Nicolas Trigault

Nicolas Trigault (1577–1628) was a Jesuit, and a missionary in China. He was also known by his latinised name Nicolaus Trigautius or Trigaultius, and his Chinese name Jin Nige (simplified Chinese: 金尼阁; traditional Chinese: 金尼閣; pinyin: Jīn Nígé).

Life and work

Born in Douai (then part of the County of Flanders in the Spanish Netherlands, now part of France), he became a Jesuit in 1594. Trigault left Europe to do missionary work in Asia around 1610, eventually arriving at Nanjing, China in 1611. He was later brought by the Chinese Catholic Li Zhizao to his hometown of Hangzhou where he worked as one of the first missionaries ever to reach that city and was eventually to die there in 1628.

In late 1612 Trigault was appointed by the China Mission's Superior, Niccolo Longobardi as the China Mission's procurator (recruitment and PR representative) in Europe. He sailed from Macau on February 9, 1613, and arrived in Rome on October 11, 1614, by way of India, the Persian Gulf and Egypt.[1] His tasks involved reporting on the mission's progress to Pope Paul V,[2] successfully negotiating with the Jesuit Order's General Claudio Acquaviva the independence of the China Mission from the Japan Mission, and traveling around Europe to raise money and publicize the work of the Jesuit missions.[1] Peter Paul Rubens did a portrait of Trigault on 17 January 1617, when Trigault was either in Antwerp or Brussels (at right).[3][4]

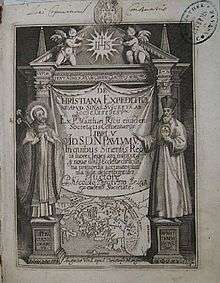

It was during this trip to Europe that Trigault edited and translated (from Italian to Latin) Matteo Ricci's "China Journal", or De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas. (He, in fact, started the work aboard the ship when sailing from Macau to India). The work was published in 1615 in Augsburg; it was later translated into many European languages and widely read.[1] The French translation, which appeared in 1616, was translated from Latin by Trigault's own nephew, David-Floris de Riquebourg-Trigault.[5]

In April 1618, Trigault sailed from Lisbon with over 20 newly recruited Jesuit missionaries, and arrived in Macau in April 1619.[1] [6]

Trigault produced one of the first systems of Chinese Romanisation (based mostly on Ricci's earlier work) in 1626, in his work Xiru Ermu Zi (simplified Chinese: 西儒耳目资; traditional Chinese: 西儒耳目資; pinyin: Xīrú ěrmù zī; lit.: 'Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati').[7][8][9] Trigault wrote his book in Shanxi province.[10]

Aided by a converted Chinese, he also produced the first Chinese version of Aesop's Fables (況義 "Analogy"), published in 1625.

In the 1620s Trigault became involved in a dispute over the correct Chinese terminology for the Christian God and defended the use of the term Shangdi that had been prohibited in 1625 by the Jesuit Superior General Muzio Vitelleschi. André Palmeiro, the Society of Jesus inspector assigned the task of investigating and reporting on the circumstances of Trigault's death in 1628, on information from Trigault's confessor Lazzaro Cattaneo, stated that a mentally unstable Trigault had become deeply depressed after failing to successfully defend the use of the term, and had committed suicide.[11][4]

Publications

- De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas, Nicolas Trigault and Matteo Ricci

- Xiru Ermu Zi (西儒耳目資 "Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati")

.pdf.jpg) Part 1 of 西儒耳目資, "Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati" by Nicolas Trigault

Part 1 of 西儒耳目資, "Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati" by Nicolas Trigault.pdf.jpg) Part 2 of 西儒耳目資, "Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati" by Nicolas Trigault

Part 2 of 西儒耳目資, "Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati" by Nicolas Trigault.pdf.jpg) Part 3 of 西儒耳目資, "Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati" by Nicolas Trigault

Part 3 of 西儒耳目資, "Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati" by Nicolas Trigault

See also

- Jesuit China missions

- Immaculate Conception Cathedral of Hangzhou

- Three Pillars of Chinese Catholicism

- Francisco Varo

References

- Mungello, David E. (1989). Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 46–48. ISBN 0-8248-1219-0..

- Nicolas Trigault (1577-1628 A.D.)

- Peter Paul Rubens: Portrait of Nicolas Trigault in Chinese Costume | Work of Art | Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Logan, Anne-Marie; Brockey, Liam M (2003). "Nicolas Trigault SJ: A Portrait by Peter Paul Rubens" (PDF). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- Histoire de l'expédition chrestienne au royaume de la Chine entreprise par les PP. de la Compagnie de Jésus: comprise en cinq livres esquels est traicté fort exactement et fidelelement des moeurs, loix et coustumes du pays, et des commencemens très-difficiles de l'Eglise naissante en ce royaume (1616) - French translation of De Christiana expeditione by D.F. de Riquebourg-Trigault. Full text available on Google Books. The translator mentions his relation to N. Trigault on p. 4 of the Dedication ("Epistre Dedicatoire")

- Biography in Chinese Archived 2007-07-27 at the Wayback Machine at the National Digital Library of China

- "Xiru ermu zi" (西儒耳目資) bibliographic information and links Archived 2006-09-08 at the Wayback Machine

- "Dicionário Português-Chinês : 葡汉辞典 (Pu-Han cidian): Portuguese-Chinese dictionary", by Michele Ruggieri, Matteo Ricci; edited by John W. Witek. Published 2001, Biblioteca Nacional. ISBN 972-565-298-3. Partial preview available on Google Books. Page 184.

- Heming Yong; Jing Peng (14 August 2008). Chinese Lexicography : A History from 1046 BC to AD 1911: A History from 1046 BC to AD 1911. OUP Oxford. pp. 385–. ISBN 978-0-19-156167-2.

- 何大安 (2002). 第三屆國際漢學會議論文集: 語言組. 南北是非 : 漢語方言的差異與變化 (in Chinese). Volume 7 of 第三屆國際漢學會議論文集: 語言組 Zhong yang yan jiu yuan di san jie guo ji han xue hui yi lun wen ji. Yu yan zu. 中央硏究院語言學硏究所. p. 23. ISBN 957-671-936-4. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

the national capital during the period and the Ricci essays had been written in that city. Later, Lu Zhìwei 陸志韋 (1947) countered with the theory that Trigault's system must represent a Shanxi dialect, because his book had been completed in that province. In response to these claims, Lu asserted that, if Guanhua was indeed a Nankingese-based koine, then the

- Brockey, p. 87.

Further reading

- Liam M. Brockey, Journey to the East: The Jesuit mission to China, 1579-1724, Harvard University Press, 2007.

- C. Dehaisnes, Vie du Père Nicolas Trigault, Tournai, 1861.

- P.M. D’Elia, "Daniele Bartoli e Nicola Trigault", Rivista Storica Italiana, ser. V, III, 1938, pp. 77–92.

- G.H. Dunne, Generation of Giants, Notre Dame (Indiana), 1962, pp. 162–182.

- L. Fezzi, "Osservazioni sul De Christiana Expeditione apud Sinas Suscepta ab Societate Iesu di Nicolas Trigault", Rivista di Storia e Letteratura Religiosa 1999, pp. 541–566.

- T.N. Foss, "Nicholas Trigault, S.J. – Amanuensis or Propagandist? The Rôle of the Editor of Della entrata della Compagnia di Giesù e Christianità nella Cina", in Lo Kuang (ed.), International Symposium on Chinese-Western Cultural Interchange in Commemoration of the 400th Anniversary of the Arrival of Matteo Ricci, S.J. in China. Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China. September 11–16, 1983, II, Taipei, 1983, pp. 1–94.

- J. Gernet, "Della Entrata della Compagnia di Giesù e Cristianità nella Cina de Matteo Ricci (1609) et les remaniements de sa traduction latine (1615)", Académie des Inscriptions & Belles Lettres. Comptes Rendus 2003, pp. 61–84.

- E. Lamalle, "La propagande du P. Nicolas Trigault en faveur des missions de Chine (1616)", Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu IX, 1940, pp. 49–120.

- Liam M. Brockey, “The Death and Disappearance of Nicolas Trigault, S.J.,” The Journal of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, vol. 38 (2003): pp. 161–167.

External links

- Bibliographical information of Xiru Ermu Zi at the Ricci 21st Century Roundtable database, supported only by 5.0 or later versions of Internet Explorer

- Facsimile of Xiru Ermu Zi at Gallica