Isan language

Isan or Northeastern Thai (Thai: ภาษาอีสาน, ภาษาไทยถิ่นตะวันออกเฉียงเหนือ, ภาษาไทยถิ่นอีสาน, ภาษาไทยอีสาน, ภาษาลาวอีสาน) is a group of Lao varieties spoken in the northern two-thirds of Isan in northeastern Thailand, as well as in adjacent portions of northern and eastern Thailand. It is the native language of the Isan people, spoken by 20 million or so people in Thailand,[4] a third of the population of Thailand and 80 percent of all Lao speakers, making it the second largest language in Thailand. The language remains the primary language in 88 percent of households in Isan.[4] It is commonly used as a second, third, or fourth language by the region's other linguistic minorities, such as Northern Khmer, Khorat Thai, Kuy, Nyah Kur, and other Tai or Austronesian-speaking peoples. The Isan language has unofficial status in Thailand and can be differentiated as a whole from the Lao language of Laos by the increasing use of Thai grammar, vocabulary, and neologisms.[5] Code-switching is common, depending on the context or situation. Adoption of Thai neologisms has also further differentiated Isan from standard Lao.[6]

| Isan | |

|---|---|

| Northeastern Thai, Thai Isan, Lao Isan, Lao (informally) | |

| |

| Native to | Thailand |

| Region | Isan and adjacent portions of northern and eastern Thailand. Also Bangkok. |

| Ethnicity | Isan, Northern Khmer and Thai Chinese |

Native speakers | (21 million cited 1995 census)[1] 2.3 million of these use both Isan and Thai at home[1] |

Kra–Dai

| |

| Thai Noi and Tai Tham alphabet (formerly)[2] Thai alphabet (de facto) | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | tts |

| Glottolog | nort2741[3] |

Classification

Isan, as a sub-set of the Lao language, falls within the Lao-Phuthai languages which link it with closely related languages such as Phuthai (BGN/PCGN Phouthai) and Tai Yo (BGN/PCGN Tai Gno). Thai falls within the related grouping of Chiang Saen languages which are spoken to the west and northwest of Isan. The Lao-Phuthai and Chiang Saen languages, together with the Northwestern Tai languages—comprising the languages of the Chinese Dai, Burmese Thai Shan and Assamese Ahom—and Southern Thai comprise the Southwestern branch of Tai languages. The Tai languages include the languages of the Zhuang, which are split into the Northern and Central branches of Tai languages. The Tai languages form a major division within the Kra-Dai language family, linking it with several other languages of southern China, such as the Hlai and Be languages of Hainan and the Kra and Kam-Sui languages on the Main and in neighbouring regions of northern Vietnam.[1]

Within Thailand, the speech of the Isan people is officially classified as a 'Northeastern' dialect of the Thai language and is referred to as such in most official and academic works concerning the language produced in Thailand. The use of 'Northeastern Thai' to refer to the language is re-enforced internationally with the descriptors in the ISO 639-3 and Glottolog language codes.[7] [8] Outside of official and academic Thai contexts, Isan is usually classified as a particular sub-grouping of the Lao language, such as by speakers themselves and most linguists, or as a separate language closely related to Lao in light of its different orthography and Thai influences that distinguish it overall, such as its classification in Glottolog and Ethnologue.[9][8][1]

Exonyms

In official Thai contexts, the language is classified as a dialect of the Thai language. It is academically and officially referred to by one of the following terms: Phasa Thai Tawan Ok Chiang Neua (Thai: ภาษาไทยตะวันออกเฉียงเหนือ /pʰaː săː tʰaj tàʔ wan ʔɔ`ːk tɕʰǐaŋ nɯːa/), 'Northeastern Thai language' or Phasa Thai Thin Isan (Thai: ภาษาไทยถิ่นอีสาน /pʰaː săː tʰaj tʰìn ʔiː săːn/), 'Thai language of Isan region' or 'Thai dialect of Isan'. In more casual contexts, the language is known in Thai as either Phasa Thai Isan (/pʰaː săː tʰaj ʔiː săːn/), 'Isan Thai language' or 'Isan language of Thailand' or the shorter form Phasa Isan (/pʰaː săː ʔiː săːn/), 'Isan language'.

The term 'Isan' was adopted in the late nineteenth century when the Khorat Plateau and the Lao peoples on the right bank were integrated into Siam (Thailand), and the local princes were replaced with regional governors that were grouped into new administrative regions called monthon, with the appearance of Monthon Isan in 1900. This was later applied to the entire region and later, to remove references to the Lao people and culture, to the region, its people and its language. The term was resurrected from Isanapura, an old Khmer city whose empire once extended into Isan, as well as a Sanskrit term for 'northeast', i.e., of Bangkok, and the aspect of Phra Isuan (BGN/PCGN Phra Isouane) or Shiva as guardian of the northeast direction.[9]

To Lao speakers in Laos and most of the linguistic minorities of Isan, the language is simply known as Phasa Lao (Lao: ພາສາລາວ /pʰáː săː láːw/, but is distinguished from the language of Laos by usages such as Phasa Lao Isane (Lao: ພາສາລາວອີສານ /pʰá ː săː láːw ʔiː săːn/), 'Isan Lao language' or 'Lao language of Isan' or Phasa Thai Lao (Lao: ພາສາໄທລາວ /pʰáː săː tʰáj láːw/, 'Lao Thai language' or 'Lao language of Thailand'. Phasa Thai Isane and Phasa Tai Isane, (both Lao: ພາສາໄທອີສານ /pʰáː săː tʰáj ʔiː săːn/), mean 'Isan Thai language' or 'Isan language of Thailand' and 'Isan people's language', respectively. In other languages of the world, the language is known as 'Isan' or translations of 'Northeastern Thai'.[7][8]

Endonyms

Native Isan speakers refer to their language simply as Phasa Lao (Northeastern Thai: ภาษาลาว /pʰáː săː láːw/), 'Lao language', or Phasa Tai Lao (Northeastern Thai: ภาษาไทลาว /pʰáː săː tʰáj láːw/), 'Lao people's language' or the homophonous Phasa Thai Lao (Northeastern Thai: ภาษาไทยลาว, 'Lao Thai language' or 'Lao language of Thailand'. References to the speech as the 'Lao language' is restricted to when in Isan or in private groups of native speakers, given the historical use of the word 'Lao' in Thai by peoples from other regions of Thailand but particularly Central Thailand and Bangkok as a prejudicial slur. In mixed settings, the terms Phasa Isan (Northeastern Thai: ภาษาไทอีสาน /pʰáː săː ʔiː săːn/, Phasa Tai Isan (Northeastern Thai: ภาษาไทอีสาน /pʰáː săː tʰáj ʔiː săːn/, 'Isan people's language' and Phasa Thai Isan (Northeastern Thai: ภาษาไทยอีสาน /pʰáː săː tʰáj ʔiː săːn/), 'Isan Thai language' or 'Isan language of Thailand' are also gaining in use, and the younger generation have begun to adopt the term 'Isan' over the 'Lao' used traditionally by the older generations.[9] The language is also affectionately or poetically known as Phasa Ban Hao (Northeastern Thai: ภาษาบ้านเฮา /pʰáː săː bȃːn háu/), 'Our home language' or 'our village language'.

Geographical distribution

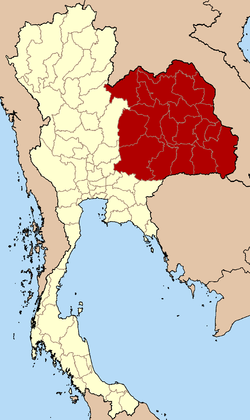

The Isan language is the primary language in the vast majority of households in the twenty province of Northeastern Thailand, also known as Phak Isan or the 'Isan region'. Most of the region falls within the Khorat Plateau, which is generally flat or slight undulating hills. The southern two-thirds of the region are drained by the important Mun (Northeastern Thai: มูล /múːn/) and, its major tributary, the Chi (Northeastern Thai: ซี /síː/) rivers. The northern third, separated by the Phu Phan Mountains (Northeastern Thai: ภูพาน pʰúː pʰáːn), is drained by the Loei (Northeastern Thai: เลย /lə́ːy/) and Songkhram (Northeastern Thai: สงคราม /sŏŋ kʰáːm/), rivers. The preservation of the Lao language in the region was in part due to its isolation. The Phetchabun and Dong Phaya Yen to the west, the Sankhamphaeng to the southwest and the Dongrak mountains along its southern edge separated Isan from direct Siamese control and influence of the Thai language until the early twentieth century. To the north and east, the Mekong River forms the 'boundary' between the Isan language and the Lao language of Laos. The riparian boundary was always porous, and three bridges as well as countless ferries transport thousands of people back and forth to conduct trade, shop, make pilgrimages to religious shrines, visit relatives and friends or travel every day. Outside the official region or Isan, large numbers of Isan speakers can be found in adjacent regions of Uttaradit and Phitsanulok in Northern Thailand and northern Sa Kaeo and Prachinburi provinces in Eastern Thailand. In addition, a large number of Isan people now reside across Thailand, particularly Bangkok.

In the southern third of Isan, the Isan speakers are still the majority, but sizeable linguistic minorities include the 1.4 million speakers of the archaic and conservative Khmer Surin dialect and 400 thousand speakers of Kuy. Speakers of Khmer Surin comprise almost half the population of Surin and a quarter of the populations of Buriram and Sisaket. In Nakhon Ratchasima, there are 600 thousand speakers of Thai Khorat or 'Khorat Thai' and are believed to be the descendants of Siamese soldiers and administrators and local Khmer and Lao women and unlike Isan, is a clear Central Thai dialect in pronunciation and lexis, with a handful of local influences from local languages and unique developments. Nakhon Ratchasima was the only part of the northeastern region to come under Siamese direct rule prior to the early twentieth century.

Tribal Tai languages include the closely related Phuan with 200 thousand speakers, Phu Thai with 156 thousand and Tai Yo with 50 thousand speakers and are spread out throughout the region. In addition, there are several Austroasiatic languages spoken by small groups in small, isolated clusters such as Bru, Thavung and Nyah Kur, a remnant population of Mon peoples. In urban districts, there are also substantial numbers of people who speak Central Thai as a first language as well as smaller numbers of Vietnamese and Chinese dialect speakers. The predominance of the Isan language in Northeastern Thailand is in stark contrast to the situation in Laos. Although the language enjoys official status and appears in writing, Lao speakers only make up half the population and is found in narrow bands hugging the Thai border, large cities and riparian areas with the language absent in the mountainous areas that make up most of the country where Austroasiatic, tribal Kra-Dai and Sino-Tibetan languages predominate. This also means that a considerable number of Lao speakers in Laos speak it as a second language.[10][11]

History

The Tai languages originated in what is currently known as central and southern China in an area stretching from Yunnan to Guangdong as well as Hainan and adjacent regions of northern Vietnam. Tai speakers arrived in Southeast Asia around 1000 CE, displacing or absorbing earlier peoples and setting up mueang (city-states) on the peripheries of the Indianised kingdoms of the Mon and Khmer peoples. The Tai kingdoms of the Mekong Valley became tributaries of the Lan Xang mandala (Isan: ล้านซ้าง, RSTG: lan chang, Lao: ລ້ານຊ້າງ, BGCN: lan xang, /lȃːn sȃːŋ/) from 1354–1707. Influences on the Isan language include Sanskrit and Pali terms for Indian cultural, religious, scientific, and literary terms as well as the adoption of the Pallava alphabet as well as Mon-Khmer influences to the vocabulary.

Lan Xang split into the Kingdom of Vientiane, the Kingdom of Luang Phrabang, and the Kingdom of Champasak, but these became vassals of the Thai state. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, several deportations of Lao peoples from the densely populated west bank of the Mekong to the hinterlands of Isan were undertaken by the Thai armies, especially after the revolt of Anouvong in 1828, when Vientiane was looted and depopulated. This weakened the Lao kingdoms as the population was shifted to the kingdoms in Isan and small pockets of western and north-central Thailand, under greater Thai control.[12][13]

Development of Isan

Isan speakers became politically separated from other Lao speakers after the Franco-Siamese War of 1893 would lead Siam to cede all of the territories east of the Mekong to France, which subsequently established the French Protectorate of Laos. In 1904, Sainyabuli and Champasak Provinces were ceded to France, leading to the current borders between Thailand and Laos. A 25 km demilitarised zone west of the river banks allowed for easy crossings, and Isan remained largely neglected for some time. Rebellions against Siamese and French incursions into the region included the Holy Man's Rebellion (1901-1904), led by self-proclaimed holy men. The Lao people also joined in the rebellion, but was crushed by Thai troops in Isan.[14] At first, Isan was administered by Lao local rulers subject to the Siamese Court under the monthon system of administration, but this was abolished in 1933, bringing Isan under the direct control of Bangkok.[15]

Thaification

Heavy-handed nationalist policies were adopted in 1933 with the end of the absolute monarchy in Thailand. Many were instituted during the premiership of Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram (1938-1944). Although Lao languages were banned from education in 1871, a new public education and new schools were built throughout Isan, and only Thai was to be used by government and media. References to Lao people were erased and propagation of Thai nationalism was instilled in the populace. The language was renamed "Northeastern Thai".

Discrimination against the Isan language and its speakers was commonplace, especially when large numbers of Isan people began arriving in Bangkok in the latter half of the 20th century, permanently or for seasonal work. Although this blatant discrimination is rarer these days, most of these nationalistic Thaification policies remain in effect.[16]

Post-war period to present

Resistance to Thai hegemony continued. During the course of World War II and afterwards, the Free Thai Movement bases in Isan made links with the Lao Issara movement. After the implementation of Thaification policies, many prominent Isan politicians were assassinated, and some Isan people moved to Laos. The Communist Party of Thailand led insurrections during the 1960s and 1980s, supported by the communist Pathet Lao and some factions of the Isan populace.[17] Integration continued, as highways and other infrastructure were built to link Isan with the rest of Thailand. Due to population pressures and unreliable monsoons of the region, Isan people began migrating to Bangkok for employment. Isan speakers began to shift to the Thai language, and the language itself is absorbing larger amounts of Thai vocabulary. Universities such as Mahasarakham and Khon Kaen are now offering classes on Isan language, culture, and literature. Attitudes towards regional cultures have relaxed and the language continues to be spoken, but Thai influences in grammar and vocabulary continue to increase.[18][19]

Legal status

Lao only enjoys official status in Laos. In Thailand, the local Lao dialects are officially classed as a dialect of the Thai language, and it is absent in most public and official domains. However, Thai has failed to supplant Lao as the mother tongue for the majority of Isan households. Lao features of the language have been stabilised by the shared history and mythology, mor lam folk music still sung in Lao, and a steady flow of Lao immigrants, day-labourers, traders, and growing cross-border trade.[20]

Language Status

The Lao (Isan) language in Thailand is classified by Ethnologue as a "de facto language of provincial identity" which is defined as a language that "is the language of identity for citizens of the province, but this is not mandated by law. Neither is it developed enough or known enough to function as the language of government business." It continues to be an important regional language for the ethnic Lao and other minorities that live beside them, but it does not have any official status in Thailand. Although the population of Lao speakers is much smaller in Laos, the language there enjoys official status, and it is the primary language of government, business, education, and inter-ethnic communication.[21] Even with close proximity to Laos, Isan speakers must master Thai and very few Isan people can read the Lao script due to lack of exposure.[18]

Written language usage and vitality

American linguist Joshua Fishman developed the Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (GIDS) to categorise the various stages of language death. The expanded GIDS (EGIDS) is still used to explain the status of a language on the continuum of language death.[22] The written language for Isan—both the secular Tai Noy script and the religious Tua Tham script—are currently at Stage IX which is described as a "language [that] serves as a reminder of heritage identity for an ethnic community, but no one has more than symbolic proficiency." Today, only a handful of monks in charge of the ancient temple libraries in Isan, some local professors, and a few experts are able to read and write the language.[18]:3–4[22]

Spoken language usage and vitality

The spoken language is currently at Stage VIA, or "vigorous", on the EGIDS scale, which is defined by Ethnologue as a language that is used for "face-to-face communication by all generations and the situation is sustainable". According to data from 1983, 88 percent of Isan households were predominantly Isan speaking, with 11 percent using both Thai and Isan at home, and only one percent using exclusively Thai.[18] Although this sounds promising for the continued future of the Isan language, there are many signs indicating that the language could reach Stage VIB, or "threatened", which is defined as a "language used for face-to-face communication within all generations, but it is losing users". As a strong command of Thai is necessary for advancement in most government, academic, and professional realms, and in order to work in areas like Bangkok where Isan is not the local language. The negative perception of the language, even among native speakers, often causes speakers to limit use of the language unless they are in the company of other Isan speakers. Parents may view the Isan language as a detriment to the betterment of their children, who must be able to speak central Thai proficiently to advance in academia or other career paths besides agriculture. Although there are large numbers of Isan speakers, the language is at risk from Thai relexification.[18] There is also a generational gap, with older speakers using more normative Lao features, whereas the youth are using a very "Thaified" version of Isan or switching to Thai generally. Many academics and Isan speakers are worried that the language may decline unless it can be promoted beyond its status as a de facto regional language and its written script rejuvenated. [23]

Thai-influenced language shift

The greatest influence on the Isan language comes from Thai. This is because Isan has been the target of official assimilation policies aimed to erase the culture and language and force nationalism based around the Thai monarchy and Central Thai culture. Thai spoken and written language is the only language of television, most radio stations, signage, government, courts, hospitals, literature, magazines, social media, movies, schools and mandatory for job placement and advancement, participating in wider society, education and social rise. Through Thai, Isan has also absorbed influences from Chinese, mainly the Teochew dialect, as well as English. Thai has also begun to displace the language of city life in the provincial capitals and major market towns in the region.

Language shift is definitely beginning to take hold. There does exist a considerable gap in language use between current university age students and their parents or grandparents, who continue to speak relatively traditional forms of the language. Many Isan people growing up in Bangkok often are unfamiliar with the language, and a larger number of children, especially in Isan's major cities, are growing up speaking only Thai, as parents in these areas often refuse to transmit the language. Those young people who do speak the language often heavily code-switch and rely on Thai vocabulary. It is uncertain if any of these students are able to revert to a 'proper' Isan, as the language still suffers the stigma of a rural, backward language of people who could serve as a fifth column of Lao efforts to dominate the region.[23]

Isan essentially exists in a diglossia, with the high language of Central Thai used in most higher spheres and the low language, Isan, used in the villages and with friends and relatives. Formal, academic and pop culture often demand knowledge of Thai as, as few Isan people can read old texts or modern Lao ones and Isan does not exist in these spheres. The language in its older form is best preserved in the poor, rural areas of Isan, many of which are far from market towns and barely accessible by roads despite improvements in integration. Many Isan academics that study the language lament the forced Thaification of their language. Wajuppa Tossa, a Thai professor who translated many of the traditional Isan stories directly from the palm-leaf manuscripts written in Tai Noy noted that she was unable to decipher the meaning of a handful of terms, some due to language change, but many due to the gradual replacement of Lao vocabulary and because, as she was educated in Thai, could not understand some of the formal and poetic belles-lettres, many of which are still current in Lao.[23]

Code-switching

Isan speakers have the choice of choosing a language that is either Thai or Lao or somewhere in between, with code-switching between languages a prominent feature of typical Isan speech. For example, if a man asks his younger brother, 'What is that man drinking?', he may receive one of several following responses that all mean, 'Older brother, the man over there drinks tea':, ranging from one diglossic extreme, i.e., using only Standard Thai to the other, using only Lao vocabulary which is often distinct from Thai.

- พี่ ผู้ชายนั่นดื่มน้ำชาครับ, phi phuchai nan deum namcha khrap /pʰîː pʰûː tɕʰaj nân dɯ`ːm nám tɕʰaː kʰráp/

Standard Thai - พี่ ผู้ชายนั่นดื่มน้ำชาเด้อครับ, *phi phuchai nan deum namcha doe khap /pʰīː pʰȕː tɕʰáj nȃn dɯ̄ːm nâm tɕʰáː dɯ̂ː kʰāp/.

Standard Thai, but switching over to Isan tones and use of the polite particle เด้อ, doe and a 'Lao-ised' pronunciation of the Thai male polite particle ครับ, khrap. - พี่ ผู้ชายนั่นกินน้ำซาเด้อครับ, *phi phuchai kin namsa doe khap /pʰīː pʰûː tɕʰaj nân kin nâm sáː dɯ̂ː kʰāp/

Mainly Isan vocabulary, but with Thai pronunciation and tones for ผู้ชาย, phuchai, and intrusion of the Thai male polite particle after the Isan one. - อ้าย ผู้บ่าวพู้นกินน้ำซาเด้อ, *ai phubao kin namsa doe /ȃːj pʰȕː bāːo pʰûːn kin nâm sáː dɯ̂ː/

Only using shared Lao vocabulary and pronunciation (devoid of Thai influence).

Cf. Lao ອ້າຍ ຜູ້ບ່າວພູ້ນກິນນ້ຳຊາແດ່/Archaic ອ້າຽຜູ້ບ່າວພູ້ນກິນນ້ຳຊາແດ່, ay phoubao kin namxa dé /ȃːj pʰȕː bāːo pʰûːn kin nâm sáː dɛ̄ː/)

Perceptions

Isan has always been Thailand's poorest, less educated and most rural region, with the vast majority of the local population engaged in traditional wet-rice cultivation and animal husbandry despite the region's infertile, salty soils and unpredictable rains making the area prone to either drought or severe floods. Agriculture employs over half the population, with another quarter of the population engaged in it part-time. Although it contains one-third of the total population of Thailand, the region only generates 10.9 per cent (2013) of the country's GDP. As a result, millions of Isan people leave during the dry season to find temporary work in menial jobs whilst others emigrate for longer terms but still maintain permanent residences in the region, and Isan people can typically found as taxi drivers, porters, factory workers, construction workers, restaurant workers, salon assistants, sex workers, janitors and other professions that require few skills or education[24]

When Thai people can understand words and phrases, the language sounds very polite, for Isan tends to use pronouns more frequently and uses vocabulary that often has cognates in Thai formal or literary language, especially frozen expressions, but otherwise, many words in spoken Lao and Isan are cognates of terms that are no longer very polite in spoken Thai. For example, Thai has two words for 'wife', mia (เมีย /mia/) and phanraya (ภรรยา /pʰan ráʔ jaː/). In Thai, mia is used by men but it is impolite in mixed company and Thai women generally object to the term being used (such as hearing a group of men refer to their own wives as 'broad' or 'woman'), as it is often used in many Thai expressions and insults that are negative towards women, and phanraya is the everyday, polite form used in general conversation. Lao mia (ເມັຽ) and Isan (เมีย), /mía/, unlike Thai, did not evolve to have a negative connotation and continues as the common word for 'wife' in vulgar, casual and formal circumstances whereas Lao phanragna (Archaic Laoພັນຣຍາ/modern Lao ພັນລະຍາ) and Isan (ภรรยา), /pʰán lāʔ ɲáː/ sounds as 'bookish' as referring to someone's wife as a 'consort'. As there is little advantage to speaking Isan and by virtue of its negative perception, even amongst speakers, the language shift goes unabated.[25]

Continued survival

The Lao folk music molam (หมอลำ, /mɔ̆ː lám/, cf. Lao: ໝໍລຳ/ຫມໍລຳ or lam lao (/lám láːo/, cf. Lao: ລຳລາວ) has gained in popularity in Thailand, with many Isan singing artists featured during off-peak hours on Thai national television. Crown Princess Sirindhorn was the patron of the 2003 "Thai Youth Mo Lam Competition" and Isan-language variants of the central Thai luk thung (ลูกทุ่ง, /lȗːk tʰúŋ/, cf. Lao: ລູກທົ່ງ, /lȗːk tʰoŋ/, louk thông) music are accepted in national youth competitions. Within Isan, many students participate in mo lam clubs where they learn the music.[18] Universities are also now offering classes about Isan language, culture, former alphabets, and literature. The Isan people are also exposed to a steady trickle of Laotian immigrants, seasonal immigrants, students as daily visitors, merchants, traders, and fishers.[20] Isan is also connected with Laos by three bridges, which link the cities of Nong Khai-Vientiane (also by rail), Mukdahan-Savannakhét, and Nakhon Phanom-Thakhek along the Thai-Lao border, respectively. The language will likely continue to have Thai relexification and gradual language shift as possible threats to its existence.[18]

Phonology

Consonants

Initials

Isan shares its original Lao consonant inventory, which compared to Thai, means it lacks /r/ and /tɕʰ/ and the common allophone of the latter, /ʃ/. However, it also includes the sounds /ɲ/ and /ʋ/, although /ʋ/ is sometimes /w/ depending on the speaker and region.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | /m/ | /n/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | ||

| ม | ณ1,น | ญ2,ย2 | ง | |||

| ມ, ໝ3 | ນ, ໜ3 | ຍ4, ຽ5 | ງ | |||

| Stop | Tenous | /p/ | /t/ | /tɕ/ | /k/ | /ʔ/ |

| ป | ฏ1,ต | จ | ก | อ | ||

| ປ | ຕ | ຈ | ກ | ອ | ||

| Aspirate | /pʰ/ | /tʰ/ | /tɕʰ/6 | /kʰ/ | ||

| ผ,พ,ภ | ฐ1,ฑ1,ฒ1,ถ,ท,ธ | ฉ,ช,ฌ1 | ข,ฃ7,ค,ฅ7,ฆ1 | |||

| ຜ, ພ | ຖ, ທ | ຊ | ຂ, ຄ | |||

| Voiced | /b/ | /d/ | ||||

| บ | ฎ1,ด | |||||

| ບ | ດ | |||||

| Fricative | /f/ | /s/ | /h/ | |||

| ฝ,ฟ | ซ,ศ1,ษ1,ส | ห,ฮ | ||||

| ຝ, ຟ | ສ, ຊ | ຫ, ຮ | ||||

| Approximate | /ʋ/8 | /l/ | /j/ | /w/9 | ||

| ว | ล,ฬ1 | ย | ว | |||

| ວ | ຣ, ລ, ຫຼ3 | ຢ, ຽ5 | ວ | |||

| Trill | /r/10 | |||||

| ร | ||||||

| ຣ | ||||||

- ^1 These letters are only used in loan words, generally from Indic languages such as Sanskrit and Pali.

- ^2 The sounds /j/ and /ɲ/ merged into /j/ in Thai, although Thai 'ญ' almost always corresponds to Lao and Isan /ɲ/. Thai 'ย' can be either /j/ and /ɲ/ and are distinguished from context in writing but it is phonemic in speech. As a vowel, it represents the /j/ element in diphthongs and triphthongs.

- ^3 The Lao ligatures 'ໝ' and 'ໜ' correspond and are sometimes written out 'ຫມ' and 'ຫນ', respectively, cf. Thai 'หน' and 'หม. The ligature 'ຫຼ' is used for both 'ຫລ' and 'ຫຣ', cf. Thai 'หล' and 'หร'. The silent /h/ is used to move the initial consonant to a high tone category for determining pronunciation.

- ^4 Lao 'ຍ' always represents /ɲ/ as a consonant but as a vowel, it represents the /j/ element in diphthongs and triphthongs.

- ^5 The Lao 'ຽ' was used until the mid-seventies as the form of 'ຍ' and 'ຢ' when it appeared as a secondary element or word finally. It is also used in these functions as a stylistic element and in writings of older people and the Lao diaspora. It also represents the /iːa/ element in the middle of words and formerly represented /ɔːy/ where it appeared as a final vowel.

- ^6 The sound /tɕʰ/ is not found in Isan, where it represents influence from Thai, but appears as /s/. The Lao letter 'ຊ' which is /s/ but often analogous to Thai /tɕʰ/ in cognates. Although /s/ is used in most Lao dialects, some areas of northern Laos, particularly some Phuan dialect speakers and speakers of other Tai languages speaking Lao as a second language have /tɕʰ/ or /tɕ/ in similar environments.

- ^7 Although still taught as part of the alphabet, 'ฃ' and 'ฅ' are obsolete and have been replaced by 'ข' and 'ค', respectively.

- ^8 In Isan and Lao, /ʋ/ is the general pronunciation of 'ว' and 'ວ', respectively, in variation with /w/.

- ^9 In Isan and Lao, /w/ is an alternate pronunciation of 'ว' and 'ວ', respectively. It is also the sound these letters make in both varieties when part of diphthongs or triphthongs. Use of /w/ in Isan is sometimes a Thai influence, as /ʋ/ dos not exist in Thai.

- ^10 The sound /r/ is not found in Isan or Standard Lao, where it is usually replaced by /l/. It is pronounced in some loan words from Sanskrit, Khmer, English or French by educated speakers in Laos and as a result of education in Thai and Thai influence in Isan. In contemporary Lao spelling, it is often removed and unwritten from consonant clusters and replaced by 'ລ' /l/ in writing elsewhere.

Clusters

There are two relatively common consonant clusters:

- /kw/ (กว)

- /kʰw/ (ขว,คว)

There are also several other, less frequent clusters recorded, though apparently in the process of being lost:

- /kr/ (กร), /kl/ (กล)

- /kʰr/ (ขร,คร), /kʰl/ (ขล,คล)

- /pr/ (ปร), /pl/ (ปล)

- /pʰr/ (พร), /pʰl/ (ผล,พล)

- /tr/ (ตร)

Finals

All plosive sounds are unreleased. Hence, final /p/, /t/, and /k/ sounds are pronounced as [p̚], [t̚], and [k̚] respectively.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | [m] ม |

[n] ญ,ณ,น,ร,ล,ฬ |

[ŋ] ง |

||

| Stop | [p] บ,ป,พ,ฟ,ภ |

[t] จ,ช,ซ,ฌ,ฎ,ฏ,ฐ,ฑ, ฒ,ด,ต,ถ,ท,ธ,ศ,ษ,ส |

[k] ก,ข,ค,ฆ |

[ʔ]* | |

| Approximant | [w] ว |

[j] ย |

- * The glottal stop appears at the end when no final follows a short vowel.

Vowels

The vowels of the Isan language are similar to those of Central Thai. They, from front to back and close to open, are given in the following table. The top entry in every cell is the symbol from the International Phonetic Alphabet, the second entry gives the spelling in the Thai alphabet, where a dash (–) indicates the position of the initial consonant after which the vowel is pronounced. A second dash indicates that a final consonant must follow.

| Front | Back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | |||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| High | /i/ -ิ |

/iː/ -ี |

/ɯ/ -ึ |

/ɯː/ -ื- |

/u/ -ุ |

/uː/ -ู |

| Mid | /e/ เ-ะ |

/eː/ เ- |

/ɤ/ เ-อะ |

/ɤː/ เ-อ |

/o/ โ-ะ |

/oː/ โ- |

| Low | /ɛ/ แ-ะ |

/ɛː/ แ- |

/a/ -ะ, -ั- |

/aː/ -า |

/ɔ/ เ-าะ |

/ɔː/ -อ |

The vowels each exist in long-short pairs: these are distinct phonemes forming unrelated words in Isan, but usually transliterated the same: เขา (khao) means "he/she", while ขาว (khao) means "white".

The long-short pairs are as follows:

| Long | Short | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Thai | IPA | Thai | IPA |

| –า | /aː/ | –ะ | /a/ |

| –ี | /iː/ | –ิ | /i/ |

| –ู | /uː/ | –ุ | /u/ |

| เ– | /eː/ | เ–ะ | /e/ |

| แ– | /ɛː/ | แ–ะ | /ɛ/ |

| –ื- | /ɯː/ | –ึ | /ɯ/ |

| เ–อ | /ɤː/ | เ–อะ | /ɤ/ |

| โ– | /oː/ | โ–ะ | /o/ |

| –อ | /ɔː/ | เ–าะ | /ɔ/ |

The basic vowels can be combined into diphthongs. For purposes of determining tone, those marked with an asterisk are sometimes classified as long:

| Long | Short | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Thai script | IPA | Thai script | IPA |

| –าย | /aːj/ | ไ–*, ใ–*, ไ–ย, -ัย | /aj/ |

| –าว | /aːw/ | เ–า* | /aw/ |

| เ–ีย | /iːə/ | เ–ียะ | /iə/ |

| – | – | –ิว | /iw/ |

| –ัว | /uːə/ | –ัวะ | /uə/ |

| –ูย | /uːj/ | –ุย | /uj/ |

| เ–ว | /eːw/ | เ–็ว | /ew/ |

| แ–ว | /ɛːw/ | – | – |

| เ–ือ | /ɯːə/ | เ–ือะ | /ɯə/ |

| เ–ย | /ɤːj/ | – | – |

| –อย | /ɔːj/ | – | – |

| โ–ย | /oːj/ | – | – |

Additionally, there are three triphthongs. For purposes of determining tone, those marked with an asterisk are sometimes classified as long:

| Thai script | IPA |

|---|---|

| เ–ียว* | /iəw/ |

| –วย* | /uəj/ |

| เ–ือย* | /ɯəj/ |

Dialects

Although as a whole, the Isan dialects are grouped separately from Lao dialects in Laos by influences from the Thai language, dialectal isoglosses mirror the population movements from Lao regions. These regional varieties vary in tone quality and distribution and a small number of lexical items, but all are mutually intelligible. Up to fourteen regional variations can be found within Isan, but they can be grouped into five principal dialect areas:[18][26][27]

| Dialect | Lao Provinces | Thai Provinces |

| Vientiane Lao (ภาษาลาวเวียงจันทน์) | Vientiane, Vientiane Prefecture, Bolikhamxai | Nong Bua Lamphu, Chaiyaphum, and parts of Nong Khai, Yasothon, Khon Kaen, and Udon Thani. |

| Northern Lao (ภาษาลาวเหนือ) | Louang Phrabang, Xaignabouli, Oudômxai, Phôngsaly, and Louang Namtha. | Loei and parts of Udon Thani, Khon Kaen, Phitsanulok, and Uttaradit. |

| Northeastern Lao/Tai Phuan (ภาษาลาวตะวันออกเฉียงเหนือ/ภาษาไทพวน) | Xiangkhouang and Houaphane. | Parts of Sakon Nakhon, Udon Thani.*2 |

| Central Lao (ภาษาลาวกลาง) | Savannakhét and Khammouane. | Nakhon Phanom, Mukdahan and parts of Sakon Nakhon, Nong Khai and Bueng Kan. |

| Southern Lao (ภาษาลาวใต้) | Champasak, Saravane, Xékong, and Attapeu. | Ubon Ratchathani, Amnat Charoen, and parts of Yasothorn, Buriram, Si Sa Ket, Surin, Nakhon Ratchasima and portions of Sa Kaew, Chanthaburi |

| Western Lao (ภาษาลาวตะวันตก) | Not spoken in Laos. | Kalasin, Maha Sarakham, Roi Et and portions of Phetchabun. |

Vientiane Lao dialect

The Vientiane dialect is spoken in northern Isan, in areas long-settled by Tai peoples from the early days of Lan Xang, such as Nong Bua Lamphu—once the seat of the ouparat (BGN/PCGN oupalat) of Lan Xang and later the Kingdom of Vientiane, Udon Thani, Chaiyaphum, Nong Khai and much of Loei provinces.[26] The Tai Wiang (Northeastern Thai: ไทเวียง /tʰáj wíaŋ/, Lao: ໄທວຽງ), or 'Vientiane people' of these areas were boosted by Siamese deportations of people from the left bank during the destruction of Vientiane in 1827 after the failed uprising of its last king, Chao Anouvong (RTGS Chao Anuwong). The Tai Wiang are also found in Khon Kaen and the Yasothon, where many districts traditionally speak Vientiane-like varieties. There are also a very small number of villages of Vientiane Lao speakers located in other regions of the Northeast.

Standard Lao is based on the speech of the old families of Vientiane as heard on television and broadcasts of government news media on radio. The dialect also extends over all Vientiane Province which surrounds the capital, as well as portions of Xaisômboun and Bolikhamxai provinces.[26] Many of the Lao-speaking regions of these areas were previously part of the Vientiane Province until administrative reforms led to their creation. As the city of Nong Khai, and much of the province, lies south on the opposite bank from Vientiane and is connected by bridge and several ferry services, the Isan speech of its inhabitants is almost indistinguishable from the speech of the Laotian capital.

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | ไม้เอก (อ่) | ไม้โท (อ้) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Rising | Middle | Low-Falling (Glottalised) | Low-Falling | Mid-Rising |

| Middle | Low-Rising | Middle | High-Falling (Glottalised) | High-Falling | Mid-Rising |

| Low | High-Rising | Middle | High-Falling | High-Falling | Middle (High Middle |

Northern Lao (Louang Phrabang) dialect

Northern Lao is not common is Isan, where it is found in western Loei and pockets of Udon Thani surrounded by Vientiane Lao speakers, but it is the predominate form of the Isan language spoken in the portions of Northern Thailand, such as the eastern portions of Uttaradit and Phitsanulok provinces that border Xaignabouli Province, Laos and Loei. In Laos, the dialect includes the traditional speech of the city of Louang Phrabang and the surrounding province and Xaignabouli, where Lao speakers predominate. In the other northern provinces of Oudômxai, Houaphan, Louang Namtha and Phôngsali, native Lao speakers are a small minority in the major market towns but Northern Lao, highly influenced by the local languages, is spoken as the lingua franca between ethnic groups.[26] The dialect was once an important prestige language of Laos, since the capital was the royal seat of Lan Xang for much of its history, and even under French rule and the capital long since moved to Vientiane, the Lao royal family continued to rule and deliver royal speeches in a refined form of the dialect until the brutal civil war that ousted it in 1975.

Northern Lao is quite distinct from the other Lao dialects, even though it is spoken just to the north of the Vientiane Lao dialect region. In vocabulary and intonation, it is quite similar to Tai Lanna language, due to geographic proximity, the brief dynastic union of Lanna and Lan Xang and the emigration of thousands of people from Lanna to Louang Phrabang after the former capitulated to Burmese invasions in 1551.[29] Because of this, Northern Lao is classified by Ethnologue as a Chiang Saen language like Tai Lanna.[1] The most striking difference between Northern Lao is the differentiation of two vowels 'ໄ◌' and 'ໃ◌', analogous to Thai 'ไ◌' and 'ใ◌' in cognates. In Standard Thai, Standard Lao and all other Lao dialects, these vowels are both /aj/, but Northern Lao distinguishes the latter, 'ໃ◌', as /aɯ/, although in Houaphan, the vowel is /əː/ as it is in Phuan. This distinction is preserved from Proto-Tai, where 'ໃ◌' and Thai 'ใ◌' correspond to Proto-Tai */aɰ/ and 'ໃ◌' and Thai 'ไ◌' correspond to Proto-Tai */aj/, respectively.[30]

| Source | Thai | Isan | Vientiane Lao | Northern Lao | Gloss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| */ʰmɤːl/ | ใหม่ mai |

/màj/ | ใหม่ mai |

/māj/ | ໃຫມ່ mai |

/māj/ | ໃຫມ່ *mau |

/māɯ/ | 'new' |

| */haɰ/ | ให้ hai |

hâj | ให้ hai |

hȁj | ໃຫ້ hai |

hȁj | ໃຫ້ hau |

/hȁɯ/ | 'to give' |

| */cɤɰ/ | ใจ chai |

/tɕaj/ | ใจ chai |

/tɕaj/ | ໃຈ chai |

tɕaj | ໃຈ *chau |

/tɕaɯ/ | 'heart' |

| */C̥.daɰ/ | ใน nai |

naj | ใน nai |

náj | ໃນ nai |

náj | ໃນ *nau |

/na᷇ɯ/ | 'inside' |

| */mwaj/ | ไม้ mai |

/máj/ | ไม้ mai |

/mâj/ | ໄມ້ mai |

/mâj/ | ໄມ້ mai |

/ma᷇j/ | 'wood'. 'tree' |

| */wɤj/ | ไฟ fai |

/faj/ | ไฟ fai |

/fáj/ | ໄຟ fai |

/fáj/ | ໄຟ fai |

/fa᷇j/ | 'fire' |

There are also a few minor differences in vocabulary that distinguish the speech of people of northern Laos, much of which is retained in the small areas of Isan where it is also spoken, such as western Loei.[30]

- ew, 'to play' (Northeastern Thai: เอว /ʔeːw/, Lao: ເອວ BGN/PCGN éo)

Vientiane Lao lin (Northeastern Thai: หลิ้น /lȉn/, Lao: ຫລິ້ນ, cf. Thai: เล่น /lên/ RTSG len) - ling, 'monkey' (Northeastern Thai: ลิง /lîŋ/, Lao: ລິງ)

Vientiane Lao ling (Northeastern Thai: ลีง /líːŋ/, Lao: ລີງ, cf. Thai: ลิง /liŋ/) - khanom pang, 'bread', (Northeastern Thai: ขนมปัง /kʰa᷇ʔ nǒm pâŋ/, Lao: ຂມົນປັງ BGN/PCGN khanôm pang

Vientiane Lao khao chi (Northeastern Thai: เข้าจี่ /kʰȁo cīː/, Lao: ເຂົ້າຈີ່, cf. Thai: ขนมปัง /kʰaʔ nǒm paŋ/) - khu, 'package' (Northeastern Thai: คู่ /kʰu᷇ː/, Lao: ຄູ່ BGN/PCGN khou)

Vientiane Lao ho (Northeastern Thai: ห่อ /hɔ̄ː/, Lao: ຫໍ່, cf. Thai: ห่อ /hɔ̀ː/)

The dialect is also unique for only having five tones, although some speakers in the mountainous areas may use more tones due to influences from their respective languages.[30] Due to the distinctive high pitch high-falling tone on words live syllables starting with low-class consonants is considered to sound 'softer' or 'lighter' to Lao speakers of other dialects.[31]

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | ไม้เอก (อ่) | ไม้โท (อ้) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Mid-Falling Rising | Middle | High-Falling (Glottalised) | High-Falling | Mid-Rising |

| Middle | Low-Rising | Middle | Mid-Rising (Glottalised) | High-Falling | Mid-Rising |

| Low | Low-Rising | Middle | Mid-Rising | Mid-Rising | Middle |

Northeastern Lao dialect (Tai Phouan)

Northeastern Lao or Phuan (BGN/PCGN Phouan) and is a associated with a distinct tribal Tai people. In Thailand, they are generally found in numerous villages of Sakon Nakhon and Udon Thani, and smaller concentrations in Bueng Kan, Nong Khai and Loei, but there are over two dozen Phuan villages scattered across northern and central Thailand where the Phuan were brought to develop the land, forced to dig canals and construct roads or defend the Siamese capital but were kept apart and forced to maintain their traditional black clothing and were thus able to preserve their language and identity. In Laos, the homeland of the Phuan people is the lowland areas of Xingkhouang and some districts of Houaphan.[26] As a northern-type language, the speech of Phuan communities is quite distinct from the neighbouring Isan villages where central and southern varieties predominate. Phuan preserves the distinction of 'ໃ◌' and Thai 'ใ◌', which correspond to Proto-Tai */aɰ/ and 'ໃ◌' and Thai 'ไ◌', which correspond to Proto-Tai */aj/, respectively. The former is realized as /əː/ and the latter as /aj/, similar to the Houaphan accent of the Northern Lao dialect.[30] Due to a tonal distribution more akin to Northern Lao and influences of Tai languages spoken in northern Laos, Phuan is classified as Chiang Saen language in Ethnologue.[1]

Due to the settlement of Phuan peoples outside of their original homeland of what is now Xiangkhouang Province of Laos, the tones of Phuan vary markedly between settlements due to drift because of isolation and influence of contact languages. However, there are a few traits that are shared between most Phuan varieties. Almost all Phuan speech have a distinct tone for words of low-class consonants marked with the mai ek (BGN/PCGN mai ék) that also appears in low-class consonant syllables with long vowels. Most Lao dialects pronounce all words with the same tone, regardless of consonant class, when marked with mai ek. Most Phuan dialects have six tones like most other Lao dialects, although some varieties spoken in Central Thailand and Northern Laos only have five.[30]

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | ไม้เอก (อ่) | ไม้โท (อ้) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low-Rising | Low | Middle (Glottalised) | Low | Mid-Rising |

| Middle | Mid-Rising | Low | High-Falling | Low | Mid-Rising |

| Low | Mid-Rising | Mid-Falling | High-Falling | Mid-Falling | Low |

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | ไม้เอก (อ่) | ไม้โท (อ้) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Rising | Low | Falling | Low | Middle |

| Middle | Rising | Low | Falling | Low | Middle |

| Low | Middle | Low-Falling Rising | High-Falling | Low-Falling Rising | Low |

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | ไม้เอก (อ่) | ไม้โท (อ้) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | High-Falling-Rising | High-Falling | High-Rising | High-Falling | High-Rising |

| Middle | Middle | High-Falling | High-Rising | High-Falling | High-Rising |

| Low | Middle | High-Rising | Low-Falling | High-Rising | High-Rising |

Central Lao

The central Lao dialect groupings predominate in the Lao provinces of Savannakhét and Khammouane, and the Thai province of Mukdahan and other regions settled by speakers from these regions.

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | ไม้เอก (อ่) | ไม้โท (อ้) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

| High | Rising | Middle | Low-Falling | Rising | Low-Falling |

| Middle | High-Falling | Middle | Rising-Falling | Rising | Low-Falling |

| Low | High-Falling | Middle | Rising-Falling | High-Falling | Middle |

Southern Lao

Southern Lao is the primary dialect of Champassak, most of the southern portions of Laos, portions of Thailand once under its control, such as Ubon Rachathani, and much of southern Isan, as well as small pockets in Steung Treng Province in Cambodia.

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | ไม้เอก (อ่) | ไม้โท (อ้) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

| High | High-Rising | Lower-Middle | Low (Glottalised) | Low | High-Rising |

| Middle | Middle | Lower-Middle | Low-Falling (Glottalised) | Low | High-Rising |

| Low | Mid-Falling | Lower-Middle | Low-Falling | Low-Falling | Lower-Middle (shortened) |

Western Lao

Western Lao does not occur in Laos, but can be found in Kalasin, Maha Sarakham, and Roi Et Provinces.

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | ไม้เอก (อ่) | ไม้โท (อ้) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

| High | Low-Rising | Middle | Low | Low | Low |

| Middle | Rising-Mid-Falling | Middle | Mid-Falling | Low | Low |

| Low | Rising-High-Falling | Low | High-Falling | Middle | Middle |

Related languages

- Central Thai (Thai Klang), is the sole official and national language of Thailand, spoken by about 20 million (2006).

- Northern Thai (Phasa Nuea, Lanna, Kam Mueang, or Thai Yuan), spoken by about 6 million (1983) in the formerly independent kingdom of Lanna (Chiang Mai). Shares strong similarities with Lao to the point that in the past the Siamese Thais referred to it as Lao.

- Southern Thai (Thai Tai, Pak Tai, or Dambro), spoken by about 4.5 million (2006)

- Phu Thai, spoken by about half a million around Nakhon Phanom Province, and 300,000 more in Laos and Vietnam (2006).

- Phuan, spoken by 200,000 in central Thailand and Isan, and 100,000 more in northern Laos (2006).

- Shan (Thai Luang, Tai Long, Thai Yai), spoken by about 100,000 in north-west Thailand along the border with the Shan States of Burma, and by 3.2 million in Burma (2006).

- Lü (Lue, Yong, Dai), spoken by about 1,000,000 in northern Thailand, and 600,000 more in Sipsong Panna of China, Burma, and Laos (1981–2000).

- Nyaw language, spoken by 50,000 in Nakhon Phanom Province, Sakhon Nakhon Province, Udon Thani Province of Northeast Thailand (1990).

- Song, spoken by about 30,000 in central and northern Thailand (2000).

Writing system

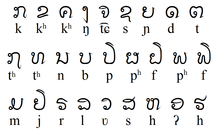

Tai Noi alphabet

The original writing system was the Akson Tai Noi (Northeastern Thai: อักษรไทน้อย /ák sɔ̆ːn tʰáj nɔ̑ːj/, cf. Lao: ອັກສອນໄທນ້ອຽ BGN/PCGN Akson Tai Noy), 'Little Tai alphabet' or To Lao (Northeastern Thai: โตลาว /to: láːo/, cf. Lao: ໂຕລາວ), which in contemporary Isan and Lao would be Tua Lao (Northeastern Thai: ตัวลาว /tuːa láːo/ and Lao: ຕົວລາວ, respectively, or 'Lao letters.' In Laos, the script is referred to in academic settings as the Akson Lao Deum (Lao: ອັກສອນລາວເດີມ /ák sɔ̆ːn láːo d̀ɤːm/, cf. Northeastern Thai: อักษรลาวเดิม RTGS Akson Lao Doem) or 'Original Lao script.' The contemporary Lao script is a direct descendant and has preserved the basic letter shapes. The similarity between the modern Thai alphabet and the old and new Lao alphabets is because both scripts derived from a common ancestral Tai script of what is now northern Thailand which was an adaptation of the Khmer script, rounded by the influence of the Mon script, all of which are descendants of the Pallava script of southern India.[29]

The Tai Noi script was the secular script used for personal letters, record keeping, signage, songs, poems, stories, recipes, medical texts and religious literature aimed at the laity. The earliest evidence of the script in what is now Thailand is an inscription at Prathat Si Bunrueang in Nong Bua Lamphu dated to 1510, and the last epigraphic evidence is dated to 1840 AD, although large numbers of texts were destroyed or did not survive the heat and humidity. The use of the script was banned in 1871 by royal decree, followed by reforms that imposed Thai as the administrative language of the region in 1898, but these edicts had little impact as education was done informally by village monks. The written language survived to some degree until the imposition of the radical Thaification policies of the 1930s, as the Central Thai culture was elevated as the national standard and all expressions of regional and minority culture were brutally suppressed.[37] Many documents were confiscated and burned, religious literature was replaced by royally sanctioned Thai versions and schools, where only the Thai spoken and written language was used, were built in the region. As a result, only a handful of people, such as academic experts, monks that maintain the temple libraries and some elderly people of advanced age are familiar with and can read material written in Tai Noi script. This has led to Isan being mainly a spoken language, and when it is written, if at all, it is written in the Thai script and spelling conventions that distance it from its Lao origins.[29]

Signage in Isan written in the Tai Noi script was installed throughout Khon Kaen University in 2013. Students were surveyed after the signs were put up, and most had a favorable reaction to the signage, as over 73 per cent had no knowledge of a previous writing system prior to the forced adoption of the Thai language and alphabet. Lack of a writing system has been cited as a reason for the lack of prestige speakers have for the language, disassociation from their history and culture and for the constant inroads and influence of the Thai language. Revival of the written language, however, is hampered by lack of support. Despite the easement of restrictions and prejudice against Isan people and their language, the Thaification policies that suppressed the written language remain the law of the land in Thailand today. Although contemporary Lao people from Laos can read Tai Noi material with only a little difficulty, Isan speakers are generally unfamiliar with the Lao script due to lack of exposure.[18][22]

'how are you?'

'where did it come from?'

'what did you eat with breakfast?'

'help me!'

'cavity of a rotten tooth'

'to return home'

'clean up after its finished'

'move in this direction'

Thai alphabet

The ban on all but the Thai language and alphabet in the classroom and official, public spheres rendered Isan speakers unable to read material written in the Lao language from Laos and forced them into a primarily oral culture, with all writing done in Thai with the Thai script. Eventually, Isan people developed an ad hoc system of transcribing their spoken language, using Thai spelling for cognate words, even those with consonant clusters that do not exist in Isan or Lao, but the core vocabulary of traditional Lao vocabulary is spelled analogously to what is used in Laos. To represent the different tones, as Lao dialects generally have six tones to the five of Thai, some writers use the rare tone marks written over 'ก'—'ก๋' and 'ก๊'—to better transcribe them. A more universal practice is the substitution of the letter 'ฮ' /h/ where the expected spelling would be 'ร' /r/ as many words in Isan have /h/ where the cognate term in Thai is /r/. This is similar to the Lao letter 'ຮ.' For example, the Proto-Tai word *rɤːn became the formal Thai: เรือน /rɯan/ but the commonplace word Northeastern Thai: เฮือน and Lao: ເຮືອນ, both pronounced /hɨ́ːan/. Similarly, traditionally Isan lacks the sound /tɕʰ/ and cognate words with Thai have /s/ instead, so writers often substitute 'ซ' for the Thai 'ช'. For example, Proto-Thai **ɟaːŋ became Thai: ช้าง /tɕʰáːŋ/ and Northeastern Thai: ซ้าง and Lao: ຊ້າງ, both pronounced /sȃːŋ/. The substitution of the other Thai letters that represent /tɕʰ/ is unknown with 'ส', although the Lao equivalent 'ສ' is used in Laos, such as Thai: ฉบับ /tɕʰaʔ bàp/ vs. Lao: ສະບັບ /sáʔ báp/. Isan speakers in this case use Thai spelling and Lao pronunciation.[38]

The use of the Thai alphabet and Thai spelling of cognate words provides a few challenges for accurately transcribing the Isan language. For instance, Isan and Lao have preserved a phonemic distinction between /j/ and /ɲ/, which in Lao is rendered separately with the letters 'ຢ' and 'ຍ', respectively. This differentiates Lao: ຢາ /jaː/, 'medicine,' and the similarly sounding Lao: ຍ່າ /ɲā/, 'paternal grandmother', whereas Isan speakers use 'ย' in both Northeastern Thai: ยา and Northeastern Thai: ย่า, respectively. The use of the Thai script and spelling rules, in terms of visual processing, contributes to the low prestige of the language. Since written in Thai script, the language looks fairly intelligible to Thai speakers even if the spoken language is different enough to cause misunderstandings. Because of these great phonological differences in tone, substitution of phonemes and simplification of consonant clusters, it further serves to make Isan to appear to be an inferior, substandard version of Thai and not its own unique variety. Nevertheless, this system is common in personal letters, social media and electronic communications between Isan speakers and is used to transcribe the lyrics of songs in the language, particularly the traditional Lao folk music molam'.[37]

| Comparison of Thai and Lao scripts | |

|---|---|

| Isan (written in Thai) |

|

| RTGS |

|

| Pronunciation (if read as Thai) |

|

| Lao |

|

| BGN/PCGN |

|

| Pronunciation (Lao and Isan) |

|

Tai Tham

The Tai Tham was historically known in the Lao-speaking world as tua tham (ตัวธรรม /tùa tʰám/, cf. Lao ຕົວທຳ/Archaic ຕົວທັມ, Toua Tham), 'dharma letters', due to their use primarily as the written language of Buddhist monks. The script was introduced into what is now Laos and Isan from Lan Na during the reign of King Setthathirath, who was crowned king of Lan Na and later became king of Lan Xang—although a prince of the latter—bringing both mandalas in personal union from 1546 until 1551. During this brief period, the large volumes of literature from the libraries in Chiengmai were either taken or copied and brought to the Lao people.[39]

Evidence of its use in what is now Isan include two stone inscriptions, such as the one housed at Wat Tham Suwannakuha in Nong Bua Lamphu, dated to 1564, and another from Wat Mahaphon in Maha Sarakham from the same period. The script was only used by the very religious or taught to the monks, as many sacred Pali sutras were preserved on palm-leaf manuscripts.[40] The script was generally not known to the laity, who would have instead used the Tai Noy script for most day-to-day things, although some, such as those who had joined the monastery for various lengths of time, as is the custom among males in various Therevada Buddhist Tai cultures. Despite its use as the religious language, often used to transcribe Pali texts, it was also used to write literature aimed at other monks and religious scholars, as well as notes and marginalia, in the Lao language.

Although Tua Tham is an abugida, spelling words according to the same general rules as Thai and Lao, the alphabet is unique in having a very different design, featuring round shapes, several ligatures, special vowels only used at the start of words, several consonants that have variant forms when at the end of a syllable and the habit of stacking letters, with the second letter in a sequence, where permissible, is written under the first. The Thai and Tai Noy/Lao scripts were derived from that of the Khmer, and are thus more sharply angled. Both the Mon and Khmer scripts share common descent from Brahmi via contacts with southern Indian traders, soldiers and religious leaders that used a Pallava script.[40]

As a result of its general suppression, Isan speakers use Thai-language and Thai-alphabet materials, although many monks in Isan offer advice or explanations in the Isan language, many of which are available for recordings, but transcriptions of these are now taken using the Thai alphabet and not Tai Noy or Tua Tham. Like Tai Noy, only a handful of experts and some older monks in charge of maintaining temple libraries are able to read the old texts. Although no longer in use in Isan, the alphabet is enjoying a resurgence in Northern Thailand, and is still used as the primary written script for the Tai Lü and Tai Khün languages spoken in the border areas where Thailand, Laos, Burma and southern China meet.[39]

Khom scripts

The Khom script (อักษรขอม /kʰɔ̆ːm/, cf. Lao ອັກສອນຂອມ, Aksone Khom) was not generally used to write the ancient Lao language of Isan, but was often used to write Pali texts, or Brahmanic rituals often introduced via the Khmer culture. Khom is the ancient Tai word for the Khmer people, who once populated and ruled much of the area before Tai migration and the assimilation of the local people to Tai languages. The modern Khmer alphabet is its descendant. It was generally not used to write the Lao language per se, but was often found in temple inscriptions, used in texts that preserve Brahmanic mantras and ceremonies, local mantras adopted for use in Tai animistic religion and other things usually concerned with Buddhism, Brahmanism or black magic, such as yantras and sakyan tattoos.

Also known by the same name is an obscure script that was invented for conveying secret messages that could not be deciphered by the French or Siamese forces that had divided Laos by Ong Kommandam, who had taken over as leader after the death of Ong Kèo during the Holy Man's Rebellion. As Ong Kommandam and many of his closest followers were speakers of Bahnaric languages spoken in southern Laos, most of the known texts in the language were written in Alak—Ong Kommandam's native language—and the Bahnaric Loven languages of Juk, Su' and Jru', and some in Lao.[41]

Although the shapes of the letters have a superficial resemblance to several writing systems in the area, it was not related to any of them. It enjoys some usage as a language of black magic and secrecy today, but only a handful of people are familiar with it. Although the word Khom originally referred to the Khmer, it was later applied to related Austroasiatic peoples such as the Lao Theung, many of which had supported Ong Kammandam.[41]

Overview of the relationship to Thai

Mutual intelligibility with Thai

Thai and Lao (including Isan varieties) are all mutually intelligible, neighboring, closely related Tai languages. They share the same grammar, similar phonological patterns and a large inventory of shared vocabulary. Thai and Lao share not only core Tai vocabulary but also a large inventory of Indic and Austroasiatic, mainly Khmer, loan words that are identical between them. Even though Thai and Lao have their own respective scripts, with Isan speakers using the Thai script, the two orthographies are related, with similar letter forms as spelling conventions. A Thai person would probably be able to understand most of written Isan (written in Thai with Thai etymologically Thai spelling), and may be able to understand the spoken language with a little exposure.

Although there are no barriers of mutual comprehension between a Lao speaker from Laos and an Isan speaker from Thailand, there are several linguistic and sociological factors that make the mutual intelligibility of Thai and Lao somewhat asymmetrical. First and foremost, most Lao speakers have knowledge of Thai. Most Lao speakers in Laos are able to receive Thai television and radio broadcasts and engage and participate in Thai websites and social media in Thai, but may not speak the language as well since Lao serves as the national and official state and public language of Laos. Isan speakers are almost universally bilingual, as Thai is the language of education, state, media and used in formal conversation. Isan speakers are able to read, write and understand spoken Thai, but their ability to speak Thai varies, with some from more remote regions unable to speak Thai very well, such as many children before schooling age and older speakers, but competence in Thai is based on factors such as age, distance from urban districts and education access.[42]

Thai speakers often have difficulty with some of the unique Lao features of Isan, such as very different tonal patterns, distinct vowel qualities and numerous common words with no Thai equivalent, as well as local names for many plants that are based on local coinages or older Mon-Khmer borrowings. A large number of Isan words and usages in Lao of Laos are cognates with old Thai usages no longer found in the modern language, or through drift, evolved to mean somewhat different things. Some Isan words are thus familiar to Thai students or enthusiasts of ancient literature or lakhon boran, soap opera-like serials that feature based on ancient Thai mythology or exploits of characters in previous periods, similar to the preservation of 'thou' and 'thee' in West Country English or modern students trying to parse the dialogue of Shakespeare's plays. The use of Thai etymological spelling of Isan words belies the phonological differences. Tones, which are phonemic in all Thai languages, are enough to make some words out of context to be perceived as something else. Same can be said for certain vowel transformations that took place in Lao after spelling came to be, that radically alter the pronunciation. Differences are enough that the film Yam Yasothon (แหยม ยโสธร Yaem Yasothon, Isan pronunciation /ɲɛ̑ːm ɲā sŏː tʰɔ́ːn/), 'Hello Yasothon'—better translated as 'Smile and Laugh Yasothon'—is shown in cinemas outside of Northeastern Thailand with Standard Thai subtitles. The movie, which features Isan actors and actresses, takes place in the Isan region, and surprisingly for a Thai movie with nationwide release, a predominately Isan dialogue.[43]

False cognates

Many Isan (and Lao) terms are very similar to words that are profane, vulgar or insulting in the Thai language, features which are much deprecated. Isan uses อี่ (/ʔīː/, cf. Lao: ອີ່) and อ้าย (/ʔâːj/, cf. Lao: ອ້າຍ/archaic ອ້າຽ), to refer to young girls and slightly older boys, respectively. In Thai, the similarly sounding อี, i (/ʔiː/) and ไอ้, ai (/ʔâj) are often prefixed before a woman's or man's name, respectively, or alone or in phrases which are considered extremely vulgar and insulting. This taboo expressions such as อีตัว "i tua", "whore" (/ʔiː nɔːŋ/) and ไอ้บ้า, "ai ba", "son of a bitch" (/ʔâj baː/).

In Isan and Lao, these prefixes are used in innocent ways as it does not carry the same connotation, even though they share these insults with Thai. In Isan, it is quite common to refer to a young girl named 'Nok' as I Nok (อี่นก, cf. Lao ອີ່ນົກ I Nôk or to address one's mother and father as i mae (อี่แม่, cf. Lao ອີ່ແມ່ I Mae, /ʔīː mɛ̄ː/) and I Pho (อี่พ่อ, cf. Lao ອີ່ພໍ່ i pho, /ʔīː pʰɔ̄ː/), respectively. Of course, as Thai only uses there cognate prefixes in fairly negative words and expressions, the sound of Isan i mae would cause some embarrassment in certain situations. The low status of the language is contributing to the language shift currently taking place among younger Isan people, and some Isan children are unable to speak the language fluently, but the need for Thai will not diminish as it is mandatory for education and career advancement.[23]

| Isan | Lao | IPA | Usage | Thai | IPA | Usage |

| บัก, bak | ບັກ, bak | /bák/ | Used alone or prefixed before a man's name, only used when addressing a man of equal or lower socio-economic status and/or age. | บัก, bak | /bàk/ | Alone, refers to a "penis" or in the expression บักโกรก, bak khrok, or an unflattering way to refer to someone as "skinny". |

| หำน้อย, ham noy | ຫຳນ້ອຍ/archaic ຫຳນ້ຽ, ham noy | /hăm nɔ̑ːj/ | Although ham has the meaning of "testicles", the phrase bak ham noy is used to refer to a small boy. Bak ham by itself is used to refer to a "young man". | หำน้อย, ham noy | /hăm nɔ´ːj/ | This would sound similar to saying "small testicles" in Thai, and would be a rather crude expression. Bak ham is instead ชายหนุ่ม, chai num (/tɕʰaːj nùm/) and bak ham noy is instead เด็กหนุ่ม, dek num (/dèk nùm/) when referring to "young man" and "young boy", respectively, in Thai. |

| หมู่, mu | ໝູ່, mou | /mūː/ | Mu is used to refer to a group of things or people, such as หมู่เฮา, mu hao (/mūː háo/, cf. Lao: ໝູ່ເຮົາ/ຫມູ່ເຮົາ), mou hao or "all of us" or "we all". Not to be confused for หมู, mu /mŭː/, 'pig', cf. Lao ໝູ/ຫມູ, mou or 'pig.' | พวก, phuak | /pʰǔak/ | The Isan word หมู่ sounds like the Thai word หมู (/mŭː/), 'pig', in most varieties of Isan. To refer to groups of people, the equivalent expression is พวก, phuak (/pʰǔak/), i.e., พวกเรา, phuak rao (/pʰǔak rào/ for "we all" or "all of us". Use of mu to indicate a group would make the phrase sound like "we pigs". |

| ควาย, khway | ຄວາຍ/archaic ຄວາຽ, khouay | /kʰúaːj/ | Isan vowel combinations with the semi-vowel "ວ" are shorted, so would sounds more like it were written as ควย. | ควาย, khway | /kʰwaːj/ | Khway as pronounced in Isan is similar to the Thai word ควย, khuay (/kʰúaj/), which is another vulgar, slang word for "penis". |

Phonological differences

Isan speakers share the phonology of the Lao language of Laos, so the differences between Thai and Isan are the same as the differences between Thai and Lao. Even in shared vocabulary, differences in vowel distributions, tone and consonant inventory can hinder comprehension even with cognate vocabulary. In typical words, Lao and Isan lack the /r/ and /tɕʰ/, instead substituting /l/ and /h/ for instances of Thai /r/ and /s/ for Thai /tɕʰ/. Lao and Isan, however, include the sounds /ʋ/ and /ɲ/ which are replaced with Thai /w/ and /j/, respectively, in cognate vocabulary.

Absence of consonant clusters

| Thai | Isan | Lao | Thai | Isan | Lao | Thai | Isan | Lao | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ก | /k/ | ก | /k/ | ກ | /k/ | ค | /kʰ/ | ค | /kʰ/ | ຄ | /kʰ/ | ผ | /pʰ/ | ผ | /pʰ/ | ຜ | /pʰ/ |

| กร | /kr/ | กร | คร | /kʰr/ | คร | ผล | /pʰl/ | ผล | |||||||||

| กล | /kl/ | กล | คล | /kʰl/ | คล | พ | /pʰ/ | พ | /pʰ/ | ພ | /pʰ/ | ||||||

| ข | /kʰ/ | ข | /kʰ/ | ຂ | /kʰ/ | ต | /t/ | ต | /t/ | ຕ | /t/ | พร | /pʰr/ | พร | |||

| ขร | /kʰr/ | ขร | ตร | /tr/ | ตร | พล | /pʰl/ | พล | |||||||||

| ขล | /kʰl/ | ขล | ป | /p/ | ป | /p/ | ປ | /p/ | |||||||||

| ปร | /pr/ | ปร | |||||||||||||||

| ปล | /pl/ | ปล | |||||||||||||||

In the development of the Lao language, the consonant clusters in the historical Tai languages were quickly lost. Although they sometimes appear in the oldest Lao texts, as they were not pronounced they quickly disappeared from writing. Clusters were re-introduced via loan words from Sanskrit, Khmer and other local Austroasiatic languages as well as in more recent times, via French and English. In these instances, the loan words are sometimes pronounced with clusters by very erudite speakers, but in general these are also simplified. For example, although Lao: ໂປຣກຣາມ /proːkraːm/, via French: programme /pʁɔgʁam/, and maitri (Lao: ໄມຕຣີ /máj triː/) from Sanskrit: मैत्री /maj triː/ are common, more often than not, they exist as ໂປກາມ /poːkaːm/ and ໄມຕີ /máj triː/, respectively.

The Thai language preserved the consonant clusters from older stages of the Tai languages and maintains them in writing and in careful pronunciation, although their pronunciation is relaxed in very informal speech. Due to the highly etymological spelling of Thai, consonant clusters from loan words such as Sanskrit and English are carefully preserved and pronounced. Isan, as a descendant of Lao, does not traditionally pronounce these clusters as they are absent from the spoken language, except in some high-brow words, but they are always written, as Isan uses the Thai alphabet and Thai spelling of cognate words. Although Isan speakers write maitri Thai: ไมตรี and prokraem Thai: โปรแกรม, via English 'programme' or 'program' (US), they use the pronunciations máj tiː/ and /poː kɛːm/.

| Thai | Isan | Lao | Gloss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| เพลง phleng |

/pʰleːŋ/ | เพลง phleng |

/pʰéːŋ/ | ເພງ phéng |

/pʰéːŋ/ | 'song' |

| ขลุ่ย khlui |

/kʰlùj/ | ขลุ่ย khlui |

/kʰūj/ | ຂຸ່ຍ khouay |

/kʰūj/ | 'flute' |

| กลาง klang |

/klaːŋ/ | กลาง klang |

/kàːŋ/ | ກາງ kang |

/kàːŋ/ | 'centre' 'middle' |

| ครอบครัว khropkhrua |

/kʰrɔ̑ːp kʰrua/ | ครอบครัว khropkhrua |

/kʰɔ̑ːp kʰúːa/ | ຄອບຄົວ khopkhoua |

/kʰɔ̑ːp kʰúːa/ | 'family' |

Merger of /r/ with /l/ or /h/

| Thai | Isan | Lao | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ร | /r/, /l/1 | ร | /r/, /l/ | /l/ | ຣ | /l/, /r/ |

| /l/ | ລ5 | /l/ | ||||

| ฮ3 | /h/ | ຮ4 | /h/ | |||

| ล6 | /l/ | ล | /l/ | ລ | /l/ | |

| ฬ6 | ฬ6 | |||||

| ห6 | /h/ | ห6 | /h/ | ຫ6 | /h/ | |

| ฮ6 | ฮ5 | ຮ5 | ||||

- ^1 Only in informal and relaxed environments.

- ^2 In technical and academic terms from Sanskrit, Khmer, French or English, Isan and Lao speakers may pronounce some words with /r/, this is common in erudite speakers, and is common amongst the older generation and Lao diaspora and in Isan, due to the use of Thai in formal contexts, code-switching and heavy Thai influence.

- ^3 Often used by Isan speakers writing Isan in Thai script to represent /h/.

- ^4 The letter 'ຮ'/h/ generally corresponds to words that featured /r/ in proto-Southwestern Tai as they are in Thai and was a modification of 'ຣ' /r/.

- ^5 Not all appearances of these letters correspond etymologically to /r/.

- ^6 The sounds of these letters are the result of different developments and do not descend from historical /r/.

In the modern Lao script, and the old Tai Noi script once used in what is now Isan, 'ຮ' /h/, itself a modification of the letter 'ຣ' /r/, was used to represent words that etymologically had /r/ but were now /h/. Native words that did not undergo transformation to /h/ instead became /l/ and were spelled with 'ລ'. However, /r/ was retained in some religious, technical and academic vocabulary, as well as loan words from Sanskrit, Khmer, French and English. In these instances, the pronunciation of 'ຣ' /r/ is /r/ amongst erudite speakers, particularly older people and those in the diaspora, and /l/ generally. Reforms after 1975 replaced most instances of 'ຣ' /r/ with 'ລ' /l/ in writing and speech. In Isan, the letter 'ฮ' /h/ is used analogously to Lao 'ຮ' /h/, although the Thai spelling of 'ร' is retained even when speakers pronounce it as /l/, possibly because even Central Thai speakers use /l/ in relaxed and informal environments. A notable exception is the word for 'to dance' or lam (Northeastern Thai: ลำ /lám/), which is cognate to Thai: รำ /ram/, but also appears with /l/ in Lao: ລຳ.

Although there are more words that are /l/ than /h/ that descend from Proto-Southwestern /r/, Lao speakers in Laos tend to use words with /h/ more frequently and consistently. In Isan, possibly due to the massive influence of Thai, /l/ is gaining usage at the expense of /h/. However, increased usage of /l/ or /h/ in speech is not a defining characteristic, with varieties on both sides of the Mekong having different distributions, although greater use of /h/ in Isan would definitely be a mark of a very conservative, rural dialect.

| Thai | Isan | Lao | Gloss | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| รถ rot |

/rót/ | รถ rot |

/lōt/ | ລົດ, ຣົຖ1 lôt, rôt'1 |

/lōt/, /rōt/2 | 'automobile', 'vehicle', 'car' |

| รัก rak |

/rák/ | ฮัก hak |

/hāk/ | ຮັກ hak |

/hāk/ | 'to love' |

| ร้อน ron |

/rɔ´ːn/ | ฮ้อน hon |

/hɔ̑ːn/ | ຮ້ອນ hon |

/hɔ̑ːn/ | 'centre' 'middle' |

| อรุณ arun |

/àʔ run/ | อรุณ arun |

/áʔ lún/, /àʔ run/2 | ອະລຸນ, ອະຣຸນ1 aloun, aroun* |

/áʔ lún/, /áʔ rún/2 | 'dawn' (poetic) |

| เรือ reua |

/rɯa/ | เรือ, เฮือ reua, heua^3 |

/lɨ́aː/, /hɨ́ːa/3 | ເຮືອ hua |

/hɨ́ːa/, /lɨ́aː/3 | 'boat' |

Merger of /tɕʰ/ with /s/

| Thai | Isan | Lao | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ฉ | /tɕʰ/, /ʃ/1 | ฉ | /tɕʰ/2, /ʃ/1 | /s/ | ສ | /s/ |

| ช | ช | ຊ7 | ||||

| ซ | /s/ | ซ3,7 | /s/ | |||

| ฌ5 | /tɕʰ/, /ʃ/1 | ฌ5 | /tɕʰ/2, /ʃ/1,2 | |||

| ศ6 | /s/ | ศ6 | /s/ | ສ7 | ||

| ษ6 | ษ6 | |||||

| ส | ส7 | |||||

- ^1 Allophonic variant common in Central Thai.

- ^2 These are the expected pronunciations according to Thai spelling and pronunciation; usage of these pronunciations are clear indicators of Thai intrusion or code-switching.

- ^3 This letter is often used by Isan speakers to represent /s/ in Thai cognates with 'ช' /tɕʰ/ in common vocabulary, but less so in formal terms.

- ^4 The Thai letter 'ฉ' corresponds to tone better with 'ส' although not written as such in Isan whereas Lao words have 'ສ' /s/ in analogous positions.

- ^5 This letter is only used in words of Sanskrit or Pali origin in Thai and has no correspondence in the Lao alphabet, but is replaced by 'ຊ' /s/

- ^6 These letters are only used for words of Sanskrit or Pali origin in Thai and have no correspondence in the Lao alphabet, but are replaced by 'ສ' /s/ in analogous positions. They are not related to the merger of /tɕʰ/ to /s/ in Isan and Lao.

- ^7 Not all instances of these letters are etymologically related to historical /tɕʰ/.

The Proto-Tai sounds */ɟ/ and */ʑ/ had likely merged in Southwestern Tai, and developed into /tɕʰ/ in Thai, but this was later merged into /s/ in Lao and traditional Isan pronunciation. As a result of this, Isan speakers writing the language in the Thai orthography will sometimes replace 'ช' /tɕʰ/ with 'ช' /s/ in cognate vocabulary, but unless they are code-switching into Thai or in very formal contexts that demand increased use of Thai-language phrases, Isan speakers traditionally replace all /tɕʰ/ with /s/ in speech. In Lao, the letter 'ຊ' /s/ is used in analogous positions where one would expect Thai 'ช' /tɕʰ/ or the rare letter 'ฌ' /tɕʰ/, the latter of which occurs only in rare loan words from Sanskrit and Pali. The Thai letter 'ฉ' /tɕʰ/ is also pronounced /s/ in Isan, but for sake of tone, corresponds better to 'ส' /s/ even though it is not written out this way. In Lao, the letter 'ສ' /s/ is used in analogous positions. The Thai letter 'ฉ' is generally only found in ancient words of Sanskrit or Khmer derivation and recent loan words from Teochew or Hokkien.

| Source | Thai | Isan | Lao | Gloss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| */ʑaɰ/1 | เช่า chao |

/tɕʰâw/ | เซ่า sao |

/sāu/ | ເຊົ່າ xao |

/sāu/ | 'to hire' | |

| */ʑaːj/1 | ชาย chai |

/tɕʰaːj/ | ซาย sai |

/sáːj/ | ຊາຍ xay |

/sáːj/ | 'male' | |

| */ɟaː/1 | ชา cha |

/tɕʰaː/ | ซา sa |

/sáː/ | ຊາ xa |

/sáː/ | 'tea' | |

| */ɟɤ/1 | ชื่อ chue |

/tɕʰɯ̂ː/ | ซื่อ sue |

/sɨ̄ː/ | ຊື່ xu |

/sɨ̄ː/ | 'name', 'to be called' | |

| Khmer: ឆ្លង chhlâng |

/cʰlɑːŋ/ | ฉลอง chalong |

/tɕʰaʔ lɔ̌ːŋ/ | ฉลอง chalong |

/sá lɔ̌ːŋ/ | ສະຫຼອງ salong |

/sá lɔ̌ːŋ/ | 'to celebrate' |

| Pali: झान jhāna |

/ɟʱaːna/ | ฌาน chan |

/tɕʰaːn/ | ฌาน chan |

/sáːn/ | ຊານ san |

/sáːn/ | 'meditation' |

| Sanskrit: छत्र chatra |

/cʰatra/ | ฉัตร chat |

/tɕʰàt/ | ฉัตร chat |

/sát/ | ສັດ sat |

/sát/ | 'royal parasol' |

| Min Nan Chinese: 雜菜 (Teochew) zap cai |

/tsap˨˩˧ tsʰaj˦̚ / | จับฉ่าย chapchai |

/tɕàp tɕʰàːj/ | จับฉ่าย chapchai |

/tɕáp sāːj/ | ຈັບສ່າຽ chapsay |

/tɕáp sāːj/ | 'Chinese vegetable soup' |

Resistance to the Thai /j/-/ŋ/ merger

| Proto-Tai | Thai | Isan | Lao |

|---|---|---|---|

| */ɲ/ | /j/ | /ɲ/ | |

| */j/ | /j/, /ɲ/ | ||

| */ʰɲ/ | /ɲ/ | ||

| */ˀj/ | /j/ | ||

Although Proto-Southwestern Tai maintained the distinctions of Proto-Tai */ɲ/, */j/, */ʰɲ/ and */ˀj/ into /j/, all of these merged into /j/ in Standard Thai. In the Lao-Phuthai languages and languages such as Phuan and Tai Lanna, /ɲ/ is the usual outcome although all these languages retain a small subset of words with /j/, with the distinction being phonemic. In the Lao alphabet, the two realisations are represented orthographically as 'ຍ' /ɲ/ and 'ຢ' /j/, although 'ຽ' traditionally replaced both letters at the end of syllables and in the combination now written 'ຫຍ', but this is still found in old writings and material produced by overseas Laotians of the older generations.

The loss of the distinction between /ɲ/ and /j/ in Thai occurred shortly after the adoption of writing, as there are some vestiges in the spelling. For instance, Proto-Tai */ˀj/, is suggested in the spelling of some Thai words with the sequence 'อย'. In Lao cognates, this developed into /j/ and not /ɲ/. Similarly, the Thai letter 'ญ' usually appears in loan words from Sanskrit, Pali, Khmer or Mon where /ɲ/ occurred in the source language, but is now /j/. In the handful of native Thai terms that have this spelling correspond to Lao /ɲ/.