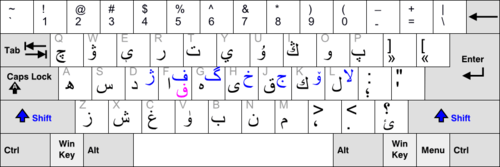

Uyghur Arabic alphabet

The Uyghur Perso-Arabic alphabet (Uyghur: ئۇيغۇر ئەرەب يېزىقى, ULY: Uyghur Ereb Yëziqi or UEY, USY: Уйғур Әрәб Йезиқи ) is an Arabic alphabet used for writing the Uyghur language, primarily by Uyghurs living in China. It is one of several Uyghur alphabets and has been the official alphabet of the Uyghur language since 1982.[1]

| Uyghur alphabet ئۇيغۇر يېزىقى | |

|---|---|

Example of writing in the Uyghur alphabet: Uyghur | |

| Type | Alphabets

|

| Languages | Uyghur |

Parent systems | Proto-Sinaitic

|

Unicode range | U+0600 to U+06FF U+0750 to U+077F |

| Uyghur alphabet |

|---|

| ئا ئە ب پ ت ج چ خ د ر ز ژ س ش غ ف ق ك گ ڭ ل م ن ھ ئو ئۇ ئۆ ئۈ ۋ ئې ئى ي |

|

Extended Perso-Arabic script |

The first Perso-Arabic derived alphabet for Uyghur was developed in the 10th century, when Islam was introduced there. The version used for writing the Chagatai language. It became the regional literary language, now known as the Chagatay alphabet. It was used nearly exclusively up to the early 1920s. Alternative Uyghur scripts then began emerging and collectively largely displaced Chagatai; Kona Yëziq, meaning "old script", now distinguishes it and UEY from the alternatives that are not derived from Arabic. Between 1937 and 1954, the Perso-Arabic alphabet used to write Uyghur was modified by removing redundant letters and adding markings for vowels.[2][3] A Cyrillic alphabet was adopted in the 1950s and a Latin alphabet in 1958.[4] The modern Uyghur Perso-Arabic alphabet was made official in 1978 and reinstituted by the Chinese government in 1983, with modifications for representing Uyghur vowels.[5][6][7][8]

The Arabic alphabet used before the modifications (Kona Yëziq) did not represent Uyghur vowels and according to Robert Barkley Shaw, spelling was irregular and long vowel letters were frequently written for short vowels since most Turki speakers were unsure of the difference between long and short vowels.[9] The pre-modification alphabet used Arabic diacritics (zabar, zer and pesh) to mark short vowels.[10]

Robert Shaw wrote that Turki writers either "inserted or omitted" the letters for the long vowels ا ,و and ي at their own fancy so multiple spellings of the same word could occur and the ة was used to represent a short a by some Turki writers.[11][12][13]

The reformed modern Uyghur Arabic alphabet eliminated letters whose sounds were found only in Arabic and spelled Arabic and Persian loanwords such as Islamic religious words, as they were pronounced in Uyghur and not as they were originally spelled in Arabic or Persian.

| Letter | ا | ب | پ | ت | ج | چ | ح | خ | د | ر | ز | س | ش |

| Latin | a | b | p | t | j | ch | h | kh | d | r | z | s | sh |

| Letter | ع | غ | ف | ق | ك | گ | نگ | ل | م | ن | و | ھ | ى |

| Latin | ain | Gh, Ghain | f | q | k | g | ng | l | m | n | w, o, u | h | y, e, i |

| Letter | ـَ | ـِ | ـُ |

| Name | zabar | zer | pesh |

| Letter | ا | ي | و |

| Name | alif | ye | wáo |

| Letter | ئا،ا | ئە،ە | ب | پ | ت | ج | چ | خ | د | ر | ز | ژ | س | ش | غ | ف |

| IPA | ɑ,a | ɛ,æ | b | p | t | dʒ | tʃ | χ,x | d | r,ɾ | z | ʒ | s | ʃ | ʁ,ɣ | f,ɸ |

| Letter | ق | ك | گ | ڭ | ل | م | ن | ھ | ئو،و | ئۇ،ۇ | ئۆ،ۆ | ئۈ،ۈ | ۋ | ئې،ې | ئى،ى | ي |

| IPA | q | k | g | ŋ | l | m | n | h,ɦ | o,ɔ | u,ʊ | ø | y,ʏ | w,v | e | i,ɨ | j |

Several of these alternatives were influenced by security-policy considerations of the Soviet Union or the People's Republic of China. (Soviet Uyghur areas experienced several non-Arabic alphabets and the former CIS countries, especially Kazakhstan, now use primarily a Cyrillic-based alphabet, called Uyghur Siril Yëziqi.)

A Pinyin-derived Latin-based alphabet (with additional letters borrowed from Cyrillic), then called “New script” or Uyghur Yëngi Yëziq or UYY, was for a time the only officially approved alphabet used for Uyghur in Xinjiang. It had technical shortcomings and met social resistance; Uyghur Ereb Yëziqi (UEY), an expansion of the old Chagatai alphabet based on the Arabic script, is now recognized, along with a newer Latin-based alphabet called Uyghur Latin Yëziqi or ULY, replacing the former Pinyin-derived alphabet; UEY is sometimes intended when the term "Kona Yëziq" is used.[14]

Old alphabet compared to modern

| Old Perso-Arabic alphabet (Kona Yëziq) used before the 20th century | Modern Uyghur Arabic alphabet | Latin | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| بغرا | بۇغرا | bughra | bull camel |

| ارسلان | ئارىسلان | arislan | lion |

| سلطان | سۇلتان | sultan | sultan |

| يوسف | يۈسۈپ | Yüsüp | Yusuf |

| حسن | ھەسەن | Hesen | Hassan |

| خلق | خەلق | xelq | people |

| كافر | كاپىر | kapir | infidel |

| مسلمان | مۇسۇلمان | musulman | Muslim |

| منافق | مۇناپىق | munapiq | hypocrite |

| اسلام | ئىسلام | Islam | Islam |

| دين | دىن | din | religion |

| كاشقر | قەشقەر | Qeshqer | Kashgar |

| ختن | خوتەن | Xoten | Khotan |

| ينگي حصار | يېڭىسار | Yëngisar | Yangi Hissar |

| ساريق قول | سارىقول | Sariqol | Sarikol |

| قيرغيز | قىرغىز | Qirghiz | Kirghiz |

| دولان | دولان | Dolan | Dolan people |

| كوندوز | كۈندۈز | kündüz | day-time |

| ساريغ or ساريق | سېرىق | sériq | yellow |

| مارالباشي | مارالبېشى | Maralbëshi | Maralbexi County |

| لونگي | لۇنگى | Lun'gi | Lungi |

| آلتی شهر | ئالتە شەھەر | Alte sheher | Altishahr |

| آفاق خواجه | ئاپاق خوجا | Apaq Xoja | Afaq Khoja |

| پيچاق | پىچاق | pichaq | knife |

References

- XUAR Government Document No. XH-1982-283

- Zhou, Minglang (2003). Multilingualism in China: The Politics of Writing Reforms for Minority Languages, 1949-2002. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-3-11-017896-8.

- Johanson, Éva Ágnes Csató; Johanson, Lars (1 September 2003). The Turkic Languages. Taylor & Francis. pp. 387–. ISBN 978-0-203-06610-2.

- Benson, Linda; Svanberg, Ingvar (11 March 1998). China's Last Nomads: The History and Culture of China's Kazaks. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 174–. ISBN 978-0-7656-4059-8.

- Dillon, Michael (1999). China's Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects. Psychology Press. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-0-7007-1026-3.

- Starr, S. Frederick (15 March 2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 195–. ISBN 978-0-7656-3192-3.

- Dillon, Michael (23 October 2003). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Far Northwest. Routledge. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-1-134-36096-3.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 236–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- Robert Shaw (1878). A Sketch of the Turki Language: As Spoken in Eastern Turkistan ... pp. 13-.

- Robert Shaw (1878). A Sketch of the Turki Language: As Spoken in Eastern Turkistan ... pp. 15-.

- Shaw 1878

- Shaw 1878

- Shaw 1878

- Duval, Jean Rahman; Janbaz, Waris Abdukerim (2006). "An Introduction to Latin-Script Uyghur" (PDF). Salt Lake City: University of Utah: 1–2. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)