Ottawa River

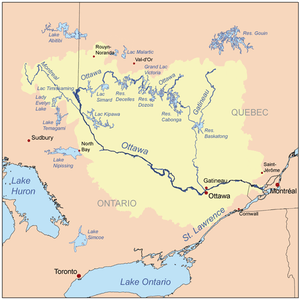

The Ottawa River (French: Rivière des Outaouais, Algonquin: Kitchissippi) is a river in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. It is named in honour of the Algonquin word 'to trade', as it was the major trade route of Eastern Canada at the time. For most of its length, it defines the border between these two provinces. It is a major tributary of the St. Lawrence River and the longest river in Quebec.

| Ottawa River | |

|---|---|

The Ottawa River in the autumn | |

Map of the Ottawa River drainage basin | |

| Location | |

| Country | Canada |

| Provinces | Quebec, Ontario |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Lac des Outaouais |

| • location | Lac-Moselle, La Vallée-de-la-Gatineau RCM, Outaouais, Quebec, Canada |

| • coordinates | 47°38′38″N 75°38′35″W |

| Mouth | St. Lawrence River |

• location | Montreal, Quebec and Ottawa, Ontario, Canada |

• coordinates | 45°27′N 74°05′W |

| Length | 1,271 km (790 mi) |

| Basin size | 146,300 km2 (56,500 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Carillon dam |

| • average | 1,950 m3/s (69,000 cu ft/s) |

| • minimum | 749 m3/s (26,500 cu ft/s) |

| • maximum | 5,351 m3/s (189,000 cu ft/s) |

Geography

The river rises at Lac des Outaouais, north of the Laurentian Mountains of central Quebec, and flows west to Lake Timiskaming. From there its route has been used to define the interprovincial border with Ontario. The river reaches great depths of nearly 460 feet in some places.

From Lake Timiskaming, the river flows southeast to Ottawa and Gatineau, where it tumbles over Chaudière Falls and further takes in the Rideau and Gatineau rivers.

The Ottawa River drains into the Lake of Two Mountains and the St. Lawrence River at Montreal. The river is 1,271 kilometres (790 mi) long; it drains an area of 146,300 square kilometres (56,500 sq mi), 65 percent in Quebec and the rest in Ontario, with a mean discharge of 1,950 cubic metres per second (69,000 cu ft/s).[2]

The average annual mean waterflow measured at Carillon dam, near the Lake of Two Mountains, is 1,939 cubic metres per second (68,500 cu ft/s), with average annual extremes of 749 to 5,351 cubic metres per second (26,500 to 189,000 cu ft/s). Record historic levels since 1964 are a low of 467 cubic metres per second (16,500 cu ft/s) in 2010 and a high of 9,094 cubic metres per second (321,200 cu ft/s) in 2017.[3]

The river flows through large areas of deciduous and coniferous forest formed over thousands of years as trees recolonized the Ottawa Valley after the ice age.[4] Generally, the coniferous forests and blueberry bogs occur on old sand plains left by retreating glaciers, or in wetter areas with clay substrate. The deciduous forests, dominated by birch, maple, beech, oak and ash occur in more mesic areas with better soil, generally around the boundary with the La Varendrye Park.[5][6] These primeval forests were occasionally affected by natural fire, mostly started by lightning, which led to increased reproduction by pine and oak, as well as fire barrens and their associated species.[7] The vast areas of pine were exploited by early loggers.[8] Later generations of logging removed hemlock for use in tanning leather, leaving a permanent deficit of hemlock in most forests.[9] Associated with the logging and early settlement were vast wild fires which not only removed the forests, but led to soil erosion.[10] Consequently, nearly all the forests show varying degrees of human disturbance. Tracts of older forest are uncommon, and hence they are considered of considerable importance for conservation.[11]

The Ottawa River has large areas of wetlands. Some of the more biologically important wetland areas include (going downstream from Pembroke), the Westmeath sand dune/wetland complex, Mississippi Snye, Breckenridge Nature Reserve, Shirleys Bay, Ottawa Beach/Andrew Haydon Park, Petrie Island, the Duck Islands[12] and Greens Creek.[13][14] The Westmeath sand dune/wetland complex is significant for its relatively pristine sand dunes, few of which remain along the Ottawa River, and the many associated rare plants. Shirleys Bay has a biologically diverse shoreline alvar, as well as one of the largest silver maple swamps along the river. Like all wetlands, these depend upon the seasonal fluctuations in the water level.[15] High water levels help create and maintain silver maple swamps,[16] while low water periods allow many rare wetland plants to grow on the emerged sand and clay flats.[17] There are five principal wetland vegetation types. One is swamp, mostly silver maple. There are four herbaceous vegetation types, named for the dominant plant species in them: Scirpus, Eleocharis, Sparganium and Typha.[18] Which type occurs in a particular location depends upon factors such as substrate type, water depth, ice-scour and fertility. Inland, and mostly south of the river, older river channels, which date back to the end of the ice age, and no longer have flowing water, have sometimes filled with a different wetland type, peat bog. Examples include Mer Bleue and Alfred Bog.[13]

Major tributaries include:

Communities along the Ottawa River include (in down-stream order):

- Kitcisakik, Quebec

- Moffet, Quebec

- Angliers, Quebec

- Notre-Dame-du-Nord, Quebec

- Temiskaming Shores, Ontario

- Ville-Marie, Quebec

- Témiscaming, Quebec

- Thorne, Ontario

- Mattawa, Ontario

- Deux Rivières, Ontario

- Rapides-des-Joachims, Quebec

- Laurentian Hills, Ontario

- Deep River, Ontario

- Sheenboro, Quebec

- Petawawa, Ontario

- Pembroke, Ontario

- Westmeath, Ontario

- Waltham, Quebec

- Fort-Coulonge, Quebec

- La Passe, Ontario

- Campbell's Bay, Quebec

- Portage-du-Fort, Quebec

- Bristol, Quebec

- McNab/Braeside, Ontario

- Arnprior, Ontario

- Quyon, Quebec

- Ottawa, Ontario

- Aylmer, Quebec

- Hull, Quebec

- Gatineau, Quebec

- Orléans, Ontario

- Masson-Angers, Quebec

- Clarence-Rockland, Ontario

- Thurso, Quebec

- Plaisance, Quebec

- Papineauville, Quebec

- Montebello, Quebec

- Fassett, Quebec

- L'Orignal, Ontario

- Grenville, Quebec

- Hawkesbury, Ontario

- Carillon, Quebec

- Saint-André-Est, Quebec

- Rigaud, Quebec

- Saint-Placide, Quebec

- Hudson, Quebec

- Oka, Quebec

- Vaudreuil-sur-le-Lac, Quebec

- Vaudreuil-Dorion, Quebec

- Pincourt, Quebec

- Norway Bay, Quebec

- Pointe-des-Cascades, Quebec

Geology

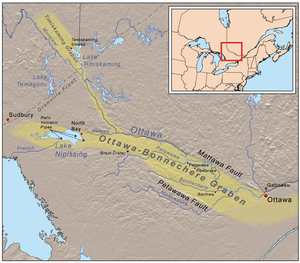

The Ottawa River lies in the Ottawa-Bonnechere Graben, which is a Mesozoic rift valley that formed 175 million years ago. Much of the river flows through the Canadian Shield, although lower areas flow through limestone plains and glacial deposits.[19]

As the glacial ice sheet began to retreat at the end of the last ice age, the Ottawa River valley, which, along with the St. Lawrence River valley and Lake Champlain, had been depressed to below sea level by the glacier's weight, filled with sea water.[20] The resulting arm of the ocean is known as the Champlain Sea. Fossil remains of marine life dating 12 to 10 thousand years ago have been found in marine clay throughout the region. Sand deposits from this era have produced vast plains, often dominated by pine forests, as well as localized areas of sand dunes, such as Westmeath and Constance Bay.[19] Clay deposits from this period have resulted in areas of poor drainage, large swamps, and peat bogs in some ancient channels of this river. Hence, the distribution of forests and wetlands is very much a product of these past glacial events.[6]

Large deposits of a material commonly known as Leda clay also formed. These deposits become highly unstable after heavy rains. Numerous landslides have occurred as a result. The former site of the town of Lemieux, Ontario collapsed into the South Nation River in 1993. The town's residents had previously been relocated because of the suspected instability of the earth in that location.

As the land gradually rose again the sea coast retreated and the fresh water courses of today took shape. Following the demise of the Champlain Sea the Ottawa River Valley continued to drain the waters of the emerging Upper Great Lakes basin through Lake Nipissing and the Mattawa River. Owing to the ongoing uplift of the land, the eastward flow became blocked around 4000 years ago. Thereafter Lake Nipissing drained westward, through the French River which later became a link in the historic canoe route to the West.[21]

History

As it does to this day, the river played a vital role in life of the Algonquin people, who lived throughout its watershed at contact. The river is called Kichisìpi, meaning "Great River" in Anicinàbemowin, the Algonquin language. The Algonquin define themselves in terms of their position on the river, referring to themselves as the Omàmiwinini, 'down-river people'. Although a majority of the Algonquin First Nation lives in Quebec, the entire Ottawa Valley is Algonquin traditional territory. Present settlement is a result of adaptations made as a result of settler pressures.[22]

Some early European explorers, possibly considering the Ottawa River to be more significant than the Upper St. Lawrence River, applied the name River Canada to the Ottawa River and the St. Lawrence River below the confluence at Montreal. As the extent of the Great Lakes became clear and the river began to be regarded as a tributary, it was variously known as the Grand River, "Great River" or Grand River of the Algonquins before the present name was settled upon. This name change resulted from the Ottawa peoples' control of the river circa 1685. However, only one band of Ottawa, the Kinouncherpirini or Keinouch, ever inhabited the Ottawa Valley.

In 1615, Samuel de Champlain and Étienne Brûlé, assisted by Algonquin guides, were the first Europeans to travel up the Ottawa River and follow the water route west along the Mattawa and French Rivers to the Great Lakes. See Canadian Canoe Routes (early). For the following two centuries, this route was used by French fur traders, voyageurs and coureurs des bois to Canada's interior. The river posed serious hazards to these travellers. The section near Deux Rivières used to have spectacular and wild rapids, namely the Rapide de la Veillée, the Trou, the Rapide des Deux Rivières, and the Rapide de la Roche Capitaine. In 1800, explorer Daniel Harmon reported 14 crosses marking the deaths of voyageurs who had drowned in the dangerous waters along this section of the Ottawa.[23]

The main trading posts along the river were: Lachine, Fort Coulonge, Lac des Allumettes, Mattawa House, where west-bound canoes left the river and Fort Témiscamingue. From Lake Timiskaming a portage led north to the Abitibi River and James Bay.

In the early 19th century, the Ottawa River and its tributaries were used to gain access to large virgin forests of white pine. A booming trade in timber developed, and large rafts of logs were floated down the river. A scattering of small subsistence farming communities developed along the shores of the river to provide manpower for the lumber camps in winter. In 1832, following the War of 1812, the Ottawa River gained strategic importance when the Carillon Canal was completed. Together with the Rideau Canal, the Carillon Canal was constructed to provide an alternate military supply route to Kingston and Lake Ontario, bypassing the route along the Saint Lawrence River.[24]

Power generation

A pulp and paper mill (at Témiscaming) and several hydroelectric dams have been constructed on the river. In 1950, the dam at Rapides-des-Joachims, was built, forming Holden Lake behind it and thereby submerging the rapids and portages at Deux Rivières.[23] These hydro dams have had negative effects upon shoreline and wetland ecosystems,[25] and are thought to also be responsible for the near extermination of American eels, which were once an abundant species in the river, but which are now uncommon.[26] As an economic route, its importance was eclipsed by railroad and highways in the 20th century. It is no longer used for log driving, however, it is still extensively used for recreational boating. Some 20,000 pleasure boaters visit the Carillon Canal annually.[24]

Today, Outaouais Herald Emeritus at the Canadian Heraldic Authority is named after the river.

Hydroelectric installations

Hydroelectric installations on the Upper Ottawa (in downstream order):

| Installation | Type | Generating cap. | Year built | Name of reservoir | Operator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bourque Dam | Dam | n/a | 1949 | Dozois Reservoir | Hydro-Québec |

| Rapide-7 | Generating station | 48 MW | 1941 / 1949 | Decelles Lake | Hydro-Québec |

| Rapide-2 | Run of river g.s. | 48 MW | 1954 | n/a | Hydro-Québec |

| Rapides-des-Quinze | Run of river g.s. | 95 MW | 1923 | n/a | Hydro-Québec |

| Rapides-des-Îles | Run of river g.s. | 147 MW | 1966 | n/a | Hydro-Québec |

| Première-Chute | Run of river g.s. | 130 MW | 1968 | n/a | Hydro-Québec |

Lower Ottawa (in downstream order):

| Installation | Type | Generating cap. | Year built | Name of reservoir | Operator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Otto Holden | Run of river g.s. | 243 MW | 1952 | n/a | Ontario Power Generation |

| Des Joachims | Run of river g.s. | 429 MW | 1950 | Holden Lake | Ontario Power Generation |

| Bryson | Run of river g.s. | 61 MW | 1925 | n/a | Hydro-Québec |

| Chenaux | Run of river g.s. | 144 MW | 1950 | n/a | Ontario Power Generation |

| Chute-des-Chats (Chats Falls) | Run of river g.s. | 185 MW | 1931 | Lac des Chats | Hydro-Québec and OPG * |

| Hull-2 | Run of river g.s. | 27 MW | 1920 | n/a | Hydro-Québec |

| Carillon | Run of river g.s. | 752 MW | 1962 | n/a | Hydro-Québec |

* Ontario Power Generation operates generators 2, 3, 4, and 5 with a capacity of 96 MW; and Hydro-Québec operates generators 6, 7, 8, and 9 with a capacity of 89 MW.

See also

References

- "Paleontological Highlights". OttawaRiverKeeper.ca. Archived from the original on June 24, 2009. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "Facts about Canada: Rivers". Natural Resources Canada/Atlas of Canada. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- "Monthly and Annual Mean Water Levels in Metres From 1950, Ottawa River at Carillon". Ottawa River Regulation Planning Board. Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- Anderson, T.W. 1989. Vegetation changes over 12000 years. Geos (3) 39-47.

- Braun, E.L. 1950. Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America. The Blakiston Co., Philadelphia, PA.

- Keddy, P.A. 2008. Earth, Water, Fire. An Ecological Profile of Lanark County. General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. (revised from first edition 1999).

- Catling, P. and V. Brownell. 1999. Pages 392-405 in the book Anderson, R.C., J.S. Fralish and J.M. Baskin. 1999. Savannas, Barrens, and Rock Outcrop Plant Communities of North America. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Hughson, J.W. and C.C. J. Bond. 1965. Hurling Down the Pine. The Historical Society of the Gatineau, Old Chelsea, Quebec. First edition 1964, Revised second edition 1965.

- Keddy, C.J. 1993. Forest History of Eastern Ontario. Prepared for the Eastern Ontario Model Forest Group, Kemptville

- Howe, C.D. 1915. The effect of repeated forest fires upon the reproduction of commercial species in Peterborough County, Ontario. Pages 116-211 in Forest Protection in Canada, 1913 1914, Commission of Conservation of Canada, William Briggs, Toronto.

- Henry, M. and P. Quinby. 2009. Ontario Old Growth Forests. Fitzhenry and Whiteside, Markham, Ontario

- Darbyshire, S.J. 1981. Upper Duck and Lower Duck Islands. Trail and Landscape 15:133-139.

- Brunton, D.F. 1992. Life Science Areas of Natural and Scientific Interest in Site District 6-12. A Review and Assessment of Significant Natural Areas. Report prepared for Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Kemptville, Ontario.

- Ecosystem Diversity Archived 2012-04-24 at the Wayback Machine. ottawariverkeeper.ca. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Toner, M, and P. Keddy. 1997. River hydrology and riparian wetlands: a predictive model for ecological assembly. Ecological Applications 7: 236-246

- Brunton, D.F. and B.M. Di Labio. Diversity and ecological characteristics of emergent beach flora along the Ottawa River in the Ottawa-Hull region, Quebec and Ontario. Naturaliste canadien 116: 179-191.

- Day, R., P.A. Keddy, J. McNeill and T. Carleton. 1988. Fertility and disturbance gradients: a summary model for riverine marsh vegetation. Ecology 69:1044-1054

- Chapman, L.J. and D.F. Putnam. 1984. The Physiography of Southern Ontario. Third edition. Ontario Geological Survey, Special Volume No.2. Government of Ontario, Toronto.

- "Champlain Sea: Phase 2". hannover.park.org. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- "Lake Nipissing". Ontario's Historical Plaques. Alan L Brown. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- "Algonquin Land Claim with Ontario". Ontario Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- Ontario Heritage Foundation, Ministry of Culture and Communications

- "Carillon Canal National Historic Site of Canada, Cultural Heritage". Parks Canada. Archived from the original on 2007-05-06. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.497 p.

- "COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the American Eel in Canada" (PDF). Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. pp. 45–46. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ottawa River. |