Kashgar

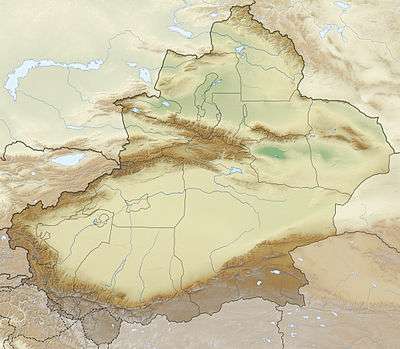

Kashgar[5][6][7] (Uyghur: قەشقەر ), also Kashi[7][8][9] (Chinese: 喀什), is an oasis city in Xinjiang. It is one of the westernmost cities of China, near the border with Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Pakistan. With a population of over 500,000, Kashgar has served as a trading post and strategically important city on the Silk Road between China, the Middle East and Europe for over 2,000 years.

Kashgar قەشقەر شەھرى · 喀什市 Shufu | |

|---|---|

Id Kah Mosque square | |

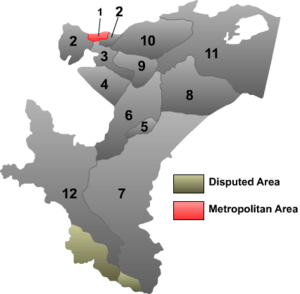

Location (red, labelled '1') within Kashgar Prefecture | |

Kashgar Location of the city center in Xinjiang | |

| Coordinates (Kashgar municipal government): 39°28′05″N 75°59′38″E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Autonomous region | Xinjiang |

| Prefecture | Kashgar |

| Area (2018)[1] | |

| • County-level city | 555 km2 (214 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 130 km2 (50 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,818 km2 (1,088 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,270 m (4,170 ft) |

| Population (2010 census) | |

| • County-level city | 506,640[2] |

| • Urban (2018)[3] | 1,020,000 |

| • Metro | 819,095 |

| • Metro density | 290/km2 (750/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | |

| • Major ethnic groups | Uyghur, Han Chinese |

| Time zones | UTC+08:00 (CST) |

| UTC+06:00 (Xinjiang Time (de facto)[4]) | |

| Postal code | 844000 |

| Area code(s) | 0998 |

| Website | www |

| Kashgar | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2.png) "Kashgar" in Uyghur Arabic (top) and Chinese characters (bottom) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | قەشقەر | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 喀什 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Kāshí | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 喀什噶尔 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 喀什噶爾 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | PRC Standard Mandarin: Kāshígá'ěr ROC Standard Mandarin: Kàshígé'ěr | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 疏勒 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Shūlè | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Third alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 疏附 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Shūfù | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

At the convergence point of widely varying cultures and empires, Kashgar has been under the rule of the Chinese, Turkic, Mongol and Tibetan empires. The city has also been the site of a number of battles between various groups of people on the steppes.

Now administered as a county-level unit, Kashgar is the administrative centre of Kashgar Prefecture, which has an area of 162,000 square kilometres (63,000 sq mi) and a population of approximately 4 million as of 2010.[10] The city itself has a population of 506,640, and its urban area covers 15 km2 (5.8 sq mi), though its administrative area extends over 555 km2 (214 sq mi). The city was made into a Special Economic Zone in 2010, the only city in western China with this distinction. Kashgar also forms a terminus of the Karakoram Highway, whose reconstruction is considered a major part of the multibillion-dollar China–Pakistan Economic Corridor.

Name

The modern Chinese name is 喀什 (Kāshí), a shortened form of the longer and less-frequently used 喀什噶尔 (Kāshígá'ěr; Uyghur: قەشقەر ). Ptolemy (AD 90-168), in his Geography, Chapter 15.3A, refers to Kashgar as “Kasi”.[11] Its western and probably indigenous name is the Kāš ("rock"), to which the East Iranian -γar ("mountain") and Middle Persian gar/ġar, from Old Persian/Pahlavi girīwa ("hill; ridge (of a mountain)") was attached. Alternative historical Romanizations for "Kashgar" include Cascar[12] and Cashgar.[13]

According to Subhash Kak, Kashgar appears to be the popular name from Sanskrit Kāśa+giri (काशगिरि: bright mountain).[14]

Non-native names for the city, such as the old Chinese name Shule 疏勒[15] and Tibetan Śu-lig[16] may have originated as an attempts to transcribe the Sanskrit name for Kashgar, Śrīkrīrāti ("fortunate hospitality").[17]

Variant transcriptions of the official Uyghur: يېڭىشەھەر [18] include: K̂äxk̂är or Kaxgar,[19] as well as Jangi-schahr,[20] Kashgar Yangi Shahr,[21] K’o-shih-ka-erh,[22] K’o-shih-ka-erh-hsin-ch’eng,[23] Ko-shih-ka-erh-hui-ch’eng,[24] K’o-shih-ko-erh-hsin-ch’eng,[25] New Kashgar,[26] Sheleh,[27] Shuleh,[28] Shulen,[29] Shu-lo,[30] Su-lo,[31] Su-lo-chen,[32] Su-lo-hsien,[33] Yangi-shaar,[34] Yangi-shahr,[35] Yangishar,[36] Yéngisheher,[37] Yengixəh̨ər[38] and Еңишәһәр.[39] - The postal romanization was 疏附 Shufu 1900s/50s, bilingual postmarks reading"SHUFU (KASHGAR)/date/疏附" were used in this period. 疏附 Shufu was also used on contemporary bilingual maps.

History

| Year | City Name | Dynasty | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≈ 2nd cent. BC |

Shule | Shule Kingdom | [Note 1] |

| ≈ 177 BC | Xiongnu | ||

| 60 BC | Western Han dynasty | [Note 2] | |

| 1st cent. AD |

Xiongnu, Yuezhi | ||

| 74 | Eastern Han dynasty | ||

| 107 | Northern Xiongnu | [40][41]:23 | |

| 127 | Eastern Han dynasty | [40][41]:23 | |

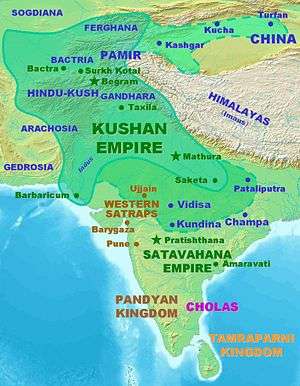

| 150 | Kushan | [41]:23 | |

| 323 | Kucha, Rouran | ||

| 384 | Former Qin | ||

| ≈450 | Hephthalite Empire | [41]:30 | |

| 492 | Gaoche | [40] | |

| ≈504 | Hephthalite Empire | [40] | |

| ≈552 | First Turkic Khaganate, | [40][41]:30 | |

| ≈583 | Western Turkic Khanate, | [40] | |

| 648 | Tang dynasty | [40] | |

| 651 | Western Turkic Khanate, | [40] | |

| 658 | Tang dynasty | [40] | |

| 670 | Tibetan Empire | [40] | |

| 679 | Tang dynasty | [40] | |

| 686 | Tibetan Empire | [40] | |

| 692 | Tang dynasty | [40] | |

| 790 | Tibetan Empire | [40] | |

| 791 | Uyghur Khanate | [40] | |

| 840 | Kashgar | Karakhanid Khanate | |

| 893 | |||

| 1041 | Eastern Karakhanid | ||

| 1134 | Karakhitai Khanate (Western Liao dynasty) |

||

| 1215 | |||

| 1218 | Mongol Empire | [40] | |

| 1266 | Chagatai Khanate | ||

| 1348 | Moghulistan (Eastern Chagatay) |

[40] | |

| 1387 | |||

| 1392 | Timurid dynasty | ||

| 1432 | Chagatay | ||

| 1466 | Dughlats | ||

| 1514 | Yarkent Khanate | [40] | |

| 1697 | Dzungar Khanate | ||

| 1759 | Qing dynasty | [40] | |

| 1865 | Emirate of Kashgaria | [40] | |

| 1877 | Qing dynasty | [40] | |

| 1913 | Republic of China | ||

| 1933 | East Turkestan Republic | ||

| 1934 | Republic of China | ||

| 1949- present |

Kashgar / Kashi | People's Republic of China | |

| Capital of an independent political entity | |||

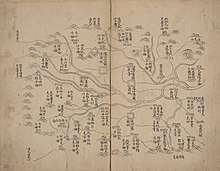

Han dynasty

The earliest mention of Kashgar occurs when a Chinese Han dynasty envoy traveled the Northern Silk Road to explore lands to the west.[42]

Another early mention of Kashgar is during the Former Han (also known as the Western Han dynasty), when in 76 BCE the Chinese conquered the Xiongnu, Yutian (Khotan), Sulei (Kashgar) and a group of states in the Tarim Basin almost up to the foot of the Tian Shan range.

Ptolemy speaks of Scythia beyond the Imaus, which is in a “Kasia Regio”, probably exhibiting the name from which Kashgar and Kashgaria (often applied to the district) are formed.[43] The country's people practised Zoroastrianism and Buddhism before the coming of Islam.

In the Book of Han, which covers the period between 125 BCE and 23 CE, it is recorded that there were 1,510 households, 18,647 people and 2,000 persons able to bear arms. By the time covered by the Book of the Later Han (roughly 25 to 170 CE), it had grown to 21,000 households and had 3,000 men able to bear arms.

The Book of the Later Han provides a wealth of detail on developments in the region:

In the period of Emperor Wu [140-87 BC], the Western Regions1 were under the control of the Interior [China]. They numbered thirty-six kingdoms. The Imperial Government established a Colonel [in charge of] Envoys there to direct and protect these countries. Emperor Xuan [73-49 BC] changed this title [in 59 BC] to Protector-General.

Emperor Yuan [40-33 BC] installed two Wuji Colonels to take charge of the agricultural garrisons on the frontiers of the king of Nearer Jushi [Turpan].

During the time of Emperor Ai [6 BCE - 1 CE] and Emperor Ping [1 - 5 CE], the principalities of the Western Regions split up and formed fifty-five kingdoms. Wang Mang, after he usurped the Throne [in 9 CE], demoted and changed their kings and marquises. Following this, the Western Regions became resentful and rebelled. They, therefore, broke off all relations with the Interior [China] and, all together, submitted to the Xiongnu again.

The Xiongnu collected oppressively heavy taxes and the kingdoms were not able to support their demands. In the middle of the Jianwu period [AD 25-56], they each [Shanshan and Yarkand in 38 and 18 kingdoms in 45], sent envoys to ask if they could submit to the Interior [China] and to express their desire for a Protector-General. Emperor Guangwu, decided that because the Empire was not yet settled [after a long period of civil war], he had no time for outside affairs and [therefore] finally refused his consent [in 45 CE].

In the meantime, the Xiongnu became weaker. The king of Suoju [Yarkand], named Xian, wiped out several kingdoms. After Xian’s death [c. 62 CE], they began to attack and fight each other. Xiao Yuan [Tura], Jingjue [Cadota], Ronglu [Niya] and Qiemo [Cherchen] were annexed by Shanshan [the Lop Nur region]. Qule [south of Keriya] and Pishan [modern Pishan or Guma] were conquered and fully occupied by Yutian [Khotan]. Yuli [Fukang], Danhuan, Guhu [Dawan Cheng] and Wutanzili were destroyed by Jushi [Turpan and Jimasa]. Later these kingdoms were re-established.

During the Yongping period [58 - 75 CE], the Northern Xiongnu forced several countries to help them plunder the commanderies and districts of Hexi. The gates of the towns stayed shut in broad daylight."[44]:3

More particularly, in reference to Kashgar itself, is the following record:

In the sixteenth Yongping year of Emperor Ming 73, Jian, the king of Qiuci (Kucha), attacked and killed Cheng, the king of Shule (Kashgar). Then he appointed the Qiuci (Kucha) Marquis of the Left, Douti, King of Shule (Kashgar). In winter 73 CE, the Han sent the Major Ban Chao who captured and bound Douti. He appointed Zhong, the son of the elder brother of Cheng, to be king of Shule (Kashgar). Zhong later rebelled. (Ban) Chao attacked and beheaded him.[44]:43

The Kushans

The Book of the Later Han also gives the only extant historical record of Yuezhi or Kushan involvement in the Kashgar oasis:

During the Yuanchu period (114-120) in the reign of Emperor, the king of Shule (Kashgar), exiled his maternal uncle Chenpan to the Yuezhi (Kushans) for some offence. The king of the Yuezhi became very fond of him. Later, Anguo died without leaving a son. His mother directed the government of the kingdom. She agreed with the people of the country to put Yifu (lit. “posthumous child”), who was the son of a full younger brother of Chenpan on the throne as king of Shule (Kashgar). Chenpan heard of this and appealed to the Yuezhi (Kushan) king, saying:

- "Anguo had no son. His relative (Yifu) is weak. If one wants to put on the throne a member of (Anguo’s) mother’s family, I am Yifu’s paternal uncle, it is I who should be king."

The Yuezhi (Kushans) then sent soldiers to escort him back to Shule (Kashgar). The people had previously respected and been fond of Chenpan. Besides, they dreaded the Yuezhi (Kushans). They immediately took the seal and ribbon from Yifu and went to Chenpan, and made him king. Yifu was given the title of Marquis of the town of Pangao [90 li, or 37 km, from Shule].

Then Suoju (Yarkand) continued to resist Yutian (Khotan), and put themselves under Shule (Kashgar). Thus Shule (Kashgar), became powerful and a rival to Qiuci (Kucha) and Yutian (Khotan)."[44]:43

However, it was not very long before the Chinese began to reassert their authority in the region:

In the second Yongjian year (127), during Emperor Shun’s reign, Chenpan sent an envoy to respectfully present offerings. The Emperor bestowed on Chenpan the title of Great Commandant-in-Chief for the Han. Chenxun, who was the son of his elder brother, was appointed Temporary Major of the Kingdom. In the fifth year (130), Chenpan sent his son to serve the Emperor and, along with envoys from Dayuan (Ferghana) and Suoju (Yarkand), brought tribute and offerings.[44]:43

From an earlier part of the same text comes the following addition:

In the first Yangjia year (132), Xu You sent the king of Shule (Kashgar), Chenpan, who with 20,000 men, attacked and defeated Yutian (Khotan). He beheaded several hundred people, and released his soldiers to plunder freely. He replaced the king [of Jumi] by installing Chengguo from the family of [the previous king] Xing, and then he returned.[44]:15

Then the first passage continues:

In the second Yangjia year (133), Chenpan again made offerings (including) a lion and zebu cattle.

Then, during Emperor Ling’s reign, in the first Jianning year [168], the king of Shule (Kashgar) and Commandant-in-Chief for the Han (i.e. presumably Chenpan), was killed while hunting by the youngest of his paternal uncles, Hede. Hede named himself king.

In the third year (170), Meng Tuo, the Inspector of Liangzhou, sent the Provincial Officer Ren She, commanding five hundred soldiers from Dunhuang, with the Wuji Major Cao Kuan, and Chief Clerk of the Western Regions, Zhang Yan, brought troops from Yanqi (Karashahr), Qiuci (Kucha), and the Nearer and Further States of Jushi (Turpan and Jimasa), altogether numbering more than 30,000, to punish Shule (Kashgar). They attacked the town of Zhenzhong [Arach − near Maralbashi] but, having stayed for more than forty days without being able to subdue it, they withdrew. Following this, the kings of Shule (Kashgar) killed one another repeatedly while the Imperial Government was unable to prevent it.[44]:43, 45

Three Kingdoms to the Sui dynasty

These centuries are marked by a general silence in sources on Kashgar and the Tarim Basin.

The Weilüe, composed in the second third of the 3rd century, mentions a number of states as dependencies of Kashgar: the kingdom of Zhenzhong (Arach?), the kingdom of Suoju (Yarkand), the kingdom of Jieshi, the kingdom of Qusha, the kingdom of Xiye (Khargalik), the kingdom of Yinai (Tashkurghan), the kingdom of Manli (modern Karasul), the kingdom of Yire (Mazar − also known as Tágh Nák and Tokanak), the kingdom of Yuling, the kingdom of Juandu (‘Tax Control’ − near modern Irkeshtam), the kingdom of Xiuxiu (‘Excellent Rest Stop’ − near Karakavak), and the kingdom of Qin.

However, much of the information on the Western Regions contained in the Weilüe seems to have ended roughly about (170), near the end of Han power. So, we cannot be sure that this is a reference to the state of affairs during the Cao Wei (220-265), or whether it refers to the situation before the civil war during the Later Han when China lost touch with most foreign countries and came to be divided into three separate kingdoms.

Chapter 30 of the Records of the Three Kingdoms says that after the beginning of the Wei Dynasty (220) the states of the Western Regions did not arrive as before, except for the larger ones such as Kucha, Khotan, Kangju, Wusun, Kashgar, Yuezhi, Shanshan and Turpan, who are said to have come to present tribute every year, as in Han times.

In 270, four states from the Western Regions were said to have presented tribute: Karashahr, Turpan, Shanshan, and Kucha. Some wooden documents from Niya seem to indicate that contacts were also maintained with Kashgar and Khotan around this time.

In 422, according to the Songshu, ch. 98, the king of Shanshan, Bilong, came to the court and "the thirty-six states in the Western Regions" all swore their allegiance and presented tribute. It must be assumed that these 36 states included Kashgar.

The "Songji" of the Zizhi Tongjian records that in the 5th month of 435, nine states: Kucha, Kashgar, Wusun, Yueban, Tashkurghan, Shanshan, Karashahr, Turpan and Sute all came to the Wei court.

In 439, according to the Weishu, ch. 4A, Shanshan, Kashgar and Karashahr sent envoys to present tribute.

According to the Weishu, ch. 102, Chapter on the Western Regions, the kingdoms of Kucha, Kashgar, Wusun, Yueban, Tashkurghan, Shanshan, Karashahr, Turpan and Sute all began sending envoys to present tribute in the Taiyuan reign period (435-440).

In 453 Kashgar sent envoys to present tribute (Weishu, ch. 5), and again in 455.

An embassy sent during the reign of Wencheng Di (452-466) from the king of Kashgar presented a supposed sacred relic of the Buddha; a dress which was incombustible.

In 507 Kashgar, is said to have sent envoys in both the 9th and 10th months (Weishu, ch. 8).

In 512, Kashgar sent envoys in the 1st and 5th months. (Weishu, ch. 8).

Early in the 6th century Kashgar is included among the many territories controlled by the Yeda or Hephthalite Huns, but their empire collapsed at the onslaught of the Western Turks between 563 and 567 who then probably gained control over Kashgar and most of the states in the Tarim Basin.

Tang dynasty

The founding of the Tang dynasty in 618 saw the beginning of a prolonged struggle between China and the Western Turks for control of the Tarim Basin. In 635, the Tang Annals reported an emissary from the king of Kashgar to the Tang capital. In 639 there was a second emissary bringing products of Kashgar as a token of submission to the Tang state.

Buddhist scholar Xuanzang passed through Kashgar (which he referred to as Ka-sha) in 644 on his return journey from India to China. The Buddhist religion, then beginning to decay in India, was active in Kashgar. Xuanzang recorded that they flattened their babies heads, tattooed their bodies and had green eyes. He reported that Kashgar had abundant crops, fruits and flowers, wove fine woolen stuffs and rugs. Their writing system had been adapted from Indian script but their language was different from that of other countries. The inhabitants were sincere Buddhist adherents and there were some hundreds of monasteries with more than 10,000 followers, all members of the Sarvastivadin School.

At around the same era, Nestorian Christians were establishing bishoprics at Herat, Merv and Samarkand, whence they subsequently proceeded to Kashgar, and finally to China proper itself.

In 646, the Turkic Kagan asked for the hand of a Tang Chinese princess, and in return the Emperor promised Kucha, Khotan, Kashgar, Karashahr and Sarikol as a marriage gift, but this did not happen as planned.

In a series of campaigns between 652 and 658, with the help of the Uyghurs, the Chinese finally defeated the Western Turk tribes and took control of all their domains, including the Tarim Basin kingdoms. Karakhoja was annexed in 640, Karashahr during campaigns in 644 and 648, and Kucha fell in 648.

In 662 a rebellion broke out in the Western Regions and a Chinese army sent to control it was defeated by the Tibetans south of Kashgar.

After another defeat of the Tang Chinese forces in 670, the Tibetans gained control of the whole region and completely subjugated Kashgar in 676-8 and retained possession of it until 692, when the Tang dynasty regained control of all their former territories, and retained it for the next fifty years.

In 722 Kashgar sent 4,000 troops to assist the Chinese to force the "Tibetans out of "Little Bolu" or Gilgit.

In 728, the king of Kashgar was awarded a brevet by the Chinese emperor.

In 739, the Tangshu relates that the governor of the Chinese garrison in Kashgar, with the help of Ferghana, was interfering in the affairs of the Turgesh tribes as far as Talas.

In 751 the Chinese were defeated by an Arab army in the Battle of Talas. The An Lushan Rebellion led to the decline of Tang influence in Central Asia due to the fact that the Tang dynasty was forced to withdraw its troops from the region to fight An Lushan. The Tibetans cut all communication between China and the West in 766.

Soon after the Chinese pilgrim monk Wukong passed through Kashgar in 753. He again reached Kashgar on his return trip from India in 786 and mentions a Chinese deputy governor as well as the local king.

Battles with Arab Caliphate

| Part of a series on Islam in China | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

|

||||||

|

| ||||||

In 711, the Arabs invaded Kashgar.[45] It is alleged that Qutayba ibn Muslim in 712-715 had conquered Xinjiang.[46][47] Although the Muslim religion from the very commencement sustained checks, it nevertheless made its weight felt upon the independent states of Turkestan to the north and east, and thus acquired a steadily growing influence. It was not, however, till the 10th century that Islam was established at Kashgar,[48] under the Kara-Khanid Khanate.

The fall of Kashgar to Qutayba ibn Muslim is claimed as the start of Islam in the region by Al-Qaeda ideologue Mustafa Setmariam Nasar[49] and by an article from Al-Qaeda branch Al-Nusra Front's English language "Al-Risalah magazine" (مجلة الرسالة), second issue (العدد الثاني), translated from English into Turkish by the "Doğu Türkistan Haber Ajansı" (East Turkestan News Agency) and titled Al Risale: "Türkistan Dağları" 1. Bölüm (The Message : "Turkistan Mountains" Part 2.)[50][51]

The Turkic Rule

According to the 10th-century text, Hudud al-'alam, "the chiefs of Kashghar in the days of old were from the Qarluq, or from the Yaghma."[52] The Karluks, Yaghmas and other tribes such as the Chigils formed the Karakhanids. The Karakhanid Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan converted to Islam in the 10th century and captured Kashgar. Kashgar was the capital of the Karakhanid state for a time but later the capital was moved to Balasaghun. During the latter part of the 10th century, the Muslim Karakhanids began a struggle against the Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan, and the Khotanese defeated the Karakhanids and captured Kashgar in 970.[53] Chinese sources recorded the king of Khotan offering to send them a dancing elephant captured from Kashgar.[54] Later in 1006, the Karakhanids of Kashgar under Yusuf Kadr Khan conquered Khotan.

The Karakhanid Khanate however was beset with internal strife, and the khanate split into two, the Eastern and Western Karakhanid Khanates, with Kashgar falling within the domain of the Eastern Karakhanid state.[55] In 1089, the Western Karakhanids fell under the control of the Seljuks, but the Eastern Karakhanids was for the most part independent.

Both the Karakhanid states were defeated in the 12th century by the Kara-Khitans who captured Balasaghun, however Karakhanid rule continued in Kashgar under the suzerainty of the Kara-Khitans.[56] The Kara-Khitan rulers followed a policy of religious tolerance, Islamic religious life continued uninterrupted and Kashgar was also a Nestorian metropolitan see.[57] The last Karakhanid of Kashgar was killed in a revolt in 1211 by the city's notables. Kuchlug, a usurper of the throne of the Kara-Khitans, then attacked Kashgar which finally surrendered in 1214.[58]

The Mongols

The Kara-Khitai in their turn were swept away in 1219 by Genghis Khan. After his death, Kashgar came under the rule of the Chagatai Khans. Marco Polo visited the city, which he calls Cascar, about 1273-4 and recorded the presence of numerous Nestorian Christians, who had their own churches. Later In the 14th century, a Chagataid khan Tughluq Timur converted to Islam, and Islamic tradition began to reassert its ascendancy.

In 1389−1390 Tamerlane ravaged Kashgar, Andijan and the intervening country. Kashgar endured a troubled time, and in 1514, on the invasion of the Khan Sultan Said, was destroyed by Mirza Ababakar, who with the aid of ten thousand men built a new fort with massive defences higher up on the banks of the Tuman river. The dynasty of the Chagatai Khans collapsed in 1572 with the division of the country among rival factions; soon after, two powerful Khoja factions, the White and Black Mountaineers (Ak Taghliq or Afaqi, and Kara Taghliq or Ishaqi), arose whose differences and war-making gestures, with the intermittent episode of the Oirats of Dzungaria, make up much of recorded history in Kashgar until 1759. The Dzungar Khanate conquered Kashgar and set up the Khoja as their puppet rulers.

Qing conquest

The Qing dynasty defeated the Dzungar Khanate during the Ten Great Campaigns and took control of Kashgar in 1759. The conquerors consolidated their authority by settling other ethnics emigrants in the vicinity of a Manchu garrison.

Rumours flew around Central Asia that the Qing planned to launch expeditions towards Transoxiana and Samarkand, the chiefs of which sought assistance from the Afghan king Ahmed Shah Abdali. The alleged expedition never happened so Ahmad Shah withdrew his forces from Kokand. He also dispatched an ambassador to Beijing to discuss the situation of the Afaqi Khojas, but the representative was not well received, and Ahmed Shah was too busy fighting off the Sikhs to attempt to enforce his demands through arms.

The Qing continued to hold Kashgar with occasional interruptions during the Afaqi Khoja revolts. One of the most serious of these occurred in 1827, when the city was taken by Jahanghir Khoja; Chang-lung, however, the Qing general of Ili, regained possession of Kashgar and the other rebellious cities in 1828.

The Kokand Khanate raided Kashgar several times. A revolt in 1829 under Mahommed Ali Khan and Yusuf, brother of Jahanghir resulted in the concession of several important trade privileges to the Muslims of the district of Altishahr (the "six cities"), as it was then called.

The area enjoyed relative calm until 1846 under the rule of Zahir-ud-din, the local Uyghur governor, but in that year a new Khoja revolt under Kath Tora led to his accession as the authoritarian ruler of the city. However, his reign was brief—at the end of seventy-five days, on the approach of the Chinese, he fled back to Khokand amid the jeers of the inhabitants. The last of the Khoja revolts (1857) was of about equal duration, and took place under Wali-Khan, who murdered the well-known traveler Adolf Schlagintweit.

1862 Chinese Hui revolt

The great Dungan revolt (1862–1877) involved insurrection among various Muslim ethnic groups. It broke out in 1862 in Gansu then spread rapidly to Dzungaria and through the line of towns in the Tarim Basin.

Dungan troops based in Yarkand rose and in August 1864 massacred some seven thousand Chinese and their Manchu commander. The inhabitants of Kashgar, rising in their turn against their masters, invoked the aid of Sadik Beg, a Kyrgyz chief, who was reinforced by Buzurg Khan, the heir of Jahanghir Khoja, and his general Yakub Beg. The latter men were dispatched at Sadik's request by the ruler of Khokand to raise what troops they could to aid his Muslim friends in Kashgar.

Sadik Beg soon repented of having asked for a Khoja, and eventually marched against Kashgar, which by this time had succumbed to Buzurg Khan and Yakub Beg, but was defeated and driven back to Khokand. Buzurg Khan delivered himself up to indolence and debauchery, but Yakub Beg, with singular energy and perseverance, made himself master of Yangi Shahr, Yangi-Hissar, Yarkand and other towns, and eventually became sole master of the country, Buzurg Khan proving himself totally unfit for the post of ruler.

With the overthrow of Chinese rule in 1865 by Yakub Beg (1820–1877), the manufacturing industries of Kashgar are supposed to have declined.

Yaqub Beg entered into relations and signed treaties with the Russian Empire and the British Empire, but when he tried to get their support against China, he failed.

Kashgar and the other cities of the Tarim Basin remained under Yakub Beg's rule until May 1877, when he died at Korla. Thereafter Kashgaria was reconquered by the forces of the Qing general Zuo Zongtang during the Qing reconquest of Xinjiang.

Qing rule

There were eras in Xinjiang's history where intermarriage was common, and "laxity" set upon Uyghur women led them to marry Chinese men in the period after Yakub Beg's rule ended. It is also believed by Uyghurs that some Uyghurs have Han Chinese ancestry from historical intermarriage, such as those living in Turpan.[59]

Even though Muslim women are forbidden to marry non-Muslims in Islamic law, from 1880 to 1949 it was frequently violated in Xinjiang when Chinese men married Uyghur women. Because they were viewed as "outcast", Islamic cemeteries banned the Uyghur wives of Chinese men from being buried within them. Uyghur women got around this problem by giving shrines donations and buying a grave in other towns. Besides Chinese men, other men such as Hindus, Armenians, Jews, Russians, and Badakhshanis (Pamiris) intermarried with local Uyghur women.[60]:84 The local society accepted the Uyghur women and Chinese men's mixed offspring as their own people despite the marriages being in violation of Islamic law.

An anti-Russian uproar broke out when Russian customs officials, 3 Cossacks and a Russian courier invited local Uyghur prostitutes to a party in January 1902 in Kashgar. There was a general anti-Russian sentiment, but the inflamed local Uyghur populace started a brawl with the Russians on the pretense of protecting their women. Even though morality was not strict in Kashgar, the local population confronted with the Russians before they were dispersed by guards, and the Chinese then sought to end tensions by preventing the Russians from building up a pretext to invade.[61]:124

After the riot, the Russians sent troops to Sarikol in Tashkurghan and demanded that the Sarikol postal services be placed under Russian supervision, the locals of Sarikol believed that the Russians would seize the entire district from the Chinese and send more soldiers even after the Russians tried to negotiate with the Begs of Sarikol and sway them to their side, they failed since the Sarikoli officials and authorities demanded in a petition to the Amban of Yarkand that they be evacuated to Yarkand to avoid being harassed by the Russians and objected to the Russian presence in Sarikol, the Sarikolis did not believe the Russian claim that they would leave them alone and only involved themselves in the mail service.[61]:125

Republic of China (1913-1933)

First East Turkestan Republic

Kashgar was the scene of continual battles from 1933 to 1934. Ma Shaowu, a Chinese Muslim, was the Tao-yin of Kashgar, and he fought against Uyghur rebels. He was joined by another Chinese Muslim general, Ma Zhancang.

Battle of Kashgar (1933)

Uighur and Kirghiz forces, led by the Bughra brothers and Tawfiq Bay, attempted to take the New City of Kashgar from Chinese Muslim troops under General Ma Zhancang. They were defeated.

Tawfiq Bey, a Syrian Arab traveler, who held the title Sayyid (descendant of Muhammed) and arrived at Kashgar on August 26, 1933, was shot in the stomach by the Chinese Muslim troops in September. Previously Ma Zhancang arranged to have the Uighur leader Timur Beg killed and beheaded on August 9, 1933, displaying his head outside of Id Kah Mosque.

Han Chinese troops commanded by Brigadier Yang were absorbed into Ma Zhancang's army. A number of Han Chinese officers were spotted wearing the green uniforms of Ma Zhancang's unit of the 36th division; presumably they had converted to Islam.[62]

Battle of Kashgar (1934)

The 36th division General Ma Fuyuan led a Chinese Muslim army to storm Kashgar on February 6, 1934, attacking the Uighur and Kirghiz rebels of the First East Turkestan Republic. He freed another 36th division general, Ma Zhancang, who was trapped with his Chinese Muslim and Han Chinese troops in Kashgar New City by the Uighurs and Kirghiz since May 22, 1933. In January, 1934, Ma Zhancang's Chinese Muslim troops repulsed six Uighur attacks, launched by Khoja Niyaz, who arrived at the city on January 13, 1934, inflicting massive casualties on the Uighur forces.[63] From 2,000 to 8,000 Uighur civilians in Kashgar Old City were massacred by Tungans in February, 1934, in revenge for the Kizil massacre, after retreating of Uighur forces from the city to Yengi Hisar. The Chinese Muslim and 36th division Chief General Ma Zhongying, who arrived at Kashgar on April 7, 1934, gave a speech at Id Kah Mosque in April, reminding the Uighurs to be loyal to the Republic of China government at Nanjing. Several British citizens at the British consulate were killed or wounded by the 36th division on March 16, 1934.[64][65][66][67]

Republic of China (1934-1949)

People's Republic of China

Kashgar was incorporated into the People's Republic of China in 1949. During the Cultural Revolution, one of the largest statues of Mao in China was built in Kashgar, near People's Square.

On October 31, 1981, an incident occurred in the city due to a dispute between Uyghurs and Han Chinese in which three were killed. The incident was quelled by an army unit.[68][69]

In 1986, the Chinese government designated Kashgar a "city of historical and cultural significance". Kashgar and surrounding regions have been the site of Uyghur unrest since the 1990s. In 2008, two Uyghur men carried out a vehicular, IED and knife attack against police officers. In 2009, development of Kashgar's old town accelerated after the revelations of the deadly role of faulty architecture during the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. Many of the old houses in the old town were built without regulation, and as a result, officials found them to be overcrowded and non-compliant with fire and earthquake codes. Additionally, the newer buildings may also have been built with increased ease of surveillance in mind.[70]

When the plan started, 42% of the city's residents lived in the old town. As the plan was undertaken, residents have been removed from their homes in order to demolish large sections of the old city and replace these areas with new developments.[71] The European Parliament issued a resolution in 2011 calling for "culture-sensitive methods of renovation."[72] The International Scientific Committee on Earthen Architectural Heritage (ISCEAH) has expressed concern over the demolition and reconstruction of historic buildings. ISCEAH has, additionally, urged the implementation of techniques utilized elsewhere in the world to address earthquake vulnerability.[73]

Following the July 2009 Ürümqi riots, the government focused on local economic development in an attempt to ameliorate ethnic tensions in the greater Xinjiang region. Kashgar was made into a Special Economic Zone in 2010, the first such zone in China's far west. In 2011, a spate of violence over two days killed dozens of people. By May 2012, two-thirds of the old city had been demolished, fulfilling "political as well as economic goals."[74] Critics have called the destruction of the old city part of a campaign of cultural genocide.[75] In July 2014, the Imam of the Id Kah Mosque, Juma Tayir, was assassinated in Kashgar.

On October 21, 2014, Aqqash Township (Akekashi) was transferred from Konaxahar (Shufu) County to Kashgar city.[76]

Climate

Kashgar features a desert climate (Köppen BWk) with hot summers and cold winters, with large temperature differences between those two seasons: The monthly 24-hour average temperature ranges from −4.8 °C (23.4 °F) in January to 25.6 °C (78.1 °F) in July, while the annual mean is 12.28 °C (54.1 °F). Spring is long and arrives quickly, while fall is somewhat brief in comparison. Kashgar is one of the driest cities on the planet, averaging only 71.4 mm (2.81 in) of precipitation per year. The city's wettest month, May, only sees on average 11.2 mm (0.44 in) of rain. Because of the extremely arid conditions, snowfall is rare, despite the cold winters. Records have been as low as −24.4 °C (−12 °F) in January and up to 40.1 °C (104.2 °F) in July. The frost-free period averages 215 days. With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 50% in March to 70% in September, the city receives 2,726 hours of bright sunshine annually.

| Climate data for Kashgar (1981−2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

6.1 (43.0) |

14.5 (58.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

26.7 (80.1) |

30.3 (86.5) |

32.0 (89.6) |

30.9 (87.6) |

26.6 (79.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

11.2 (52.2) |

2.3 (36.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.8 (23.4) |

0.4 (32.7) |

8.5 (47.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −9.6 (14.7) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

2.6 (36.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.8 (62.2) |

18.8 (65.8) |

17.6 (63.7) |

12.5 (54.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 2.7 (0.11) |

3.7 (0.15) |

7.2 (0.28) |

5.1 (0.20) |

11.2 (0.44) |

9.1 (0.36) |

9.2 (0.36) |

7.7 (0.30) |

6.3 (0.25) |

5.5 (0.22) |

2.1 (0.08) |

1.6 (0.06) |

71.4 (2.81) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 27.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66 | 56 | 45 | 38 | 40 | 40 | 43 | 48 | 53 | 56 | 60 | 69 | 51 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 154.9 | 160.1 | 184.5 | 213.7 | 255.6 | 304.3 | 312.2 | 287.5 | 259.4 | 239.9 | 196.2 | 158.0 | 2,726.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 52 | 53 | 50 | 54 | 58 | 68 | 69 | 68 | 70 | 69 | 65 | 54 | 61.5 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration (precipitation days and sunshine 1971–2000)[77][78] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

Kashgar includes eight subdistricts, two towns, and nine townships.[79][80][81]

Subdistricts (كوچا باشقارمىسى / 街道)

- Chasa Subdistrict (Qiasa; چاسا كوچا باشقارمىسى / 恰萨街道), Yawagh Subdistrict (Yawage; ياۋاغ كوچا باشقارمىسى / 亚瓦格街道), Östeng Boyi Subdistrict (Wusitangboyi; ئۆستەڭ بويى كوچا باشقارمىسى / 吾斯塘博依街道), Qum Derwaza Subdistrict (Kumudai'erwazha; قۇم دەرۋازا كوچا باشقارمىسى / 库木代尔瓦扎街道), Gherbiz Yurt Avenue Subdistrict (Xiyu Dadao; غەربىي يۇرت يولى كوچا باشقارمىسى / 西域大道街道), Sherqiy Köl Subdistrict (Donghu; شەرقىي كۆل كوچا باشقارمىسى / 东湖街道), Merhaba Avenue Subdistrict (Yingbin Dadao; مەرھابا يولى كوچا باشقارمىسى / 迎宾大道街道), Gherbiz Baghcha Subdistrict (Xigongyuan; غەربىي باغچا كوچا باشقارمىسى / 西公园街道)

Towns (بازىرى / 镇)

- Nezerbagh[82][83][84] (Naize'er Bage;[85] نەزەرباغ بازىرى[86] / 乃则尔巴格镇; formerly 乃则尔巴格乡), Shamalbagh (Xiamalebage; شامالباغ بازىرى[87] / 夏马勒巴格镇; formerly 夏马勒巴格乡)

Townships (يېزىسى / 乡)

- Döletbagh Township (Duolaitebage; دۆلەتباغ يېزىسى / 多来特巴格乡), Qoghan Township (Haohan; قوغان يېزىسى / 浩罕乡), Semen Township (Seman; سەمەن يېزىسى[88] / 色满乡), Xangdi Township (Huangdi; خاڭدى يېزىسى / 荒地乡), Beshkërem Township (Baishikeranmu; بەشكېرەم يېزىسى / 伯什克然木乡), Paxtekle Township (Pahataikeli; پاختەكلە يېزىسى / 帕哈太克里乡), Awat Township (Awati; ئاۋات يېزىسى / 阿瓦提乡), Yëngi’östeng Township (Yingwusitan; يېڭىئۆستەڭ يېزىسى / 英吾斯坦乡 / 英吾斯塘乡[89]), Aqqash Township (Akekashi; ئاققاش يېزىسى / 阿克喀什乡)

Demographics

Kashgar is predominantly populated by Muslim Uyghurs. Compared to Ürümqi, Xinjiang's capital and largest city, Kashgar is less industrial and has significantly fewer Han Chinese residents. In 1998, the urban population of Kashgar was recorded as 311,141, with 81% Uyghurs and 18% Han Chinese.[90]

In the 2000 census, the population of the city of Kashgar was given as 340,640. In the 2010 census, this number increased to 506,640. Some of the increase is due to boundary changes and the number may include some rural population.[91]

As of 2015, 534,848 of the 628,302 residents of the county were Uyghur, 88,583 were Han Chinese and 4,871 were from other ethnic groups.[92]

As of 1999, 81.24% of the population of Kashgar (Kashi) city was Uyghur and 17.87% of the population was Han Chinese.[93]

Kasghar Census 2015[92]

| Ethnicity | Inhabitants | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Uyghur | 4,140,255 | 92.02% |

| Han Chinese | 292.972 | 6.51% |

| Tajik | 42,746 | 0.95% |

| Kyrgyz | 7,036 | 0.15% |

| Hui | 6,395 | 0.14% |

| Uzbek | 4,767 | 0.10% |

| Korean | 1,658 | 0.03% |

| Mongol | 740 | 0.01% |

| Manchu | 603 | 0.01% |

| Others | 1,980 | 0.04% |

Economy

The city has a very important Sunday market. Thousands of farmers from the surrounding fertile lands come into the city to sell a wide variety of fruit and vegetables. Kashgar's livestock market is also very lively. Silk and carpets made in Hotan are sold at bazaars, as well as local crafts, such as copper teapots and wooden jewellery boxes.

In order to boost the economy in Kashgar region, the government classified the area as the sixth Special Economic Zone of China in May 2010.[94]

The movie The Kite Runner was filmed in Kashgar. Kashgar and the surrounding countryside stood in for Kabul and Afghanistan, since filming in Afghanistan was not possible due to safety and security reasons.

Sights

Before its demolition, Kashgar's Old City had been called "the best-preserved example of a traditional Islamic city to be found anywhere in Central Asia".[95] There is a new "Old Kashgar" but it is a dystopia.[96] It is estimated to attract more than one million tourists annually.[97]

- Id Kah Mosque, the largest mosque in China, is located in the heart of the city.

- People's Park, the main public park in central Kashgar.

- An 18 m (59 ft) high statue of Mao Zedong in Kashgar is one of the few large-scale statues of Mao remaining in China.

- The tomb of Afaq Khoja in Kashgar is considered the holiest Muslim site in Xinjiang. Built in the 17th century, the tiled mausoleum 5 km (3.1 mi) northeast of the city centre also contains the tombs of five generations of his family. Abakh was a powerful ruler, controlling Khotan, Yarkand, Korla, Kucha and Aksu as well as Kashgar. Among some Uyghur Muslims, he was considered a great Saint (Aulia).

- Sunday Market in Kashgar is renowned as the biggest market in central Asia; a pivotal trading point along the Silk Road where goods have been traded for more than 2,000 years. The market is open every day but Sunday is the largest.[98]

.jpg)

- Kashgar minaret at night

The tomb of Afaq Khoja

The tomb of Afaq Khoja Mosque next to the tomb of Afaq Khoja.

Mosque next to the tomb of Afaq Khoja. Mao statue in the city square of Kashgar.

Mao statue in the city square of Kashgar.

Transportation

Air

Kashgar Airport serves mainly domestic flights, the majority of them from Urumqi.

Rail

Kashgar has the westernmost railway station in China.[99] It is connected to the rest of China's rail network via the Southern Xinjiang Railway, which was built in December 1999. Kashgar–Hotan Railway opened for passenger traffic in June 2011, and connected Kashgar with cities in the southern Tarim Basin including Shache (Yarkand), Yecheng (Kargilik) and Hotan. Travel time to Urumqi from Kashgar is approximately 25 hours, while travel time to Hotan is approximately ten hours.

The investigation work of a further extension of the railway line to Pakistan has begun. In November 2009, Pakistan and China agreed to set up a joint venture to do a feasibility study of the proposed rail link via the Khunjerab Pass.[100]

Proposals for a rail connection to Osh in Kyrgyzstan have also been discussed at various levels since at least 1996.[101]

In 2012, a standard gauge railway from Kashgar via Tajikistan and Afghanistan to Iran and beyond has been proposed.[102]

Road

The Karakorum highway (KKH) links Islamabad, Pakistan with Kashgar over the Khunjerab Pass. The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor is a multibillion-dollar project was that will upgrade transport links between China and Pakistan, including the upgrades to the Karakorum highway. Bus routes exist for passenger travel south into Pakistan. Kyrgyzstan is also accessible from Kashgar, via the Torugart Pass or the Irkeshtam Pass; as of summer 2007, daily bus service connects Kashgar with Bishkek's Western Bus Terminal.[103] Kashgar is also located on China National Highways G314 (which runs to Khunjerab Pass on the Sino−Pakistani border, and, in the opposite direction, towards Ürümqi), and G315, which runs to Xining, Qinghai from Kashgar.

International relations

Consulates (in the past)

The British Empire had a consulate from 1890 to 1948 at Kashgar. Though a British consulate, it was manned and paid by the Indian Political Department of British India. The consulate was not fully recognized by Qing China until 1908. It was upgraded to a consulate-general in 1911.[104]

The wives of the inaugural consul and of the last consul left important ethnographic accounts of Kashgar, namely An English Lady in Chinese Turkestan (1931) by Lady Macartney and That Antique Land (1950) by Diana Shipton, the wive of mountaineer and consul Eric Shipton.

Twin towns – Sister cities

Kashgar is twinned with:

Notable persons

- Abdurehim Heyt, Uyghur folk singer

- Nury Turkel, commissioner on the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom

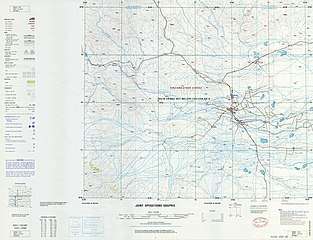

Notes

- From map: "DELINEATION OF INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES MUST NOT BE CONSIDERED AUTHORITATIVE"

- Capital of the Shule Kingdom.

- During the Eastern Han dynasty, Shule was administered by the Protectorate of the Western Regions.

References

Citations

- Cox, W (2018). Demographia World Urban Areas. 14th Annual Edition (PDF). St. Louis: Demographia. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-05-03. Retrieved 2018-06-15.

- "China - Xinjiang Weiwu'er Zizhiqu". GeoHive. Archived from the original on 2013-05-12.

- Cox, W (2018). Demographia World Urban Areas. 14th Annual Edition (PDF). St. Louis: Demographia. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-05-03. Retrieved 2018-06-15.

- "The Working-Calendar for The Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Government". Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Government. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007.

- "Xinjiang's Kashgar to provide duty-free shopping". Embassy of the People's Republic of China in the United States of America. 10 December 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

Kashgar will start providing duty-free shopping from 2015 as the Xinjiang city tries to build itself as a trade hub in Central Asia.

- mingmei, ed. (18 May 2020). "Non-stop flight to link Beijing, Xinjiang's Kashgar". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

A new direct air route linking Beijing and the city of Kashgar, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, will be launched on June 10, according to Air China.

- Collins World Atlas Illustrated Edition (3rd ed.). HarperCollins. 2007. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-00-723168-3 – via Internet Archive.

Kashi (Kashgar)

- 中国地名录. Beijing: SinoMaps Press. 1997. ISBN 7-5031-1718-4.

- World Atlas Trade & Logistics Edition. World Trade Press. 2008. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-885073-44-0 – via Internet Archive.

Kashi

- Stanley W. Toops (August 2012). Susan M. Walcott; Corey Johnson (eds.). Eurasian Corridors of Interconnection: From the South China to the Caspian Sea. Routledge. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-1135078751.

- de la Vaissière, Étienne (2009). "The Triple System of Orography in Ptolemy's Xinjiang". In Sundermann, Werner; Hintze, Almut; de Blois, François (eds.). Exegisti monumenta : Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. 530. ISBN 978-3-447-05937-4.

- E.g., René Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, ISBN 0-8135-1304-9, p. 360; "Cascar" is the spelling used in most accounts of the travels of Bento de Góis, starting with the main primary source: Trigault, Nicolas S. J. "China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Mathew Ricci: 1583–1610". English translation by Louis J. Gallagher, S.J. (New York: Random House, Inc. 1953). Cascar (Kashgar) is discussed extensively in, Book Five, Chapter 11, "Cathay and China: The Extraordinary Odyssey of a Jesuit Lay Brother" and Chapter 12, "Cathay and China Proved to Be Identical."(pp. 499–521 in 1953 edition). The full Latin text Archived 2016-04-30 at the Wayback Machine of the original work, De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas, is available on Google Books.

- Gützlaff, Karl Friedrich A. (1852). George Thomas Staunton (ed.). The life of Taou-kwang, late emperor of China: with memoirs of the court of Peking.

- https://medium.com/@subhashkak1/the-r%C4%81ma-story-and-sanskrit-in-ancient-xinjiang-4ce8636285ae

- "Shule: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- P. Lurje: KASHGAR Archived 2013-05-17 at the Wayback Machine. In Encyclopaedia Iranica, 2009, Vol. XVI, Fasc. 1, p. 48-50.

- John E. Hill, 2011, "Section 21 – The Kingdom of Shule 疏勒 (Kashgar)" Archived 2016-04-04 at the Wayback Machine, A Translation of the Chronicle on the ‘Western Regions’ from the Hou Hanshu. Based on a report by General Ban Yong to Emperor An (107-125 CE) near the end of his reign, with a few later additions. Compiled by Fan Ye (398-446 CE). (Access: 16 May 2016.)

- "يېڭىشەھەر: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- 国家测绘局地名研究所 (1997). 中国地名录 [Gazetteer of China]. Beijing: SinoMaps Press. p. 117. ISBN 7-5031-1718-4.

- "Jangi-schahr: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Kashgar Yangi Shahr: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "K'o-shih-ka-erh: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "K'o-shih-ka-erh-hsin-ch'eng: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Ko-shih-ka-erh-hui-ch'eng: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "K'o-shih-ko-erh-hsin-ch'eng: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "New Kashgar: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Sheleh: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Shuleh: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Shulen: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Shu-lo: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Su-lo: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Su-lo-chen: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Su-lo-hsien: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Yangi-shaar: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Yangi-shahr: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Yangishar: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Yéngisheher: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Yengixəh̨ər: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "Еңишәһәр: China". Geographical Names. Archived from the original on 2011-08-18. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- 《疏勒县志》"第二节 历史沿革" (in Chinese). Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- James Millward (2007), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang

- "Silk Road, North China, C. Michael Hogan, the Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham". Archived from the original on 2017-06-28. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- "The Triple System of Orography in Ptolemy's Xinjiang", pp. 530–531. Étienne de la Vaissière.(2009) Exegisti monumenta: Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams. Eds W. Sundermann, A. Hintze and F. de Blois Harrassowitz Verlag Wiesbaden. ISBN 978-3-447-05937-4

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger, eds. (2012). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 598. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6.

- Michael Dillon (1 August 2014). Xinjiang and the Expansion of Chinese Communist Power: Kashgar in the Early Twentieth Century. Routledge. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-1-317-64721-8.

- Marshall Broomhall (1910). Islam in China: A Neglected Problem. Morgan & Scott, Limited. pp. 17–.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-11-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Mustafa Setmariam Nasar (aliases Abu Musab al-Suri and Umar Abd al-Hakim) (1999). "Muslims in Central Asia and The Coming Battle of Islam". Archived from the original on 2016-01-19.

-

- "Al Risale : "Türkistan Dağları " 2. Bölüm". Doğu Türkistan Bülteni Haber Ajansı. Translated by Bahar Yeşil. 29 October 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- "El Risale Dergisi'nden Türkistan Dağları -2. Bölüm-". ISLAH HABER "Özgür Ümmetin Habercisi". Translated by Bahar Yeşil. 30 October 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016.

- Zelin, Aaron Y. (October 25, 2015). "New issue of the magazine: "al-Risālah #2"". JIHADOLOGY: A clearinghouse for jihādī primary source material, original analysis, and translation service. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017.

- Scott Cameron Levi, Ron Sela (2010). "Chapter 4, Discourse on the Country of the Yaghma and its Towns". Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- Valerie Hansen (11 October 2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-0-19-515931-8.

- E. Yarshater (ed.). "Chapter 7, The Iranian Settlements to the East of the Pamirs". The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

- Davidovich, E. A. (1998), "Chapter 6 The Karakhanids", in Asimov, M.S.; Bosworth, C.E. (eds.), History of Civilisations of Central Asia, 4 part I, UNESCO Publishing, pp. 119–144, ISBN 92-3-103467-7

- Golden, Peter. B. (1990), "The Karakhanids and Early Islam", in Sinor, Denis (ed.), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 357, ISBN 0-521-24304-1

- Sinor, D. (1998), "Chapter 11 - The Kitan and the Kara Kitay", in Asimov, M.S.; Bosworth, C.E. (eds.), History of Civilisations of Central Asia, 4 part I, UNESCO Publishing, ISBN 92-3-103467-7

- Biran, Michal. (2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 0-521-84226-3.

- Joanne N. Smith Finley (9 September 2013). The Art of Symbolic Resistance: Uyghur Identities and Uyghur-Han Relations in Contemporary Xinjiang. BRILL. pp. 309–. ISBN 978-90-04-25678-1.

- Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880-1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2.

- Pamela Nightingale; C.P. Skrine (5 November 2013) [First published 1973]. Macartney at Kashgar: New Light on British, Chinese and Russian Activities in Sinkiang, 1890-1918. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-57609-6.

- Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 288. ISBN 0-521-25514-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- AP (1 February 1934). "REPULSE REBELS AFTER SIX DAYS". Spokane Daily Chronicle.

- AP (17 March 1934). "TUNGAN RAIDERS MASSACRE 2,000". The Miami News.

- Associated Press Cable (17 March 1934). "TUNGANS SACK KASHGAR CITY, SLAYING 2,000". The Montreal Gazette.

- The Associated Press (17 March 1934). "British Officials and 2,000 Natives Slain At Kashgar, on Western Border of China". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- AP (17 March 1934). "2000 Killed In Massacre". San Jose News.

- Tiziano Terzani (1985). The Forbidden Door. Asia 2000 Ltd. p. 224 – via Internet Archive.

A similar incident occurred in the center of Kashgar on October 31, 1981. A group of Uighur workers wanted to dig a trench in the pavement in front of a state shop run by Hans. The initial discussion became a quarrel and a Han ended up shooting and killing one of the Uighurs with a shotgun. Thousands of Uighurs joined in. For hours the city was in chaos, and two Hans were killed. An Army unit had to be called in to quell the violence and separate the two communities.

- "33. China/Uighurs (1949-present)". University of Central Arkansas. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

Two individuals were killed in ethnic violence in Kashgar on October 30, 1981.

- Buckley, Chris; Mozur, Paul; Ramzy, Austin (2019-04-04). "How China Turned a City Into a Prison". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2019-04-04. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- Fan, Maureen (March 24, 2009). "An Ancient Culture, Bulldozed Away". Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- "JOINT MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION". European Parliament. 9 March 2011. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ICOMOS-ISCEAH (2009). "Heritage in the Aftermath of the Sichuan Earthquake". In Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer (Eds.), "Heritage at Risk: ICOMOS World Report 2008–2010 on Monuments and Sites in Danger" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-06-23. Retrieved 2011-06-06. Berlin: hendrik Bäßler verlag, 2010.

- Nick Holdstock, "Razing Kashgar Archived 2012-05-29 at the Wayback Machine," LRB blog, London Review of Books, 25 May 2012.

- Lipes, Joshua (June 5, 2020). "Kashgar's Old City Destruction Emblematic of Beijing's Cultural Campaign Against Uyghurs: Report". Radio Free Asia. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- "Archived copy" 疏附县历史沿革. XZQH.org. 14 November 2014. Archived from the original on 8 November 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

2014年,自治区政府(新政函[2014]8号)同意撤销乌帕尔乡,设立乌帕尔镇。2014年10月21日,自治区政府(新政函[2014]194号)同意将疏附县阿克喀什乡划归喀什市管辖。

CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Archived copy" 中国气象数据网 - WeatherBk Data (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 2018-09-05. Retrieved 2020-04-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- 中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年). China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- "Archived copy" 喀什市历史沿革. XZQH.org. 27 May 2015. Archived from the original on 4 November 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

2013年3月,自治区政府(新政函[2013]35号)同意将疏附县阿瓦提乡划归喀什市管辖。2013年,自治区政府(新政函[2013]207号)批准同意将疏附县英吾斯坦乡划归喀什市管辖(11月20日正式实施)。阿瓦提乡面积87.2平方千米,人口3.42万人;英吾斯坦乡面积109.16平方千米,人口3.98万人。 2014年10月21日,自治区政府(新政函[2014]194号)同意将疏附县阿克喀什乡划归喀什市管辖。阿克喀什乡面积约266平方千米,人口1万余人。至此,全市辖4个街道、2个镇、9个乡:恰萨街道、亚瓦格街道、吾斯塘博依街道、库木代尔瓦扎街道、乃则尔巴格镇、夏马勒巴格镇、多来特巴格乡、浩罕乡、色满乡、荒地乡、帕哈太克里乡、伯什克然木乡、阿瓦提乡、英吾斯坦乡、阿克喀什乡。2015年4月3日,自治区政府批复同意设立西域大道街道(新政函[2015]87号)、东湖街道(新政函[2015]88号)。调整后,全市辖6个街道、2个镇、9个乡。

CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Archived copy" 2019年统计用区划代码和城乡划分代码:喀什市 (in Chinese). National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China. 2019. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

统计用区划代码 名称 653101001000 恰萨街道 653101002000 亚瓦格街道 653101003000 吾斯塘博依街道 653101004000 库木代尔瓦扎街道 653101005000 西域大道街道 653101006000 东湖街道 653101007000 迎宾大道街道 653101008000 西公园街道 653101100000 乃则尔巴格镇 653101101000 夏马勒巴格镇 653101202000 多来特巴格乡 653101203000 浩罕乡 653101204000 色满乡 653101205000 荒地乡 653101206000 帕哈太克里乡 653101207000 伯什克然木乡 653101208000 阿瓦提乡 653101209000 英吾斯坦乡 653101210000 阿克喀什乡

CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 喀什市概况(2017) (in Chinese). Kashgar City People's Government. 12 October 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

喀什市面积1056.8平方千米,人口62.79万(2016年),辖8个街道、2个镇、9个乡。

- Eset Sulaiman, Joshua Lipes (14 September 2015). "Authorities in Xinjiang Require Special Permits to Buy Kitchen Knives". Radio Free Asia. Translated by Eset Sulaiman. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

A Uyghur officer from the Nezerbagh township police station on the outskirts of Kashgar also refused to comment on the notice, but acknowledged that a special regulation is currently in place in the region to control the purchase and sale of tools with blades on them, as well as how the items are used.

CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Shohret Hoshur, Joshua Lipes (9 January 2020). "Uyghurs in Xinjiang Ordered to Replace Traditional Décor With Sinicized Furniture". Radio Free Asia. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

After receiving information about the implementation of the Sanxin Huodong campaign in Kashgar (in Chinese, Kashi) city’s Nezerbagh township, RFA’s Uyghur Service contacted a government employee there who refused to comment on the situation.

CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Ceng Jing (20 January 2020). "Reporter's diary: How Kashgar's first ski park helps drive employment". China Global Television Network. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

Mamat lives in a poverty-stricken village in Nezerbagh Town, some 20 minutes drive from the Kashgar City center.

- Naize’er Bage (Approved - N) at GEOnet Names Server, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- «گۈلنى ۋاسىتە قىلىپ» گۈزەل تۇرمۇش بەرپا قىلىش. Tianshannet (in Uyghur). 28 August 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

قەشقەر شەھىرى نەزەرباغ بازىرىنىڭ

- شامالباغ بازىرىدا ئىنقىلابىي ناخشا ئېيتىش مۇسابىقىسى ئۆتكۈزۈلدى(1). خەلق تورى [people.com.cn Uyghur] (in Uyghur). 15 August 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

قەشقەر شەھىرىنىڭ شامالباغ بازىرى

- قەشقەر شەھىرى نامراتلىقتىن قۇتۇلدۇرۇش ئۆتكىلىگە ھۇجۇم قىلىش جېڭىگە ياخشى ئاساس سالدى. خەلق تورى [people.com.cn Uyghur] (in Uyghur). 23 December 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

قەشقەر شەھىرى سەمەن يېزىسى

- 喀什市2019年涉农资金统筹整合使用实施方案 (in Chinese). Kashgar City People's Government. 27 November 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

建设2703人林果业技术服务队(其中英吾斯塘乡620名、阿瓦提乡464名、伯什克然木乡845名、浩罕乡160名、阿克喀什乡275名、荒地乡40名、帕哈太克里乡199名、色满乡50名、乃则尔巴格镇50名),{...}英吾斯塘乡38台农机设备337万元其中8村玉米收割机2台

- Stanley W. Toops (15 March 2004). "The Demography of Xinjiang". In S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. Routledge. pp. 256–257. ISBN 978-0765613189.

- "KĀSHÍ SHÌ (County-level City)". City Population. Archived from the original on 2017-12-03. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

- 3-7 各地、州、市、县(市)分民族人口数 (in Chinese). Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Bureau of Statistics. 15 March 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Morris Rossabi, ed. (2004). Governing China’s Multiethnic Frontiers (PDF). University of Washington Press. p. 179. ISBN 0-295-98390-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-07. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "Kashgar: Ancient city regains vitality". CCTV.com. 2010-07-07. Archived from the original on 2010-12-26. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- George Michell, in the 2008 book Kashgar: Oasis City on China’s Old Silk Road, quoted by Michael Wines in the New York Times, May 27, 2009. ("To Protect an Ancient City, China Moves to Raze It Archived 2017-12-03 at the Wayback Machine")

- https://reaction.life/orwellian-chinese-government-destroyed-kashgar-fulcrum-silk-road/

- Michael Wines, To Protect an Ancient City, China Moves to Raze It Archived 2017-12-03 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, May 27, 2009

- "Kashgar Sunday Market". Kashgar Guide. Archived from the original on 2013-05-25. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- "Issue 21 – Analysis – Fear and Loathing split Xinjiang's would-be Las Vegas". Archived from the original on 2006-10-03. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- "Kashi, China Page". Falling Rain Genomics, Inc. Archived from the original on 2010-03-09. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- "Kyrgyzstan Daily Digest". Archived from the original on 2009-02-07. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- Railway Gazette International May 2012, p76

- Bus schedule posted in Bishkek’s Western Bus Terminal-correct September 2007

- Everest‐Phillips, Max (1991). "British consuls in Kashgar". Asian Affairs. 22 (1): 20–34. doi:10.1080/03068379108730402.

- "Malacca ties up with sister city Kashgar". New Straits Times. Archived from the original on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

Sources

- Boulger, Demetrius Charles The Life of Yakoob Beg, Athalik Ghazi and Badaulet, Ameer of Kashgar (London: W.H. Allen & Co.) 1878

- Gordon, T. E. 1876. The Roof of the World: Being the Narrative of a Journey over the high plateau of Tibet to the Russian Frontier and the Oxus sources on Pamir. Edinburgh. Edmonston and Douglas. Reprint: Ch’eng Wen Publishing Company. Taipei. 1971.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilüe (魏略) by Yu Huan : A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Archived 2017-12-23 at the Wayback Machine Draft annotated English translation.

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N. 1979. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC − AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. E. J. Brill, Leiden.

- Kim, Hodong Holy war in China. The Muslim Rebellion and State in Chinese Central Asia, 1864–1877 (Stanford University Press) 2004

- Puri, B. N. Buddhism in Central Asia, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited, Delhi, 1987. (2000 reprint).

- Shaw, Robert. 1871. Visits to High Tartary, Yarkand and Kashgar. Reprint with introduction by Peter Hopkirk, Oxford University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-19-583830-0.

- Stein, Aurel M. 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan Archived 2005-02-04 at the Wayback Machine, 2 vols. Clarendon Press. Oxford.

- Stein, Aurel M. 1921. Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China Archived 2005-02-04 at the Wayback Machine, 5 vols. London & Oxford. Clarendon Press. Reprint: Delhi. Motilal Banarsidass. 1980.

- Tamm, Eric Enno. The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China. Vancouver: Doulgas & McIntyre, 2010. See also http://horsethatleaps.com/chapter-6/ Archived 2010-08-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Yu, Taishan. 2004. A History of the Relationships between the Western and Eastern Han, Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties and the Western Regions. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 131 March, 2004. Dept. of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kashgar. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kashgar. |

- Interactive Maps and Slide Shows comparing Old and New Kashgar

- Explore Kashgar's Old Town on Global Heritage Network (GHN)

- Kashgar City government website

- Photos of Kashgar Kashgar Pamir Youth Hostel

- Photos of Kashi dheera.net

- Kashgar berclo.net

- T. Digby, Nests of the Great Game spies Shanghai Star, 9 May 2002.

- Images and travel impressions along the Silk Road – Kashgar

_of_Kashgar%2C_73_CE.jpg)