Grand Trunk Pacific Railway

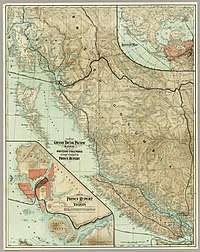

The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (reporting mark GTP) was a historic Canadian transcontinental railway running from Winnipeg to Prince Rupert, British Columbia, a Pacific coast port. East of Winnipeg the line continued as the National Transcontinental Railway (NTR], running across northern Ontario and Quebec, crossing the St. Lawrence River at Quebec City and ending at Moncton, New Brunswick. The Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) managed and operated the entire line.

| |

| |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Reporting mark | GTP |

| Locale | Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia |

| Dates of operation | 1914–1919 |

| Successor | Canadian National Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

Largely constructed 1907–14, the GTPR operated 1914–19, prior to nationalization as the Canadian National Railway (CNR). Despite poor decision-making by the various levels of government and the railway management, the GTPR established local employment opportunities, a telegraph service, and freight, passenger and mail transportation.[1]

History

Proposal

After the ouster of Edward Watkin, the GTR declined in 1870, then 1880, to build Canada's first transcontinental railway.[2] Subsequently, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) transcontinental and its feeder routes operated closer to the Canada–US border. Seeking a transcontinental to open up the central latitudes, the Government of Canada made overtures to the GTR and Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR). Both these regional operators in eastern[3] and central Canada initially declined, because projected traffic volumes suggested unlikely profitability.[4] Realizing expansion was essential, the GTR attempted to acquire the CNoR rather than collaborate on construction.[5] The GTR finally negotiated to construct only the western section, while the federal government would build the eastern sections as the NTR.[6] The respective legislation passed in 1903.[7]

Nearer to Asia than Vancouver, Port Simpson[8] was located about 19 miles (30.6 km) southeast of the southern entrance to the Portland Canal (which forms part of the boundary between British Columbia and Alaska). In 1903, when friction arose in Canada over the Alaska boundary decision favouring US interests, US President Theodore Roosevelt threatened to send an occupation force to nearby territory. In response, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier preferred a more southerly location for the terminal, which became the more easily defendable Kaien Island (Prince Rupert).[9][10]

Construction

Overview

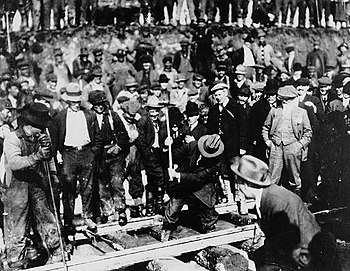

During the official ceremony on September 11, 1905 at Fort William, Ontario, Prime Minister Laurier turned the first sod for the construction of the GTPR, though the actual first sod occurred the previous month about 12 miles (19.3 km) south of Carberry, Manitoba.[11] From the former, the GTPR built a 190-mile (310 km) section of track, connecting with the NTR near Sioux Lookout. The route paralleled the CPR for 135 miles (217 km) west of Winnipeg, before veering northwest.[11] Beginning the year that the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan were established, the line proceeded west to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan in 1907, Edmonton, Alberta in 1909, and Wolf Creek in 1910.[12] For contractual purposes, Winnipeg to Wolf Creek (Edson, Alberta) was the Prairie Section, and Wolf Creek to the Pacific was the Mountain Section.[13] Foley, Welch and Stewart (FW&S) was selected as the prime contractor for the latter.[14]

The GTPR followed the original Sandford Fleming "Canadian Pacific Survey" route from Jasper, Alberta through the Yellowhead Pass,[14] and the track-laying machine crossed the BC/Alberta border in November 1911.[15] In the mountain region, costs escalated to $105,000 per mile, compared with the budgeted $60,000.[16] Following the CNoR paralleling through the Rockies, which created 108.4 miles (174.5 km) of duplication, the GTPR rail bed largely became redundant.[17][18] The more northerly Pine Pass option, as specified in its charter, may have been a better choice in terms of developing traffic, and in improving the current CNR network (especially if the later Pacific Great Eastern Railway route had opted for the Monkman Pass crossing). To secure concessions from the BC provincial government, eastward construction from the Pacific Coast began in 1907.[19] The track east of Prince Rupert reached 50 miles,[20] then 102 miles by 1910,[21] the Bulkley Valley in 1912 and Burns Lake in 1913.[22] The line completed across the prairies, through the Rockies, and to the newly constructed seaport at Prince Rupert, the last spike ceremony occurred one mile east of Fort Fraser, British Columbia at Stuart (Finmoore) on April 7, 1914.[23][24] Coming to pass, a 1910 prediction claimed if a line were built from Tête Jaune Cache to Vancouver, it would effectively kill Prince Rupert and relegate its route to branch line status.[25]

Construction crews

Claiming labour shortages, the GTP was unsuccessful in obtaining government approval to bring in unskilled immigrants from Asia.[26] By late 1912, 6,000 men were employed east of Edmonton.[27] Although contractors prohibited liquor in camps, bootlegging was rampant.[28] FW&S provided hospitals and medical services, charging employees one dollar per month.[29] The articles for the Grand Canyon of the Fraser, Dome Creek, McGregor, Upper Fraser, and the BC communities within the Category:Grand Trunk Pacific Railway stations, outline construction through those specific localities.

Flat-bottomed sternwheelers

FW&S operated five steamboats to supply their camps advancing east from Prince Rupert on the Skeena River. Launched in 1908, the Distributor and Skeena remained until 1914, as did the Omineca, purchased in 1908. Launched in 1909, the Operator and Conveyor were disassembled in 1911, transported to Tête Jaune and relaunched in 1912 on the Fraser River.[30][31][32] Detailed articles cover the sternwheelers Skeena, Operator, and Conveyor and their roles on the Skeena River, and on the Fraser River.

Fraser River scows

During the construction phase from Tête Jaune to Fort George thousands of tons of freight, both for railway construction and merchants, travelled downstream from the railhead by scow.[33][34] In 1913, when scowing on this part of the river peaked, about 1,500 men were employed as scowmen, or "River Hogs" as they were generally called. In high water, the trip from Tête Jaune took five days and in low water up to 12 days, because of the shallow bars. Each vessel measured about 40 feet long and 12–16 feet wide and carried 20–30 tons. Two men crewed each end. The Goat River Rapids, Grand Canyon, and Giscome Rapids, were extremely dangerous, with wrecks and drownings common. Dismantlers purchased the scows that survived the journey, selling the used lumber primarily for house building.[35]

Real estate development

The funding for railway expansion depended upon returns from the sale of land acquired by the railway. The Grand Trunk Pacific Town & Development Co. was responsible for locating and promoting strategic town sites.[36] However, the priority of maximising profit undermined the economic prosperity of communities and other businesses, hampering the increase in traffic volumes essential for the GTP’s own survival.[37] In 1910 at Prince Rupert, although 25 real estate agents operated, David Hayes, brother of GTP president Charles Melville Hays was the sole company agent.[38] In what would become Prince George, the company purchased the First Nations reserve for a railway yard and a new town site.[39] The GTPR also caused the displacement and socio-economic destruction of native communities along the route, many of whom had social and economic values in conflict with those of the railway.[40]

Steamships

Beginning in 1910, a GTPR steamship service operated from Prince Rupert. The first ship, the SS Prince Albert (formerly the Bruno built in 1892 at Hull, England), was an 84-ton, steel-hulled vessel and travelled as far as Vancouver and Victoria. Next, the SS Prince John (formerly the Amethyst built in England in 1910), travelled to the Queen Charlotte Islands. Built in 1910, the much larger SS Prince George and SS Prince Rupert, both 3,380-ton, 18-knot vessels, could carry 1,500 passengers with staterooms for 220. These ships operated a weekly service from Seattle to Victoria, Vancouver, Prince Rupert and Anyox.[41]

The vision was for coastal shipping to mature into a trans-Pacific line.[42] However, Prime Minister Robert Borden was disinterested in promoting Prince Rupert as a port of call for any shipping lines. While Vancouver flourished, Prince Rupert languished.[43] From 1919, the Canadian Government Merchant Marine (CGMM)[44] in partnership with CNR promoted the development of import/export trade with Pacific rim countries. Although this expansion benefitted Vancouver,[45] Prince Rupert remained a backwater.

Ancillary facilities

The GTPR built the Fort Garry Hotel in Winnipeg, and the Hotel Macdonald in Edmonton. Halibird and Roche of Chicago designed the hotel for Prince George, but it never left the drawing-board stage. Construction of the $2m Chateau Prince Rupert, designed by Francis Rattenbury, did not proceed beyond the foundations laid in 1910. Its forerunner, the temporary GTP Inn, was demolished in 1962. Sometimes in conjunction with the CNoR, the GTPR built some impressive city stations.[46][47][48][49]

When built in 1910, the Grand Trunk Pacific dock in Seattle was the largest on the west coast. On July 30, 1914, fire destroyed the facility. The federal government provided a $2m subsidy for a dry dock at Prince Rupert capable of handling ships up to 20,000 tons. Completed in 1915, it catered for only much smaller local vessels prior to World War II. It was dismantled during 1954/55.[50][51][52]

Operations

The CNoR tracklaying through the Canadian Rockies in 1913 roughly paralleled the GTPR line of 1911, creating about 100 miles of duplication. In 1917, a contingent from the Corps of Canadian Railway Troops added several crossovers to amalgamate the tracks into a single line along the preferred grade as far west as Red Pass Junction (misidentifed as 36 miles west of Red Pass on Google Maps). The surplus rails were lifted and the heavier grade GTPR ones shipped to France for use during World War I.

In 1915, unable to meet its debts, the GTP asked the federal government to take over the GTPR.[46] The CNoR was in worse financial shape.[53][54] The royal commission that considered the issue during 1916, released its findings in 1917.[55] In March 1919, after the GTPR defaulted on construction loans to the federal government, the federal Department of Railways and Canals effectively took control of the GTPR,[56] before it merged into the CNR in July 1920. Noting not just numerous construction blunders, the 1921 arbitration on worth ranked its significance within the naïve railway schemes of that era by the observation, "It would be difficult to imagine a more misconceived project...".[57] The GTP itself was nationalized in 1922.[58]

Current status

Today, the majority of the GTPR is still in use as CN's (name change to Canadian National or acronym "CN" in 1960) main line from Winnipeg to Jasper. The former CNoR line, and a later connection to Tête Jaune Cache, merge north of Valemount, before continuing south to Vancouver. The former GTPR line through Tête Jaune Cache to Prince Rupert forms an important CN secondary main line. The GTPR's high construction standards,[59][60] and the fact Yellowhead Pass has the best gradients of any railway crossing of the Continental Divide in North America [59][61] gives the CN a competitive advantage in terms of fuel efficiency and the ability to haul tonnage.

After a century languishing far behind Vancouver, the Port of Prince Rupert has grown in importance since the early 2000s. Ongoing redevelopment of terminal infracture, less municipal congestion than other West Coast ports, proximity to the great circle route from East Asia to North America, and a fast connection to the Midwestern United States along the former GTPR route, have reduced transportation times.[62][63]

Footnotes

- Morrow 2010, pp. 107–108.

- MacKay 1986, pp. 40, 45 & 47.

- Morrow 2010, p. 13.

- Morrow 2010, p. 9.

- MacKay 1986, p. 64.

- MacKay 1986, pp. 63 & 66.

- MacKay 1986, p. 8.

- Morrow 2010, pp. 13–15.

- Hayes, Derek (1999), Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest, Vancouver: Cavendish Books, p. 190, ISBN 1-55289-900-4

- MacKay 1986, pp. 86 & 87.

- MacKay 1986, p. 71.

- MacKay 1986, p. 76.

- Morrow 2010, p. 23.

- Morrow 2010, p. 14.

- Fort George Herald, 23 Dec 1911

- MacKay 1986, pp. 101–102.

- Lower 1939, p. 195.

- "Map of duplicate track lifted 1917" (PDF). www.railwaystationlists.co.uk.

- Morrow 2010, pp. 16 & 23.

- Fort George Tribune, 6 Aug 1910

- Fort George Tribune, 31 Dec 1910

- MacKay 1986, p. 103.

- Morrow 2010, p. 24.

- MacKay 1986, p. 104.

- Fort George Herald, 17 Sep 1910

- Fort George Tribune, 25 Dec 1909

- Fort George Tribune, 16 Nov 1912

- Wheeler 1979, p. 121.

- Morrow 2010, p. 45.

- Fort George Herald, 6 Jan 1912

- Wheeler 1979, p. 107.

- Morrow 2010, p. 37.

- "Scow Boats, Heavy Haulers on the Athabasca River, Alberta, Canada". fhnas.ca.

- Morrow 2010, p. 40.

- Prince George Citizen, 26 May 1938

- Morrow 2010, pp. 26–28.

- Frank, Leonard (1996). A Thousand Blunders: The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and Northern British Columbia. UBC Press. pp. 274–277. ISBN 9780774805322.

- MacKay 1986, pp. 98–99.

- Morrow 2010, p. 26.

- McDonald, James A (1990). "Bleeding Day and Night: The Construction of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway Across Tsimshian Reserve Lands" (PDF). www3.brandonu.ca. Canadian Journal of Native Studies.

- "Old Time Trains". www.trainweb.org.

- MacKay 1986, p. 99–100.

- MacKay 1986, pp. 118–119.

- "CGMM 1919–28". www.theshipslist.com.

- MacKay 1986, pp. 122–127.

- MacKay 1986, p. 105.

- Rowse, Sue Harper (1 November 2005). "Birth of A City: Prince Rupert To 1914". www.books.google.ca. Self-published.

- Lower 1939, p. 127.

- Prince George Citizen, 6 Mar 1985 (41)

- "Prince Rupert Dry Dock". www.shipbuildinghistory.com.

- "Living Landscapes". royalbcmuseum.bc.ca.

- MacKay 1986, p. 99.

- Morrow 2010, pp. 98–101.

- Prince George Citizen, 20 Sep 2001

- MacKay 1986, p. 120.

- Prince George Citizen, 12 Mar 1919

- Lower 1939, p. 183.

- MacKay 1986, p. 121.

- MacKay 1986, pp. 74 & 102.

- Morrow 2010, pp. 98, 102–103.

- Morrow 2010, pp. 76–80.

- "Port of Prince Rupert Employment Surges, 31 Jul 2019". www.businessexaminer.ca.

- "Prince Rupert port receives $153.7m federal funding injection, 6 Sep 2019". www.nsnews.com.

References

- Lower, Joseph Arthur (1939). "The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and British Columbia". www.library.ubc.ca.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacKay, Donald (1986). The Asian Dream: The Pacific Rim and Canada's National Railway. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 0-88894-501-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morrow, Trelle A. (2010). The Grand Trunk Pacific and other Fort George stuff. CNC Press. ISBN 9780921087502.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wheeler, Marilyn J. (1979). The Robson Valley Story. McBride Robson Valley Story Group. ISBN 0969020902.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Prince George archival newspapers". www.pgpl.ca.

- Todd, John (September 1976). "The Grand Trunk Pacific's Lake Superior Branch" (PDF). Canadian Rail. Canadian Railroad Historical Association. 296. ISSN 0008-4875.

See also

- Jasper–Prince Rupert passenger service

- Defunct railroads of North America

- List of Grand Trunk Pacific Railway stations