Hamilton, Ontario

Hamilton is a port city in the Canadian province of Ontario. An industrialized city in the Golden Horseshoe at the west end of Lake Ontario, Hamilton has a population of 536,917, and its census metropolitan area, which includes Burlington and Grimsby, has a population of 747,545. The city is 58 kilometres (36 mi) southwest of Toronto, with which the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) is formed.

Hamilton | |

|---|---|

City (single-tier) | |

| City of Hamilton | |

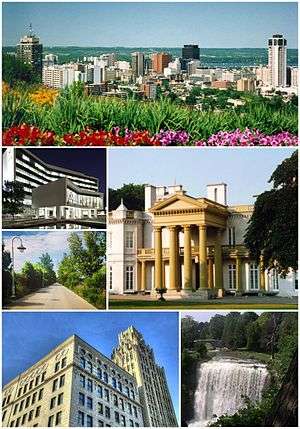

Counter clockwise from the top: View of Downtown Hamilton from Sam Lawrence Park, Hamilton City Hall, Bayfront Park Harbour Front Trail, Historic Art Deco and Gothic Revival Pigott Building complex, Webster's Falls, Dundurn Castle | |

Coat of arms | |

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto(s): "Together Aspire – Together Achieve" | |

Location in the province of Ontario, Canada | |

Hamilton Location of Hamilton in southern Ontario | |

| Coordinates: 43°15′24″N 79°52′09″W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

| Incorporated | June 9, 1846[4] |

| Named for | George Hamilton |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Fred Eisenberger |

| • City Council | Hamilton City Council |

| • MPs | List of MPs

|

| • MPPs | List of MPPs

|

| Area | |

| • City (single-tier) | 1,138.11 km2 (439.43 sq mi) |

| • Land | 1,117.11 km2 (431.32 sq mi) |

| • Water | 21 km2 (8 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 351.67 km2 (135.78 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,371.76 km2 (529.64 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 324 m (1,063 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 75 m (246 ft) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • City (single-tier) | 536,917 (10th) |

| • Density | 480.6/km2 (1,245/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 693,645 |

| • Metro | 763,445 (9th) |

| Demonym(s) | Hamiltonian |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Forward sortation area | L8E to L8W, L9A to L9C, L9G to L9H, L9K |

| Area codes | 226, 289, 519, 365 and 905 |

| Highways | |

| Website | www |

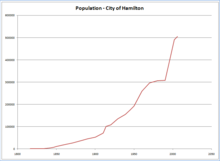

On January 1, 2001, the current boundaries of Hamilton were created through the amalgamation of the original city with other municipalities of the Regional Municipality of Hamilton–Wentworth.[7] Residents of the city are known as Hamiltonians.[8] Since 1981, the metropolitan area has been listed as the ninth largest in Canada and the 3rd largest in Ontario.

Hamilton is home to the Royal Botanical Gardens, the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum, the Bruce Trail, McMaster University, Redeemer University College and Mohawk College. McMaster University is ranked 4th in Canada and 77th in the world by Times Higher Education Rankings 2018–19.[9]

History

In pre-colonial times, the Neutral First Nation used much of the land but were gradually driven out by the Five (later Six) Nations (Iroquois) who were allied with the British against the Huron and their French allies. A member of the Iroquois Confederacy provided the route and name for Mohawk Road, which originally included King Street in the lower city.

Following the United States gaining independence after their American Revolutionary War, in 1784, about 10,000 United Empire Loyalists settled in Upper Canada (what is now southern Ontario), chiefly in Niagara, around the Bay of Quinte, and along the St. Lawrence River between Lake Ontario and Montreal. The Crown granted them land in these areas to develop Upper Canada and to compensate them for losses in the United States. With former First Nations lands available for purchase, these new settlers were soon followed by many more Americans, attracted by the availability of inexpensive, arable land. At the same time, large numbers of Iroquois who had allied with Britain arrived from the United States and were settled on reserves west of Lake Ontario as compensation for lands they lost in what was now the United States.[10] During the War of 1812, British regulars and Canadian militia defeated invading American troops at the Battle of Stoney Creek, fought in what is now a park in eastern Hamilton.

The town of Hamilton was conceived by George Hamilton (a son of a Queenston entrepreneur and founder, Robert Hamilton), when he purchased farm holdings of James Durand,[11] the local Member of the British Legislative Assembly, shortly after the War of 1812.[11] Nathaniel Hughson, a property owner to the north, cooperated with George Hamilton to prepare a proposal for a courthouse and jail on Hamilton's property. Hamilton offered the land to the crown for the future site. Durand was empowered by Hughson and Hamilton to sell property holdings which later became the site of the town. As he had been instructed, Durand circulated the offers at York during a session of the Legislative Assembly, which established a new Gore District, of which the Hamilton townsite was a member.[11]

Initially, this town was not the most important centre of the Gore District. An early indication of Hamilton's sudden prosperity occurred in 1816, when it was chosen over Ancaster, Ontario to be the new Gore District's administrative centre. Another dramatic economic turnabout for Hamilton occurred in 1832 when a canal was finally cut through the outer sand bar that enabled Hamilton to become a major port.[12] A permanent jail was not constructed until 1832, when a cut-stone design was completed on Prince's Square, one of the two squares created in 1816.[11] Subsequently, the first police board and the town limits were defined by statute on February 13, 1833.[13] Official city status was achieved on June 9, 1846, by an act of Parliament, 9 Victoria Chapter 73.[4]

By 1845, the population was 6,475. In 1846, there were useful roads to many communities as well as stagecoaches and steamboats to Toronto, Queenston, and Niagara. Eleven cargo schooners were owned in Hamilton. Eleven churches were in operation. A reading room provided access to newspapers from other cities and from England and the U.S. In addition to stores of all types, four banks, tradesmen of various types, and sixty-five taverns, industry in the community included three breweries, ten importers of dry goods and groceries, five importers of hardware, two tanneries, three coachmakers, and a marble and a stone works.[14]

As the city grew, several prominent buildings were constructed in the late 19th century, including the Grand Lodge of Canada in 1855,[15] West Flamboro Methodist Church in 1879 (later purchased by Dufferin Masonic Lodge in 1893),[16] a public library in 1890, and the Right House department store in 1893. The first commercial telephone service in Canada, the first telephone exchange in the British Empire, and the second telephone exchange in all of North America were each established in the city between 1877–78.[17] The city had several interurban electric street railways and two inclines, all powered by the Cataract Power Co.[18]

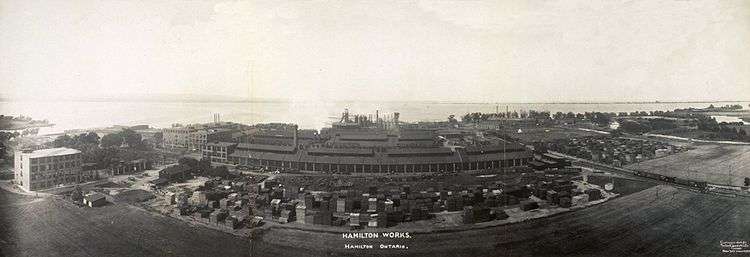

Though suffering through the Hamilton Street Railway strike of 1906, with industrial businesses expanding, Hamilton's population doubled between 1900 and 1914. Two steel manufacturing companies, Stelco and Dofasco, were formed in 1910 and 1912, respectively. Procter & Gamble and the Beech-Nut Packing Company opened manufacturing plants in 1914 and 1922, respectively, their first outside the US.[19] Population and economic growth continued until the 1960s. In 1929 the city's first high-rise building, the Pigott Building, was constructed; in 1930 McMaster University moved from Toronto to Hamilton, in 1934 the second Canadian Tire store in Canada opened here; in 1940 the airport was completed; and in 1948, the Studebaker assembly line was constructed.[20] Infrastructure and retail development continued, with the Burlington Bay James N. Allan Skyway opening in 1958, and the first Tim Hortons store in 1964.

Since then, many of the large industries have moved or shut down operations in restructuring that also affected the United States.[19] The economy has shifted more toward the service sector, such as transportation, education, and health services.

On January 1, 2001, the new city of Hamilton was formed from the amalgamation of Hamilton and its five neighbouring municipalities: Ancaster, Dundas, Flamborough, Glanbrook, and Stoney Creek.[7] Before amalgamation, the "old" City of Hamilton had 331,121 residents and was divided into 100 neighbourhoods. The former region of Hamilton-Wentworth had a population of 490,268. The amalgamation created a single-tier municipal government ending subsidization of its suburbs. The new amalgamated city has 519,949 people in more than 100 neighbourhoods, and surrounding communities.[21]

In 1997 there was a devastating fire at the Plastimet plastics plant.[22] Approximately 300 firefighters battled the blaze, and many sustained severe chemical burns and inhaled volatile organic compounds when at least 400 tonnes of PVC plastic were consumed in the fire.[23]

Geography

Hamilton is in Southern Ontario on the western end of the Niagara Peninsula and wraps around the westernmost part of Lake Ontario; most of the city, including the downtown section, is on the south shore. Hamilton is in the geographic centre of the Golden Horseshoe. Its major physical features are Hamilton Harbour, marking the northern limit of the city, and the Niagara Escarpment running through the middle of the city across its entire breadth, bisecting the city into "upper" and "lower" parts. The maximum high point is 250m (820') above the level of Lake Ontario.[24]

According to all records from local historians, this district was called Attiwandaronia by the native Neutral people.[25] The first aboriginals to settle in the Hamilton area called the bay Macassa, meaning "beautiful waters".[21] Hamilton is one of 11 cities showcased in the book, Green City: People, Nature & Urban Places by Quebec author Mary Soderstrom, which examines the city as an example of an industrial powerhouse co-existing with nature.[26] Soderstrom credits Thomas McQuesten and family in the 1930s who "became champions of parks, greenspace and roads" in Hamilton.[27]

Hamilton Harbour is a natural harbour with a large sandbar called the Beachstrip. This sandbar was deposited during a period of higher lake levels during the last ice age, and extends southeast through the central lower city to the escarpment. Hamilton's deep sea port is accessed by ship canal through the beach strip into the harbour and is traversed by two bridges, the QEW's Burlington Bay James N. Allan Skyway and the lower Canal Lift Bridge.[28]

.jpg)

Between 1788 and 1793, the townships at the Head-of-the-Lake were surveyed and named. The area was first known as The Head-of-the-Lake for its location at the western end of Lake Ontario.[17] John Ryckman, born in Barton township (where present day downtown Hamilton is), described the area in 1803 as he remembered it: "The city in 1803 was all forest. The shores of the bay were difficult to reach or see because they were hidden by a thick, almost impenetrable mass of trees and undergrowth ... Bears ate pigs, so settlers warred on bears. Wolves gobbled sheep and geese, so they hunted and trapped wolves. They also held organized raids on rattlesnakes on the mountainside. There was plenty of game. Many a time have I seen a deer jump the fence into my back yard, and there were millions of pigeons which we clubbed as they flew low."[29]

George Hamilton, a settler and local politician, established a town site in the northern portion of Barton Township in 1815. He kept several east–west roads which were originally Indian trails, but the north–south streets were on a regular grid pattern. Streets were designated "East" or "West" if they crossed James Street or Highway 6. Streets were designated "North" or "South" if they crossed King Street or Highway 8.[30] The townsite's design, likely conceived in 1816, was commonplace. George Hamilton employed a grid street pattern used in most towns in Upper Canada and throughout the American frontier. The eighty original lots had frontages of fifty feet; each lot faced a broad street and backed onto a twelve-foot lane. It took at least a decade to sell all the original lots, but the construction of the Burlington Canal in 1823, and a new court-house in 1827 encouraged Hamilton to add more blocks around 1828–9. At this time he included a market square in an effort to draw commercial activity on to his lands, but the town's natural growth occurred to the north of Hamilton's plot.[31]

The Hamilton Conservation Authority owns, leases or manages about 4,500 hectares (11,100 acres) of land with the city operating 1,077 hectares (2,661 acres) of parkland at 310 locations.[32][33] Many of the parks are along the Niagara Escarpment, which runs from Tobermory at the tip of the Bruce Peninsula in the north, to Queenston at the Niagara River in the south, and provides views of the cities and towns at Lake Ontario's western end. The hiking path Bruce Trail runs the length of the escarpment.[34] Hamilton is home to more than 100 waterfalls and cascades, most of which are on or near the Bruce Trail as it winds through the Niagara Escarpment.[35] Visitors can often be seen swimming in the waterfalls during the summertime, although it is strongly recommended to stay away from the water: much of the watershed of the Chedoke and Red Hill creeks originates in storm sewers running beneath neighbourhoods atop the Niagara escarpment, and water quality in many of Hamilton's waterfalls is seriously degraded. High e. coli counts are regularly observed through testing by McMaster University near many of Hamilton's waterfalls, sometimes exceeding the provincial limits for recreational water use by as much as 400 times. The storm sewers in upstream neighbourhoods carry polluted runoff from streets and parking lots, as well as occasional raw sewage from sanitary lines that were improperly connected to the storm sewers instead of the separate sanitary sewer system. Notably, in March 2020 it was revealed that as much as 24 billion litres of untreated wastewater has been leaking into the Chedoke creek and Cootes' Paradise areas since at least 2014 due to insufficiencies in the city's sewerage and storm water management systems. [36]

Climate

Hamilton's climate is humid-continental, characterized by changeable weather patterns. In the Köppen classification, Hamilton it is on the Dfb/Dfa border found in southern Ontario because the average temperature in July is 22.0 °C (71.6 °F), although the east falls on the hot summer subtype towards Niagara Falls.[37] However, its climate is moderate compared with most of Canada. Hamilton's location on an embayment at the southwestern corner of Lake Ontario with an escarpment that divides the city's upper and lower parts results in noticeable disparities in weather over short distances. This is also the case with pollution levels, which depending on localized winds patterns or low clouds can be high in certain areas mostly originating from the city's steel industry mixed with regional vehicle pollution. With a July average of exactly 22.0 °C (71.6 °F),[38] the lower city is in a pocket of the Dfa climate zone found at the southwestern end of Lake Ontario (between Hamilton and Toronto and eastward into the Niagara Peninsula), while the upper reaches of the city fall into the Dfb climate zone.

The airport's open, rural location and higher altitude (240m vs. 85m ASL downtown) results in lower temperatures, generally windier conditions, and higher snowfall amounts than lower, built-up areas of the city. One exception is on early spring afternoons; when colder than air lake temperatures keep shoreline areas significantly cooler, under the presence of an east or north-east onshore flow.

The highest temperature ever recorded in Hamilton was 41.1 °C (106 °F) on 14 July 1868.[39] The coldest temperature ever recorded was -30.6 °C (-23 °F) on 25 January 1884.[40]

| Climate data for Hamilton, Ontario (Royal Botanical Gardens), 1981−2010 normals, extremes 1866−present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.3 (64.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

27.2 (81.0) |

31.1 (88.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

41.1 (106.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

41.1 (106.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.9 (30.4) |

0.1 (32.2) |

4.8 (40.6) |

11.7 (53.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

27.3 (81.1) |

25.9 (78.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

14.6 (58.3) |

7.7 (45.9) |

2.0 (35.6) |

13.1 (55.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.7 (23.5) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

0.5 (32.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

10.0 (50.0) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

8.6 (47.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −8.5 (16.7) |

−7.9 (17.8) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

2.4 (36.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

15.8 (60.4) |

11.4 (52.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

0.4 (32.7) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

4.0 (39.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30.6 (−23.1) |

−29.4 (−20.9) |

−28.3 (−18.9) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−22.8 (−9.0) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−30.6 (−23.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 56.8 (2.24) |

57.2 (2.25) |

63.7 (2.51) |

73.3 (2.89) |

85.5 (3.37) |

72.7 (2.86) |

82.7 (3.26) |

89.7 (3.53) |

80.9 (3.19) |

71.6 (2.82) |

91.3 (3.59) |

71.9 (2.83) |

897.1 (35.32) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 27.4 (1.08) |

26.4 (1.04) |

43.3 (1.70) |

70.1 (2.76) |

85.5 (3.37) |

72.7 (2.86) |

82.7 (3.26) |

89.7 (3.53) |

80.9 (3.19) |

71.6 (2.82) |

83.2 (3.28) |

46.8 (1.84) |

780.0 (30.71) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 32.4 (12.8) |

31.1 (12.2) |

18.3 (7.2) |

2.8 (1.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

7.5 (3.0) |

26.0 (10.2) |

118.1 (46.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 14.7 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 13.5 | 12.2 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 11.1 | 12.3 | 11.8 | 14.3 | 13.8 | 149.1 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 5.7 | 5.0 | 8.8 | 12.6 | 12.2 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 11.1 | 12.3 | 11.8 | 12.8 | 7.6 | 120.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 10.5 | 8.6 | 4.9 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 | 8.4 | 36.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 87.2 | 113.4 | 152.4 | 182.2 | 244.0 | 279.1 | 303.5 | 262.6 | 177.7 | 148.6 | 88.9 | 71.0 | 2,110.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 30.0 | 38.3 | 41.3 | 45.4 | 53.7 | 60.7 | 65.1 | 60.7 | 47.3 | 43.4 | 30.4 | 25.3 | 45.1 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source 1: Environment Canada[38][41][42][43] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas [44] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Hamilton | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average lake temperature °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

1.2 (34.1) |

1.3 (34.4) |

3.5 (38.4) |

7.7 (45.7) |

16.3 (61.3) |

22.8 (73.0) |

23.4 (74.1) |

21.1 (69.9) |

15.4 (59.6) |

9.4 (48.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

10.8 (51.3) |

| Source: Weather Atlas [44] | |||||||||||||

Culture

Hamilton's local attractions include the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum, the HMCS Haida National Historic Site,[45] Dundurn Castle (the residence of an Allan MacNab, the 8th Premier of Canada West),[46] the Royal Botanical Gardens, the Canadian Football Hall of Fame, the African Lion Safari Park, the Cathedral of Christ the King, the Workers' Arts and Heritage Centre, and the Hamilton Museum of Steam & Technology[47]

As of September 2018, there are 40 pieces in the city's Public Art Collection. The works are owned and maintained by the city.[48] Information and the locations of each piece in Public Art Collection can be viewed on this interactive map.

Founded in 1914, the Art Gallery of Hamilton is Ontario's third largest public art gallery. The gallery has over 9,000 works in its permanent collection that focus on three areas: 19th century European, Historical Canadian and Contemporary Canadian.[49]

The McMaster Museum of Art (MMA), founded at McMaster University in 1967, houses and exhibits the university's art collection of more than 7,000 objects,[50] including historical, modern and contemporary art, the Levy Collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, and a collection of over 300 German Expressionist prints. Hamilton has an active theatre scene, with the professional company Theatre Aquarius, plus long-time amateur companies, the Players' Guild of Hamilton and Hamilton Theatre Inc.. Many smaller theatre companies have also opened in the past decade, bringing a variety of theatre to the area.

Growth in the arts and culture sector has garnered media attention for Hamilton. A 2006 article in The Globe and Mail, entitled "Go West, Young Artist", focused on the Hamilton's growing art scene.[51] The Factory: Hamilton Media Arts Centre,[52] opened a new home on James Street North in 2006. Art galleries have sprung up on streets across the city: James Street, King William Street, Locke Street and King Street.The opening of the Downtown Arts Centre[53] on Rebecca Street has spurred creative activities in the core. The Community Centre for Media Arts[54] (CCMA) continues to operate in downtown Hamilton. The CCMA works with marginalized populations and combines new media services with arts education and skills development programming.[55]

Supercrawl is a large community arts and music festival that takes place in September in the James Street North area of the city.[56] In 2018, Supercrawl celebrated its 10th anniversary with over 220,000 visitors.[57]

In March 2015, Hamilton was host to the JUNO Awards,[58] which featured performances by Hedley, Alanis Morissette and Magic!. The award ceremony was held at the FirstOntario Centre in downtown Hamilton. During JUNOfest, hundreds of local acts performed across the city, bringing thousands of tourists.

Sports

Hamilton hosted Canada's first major international athletic event, the first Commonwealth Games (then called the British Empire Games) in 1930. Hamilton bid for the Commonwealth Games in 2010 but lost to New Delhi.[59] On November 7, 2009, in Guadalajara, Mexico, it was announced Toronto would host the 2015 Pan Am Games after beating out two rival South American cities, Lima, Peru and Bogotá, Colombia. The city of Hamilton co-hosted the Games with Toronto. Hamilton Mayor Fred Eisenberger said "the Pan Am Games will provide a 'unique opportunity for Hamilton to renew major sport facilities giving Hamiltonians a multi-purpose stadium, a 50-metre swimming pool, and an international-calibre velodrome to enjoy for generations to come'."[60] Hamilton's major sports complexes include Tim Hortons Field and FirstOntario Centre.

Hamilton is represented by the Tiger-Cats in the Canadian Football League. The team traces their origins to the 1869 "Hamilton Foot Ball Club". Hamilton is also home to the Canadian Football Hall of Fame museum.[61] The museum hosts an annual induction event in a week-long celebration that includes school visits, a golf tournament, a formal induction dinner and concludes with the Hall of Fame game involving the local CFL Hamilton Tiger-Cats at Tim Hortons Field.[62][63] The 109th championship game of the Canadian Football League, the Grey Cup, is scheduled to be played in Hamilton in 2021.[64]

In 2019, Forge FC debuted as Hamilton's soccer team in the Canadian Premier League. The team plays at Tim Hortons Field and share the venue with the Tiger-Cats. They finished their inaugural season as champions of the league.

In 2019, the Hamilton Honey Badgers will debut as Hamilton's basketball team in the Canadian Elite Basketball League. The team plays its home games at the FirstOntario Centre.

Hamilton hosted an NHL team in the 1920s called the Hamilton Tigers. The team folded after a players' strike in 1925.[65] Research in Motion CEO Jim Balsillie has shown interest in bringing another NHL team to southern Ontario. The NHL's Phoenix Coyotes filed for bankruptcy in 2009 and have included within their Chapter 11 reorganization a plan to sell the team to Balsillie and move the team and its operations to Hamilton, Ontario.[66] In late September, however, the bankruptcy judge did not rule in favour of Balsillie.

The Around the Bay Road Race circumnavigates Hamilton Harbour. Although it is not a marathon distance, it is the longest continuously held long distance foot race in North America.[67] The local newspaper also hosts the amateur Spectator Indoor Games.[67]

In addition to team sports, Hamilton is home to an auto race track, Flamboro Speedway and Canada's fastest half-mile harness horse racing track, Flamboro Downs.[68] Another auto race track, Cayuga International Speedway, is near Hamilton in the Haldimand County community of Nelles Corners, between Hagersville and Cayuga.[69]

| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forge FC | Canadian Premier League | Tim Hortons Field | 2017 | 1 |

| Hamilton Honey Badgers | Canadian Elite Basketball League | FirstOntario Centre | 2018 | 0 |

| Hamilton Tiger-Cats | Canadian Football League | Tim Hortons Field | 1950 | 8 |

| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dundas Blues | Provincial Junior Hockey League | J.L. Grightmire Arena | 1963 | |

| Dundas Real McCoys | Allan Cup Hockey | Dave Andreychuk Arena | 2000 | 1 |

| Hamilton Bengals | Ontario Junior B Lacrosse League | Dave Andreychuk Arena | 2015 | |

| Hamilton Bulldogs | Ontario Hockey League | FirstOntario Centre | 2015 | 1 |

| Hamilton Cardinals | Intercounty Baseball League | Bernie Arbour Memorial Stadium | 1957 | 1 |

| Hamilton City SC | Canadian Soccer League non-sanctioned | Heritage Field | 2016 | 0 |

| Hamilton Croatia | Hamilton & District Premier Soccer League's Elite Division | Croatian Sports and Community Centre of Hamilton | 1954 | 1 |

| Hamilton Hornets R.F.C. | Niagara Rugby Union | Mohawk Sports Park | 1954 | 0 |

| Hamilton Kilty B's | Greater Ontario Junior Hockey League | Dave Andreychuk Mountain Arena | 2018 | 0 |

| Hamilton Steelhawks | Allan Cup Hockey | Andreychuk Mountain Arena | 2015 | 0 |

| Hamilton Thunderbirds | Inter County Baseball League | Bernie Arbour Memorial Stadium | 2005 | 0 |

| Hamilton United | League1 Ontario | Ron Joyce Stadium | 2020 | 0 |

| Hamilton Wildcats | AFL Ontario | Mohawk Sports Park | 1997 | 0 |

| Stoney Creek Camels R.F.C. | Niagara Rugby Union | Saltfleet District High School | 1990 | 1 |

| Stoney Creek Generals | Allan Cup Hockey | Gateway Ice Centre | 2013 | 2 |

Attractions

Economy

The most important economic activity in Ontario is manufacturing, and the Toronto–Hamilton region is the country's most highly industrialized area. The area from Oshawa, Ontario around the west end of Lake Ontario to Niagara Falls, with Hamilton at its centre, is known as the Golden Horseshoe and had a population of approximately 8.1 million people in 2006.[70] The phrase was first used by Westinghouse President Herbert H. Rogge in a speech to the Hamilton Chamber of Commerce, on January 12, 1954. "Hamilton in 50 years will be the forward cleat in a golden horseshoe of industrial development from Oshawa to the Niagara River ... 150 miles long and 50 miles (80 km) wide...It will run from Niagara Falls on the south to about Oshawa on the north and take in numerous cities and towns already there, including Hamilton and Toronto."[71]

With sixty percent of Canada's steel produced in Hamilton by Stelco and Dofasco, the city has become known as the Steel Capital of Canada.[72] After nearly declaring bankruptcy, Stelco returned to profitability in 2004.[73] On August 26, 2007 United States Steel Corporation acquired Stelco for C$38.50 in cash per share, owning more than 76 percent of Stelco's outstanding shares.[74] On September 17, 2014, US Steel Canada announced it was applying for bankruptcy protection and it would close its Hamilton operations.[75]

A stand-alone subsidiary of Arcelor Mittal, the world's largest steel producer, Dofasco produces products for the automotive, construction, energy, manufacturing, pipe and tube, appliance, packaging, and steel distribution industries.[76] It has approximately 7,300 employees at its Hamilton plant, and the four million tons of steel it produces each year is about 30% of Canada's flat-rolled sheet steel shipments. Dofasco was North America's most profitable steel producer in 1999, the most profitable in Canada in 2000, and a long-time member of the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index. Ordered by the U.S. Department of Justice to divest itself of the Canadian company, Arcelor Mittal has been allowed to retain Dofasco provided it sells several of its American assets.[77]

Demographics

As per the 2016 Canadian census, 24.69% of the city's population was not born in Canada. Between 2001 and 2006, the foreign-born population increased by 7.7% while the total population of the Hamilton census metropolitan area (CMA) grew by 4.3%.

Hamilton is home to 26,330 immigrants who arrived in Canada between 2001 and 2010 and 13,150 immigrants who arrived between 2011 and 2016.[81]

Hamilton maintains significant Italian, English, Scottish, German and Irish ancestry. 130,705 Hamiltonians claim English heritage, while 98,765 indicate their ancestors arrived from Scotland, 87,825 from Ireland, 62,335 from Italy, 50,400 from Germany.[81]

In February 2014, the city's council voted to declare Hamilton a sanctuary city, offering municipal services to undocumented immigrants at risk of deportation.[82][83]

Hamilton also has a notable French community for which provincial services are offered in French. In Ontario, urban centres where there are at least 5000 Francophones, or where at least 10% of the population is francophone, are designated areas where bilingual provincial services have to be offered. As per the 2016 census, the Francophone community maintains a population of 6,760, while 30,530 residents, or 5.8% of the city's population, have knowledge of both official languages. The Franco-Ontarian community of Hamilton boasts two school boards, the public Conseil scolaire Viamonde and the Catholic Conseil scolaire catholique MonAvenir, which operate five schools (2 secondary and 3 elementary). Additionally, the city maintains a Francophone community health centre that is part of the LHIN (Centre de santé communautaire Hamilton/Niagara), a cultural centre (Centre français Hamilton), three daycare centres, a provincially funded employment centre (Options Emploi), a community college site (Collège Boréal) and a community organization that supports the development of the francophone community in Hamilton (ACFO Régionale Hamilton).

The top countries of birth for the newcomers living in Hamilton in the 1990s were: former Yugoslavia, Poland, India, China, the Philippines, and Iraq.[84]

Children aged 14 years and under accounted for 16.23% of the city's population, a decline of 1.57% from the 2011 census. Hamiltonians aged 65 years and older constituted 17.3% of the population, an increase of 2.4% since 2011.[81][85] The city's average age is 41.3 years.

54.9% of Hamiltonians are married or in a common-law relationship, while 6.4% of city residents are divorced.[81] Same-sex couples (married or in common-law relationships) constitute 0.08% (2,710 individuals) of the partnered population in Hamilton.[86]

The most described religion in Hamilton is Christianity although other religions brought by immigrants are also growing. The 2011 census indicates 67.6% of the population adheres to a Christian denomination, with Catholics being the largest at 34.3% of the city's population. The Christ the King Cathedral is the seat of the Diocese of Hamilton. Other denominations include the United Church (6.5%), Anglican (6.4%), Presbyterian (3.1%), Christian Orthodox (2.9%), and other denominations (9.8%). Other religions with significant populations include Islam (3.7%), Buddhist (0.9%), Sikh (0.8%), Hindu (0.8%), and Jewish (0.7%). Those with no religious affiliation accounted for 24.9% of the population.[87]

Environics Analytics, a geodemographic marketing firm that created 66 different "clusters" of people complete with profiles of how they live, what they think and what they consume, sees a future Hamilton with younger upscale Hamiltonians—who are tech savvy and university educated—choosing to live in the downtown and surrounding areas rather than just visiting intermittently. More two and three-storey townhouses and apartments will be built on downtown lots; small condos will be built on vacant spaces in areas such as Dundas, Ainslie Wood and Westdale to accommodate newly retired seniors; and more retail and commercial zones will be created.[88]

| Visible minority and Aboriginal population (Canada 2016 Census) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Population group | Population | % of total population | |

| Visible minority group Source:[89] |

South Asian | 22,105 | 4.2% |

| Chinese | 10,070 | 1.9% | |

| Black | 20,245 | 3.8% | |

| Filipino | 8,150 | 1.5% | |

| Latin American | 8,425 | 1.6% | |

| Arab | 10,330 | 2% | |

| Southeast Asian | 6,505 | 1.2% | |

| West Asian | 4,800 | 0.9% | |

| Other visible minority | 5,680 | 1.1% | |

| Multiple visible minority | 3,745 | 0.7% | |

| Total visible minority population | 100,060 | 19% | |

| Aboriginal group Source:[89] | First Nations | 8,445 | 1.6% |

| Métis | 3,085 | 0.6% | |

| Inuit | 125 | 0% | |

| Other Aboriginal | 290 | 0.1% | |

| Multiple Aboriginal identity | 185 | 0% | |

| Total Aboriginal population | 12,135 | 2.3% | |

| European Canadian | 415,735 | 78.7% | |

| Total population in private households | 527,930 | 100% | |

|

- Total number of respondents was 527,930.

Crime

The homicide rate in Hamilton in 2018 was 1.17 per 100,000 population.[90] Hamilton ranked first in Canada for police-reported hate crimes in 2016, with 12.5 hate crimes per 100,000 population.[91] Organized crime also has a notable presence in Hamilton with three centralized Mafia organizations in Hamilton, the Luppino crime family, the Papalia crime family, and the Musitano crime family.[92][93]

Government

Citizens of Hamilton are represented at all three levels of Canadian government - federal, provincial, and municipal. Following the 2015 Federal Election, representation in the Parliament of Canada will consist of five Members of Parliament representing the federal ridings of Hamilton West—Ancaster—Dundas, Hamilton Centre, Hamilton East—Stoney Creek, Hamilton Mountain, and Flamborough—Glanbrook. This election marked the first time Hamilton will have five Members of Parliament representing areas wholly within Hamilton's city boundaries, with previous boundaries situating rural ridings across municipal lines.[94]

Provincially, there are five elected Members of Provincial Parliament who serve in the Legislature of Ontario. Leader of the Ontario New Democratic Party and Leader of the Official Opposition, Andrea Horwath, represents Hamilton Centre, Paul Miller (NDP) represents Hamilton East-Stoney Creek, Monique Taylor (NDP) represents Hamilton Mountain, Sandy Shaw (NDP) represents Hamilton West—Ancaster—Dundas, and Progressive Conservative Donna Skelly represents Flamborough—Glanbrook.[95]

Hamilton's municipal government has a mayor, elected citywide, and 15 city councillors, elected individually by each of the city's wards, to serve on the Hamilton City Council. Presently, Hamilton's mayor is Fred Eisenberger, elected on October 22, 2018 to a third term.[96] Additionally, both Public and Catholic school board trustees are elected for defined areas ranging from two trustees for multiple wards to a single trustee for an individual ward.

The province grants the Hamilton City Council authority to govern through the Municipal Act of Ontario.[97] As with all municipalities, the Province of Ontario has supervisory privilege over the municipality and the power to redefine, restrict or expand the powers of all municipalities in Ontario.

The Criminal Code of Canada is the chief piece of legislation defining criminal conduct and penalty. The Hamilton Police Service is chiefly responsible for the enforcement of federal and provincial law. Although the Hamilton Police Service has authority to enforce, bylaws passed by the Hamilton City Council are mainly enforced by Provincial Offences Officers employed by the City of Hamilton.[98]

The Canadian Military maintains a presence in Hamilton, with the John Weir Foote Armoury in the downtown core on James Street North, housing the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry as well as the 11th Field Hamilton-Wentworth Battery and the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada. The Hamilton Reserve Barracks on Pier Nine houses the naval reserve division HMCS Star, 23 Service Battalion and the 23 Field Ambulance.

Education

Hamilton is home to several post-secondary institutions that have created many direct and indirect jobs in education and research. McMaster University moved to the city in 1930 and now has some 30,000 students, of which almost two-thirds come from outside the Hamilton region.[99][100] Brock University of St. Catharines, Ontario has a satellite campus used primarily for teacher education in Hamilton.[101] Colleges in Hamilton include:

- McMaster Divinity College, a Christian seminary affiliated with the Baptist Convention of Ontario and Quebec since 1957. McMaster Divinity College is on the McMaster University campus, and is affiliated with the university. The Divinity College was created as part of the process of passing governance of the university as a whole from the BCOQ to a privately chartered, publicly funded arrangement.

- Mohawk College, a college of applied arts and technology since 1967 with 10,000 full-time, 40,000 part-time, and 3,000 apprentice students.[102]

- Redeemer University College, a private Christian liberal arts and science university opened in 1982, with about a thousand students.[103]

From 1995 to 2001, the city was home to a satellite campus of the defunct francophone Collège des Grands-Lacs.[104]

Three school boards administer public education for students from kindergarten through high school. The Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board manages 114 public schools,[105] while the Hamilton-Wentworth Catholic District School Board operates 55 schools in the greater Hamilton area.[106] The Conseil scolaire Viamonde operates one elementary and one secondary school (École secondaire Georges-P.-Vanier), and the Conseil scolaire de district catholique Centre-Sud operates two elementary schools and one secondary school.

Calvin Christian School, Providence Christian School and Timothy Christian School are independent Christian elementary schools. Hamilton District Christian High School, Rehoboth Christian High School and Guido de Bres Christian High School are independent Christian high schools in the area. Both HDCH and Guido de Brès participate in the city's interscholastic athletics. Hillfield Strathallan College is on the West Hamilton mountain and is a CAIS member, non-profit school for children from early Montessori ages through grade twelve and has around 1,300 students. Columbia International College is Canada's largest private boarding high school, with 1,700 students from 73 countries.[107]

The Dundas Valley School of Art is an independent art school which has served the Hamilton region since 1964. Students range from 4 years old to senior citizens and enrollment as of February 2007 was close to 4,000. In 1998, a new full-time diploma programme was launched as a joint venture with McMaster University.[108]

The Hamilton Conservatory for the Arts is home to many of the area's talented young actors, dancers, musicians, singers and visual artists. The school has a keyboard studio, spacious dance studios, art and sculpting studios, gallery space and a 300-seat recital hall. HCA offers over 90 programs for ages 3–93, creating a "united nations" of arts under one roof.[109]

The Hamilton Literacy Council is a non-profit organization that provides basic (grades 1–5 equivalent) training in reading, writing, and math to English-speaking adults. The council's service is free, private, and one-to-one. It started to assist adults with their literacy skills in 1973.

Hamilton is home to two think tanks, the Centre for Cultural Renewal and Cardus, which deals with social architecture, culture, urbanology, economics and education and also publishes the LexView Policy Journal and Comment Magazine.[110]

Infrastructure

Transportation

The primary highways serving Hamilton are Highway 403 and the QEW. Other highways connecting Hamilton include Highway 5, Highway 6 and Highway 8. Public transportation is provided by the Hamilton Street Railway, which operates an extensive local bus system. Hamilton and Metrolinx will build a provincially-funded LRT line (Hamilton LRT) in the early 2020s.[111] Intercity public transportation, including frequent service to Toronto, is provided by GO Transit. The Hamilton GO Centre, formerly the Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo Railway station, is a commuter rail station on the Lakeshore West line of GO Transit. While Hamilton is not directly served by intercity rail, the Lakeshore West line does offer an off-peak bus connection and a peak-hours rail connection to Aldershot station in Burlington, which doubles as the VIA Rail station for both Burlington and Hamilton.

In the 1940s, the John C. Munro Hamilton International Airport was a wartime air force training station. Today, managed by TradePort International Corporation, passenger traffic at the Hamilton terminal has grown from 90,000 in 1996 to approximately 900,000 in 2002 with mostly domestic and vacation destinations in the United States, Mexico and Central America. The airport's mid-term growth target for its passenger service is five million air travelers annually. The airport's air cargo sector has 24–7 operational capability and strategic geographic location, allowing its capacity to increase by 50% since 1996; 91,000 metric tonnes (100,000 tons) of cargo passed through the airport in 2002. Courier companies with operations at the airport include United Parcel Service and Cargojet Canada.[112] In 2003, the city began developing a 30-year growth management strategy which called, in part, for a massive aerotropolis industrial park centred on Hamilton Airport. Advocates of the aerotropolis proposal, now known as the Airport Employment Growth District, tout it as a solution to the city's shortage of employment lands.[113] The closest other international airport to Hamilton is Toronto Pearson International Airport, located northeast of the city in Mississauga.

A report by Hemson Consulting identified an opportunity to develop 1,000 hectares (2,500 acres) of greenfields (the size of the Royal Botanical Gardens) that could create an estimated 90,000 jobs by 2031. A proposed aerotropolis industrial park at Highway 6 and 403, has been debated at City Hall for years. Opponents feel the city needs to do more investigation about the cost to taxpayers.[114]

Hamilton also plays a major role in Ontario's marine shipping industry as the Port of Hamilton is Ontario's busiest port handling between 9 to 12 million tonnes of cargo annually.

Health

The city is served by the Hamilton Health Sciences hospital network of five hospitals with more than 1,100 beds: Hamilton General Hospital, Juravinski Hospital, McMaster University Medical Centre (which includes McMaster Children's Hospital), St. Peter's Hospital and West Lincoln Memorial Hospital.[115] Other buildings under Hamilton Health Sciences include Juravinski Cancer Centre, Regional Rehabilitation Centre, Ron Joyce Children's Health Centre, and the West End Clinic and Urgent Care Centre. Hamilton Health Sciences is the largest employer in the Hamilton area and serves as academic teaching hospital affiliated with McMaster University and Mohawk College.[116] The only hospital in Hamilton not under Hamilton Health Sciences is St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton, which has 777 beds and three Campuses. This healthcare group provides inpatient and outpatient services, and mental illness or addiction help.[117][118]

Notable people

Sister cities

Hamilton is a sister city with Flint, Michigan, and its young amateur athletes compete in the CANUSA Games, held alternatively in the two cities since 1958.[59] Flint and Hamilton hold the distinction of having the oldest continuous sister-city relationship between a U.S. and Canadian city, since 1957.[119]

Other sister cities with Hamilton include:[120]

|

|

|

Other city relationships:[120]

See also

Notes

- Based on station coordinates provided by Environment Canada, climate data for was recorded near downtown Hamilton from January 1866 to August 1958, and April 1950 to present at the Royal Botanical Gardens.

References

- Bailey, Thomas Melville (1991). Dictionary of Hamilton Biography (Vol II, 1876–1924). W.L. Griffin Ltd.

- Daniel Nolan (December 22, 2011). "Bieber Fever hits the Hammer". The Hamilton Spectator. Metroland Media. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- Daniel Nolan (April 6, 2011). "Showdown in Steeltown". The Hamilton Spectator. Metroland Media. Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- Provincial Statutes of Canada, 1846, 9° vict. p. 981. Chapter LXXIII. An Act to amend the Act incorporating the Town of Hamilton, and to erect the same into a City.

- "(Code 3525005) Census Profile". 2016 census. Statistics Canada. 2017.

- "City of Hamilton Act, 1999". Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- Houghton, Margaret (2003). The Hamiltonians, 100 Fascinating Lives. James Lorimer & Company Ltd., Publishers Toronto. p. 6. ISBN 1-55028-804-0.

- "World University Rankings 2019". Times Higher Education. Times Higher Education. Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- Mackenzie, Ann. "A Short History of the United Empire Loyalists" (PDF). United Empire Loyalists' Association of Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 1, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- Weaver, John C. (1985). Hamilton: an illustrated history. James Lorimer & Company, Publishers. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-88862-593-6.

- The Origin and Development of the Road Network of the Niagara Peninsula, Ontario 1770-1851; Andrew F.Burghardt; McMaster University 1969

- Statutes of Upper Canada, 1833, 3° William IV, p. 58–68. Chapter XVII An act to define the Limits of the Town of Hamilton, in the District of Gore, and to establish a Police and Public Market therein.

- Smith, Wm. H. (1846). SMITH'S CANADIAN GAZETTEER - STATISTICAL AND GENERAL INFORMATION RESPECTING ALL PARTS OF THE UPPER PROVINCE, OR CANADA WEST:. Toronto: H. & W. ROWSELL. pp. 75–76. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- "A Brief History of Grand Lodge of Canada in the Province of Ontario:1855 ~ 2005 Then and Now". Grand Lodge of Canada in the Province of Ontario. Archived from the original on December 26, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.(Requires navigation to article).

- "Dufferin Masonic Lodge No. 291 A.F. & A.M." Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- "Chronology of the Regional Municipality of Hamilton-Wentworth". Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- Cataract Traction, by John M. Mills (Canadian Traction Series, Volume 2)(1971).

- "Industrial Hamilton – A Trail to the Future". Canada's Digital Collections. Archived from the original on May 28, 2009. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- "The Hamilton Memory Project; STUDEBAKER" (Press release). The Hamilton Spectator–Souvenir Edition. June 10, 2006. p. MP45.

- Manson, Bill (2003). Footsteps in Time: Exploring Hamilton's heritage neighbourhoods. North Shore Publishing Inc. ISBN 1-896899-22-6.

- Full text of "Plastimet Inc. fire Hamilton, Ontario: July 9-12, 1997 /" Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Archive.org. Retrieved on 2013-10-31.

- Deadly legacy: Is Plastimet killing firefighters? Archived October 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Thespec.com. Retrieved on 2013-10-31.

- Seward, Carrie. "About Hamilton; Physical features". Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- Watson, Milton (1938). Saga of a City. The Hamilton Spectator.

- Soderstrom, Mary (2006). Green City: People, Nature & Urban Places. Independent Pub Group. ISBN 1-55065-207-9.

- Lawson, B. (January 26, 2007). "Green City". The Hamilton Spectator. p. Go-7.

- "Burlington Bay/ Beach strip, Hamilton harbour, Skyway Bridge". Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008. (Requires navigation to relevant articles.)

- "A History of the city of Hamilton". Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- Bailey, Thomas Melville (1981). Dictionary of Hamilton Biography (Vol I, 1791–1875). W.L. Griffin Ltd.

- Weaver, John C. (1988). "Hamilton, George". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. VII (1836–1850) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Hamilton Conservation Authority. "HCH History: A Long History ..." Archived from the original on June 7, 2007. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

- City of Hamilton. "Hamilton Conservation Authority: City Parks". myhamilton.ca. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Bruce Trail Association". Archived from the original on July 11, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Waterfalls - Hamilton Conservation Authority". conservationhamilton.ca. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012.

- "Chedoke Creek's sad legacy of abuse: 10 things you didn't know". The Hamilton Spectator. March 9, 2020. ISSN 1189-9417. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- "Interactive Canada Koppen-Geiger Climate Classification Map". www.plantmaps.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- "Hamilton RBG, Ontario". Canadian Climate Normals 1981−2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- "Hamilton (July 1868)". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- "Hamilton (January 1884)". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- "Hamilton 1866-1958". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- "Hamilton RBG CS". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for February 2017". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- "Hamilton, Canada - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- "Parks Canada HMCS Haida website". Archived from the original on April 1, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Dundurn Castle". Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Workers Arts and Heritage Centre". Workers Arts and Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on April 9, 2011. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- "Public Art". City of Hamilton. October 1, 2018. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- "Art Gallery of Hamilton". Archived from the original on August 7, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- "McMaster University Fact Book 2009–2010" (PDF). International Research & Analysis, McMaster University. November 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 1, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- Mowat, Bruce (January 7, 2006). "Go west, young artist". Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on April 25, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- "The Factory: Hamilton Media Arts Centre". Archived from the original on December 22, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Downtown Arts Centre, Hamilton, Ontario". Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Community Centre for Media Arts". Archived from the original on December 12, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- Invest in Hamilton, Economic Development Review 2005, Wednesday, June 28, 2006, "City Remains Committed To Growing Arts & Culture" Page H20

- "Supercrawl - About". Supercrawl. 2018. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- Rockingham, Graham (September 17, 2018). "Happy 10th anniversary, Supercrawl ... and thanks for the party". The Hamilton Spectator. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- Kakoullis, Adrienne (January 9, 2014). "Hamilton to Host the 2015 JUNO Awards" (PDF). CTV. CARAS. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- "Tigertown Triumphs" (Press release). The Hamilton Spectator-Memory Project (Souvenir Edition). June 10, 2006. p. MP56.

- "Toronto, Hamilton win Pan Am Games bid". Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- "Canadian Football Hall of Fame & Museum". Archived from the original on March 30, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- "Five more walk into Canadian Football's hallowed shrine". Hamilton Scores!. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Ivor Wynne Stadium Information". Archived from the original on December 31, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Hamilton Tiger-Cats". Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- Wesley, Sam (2005). Hamilton's Hockey Tigers. James Lorimer & Company Ltd.

- "Report: Hamilton in Talks with Balsillie". ESPN. Archived from the original on May 13, 2009. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- "Tigertown Triumphs" (Press release). The Hamilton Spectator – Memory Project (Souvenir Edition) page MP56-MP68. June 10, 2006.

- "Flamboro Downs". Official web site. Archived from the original on December 31, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "New owners give Cayuga International Speedway its old name". Hamilton Scores!. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Portrait of the Canadian Population in 2006: Sub-provincial population dynamics, Greater Golden Horseshoe". Statistics Canada, 2006 Census of Population. March 13, 2007. Archived from the original on March 15, 2007. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- "Fast Facts from Hamilton's Past (www.myhamilton.ca)". Hamilton Public Library. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- Schneider, Joe (January 24, 2006). "Hamilton Steel capital of Canada". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- Wines, Leslie (December 24, 2004). "Stelco has returned to profitability". CBS Market Watch. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "U. S. Steel Agrees to Acquire Stelco". Stelco.com. Archived from the original on October 31, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "U.S. Steel Canada to sell Hamilton Works operations". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on September 25, 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- Forstner, Gordon (October 31, 2005). "Dofasco one of North America's most profitable steel companies". Dofasco. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- Hamilton Spectator News Wire (December 14, 2006). "Dofasco deadline looms". Hamilton Spectator. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 28, 2008.

- Bailey, Thomas Melville (1981). Dictionary of Hamilton Biography (Vol I, 1791–1875). W.L. Griffin Ltd. p. 143.

- "The Hamilton Memory Project" (Press release). The Hamilton Spectator- Souvenir Edition. June 10, 2006. p. MP38.

- Township of Barton. "Barton township population: 1816". Hamilton Public Library. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "Census Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on May 6, 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- Van Dongen, Matthew (February 12, 2014). "Hamilton to become 'sanctuary city' for newcomers who fear deportation". The Hamilton Spectator. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- Nursall, Kim (February 12, 2014). "Hamilton declares itself 'sanctuary city' for undocumented immigrants". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on February 14, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- "Hamilton: The top countries of birth for the newcomers arriving in Hamilton in the 1990s". 2001 Canadian Census. Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Community Profiles from the 2006 Census, Statistics Canada - Census Subdivision". statcan.ca. March 13, 2007. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "Families, Households and Marital Status Highlight Tables". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- "National Household Survey (NHS) Profile, 2011". statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- Choi, Paul (January 19, 2007). "How does your city grow?". The Hamilton Spectator. pp. Go-16.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "Census Profile, 2016 Census". 12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- "Homicide victims and rate per 100,000 population". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- Gaudet, Maxime (April 25, 2018). "Police-reported hate crime in Canada, 2016". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Unease as mobsters set free". National Post. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- "A short history of mob violence in Hamilton". thespec.com. May 3, 2017. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- "Part II – Amendments to the Initial Report (July 31, 2013) – Ontario – Objections - Redistribution Federal Electoral Districts". www.redecoupage-federal-redistribution.ca. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- "Current MPPs". Legislative Assembly of Ontario. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- Hamilton, City of (June 11, 2014). "Mayor's Office - Mayor Fred Eisenberger". www.hamilton.ca. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- "Municipal Act, 2001 (Requires navigation to article)". Ontario. Archived from the original on June 21, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Provincial Offences Act (Requires navigation to article)". Ontario. Archived from the original on July 4, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "McMaster's Economic Impact on the Hamilton Community". McMaster University. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "McMaster University Office of Public Relations". Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved September 9, 2008.

- "Brock University: Official web site". Archived from the original on March 26, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Mohawk College of Applied Arts & Technology". Archived from the original on May 16, 2006. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "About Redeemer". Archived from the original on November 11, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "New college goes hi-tech". Windsor Star, August 28, 1995.

- Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board » Maintenance Archived May 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine . Hwdsb.on.ca. Retrieved on 2013-07-26.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 8, 2011. Retrieved May 22, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Columbia International College: At a glance". Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- "Dundas Valley School of Art". Archived from the original on December 26, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Hamilton Conservatory for the Arts". Archived from the original on October 8, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Cardus". Cardus.ca. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- Craggs, Samantha (April 11, 2019). "Provincial budget confirms - again - that Hamilton will get LRT". CBC News. Archived from the original on June 25, 2019.

- "2009 Annual Report" (PDF). John C. Munro Hamilton International Airport. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved October 25, 2010.

- McNulty, Gord (December 18, 2007). "Energy City". The Hamilton Spectator.

- McacIntyre, Nicole (April 16, 2007). "Airport land 'key to future'". The Hamilton Spectator.

- "Our History". Hamilton Health Sciences. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- "Hamilton Health Sciences | Hamilton Chamber of Commerce". Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- "Melissa Farrell named new President of St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton". newswire.ca. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- "Our Vital Statistics". St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- "About Sister Cities of Flint Michigan". Archived from the original on October 19, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Hamilton Ontario Sister Cities". Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Hamilton Ontario Sister Cities". Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- "Maanshan, China". The Hamilton Mundialization Committee. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- "Mangalore, India". The Hamilton Mundialization Committee. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- "Monterrey, Mexico". The Hamilton Mundialization Committee. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- "Racalmuto, Sicily Italy". The Hamilton Mundialization Committee. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- "Sarasota Sister Cities". Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- "Shawinigan, Quebec Canada". The Hamilton Mundialization Committee. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- "Valle Peligna, Abruzzo Region Italy". The Hamilton Mundialization Committee. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hamilton, Ontario. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Hamilton, Ontario. |

- Official website

- Weaver, John C. (March 11, 2019). "Hamilton". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada.