Zhuang languages

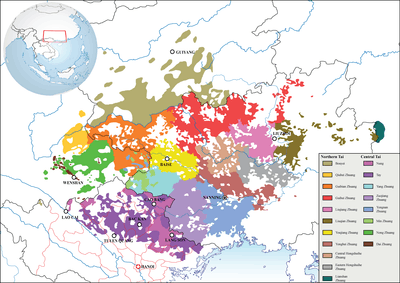

The Zhuang languages (autonym: Vahcuengh, pre-1982: Vaƅcueŋƅ, Sawndip: 話僮, from vah, 'language' and Cuengh, 'Zhuang'; simplified Chinese: 壮语; traditional Chinese: 壯語; pinyin: Zhuàngyǔ) are any of more than a dozen Tai languages spoken by the Zhuang people of Southern China in the province of Guangxi and adjacent parts of Yunnan and Guangdong. The Zhuang languages do not form a monophyletic linguistic unit, as northern and southern Zhuang languages are more closely related to other Tai languages than to each other. Northern Zhuang languages form a dialect continuum with Northern Tai varieties across the provincial border in Guizhou, which are designated as Bouyei, whereas Southern Zhuang languages form another dialect continuum with Central Tai varieties such as Nung, Tay and Caolan in Vietnam.[3] Standard Zhuang is based on the Northern Zhuang dialect of Wuming.

| Zhuang | |

|---|---|

| Vahcuengh (za), Hauqcuengh (zyb) Kauqnuangz, Kauqnoangz (zhn) Hoedyaej (zgn), Hauƽyəiч (zqe) Hauqraeuz, Gangjdoj (zyb, zhn, zqe) Kauqraeuz, Gangjtoj (zhn, zyg, zhd) | |

| Native to | China |

Native speakers | 16 million, all Northern Zhuang languages (2007)[1] |

Kra–Dai

| |

Standard forms | |

| Zhuang, Old Zhuang, Sawndip, Sawgoek | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | za |

| ISO 639-2 | zha |

| ISO 639-3 | zha – inclusive codeIndividual codes: zch – Central Hongshuihe Zhuangzhd – Dai Zhuang (Wenma)zeh – Eastern Hongshuihe Zhuangzgb – Guibei Zhuangzgn – Guibian Zhuangzln – Lianshan Zhuangzlj – Liujiang Zhuangzlq – Liuqian Zhuangzgm – Minz Zhuangzhn – Nong Zhuang (Yanguang)zqe – Qiubei Zhuangzyg – Yang Zhuang (Dejing)zyb – Yongbei Zhuangzyn – Yongnan Zhuangzyj – Youjiang Zhuangzzj – Zuojiang Zhuang |

| Glottolog | Nonedaic1237 = Daic; Zhuang is not a valid group[2] |

Geographic distribution of Zhuang dialects in Guangxi and related languages in Northern Vietnam and Guizhou | |

The Tai languages are believed to have been originally spoken in what is now southern China, with speakers of the Southwestern Tai languages (which include Thai, Lao and Shan) having emigrated in the face of Chinese expansion. Noting that both the Zhuang and Thai peoples have the same exonym for the Vietnamese, kɛɛuA1,[4] from the Chinese commandery of Jiaozhi in northern Vietnam, Jerold A. Edmondson posited that the split between Zhuang and the Southwestern Tai languages happened no earlier than the founding of Jiaozhi in 112 BC. He also argues that the departure of the Thai from southern China must predate the 5th century AD, when the Tai who remained in China began to take family names.[5]

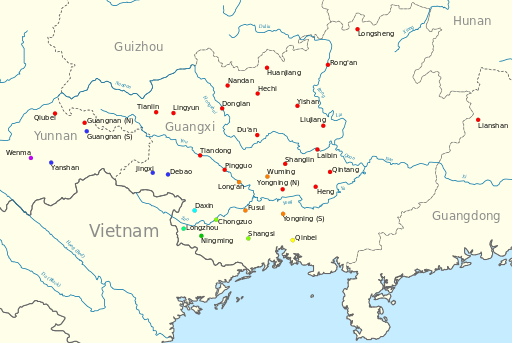

Surveys

Zhāng Jūnrú's (张均如) Zhuàngyǔ Fāngyán Yánjiù (壮语方言研究 [A Study of Zhuang dialects]) is the most detailed study of Zhuang dialectology published to date. It reports survey work carried out in the 1950s, and includes a 1465-word list covering 36 varieties of Zhuang. For the list of the 36 Zhuang variants below from Zhang (1999), the name of the region (usually county) is given first, followed by the specific village. The phylogenetic position of each variant follows that of Pittayaporn (2009)[6] (see Tai languages#Pittayaporn (2009)).

- Wuming – Shuāngqiáo 双桥 – Subgroup M

- Hengxian – Nàxù 那旭 – Subgroup N

- Yongning (North) – Wǔtáng 五塘 – Subgroup N

- Pingguo – Xīnxū 新圩 – Subgroup N

- Tiandong – Héhéng 合恒 – Subgroup N

- Tianlin – Lìzhōu 利周 – Subgroup N

- Lingyue – Sìchéng 泗城 – Subgroup N

- Guangnan (Shā people 沙族) – Zhěméng Township 者孟乡 – Subgroup N

- Qiubei – Gēhán Township 戈寒乡 – Subgroup N

- Liujiang – Bǎipéng 百朋 – Subgroup N

- Yishan – Luòdōng 洛东 – Subgroup N

- Huanjiang – Chéngguǎn 城管 – Subgroup N

- Rong'an – Ānzì 安治 – Subgroup N

- Longsheng – Rìxīn 日新 – Subgroup N

- Hechi – Sānqū 三区 – Subgroup N

- Nandan – Mémá 么麻 – Subgroup N

- Donglan – Chéngxiāng 城厢 – Subgroup N

- Du'an – Liùlǐ 六里 – Subgroup N

- Shanglin – Dàfēng 大丰 – Subgroup N

- Laibin – Sìjiǎo 寺脚 – Subgroup N

- Guigang – Shānběi 山北 – Subgroup N

- Lianshan – Xiǎosānjiāng 小三江 – Subgroup N

- Qinzhou – Nàhé Township 那河乡 – Subgroup I

- Yongning (South) – Xiàfāng Township 下枋乡 – Subgroup M

- Long'an – Xiǎolín Township 小林乡 – Subgroup M

- Fusui (Central) – Dàtáng Township 大塘乡 – Subgroup M

- Shangsi – Jiàodīng Township 叫丁乡 – Subgroup C

- Chongzuo – Fùlù Township 福鹿乡 – Subgroup C

- Ningming – Fēnghuáng Township 凤璜乡 – Subgroup B

- Longzhou – Bīnqiáo Township 彬桥乡 – Subgroup F

- Daxin – Hòuyì Township 后益乡 – Subgroup H

- Debao – Yuándì'èrqū 原第二区 – Subgroup L

- Jingxi – Xīnhé Township 新和乡 – Subgroup L

- Guangnan (Nóng people 侬族) – Xiǎoguǎngnán Township 小广南乡 – Subgroup L

- Yanshan (Nóng people 侬族) – Kuāxī Township 夸西乡 – Subgroup L

- Wenma (Tǔ people 土族) – Hēimò Township 黑末乡大寨, Dàzhài – Subgroup P

Varieties

The Zhuang language (or language group) has been divided by Chinese linguists into northern and southern "dialects" (fangyan 方言 in Chinese), each of which has been divided into a number of vernacular varieties (known as tǔyǔ 土语 in Chinese) by Chinese linguists (Zhang & Wei 1997; Zhang 1999:29-30).[7] The Wuming dialect of Yongbei Zhuang, classified within the "Northern Zhuang dialect," is considered to be the "standard" or prestige dialect of Zhuang, developed by the government for certain official usages. Although Southern Zhuang varieties have aspirated stops, Northern Zhuang varieties lack them.[8] There are over 60 distinct tonal systems with 5–11 tones depending on the variety.

Zhang (1999) identified 13 Zhuang varieties. Later research by the Summer Institute of Linguistics has indicated that some of these are themselves multiple languages that are not mutually intelligible without previous exposure on the part of speakers, resulting in 16 separate ISO 639-3 codes.[9][10]

Northern Zhuang

Northern Zhuang comprises dialects north of the Yong River, with 8,572,200 speakers[7][11] (ISO 639 ccx prior to 2007):

- Guibei 桂北 (1,290,000 speakers): Luocheng, Huanjiang, Rongshui, Rong'an, Sanjiang, Yongfu, Longsheng, Hechi, Nandan, Tian'e, Donglan (ISO 639 zgb)

- Liujiang 柳江 (1,297,000 speakers): Liujiang, Laibin North, Yishan, Liucheng, Xincheng (ISO 639 zlj)

- Hongshui He 红水河 (2,823,000 speakers): Laibin South, Du'an, Mashan, Shilong, Guixian, Luzhai, Lipu, Yangshuo. Castro and Hansen (2010) distinguished three mutually unintelligible varieties: Central Hongshuihe (ISO 639 zch), Eastern Hongshuihe (ISO 639 zeh) and Liuqian (ISO 639 zlq).[12]

- Yongbei 邕北 (1,448,000 speakers): Yongning North, Wuming (prestige dialect), Binyang, Hengxian, Pingguo (ISO 639 zyb)

- Youjiang 右江 (732,000 speakers): Tiandong, Tianyang, and parts of the Baise City area; all along the Youjiang River basin area (ISO 639 zyj)

- Guibian 桂边 (Yei; 827,000 speakers): Fengshan, Lingyun, Tianlin, Longlin, Yunnan Guangnan North (ISO 639 zgn)

- Qiubei 丘北 (Yei; 122,000 speakers): Yunnan Qiubei area (ISO 639 zqe)

- Lianshan 连山 (33,200 speakers): Guangdong Lianshan, Huaiji North (ISO 639 zln)

Southern Zhuang

Southern Zhuang dialects are spoken south of the Yong River, with 4,232,000 speakers[7][11] (ISO 639 ccy prior to 2007):

- Yongnan 邕南 (1,466,000 speakers): Yongning South, Fusui Central and North, Long'an, Jinzhou, Shangse, Chongzuo areas (ISO 639 zyn)

- Zuojiang 左江 (1,384,000 speakers): Longzhou (Longjin), Daxin, Tiandeng, Ningming; Zuojiang River basin area (ISO 639 zzj)

- Dejing 得靖 (979,000 speakers): Jingxi, Debao, Mubian, Napo. Jackson, Jackson and Lau (2012) distinguished two mutually unintelligible varieties: Yang (ISO 639 zyg) and Min (ISO 639 zgm)[13]

- Yanguang 砚广 (Nong; 308,000 speakers): Yunnan Guangnan South, Yanshan area (ISO 639 zhn)

- Wenma 文麻 (Dai; 95,000 speakers): Yunnan Wenshan, Malipo, Guibian (ISO 639 zhd)

Tày-Nùng language is also considered one of the varieties of Central Tai and shares a high mutual intelligibility with Wenshan Dai and other Southern Zhuang dialects in Guangxi.

Recently described varieties

Johnson (2011) distinguishes four distinct Zhuang languages in Wenshan Prefecture, Yunnan: Nong Zhuang, Yei Zhuang, Dai Zhuang, and Min Zhuang.[14] Min Zhuang is a recently discovered variety that has never been described previous to Johnson (2011). (See also Wenshan Zhuang and Miao Autonomous Prefecture#Ethnic groups)

Pyang Zhuang and Myang Zhuang are recently described Central Tai languages spoken in Debao County, Guangxi, China.[15][16]

Writing systems

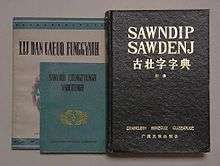

The Zhuang languages have been written in the ancient Zhuang script, Sawndip, for over a thousand years, and possibly Sawgoek previous to that. Sawndip is a Chinese character-based system of writing, similar to Vietnamese chữ nôm; some sawndip logograms were borrowed directly from Han characters, whereas others were original characters created from the components of Chinese characters. It is used for writing songs about every aspect of life, including in more recent times encouraging people to follow official family planning policy.

There has also been the occasional use of a number of other scripts including pictographics proto-writing, such as in the example at right.

In 1957 Standard Zhuang using a mixed Latin-Cyrillic script was introduced, and in 1982 this was changed to Latin script; these are referred to as the old Zhuang and new Zhuang, respectively. Bouyei is written in Latin script.

See also

References

- Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Daic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Bradley, David (2007). "East and Southeast Asia". In Moseley, Christopher (ed.). Encyclopedia of the World's Engangered Languages. Routledge. pp. 349–422. ISBN 978-1-135-79640-2. p. 370.

- A1 designates a tone.

- Edmondson, Jerold A. (2007). "The power of language over the past: Tai settlement and Tai linguistics in southern China and northern Vietnam" (PDF). In Jimmy G. Harris; Somsonge Burusphat; James E. Harris (eds.). Studies in Southeast Asian languages and linguistics. Bangkok, Thailand: Ek Phim Thai Co. pp. 39–63. (see p. 15 of preprint)

- Pittayaporn, Pittayawat (2009). The Phonology of Proto-Tai (Ph.D. thesis). Department of Linguistics, Cornell University. hdl:1813/13855.

- Zhang Yuansheng and Wei Xingyun. 1997. "Regional variants and vernaculars in Zhuang." In Jerold A. Edmondson and David B. Solnit (eds.), Comparative Kadai: The Tai branch, 77–96. Publications in Linguistics, 124. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington. ISBN 978-1-55671-005-6.

- Luo Yongxian. 2008. "Zhuang". In Diller, Anthony, Jerold A. Edmondson, and Yongxian Luo eds. 2008. The Tai–Kadai Languages. Routledge Language Family Series. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1457-5.

- Johnson, Eric C. (2007). "ISO 639-3 Registration Authority, Change Request Number 2006-128" (PDF).

- Tan, Sharon (2007). "ISO 639-3 Registration Authority, Change Request Number 2007-027" (PDF).

- 张均如 / Zhang Junru, et al. 壮语方言研究 / Zhuang yu fang yan yan jiu [A Study of Zhuang dialects]. Chengdu: 四川民族出版社 / Sichuan min zu chu ban she, 1999.

- Hansen, Bruce; Castro, Andy (2010). "Hongshui He Zhuang dialect intelligibility survey". SIL Electronic Survey Reports 2010-025.

- Jackson, Bruce; Jackson, Andy; Lau, Shuh Huey (2012). "A Sociolinguistic Survey of the Dejing Zhuang Dialect Area". SIL Electronic Survey Reports 2012-036..

- "SIL Electronic Survey Reports: A sociolinguistic introduction to the Central Taic languages of Wenshan Prefecture, China". SIL International. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- http://lingweb.eva.mpg.de/numeral/Zhuang-Fuping.htm

- Liao Hanbo. 2016. Tonal development of Tai languages. M.A. dissertation. Chiang Mai: Payap University.

Bibliography

- Zhuàng-Hàn cíhuì 壮汉词汇 (Nanning, Guǎngxī mínzú chūbǎnshè 广西民族出版社 1984).

- Edmondson, Jerold A. and David B. Solnit, ed. Comparative Kadai: The Tai Branch. Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics; [Arlington]: University of Texas at Arlington, 1997.

- Johnson, Eric C. 2010. "A sociolinguistic introduction to the Central Taic languages of Wenshan Prefecture, China." SIL Electronic Survey Reports 2010-027: 114 p. http://www.sil.org/silesr/abstract.asp?ref=2010-027.

- Luo Liming, Qin Yaowu, Lu Zhenyu, Chen Fulong (editors) (2004). Zhuang–Chinese–English Dictionary / Cuengh Gun Yingh Swzdenj. Nationality Press, 1882 pp. ISBN 7-105-07001-3.

- Tán Xiǎoháng 覃晓航: Xiàndài Zhuàngyǔ 现代壮语 (Beijing, Mínzú chūbǎnshè 民族出版社 1995).

- Tán Guóshēng 覃国生: Zhuàngyǔ fāngyán gàilùn 壮语方言概论 (Nanning, Guǎngxī mínzú chūbǎnshè 广西民族出版社 1996).

- Wang Mingfu, Eric Johnson (2008). Zhuang Cultural and Linguistic Heritage. The Nationalities Publishing House of Yunnan. ISBN 7-5367-4255-X.

- Wéi Qìngwěn 韦庆稳, Tán Guóshēng 覃国生: Zhuàngyǔ jiǎnzhì 壮语简志 (Beijing, Mínzú chūbǎnshè 民族出版社 1980).

- Zhang Junru 张均如, et al. 壮语方言研究 / Zhuang yu fang yan yan jiu [A Study of Zhuang dialects]. Chengdu: 四川民族出版社 / Sichuan min zu chu ban she, 1999.

- Zhou, Minglang: Multilingualism in China: The Politics of Writing Reforms for Minority Languages, 1949–2002 (Walter de Gruyter 2003); ISBN 3-11-017896-6; pp. 251–258.

External links

| Look up Category:Zhuang language in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Zhuang edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zhuang writing. |

- Swadesh vocabulary list of basic words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Zhuang language & alphabet, Omniglot

- The prospects for the long-term survival of Non-Han minority languages in the south of China

- Field Notes on the Pronominal System of Zhuang "A major case of language shift is occurring in which the use of Zhuang and other minority languages is restricted mainly to rural areas because Zhuang-speaking villages, like Jingxi, which develop into towns become more and more of Mandarin-speaking towns. Zhuang-speaking villages become non-Zhuang-speaking towns! And children of Zhuang-speaking parents in cities are likely not to speak Zhuang as a mother-tongue."

- Map of Major Zhuang language groups

- Paradisec has an open access collection of Zhuang Mogong Texts from Bama and Tianyang

- Sawcuengh People.com Official Zhuang language version (Standard Zhuang) of the People's Daily website