Urheimat

In historical linguistics, an Urheimat /ˈʊərhaɪmɑːt/ (from German ur- "original" and Heimat, home, homeland) is the area of origin of the speakers of a proto-language, the (reconstructed or known) parent language of a group of languages assumed to be genetically related.

Depending on the age of the language family under consideration, its homeland may be known with near-certainty (in the case of historical or near-historical migrations) or it may be very uncertain (in the case of deep prehistory). The reconstruction of a prehistorical homeland makes use of a variety of disciplines, including archaeology and archaeogenetics.

Limitations of the concept

The concept of a (single, identifiable) "homeland" of a given language family implies a purely genealogical view of the development of languages. This assumption is often reasonable and useful, but it is by no means a logical necessity, as languages are well known to be susceptible to areal change such as substrate or superstrate influence.

Time depth

Over a sufficient period of time, in the absence of evidence of intermediary steps in the process, it may be impossible to observe linkages between languages that have a shared Urheimat: given enough time, natural language change will obliterate any meaningful linguistic evidence of a common genetic source. This general concern is a manifestation of the larger issue of "time depth" in historical linguistics.[1]

For example, the languages of the New World are believed to be descended from a relatively "rapid" peopling of the Americas (relative to the duration of the Upper Paleolithic) within a few millennia (roughly between 20,000 and 15,000 years ago),[2] but their genetic relationship has become completely obscured over the more than ten millennia which have passed between their separation and their first written record in the early modern period. Similarly, the Australian Aboriginal languages are divided into some 28 families and isolates for which no genetic relationship can be shown.[3]

The Urheimaten reconstructed using the methods of comparative linguistics typically estimate separation times dating to the Neolithic or later. It is undisputed that fully developed languages were present throughout the Upper Paleolithic, and possibly into the deep Middle Paleolithic (see origin of language, behavioral modernity). These languages would have spread with the early human migrations of the first "peopling of the world", but they are no longer amenable to linguistic reconstruction. The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) has imposed linguistic separation lasting several millennia on many Upper Paleolithic populations in Eurasia, as they were forced to retreat into "refugia" before the advancing ice sheets. After the end of the LGM, Mesolithic populations of the Holocene again became more mobile, and most of the prehistoric spread of the world's major linguistic families seem to reflect the expansion of population cores during the Mesolithic followed by the Neolithic Revolution.

The Nostratic languages theory is the best-known attempt to expand the deep prehistory of the main language families of Eurasia (excepting Sino-Tibetan and the languages of Southeast Asia) to the beginning of the Holocene. First proposed in the early 20th century, the Nostratic theory still receives serious consideration, but it is by no means generally accepted. The more recent and more speculative ""Borean" hypothesis attempts to unite Nostratic with Dené–Caucasian and Austric, in a "mega-phylum" that would unite most languages of Eurasia, with a time depth going back to the Last Glacial Maximum.

The argument surrounding the "Proto-Human language", finally, is almost completely detached from linguistic reconstruction, instead surrounding questions of phonology and the origin of speech. Time depths involved in the deep prehistory of all the world's extant languages are of the order of at least 100,000 years.[4]

Language contact and creolization

The concept of an Urheimat only applies to populations speaking a proto-language defined by the tree model. This is not always the case.

For example, in places where language families meet, the relationship between a group that speaks a language and the Urheimat for that language is complicated by "processes of migration, language shift and group absorption are documented by linguists and ethnographers" in groups that are themselves "transient and plastic." Thus, in the contact area in western Ethiopia between languages belonging to the Nilo-Saharan and Afroasiatic families, the Nilo-Saharan-speaking Nyangatom and the Afroasiatic-speaking Daasanach have been observed to be closely related to each other but genetically distinct from neighboring Afroasiatic-speaking populations. This is a reflection of the fact that the Daasanach, like the Nyangatom, originally spoke a Nilo-Saharan language, with the ancestral Daasanach later adopting an Afroasiatic language around the 19th century.[5]

Creole languages are hybrids of languages that are sometimes unrelated. Similarities arise from the creole formation process, rather than from genetic descent.[6] For example, a creole language may lack significant inflectional morphology, lack tone on monosyllabic words, or lack semantically opaque word formation, even if these features are found in all of the parent languages of the languages from which the creole was formed.[7]

Isolates

Some languages are language isolates. That is to say, they have no well accepted language family connection, no nodes in a family tree, and therefore no known Urheimat. An example is the Basque language of Northern Spain and south west France. Nevertheless, it is a scientific fact that all languages evolve. An unknown Urheimat may still be hypothesized, such as that for a Proto-Basque, and may be supported by archaeological and historical evidence.

Sometimes relatives are found for a language originally believed to be an isolate. An example is the Etruscan language, which, even though only partially understood, is believed to be related to the Rhaetic language and to the Lemnian language. A single family may be an isolate. In the case of the non-Austronesian indigenous languages of Papua New Guinea and the indigenous languages of Australia, there is no published linguistic hypothesis supported by any evidence that these languages have links to any other families. Nevertheless, an unknown Urheimat is implied. The entire Indo-European family itself is a language isolate: no further connections are known. This lack of information does not prevent some professional linguists from formulating additional hypothetical nodes (Nostratic) and additional homelands for the speakers.

Indo-European

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Philology

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe

Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians

East Asia Europe East Asia Europe

Indo-Aryan Iranian

|

|

Religion and mythology

Indo-Aryan Iranian Others Europe

|

|

The most widely accepted proposal to identify the Proto-Indo-European homeland is the steppe hypothesis, which puts the PIE homeland in the Pontic-Caspian steppe around 4,000 BC.[8][9][10][11][12] A minority support the Anatolian hypothesis, which puts it in Anatolia around 8,000 BC.[8][13][14][15] A notable third possibility is the Armenian hypothesis which situates the homeland south of the Caucasus. Several other explanations have been proposed, including the Neolithic creolisation hypothesis, Paleolithic Continuity Theory, and Indigenous Aryans or "Out of India" theory.[note 1]

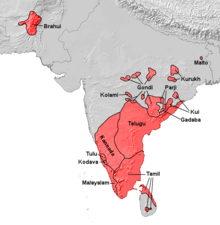

Dravidian

The Dravidian languages have been found mainly in South India since at least the second century BCE,[18] but Dravidian speakers may have been more widespread throughout India, including the northwest region,[19] before the arrival of Indo-European speakers.

Kolipakam et al. (2018) estimate the Dravidian language family to be approximately 4,500 years old.[20] According to Krishnamurti, linguistic evidence suggests that the South Dravidian language group had separated from a Proto-Dravidian language around 1100 BCE.[21] Russian linguist M.S. Andronov puts the split between Tamil (a written Southern Dravidian language) and Telugu (a written Central Dravidian language) between 1500 BCE and 1000 BCE.[22]

Hypotheses regarding the original homeland have centered on the Indus Valley Civilization. According to Asko Parpola, the Indus sign system represented an ancient Dravidian language.[23] In the 1970s David McAlpin proposed the Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis, suggesting an origin in Elam, whose Elamite language was spoken in the hills to the east of the ancient Sumerian civilization with whom the Indus Valley Civilization traded and shared domesticated species. This theory is mostly rejected.

Mongolic

Some historians suggest that the people associated with the Slab Grave culture were the direct ancestors of the Mongols.[24] Slab Grave cultural monuments are found in Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, Northwest China (Xinjiang and Qilian Mountains etc.), Northeast China, Lesser Khingan Mountains and southern Siberia. The identity of the ethnic core of Xiongnu has been a subject of varied hypotheses and some scholars insisted on a Mongolic origin.[25] Xiongnu Empire (209 BCE – 93 CE) became a dominant power on the steppes of Central Asia. They were active in regions of what is now southern Siberia, Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, Gansu and Xinjiang Province. Genghis Khan, starting around 1206 CE, waged a series of military campaigns that, together with campaigns by his successors, stretched from present-day Poland in the west to Korea in the east and from Siberia in the north to the Gulf of Oman and Vietnam in the south, after which the empire ultimately collapsed with little long lasting linguistic impact outside the core Mongolian area.[26] Unlike the Mongol Empire, which eventually withdrew back to its original Urheimat, the Turkic migrations shifted the Turkic center of population and power westward to the Black Sea region.

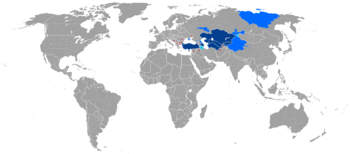

Turkic

There is considerable dispute over the time and place of origin of the Turkic languages, with candidates for their ancient homeland ranging from the Transcaspian steppe to Manchuria in Northeast Asia and South-Central-Siberia.[27][28][29] The lack of written records prior to the earliest Chinese accounts, and the fact that the early Turkic peoples were nomadic pastoralists, and hence mobile, makes localizing and dating the earliest homeland of the Turkic language difficult. Attempts to localize the proto-Turkic Urheimat are usually connected with the early archaeological horizon of west and central Siberia and in the region south of it.[30]

The Turkic peoples lived in the Eurasian Steppe including North China, especially Xinjiang Province, Inner Mongolia, Mongolia and West Siberian Plain possibly as far west as Lake Baikal and the Altai Mountains, by the 6th century CE. After Turkic migration, by the 10th century CE, most of Central Asia, formerly dominated by Iranian peoples, was settled by Turkic tribes. Then, the Seljuk Turks from the 11th century invaded Anatolia, ultimately resulting in permanent Turkic settlement there and the establishment of the Turkish nation. The Turkic languages are now spoken in Turkey, Iran, Central Asia and Siberia.

The inferred population genetic contributions of Turkic populations show a cline from a high point in the East to the a low point in the West.[31] In Turkey, the Central Asian contribution to the local population genetic mix is about 30%.[32]

Korean

The Korean language is spoken in Korea and among emigrants from Korea. Conservative historical linguists tend to classify the Korean language as a language isolate, although other suggest a relationship to the proposed Altaic language family or to Japonic languages.

Old Korean is attested in Chinese histories, in the Three Kingdoms period of Korea (ca. 0 to 900 CE), when the Silla Kingdom (in Eastern Korea), Baekje Kingdom (in Southwestern Korea), and Goguryeo Kingdom (in Northern Korea) were simultaneously present on the Korean peninsula, although Korean was not a literary language until later; the hangul script of Korean was invented in the 15th century CE (the earlier Idu script dates to the 6th century CE).

There was a group of similar languages called the Koguryoic languages in the northern Korean Peninsula and southern Manchuria, which included, according to Chinese records, the languages of Buyeo, Goguryeo, Baekje, Dongye, Okjeo—and possibly Gojoseon, but was different from ancient Tungusic languages like Mohe. Gojoseon was a kingdom in Northern Korea that is said by tradition to have been founded in 2333 BC (archaeological evidence and Chinese histories support a cultural civilization from around 1500 BCE and a kingdom fused from a federation of smaller states around the 7th century BCE), that was conquered by Han Dynasty China in 108 BC, and re-emerged from Chinese rule as the Kingdom Buyeo. The Three Kingdoms era kingdoms of Goguryeo and Baekje were successors to the Kingdom of Buyeo. Dongye was a vassal state of Goguryeo in Northeast Korea founded in the 3rd-century BCE that was eventually absorbed by Goguryeo around the 5th century CE. Okjeo was a minor state in Northern Korea to the North of Dongye that was a subordinate unit of Gojoseon from the 3rd century BCE to 108 BCE, then came under Han rule, and then was a subordinate state of Goguryeo. None of these Buyeo language family kingdoms ever included the Kingdom of Silla, which was just a small kingdom on the Southern coast of Korea until the Three Kingdoms period during which it expanded and conquered the other two kingdoms.

Linguists including Christopher Beckwith argue for Japanese as a descendant of Goguryeo, and for Korean as a descendant of the Silla language, based on lexical similarities between Goguryeo and Japanese, and based upon Silla's ultimate triumph in the quest for political control of Korea. Other linguists, including Kim Banghan, Alexander Vovin, and J. Marshall Unger argue that Japanese is related to the pre-Goguryeo language of the central and southern part of Korean peninsula, including what would become the Kingdom of Silla, and that Old Korean is Goguryeo with a pre-Goguryeo Japonic substrate, in part, because Japanese-like toponyms found in the historical homeland of Silla were also distributed in southern part of Korean peninsula, and are not found in the northern part of Korean peninsula or south-western Manchuria.[33] None of the extinct languages is attested in writing well enough to reach definitive conclusions resolving the debate.

Japonic

The Japonic languages are spoken in Japan and among emigrants from Japan and is attested in Japanese language writing from the 8th century CE, and in imperfect Chinese transcriptions from the late 5th century CE. Conservative historical linguists tend to classify a small number of Japanese languages as a language family of their own. The Ainu languages are a barely surviving family of languages or dialects that are spoken by indigenous populations on the island of Hokkaidō in what is now northern Japan.

There are similarities between the Japanese language and the Korean language in lexicon and grammatical features, but there is dispute over whether these denote a common origin, or mere linguistic borrowing due to a sprachbund of neighboring languages that are adjacent to each other. Samuel E. Martin, Roy Andrew Miller, and Sergei Starostin are linguists who have argued that they have common origins.[34][35][36][37][38] In contrast, Alexander Vovin has argued for a regional borrowing model to explain the linguistic similarities.[39]

One hypothesis proposes that Japanese is a relative of the extinct languages spoken by the Buyeo-Goguryeo cultures of Korea, southern Manchuria, and Liaodong of which the best attested is the extinct language Goguryeo.[40][41][42] This proposal is attributed to Shinmura Izuru, who proposed it in 1916. Modern Korean, in contrast, according to proponents of this hypothesis, appears to have stronger connections to the Silla language, spoken in the ancient kingdom of Silla (57 BCE – 935 CE), one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, whose similarity to the Goguryeo language is not clearly established.

The earliest Chinese historical records concerning the "Wa" in Japan indicate that they were fractured into many warring states. But, modern Japanese dialects show a common origin, rather than a "bushy" one. So, it is possible that there were many Yayoi dialects in the period before Old Japanese emerged, of which the dialect of the warring states that ended up prevailing politically as the Japanese state was unified superseded other early Yayoi languages or dialects.[43]

After a new wave of immigration, probably from the Korean Peninsula some 2,300 years ago, of the Yayoi people, the Jōmon were pushed into northern Japan. Genetic data suggest that modern Japanese are descended from both the Yayoi and the Jōmon. Tradition, as documented by the Nihon Shoki, a legendary account of Japan's history, puts the date of the Yayoi arrival in Japan at 660 BCE. Chinese historical records mention the existence of the Yayoi (called "Wa") starting in 57 BCE. The existing Japanese language has its origins at approximately this point in time, if not earlier (to the extent that Japanese derives primarily from either the language of the Bronze Age Yayoi people, as it existed prior to their arrival in Japan, or derives primarily from a language of the Jōmon at that point in time, rather than being a creole of some sort). Skeletal remains suggests that the two cultures had fused into a group with a homogeneous physical appearance in Southern Japan by 250 CE.[43] It is possible that the Japanese language has roots related to the Ainu language, the historical language of the Yayoi, whatever that may have been, or could have been a creole of both. It is also possible the Japanese language has roots in a language spoken in Southern Japan that is lost and now unknown.[43]

The Ainu people are genetic descendants of the Jōmon, with some contribution from the Okhotsk people.[44] The Ainu languages that are now spoken by Ainu minorities in Hokkaidō; and were formerly spoken in southern and central Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands (an area also known as Ezo), and perhaps northern Honshū island by the Emishi people (until approximately 1000 CE), are associated with the founding Jōmon people of Japan from than 14,000 years ago or earlier, and the Satsumon culture of Hokkaidō, although the Ainu also had contact with the Paleo-Siberian Okhotsk culture whose modern descendants include the Nivkh people (whose original homeland was mostly occupied by the Tungusic peoples), which could have linguistically influenced the Ainu language.[45] Thus, as a result of this important outside cultural influence, it is impossible to know with certainty how similar the language of the original language of the Jōmon people was to that spoken by the Ainu people today. Some linguists have suggested other language family connections for the Ainu language: Shafer has suggested a distant connection to the Austroasiatic languages.[46] Vovin, had viewed that suggestion as merely preliminary.[47] Japanese linguist Shichirō Murayama tried to link Ainu to the Austronesian languages, which include the languages of the Philippines, Taiwan, and Indonesia through both vocabulary and cultural comparisons. There is no consensus, however, that the Ainu languages have sources in any other known language, and the unique population genetics of the Ainu people support the hypothesis that they were largely isolated from the rest of the world for many thousands of years.

The Yayoi people had strong physical, genetic and cultural similarities to the Chinese during the Western Han Dynasty (202 BCE- 9 CE) in the Jiangsu province on China's Eastern Coast.[48] The Yayoi also have strong cultural similarities to the Koreans of that time period.[43][49]

Some linguists, such as Turchin,[50] see a connection between Japanese and Korean and an Altaic language family or similar larger grouping of languages, with those speakers coming from an area North of Korea, based in part upon similarities in lexical roots. The statistical method used by Turchin, however, would not discriminate between Jōmon and Yayoi sources for any Altaic linguistic affinities. Turchin's analysis also did not look at the various proposed ancient predecessors of the Korean language in Korea or the relationship of those languages to any of the proto-Altaic languages, despite the fact that the hypothesis would require one of those ancient Korean peninsular languages to be intermediate between Japanese and one of the proto-Altaic languages. Old Japanese when first attested had eight vowels, rather than the current five (which were lost within a century of the oldest preserved writings) which was close to the vowel system seen in Uralic and Altaic languages.[51] Old Japanese also had more grammatical similarity to Altaic languages than modern Japanese.

These classifications of the origins of Japanese language origins ignore significant borrowing from other languages in recent times. Current estimates are that "wago" (i.e. words attributable to the original Yayoi language) make up 33.8% of the Japanese lexicon, that "kango" (i.e. words with roots borrowed from Chinese since the 5th century CE) make up 49.1% of Japanese words (and in addition, the Chinese ideograms used in the Japanese written language), that foreign words called gairaigo make up 8.8% of Japanese words, and that 8.3% of Japanese words are konshugo that draw upon multiple languages.[52] This account attributes only a small number of words in modern Japanese to Ainu roots.

The six Ryukyuan languages spoken in the islands to the South of Japan, are descended from Proto-Japonic but are not mutually intelligible with Japanese with which they share about 72% of their words (or each other) and started to diverge from Japanese around the 7th century CE. These islands were united in a Ryukyuan kingdom from 1429 CE (prior to that there were multiple divided kingdoms which were tributary states of China after 1372 CE); the kingdom was a tributary state of China until 1609 when it became a vassal state of Japan, until it was annexed by Japan in 1879. These languages were then suppressed and while they have about a million native speakers, there are relatively few native speakers under the age of twenty. They are effectively minority languages at this point due to the government's recognition of them as dialects.

Uralic

The Uralic homeland is unknown. A possible focus is the Comb Ceramic Culture of ca 4200 – ca 2000 BCE (shown on the map to the right). This is suggested by the high language diversity around the middle Volga River, where three highly distinct branches of the Uralic family, Mordvinic, Mari, and Permic, are located. Reconstructed plant and animal names (including spruce, Siberian pine, Siberian Fir, Siberian larch, brittle willow, elm, and hedgehog) are consistent with this location. This is adjacent to the proposed homeland for Proto-Indo-European under the Kurgan hypothesis.

French anthropologist Bernard Sergent, in La Genèse de l'Inde (1997), argued that Finno-Ugric (Uralic) may have a genetic source or have borrowed significantly from proto-Dravidian or a predecessor language of West African origins. Some linguists see Uralic (Hungarian, Finnish) as having a linguistic relationship to both Altaic (Turkic, Mongol) language groups[54] (as in the outdated Ural-Altaic hypothesis) and Dravidian languages. The theory that the Dravidian languages display similarities with the Uralic language group, suggesting a prolonged period of contact in the past,[55] is popular amongst Dravidian linguists and has been supported by a number of scholars, including Robert Caldwell,[56] Thomas Burrow,[57] Kamil Zvelebil,[58] and Mikhail Andronov.[59] This theory has, however, been rejected by some specialists in Uralic languages,[60] and has in recent times also been criticised by other Dravidian linguists like the late Bhadriraju Krishnamurti.[61]

As noted below, many notable linguists have proposed that the Eskimo-Aleut languages and Uralic languages have a common origin, although there is no consensus that this connection is genuine. A genetic relationship between Uralic and the Indo-European languages has also been proposed (see Indo-Uralic languages).

Yeniseian

The Yeniseian language family has been recently tied by linguist Edward Vajda to the Native American Na-Dene languages of North American (e.g. Navajo),[62] in a proposal named Dene-Yeniseian. Several well-known linguists have reviewed the hypothesis as favorable, although several linguists, such as Lyle Campbell, still reject it. This family of languages is sometimes described as Paleosiberian, a classification that rests on a belief that it represents a stratum of Siberian populations that preceded the speakers of the other modern languages of Siberia (mostly of the Indo-European and Altaic language families), possibly one that dates back to the Paleolithic era when North America was initially populated. However, Paleosiberian is usually considered a – negatively defined – collective term of convenience, not a genetic nor even areal grouping, similarly to Papuan. There is some evidence that the speakers of the Yeniseian languages (such as the Ket language, which is the only surviving member of the moribund language family) migrated to their current homeland along the Yenisei River in Central Siberia from an area south of the Altai Mountains in the general vicinity of Mongolia or Northwest China within the last 2500 years or so (although there is no evidence that the Yeniseian languages are linguistically related to the Altaic languages).[63][64][65] One sentence of the language of the Jie, a Xiongnu tribe who founded the Later Zhao state in Chinese history, appears consistent with being a Yeniseian language. Other linguists have suggested, with far less widespread acceptance in the linguistics community, that the Yeniseian languages have a genetic relationship to one or more of the Caucasian languages and the Sino-Tibetan languages (such as Chinese).[66][67]

Eurasian language isolates

There are languages which are predominantly found in Europe, North Asia and South Asia and are not part of the language families above. First, the Basque language spoken in Northern Spain and Southwestern France. Second, the three living language families of the Caucasus mountains (Northwest Caucasian, Northeast Caucasian, and South Caucasian/Kartvelian, with the first two sometimes proposed as members of a single North Caucasian language family). Third, the Paleosiberian languages (the Yukaghir languages of Central Siberia, viewed by some linguists as a divergent branch of the Uralic languages,[68][69] and the Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages of Eastern Siberia, a grouping which sometimes includes Yenesian language and the geographically adjacent, although sometimes treated as a language isolate, Nivkh language). And fourth, a few South Asian linguistic isolates, such as Burushaski, spoken mostly in isolated pockets of Northern Pakistan, and the two indigenous language families of the Andamanese people (Great Andamanese and Ongan) and perhaps Nihali (spoken in West Central India).[70] In each of these cases, the languages are spoken in an area that is geographically compact, were spoken in that area at the time that they were first attested historically, and there is no definitive evidence of an origin for the languages in question outside the area where they are spoken now.

Joseph Greenberg and Stephen Wurm have both noted lexical similarities between the Great Andamanese language and the West Papuan languages. Wurm noted that the lexical similarities "are quite striking and amount to virtual formal identity [...] in a number of instances." There is no agreement, even between these two linguists, on a narrative that gave rise to these similarities.

Michael Fortescue, a specialist in Eskimo–Aleut as well as in Chukotko-Kamchatkan, argues for a link between Uralic, Yukaghir, Chukotko-Kamchatkan, and Eskimo–Aleut in Language Relations Across Bering Strait (1998). He calls this proposed grouping Uralo-Siberian.

There have been determined efforts by multiple linguists from at least the 19th century to link these languages to other language families, particularly in the case of the Basque language, where numerous connections to language families living and dead have been proposed by linguists. Frequently, efforts to look for deeper linguistic origins of these languages will also attempt to integrate them into attested extinct languages of Europe, such as the Etruscan language of Northern Italy, the Ligurian language of Italy, the Lemnian language of the Aegean Island of Lemnos, the Minoan language aka Linear A of ancient Crete, the Sumerian language once spoken in Mesopotamia (which is the oldest attested written language), the language of the Indus River Valley civilization, the Elamite language of Iran, and the Hurrian language and Hattic language of Anatolia. None of these efforts has achieved wide support among linguists, although some have been viewed as sufficiently credible to receive serious consideration from multiple linguists.[70][71][72][73][74][75]

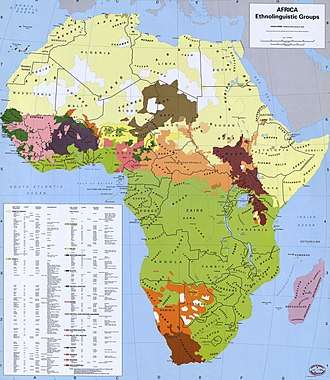

Khoisan

The Khoisan click languages of Africa do not form a language family and so do not, as a family, have a homeland. However, limited genetic evidence from some Khoisan-language speakers in southern Africa suggest an origin "along the African rift and a possible wider East African range."[76] Thus, the Bushmen of the Kalahari who occupy the largest geographic region where click languages are spoken are viewed as a relict population far removed from the place where click languages probably originated. The Khoe languages, Tuu languages, Kx'a languages, Hadza language and Sandawe language (the latter two being Tanzanian language isolates) are frequently grouped together in the catch all Khoisan categorization, despite the lack of a definitive recent common origin of these languages in a common language family. However, for the Khoe-Kwadi group, a more recent origin by immigration from East Africa (around the beginning of the Christian Era) has been suggested by Tom Güldemann, based on his observation of similarities with Sandawe.

Afro-Asiatic

The Afro-Asiatic languages include Arabic, Hebrew, Berber, and a variety of other languages now found mostly in Northeast Africa, although the exact boundaries of this language family are disputed in the case of a small number of languages spoken by small numbers of individuals in a few localized areas of Sudan and East Africa.

The limited area of the Afro-Asiatic Sprachraum (prior to its expansion to new areas in the historic era) has limited the potential areas where that family's Urheimat could be. Generally speaking, two proposals have been developed: that Afro-Asiatic arose in a Semitic Urheimat in the Middle East aka Southwest Asia, or that Afro-Asiatic languages arose in northeast Africa (generally, either between Darfur and Tibesti or in Ethiopia and the other countries of the Horn of Africa). The African hypothesis is considered to be rather more likely at the present time, because of the greater diversity of languages with more distant relationships to each other there.

There have been serious linguistic proponents of almost every conceivable possible set of relationships of the Afro-Asiatic language subfamilies to each other, although there is reasonably great consensus concerning the subfamily classification of all but a few of the Afro-Asiatic languages. Some of this difficulty in resolving the Afro-Asiatic family tree flows from the time depth of these languages. The Afro-Asiatic Egyptian language of ancient Egypt (whose latest stage is known as Coptic) is one of the two oldest written languages on Earth (the other being the Sumerian language, a language isolate) dating in written form to approximately 3000 BCE, and the Semitic Akkadian language was also attested in writing from a very early date (ca. 2000 BCE). A common Afro-Asiatic proto-language is necessarily older than these very old written languages which belonged to language families that had already diverged from each other considerably by that point. There is also no one genetic profile that is uniform among Afro-Asiatic language speakers that clearly unites them. There are also competing theories on whether the Afro-Asiatic language family owes its expansion to the Neolithic revolution that originated in an area that includes the range of the Afro-Asiatic language, or was already widespread in the Upper Paleolithic era.

Semitic

There has been speculation regarding the specific Semitic subfamily of Afro-Asiatic languages, again with the Horn of Africa and Southwest Asia—specifically the Levant—being the most common proposals. The large number of Semitic languages present in the Horn of Africa seems at first glance to support the hypothesis that the Semitic homeland lies there. However, the Semitic languages in the Horn of Africa all belong to the South Semitic subfamily and appear to all have relatively recent common origins in a single Ethio-Semitic proto-language, while the East and Central Semitic languages are native solely to Asia. These features, and the presence of certain common Semitic lexical items in all Ethio-Semitic languages referring to items that arrived in Africa from the Levant at a time after Semitic languages were known to have been spoken in the Levant, have lent weight to the Levantine proposal.

Hebrew is relatively closely related to the Arabic language even within the Semitic language family, being part of the same Central Semitic group.

The Maltese language, the only other Semitic language of Europe, is a derivative of the Arabic language as it was spoken in Sicily starting sometime after the rise of the Islamic empire in North Africa.

Nilo-Saharan

Genetic studies of Nilo-Saharan-speaking populations are in general agreement with archaeological evidence and linguistic studies that argue for a Nilo-Saharan homeland in eastern Sudan before 6000 BCE, with subsequent migration events northward to the eastern Sahara, westward to the Chad Basin, and southeastward into Kenya and Tanzania.[77]

Linguist Roger Blench has suggested that the Nilo-Saharan languages and the Niger–Congo languages may be branches of the same macro–language family.[78][79] Earlier proposals along this line were made by linguist Edgar Gregersen in 1972.[80] These proposals have not reached a linguistic consensus, however, and this connection presupposes that all of the Nilo-Saharan languages are actually related in a single family, which has not been definitively established.

Razib Khan, based on analysis of the autosomal genetics of the Tutsi ethnic group of Africa, suggests that "the Tutsi were in all likelihood once a Nilotic speaking population, who switched to the language of the Bantus amongst whom they settled."[81][82]

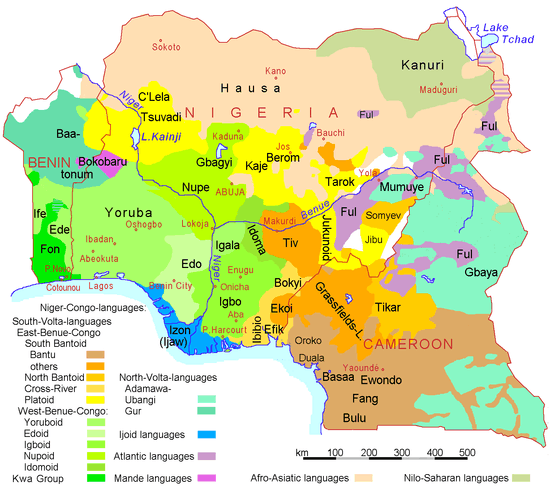

Niger–Congo

The homeland of the Niger–Congo languages, which has as its subfamily the Benue–Congo languages, which in turn includes the Bantu languages, is not known in time or place, beyond the fact that it probably originated in or near the area where these languages were spoken prior to Bantu expansion (i.e. West Africa or Central Africa) and probably predated the Bantu expansion of ca. 3000 BCE through 500 CE by many thousands of years.[83][84] Its expansion may have been associated with the expansion of Sahel agriculture in the African Neolithic period.[83]

According to linguist Roger Blench, as of 2004, all specialists in Niger–Congo languages believe the languages to have a common origin, rather than merely constituting a typological classification, for reasons including their shared noun-class system, their shared verbal extensions and their shared basic lexicon.[85][86] Similar classifications have been made ever since Diedrich Westermann in 1922.[87] Joseph Greenberg continued that tradition making it the starting point for modern linguistic classification in Africa, with some of his most notable publications going to press starting in the 1960s.[88] But, there has been active debate for many decades over the appropriate subclassifications of the languages in that language family, which is a key tool used in localizing a language's place of origin.[85] No definitive "Proto-Niger–Congo" lexicon or grammar has been developed for the language family as a whole.

An important unresolved issue in determining the time and place where the Niger–Congo languages originated and their range prior to recorded history is this language family's relationship to the Kordofanian languages now spoken in the Nuba mountains of Sudan, which is not contiguous with the remainder of the Niger–Congo language speaking region and is at the northeasternmost extent of the current Niger–Congo linguistic region. The current prevailing linguistic view is that Kordofanian languages are part of the Niger–Congo language family, and that among the many languages still surviving in that region these may be the oldest.[89] The evidence is insufficient to determine if this outlier group of Niger–Congo language speakers represent a prehistoric range of a Niger–Congo linguistic region that has since contracted as other languages have intruded, or if instead, this represents a group of Niger–Congo language speakers who migrated to the area at some point in prehistory where they were an isolated linguistic community from the beginning.

The prehistoric range for the Niger–Congo languages has implications, not just for the history of the Niger–Congo languages, but for the origins of the Afro-Asiatic languages and Nilo-Saharan languages whose homelands have been hypothesized by some to overlap with the Niger–Congo linguistic range prior to recorded history. If the consensus view regarding the origins of the Nilo-Saharan languages which came to East Africa is adopted, and a North African or Southwest Asian origin for Afro-Asiatic languages is assumed, the linguistic affiliation of East Africa prior to the arrival of Nilo-Saharan and Afro-Asiatic languages is left open. The overlap between the potential areas of origin for these languages in East Africa is particularly notable because includes the regions from which the Proto-Eurasians who brought anatomically modern humans Out of Africa, and presumably their original proto-language or languages originated.

However, there is more agreement regarding the place of origin of the Benue–Congo subfamily of languages, which is the largest subfamily of the group, and the place of origin of the Bantu languages and the time at which it started to expand is known with great specificity.

The classification of the relatively divergent family of Ubangian languages which are centered in the Central African Republic, as part of the Niger–Congo language family where Greenberg classified them in 1963 and subsequently scholars concurred,[90] was called into question, by linguist Gerrit Dimmendaal in a 2008 article.[91]

Benue-Congo

Roger Blench, relying particularly on prior work by Professor Kay Williamson of the University of Port Harcourt, and the linguist P. De Wolf, who each took the same position, has argued that a Benue–Congo linguistic subfamily of the Niger–Congo language family, which includes the Bantu languages and other related languages and would be the largest branch of Niger–Congo, is an empirically supported grouping which probably originated at the confluence of the Benue and Niger Rivers in Central Nigeria.[85][92][93][94][95][96] These estimates of the place of origin of the Benue-Congo language family do not fix a date for the start of that expansion other than that it must have been sufficiently prior to the Bantu expansion to allow for the diversification of the languages within this language family that includes Bantu.

There is a widespread consensus among linguistic scholars that Bantu languages of the Niger–Congo family have a homeland near the coastal boundary of Nigeria and Cameroon, prior to a rapid expansion from that homeland starting about 3000 BCE.[77][83][97][98][99][100][101]

Linguistic, archeological and genetic evidence also indicates that during the course of the Bantu expansion, "independent waves of migration of western African and East African Bantu-speakers into southern Africa occurred."[77] In some places, Bantu language, genetic evidence suggests that Bantu language expansion was largely a result of substantial population replacement.[102] In other places, Bantu language expansion, like many other languages, has been documented with population genetic evidence to have occurred by means other than complete or predominant population replacement (e.g. via language shift and admixture of incoming and existing populations). For example, one study found this to be the case in Bantu language speakers who are African Pygmies or are in Mozambique,[102] while another population genetic study found this to be the case in the Bantu language speaking Lemba of Zimbabwe.[103] Where Bantu was adopted via language shift of existing populations, prior African languages were spoken, probably from African language families that are now lost, except as substrate influences of local Bantu languages (such as click sounds in local Bantu languages).

Sino-Tibetan

The Sino-Tibetan Urheimat has been long debated with various scholars supporting an origin in North China, or in West China, or in the Himalayas. Population genetic evidence, favors an origin for Proto-Sino-Tibetan languages in the upper and middle Yellow River basin, with part of that source population branching off to settle in the Himalayas, with the split of the population that would provide the genesis of the Chinese language from the population that would provide the genesis of the larger Sino-Tibetan language family in the East Asian Neolithic era:[104]

"[T]he closest relatives of the Tibetans are the Yi people, who live in the Hengduan Mountains and were originally formed through fusion with natives along their migration routes into the mountains. The Tibetan and Yi languages belong to the Tibeto-Burman language group and their ancestries can be traced back to an ancient tribe, the Di-Qiang . . . After the ancestors of Sino-Tibetans reached the upper and middle Yellow River basin, they divided into two subgroups: Proto-Tibeto-Burman and Proto-Chinese. . . . The ancestral component which was dominant in Tibetan and Yi arose from the Proto-Tibeto-Burman subgroup, which marched on to south-west China and later, through one of its branches, became the ancestor of modern Tibetans. Proto-Tibeto-Burmans also spread over the Hengduan Mountains where the Yi have lived for hundreds of generations. Taking the optimal living condition and the easiest migration route into account, we favor the single-route hypothesis; it is more likely that their migration into the Tibetan Plateau through the Hengduan Mountain valleys occurred after Tibetan ancestors separated from the other Proto-Tibeto-Burman groups and diverged to form the modern Tibetan population."

According to the Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus project of the University of California at Berkeley (2011), the Proto-Sino-Tibetan (PST) homeland may have been in the general area in the east of the Tibetan Plateau. Regarding the time depth of Sino-Tibetan separation, they estimate an age of at least 6,000 years, comparable to the age of Proto-Indo-European.[105] Some scholars place the Tibeto-Burman homeland in the area encompassing western Sichuan, northern Yunnan and eastern Tibet.[106]

Another study also suggested the homeland of Sino-Tibetan in northern China near the Yellow River basin.[107] One of the earliest Neolithic cultures of China in the upper to middle Yellow River basin was the Peiligang culture of 7000 BCE to 5000 BCE, so the population genetic reference in the quoted material is to a date on or after this time period. The Neolithic era concluded in the Yellow River around 1500 BCE. This is not inconsistent with the linguistically based estimate from the Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus project. By the early and middle Zhou Dynasty (1122 BCE–256 BCE), the language spoken in the Zhou court had become the standardized dialect for that kingdom.[108]

In contrast, four of the other main language families of East Asia and Southeast Asia outside the Sino-Tibetan language family, Austroasiatic, Austronesian, Hmong–Mien and Kra-Dai, are generally believed to have at origins at some stage of their development in South China.

Austroasiatic

The homeland of the Austroasiatic languages (e.g. Vietnamese, Cambodian) which are found from Southeast Asia to India is hypothesized to be located in "the hills of southern Yunnan in China," between 4000 BCE and 2000 BCE,[109] with influences from Aryan and Dravidian languages at the Western edge of its expanse in India, and influence from Chinese at the Eastern edge of the regions where it is found. The disjoint distribution of Austroasiatic languages suggests that they were once spoken in most of the areas where the Kra–Dai languages (e.g. Thai, Lao) are now dominant.

However, Paul Sidwell has recently advocated a homeland in Southeast Asia instead,[110] preferring a late date of dispersal of about 2000 BCE.[111]

There is a strong correlation between the population genetic distribution Y-Chromosomal haplogroup O2a1-M95 and the distribution of Austroasiatic language speakers.[112]

Hmong–Mien

The most likely homeland of the Hmong–Mien languages (aka Miao–Yao languages) is in Southern China between the Yangtze and Mekong rivers, but speakers of these languages may have migrated from Central China either as part of the Han Chinese expansion or as a result of exile from an original homeland by Han Chinese.[113] Migration of people speaking these languages from South China to Southeast Asia took place ca. 1600–1700 CE. Ancient DNA evidence suggests that the ancestors of the speakers of the Hmong–Mien languages were a population genetically distinct from that of the Tai–Kadai and Austronesian language source populations at a location on the Yangtze River.[114] Recent Y-DNA phylogeny evidence supports the proposition that people who speak the Hmong-Mien languages are descended from the population that now speaks Austroasiatic Mon-Khmer languages.[115]

Austronesian

.png)

The homeland of the Austronesian languages is widely accepted by linguists to be in what is now Taiwan. On this island the deepest divisions in Austronesian are found, among the families of the native Formosan languages. According to Blust (1999), the Formosan languages form nine of the ten primary branches of the Austronesian language family. Comrie (2001:28) noted this when he wrote:

... the internal diversity among the... Formosan languages... is greater than that in all the rest of Austronesian put together, so there is a major genetic split within Austronesian between Formosan and the rest... Indeed, the genetic diversity within Formosan is so great that it may well consist of several primary branches of the overall Austronesian family.

Archaeological evidence (e.g., Bellwood 1997) suggests that speakers of pre-Proto-Austronesian spread from the South Chinese mainland to Taiwan at some time around 6000 BCE. Evidence from historical linguistics suggests that it is from this island that seafaring peoples migrated, perhaps in distinct waves separated by millennia, to the entire region encompassed by the Austronesian languages (Diamond 2000). It is believed that this migration began around 4000 BCE (Blust 1999). However, evidence from historical linguistics cannot bridge the gap between those two periods.

It is possible that the ancient Taiwan aborigines were related to the ancient Minyue, derived in ancient times from the southeast coast of Mainland China, as suggested by linguists Li Jen-Kuei and Robert Blust. It is suggested that in the southeast coastal regions of China, there were many sea nomads during the Neolithic era and they may have spoken ancestral Austronesian languages, and were skilled seafarers.

The specific origins of the most far flung member of this language family, the Malagasy language of Madagascar off the coast of Africa, are described above in the part of this article concerning African languages.

The Austro-Tai hypothesis suggests a common origin for the Austronesian languages and the Tai–Kadai languages whose hypothesized place of origin is geographically close to Taiwan.

The Malagasy language of Madagascar is not related to nearby African languages, instead being the westernmost member of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. The similarity between Malagasy and Malay and Javanese was noted as long ago as 1708 by the Dutch scholar Adriaan van Reeland.[116] Malagasy is related to the Malayo-Polynesian languages of Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines, and more closely with the Southeast Barito group of languages spoken in Borneo except for its Polynesian morphophonemics.[117]

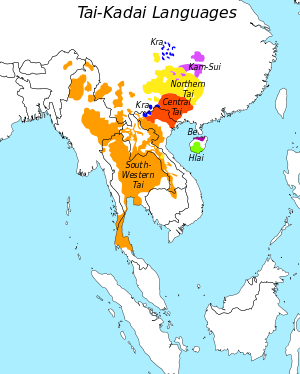

Kra–Dai

Many scholars have addressed the question of the origins of the Kra–Dai languages.[118][119][120][121][122]

There is a consensus that the Kra–Dai languages have their origins in Southern China or on major nearby islands (such as Taiwan or Hainan). The leading hypothesis is that the likely homeland of proto-Kra–Dai was coastal Fujian or Guangdong. The spread of the Kra–Dai peoples may have been aided by agriculture, but any who remained near the coast were eventually absorbed by the Chinese. Weera Ostapirat is one academic who articulates this position.[123]

Laurent Sagart, on the other hand, holds that Kra–Dai is a branch of Austronesian which migrated back to the mainland from northeastern Taiwan long after Taiwan was settled, but probably before the expansion of Malayo-Polynesian out of Taiwan.[124][125][126] The language was then largely relexified from what he believes may have been an Austroasiatic language. Sagart suggests that Austro-Tai is ultimately related to the Sino-Tibetan languages and has its origin in the Neolithic communities of the coastal regions of prehistoric North China or East China.

Ostapirat, by contrast, sees connections with the Austroasiatic languages (in Austric), as has Benedict.[127][128][129] Reid notes that the two approaches are not incompatible, if Austric is valid and can be connected to Sino-Tibetan.[130]

Robert Blust (1999) suggests that proto-Kra–Dai speakers originated in the northern Philippines and migrated from there to Hainan (hence the diversity of Kra–Dai languages on that island), and were radically restructured following contact with Hmong–Mien and Sinitic. However, Ostapirat maintains that Kra–Dai could not descend from Malayo-Polynesian in the Philippines, and likely not from the languages of eastern Taiwan either. His evidence is in the Kra–Dai sound correspondences, which reflect Austronesian distinctions that were lost in Malayo-Polynesian and even Eastern Formosan.

Genetic evidence corroborates evidence from Kadai speaking people's oral traditions that puts a Kadai homeland on Hainan.[131] Ancient DNA evidence also shows a connection between speakers of Kra–Dai speaking populations and Austronesian language speaking populations,[114] and a genetically distinct population at a different location on the Yangtze River as a possible source of Hmong–Mien languages.[114]

Oceania

The only language isolates or language families predominantly spoken in Southeast Asia, East Asia and Oceania that do not belong to one of the language families above are the indigenous languages of Melanesia (which number more than eight hundred or more in perhaps sixty language families), which are described with a geographic term that does not presume a genetic relationship between them as the Papuan languages, and the Australian aboriginal languages (of which there are about one hundred and fifty remaining in about ten language families, all of which, except the languages of the Pama–Nyungan languages are largely confined to the central Northern coast of Australia). No linguists have found a language family connection between indigenous Papuan and Australian aboriginal languages and those of Asia, Africa, the Americas or any other part of the world. Indeed, no linguistic connection has been established between the indigenous languages of Melanesia and the indigenous languages of the Aboriginal Australians.[132] This is consistent with the mainstream view, supported by population genetics and archaeology, that Papua New Guinea and Australia, as well as some of the islands neighboring Papua New Guinea, were first inhabited by hominins (humans or otherwise) at least 40,000 years ago in migrations that were either separate or swiftly segregated, and that many of these populations have had only limited contact with outside populations until the modern era. While there are plausible reasons to infer that the Melanesian languages and the aboriginal Australian languages, respectively, have common origins in a small founding population with a single language, the linguists have not been able to marshal lexical, phonetic and grammatical evidence from these languages in their current form to support these inferences.

Americas

Na-Dene

Since 2008, linguist Edward Vajda has been advocating, and attempting to demonstrate, a genetic link between the Na-Dene languages of North America and the Yeniseian languages of central Siberia, suggesting a homeland in Siberia or a back migration of Na-Dene speakers from Beringia. Na-Dene languages are spoken by Native Alaskans and some people from the First Nations of Western Canada, in the Pacific Northwest, and also includes the Southern Athabaskan languages spoken in the American Southwest (e. g., the languages Apache and Navajo).

Eskimo-Aleut

The Eskimo–Aleut languages are spoken by native peoples of the Arctic regions of Alaska and Canada and Greenland, generally to the North of Na-Dene linguistic areas (shown on the map on the left).

Current ancient and modern DNA scholarship and archaeology supports a three-layer paradigm in which first the Saqqaq (Arctic Paleo-Eskimos) which was present 2000 BCE, then the Dorset (second wave Arctic Paleo-Eskimos), and finally the Thule (proto-Inuit) from ca. 500 CE – 1000 CE, successively sweep Arctic North America while having little genetic impact on Native American populations further South, that presumably have origins that date back to the initial colonization of the Americas by modern humans from Asia (who are the first hominins to live there), and ancient DNA shows genetic continuity from the Thule to modern Inuit (whose genetics are remarkably homogeneous), dominated by the A2a, A2b, and D3 mtDNA haplotypes, while "Haplotype D2 (3%), found among modern Aleut and Siberian Eskimos, was identified at a low frequency in the modern samples but not the ancient. This haplotype was recently identified in an ancient Paleo-Eskimo Saqqaq individual from western Greenland. . . . Whole genomic sequencing of the 4,000-year-old PaleoEskimo, "Inuk," indicated that the Saqqaq sequences clustered with the Chukchi and Koryaks of Siberia-suggesting an earlier migration from Siberia along the northern slope of Alaska to Greenland."[133] Evidence such as bronze artifacts produced in East Asia from ca. 1000 CE, further supports a proto-Eskimo-Aleut arrival in the polar regions of North America ca. 500 CE – 1000 CE.[134]

The proto-Eskimo-Aleut migration to North America, associated with the Thule expansion in North America ca. 500 CE, took place much more recently than the initial human population of North America, which took place more than 14,000 years ago. Also, the modern Inuit populations are genetically distinct from other indigenous populations of the Americas. Thus, evidence from genetics and archaeology strongly supports an East Asian origin for Eskimo-Aleut languages sometime in the last 1500 years that is distinct from most other indigenous languages of the Americas. But there is no linguistic consensus on any particular languages of East Asia with which this family of North American languages is associated.[135] It is entirely possible that Eastern Siberian languages most closely ancestral to Eskimo-Aleut are extinct. Many indigenous languages and cultures of this region have died in the face of expanded Russian cultural and national influence starting in the 18th century.

Michael Fortescue in 1998 proposed a group of Uralo-Siberian languages, in which Uralic languages like Finnish were related to Eskimo-Aleut languages supported by lexical correspondences and grammatical similarities, expanding upon a proposal of Morris Swadesh in 1962 that itself reiterates similarities that have been noted since at least 1746.[136] Fortescue argues that the Uralo-Siberian proto-language (or a complex of related proto-languages) may have been spoken by Mesolithic hunting and fishing people in south-central Siberia (roughly, from the upper Yenisei river to Lake Baikal) between 8000 and 6000 BCE, and that the proto-languages of the derived families may have been carried northward out of this homeland in several successive waves down to about 4000 BCE, leaving the Samoyedic peoples in occupation of the Urheimat thereafter.

A 2005 proposal by Holst, also reiterating a proposal of Swadesh from 1962, suggests that the Wakashan languages (map on right) spoken in British Columbia around and on Vancouver Island, are part of the same language family as the Eskimo-Aleut languages.[137] This proposal, if accurate, would suggest that Na-Dene languages may have arrived in North America after (although not long after) Eskimo-Aleut languages.

Phonologically, the Eskimo–Aleut languages resemble other languages of northern North America and far eastern Siberia.

Uto-Aztecan

Some authorities on the history of the Uto-Aztecan language group place its homeland in the border region between the USA and Mexico, namely the upland regions of Arizona and New Mexico and the adjacent areas of the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua, shown on the map (below left) roughly corresponding to the Sonoran Desert. The proto-language would have been spoken by foragers, about 5,000 years ago. Hill (2001) proposes instead a homeland further south, making the assumed speakers of Proto-Uto-Aztecan maize cultivators in Mesoamerica, who were gradually pushed north, bringing maize cultivation with them, during the period of roughly 4,500 to 3,000 years ago, the geographic diffusion of speakers corresponding to the breakup of linguistic unity.[138]

Tupian

Tupian languages are predominantly spoken in eastern South America, Specially in Brazil and Paraguay with branches in neighboring countries. They are believed by some scholars to be related to Carib and Jê languages. Tupian was once spoken by the powerful Tupian nations of the coast, which the Europeans encountered. It is still spoken by some of the tribes of Xingu and the Guarani, and small nomadic peoples uncontacted in the Amazon. The language was adapted and used by the Bandeirantes who spent most of their lives among the natives. These armies of explorers and raiders from São Paulo explored the then unknown interior of Brazil in search of gold and slaves. They transformed the language in dialects that later become the Nhéngatu or Lingua Geral and made it the most widely spoken language in Brazil until the Marquis of Pombal imposed the use of Portuguese in the Colony. Many branches are probably lost or were never recorded as the Tupian peoples don't have a writing system. Some dialects were spoken by groups that were probably wiped out or enslaved by other groups or by the Bandeirantes. José de Anchieta a Canarian Jesuit priest active in the Brazilian coast during the early Portuguese settlement, Was the first person to write and translate the tupi language. Rodrigues (2007) considers the Proto-Tupian homeland to be somewhere between the Guaporé and Aripuanã rivers, in the Madeira River basin. Much of this area corresponds to the modern-day state of Rondônia, Brazil. Five of the 10 Tupian branches are found in this area, as well as some Tupi–Guarani languages (especially Kawahíb), making it the probable Urheimat of these languages and maybe of its speaking peoples. Rodrigues believes the Proto-Tupian language dates back to around 5,000 B.P.

Other groups

Other than Dene-Yeniseian, and a possible connection between the Eskimo-Aleut language family and the Uralic language family, no proposals of genetic relations between languages of North or South America and languages of Eurasia, Africa, or other parts of the world, have been backed by credible evidence. There is not, for example, any indication that the Vikings who had a brief presence in North America around 1000 CE left any linguistic trace.

Population genetic evidence suggests that the non-circumpolar indigenous peoples of the Americas have origins in a small common founder population in the Upper Paleolithic era that arrived via a Berginian land bridge from Asia.[139][140][141][142] This population genetic data point suggests the possibility that all indigenous Native American languages of non-circumpolar indigenous Americans (i.e. neither Inuit-Aleut nor Na-Dene) have genetic origins in a single language of the founding population of the Americas, and hence, as controversially proposed by Greenberg, that they all ultimately belong to the same linguistic superfamily, which Greenberg called Amerind.[143] But, there is not clear evidence of this from efforts to use traditional comparative linguistic methods to classify indigenous Native American languages. The process of identifying linguistic origins with traditional linguistic methods begins with the process of classifying languages into families.

In general, more progress has been made in identifying language family relationships in North America, where the just under three hundred attested languages are grouped into twenty-nine language families and twenty-seven language isolates (some of which are simply incapable of being classified because they are extinct and were not sufficiently well attested to classify). Two (super-) family proposals, Penutian and Hokan generally along the Pacific coast of North America that are gaining currency among linguists, would reduce the number of language families in North America to about fifteen. However, in large portions of the Southeast United States where it is known that there was considerable pre-Columbian linguistic diversity, there are no attested indigenous languages and the populations in question either left no survivors, or all remaining speakers of relocated tribes with diminished numbers underwent language shift as their ancestral languages became moribund.

Mesoamerica was home to one of the most developed successions of farming societies in the Americas in the pre-Columbian era. Mesoamerica's attested languages are likewise quite well systematized into six main language families and four other language isolates or small language families, as well as a few unclassified extinct languages, encompassing all of the languages in the region. Mesoamerica is also the only part of the Americas in which written languages were in use in the pre-Columbian era.

In South America there are about 350 living indigenous languages (in addition to many creoles) and an estimated more than one thousand extinct languages, grouped into more than 140 categories, only ten of which have more than five languages which have been demonstrated to belong to the same language family. This is about three times as much linguistic diversity at the language family/language isolate level as North America and Mesoamerica combined. The naïve expectation from population genetics would have been that there would be less linguistic diversity, because the entire indigenous population of South America appears to derive genetically from only a subset of an already small indigenous founder population of the Americas as a whole, something illustrated, for example, by its lack of several of the less common genetic haplotypes found in indigenous America outside South America (although genetic diversity has accumulated in these populations over time through mutations distinguishing these populations from the founder population genomes). Some of the lack of classification of indigenous South American languages may be simply attributable to the small number of linguists devoted to the task and the limited amount of information available about many of the languages. But the languages of the region may also simply be particularly diverse due to separation by great time depth and geographic isolation. The only other place in the world with comparable linguistic diversity that has not been reduced to a small number of language families is Papua New Guinea, which also experienced many millennia of isolation from the rest of the world that ended only relatively recently.

See also

References

- Renfrew, Colin; McMahon, April; Trask, Larry, eds. (1999). Time Depth in Historical Linguistics. ISBN 978-1-902937-06-9.

- O'Rourke, Dennis H.; Raff, Jennifer A. (2010), "The Human Genetic History of the Americas: The Final Frontier", Current Biology, 20 (4): R202–7, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.051, PMID 20178768

- Bowern, Claire; Atkinson, Quentin (2012). "Computational Phylogenetics and the Internal Structure of Pama-Nyungan". Language. 84 (4): 817–845. Kayser, Manfred (2010), "The Human Genetic History of Oceania: Near and Remote Views of Dispersal", Current Biology, 20 (4): R194–201, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.004, PMID 20178767

- Bengtson and Ruhlen (1994) offered a list of 27 "global etymologies". Bengtson, John D. and Merritt Ruhlen. 1994. "Global etymologies" Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. In Ruhlen 1994a, pp. 277–336. This approach has been criticized as flawed by Campbell and Poser (2008) who used the same criteria employed by Bengtson and Ruhlen to identify "cognates" in Spanish known to be false. Campbell, Lyle, and William J. Poser. 2008. Language Classification: History and Method. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 370–372.

- Poloni, ES; Naciri, Y; Bucho, R; Niba, R; Kervaire, B; Excoffier, L; Langaney, A; Sanchez-Mazas, A. (Nov 2009). "Genetic evidence for complexity in ethnic differentiation and history in East Africa". Ann Hum Genet. 73 (6): 582–600. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00541.x. PMID 19706029.

- McWhorter, J. H. (1998), "Identifying the Creole Prototype: Vindicating a Typological Class", Language, 74 (4): 788–818, doi:10.2307/417003, JSTOR 417003

- McWhorter, John H. (1999), "The Afrogenesis Hypothesis of Plantation Creole Origin", in Huber, Magnus; Parkvall, Mikael (eds.), Spreading the Word: The Issue of Diffusion among the Atlantic Creoles, London: Westminster University Press, pp. 111–152

- Mallory & Adams 2006.

- Anthony 2007.

- Pereltsvaig & Lewis 2015, pp. 1–16.

- Anthony & Ringe 2015.

- Haak W, Lazaridis I, Patterson N, Rohland N, Mallick S, Llamas B, Brandt G, Nordenfelt S, Harney E, Stewardson K, Fu Q, Mittnik A, Bánffy E, Economou C, Francken M, Friederich S, Garrido Pena R, Hallgren F, Khartanovich V, Khokhlov A, Kunst M, Kuznetsov P, Meller H, Mochalov O, Moiseyev V, Nicklisch N, L Pichler S, Risch R, A Rojo Guerra M, Roth C, Szécsényi-Nagy A, Wahl J, Meyer M, Krause J, Brown D, Anthony D, Cooper A, Werner Alt K, Reich D (11 June 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. bioRxiv 10.1101/013433. doi:10.1038/nature14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- Renfrew, Colin (1990). Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-38675-3.

- Gray & Atkinson 2003.

- Bouckaert et al. 2012.

- Jeffery D. Long, Historical Dictionary of Hinduism, Page 5

- Jeffery D. Long, Historical Dictionary of Hinduism, Page 6

- Inscriptions, ed. I. Mahadevan 2003

- "Dravidian languages." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 5 June 2008

- "Dravidian language family is approximately 4,500 years old, new linguistic analysis finds". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2018-05-17.

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77111-5. Lay summary – Frontline (Chennai) 20 (22) (October 25, 2003).

- Moorti, Etukoori Balaraama in Andhra Samkshipta Charitra. "Proto-Dravidian Study of Dravidian Linguistics and Civilization".

- Parpola, Asko. "Introduction to Study of the Indus Script". Harappa.com. Archived from the original on 2010-04-20. Retrieved 2010-03-01.

- Tumen D., "Anthropology of Archaeological Populations from Northeast Asia page 25,27

- Ts. Baasansuren "The scholar who showed the true Mongolia to the world", Summer 2010 vol.6 (14) Mongolica, pp.40

- Thomas T. Allsen – Culture and conquest in Mongol Eurasia.

- Yunusbayev, B. (2014). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads Across Eurasia". doi:10.1101/005850. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Römer, Claudia. Von den Hunnen zu den Türken – dunkle Vorgeschichte, in: Zentralasien. 13. bis 20. Jahrhundert. Geschichte und Gesellschaft, Wien 2006, p. 61

- Róna-Tas, András. "The Reconstruction of Proto-Turkic and the Genetic Question." In: The Turkic Languages, pp. 67–80. 1998.

- Róna-Tas, András. "The Reconstruction of Proto-Turkic and the Genetic Question." In: The Turkic Languages, pp. 67–80. 1998.

- Martínez-Cruz, Begoña; Vitalis, Renaud; Ségurel1, Laure; et al. (8 September 2010). "In the heartland of Eurasia: the multilocus genetic landscape of Central Asian populations". European Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (2): 216–23. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.153. PMC 3025785. PMID 20823912.

- Di Benedetto, G.; Ergüven, A. E.; Stenico, M.; Castrì, L.; Bertorelle, G.; Togan, I.; Barbujani, G. (2001). "DNA diversity and population admixture in Anatolia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 115 (2): 144–156. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.515.6508. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1064. PMID 11385601.

- Blažek, Václav. 2006. "Current progress in Altaic etymology." Linguistica Online, 30 January 2006

- Martin, Samuel E. (1966): Lexical Evidence Relating Japanese to Korean. Language 42/2: 185–251.

- Martin, Samuel E. (1990): Morphological clues to the relationship of Japanese and Korean. In: Philip Baldi (ed.): Linguistic Change and Reconstruction Methodology. Trends in Linguistics: Studies and Monographs 45: 483–509.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (1971): Japanese and the Other Altaic Languages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-52719-0.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (1996): Languages and History: Japanese, Korean and Altaic. Oslo: Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture. ISBN 974-8299-69-4.

- Sergei Starostin. Altaiskaya problema i proishozhdeniye yaponskogo yazika (The Altaic Problem and the Origins of the Japanese Language).

- Vovin, Alexander: Koreo-Japonica. University of Hawai'i Press. 2008.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. 2004. Koguryo: The Language of Japan's Continental Relatives: An Introduction to the Historical-Comparative Study of the Japanese-Koguryoic Languages. Leiden: Brill.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. 2006. "Methodological observations on some recent studies of the early ethnolinguistic history of Korea and vicinity." Altai Hakpo 16, 199–234.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. 2006b. "The ethnolinguistic history of the early Korean peninsula region: Japanese-Koguryoic and other languages in the Koguryo, Paekche, and Silla kingdoms." (page 33 ff.) Journal of Inner and East Asian Studies 2.2, 34–64.

- Diamond, Jared (June 1998). "Japanese Roots". Discover. 19 (6).

- Nakahori, Yutaka (2005). Y染色体からみた日本人 (Y Senshokutai kara Mita Nihonjin). Iwanami Science Library. ISBN 978-4-00-007450-6.

- Chaussonnet, Valerie (1995) Native Cultures of Alaska and Siberia. Page 35. Arctic Studies Center. Washington, D.C. 112p. ISBN 1-56098-661-1

- Shafer, R. (1965). "Studies in Austroasian II". Studia Orientalia 30 (5).

- Vovin, Alexander (1993). A Reconstruction of Proto-Ainu. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-09905-0.

- 渡来系弥生人の故郷を中国に求めて [Searching in China for the origin of the Yayoi people]. Long Journey to Prehistorical Japan (in Japanese). National Museum of Nature and Science (Japan). Archived from the original on 2015-04-21. Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- Mark J. Hudson (1999). Ruins of Identity Ethnogenesis in the Japanese Islands. University Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2156-4.

- Turchin, Peter; Peiros, Ilia; Gell-Mann, Murray. "Analyzing Genetic Connections between Languages by Matching Consonant Classes" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- 大野 晋 (1982)『仮名遣いと上代語』(岩波書店)p.65

- 新選国語辞典, 金田一京助, 小学館, 2001, ISBN 4-09-501407-5

- "Dravidian languages." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 30 Jun. 2008

- Tyler, Stephen (1968), "Dravidian and Uralian: the lexical evidence", Language, 44 (4): 798–812, doi:10.2307/411899, JSTOR 411899.

- Webb, Edward (1860), "Evidences of the Scythian Affinities of the Dravidian Languages, Condensed and Arranged from Rev. R. Caldwell's Comparative Dravidian Grammar", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 7: 271–298, doi:10.2307/592159, JSTOR 592159.

- Burrow, T. (1944), "Dravidian Studies IV: The Body in Dravidian and Uralian", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 11 (2): 328–356, doi:10.1017/s0041977x00072517.

- Zvelebil, Kamal (2006). Dravidian Languages. In Encyclopædia Britannica (DVD edition).

- Andronov, Mikhail S. (1971), "Comparative Studies on the Nature of Dravidian-Uralian Parallels: A Peep into the Prehistory of Language Families". Proceedings of the Second International Conference of Tamil Studies Madras. 267–277.

- Zvelebil, Kamal (1970), Comparative Dravidian Phonology Mouton, The Hauge. at p. 22 contains a bibliography of articles supporting and opposing the theory

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-77111-5.

- "Dene–Yeniseic Symposium, University of Alaska Fairbanks, February 2008". Archived from the original on 2009-05-26.

- Vovin, Alexander (2000). "Did the Xiong-nu speak a Yeniseian language?". Central Asiatic Journal. 44 (1): 87–104. JSTOR 41928223.

- Vovin, Alexander. (2002). 'Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language? Part 2: Vocabulary', in Altaica Budapestinensia MMII, Proceedings of the 45th Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Budapest, June 23–28, pp. 389–394.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2002). Central Asia and Non-Chinese Peoples of Ancient China. Variorum Collected Studies Series, 731. ISBN 978-0-86078-859-1.

- Starostin, Sergei A. (1991). On the Hypothesis of a Genetic Connection Between the Sino-Tibetan Languages and the Yeniseian and North Caucasian Languages. In Shevoroshkin (1991): 12–41. [Translation of Starostin 1984]

- Bengtson, John D. (1998). Caucasian and Sino-Tibetan: A Hypothesis of S. A. Starostin. General Linguistics, Vol. 36, no. 1/2, 1998 (1996). Pegasus Press, University of North Carolina, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Collinder, Björn. Jukagirisch und Uralisch ('Yukaghir and Uralic') 1940.)

- Collinder, Björn. 1965. An Introduction to the Uralic Languages. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1965.

- Trask, R.L. The History of Basque Routledge: 1997 ISBN 0-415-13116-2

- José Ignacio Hualde, Joseba Lakarra, Robert Lawrence Trask (1995), Towards a history of the Basque language, p. 81. John Benjamins Publishing Company, ISBN 90-272-3634-8.

- A Final (?) Response to the Basque Debate in Mother Tongue 1 (John D. Bengston)

- Theo Vennemann homepage

- J.P. Mallory, "In Search of the Indo-Europeans" (1989)

- Jubainville, H. D'Arbois de (1889, 1894). Les Premiers Habitants de l'Europe d'après les Écrivains de l'Antiquité et les Travaux des Linguistes: Seconde Édition. Paris: Ernest Thorin. pp. V.II, Book II, Chapter 9, Sections 10, 11. (French). Downloadable Google Books.

- Hammer MF, Karafet TM, Redd AJ, Jarjanazi H, Santachiara-Benerecetti S, Soodyall H, Zegura SL (2001). "Hierarchical Patterns of Global Human Y-Chromosome Diversity". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 18 (7): 1189–1203. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003906. PMID 11420360.

- Michael C. Campbell and Sarah A. Tishkoff, "The Evolution of Human Genetic and Phenotypic Variation in Africa," Current Biology, Volume 20, Issue 4, R166–R173, 23 February 2010

- Blench, Roger. KORDOFANIAN and Niger–Congo: NEW AND REVISED LEXICAL EVIDENCE" (Draft) (PDF).

- Blench, R.M. 1995, 'Is Niger–Congo simply a branch of Nilo-Saharan?' In: Proceedings of the Fifth Nilo-Saharan Linguistics Colloquium, Nice, 1992. ed. R. Nicolai and F. Rottland. 68–118. Köln: Rudiger Köppe.

- Gregersen, Edgar A (1972). "Kongo-Saharan". Journal of African Linguistics. 4: 46–56.

- Khan, Razib (August 29, 2011). "Tutsi probably differ genetically from the Hutu". Gene Expression. Discover. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- Khan, Razib (August 31, 2011). "Tutsi genetic, ii". Gene Expression. Discover. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- Jared Diamond, "Guns, Germs and Steel" (2000)

- Bostoen, Koen (2018-04-26). "The Bantu Expansion". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.191. ISBN 9780190277734.

- Blench, Roger (2004). THE BENUE-CONGO LANGUAGES: A PROPOSED INTERNAL CLASSIFICATION (Unpublished Working Draft) (PDF).

- See also Bendor-Samuel, J. ed. 1989. The Niger–Congo Languages. Lanham: University Press of America.

- Westermann, D. 1922a. Die Sprache der Guang. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.

- Greenberg, J.H. 1964. Historical inferences from linguistic research in sub-Saharan Africa. Boston University Papers in African History, 1:1–15.

- Herman Bell. 1995. The Nuba Mountains: Who Spoke What in 1976?. (The published results from a major project of the Institute of African and Asian Studies: the Language Survey of the Nuba Mountains.)