to Styles and Buildings. Montreal: Meridian Press, 1990.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olympic Stadium (Montreal). |

- Official website – Parc Olympique Quebec

- Official Website – Montreal Tower

- Ballparks.com: Olympic Stadium

- Football Ballparks.com

- Baseball-Reference – annual Expos attendance and park factors

- history and notable events Baseball Library

- Olympic Stadium disaster timeline

Multimedia

- CBC Archives – Clip from 1975 – Stadium architect talks about his design

- CBC Archives – A look back on the history of the stadium (1999)

- CBC Archives – Discussion of building a tower for Montreal

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Olympiastadion Munich |

Summer Olympics Opening and Closing Ceremonies (Olympic Stadium) 1976 |

Succeeded by Grand Arena Moscow |

| Preceded by Olympiastadion Munich |

Olympic Athletics competitions Main Venue 1976 |

Succeeded by Grand Arena Moscow |

| Preceded by Olympiastadion Munich |

Summer Olympics Football Men's Finals (Olympic Stadium) 1976 |

Succeeded by Grand Arena Moscow |

| Preceded by Autostade Memorial Stadium Percival Molson Stadium |

Home of the Montreal Alouettes 1976–1986 1996–1997 2001 – current (with Percival Molson Stadium) |

Succeeded by Franchise folded Percival Molson Stadium current home (part time) |

| Preceded by Jarry Park Stadium |

Home of the Montreal Expos 1977–2004 |

Succeeded by RFK Stadium (as Washington Nationals) |

| Preceded by Eisstadion Inzell |

Host of the World Junior Speed Skating Championships 1978 |

Succeeded by L'Anneau de Vitesse |

| Preceded by Cleveland Stadium |

Host of the Major League Baseball All-Star Game 1982 |

Succeeded by Comiskey Park |

| Preceded by Legion Field |

Host of the Drum Corps International World Championship 1981–1982 |

Succeeded by Miami Orange Bowl |

| Preceded by National Olympic Stadium Tokyo |

FIFA U-20 Women's World Cup Final Venue 2014 |

Succeeded by National Football Stadium Port Moresby |